Chapter Five

The Escaut

19–23 May 1940

‘News from the south reassuring. We stand and fight. Tell your men.’

Message from Lord Gort on 21 May to all units on the Escaut.

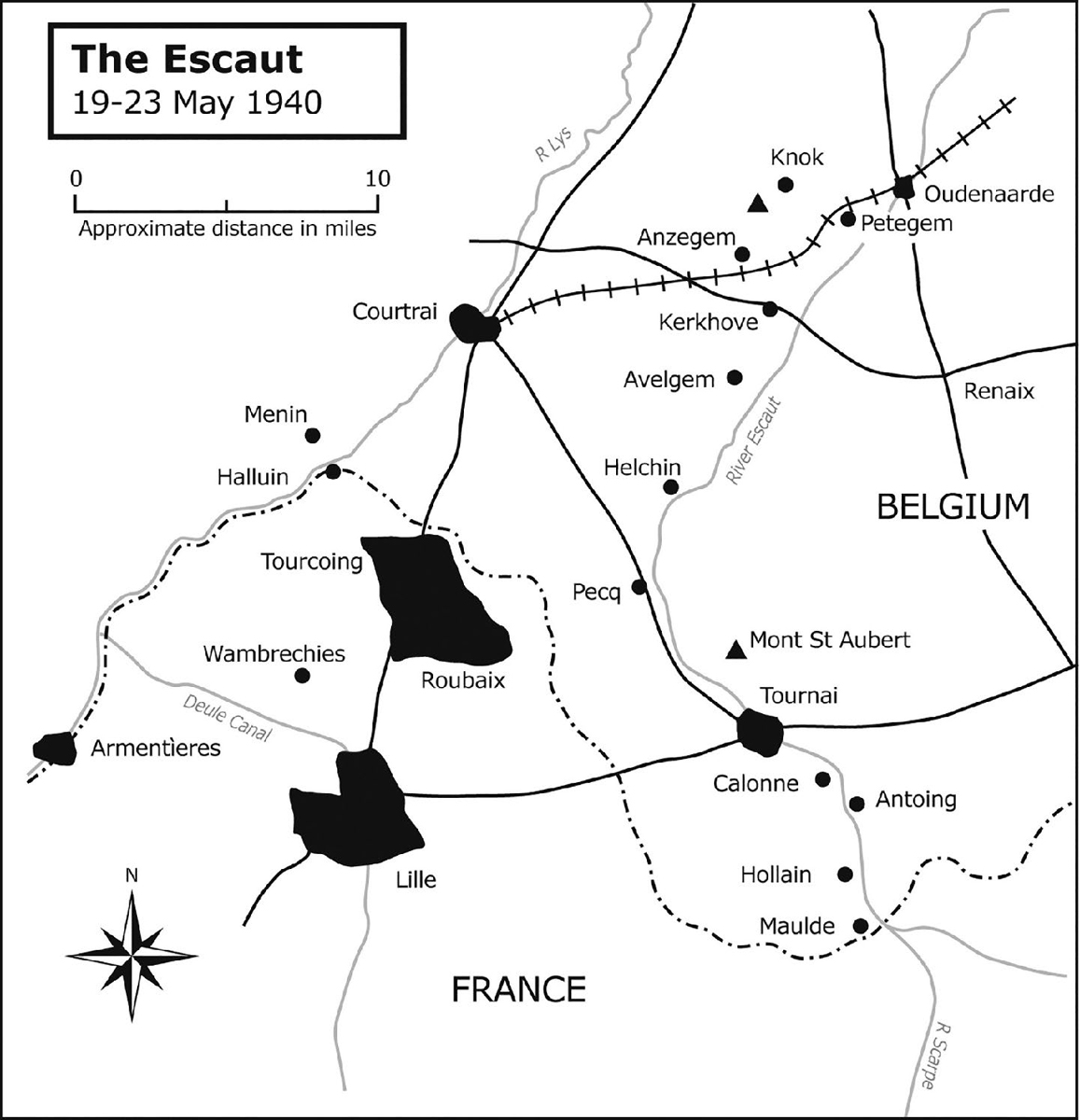

Even as ‘Frankforce’ was being formed at Arras, 53 miles to the north-east the 44th (Home Counties) Division, under the command of 55-year-old Major General Edmund ‘Sigs’ Osborne, began arriving on the Escaut on 14 May. Osborne, a former Royal Engineers officer, was commanding the extreme left of the BEF at the junction with the Belgian Army. With the ridge of high ground between Anzegem and Knok centre stage in his sector, he was left in no doubt by Sir Ronald Adam that the high ground was of critical importance: its loss to the enemy would compromise the whole Escaut position.1

