Chapter Four

Massacre of the Innocents

19–20 May 1940

‘I lay doggo hoping that if night fell soon enough I might creep quietly away. This was not to be as I was finally rolled over by a German, who seemed to be making a very thorough job of examining the wounded. I think I managed a very sickly smile, rather like a small boy caught cheating at school and was promptly confronted by a large revolver.’

L/Cpl Wilson, A Company, 7/Royal Sussex at Amiens.

French Prime Minister Paul Reynaud’s admission of defeat on 15 May was a devastating blow to the British. French high command was in turmoil, the Ninth Army’s demise at Sedan had reduced General Georges to tears and still the German Army Group A was driving west from the Meuse, apparently without opposition. Adding to the weight of depression dogging the headquarters of French supreme commander General Gamelin was the news that Holland had surrendered on 15 May after the bombing of Rotterdam had shattered the will of the Dutch to resist. As Churchill and Dill left Paris after their meeting with Reynaud and Gamelin they had no accurate intelligence of the exact whereabouts of the German panzer divisions but at the Cabinet meeting later that day, the British government – probably for the first time – faced the realistic prospect that France was on the edge of defeat and Britain must either go down with her ally or withdraw and fight on alone. Indeed, as early as 17 May the Admiralty was asked to examine the logistics of assembling small boats in case an evacuation from the Channel beaches became necessary.

The German panzer advance was taking them not towards Paris as first suspected but due west – towards the coast. On 16 May the leading tanks of Heinz Guderian’s XIX Korps covered 40 miles, reaching the River Oise at Guise, while on his right flank, Erwin Rommel’s 7 Panzer Division was within sight of Le Cateau by dawn the next morning. The 17 May saw the first of the German ‘Halt Orders’ issued to the panzer divisions. Although short in duration it underlined Von Rundstedt’s concern as to the vulnerability of his open southern flank and the rapidly extending supply lines that were becoming increasingly challenging. The order, which was lifted the next morning, aggravated an already impatient Guderian who threatened resignation if he was not allowed to continue his advance.

To the south General Georges was desperately attempting to assemble a new army corps to counter the threat from Army Group A that, together with a concerted effort from the north, would pinch out the panzer spearhead – assuming of course the necessary troops could be found. But it was far too late for Gamelin, who was replaced on 19 May by the 73-year-old General Maxime Weygand, the same day that Henri Giraud, the recently appointed commander of the French Seventh Army was captured.1 Meanwhile seven panzer divisions were establishing themselves on the west bank of the Canal du Nord and the only BEF troops that stood between them and the sea were the British 12th and 23rd Divisions.

Private Bert Jones and the 5th Battalion Royal East Kent Regiment (5/Buffs) arrived in France on 20 April 1940. Jones writes with some optimism that their move to Fleury in Normandy would see them beginning their training with 36 Brigade, but if he and his comrades in B Company were expecting to be trained as soldiers they were to be disappointed. Numbered amongst the so-called digging divisions, the 12th Division was put to work building railway sidings around Rouen and developing the Abancourt rail centre.

The 23rd Division was detailed to begin work on airfields around St Pol and Béthune and serving with 1/Tyneside Scottish in 70 Brigade was 18-year-old Private James Laidler who began his army career at Newcastle on 15 March 1940. After a period of basic training the battalion moved to France and young ‘Jim’ found himself at Frévent north of Doullens ‘employed in building an airfield, carrying bags of cement, mixing cement, anything except soldiering’.2 Further south the 46th Division – a duplicate of the 49th (West Riding) Division – was dispatched to Brittany to begin similar tasks around Nantes and St Nazaire. Private Peter Walker joined 137 Brigade in May 1939 and ‘having coughed for the MO’ signed up for service in the 2/7 Duke of Wellington’s Regiment. Within weeks he had been promoted to corporal and in August experienced his first live firing practice. His remaining training consisted of ‘marching around Halifax, doing foot and bayonet drill with and without gas masks’. Nine days after 19-year-old Bert Jones first set foot in France, Peter Walker landed at Cherbourg where his battalion was transported to Blain near Nantes to begin work as loaders for the RASC.3

As far as military training was concerned each man had a rifle and bayonet but any heavier weapons, such as Bren guns and the Boys anti-tank rifle, had in some cases, not been issued and even if issued, they had certainly not been fired by the majority, even in practice. It was a situation that prompted General ‘Tiny’ Ironside to seek assurance from Gort that these men would not be deployed in an operational role until they had at least been issued with their full entitlement of equipment. But as British plans were rapidly overtaken by the speed of the German advance, these early assurances were quickly forgotten as almost every available man was thrown into the front line.

On 12 May Gort’s headquarters received a call from Major General Henry Curtis, commanding the 46th Division, offering his division as a battle-ready formation ready and able to take its place in the line. Incredibly this ridiculous assertion resulted a week later in the division being the first to be called to the front line and incorporated in ‘Macforce’, a formation being put together under the command of Major General Mason-Macfarlane to protect the rear of the BEF. Perhaps of greater significance was the 23rd Division’s move to the line of the Canal du Nord on the instructions of General Georges, an unexpected deployment that Gregory Blaxland felt came ‘as a great shock to the senior General Staff Officer at Arras, Lieutenant Colonel Robert Bridgeman’. The fact that British troops were needed in this French sector was the first indication to British staff officers that Georges had, quite simply, insufficient fighting troops to contain the German breakthrough. Lacking the most basic fighting equipment, the largely untrained 23rd Division was hardly in a position to prevent the German armoured advance even now bearing down on them, particularly as most of the promised French troops failed to arrive.

The movements of the 12th Division were not helped by the absence of their divisional commander, Major General Roderick Petre, who had been summoned to Arras on 18 May to take command of the Arras garrison. Failing to inform the 12th Division that Petre was now commanding ‘Petreforce’, leaving it virtually leaderless, was just one example of a patchwork of ineptitude on the part of the Adjutant-General, Lieutenant General Sir Douglas Brownrigg, commanding BEF (Rear) GHQ at Arras. His ineptitude was to seal the fate of six of the division’s battalions.

