Chapter Two

The Dyle

11–16 May 1940

‘In a stricken panic [the villagers] were obliged to leave their homes immediately. The old, the sick, women, children and babies just fled in terror. It was as if an avalanche had hit them.’

Lieutenant Michael Farr, 2/DLI at La Tombe,

14 May 1940.

Early on the morning of 10 May Lieutenant Anthony Rhodes, serving with Headquarters, 3rd Divisional Engineers, was woken when his bedroom door burst open. Standing in front of him was Mademoiselle Wecquier, the daughter of the house in which he was billeted. ‘Lieutenant’, she said, ‘we have been invaded.’ Rhodes confessed to be more absorbed by the fact the young lady in question was only wearing a silk nightdress and was ‘charmingly silhouetted against the rays of the sun’, it wasn’t until a few moments later that he realized that the real war had begun and ‘all hell was about to be let loose’.1 Two hundred miles to the west Lieutenant Anthony Irwin of 2/Essex was just passing the Isle of Wight bound for Southampton on ten days leave when – much to the irritation of all those on board – the ship was turned around and returned to Boulogne where ‘our presence confused the issue. No one knew what to do with us and no one much cared.’ But as he candidly declared later, ‘Thank God, we didn’t know how much was to happen in the next ten days.’2

Operation David, the code word transmitted to every British Army unit on the Franco-Belgian border, signalled the end of the Phoney War and the move east to the River Dyle. The main fighting force was headed by motorcycle units of the 4/ Royal Northumberland Fusiliers (4/RNF) and the Morris CS9 Armoured Cars of the 12th Lancers which were described in the Regimental History as ‘under-engined, under-armed and under-armoured; being in fact the latest thing of its kind, already obsolescent’.3 The 12/Lancers were commanded by 43-year-old Lieutenant Colonel Herbert Lumsden, a regular officer who had served with E Battery Royal Horse Artillery in the First World War, winning the MC in July 1918. Transferring to the 12/Lancers in June 1925, he had been in command of the regiment since 1938. When the move to the Dyle was confirmed Lumsden – like many of his colleagues – was still on leave in London but on hearing ‘the balloon had gone up’ was back in command by midnight on 10 May – six hours after the Lancers had taken up their positions on the Dyle! Considerably quicker than Anthony Irwin who took several days to find his unit.

The British move to the Dyle was carried out with little interference from the Germans and apart from the final few miles, the forward battalions were transported by the troop-carrying companies of the Royal Army Service Corps (RASC). There may not have been much enemy air activity in the darkness but navigating across 75 miles of Belgium proved for some to be more demanding than first thought. 21-year-old Hugh Taylor of the 1/Suffolks had two lorries allocated to his platoon and before long found himself in the driving seat with the RASC driver sound asleep next to him. Driving with only side lights and diligently following the axle light of the vehicle in front of him he rattled on ‘through village and lanes, over bridges and through woods’ by which time, he tells us, he had lost all sense of direction:

‘After about four hours we entered a town and the light in front disappeared over a bridge, when I reached the crest of the rise I found to my horror that the tail light in front had gone and there was a cross road in front. I hastily looked for a guide, which the Provost Corps had put out when we deviate from the straight run, but saw none ...I had not gone far before I realised that I was wrong, the road gave a twist to the right and I knew that I had gone in the wrong direction. I woke the driver up and told him to let me see the map as we were lost.’4

Having turned around and knocked down a gate post in the process Taylor and his two lorries eventually came to a road junction where, to his relief, stood a Red Cap of the Provost Corps who directed him to a small convoy of vehicles directly ahead:

‘They had stopped, so I pulled up behind them and found my Company Commander was just coming along to find out if anyone was lost. He found me on the tail of the convoy and directed me further up the road, where I found my own company and discovered to my delight that I had never been missed.’5