Given the critical nature of his sector, Osborne’s deployment focused on localities rather than a more continuous line of defence, which certainly raised eyebrows at the time and continues to be questioned today. Placing 132 (Royal West Kent) Brigade on the left flank and 131 (Queen’s) Brigade on the right, he left Brigadier Noel Whitty’s 133 (Royal Sussex) Brigade in reserve around Knock. With four battalions on the canal and another five behind, his dispositions looked fine on paper but as Gregory Blaxland remarked in Destination Dunkirk, Osborne’s strategy ‘provided the least firepower forward’.

The Escaut was some twenty yards wide and ten feet in depth with the tow paths ten feet above the water, effectively obscuring any meaningful observation of the last 300 yards on the opposite bank. Even with the forward posts on the tow path itself, observation was still limited. The first contact with the enemy came at 10.00am on 19 May, not from across the river, but from the air as Stukas attacked the bridges at Eine and Oudenaarde and the railway station, providing 132 Brigade with their first battle casualties of the war. Lieutenant Colonel Arthur Chitty, commanding the 4/RWK, recalled thirty bombs being dropped and an ammunition truck parked on the bridge being completely obliterated along with the personnel of an artillery observation post. The other casualties were noted by Captain Stanley Clark to be mainly from A and B Companies who were in the forward posts near the bridges:

‘It was a nasty shake up and our first taste of war, but there was too much to do to repair the damage done to think then. The brigade commander ordered the bridges to be blown and by the afternoon there was no contact from the other side ... that evening several shells fell near the town and the first sight was seen of the enemy.’2

It was not until the next morning that the first German soldiers appeared in any real force and were dealt with by a C Company patrol led by Lance Corporal Brookes who crossed the river and returned with a prisoner. But the German breakthrough came two miles downstream in the 2/Buffs sector.

The Buffs held a frontage of over 2,500 yards and although they were half a mile from the river itself, a drainage canal running in front of their positions was considered enough to stop German armoured vehicles. At 12.30pm the first German units were seen on the hill behind Melden, a presence which developed into artillery fire by late afternoon and an attempted crossing of the river was reported by A Company in the vicinity of the canal loop to the south west. This was the 1/6 Queen’s sector and although Captain Richard Rutherford and D Company quickly dealt with this initial incursion, enemy attempts to cross continued into the night.3 Nevertheless, despite the level of the river dropping some four feet – partly due to the fine weather and partly the result of closing the sluice gates at Valenciennes – the advantage was still with the men of the 1/6 Queens who ‘dominated the open ground on its front’.

Concerned by the strength of the German incursion Brigadier John Utterson-Kelso, commanding 131 Brigade, now involved the 2/Buffs Reserve Company to reinforce the 1/6 Queen’s. This movement of Captain Francis Crozier’s B Company completely unbalanced the defensive jigsaw that had been created by the battalions of 131 Brigade and allowed the German assault to penetrate the Queen’s line. This error of judgement ultimately opened up the western bank of the Escaut and effectively sealed the fate of the 44th Division. The Buffs were already under attack from German infantry who, under the cover of a heavy mortar and artillery bombardment, had crossed the river at the point where the wooded area surrounding Scheltekant Château met the river bank. Attacking the forward positions of A Company, which was pushed back to the ridge of high ground behind the reserve trenches, the enemy were soon in occupation of the Buffs’ positions in Huiwede and Petegem, ground which may well have been held had Crozier’s B Company not been elsewhere! There is certainly evidence of confusion and inexperience hampering operations at this stage. Lieutenant Robert Hodgins, the 131 Brigade Intelligence Officer, wrote that ‘no plan was established or received from division necessitating continual reference’ to the senior staff officer ‘for help and guidance’. What was more worrying was the opinion of Gregory Blaxland who felt his company commander had no views on how his company should be deployed in battle.

