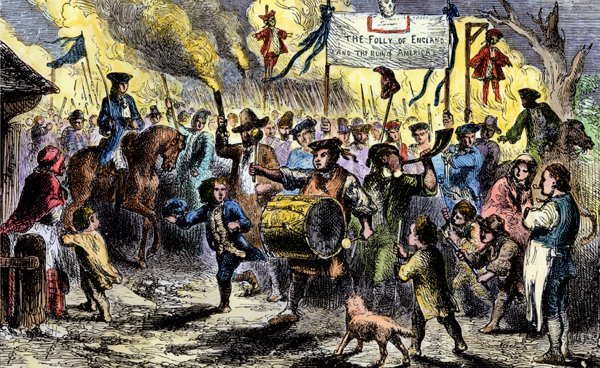

Patriots protested the Stamp Act by demonstrating and hanging effigies.

It was August 14, 1765. Across Boston several thousand angry people poured out into the streets. Shouts of “Liberty, property, and no stamps!” filled the air. The marchers were furious about the Stamp Act, a new law that taxed paper goods and documents of all kinds. That night enraged protesters burned a straw effigy of Andrew Oliver, the unlucky local official picked to collect the taxes. The mob also tore down a building Oliver owned and then headed to his home and wrecked furniture there. More destruction followed in the days to come.

The Stamp Act of 1765 was part of a new policy for the 13 American colonies—one that drove many colonists to protest British rule. Leading the fight against the policy were American colonists known as Patriots. They challenged British efforts to raise taxes and squash the colonists’ freedoms. The Patriots’ ideas and actions put the colonies and Great Britain on the road to war.

A CHANGING RELATIONSHIP

Until the 1760s Parliament and the British crown paid little attention to the distant American colonies—and most Americans liked it that way. When Parliament did pass laws that affected the colonies, the colonists sometimes ignored them. For example, they often smuggled goods they wanted from other nations instead of buying them from Britain. Colonists also elected local officials with a large degree of independence from London.

The Boston protests were led by a group of Massachusetts merchants and craftsmen called the Sons of Liberty. The group formed in Boston during the summer of 1765 and met in secret at first. Soon they numbered 2,000 men, and their protests drew much attention to the Patriot cause. By the end of 1765, Sons of Liberty groups existed in every colony.

But the relationship between the colonies and Great Britain grew tense after 1763. That year the British won the French and Indian War, in which Great Britain battled France for control of North America. Britain’s victory gave it control of Canada and the eastern half of what became the United States. The war had been costly, and British officials demanded that colonists help pay for the future defense of the colonies.

In 1764 Parliament passed the American Revenue Act, known as the Sugar Act, which taxed goods including sugar, wine, coffee, and some types of cloth. The Sugar Act was the first law to raise new money in the colonies. Many merchants believed the new taxes would hurt their businesses.

The Americans cherished the British tradition that gave people the right to approve the taxes they paid. They did this through the representatives they elected to Parliament or colonial legislatures. The colonies, however, had no voting representatives in Parliament. More Americans began to protest against “taxation without representation.”

In 1766 Parliament repealed the Stamp Act. But new taxes soon followed. The first of what came to be known as the Townshend Acts taxed glass, paint, paper, and tea imported from Britain. Some colonial merchants protested with a boycott of British goods. Boston was the center of the anger against the new laws. British officials there clamped down on smuggling. On June 10, 1768, the crew of a British warship seized a ship owned by Patriot merchant John Hancock, who was known for smuggling tea and molasses into the city. A crowd gathered to protest. Fists flew as the Americans beat up the British officials, leaving one of them bloody.

The violence in Boston led King George III to send British troops there. Soon they were camped in the heart of Boston. The residents shouted insults at the soldiers, known as “Redcoats” and “lobster backs” because of their bright red uniforms.

A MASSACRE IN BOSTON

At times citizens and soldiers fought. The worst violence came March 5, 1770. In front of the Custom House, British guard Private Hugh White was arguing with colonist Edward Garrick. Soon a crowd of angry colonists gathered in support of Garrick, hurling taunts of, “bloody lobster back” and “lousy rascal.”