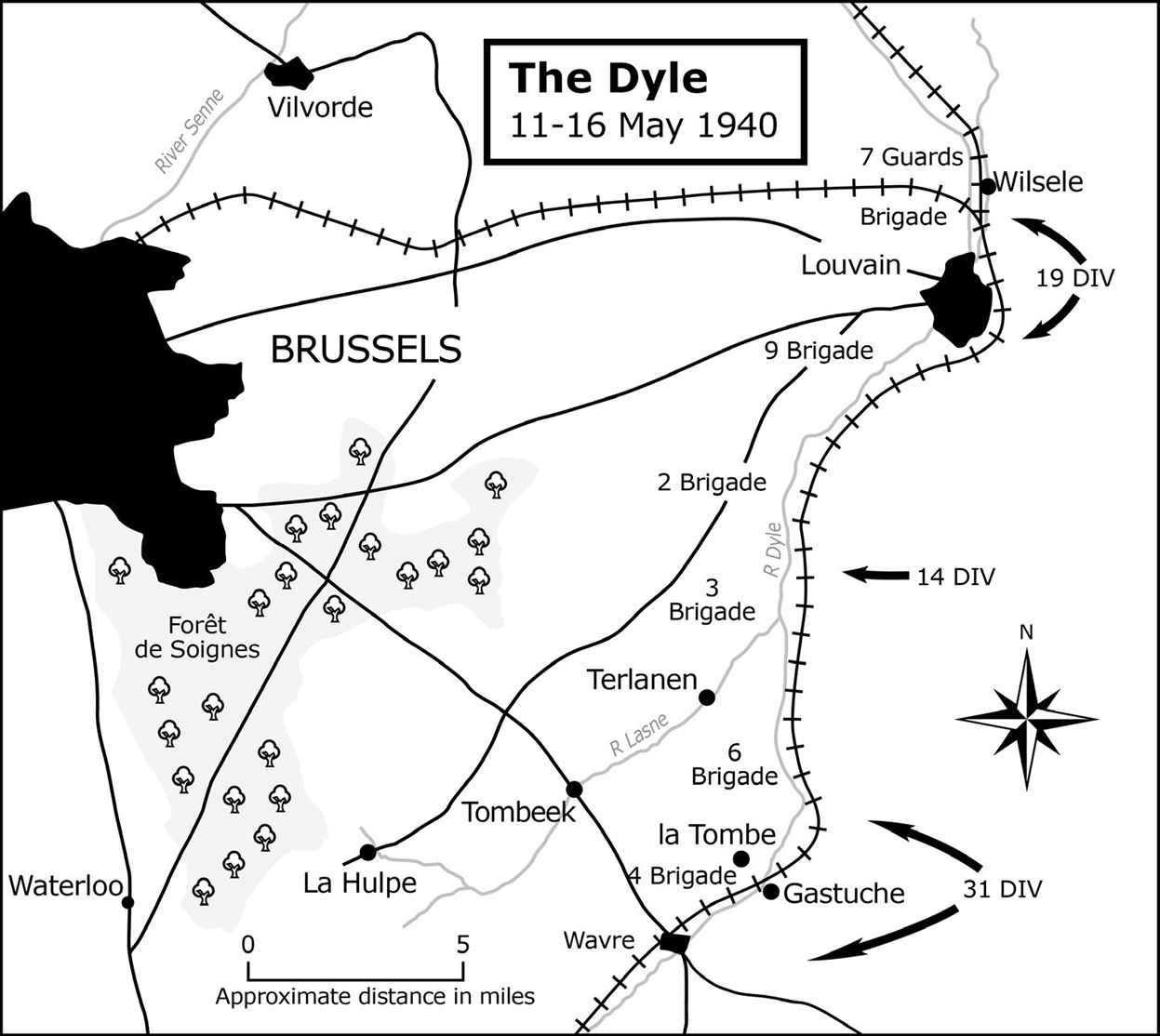

Gort’s plan was to place the 1st and 2nd Divisions on the right flank and the 3rd Division on the left astride Louvain. By way of reserve the 48th Division was ordered to move east of Brussels and the 4th and 50th Divisions to the south. In addition the 44th Division was under orders to march to the Escaut south of Oudenaarde and the 42nd Division placed on readiness to take up station to their right if needed. After the initial move by motor transport, the leading infantry brigades completed the final approach on foot; for many of these men Saturday 11 May brought them into contact with the stream of refugees heading west ahead of the invading Germans. 20-year-old Private Ben Duncan, marching with the 2nd Battalion Hampshire Regiment (2/Hampshires) was horrified at the targeting of defenceless civilians by the Luftwaffe. ‘One broke away and as he stumbled in our direction we could see that in his arms he carried a small body which we saw as he reached us that it was a little girl of some five or six years of age.’6 The child was dead and there was little if anything Duncan and his mates could do as they marched on against the seemingly endless tide of humanity. But what was perhaps a little more worrying was the sight of Belgian Army units apparently in retreat. Hugh Taylor and the Suffolks noted they had ‘very antiquated equipment and were struggling along the road on either side in all types of uniform, some armed, others not.’

The plight of refugees and indifferent Belgian soldiers was something that quickly became apparent to the 12/Lancers as they crossed the Dyle towards Diest. Tasked with linking up with the French Cavalry Corps in the Tirlemont area and reporting on the state of the Belgian defences on the River Ghette, they found no sign of the Belgians and were faced with a 4-mile gap between the French 3rd Light Mechanized Division (3/DLM) and units of the Belgian 1st Cavalry Division. Lumsden had little choice but to fill the gap himself, realising that ‘the plans of the French 3/DLM and the Belgian units on the Ghette did not completely dovetail.’ This was Lumsden’s first indication that all was not well with the Belgian defence further east, a sentiment that was confirmed early on 12 May when German tanks were seen on the Tirlemont road.