Hodgins also felt that the German use of the MP 38 machine pistol in close-quarter fighting tactics had taken the British by surprise, a factor that may have adversely impacted on the British troops who had little or no experience of automatic small-arms fire. That said, the British reply came quickly, in the shape of a section from the 1/5 Queen’s Carrier Platoon with orders to clear up isolated pockets of enemy troops. After a somewhat wild and inconclusive exchange with the enemy the carriers returned just in time to join Major Lord Edward Sysonby’s carrier attack on Petegem from the west. Advancing with two sections through the village Sysonby found the village burning fiercely but apart from the ‘main street being a shambles of dead men and animals’ no Germans were seen until Sysonby’s carriers turned left at the crossroads. At this point they came face to face with a column of marching Germans. Opening fire on the enemy with their Bren guns, Sysonby remembers one German firing an anti-tank rifle at him:

‘I shot him in the face with my revolver which was a very fluky shot as we were travelling at about 20mph. We then proceeded on our course for about a mile and a half into the enemy’s lines shooting all and sundry we saw.’4

The return trip was not without drama. Corporal Arthur Peters was hit and his carrier was knocked out leaving him with a shattered thigh. Temporarily taken prisoner he and two others were rescued by Sergeant Reginald Wynn under heavy fire. Wynn was awarded the DCM and Sysonby, who was the godson of King George VII, received the DSO. Sadly, Peters died of his wounds five days later.5 Following the carrier attack two companies of the 1/5 Queen’s did manage to establish themselves east of Petegem which returned control of the so-called Petegem gap – between themselves and the château at Scheltekant – to the British, who could now bring flanking fire to bear on any attempted enemy advance. But it was a situation that was not to last.

A little to the southwest of Petegem, 16 Platoon and the Buffs’ headquarters staff were still grimly defending the Scheldekant Château grounds as the 1/ RWK launched another counter-attack towards Petegem from Eekhout. Hopes of closing the gap were dashed when they were brought to a standstill on the railway line. For a few hours there was stalemate before the German gunners turned their bombardment on the 1/5 Queen’s still clinging to ground east of Petegem. Inevitably the hapless defenders were pushed back to new positions behind the railway line and the waiting German infantry flooded through the gap.

Enemy infantry quickly outflanked the Buffs and turned their attentions to the 1/6 Queen’s who rapidly became engaged by an enemy that appeared to have them almost surrounded:

‘The enemy could be seen to be working round the left and rear of B Company. Kwaadestraat Château grounds were badly shelled by guns in the rear, presumably our own, and small parties of enemy penetrated the grounds, but were driven out by a counter-attack by members of Battalion Headquarters. The recaptured posts were occupied by C Company, 1/5 Queen’s, which had just arrived as a reinforcement. About 8.00pm the Germans reached Elsegem and were firing into the flank and rear of the Kwaadestraat Château grounds. At the same time news arrived that the enemy was also across the Escaut on the right of the 1/6 Queen’s front, and this appeared to be confirmed by a display of white Very lights to the north and west of Eekhout ... Firing was now continuous; several fresh parties of the enemy had again got a foothold in the Château grounds and no more reserves were left to deal with them, so at 9.15pm Lieut-Colonel Hughes decided to extricate the remainder of the battalion before the position was completely surrounded.’6

As night fell the remnants of 131 Brigade fought their way back over the railway line, where they met units of 2/Royal Sussex who had been brought forward to fill the gap. 131 Brigade reformed north of Courtrai late on 22 May where the 1/5 numbered 22 officers and 447 other ranks while the 1/6 were reorganised into three companies. Of the reported 400 other rank casualties in the 1/6, over 130 were taken prisoner but, like their sister battalion, the number of wounded remained imprecise. Amongst those captured was Sergeant Alex Horwood who was serving with B Company 1/6 Queen’s. Horwood’s escape from captivity and subsequent evacuation from Dunkirk (see Chapter 15) was emblazoned over the front pages of the popular press and resulted in the award of the DCM.

Meanwhile at Oudenaarde the enemy incursions on the front of 2/Buffs had put pressure on the 4/RWK headquarters at Kasteelwijk Château and although well defended by Major Marcus Keane, two companies were overrun before the order to withdraw was given. Keane, along with two companies of 5/RWK had been ordered to cover the flank of the battalion as it broke contact with the enemy at 8.00pm on 21 May. Sergeant Jezard, the MT Transport Sergeant, was at Kasteelwijk Château when the order to withdraw was relayed to all ranks:

‘First of all we loaded all the casualties into a carrier ... having got them safely on board PSM Chapman said, “well boys here we go”, and we made our way to the main gate. We reached the gate and decided the best way out would be round the back and through the grounds and fields. We had not gone far when someone asked, “who can drive a truck?” Everyone looked round and then I saw a 15cwt beneath a tree. It had been plastered all day along one side with shrapnel – one rear tyre had been ripped open but this didn’t worry us.’7