By the evening of 18 May the German 1st Panzer Division had reached the Canal du Nord and occupied Péronne where it was engaged by 7/Royal West Kents (RWK) from 36 Brigade which had been reinforced with four 18-pounder field guns cobbled together from the Royal Artillery School of Instruction. Twenty-four hours later the 7th Panzer Division had surrounded Cambrai and was approaching Marquion on the Cambrai-Arras road. As the 8th and 6th Panzer Divisions advanced either side of the Cambrai-Bapaume road towards Inchy-en-Artois and Beaumetz les Cambrai, the 1st Panzer Division was forming a bridgehead over the Canal du Nord at Péronne forcing the 23rd Division to fall back. Kirkup’s 70 Brigade fell back along a 17-mile frontage astride the Arras-Cambrai road and 69 Brigade were ordered to take up positions along the River Scarpe, east of Arras.

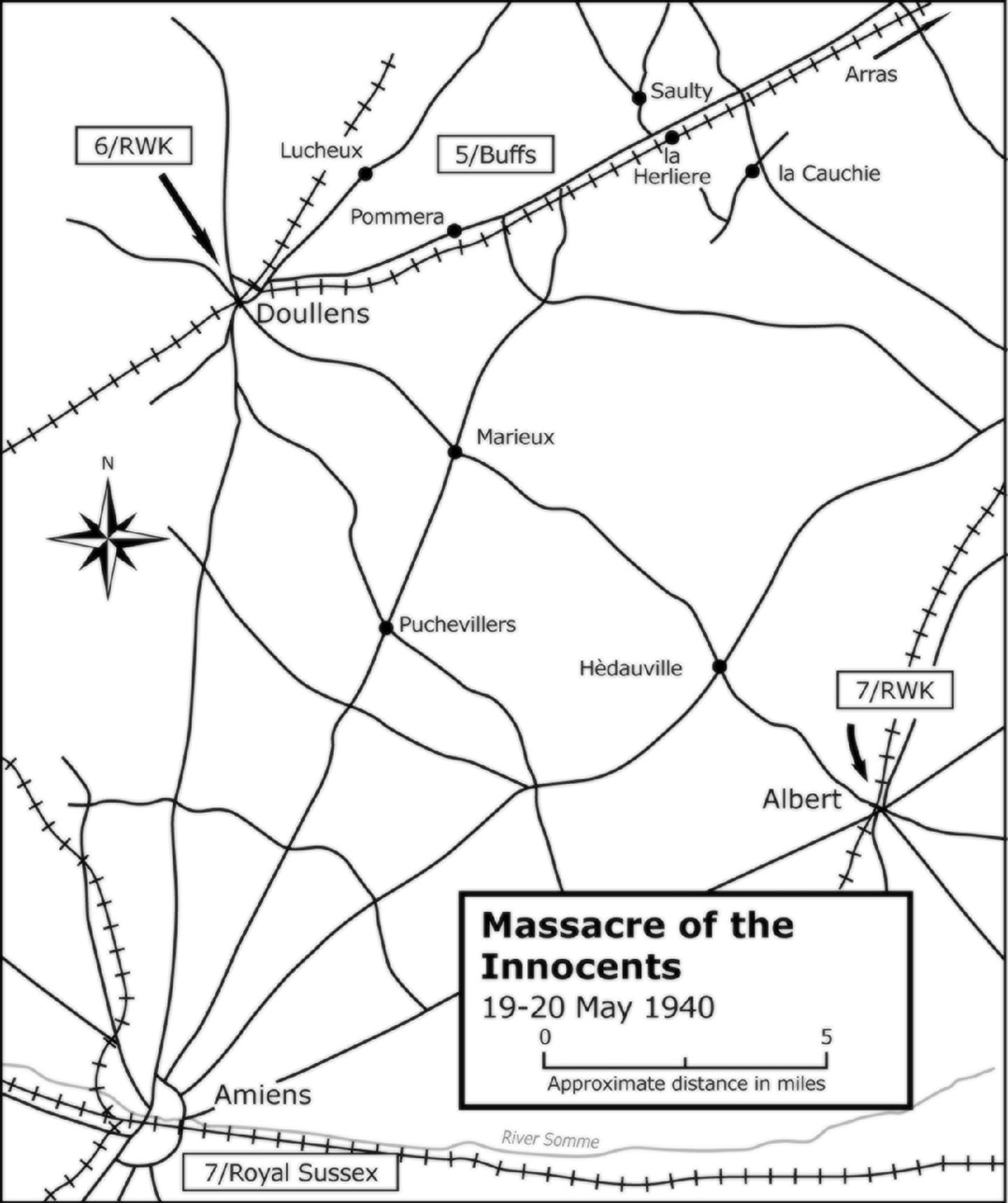

Further south six of the Territorial battalions of the 12th Division were scattered across a wide area which took in part of the old Somme battlefields of 1916. The 6/RWK were strung out along the N29 Doullens-Arras road while the 7/RWK were in the vicinity of Albert. Of the two Royal Sussex battalions in 37 Brigade, the 7th was stranded in Amiens after the train which had been carrying it had been destroyed by enemy aircraft and the 6th was intact but completely isolated at Ailly-sur-Noye – more of which later.

The 7/RWK arrived at Albert in the early hours of 19 May with instructions to take up positions in the town using the River Ancre as an anti-tank obstacle. It was a locality that failed to impress 44-year-old Lieutenant Colonel Basil Clay who felt it was impossible to take up a position along the river as instructed ‘as it was merely a ditch in parts and subterranean in the town’. Reacting to Brigadier George Roupell’s assurance that there were no German forces in the vicinity, Clay moved the battalion to the safety of the high ground northwest of Albert. The move was a short one, curt instructions arrived from Arras at 1.30am on 20 May ordering the battalion back to Albert to ‘hold the position with a view to defence against AFVs’.