Plan D had been based on the assumption that the Germans would, at the very least, take a week to force the Belgian border fortifications which ran along the Albert Canal and the Meuse. The Belgian defences were supported by strong positions on the near bank and all the bridging points had been prepared for demolition. The speed and audacity of the German attack was a major disaster for the Belgians who failed to demolish all the Meuse bridges and lost the Eben-Emael fortress to an airborne glider assault. It was the two Meuse bridges at Vroenhoven and Veldwezelt that the British Advanced Air Striking Force attacked on 12 May with Fairy Battles from 12 Squadron, a sortie which resulted in some damage to the bridges far outweighed by the loss of all five aircraft. Two posthumous VCs, awarded to Flying Officer Donald Garland and Sergeant Thomas Gray, testified to the ferocity of the encounter.

As the Belgians fell back onto the line of the River Ghette, Lumsden’s men had some difficulty in getting the Belgian sappers to demolish the Ghette bridges. Lieutenant David Smith and his section of 101/Field Company Sappers who had been attached to the 12/Lancers, were now ordered up to the Ghette to ensure the bridges were ready for demolition. Smith found the Belgian attitude to blowing the bridges quite alarming. ‘From the very outset of the campaign it was difficult to get the Belgian sappers to fire demolitions and quite often they seemed to have no settled plan for belts of demolitions.’ His frustration was apparent in his 13 May diary entry when he wrote that despite successfully blowing the bridges along the Ghette, the Belgians retired from a position that could have been held successfully for much longer leaving the demolished bridging points ‘uncovered by fire, thus leaving the enemy to employ with impunity whatever devices he wished to overcome the obstacle created’.

The 12/Lancers were by now engaged with the German 19th Division along the Ghette. A Squadron was involved in a sharp fire fight with a German motorcycle patrol from IR 17 and a fifteen-strong German mounted patrol which had swum the river was wiped out by Second Lieutenant Edward Miller-Mundy and 3 Troop. Despite losing three armoured cars from bombing and shellfire Lumsden was becoming increasingly concerned that the Belgians had no real intention of fighting for and holding the line of the Ghette; a suspicion already raised by David Smith. ‘It was interesting,’ wrote Lumsden, ‘the number of anti-tank guns, in fact guns of all sorts, which were constantly on the move, when one would have expected them to be in position and dug in.’7 At 1.00am on 14 May the Lancers began their withdrawal and by the afternoon were back across the Dyle and in reserve at Orphen. The infantry battle along the Dyle was about to begin.

Hot on the heels of the 12/Lancers were the 3rd Division engineers who arrived at Eveberg around midnight on 10/11 May. Captain Dick Walker, the 3rd Division RE Adjutant, immediately left with the Chief Engineer Officer (CRE) Lieutenant Colonel Desmond Harrison, for Louvain. ‘We drove through the town which was quite empty except for a few Belgian police, and had a look at the canal and bridges.’ Intent on allocating the RE field companies to their areas of operation the two officers rapidly came to the conclusion that building any tank obstacles in the centre of Louvain was out of the question and the railway line to the east of the city would have to be the basis of any defence mounted by the infantry:

‘Looking at the canal to the north of Louvain and the branches of the canal in Louvain itself the decision to use the railway as the main obstacle was strongly confirmed. The canal had three branches in Louvain and these were on average only 20 feet wide and the river was low ... no bridges had been prepared and very little defensive work had been done. I only saw one pillbox, there were, however some de Cointet obstacles, wire and rail obstacles.’8

It was a view shared by Major General Bernard Montgomery when he arrived in Louvain. Initially frustrated in their attempt to garrison Louvain and its environs by the refusal of the Belgian 10th Division to hand over responsibility – an agreement that had been decided upon several weeks previously – British units waited rather impatiently in the wooded area of the Eikenbos to the west of the city. Montgomery, in a rare flash of tact, informed the Belgians that he was placing his 3rd Division under their command and would accordingly reinforce their line. ‘I decided that the best way of getting the Belgians out and my division in was to use a little flattery.’ His ruse appeared to work as the Belgians withdrew on 12 May ‘when the Germans came within artillery range and the shelling began’.9

The medieval city of Louvain had already suffered badly at the hands of the Germans in 1914 and was about to bear the brunt of the German attack again. It came as no surprise to the 2/Royal Ulster Rifles (2/RUR) and the 2/Lincolnshire Regiment (2/Lincolnshire) as they advanced through the already badly damaged city to find the vast majority of the 32,000 inhabitants had already begun the move west, leaving them as the principle custodians of a rapidly emptying metropolis. Moving quickly to the eastern edge of the city the Ulster Rifles were allotted a front of some 2000 yards running from the communal cemetery on their right to a point just north of the bridge over the Diest-Louvain road. The Lincolnshires were on their right with D Company occupying the communal cemetery and the remaining companies deployed along the railway to a point west of the N251. To the north of the Ulster Rifles were 7 Guards Brigade deployed in what the Grenadiers’ regimental historian described as an uncomfortable position forward of the Dyle Canal. ‘The Germans had bombed the marshalling yards, the wreckage of engines and rolling stick was piled so high that many of the pill boxes had a view of no more than twenty yards and were therefore isolated one from the other.’10