Jezard’s account of the fighting around the château differs slightly from that of Lieutenant Colonel Chitty who reported that ‘the men fought to the end and twenty signallers, the officer’s mess cooks and drivers were among the casualties.’ Clearly some managed to escape as Jezard says there were 20 men in his party including Sergeant Humphrey, the Cook Sergeant, and PSM Arthur Chapman, commanding 5 Platoon, who was later singled out for the award of the DCM. Whether some fought on to the end is uncertain but we do know Marcus Keane was killed while commanding the rearguard.8

Major General Dudley Johnson was already the recipient of the DSO and bar and the MC when he was awarded the VC whilst in command of the 2/Royal Sussex in November 1918. Appointed to command the 4th Division in 1938 he was responsible for a six mile sector of the Escaut on the right of the 44th Division, a sector that included the Kerkhove bridge. Dug in around the bridge was A Company of the 1/East Surrey Regiment which occupied the village and was in touch with B Company on the left along the river bank. Across the river at Berchem C and D Companies with the battalion’s carriers were tasked with preventing enemy patrols from reaching the bridge. Overlooking the Surreys’ position was Mont de l’Enclus, a high point from which enemy artillery observers had an uninterrupted view. Lieutenant Colonel Reginald Boxshall later remarked that it ‘gave the German gunners, good observation, and we were heavily and accurately shelled’.

Working alongside 11 Brigade were the sappers of 7/Field Company who, in addition to preparing the bridge at Kerkhove for demolition, were also fortifying the riverside buildings. Second Lieutenant Curtis was at the bridge:

‘Road blocks had been erected east of the bridge and a light screen of the Surreys were ready to hold back the Germans if they appeared. Assault boats were issued to the Surreys so they could return across the river after the bridge was blown. Shortly after 23.00hours [11.00pm] on May 19, the Adjutant of 3 Div rearguard arrived to say the rear-most battalion was some miles away, and that the bridge should not be blown until it had crossed. It was now a question of waiting to see who would arrive first, 3 Div or the enemy.’9

Lieutenant Colonel Boxshall had no doubt that he gave the order that delayed the blowing of the bridge and writes that it was a battalion of Sherwood Foresters that were the last to cross the river before the order was given for its destruction.10 At what point Boxshall brought C and D Companies back is not clear but ‘eventually’, he wrote, ‘the Germans occupied all the east bank of the River Escaut.’

The battle at the bridge continued for most of the day as the Germans tried to cross the river under a curtain of heavy shellfire. The Regimental Aid Post (RAP) received a direct hit killing or wounding everyone who was working there; fortunately Lieutenant Donald Bird, the battalion medical officer, was dealing with casualties elsewhere at the time. Boxshall observed with some alarm that all the battalion’s anti-tank guns were also knocked out. On the Surreys’ right flank the 2/Lancashire Fusiliers were also under a heavy artillery and mortar bombardment. Major Lawrence Manly, noting the remarkable, accuracy of the blizzard of fire, noted that ‘Battalion Headquarters, A Company and B Company suffered the most’. Yet, despite the bombardment the East Surreys and Lancashire Fusiliers were managing to hold their own, a state of affairs that was not replicated on the left flank as Lieutenant Colonel Bill Green’s 5/ Northamptons came under increasing pressure.

The 42-year-old Green was a decorated RFC flying ace in the First World War and credited with nine victories between January and September 1918. Transferring to the Northamptonshire Regiment in 1921 he assumed command of the battalion in 1938. Now, with D Company in touch with the Queen’s on the left, the battalion was strung out along 2,000 yards of the Escaut. Although Boxshall makes no mention of this in his account, A Company of the Northamptons under the command of Captain Hart were dug in along the eastern edge of Berchem and it was there that the battalion had their first contact with the enemy:

‘A Company were well hidden in scattered houses on the edge of the village ... At about 11.00am a group of about twelve apparent refugees approached. To Captain Hart it seemed that they were walking with a somewhat martial stride and his suspicions were confirmed when they were followed by about twenty cyclists, riding in pairs, and a lorry. The section covering the road held their fire until the cyclists were a good target at close range and opened fire with Bren and rifles.’11

The first burst of fire took down the majority of the cyclists prompting the marching ‘refugees’ to break for cover and return fire. As the attack became more determined the company were withdrawn across the river by boat. Hart was given an immediate award of the MC and Privates Sharpe and Herbert the MM.

The bombardment that was causing havoc at Kerkhove was also being directed at the Northamptons and after some very fierce fighting the Germans managed to establish themselves in a small orchard on D Company’s front. Although they were discouraged from widening their foothold by a Northamptonshire bayonet charge, D Company sustained heavy casualties reducing the effective strength to less than two platoons. Brought into the fight as support, C Company lost around a third of its strength before the battalion front was readjusted and it was only the arrival of the 6/Black Watch during the night that prevented the enemy from working found the flank and surrounding the battalion.