As Guderian’s tanks crossed the Canal du Nord early on 20 May, Clay’s men in Albert were being subjected to an attack by enemy aircraft machine gunning the town. Hardly had the smoke and debris of that attack cleared when a German motorcyclist made an appearance on 8 Platoon’s front. Shot at by Sergeant Hill the enemy presence vanished in a hail of fire, but to an old soldier like Clay, who was fighting with the RWK in his second war, the motorcyclist was all the evidence he needed of an imminent attack. With a distinct premonition of trouble he began to issue his orders for the defence of the town.

Another officer who felt uneasy was Captain George Newbery commanding A Company. With hardly enough time to get his company in position on the eastern edge of the town, the arrival of General Friedrich Kirchner’s 1st Panzer Division was announced by a runner from 7 Platoon bringing news of 30 enemy tanks advancing from the direction of Meaulte:

‘I passed the information onto Battalion HQ but before I had a reply, a message arrived from 8 Platoon that twenty tanks were on their front. I looked into the market square to see if the CO was there and found him near the corner. I gave him the information. I cannot remember his reply as an enemy plane swooped on us at that moment. As we took cover an enemy tank entered the square behind us and firing broke out in all directions.’4

It was 6.00am and Basil Clay’s men were all but surrounded: British plans for the defence of Albert were in tatters before the battle had even begun. The opening attack from the south-east fell on D Company whose positions were on the left of the town. It was a brutal engagement in which Captain Edward Hill, the company commander, was killed before the remainder of the company took refuge in a nearby building, defending themselves until the survivors were forced to surrender. As the fighting became more desperate Clay sent out orders for the battalion to withdraw to the transport in the main square – but it was too late for many of the West Kents as enemy tanks burst through their positions demonstrating the absurdity of using Bren guns and rifles to repel an armoured assault.

Those who did manage to reach the transport were instructed to fight their way out and rendezvous at Bouzincourt but very few actually got away. It was in the main square that Second Lieutenant Michael Archer was seen firing a Boys anti-tank rifle under heavy fire and one of the RASC drivers, Private Val Hennam, covered the withdrawal by firing his Bren gun at the advancing tanks, at one point engaging two tanks at short range from the cover of a 30cwt lorry. Miraculously he managed to escape intact still carrying his weapon but later joined Archer in captivity.

Such acts of bravery were, however, to no avail. At 6.10am Second Lieutenant Brown, the battalion adjutant, witnessed the dispatch rider – who he had just sent to 36 Brigade Headquarters carrying news of the German incursion – ‘immediately shot down before leaving the square’ as German tanks ‘arrived almost at once on two sides...making a withdrawal by M[otor] T[ransport] impossible’. Men were cut down by the all enveloping fire and those who were not killed were taken prisoner. Never seriously considered to be a fighting force, the battalion had practically ceased to exist.5 However, Brown’s account notes that three vehicles did manage to escape through the barrier of fire in the square, despite the fact the Germans ‘were shelling and machine gunning at 30 yards range’. Amongst the more fortunate was Captain Newbery:

‘The noise was terrific and it was quite impossible to judge what was happening. We waited ten minutes for 7 Platoon but there was no sign of them. A tank was then heard quite close to our left, so I ordered the 15cwt truck to be manned by PSM Ralph, my runner and two drivers – all that remained – and told the driver to try to pull out.’6

Just after Newbery’s vehicle got away towards Bouzincourt, Brown managed to get clear of the square with Basil Clay and the remaining transport that had evaded destruction. Six miles west of Albert he separated from the column and continued on the pillion seat of a Belgian refugee’s motorcycle until held up by German infantry south of Doullens. ‘At that moment I got on the saddle and rode off. The German fired two shots at me the first of which grazed my knee.’ Despite his wound and running out of petrol, Brown evaded capture and eventually returned to England. Clay was amongst those who were later rounded up and taken prisoner but George Newbery and a party of seventy men did reach Boulogne. It was another six years before Michael Archer’s MC and Val Hennam’s MM were announced.

The experience of the two Royal Sussex battalions of 37 Brigade was typical of the disorganization that appeared to cloud the judgement of the 12th Divisional staff. On 18 May the 7/Royal Sussex, 263/Field Company and 182/Field Ambulance were met by Brigadier Richard Wyatt who gave verbal orders for the battalion to entrain for Lens. Routed towards Amiens the train was stopped just short of the station at St Roche on the western edge of the city before it slowly inched its way forward:

‘The long train had hardly pulled into the station when it was attacked. The men were travelling in cattle trucks (about 40 in each) and most of them were lying asleep with their boots off, having been advised to get as much sleep as possible. The first thing they knew was being awakened by a heavy explosion at the front end of the train at 15.15 [3.15pm] hours. Then they heard the drone of dive-bombers and bursts of machine-gun fire. The train had been run into a siding and the engine had stopped at the buffer-stops, so it was a stationary target.’7

Travelling some distance behind was the train carrying 6/Royal Sussex and 264/ Field Company which fortunately avoided the air attack and was run into the relative safety of a cutting where it remained until 6.30pm. Avoiding the carnage at St Roche the 6/Royal Sussex eventually continued to Ailly-sur-Noye where a lack of orders prompted them to continue to Paris where they were directed to Nantes to resume their labouring.

On board the 7/Royal Sussex train was Private Doug Swift, a 21-year-old gardener from Eastbourne. Called up in January 1940 he was in France four months later with 37 Brigade at Forges-les-Eaux, a small town 15 miles southwest of Aumale. Swift, like many of his comrades in A Company had not seen any reason to complete the will in the back of his pay book, reasoning that as a labour battalion there was little need. He was in for a rude awakening. Swift recalled the bombs falling and exploding amongst the trucks and sending showers of debris flying high into the air. ‘We scrambled out of the trucks, diving underneath just before the Stukas came screaming down for a second attack, followed by a third.’