The line of the railway occupied by the Ulster Rifles was another which was far from perfect. A wide boulevard, which was the continuation of that which encircled Louvain, ran along the southern edge of the city and along most of the western edge of the railway line. The railway line ran through a wide cutting in the south and along an embankment to the north. This inevitably made the positioning of section posts difficult as fields of fire nowhere exceeded 50 yards and those in the railway station were often considerably less. On the extreme left of the battalion – north of the station and close to the signal box – one A Company platoon post was perched on top of the railway embankment and only accessed via a ladder. Dubbed the Bala-Tiger post, it was named after the two subalterns who commanded it, Lieutenants Humphrey ‘Bala’ Bredin and William ‘Tiger’ Tighe-Wood. Bredin had already won the MC and bar in April 1938 while the battalion had been serving in Palestine and, despite being overlooked by a tall building some 20 yards away, was in no mood to allow his position to be overrun. Bredin’s nickname ‘Bala’ is thought to have originated from the name of a fort in Peshawar and it was with some coincidence that on being posted to Palestine he found himself quartered in an Arab village named Bala.

The railway station, under the command of 22-year-old Lieutenant Pat Garstin, was situated at the eastern end of the wide Avenue des Allies. Garstin’s men held the entrance hall and Platform 2 together with its subways and between them and Platform 1 was a thick belt of barbed wire which had been attached to the wooden sleepers, preventing movement across the rails. It was this unlikely battleground that prompted the Daily Express to use the headline ‘The Battle Now Raging on Platform One’ in a later report of the fighting. Commanding the Ulstermen was 42-year-old Lieutenant Colonel Fergus ‘Ghandi’ Knox who had served as a second lieutenant with the battalion in the First World War. His command of the Ulster Rifles in 1940 was perhaps his finest hour and at Louvain, having adopted a motorcycle driven by Sergeant Norman Victor as his principle mode of transport, he directed the battle from the pillion seat earning a well deserved DSO in the process.

By dusk on 14 May the battalion was in contact with the enemy all along the railway line and for the majority it was their first real introduction to the German MG 34 machine gun – or ‘Spandau’ as it became known somewhat inaccurately – which succeeded in jangling the nerves of many of the less battle hardened of the Irish. The battalion historian remarked that ‘after dark there was a tendency [for the forward posts] to continue firing rifles and Brens whether or not a target was visible.’11 Nevertheless, it was just as well they were alert as in the closing hours of 14 May there were several attempts made by the Germans to penetrate the line, a situation that prompted Knox to move C Company and 29-year-old Captain Albert Ward into Louvain to counter any threat, a threat he took seriously enough the next morning to bring B Company and Captain Arthur Davis into the city as additional support.

A two hour German artillery barrage opened the fighting at dawn on 15 May countered by two batteries of 76/Field Regiment with the 7/Field Regiment’s batteries of 25-pounders firing around 700 rounds in response. Undeterred, German infantry focussed their attack on the railway station and succeeded in penetrating the station yard. The problems around the station were exacerbated not only by the close proximity of the two platforms but also by the embankment and the buildings which overlooked the whole complex. To make matters worse German infantry had also taken up positions amongst the tangle of ruined railway rolling stock from where they directed a vicious curtain of machine gun fire.

Adding to these difficulties enemy infantry had also begun to infiltrate between the Bala-Tiger Post and the Guards’ positions to their north and at one point got behind the station, cutting off many of A Company by firing down the Avenue des Allies into the station. The Irish reply was an instant counter-attack with grenades and Bren gun fire which – the war diary tells us – restored the status quo and resulted in a ‘considerable reduction in fire’. So successful were these counter attacks that the German 19th Division was reinforced with units from IX Korps and the XVI Panzer Korps. Undeterred by the precarious nature of their position, Garstin’s men used the subways to their advantage as the weight of German fire shattered the platform canopies above, showering them with shards of glass. Every so often the energetic Garstin would dart up from a subway, fire a burst from his Bren and vanish, only to reappear elsewhere to repeat the exercise, giving the impression the station was held by a much larger force.

At the Bala-Tiger post the defending garrison, despite their exposed position on the top of the embankment, had already inflicted a number of casualties on the attacking infantry. Overlooked by German snipers, the post – like the railway station – was continually under fire but even when surrounded, Lieutenant Bredin – who was usually armed with a rifle and his trademark blackthorn stick – refused to give way. Much to the chagrin of the Germans the narrow trench which nestled amongst the cinders and slag of the embankment remained firmly in Irish hands until the order was given to withdraw from Louvain.