Early on 22 May patrols from A Company established the Germans were now across the river in some strength and it wasn’t long before they directed their attentions towards Captain John Johnson’s C Company positions. After Johnson was killed by a direct hit, the company – by now very much reduced in numbers – got away only after Green ordered up the carrier platoon to hold the enemy, an order that resulted in five of the carriers being destroyed and eleven of its twenty-eight men being killed. Surrounded and out of ammunition, the remaining men of the carrier platoon fought their way clear with grenades. The orders to withdraw came not a moment too soon. The battalion had suffered enormously and, with eleven officers killed or wounded and C Company less than forty strong, the remaining rifle companies could only muster some sixty-five men apiece. Worse still was the news that Lieutenant Colonel Green had been killed at Teighen.12

Back on the 1/East Surrey’s front at Kerkhove the Germans had also got across the river and with the battalion’s left flank turned it looked very much as if the situation was fast becoming untenable; a situation that did not prevent Captain Ricketts from leading a counter-attack with C Company:

‘It all started with a sergeant arriving at my position very much out of breath and with a revolver in his hand to tell me A Company were surrounded and they needed the reserve company to get them out ... I went in deployed in Y formation. The only opposition met on our way came from a house and a party of apparent Fifth Columnists which we despatched, with me on the Bren and PSM Bob Gibson bowling a couple of Mills bombs. I eventually arrived at A Company’s position and found Captain Finch White who told me he was intact, but was receiving a belting and could do with some help.’13

Ricketts was wounded along with Second Lieutenant Meredith in the attack which, in the event, turned out not to be needed – it was later in the day that A Company would have appreciated Rickett’s assistance! Shortly after the C Company counter-attack the brigade major arrived at battalion headquarters with orders to withdraw immediately. Boxshall recalled that he was unhappy with the order as it meant ‘moving men over open ground exposed to full view from enemy observation points. However, as both flank battalions were on the move I had no choice. I issued orders by runner (all lines had been cut), and backed them up with liaison officers in carriers. Three companies got the orders, but A Company on the right did not.’14

Pinned down by enemy fire and finding themselves isolated and outflanked, Captain Finch White realised the Germans were now across the river on both flanks and waited until dark to find out for himself what was taking place:

‘After going a short distance I was fired upon from what had been the position of Battalion Headquarters and it was clear we had to get out quickly ...We withdrew with the Germans advancing parallel to us on each flank. Fortunately they took no notice of us. We did come under heavy machine-gun fire from our own rearguard, not the Surreys, and had to take cover ... We then got a lift in some transport and rejoined the battalion.’15

The Surreys’ withdrawal was not without cost. Machine gunned by low flying aircraft as they retired out of the Escaut valley, Boxshall’s carrier was hit by anti-tank tracer which penetrated the vehicle, badly bruising him and wounding his second-in-command, Major Ken Lawton.

It was a similar story on the sector held by the Lancashire Fusiliers. At 3.00pm on 22 May news that the right flank had given way prompted Lieutenant Colonel Leslie Rougier to push Captain Hugh Woollatt’s carrier platoon into play to form a defensive flank. Last seen at B Company Headquarters, Woollatt was taken prisoner shortly before the orders to retire to the Gort line were received, a move that cost the 44-year-old Rougier his life when he was killed by shellfire near the railway cutting south of the Tiegham Ridge. Command was assumed by Lawrence Manly who brought the battalion out of action with over 175 officers and men either killed wounded or missing.16

At Avelgem Lieutenant Colonel James Birch commanding the 2/Bedfordshire and Hertfordshires had established his headquarters in a small café close to the main cross roads. Deploying C Company at Escanaffles on the eastern bank of the river with orders that the bridge was not to fall into enemy hands, the remaining companies – presumably under orders from Brigadier Evelyn Barker commanding 10 Brigade – were directed to positions on the forward edge of Mont de l’Enclus. In his account Birch writes that he met Barker and Major General Johnston on Mont de l’Enclus and was immediately told to move his men to the east and south faces of the hill, leaving him to wonder just how he was going to hold the position with so few men. However, sanity appears to have prevailed as the orders were changed yet again resulting in the battalion taking up new positions on the western bank of the river.