According to French historian Jacques Mercier one bomb fell between the tender and the first coach containing all the officers, killing ten and wounding, amongst others, Lieutenant Colonel Ronald Gethen the commanding officer. Gethen’s account documents another twenty-five other ranks killed during the attack and some eighty more wounded, many of these wounded were taken to the nearby Hotel Dieu and treated by a French medical officer, Captain Lemoine, and 182/Field Ambulance staff. Once the wounded had been taken care of, Gethen’s next priority was to move the remaining men to the shelter of a nearby wooded area around the Château Blanc a mile to the southwest on the Amiens-Poix road.8

Travelling on another troop train towards St Roche behind the Royal Sussex was Major Graeme Dalglish on his way to join the 1/8 Lancashire Fusiliers who were fighting with the 2nd Division. The first indication of trouble came at 2.30pm when German aircraft began bombing Amiens and Dalglish’s train was shunted into a siding between two ammunition trains east of Pont-de-Metz! With the line ahead blocked and with little prospect of any further movement until the next morning, the train was evacuated.

Meanwhile Gethen had managed to contact British headquarters in Amiens and before long a staff officer arrived but was unable to offer much practical assistance. Irritated by the inability of the staff officer to provide further orders Gethen informed his own officers that without further orders he intended to stay put. His situation was augmented by the addition of Major Dalglish’s party which had by this time boarded a second train, only to be frustrated again at St Roche by yet another German air raid which blocked the line and destroyed the train. ‘This was my first taste of dive bombing’, wrote Dalglish, ‘an unpleasant experience when it is such a one-sided show, as we had no LMGs [light machine guns] or rifle ammunition and as far as I could see there was no AA [anti-aircraft] fire of any kind.’9

At the Château Blanc the remaining men of the Sussex began to dig in and Second Lieutenant Garrick Bowyer was ordered by Gethen to establish a road block on the Poix road with his platoon which, apart from a single light tank, failed to persuade any retreating French infantry to remain with the Sussex. There is certainly some suggestion in the war diary account that Gethen was suffering from the effects of his head wound. This manifested itself in the form of flat denials – despite evidence to the contrary – of any enemy presence in the immediate area; whether his behaviour in this respect was an attempt to maintain the morale of his men and dispel any rumours we shall probably never know.

However, persistent reports from retiring French infantry of German forces heading in Gethen’s direction could not be ignored. It was becoming clear to all concerned that there was an element of truth in the assertions, particularly after Major Dalglish observed enemy shells bursting on a ridge near the Amiens-Paris road about 11.00am on the morning of 20 May. Reporting this to Ronald Gethen he was dismissed by the irate colonel who accused him of ‘romancing’ but by this time Gethen must have realised that all was not well as Dalglish noted the Sussex positions were quickly changed to one of all round defence.

At 2.00pm machine-gun fire was heard on the right flank and Second Lieutenant Bower, who commanded 5 Platoon in B Company, watched as German tanks began to engage A and D Companies which were forward of the château grounds in the open fields to the north. This was the vanguard of Kirchner’s 1st Panzer Division who had travelled the 17 miles from Albert and were en-route to the coast. Doug Swift remembered that the attack on A Company came almost without warning: ‘A hail of machine-gun bullets came sweeping down amongst us from German tanks on the top road ... They were also hitting the château with heavy mortars causing considerable damage and the farm buildings on our right were on fire.’ Moving forward to get a closer view of the battle now developing around the farm buildings, Bowyer and his company commander, Major Peter Miller, came under enemy machine-gun fire. Bowyer was wounded in the leg but managed to return to the Poix road where he witnessed Peter Miller’s death in a shamefully unequal duel: tank versus revolver. Gethen’s account provides more of a flavour of the battle as it unfolded:

‘About this time [3.15pm] the CO received a verbal message from A Company reporting they were pinned down by enemy MG, snipers and tanks. The CO and 2iC [Major James Cassels] reviewed the ground between the Amiens-Poix road and A Company and the farm. A good deal of fire of all sorts and one enemy tank visible ... Decide to relieve pressure on A Company and drive out the enemy from their position by the advance of HQ Company, B Company to conform from the right flank ... French tank got forward of the haystack in view of enemy tanks and it actually opened fire. The battle developed for probably an hour longer – until about 5.15pm when it seems tanks came right forward and cleaned up the remainder of HQ and B Company.’10

A Company did not actually surrender until 6.15pm by which time Gethen had organised the reserve platoon of C Company to reinforce the beleaguered B Company, but the battle was almost over and Gethen was moments away from being taken prisoner. Dalglish writes that he and another officer – a Major Stannus en-route to join 1/6 Lancashire Fusiliers – attempted to reach the Sussex positions on both flanks but failed: ‘As we attempted to move we got plastered with everything ... to make things worse five light tanks had got round behind us on the slope the other side of the Amiens road and were firing into our backs.’ Both officers were in the château grounds and in all probability witnessed Gethen and the remnants of the battalion he had rounded up, fix bayonets and advance across the fields towards the German tanks. It was the final act of defiance before the survivors were swept into oblivion or captivity.