Further north at Wilsele the initial enemy contact with the 1st Battalion the Coldstream Guards (1/Coldstream) on 14 May was easily brushed aside but as the attack gathered strength the outpost positions east of the canal were ordered to withdraw. No.2 Company posts were brought in without much difficulty but the No. 3 Company outposts had been penetrated resulting in Captain Richard Gooch and 24-year-old Lieutenant Richard Crichton together with Guardsman Lawrence Cook crossing the canal: ‘By attacking with grenades they managed to get the forward sections out and back across the canal; but a number of men had to swim across – no easy matter in the dark – and two were drowned.’12 Crichton was severely wounded in the action and almost lost an arm. Gooch and Crichton were both awarded the MC and Guardsman Cook the MM.

The next morning – 15 May – German infantry, reinforced by units from IX Korps, had moved machine guns and snipers into the houses on the east bank of the canal and attempted to cross it on No. 3 Company’s frontage. Frustrated in this attempt by the Guards mortar platoon, orders were then received for No. 2 Company to retire in line with the 1st Battalion the Grenadier Guards (1/GG) which had reportedly pulled back in the face of a heavy artillery barrage. During the course of this retirement Captain Lord Frederick Cambridge was killed, but, as the regimental historian points out, the information was incorrect and it was only the outposts that the Grenadiers had withdrawn from:

‘Since it was considered essential that the canal should still be held, the battalion was ordered to recapture the position from which 2 Company had withdrawn. The carriers under Lt. Tollemache, and the commanding officer [Lieutenant Colonel Arnold Cazenove] in a cavalry tank, went up to see how things were by the canal, and found not many of the enemy had yet got across. None the less, a heavy attack was laid on with the help of the tanks of the 5/Inniskilling Dragoons under the cover of which 1 Company (Maj Campbell) counter-attacked and succeeded in re-establishing themselves on the canal without losing any men.’13

One further action of note on the 15th was that of Lance Corporal Percy Meredith who successfully dealt with a sniper who was giving the Coldstream posts some anxious moments. Crossing the open ground between his position and the buildings on the west bank of the canal, Meredith entered the building and silenced the sniper. His award of the Distinguished Conduct Medal (DCM) was presented to him by Montgomery at Roubaix on 26 May along with Gooch and Cook. Other recipients of gallantry awards that day were Fergus Knox who was awarded the DSO and Pat Garstin the MC.

Although British forces all along the length of the Dyle were engaged by the Germans, it appeared that the enemy’s main attacks were concentrated on both flanks. Thirteen miles further south on Major General Henry ‘Budget’ Loyd’s 2nd Division front, the sector ran from the left of Blanchard’s French First Army, north along the Dyle through Wavre, before it linked up with Major General George Alexander’s 1st Division. The 49-year-old Loyd was a former Coldstream Guardsman who had concluded the previous war as a decorated battalion commander. His three brigades – largely composed of regular troops – would see some of the bitterest fighting of the campaign. Sadly Loyd collapsed on 16 May and was replaced by Brigadier Noel Irwin, commanding 6 Brigade, who took command four days later – but not before the fighting around Gastuche had put the Durham Light Infantry on the front pages of the national newspapers with the award of the first VC of the ground war.

The three battalions of 6 Brigade began arriving on the Dyle in the early hours of 11 May and one of the first to arrive at La Tombe was Lieutenant Michael Farr serving with the 2/DLI. His diary betrays his evident dismay at the plight of the refugees who were flooding across the Dyle in great numbers. ‘They were’, he wrote, ‘in a pitiable state, baggage, old carts, prams. Worst of all they did not know where they were going.’14 Farr was a former Charterhouse schoolboy and recognising there would be no place for him in the family wine firm, decided on a career as a regular soldier, joining the battalion in 1938 from Sandhurst and at 21-years-old was now the battalion signals officer.

Looking across the river from their new positions the Durhams were without doubt uncomfortable with their deployment. The narrow river valley of the Dyle ran along the entire 2,000 yard frontage with the Louvain – Wavre railway line to the east crossing the river a little to the west of Gastuche. Beyond the river were several hundred yards of flat ground which eventually gave rise to thickly wooded steeper ground. With battalion headquarters at La Tombe, C Company was deployed to an outpost line on the high ground east of the river at Les Monts and Les Pres while the remaining three companies took up their positions along the line of the river. Townsend’s diary detailed the deployment of the remaining companies:

‘A Company on the right had two platoons forward on the railway embankment with one platoon in reserve in the woods ... B Company in the centre also had two platoons forward, one on the railway and 10 Platoon on a broken tongue of ground where the river made a loop on the east and then ran away from the woods. This platoon position was even more overlooked than the other by the high ground of Gastuche immediately on the east side of the river. B Company HQ was in the old château with the reserve platoon. The right platoon of D Company had a blockhouse in its area and also covered the road and bridge. The left Platoon of D Company connected with the right company of The Royal Berkshires.’15

Their positions were not improved by the poor fields of fire which, in many places, was restricted by the trees and undergrowth making observation from behind the forward positions difficult. Dividing B and D Companies was a minor road – Drève de Laurensart – which crossed the railway line and the river over a narrow wooden bridge, described by Sergeant Martin McLane as ‘about fifty yards long, eight yards wide and with ornamental balustrades on either side’. It was this bridge that was to become the focus of attention on 15 May.

The first contact with the German 31st Division came on 14 May on the east bank of the river at the roadblock manned by C Company on the N268. Although Captain Blackett’s forward section soon dispersed the approaching armoured vehicles, the remaining German advance guard were able to maintain their observation of the Durhams from the safety of Gastuche from where they directed a hail of machine gun fire onto the forward positions. Private Dusty Miller and his mate George Blackburn from 16 Platoon were in foxholes on either side of the road when C Company withdrew across the wooden bridge. With news of their skirmish with the enemy ringing in his ears Miller was more concerned with making sure he and George Blackburn were not caught up in the blast when the bridge went up. A warning shout from behind was enough to send the two men scurrying back for cover. ‘I went hell pelting out and we had just got into position when up went the bridge.’16

The 15 May opened with clear skies and a heavy mortar bombardment on the D Company positions at 6.00am during which the company commander, Captain Bill Hutton, was badly wounded. The bombardment quickly enveloped B Company and 10 Platoon, commanded by 24-year-old Second Lieutenant John Hyde-Thompson, came under a sustained attack as did the blockhouse in the nearby D Company sector. Garrisoned by Corporal Matthew Wilson and his section, their resistance collapsed when they ran out of ammunition and, unable to reach them through the heavy German machine-gun fire, the Durhams could only watch as the majority of Wilson’s section were cut down attempting to escape. Only two men survived, one of which was Private Leslie Robinson who returned to the blockhouse under fire to retrieve the Bren gun which had been left behind. Originally recommended for the MM, Robinson’s bravery was eventually downgraded to a mention in despatches.17

A counter-attack by 18 Platoon failed to recover the blockhouse but did manage to close the gap left by Corporal Wilson’s section. In the meantime Hyde-Thompson’s men were rushed from the cover of the paper mill, the enemy using a small weir to cross the river. Michael Farr’s diary recorded the fight that followed:

‘The bravery of Lt. John Hyde-Thompson was something never to be forgotten. With all his men killed the German officer called him to surrender. John’s reply was to pull out his revolver and shoot him dead. He then fought off the attacking Germans singlehanded using grenades. Retreating quickly to another platoon [12 Platoon] on his left he attempted a sudden counter-attack which failed ... His great courage thus checking the advance.’18

Hyde-Thompson had in fact held on until 9.00am before he was overrun, earning a MC in the process. He was eventually taken prisoner but his repeated counter-attacks had stalled the German advance long enough for Lieutenant Colonel Robert Simpson to bring up C Company from reserve. Simpson had only been in command since March after Victor Yate had been sent home sick, but as the events of the next thirteen days would prove, he was the ideal replacement.

The situation was now in the balance. German infantry were across the river in front of D Company and were up to the railway embankment on B Company’s front. Without immediate action by the Durhams the breach in the line created by this incursion would be exploited and their positions compromised. The Durhams’ only possible reply was the counter-attack carried out by C Company at 11.00am; its partial success was observed by Townsend:

‘[Platoon Sergeant Major (PSM)] Ditchburn’s platoon on the left had little cover and were almost wiped out by fire from the embankment. They did not succeed in reaching the railway. PSM Pinkey on the right had more cover and succeeded in reaching the railway from whence with 12 Platoon they forced the enemy back by enfilade fire. At this time heavy mortar fire was searching all cover around B Company and more enemy machine guns were firing from the high ground opposite. Captain [Frank] Tubbs was hit and evacuated, Lieutenant [John] Bonham taking over command.’19

Although George Pinkey was later taken prisoner, he would have had some consolation that his award of the DCM was one of the first to be awarded in the campaign. But there is no doubt it had been a costly attack and according to the war diary both C and B Company lost heavily in the face of intense enemy machine-gun fire leaving the dead strewn across the battlefield. C Company’s attack had restored the status quo to an extent and despite enemy gains making life difficult for the forward positions, the fire from 11 Platoon from the moated château and the arrival of Captain Anthony Lewis with his company of 1/Royal Welch Fusiliers put paid to any further enemy intentions for the time being.