Nevertheless there was still a sticky moment or two before C Company was finally brought back across the bridge:

‘Eventually the last section under the command of Lance Corporal Major came doubling back over the bridge followed at a distance by the head of a column of refugees. The sapper sergeant called upon the civilians to go back but they paid no heed. He then told the troops to run flat out and he would press the plunger in a minute. Lance Corporal Major and his section then completed an Olympic 100 metre dash when there was a deafening roar as one and a half tons of explosive charge erupted and bits and pieces of the bridge were thrown high in the sky.’17

Lieutenant Colonel Birch’s account is quite critical of the ‘marching and counter-marching’ his battalion had been subjected to on 19 May, writing that, ‘I have no doubt that there was good reason for it, but I did regret that I had no opportunity of making a good recce of the canal bank on such a vast front before the enemy arrived.’ Birch neglects to mention that the flat and featureless ground between the river and Avelgem gave his forward platoons little cover from German artillery and mortar fire.

As they had done further north, German troops made their first appearance on the far bank on the morning of 20 May. Birch’s unease at the extent to which the battalion’s positions were overlooked was not improved by the first casualties at the hands of enemy snipers lodged in the industrial buildings at Escanaffles. At 11.00am 12 Platoon was subjected to a heavy mortar attack, during which PSM Warren was badly wounded, adding to Birch’s overall apprehension as to the vulnerability of his canal side defences. In reality he was between a rock and a hard place. If he remained where he was the battalion would continue to take heavy casualties but if he withdrew to a safer line German infantry would be given the opportunity of crossing the river and establishing themselves on the western bank:

‘The very exposed positions on the edge of the canal could not be held and I was much concerned. I moved some carriers to increase the fire power in this area and that night fresh positions were dug. I had made a thorough reconnaissance of our side of the ‘billiard table’ and with the brigadier decided to make our main defence along the courant about 1,000 yards back from the canal with the forward platoons still close to the canal.’18

All troops were in their new positions by dawn on 21 May and it was not long before German troops – as expected – began filtering over the blown bridge.

The British reply was a counter-attack launched by one platoon of C Company supported by artillery. The plan involved Second Lieutenant David Muirhead and 15 Platoon approaching the enemy from a flank and, with support from 13 Platoon and the guns of 22/Field Regiment, checking the German incursion. Second Lieutenant Robin Medley witnessed the attack:

‘The guns fired bang on time and the ground around the target area erupted with explosions, but as yet the attacking troops could not be seen as they were hidden from view. After some eight minutes the attacking platoon came into view with the soldiers advancing steadily, rifles and bayonets across their chests ... it was a splendid sight and, as far as could be seen there were no gaps in the lines. Meanwhile, the artillery was pounding the objective and 13 Platoon was firing onto the enemy bank of the canal with their Brens. Bang on time the assault charged as the guns lifted ... giving 15 Platoon time to deploy and firm up its objective. After sixteen minutes the guns stopped firing and there was a sudden silence.’19

Birch is more matter-of-fact than Medley in his account and simply tells us the enemy ‘cleared off when they saw the attack was on’ but Muirhead’s counter-attack clearly had the desired effect and the battalion was not bothered by German infantry again during its short occupation of the canal.

The orders to withdraw arrived later that night and with the carrier platoon forming the rearguard the Beds and Herts began their move west at 9.00pm under cover of darkness. Quite why the 4th Division withdrawal from the Escaut was begun in daylight is anyone’s guess. Blaxland suggests it may have been connected to the intensity of the shelling but it was that very shelling that killed two commanding officers and accounted for further significant losses, losses that Birch’s battalion appeared to avoid.

North of Pecq Hugh Taylor and the 1/Suffolks had taken up their positions along the line of the river on 20 May. As we know, much of the 1st and 3rd Divisional sector was overlooked by the prominence of Mont St Aubert on the eastern side of the river, a feature that had not gone unnoticed by Lieutenant Colonel Lionel Bootle-Wilbraham commanding the 2/Coldstream Guards. An early indication that the German gunners were using the hill for artillery observation was confirmed when the Suffolks’ commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel Eric Frazer, was wounded by shellfire along with Captain John Trelawney during their initial reconnaissance of the river. Once in position on the river line Taylor confessed to being a little surprised at the close proximity of the enemy across the water:

‘Now that we were in the forward area we could see the enemy’s line, he was occupying a row of houses to our front and we could see very easily where he was ... The range was too great for our weapons [to be used with effect but] through field glasses we could see DRs [Dispatch Riders], runners and all kinds of people moving about. They were very rash as they lit fires in certain houses. We could see the snipers crawling through the long grass towards us on the other side of the river, so I told our company commander and he sent for one of ours, and I think he was successful as we did not see the German snipers again.’20

Fortunately the Suffolks got away from the Escaut on 22 May relatively unscathed, but it proved to be a different story a little further south. The 3/ Grenadier Guards were deployed south of Pecq with three companies on the river bank and one in reserve. To their left, in the village of Pecq itself, were the 2/Coldstream Guards with the 2/Hampshires in reserve a mile to the west at Estaimbourg. Lionel Bootle-Wilbraham arrived in the early afternoon of 19 May, noting the sappers were already preparing the bridge for demolition. Deploying 1 and 3 Companies along the river he kept 2 Company in reserve with the roads leading into the village covered by 4 Company.