The casualties had been horrendous. Pitted against tanks with no heavy weaponry and only lightly armed, the Sussex had been outgunned and out-manoeuvred by their German counterparts. In A Company alone only two men were left unwounded while overall there are at least 132 officers and men listed on the CWGC database as having being killed between 18–20 May or died of wounds later. Although some 160 officers and men, including Ronald Gethen, were taken prisoner, many did manage to escape and of these Garrick Bower was picked up by a French unit days later and finally managed to return to England. Major James Cassels initially escaped with Dalglish, but was later found shot near Aumale while Dalglish and his party stumbled into a patrol of the South Lancs and embarked for England on 4 June 1940.11

We must now move 18 miles north of Amiens to Doullens where 6/RWK under the command of Lieutenant Colonel William Nash arrived on 18 May after an exhausting eleven hour journey. In the town Nash found Lieutenant Colonel Hudson Allen and the 5/Buffs with Brigadier George Roupell who was waiting to give both battalion commanders new orders to move up to the La Bassée Canal. The 48-year-old Roupell was a First World War veteran and had been awarded the VC during the action on Hill 60 at Ypres in April 1915, but even he must have wondered if there was any clear overall strategy in place when these orders were rescinded an hour later, both battalions being instructed instead to remain in Doullens and construct road blocks at all the entrances to the town. According to Nash this was a process that was hampered by instructions not to crater the roads or fell any trees so as not to impede the retirement of the French!

Shortly after midnight on 20 May the movement orders were changed twice more forcing Nash to finally visit brigade headquarters for confirmation, resulting in the order Bert Jones was eventually given by his platoon commander to move out along the road to Arras:

‘We moved up the Doullens-Arras road to take positions between Pommera and La Herliere. The road was choked with refugees blocking the way, but we [B Company] managed to get into place by the morning. We were very poorly equipped; besides our old Lee Enfield rifles we had a couple of Bren guns and a .55-inch Boys anti-tank rifle and a 2-inch trench-mortar.’12

If the Buffs considered themselves poorly equipped then the West Kents could scarcely be considered better off. According to Lieutenant Colonel Nash the only weapons the battalion possessed – apart from personal Lee Enfield rifles – were:

‘16 Bren guns and 12 Boys rifles: no hand grenades had been issued. Officers were not in possession of revolvers or maps and only a few had compasses. Very few NCOs or men had ever had an opportunity of firing an A/T rifle and some men, drafted to the battalion on the eve of proceeding overseas, of firing any weapon previous to going into action.’13

It was hardly a recipe for success, particularly as the battalion was now in the path of Georg-Hans Reinhardt’s XLI Korps whose 6th and 8th Panzer Divisions were equipped with the heavier Czech designed Panzerkampfwagen 38(t) tanks.

News of the demise of the 7/RWKs at Albert arrived at 36 Brigade Headquarters in the form of a gunner officer, Second Lieutenant Larner, reporting the destruction of the four 18-pounders in the main square and heavy casualties. Shortly after this brigade headquarters was moved to the medieval château at Lucheux and Nash established his battle headquarters at Grouches-Luchuel. Three hours later shellfire from the direction of the D938 Albert road began to strike the roadblocks held by B and C Companies on the Arras road, while D Company, whose front extended from Beaurepaire Farm to the crossroads with the D24 west of Pommera, was attacked from the air. The battle was about to begin.

During the next hour tanks and troops with machine guns appeared from all sides, infiltrating along main and minor roads from the direction of Arras and Albert putting B Company and the HQ Company roadblock at the junction of the Albert-Amiens road under pressure. Temporary respite was achieved at this roadblock when Second Lieutenant Pugh disabled the lead tank with a round from a Boys rifle and the enemy infantry attack was driven off by a party led by Captain Phillip Scott-Martin.

At 1.30pm the B Echelon transport managed to get away along the Abbeville road before the net began to close in around the town. Shortly afterwards battalion headquarters at Grouches came under attack, first by a single tank and later by a group of four of five, before they continued towards Doullens. Lieutenant Colonel Nash’s diary records the final stages of the fight put up by the West Kents:

‘By 2.30pm enemy AFVs appeared on the high ground both on the north and south of Doullens, but made no immediate attack, but as the houses occupied at the junction of the Albert and Amiens roads were now burning fiercely, they had to be evacuated and Captain Scott-Martin was obliged to withdraw his company [HQ Company] to the western side of the town. By 3.00pm the attack on the north side of Doullens developed and 2/Lt Henchie’s road block on the St Pol-Arras road came under heavy mortar and 2-pounder fire and by 3.30pm 2/Lt Waters’ platoon on the St Pol road was in action against enemy medium tanks and infantry. By 4.30pm D Company had been completely surrounded and their left platoon had suffered considerable casualties and all the Doullens road blocks had been under heavy fire.’14

By 5.00pm the situation of the West Kents was critical as the surviving soldiers gradually withdrew to A Company headquarters on the Rue de Bourg near the main square. Completely surrounded and under heavy fire from tanks and machine guns, Captain Scott-Martin surrendered the remnants of the battalion at 8.30pm. Casualty figures are still difficult to ascertain. It would appear that no officers were killed during the engagement, and while several managed to get away with small parties of men, they were largely rounded up – in some cases days later – and taken prisoner. The CWGC database records twenty NCOs and men killed between 20–21 May and these are now buried at Doullens Communal Cemetery Extension No.1. At least sixteen officers were eventually taken prisoner including the commanding officer and although seventy-four officers and men returned to England some 503 were posted as missing.

Lieutenant Colonel Hudson Allen, commanding 5/Buffs, had little choice but to create islands of defence along his 6½ -mile section of the Doullens-Arras road with his own headquarters in the small hamlet of La Bellevue. Running parallel and to the south of the road was the Achicourt-Doullens railway line which, in the absence of anything better, Roupell hoped would serve as some sort of anti-tank barrier. Roupell might not have considered Allen’s battalion able enough to delay the panzer advance for any significant time but the comparative ease with which the battalion was overcome when it finally came under attack is almost shocking. The railway line offered little or no resistance to enemy tanks and although it was established much later that B Company at l’Arbret held out until 3.15pm, the Buffs were effectively swept aside by the German armoured attack.