The Americans didn’t just toss insults at the guard on duty that cold March night. The growing crowd pelted the soldier with chunks of ice. More soldiers rushed to the scene, and the crowd threw snowballs and sticks at them. Someone shouted, “Fire!” and the soldiers fired their guns into the shouting mob. Three men fell dead to the ground. Two of the eight others who were wounded died later in what the Patriots called the Boston Massacre. Eight British soldiers and a captain were arrested and later tried on murder charges. All but two were acquitted.

The killings enraged some Boston Patriots, but the violence did not continue. Still, the residents’ hatred of the troops simmered. It wouldn’t be long before it reached a boiling point.

A RIOT OVER TEA

Most colonists drank tea every day. By 1770 Parliament had abolished all of the Townshend Acts but one—the tax on tea. In May 1773, though, Parliament passed the Tea Act. The law lowered the tax on tea, but allowed only the British East India Company to sell tea in the colonies. Even though colonists would pay less for the East India tea than for smuggled tea, they viewed the Tea Act as just one more example of British attempts to control their lives.

Several thousand people jammed into Boston’s Old South Meeting House December 16, 1773, to discuss the fate of three loads of tea sitting in the harbor. The Patriots did not want the tea to come ashore. When it became clear the governor wouldn’t let the ships leave until the tea was unloaded, Patriot leader Samuel Adams stood. “This meeting can do nothing more to save this country!”1 he shouted.

Adams’ words were a signal to other Patriots in the crowd. That night dozens of men, some disguised as American Indians, boarded the ships and threw all the tea into the harbor.

In London an angry King George quickly responded to this “Boston Tea Party.” He had Parliament pass several laws that punished Boston and the Massachusetts colony as a whole. They included shutting down the port of Boston and limiting local control of the government. Americans called these laws the Intolerable Acts.

Lawmakers called for a meeting to discuss how the colonies could act together to protest the new laws. Every colony except Georgia sent delegates to a meeting held in Philadelphia. This First Continental Congress called for another boycott of British goods if the laws punishing Massachusetts were not repealed.

King George III and his advisers ignored the colonists’ demands. In the colonies some members of Congress feared war might break out. But few colonists talked about independence from Great Britain. Most just wanted to protect the rights and freedoms they had always enjoyed as British citizens.

In Massachusetts, though, militia troops prepared for war. Their actions made royal governor Thomas Gage nervous. In September 1774 Gage ordered his troops to seize a large amount of gunpowder used by the militia. The incident sparked the militia to train men to serve as Minutemen—soldiers who were capable of fighting at a minute’s notice.

Early in 1775 Gage received orders to arrest the Patriot leaders in Massachusetts. He also made plans to capture more of the local militias’ weapons and supplies.

Gage put his plan into action the night of April 18. He sent troops to Concord, a town northwest of Boston. On horseback, Paul Revere and two other Patriots dashed ahead of the Redcoats to warn colonists along the way.

The next morning Minutemen in Lexington led by Captain John Parker waited for the advancing Redcoats. Parker had already decided that his men would not fire on the British unless the British fired first. When Redcoats came within sight, Parker told his men to back down. Some obeyed him. Others, like his cousin Jonas Parker, did not budge.

Three British officers approached the Minutemen. One officer demanded, “Ye villains, ye rebels, disperse! Damn you, disperse!”2

The scene quickly became chaotic. A gun fired, though no one knows who pulled the trigger. More gunfire quickly followed. Jonas Parker fell to the ground, hit by a British lead ball. He struggled to load his gun and fire back, but a British soldier stabbed him with a bayonet. Seven other Americans also died that morning.

The British then continued to Concord. The worst fighting of the day broke out in Concord and along the road back to Boston during the British retreat. Hiding in houses and behind fences, the Americans took deadly aim. They paid back the Redcoats for the deaths in Lexington, killing or wounding about 250 British troops. With the fighting that day, the Revolutionary War had begun.