Apart from the blowing of the Pecq bridge at 2.00am on 20 May there was very little enemy activity to interfere with the Grenadiers’ preparations for the arrival of the German 31st Infantry Division. The first contact came on the 1 Company front with the death of Captain Evelyn Boscawen who was sniped during the night from the opposite bank where an unseen enemy was mustering for a major attack the following morning. It came shortly before dawn: a sudden and violent assault – undoubtedly being directed from Mont St Aubert – which succeeded in establishing a bridgehead at the boundary between the two Guards battalions.

The first Bootle-Wilbraham heard of the enemy incursion was around midday. After a rapid reorganization of the defences around battalion headquarters at the château on the N510 Lille road, Captain Charles Fane was ordered to take his carriers up to the rising ground on the right of 1 Company to form a defensive flank. He was killed shortly afterwards by shellfire:

‘In the meantime a gun had opened fire to our right rear and shells from it were landing 150 yards north of Battalion Headquarters. I could not help wondering whether the Germans had not succeeded in getting an infantry gun across the river and were working their way up between the Grenadiers and ourselves to Estaimbourg. Bunty Stewart-Brown went forward to take command of 1 and 2 Companies and the carrier platoon. Sometime later he reported the Pecq-Pont-a-Chin road was held and there did not appear to be any enemy between the road and the canal ... For five minutes the road to the château was searched by a battery of medium guns. There was one direct hit amongst pioneers and a number of men were killed and wounded, the latter including CQMS Burnett. One of the signallers, a very young boy, burst into tears, not so much from fright as because two of his pals had been killed and he was splattered with their blood. That was the climax of the battle. From then on things improved.’21

Meanwhile on the Grenadiers’ front, Guardsman Les Drinkwater of 4 Company was in a large barn which was screened from enemy observation by the riverside vegetation. Drinkwater’s company was at the critical junction of the two Guards battalions, a position which was giving Major Reggie Alston-Roberts-West, commanding the company, some anxious moments. Sending Drinkwater and Sergeant Bullock – presumably to report on the situation on the left flank – the two men found themselves in the thick of the fighting with enemy infantry from IR 12 forming the German spearhead and establishing themselves in the wood on the ridge of high ground known today as Poplar Ridge:

‘When we arrived we realised the enemy was determined to wipe out this flank. We were lying down behind a bush, bullets were cracking over our bodies, trench mortar bombs and shrapnel shells were exploding. The din was terrible. To our amazement, through all this noise, we could hear the familiar sound of a Bren gun firing as if it was defying the whole German Army.’22

It may not have been the whole German Army but if the account of Hauptmann Lothar Ambrosius – commanding the IR 12 assault – is correct, the Guards were inflicting a considerable number of casualties on his infantry attempting to cross the river. Ambrosius reporting nearly 200 casualties inflicted on his men by the Guards with some 66 killed in the action.23 Drinkwater writes that his admiration for the two men firing the Bren gun was shattered by a direct hit which blew Guardsman Arthur Rice ‘clean through the bush’ and badly wounded Guardsman George Button who was firing the Bren. Dragging a blinded Button by the hand and shouting for Drinkwater to follow him, Bullock was last seen ‘running like blazes’. Despite Rice pleading to be left, Drinkwater remained with the badly wounded guardsman convinced he would soon become a prisoner. But fortune was smiling that day and they both eventually arrived back at the barn where Rice was loaded onto one of the two company trucks:

‘We were very fortunate, the large double doors faced the bank – the enemy were closing in from the rear. A decision had been made for the first truck to turn left, the other right. On clearing the barn we ran straight into the enemy – the essence of surprise was with us. At this stage the enemy dared not fire in case they hit each other; we were through, a hail of bullets hit our truck wounding the driver, but we continued and were soon over a ridge of high ground and out of sight of the enemy.’24