At l’Arbret the company transport was parked near the mill where the modern day abattoir now stands and B Company set up its headquarters in the railway station building with 12 Platoon dug in between the railway and the main N25 road. Private Bert Jones was on the attic floor of the railway station on watch with Captain Rawlings:

‘From our vantage point we could see right across the fields to the south. The first sign of trouble was light glinting on metal. We could see lots of movement, and what looked like large numbers of vehicles moving along a road to the south. We reported to the officer [presumably Captain Rawlings], but he told us that it must be another refugee column, after all, the main German advance was supposed to be well away to the north of us.’15

What Jones had seen was the advance of the 8th Panzer Division along the D1 at la Cauchie and it wasn’t long before tanks were soon heading across the fields towards them. Lieutenant Colonel Allen’s diary records that this information arrived at battalion headquarters at midday, at the same time as Captain Hilton’s message reporting enemy shelling and tanks on C Company’s front. The enemy attack was evidently enveloping the whole of the Buffs’ defence line simultaneously.

According to Allen the forward platoon of B Company became engaged with enemy tanks at 1.15pm which, according to Jones, prompted men – probably of 10 and 11 Platoons – to retire swiftly to the railway buildings. André Colliot, a local French historian, writes that a single British soldier was left seriously wounded in the field and was later picked up by a German ambulance. Whether it was around this time that Corporal Alfred Carpenter took on two German tanks is unclear but firing the Boys anti-tank rifle for the first time he only withdrew after all his ammunition had been used. Attention was then directed towards the station:

‘One German tank drove down the street towards the railway station. A corporal called Ratcliffe [E Ratcliffe] I believe, opened fire on the advancing tank. I was told that he lost an eye, but was otherwise OK as far as I know. [Private] Sid Bartlett and I were still inside the station and I ran outside to drag a large box of .303 ammunition into the station. However, when the Germans started firing in our direction I thought it more prudent to get back in the station.’16

In his account, Jones fails to mention Sergeant William Elson who, according to his citation for the MM, held the station with two rifle sections, repulsing two German attacks on the building and holding up the German advance for two hours. This suggests that Jones and Sid Bartlett got out of the back of the station before the final attacks. Crossing over the railway line they crawled into the long grass on the far side: ‘While we lay there a German tank drove up the railway line and passed right beside us.’ Ignoring the temptation to shoot the tank commander they watched German soldiers searching the abandoned goods wagons in the railway siding before setting off with three others to locate the remaining companies.

Neither Lieutenant Colonel Allen’s diary nor Jones’ account mention the heroic stand of Private John Lungley who had taken up position a few yards west of the D23E Saulty road. In the account given by the station master to André Colliot, Lungly’s Bren gun fire held up the German advance and prevented their access to the Saulty road – this must have been around the time Elson was still fighting from the confines of the railway station. The station master remembers a German light armoured vehicle armed with two machine guns being brought up to machine gun Lungley’s position at about 1.45pm. ‘The firing ceased, a brave man was no longer.’17 Carpenter and Elson’s MMs were gazetted in 1945 but John Lungley’s contribution went unrecognised although he is still remembered in the village and his grave in the nearby communal cemetery is often visited.

By 2.15pm the enemy had penetrated the gap between A and C Company and B Company was reported to be cut off. Allen’s diary tells us it was at this point that he sent out orders for the battalion to withdraw north towards Lucheux but in the event only D Company and Major Tom Penlington with HQ Company managed to escape. Moving across country Lieutenant Colonel Allen and party reached Lucheux at 4.00pm:

‘On arrival there the CO informed the brigadier of the situation and his reason for withdrawing. It appears that the brigadier did not realize the strength of the attack and appeared to think that only a few tanks were attacking. At this time a report was received that enemy tanks were in Gruche (HQ 6/RWK). A defensive position was taken up at the Château. About 6.30pm a light tank arrived in the square in front of Bde HQ and this was put out of action.’18

The tank was hit by Private John Dexter of D Company who had been posted at the gate with instructions to cover the approach to the château. Opening fire with a Boys anti-tank gun – a weapon Dexter had never before fired – he hit the first tank before reloading and hitting another. His award of the MM was also announced in 1945. At 8.00pm Roupell ordered the château to be evacuated and the group were ordered to split into small parties and attempt to get back to British lines. Allen and his party were later captured but Roupell and Captain Charles Gilbert, his brigade major, found their way to Rouen and spent nearly 15 months hiding on a farm before eventually escaping over the Pyrenees. The 5/Buffs had effectively ceased to exist, only 5 officers and 74 other ranks from C Company managed to return to England, the remainder were either killed or captured.19 As for Bert Jones and Sid Bartlett, they remained at large until 17 June before they were taken prisoner near Namur.

If George Roupell had harboured any thoughts of units from the 23rd Division arriving in time to reinforce the Buffs along the Arras-Doullens road he was greatly disappointed. On 19 May the division was approximately 6 miles west of Cambrai along the Canal du Nord; 24 hours later, after their movement orders had been changed on four occasions, 70 Brigade was diverted from Thelus, north of Arras, to the Beaumetz – Saulty area from where they were to make contact with Roupell’s 36 Brigade. As their route took them in a southwestly direction, Jim Laidler, marching with 1/Tyneside Scottish (The Black Watch), felt as if they had been marching ‘all day and all night’. Thus as dawn broke on 20 May 1/Tyneside Scottish were at Neuville-Vitasse, 10/DLI at Mercatel and 11/DLI at Wancourt. Here at least there was some respite, with the nearest unit of the Buffs some 20 miles away to the west 47-year-old Brigadier Phillip Kirkup gave orders for the three battalions to rest while the RASC transport drove on ahead, dumped their loads and returned to assist in ferrying the infantry columns to their new destinations.