Townsend’s diary also records the action that was taking place on the D Company front, noting that the enemy were attempting to cross the river on the site of the demolished wooden bridge on the left flank. In position immediately in front of the bridge was 16 Platoon, commanded by 26-year-old Second Lieutenant Richard ‘Dick’ Annand. The Annand family were no strangers to the high personal cost of war. Annand’s father, Lieutenant Commander Wallace Annand, had been killed in June 1915 serving with the Collingwood Battalion during the Gallipoli campaign and had Dora Annand known the circumstances in which her only son and his platoon now found themselves, she might well have thrown her hands up in horror.

Before it had been destroyed the wooden bridge had carried the narrow Drève de Laurensart over the river, which flowed at this point between steep muddy banks. German efforts to capture the bridge had so far been prevented by Dick Annand and his platoon, but just before dusk German engineers managed to establish a bridging party in the river bed. It was the beginning of a furious engagement that was recorded in Michael Farr’s diary:

‘The enemy came in great force and might. They ran into the withering fire of Dick’s men; into an inferno of bullets; the enemy rolling down like ninepins. The dead and the dying met the same fate, on and on they came, heaps of dead and screaming men. The Hun had become wild and bewildered and could not shake Dick Annand and his men who were fighting with almost unreal guts. On they came again, clambering onto the parapets of the bridge and sliding down the banks.’20

Amongst the defending Durhams was Sergeant Major Norman Metcalf who felt that although ‘there must have been thousands of them’ the enemy had been ‘bumped off like ninepins in bundles of ten’. But despite Metcalf’s rather encouraging view of the battle the heavy casualties appeared not to deter the enemy’s ambitions regarding the bridge. After a short period of calm the crash of a heavy mortar barrage heralded another German attack, this time it was almost dark when Germans made their next attempt to cross the river.

Dusty Miller recalled German tracer lighting up the approach to the bridge and thought ‘the approaching German army looked like a moving field of steel with the lights reflecting off their helmets.’ Farr’s diary – a little less colourful than Metcalf’s account – acknowledges the extraordinary bravery demonstrated by Dick Annand as he ‘personally fought off the Germans, throwing [grenades] from the parapet of the bridge’. Three times Annand returned for a further supply of grenades which he carried in a sandbag before he was hit. Finally, Farr tells us, ‘came the order to withdraw. Dick brought his men out safely. It was then someone yelled to him that his batman [Private Joseph Hunter] was lying wounded near the bridge.’ Miller thinks it was Sergeant O’Neill who alerted Annand to the plight of Joe Hunter, prompting the young lieutenant to return under fire and, despite his own wounds, attempt to bring his batman to safety using a wheelbarrow.21 Sadly he collapsed from loss of blood before he was able to complete his mission and after being evacuated to the battalion aid post at La Tombe was unable to recall where he had left the unfortunate Hunter who was shortly afterwards taken prisoner. Unlike Joe Hunter, Dick Annand survived the fighting on the Dyle to be presented with the VC by King George V on 3 September 1940 – exactly one year after Great Britain had declared war on Germany.

Up until this point the battalion had been in action for over 24 hours and apart from some localized incursions, had held all the attacks made against it and it must have been with a mixture of relief and regret that Lieutenant Colonel Simpson received the order to retire behind the River Lasne at 11.00pm on 15 May. The Durhams’ line had not been broken but events on the right flank in the French First Army sector had opened up a dangerous gap and Blanchard had ordered a retirement to avoid being outflanked. In effect this involved the British I Corps swinging their line back some 6 miles to conform to the French retirement. For the Durhams and the I Corps units dug in along the Dyle their initial surprise was replaced by the realization that the manoeuvre was to be carried out immediately and under the cover of darkness.

Withdrawing from battle positions is hard enough whilst under fire but even more so when the enemy is in close contact. The Durhams had great difficulty in getting away and, despite being supported by the machine guns from C Company of the 2/Manchester Regiment (2/Manchesters), Battalion Headquarters at La Tombe was almost cut off by enemy infantry who had moved forward under cover of darkness. In the fighting withdrawal that ensued, Anthony Lewis and D Company of the Royal Welch Fusiliers also came under fire in what the Manchesters’ historian described as the ‘entangled zone’.22 Not only did the Durhams leave behind twenty-seven of their number, who are recorded in the CWGC database as being killed or missing over the three days of fighting on the Dyle, but the hurried departure meant a considerable quantity of stores and equipment was also left behind. Townsend felt that the battalion’s labours in digging and sandbagging had been in vain and wrote ‘there was not time to send back for the motor transport to come up and take the equipment and stores back. All kit had to be abandoned on the ground.’23

Further south at Wavre the fighting had enveloped the 1st Battalion the Royal Scots (1/Royal Scots) and D Company of the Manchesters who were holding the extreme right of the BEF line. Lieutenant Colonel Harold Money had already adjusted his front line to accommodate the withdrawal of the French 13/ Tirailleurs to the west bank of the river and on 13 May the 5/Field Company had blown the road bridge in the town after the last unit of the 4/7 Dragoon Guards had crossed. Twenty-four hours later the fighting, although ‘firmly repulsed’ was severe enough for Captain James Bruce, the battalion adjutant, to record in his diary that ‘fairly heavy fighting had taken place on the A and C Company fronts.’