In command of 1/Tyneside Scottish was Lieutenant Colonel Hugh Swinburne who, prior to his promotion, had been second-in-command of the 9/DLI. Evidence suggests that he was a man who didn’t suffer fools gladly and defined a fool as anyone who failed to live up to his expectations. His account of the battle – which was written post-war – conflicts with the ‘official version’ submitted by Captain John Burr as part of the war diary. Burr’s account contains numerous corrections and additions in Swinburne’s handwriting, one of which openly criticises the length of time the transport took in reaching Saulty and returning to Neuville-Vitasse. Swinburne writes they left at 3.00am and did not return from the 30-mile round trip until 9.00am that morning, citing this as a principle cause of the battalion’s misfortune.20

Swinburne may well have been correct in his assertion but in mitigation author Tim Lynch suggests that the battalion transport was inevitably moving at the pace of the slowest vehicle on narrow country roads and possibly without the current editions of local maps. In addition the reliability of the vehicles – many being hired ex-civilian transport – was uncertain and the roads were undoubtedly heavily congested with refugee traffic. However, it must be said that two companies of the 11/DLI were successfully ferried into Beaumetz-les-Loges by 5.00am – leaving Lieutenant Colonel John Bramwell with the remaining men at Wancourt. The distance was certainly shorter and whether their transport used a different route or was subjected to less refugee traffic is anyone’s guess but, given the circumstances, Swinburne’s criticism appears at the very least to be unfair.

Back at Neuville-Vitasse passing refugees had informed Swinburne at 6.50am of the presence of German tanks in the vicinity prompting him to give the order for the battalion to march towards Mercatel, each company moving through the other in a leapfrogging movement. With the battalion now on the move Swinburne left them to make contact with brigade HQ at Barly with a convoy of seven vehicles containing HQ Company and an assortment of men of the Pioneer Corps who had been picked up at Neuville-Vitasse.21

At approximately 9.15am Swinburne’s party was ambushed in Ficheux by the 8/Motorised Battalion from Kuntzen’s 8th Panzer Division and the lead vehicle containing Swinburne was immediately set on fire. Private Malcolm Armstrong remembered being in the rear of his vehicle and shouting for his mate Arthur Todhunter to get out:

‘He couldn’t as he was already dead. There was panic everywhere. I went round to the left and saw a small tank approaching. We were given orders to fix bayonets to attack. Surprised, I noticed that the cannon turned towards me but I escaped death when he changed direction, fired and one of the other lads fell. With Private Albert Foster, who was killed later, we advanced along the side of the Pronier Farm. I was going to go in when a bullet or something similar struck my rifle and I dropped it. As I bent down to pick it up I was again saved when something just missed me. I then ran to an area behind this building and saw a dozen of my comrades mown down by machine-gun fire.’22

To Private Jim Laidler it felt as if the Germans had thrown ‘everything possible at us – mortars, tanks, machine-gun fire and rifles. Our casualties were terrific. Out of 300 men who had arrived at Ficheaux, 150 were killed and many others wounded.’

Unaware of the disaster that had already overrtaken his battalion in the shape of the 7th Panzer Division, which had broken through south of Arras, Swinburne evaded capture for 48 hours before he was eventually taken prisoner at Avesnesles-Comptes. In the meantime C Company – still at Neuville-Vitasse – had been surprised by an attack on both flanks at 8.15am. With ammunition expended and the line of withdrawal cut off on three sides, all were either killed or captured.

Having just passed through C Company – and realising Captain George Harker and C Company were under attack – Captain Esmond Adams commanding D Company, decided to remain with one platoon to assist Harker if necessary, while the remainder continued on towards the Arras-Albert railway line and battalion headquarters. Using commandeered vehicles, Adams soon rejoined the company, arriving just after Swinburne’s party drove into the ambush. Leading his men round the right flank towards the firing they were eventually pinned down by enemy tanks and after heavy casualties had depleted his force, Adams split the survivors into small groups in the hope that they might evade capture.

It was now the turn of A Company, under the command of Captain Hilton Maugham, which had passed over the road junction at Mercatel and was moving towards the Arras-Albert railway line when enemy AFVs closed in on both flanks, catching the company in open ground. Despite anti-tank rifles being deployed the fight was over almost before it had begun. Half a mile up the road B Company had crossed the railway line where it came under hostile fire from the direction of Ficheux. A former soldier with the Machine Gun Corps in the previous war, 43-year-old Company Sergeant Major (CSM) Charles Baggs could see his men fighting with tanks all around them:

‘What a terrible sight ... a German machine gun opened out on my left flank simply raking us with MG fire, and to complete his work, two tanks came up behind us and positioned themselves about 20 yards away. They opened out with their shells, and simply blasted us out of the [railway] embankment. We were at last surrounded, and within a minute or two, I had 14 killed and 6 wounded. To hear those lads moaning made me rather sick.’23

As the battle became fragmented many of the Tynesiders continued fighting in the face of enormous odds. Provost Sergeant Dick Chambers was killed as he attempted to fire through the slits in a tank turret, Lance Corporal Frederick Laidler – no relation to Jim Laidler – continued to play his pipes until he was shot down and CSMs Alfred Parmenter and John Morris took over Boys anti-tank rifles after their crews had been killed until they too were overrun.

Two companies of the 10/DLI had also been caught on the outskirts of Ficheux. Not a single survivor remained from Captain John Kipling’s C Company but the few survivors from B Company that managed to extricate themselves included Captain George Robinson and Private George Walton who finally reached the coast on 2 June. Both were captured two days later as they were launching a boat out to sea. The 11/DLI had also been hit hard by Rommel’s 7th Panzers at Wancourt and, after a short engagement, were all either killed or captured. In due course the surviving Durhams were gathered together by Lieutenant Colonel David Marley commanding 10/DLI at Lattre-St-Quentin. When 70 Brigade finally reconvened at Houdain a few days later only 233 officers and men answered their names.24

If the 36 Brigade orders had lacked clarity then those issued to 35 Brigade smacked of almost total incompetence. Consisting of three Queen’s Royal Regiment (West Surrey) battalions, they had been labouring at Abancourt since mid-April. On 17 May the 2/6 and 2/7 Queen’s – possibly mistaken by Movement Control for the 46th Division – were ordered to Abbeville where they were surprised to discover they had been diverted to Lens. Reaching Lens in the midst of an air raid they learned to their dismay that the original orders had been a mistake and they were to return to Abbeville where at least they were reunited with the 2/5 Queens. On 20 May it was decided to withdraw the brigade across the Somme, but in the confusion of the 2nd Panzer Division assault on Abbeville, Brigadier Vivian Cordova’s orders went astray.

Trouble began when Lieutenant Colonel Edward Bolton commanding the 2/6 Queens, noted that the tanks he had seen crossing the airfield south east of le Plessiel were not British, as first thought, but German, and what’s more, were heading for the mouth of the Somme. Having failed to make contact with the 2/7 Queens he wisely decided to lie low and remain where he was until darkness fell before he led the battalion across the Somme at Port-le-Grand. Apart from the rearguard platoon, which was surprised by German tanks crossing the St Omer road, the battalion was south of the river by dawn.

The 2/7 was less fortunate. Deployed around Vauchelles the same German tanks were first seen approaching the lines at 5.30pm and after a short engagement with all the available anti-tank ammunition Lieutenant Colonel Francis Girling gave orders to retire. In the confusion of battle those orders only reached HQ Company in addition to two platoons which succeeded in crossing the river, the remainder being killed or captured. The only battalion that received Cordova’s orders to retire was the 2/5 which was told to wait until the 2/7 had crossed the Somme before moving. The battalion was eventually split into small groups by Lieutenant Colonel Alex Young and told to make their own way to the river. About 120 officers and men escaped death or captivity. By midnight on 20 May 35 Brigade had practically ceased to exist as a viable formation, a tragedy that may have been avoided if the 6 and 7/Royal Sussex battalions had been deployed on the south bank of the Somme opposite Abbeville as originally intended, where they might have been able to assist the Queen’s brigade by holding the high ground which overlooks Abbeville from the south.

Corporal Peter Walker’s adventures with the 2/7 Duke of Wellington’s Regiment began on 18 May when the battalion left St Nazaire by train for Arras via Amiens. After several delays around Rouen their destination was altered to Béthune. Walker’s account betrays the almost total confusion caused by the fast approaching panzer divisions:

‘The battalion travelled to Rouen and met up with the rest of 137 Brigade and another battalion, the 2/4 KOYLI from 138 Brigade. They were bound for Béthune via Amiens but the railway bridge over the Somme had been destroyed by the enemy so were diverted [with us] through Dieppe to Abbeville.’25

Eventually four trains were travelling in convoy towards Abbeville, Walker and the 2/7 were in the last train with the 271/Field Company sappers:

‘In the near distance the bombing and fires in Abbeville could plainly be seen and it became obvious the Germans had occupied the town. The only way we could go now was backwards towards Dieppe. The KOYLI made their way back on foot. The trains carrying the [2/5 & 2/7] Duke of Wellingtons had come to a halt on an embankment and could not be unloaded without being moved and to make matters worse, night had fallen and it had become dark.’26

Unbeknown to Walker the first train carrying the 2/5 West Yorkshires and 137 Brigade Headquarters staff had carried straight on through Abbeville and finally ended up at Béthune on 21 May. Meanwhile, 11 miles west of Abbeville at Chépy, the Dukes had unloaded two utility trucks and dispatched reconnaissance parties to get some idea of exactly what was taking place around them. The death of Second Lieutenant Kenneth Smith near Abbeville confirmed that the town was in enemy hands prompting Lieutenant Colonel George Taylor to deploy the battalion in a defensive position around the train. As Walker recounts, they were hardly in a position to meet a determined German attack:

‘The position took the form of a line of soldiers lying on the ground armed with a rifle and 50 rounds of small arms ammunition per man, with a Bren gun, with only one magazine per platoon. We were lying flat on the ground, because we had neither pick, shovel nor entrenching tool.’27

Given the options open to him, Taylor had little choice but to withdraw on foot in the direction of Eu to find a better defensive position. But fortune was clearly smiling as at Fressenville, behind a jumble of wreckage, they discovered two trains that had remained intact:

‘We were, however, able to free some horses from what was evidently a train transporting either French or Belgian cavalry ... a dog which we freed from the train quickly became attached to the battalion and they say it remained with us to the end. The last train was a hospital train containing French wounded. The CO promised to get help and the battalion took up a defensive position in a wood near the railway line.’28

Eventually the line was cleared with assistance from a large crane and on 27 May the battalion steamed into Dieppe. Peter Walker was wounded and captured on 10 June at the seaside town of Veules-les-Roses while waiting to be evacuated.

The German advance to the channel coast had not only deprived Curtis of a large proportion of the 46th Division by effectively cutting the Allied armies in half but had destroyed 70 Brigade in the process. The 21 May also marked the end of the 12th Division’s war. It is hard to find another division that was so badly led and deployed and while there is little doubt that the 12th Division would have eventually been sucked into the battle regardless, it was certainly not fit to engage anything like a panzer korps. The loss of six of the division’s nine battalions in a single day was an appalling tally that might have been significantly reduced if these raw Territorials had been used to maintain a house-to-house defence of Amiens and Abbeville such as the Home Guard was trained to carry out after the Dunkirk evacuation – but in May 1940 that was unimaginable!

Gort, now faced with the urgent need to strengthen his line on the southern front, ordered two divisions to move south, the 50th Division occupied the Vimy Ridge on 19 May and were joined by the 5th Division and 1 Tank Brigade a day later. Major General Howard Franklyn now assumed command of these units which, together, bore his name and would fight as ‘Frankforce’.