The road bridge at Wavre came under scrutiny again by the 2nd Divisional Engineers who, after receiving conflicting reports as to the state of the bridge, instructed Captain Mark Henniker to visit the site to ensure the structure had been properly demolished. Arriving after dark on 14 May to find ‘several buildings were burning and the pavé streets deserted,’ he finally found a company of Royal Scots and a sleepy subaltern called Thorburn ‘with whom I had been a schoolboy long before, who was prepared to vouch for me’. Lieutenant Pat Hunter-Gordon, the subaltern from 5/Field Company who had been responsible for the first demolition, was of the view that not much more could be done and Henniker was of the same opinion: ‘The bridge had leapt into the air from the river bed and returned as a pile of rubble to the river bed again.’ The French expression Faire sauter le pont (make the bridge jump) exactly describes what happened and all that remained to be done was to make it jump again.

As they waited for the 5/Field Company sappers to arrive Henniker and his escort of Royal Scots were only too aware the Germans were just across the river. The fighting had died down but there were still stray shots ricocheting around the square; ahead of them the river bed was practically dry and the remains of the bridge lay in three pieces. It was a case of who would be the first to arrive, Pat Hunter-Gordon or the German Army:

‘Just as we began to fix [the explosives] in place there was an air raid. Dive bombers, Stukas, made a dead set at the bridge, as though they had the same idea as us. We all dived for cover and several houses in the square collapsed in flames ... presently the Stukas departed and Pat led his men back to work. People were popping off rifles and automatics promiscuously from both sides of the river.’24

Eventually, writes Henniker, the bridge was ready for its second demolition and with the sappers safely out of range of falling debris, Hunter-Gordon depressed the exploder handle:

‘There was a terrific explosion. The wreckage of the bridge jumped into the air. Stones, brickbats and bits of steel whistled all over the town, but the main bulk of the bridge eventually settled back more or less where it had come from, only in much smaller pieces ... honour had been satisfied and none of us had been killed.’25

Long after Henniker and the sappers had gone it became obvious to Harold Money that the 13th Indigène Nord Africaine Division on his right flank had retired without the courtesy of informing him. After establishing a defensive flank with B Company and the Carrier Platoon, Money received his orders to retire which placed him in a similar position to the Durhams. ‘This meant very rapid verbal orders and the destruction of a certain amount of equipment.’ Money does not share his thoughts as the battalion marched up the steep hill out of Wavre, preferring to leave James Bruce to write of his disgust at having to leave behind ‘such things as 2-inch Mortars, some anti-tank rifles and in one case Bren Guns [which] had to be destroyed and abandoned’.26 Equipment the battalion would sorely miss in the coming days.

Although the Lasne was a poor substitute for the larger Dyle, the BEF was intact and still full of fighting spirit, their movements now were dictated by a wider strategic picture which had reduced Gamelin’s Plan D to ashes and begun to threaten the whole allied campaign. Unbeknown at the time to British commanders was the extent of the German thrust by Army Group A which had struck the French Second Army at Sedan. German infantry advances late on the 13th had hastened a disorganized French retreat, which 24 hours later, had become a rout. By 16 May armoured columns from Army Group A had advanced so rapidly into French territory that momentarily they lost contact with their headquarters because they had gone beyond field radio range.

Gort issued his orders for a general withdrawal to the line of the River Senne on the night of 16 May having first sent Major General Thomas Eastwood to Caudry to learn of General Billotte’s intentions.27 Even so it was several hours later before these orders were in the hands of battalion commanders. The Ulsters’ move from Louvain was successfully carried out apparently without alerting the enemy which, given the close proximity of the Bala-Tiger post to the enemy, was quite remarkable. Nevertheless, the enemy must have realized a withdrawal was underway as British gunners loudly announced the tactic by expending their stockpiles of shells before falling back behind the armoured regiments.

The Guards withdrawal from Wilsele was a little more problematic. Their positions were under severe pressure from the enemy, the battalion historian observing that ‘the order came as a relief to a battalion holding a position which had already become impossible.’ The ground was far more open than further south in Louvain, continually under enemy observation and swept by machine gun fire. However, in small groups and with the protection of carriers the withdrawal was successfully carried out, the last troops of the 1/Coldstream Guards leaving on the vehicles of the Inniskilling Dragoon Guards.