Les Drinkwater may have escaped captivity but the venom of the German advance was still threatening the left flank, giving Major Allan Adair little choice but to counter-attack with his reserve company. At 11.30am Captain Lewis Starkey’s 3 Company, supported by three carriers led by Lieutenant Reynall-Pack, advanced towards the German positions now established at the base of Poplar Ridge. ‘It was’, wrote Allan Adair, ‘a magnificent and inspiring sight to see the company dash forward through the cornfield and vanish out of sight over the ridge.’ Suicidal was the word that immediately sprang to Guardsman Bill Lewcock’s mind as he and his comrades advanced across the cornfield in open formation. Met with a hail of machine-gun fire 3 Company was soon taking significant casualties which included Captain Robert Abel-Smith the second-in-command.. Lewcock saw Lieutenant the Duke of Northumberland go down at the head of his platoon and recalled the attack was in great danger of stalling in the face of mounting casualties:

‘At this stage the attack would probably not have been successful had it not been for the action of two individual Grenadiers. The first was Lieutenant [Heber] Reynell-Pack, in command of the carrier platoon, who took his carriers across the bullet-swept ground, using them as though they were tanks, and silenced the machine guns on the left by hurling grenades into the midst of the crews: he was killed in his carrier immediately afterwards. The second was L/Cpl [Harry] Nicholls.’25

Harry Nicholls was on the right of the 3 Company advance; having already been wounded in the arm by shrapnel he seized the initiative as the company suffered mounting casualties and became bogged down. Running forward with a Bren gun and firing from the hip he silenced three enemy machine-gun posts, during which time he was again wounded in the head. Moving forward he continued to bring fire to bear on the Germans until his ammunition ran out.

Guardsman Percy Nash was with Nicholls as he dashed forward, he remembered feeding Nicholls with ammunition for the Bren gun as they advanced in short rushes towards the enemy. After silencing the machine gun posts at Poplar Ridge, Nash says Nicholls then began firing on the enemy who were crossing the river and sunk at least two boats before their ammunition ran out. Nash was Mentioned in Despatches and promoted to Sergeant while Nicholls – on Nash’s evidence – was reported as missing believed killed and his ‘posthumous’ VC was subsequently received by his wife Connie. It was only after the presentation at Buckingham Palace that it was learnt Nicholls was a prisoner and in hospital in Germany and he was finally presented with his cross at Buckingham Palace in June 1945.

But the fight here was not entirely a Guards affair. The counter attack was supported by A Company of the 2/North Staffordshires under the command of 41-year-old Major Frederick Matthews, who was ordered to attack with two platoons and the battalion’s carriers in the direction of Esquelmes – a plan which failed to manifest itself fully but did in the event prevent any German advance penetrating beyond the main N50 road. Sadly Matthews was killed during the attack and although his body was not recovered at the time, he was later found during the battlefield clear-up.26

The counter attack – which had accounted for some 60 Germans killed and over 130 wounded – forced the IR 12 bridgehead from the west bank of the river and restored some semblance of calm to the battlefield. Understandably the greater number of casualties suffered in the fighting were in the ranks of the 3/Grenadier Guards where twenty men were taken prisoner and six officers and fifty-one other ranks were either killed in action, missing or died of wounds. Amongst the wounded, Arthur Rice was safely evacuated along with Les Drinkwater who was hit by shellfire after arriving at the RAP with Rice. Both men survived the war. The Coldstream suffered two officers and twenty men killed or missing while the 2/North Staffs lost six officers and men from A Company. It was during the course of this battle that Bootle-Wilbraham remembered, with some irony, receiving an order of the day from the Commander-in-Chief, ‘in which he said the British Army had to withdraw through no fault of its own and was to now stand and fight on the line of the [Escaut]’.

Lieutenant General Barker’s deployment of I Corps along the Escaut appeared to bear out the poor opinon of him held by some of his subordinates – the 3rd Division’s commander, Major General Bernard Montgomery, amongst them. Alan Brooke later confided in his diary that Barker ‘cannot make up his mind on any points ... and changes his mind shortly afterwards’. During the withdrawal from the River Dendre Barker’s three divisions had retreated along one road, communication between brigade and division was almost non-existent and delayed messages were contradicted by new orders that themselves were often rescinded as British and French units became inextricably muddled. So chaotic was the situation on the roads that Private Ben Duncan was moved to remark, with more than a hint of sarcasm, that the ‘modern French Army did a great deal to add to the general confusion with horse-drawn kitchens and guns.’ Little wonder then there were misunderstandings as to who was to be deployed where. Certainly inadequate staff work was largely responsible for the 2nd Division being squeezed in between the the 42nd and 48th Divisions with the unfortunate 6 Brigade originally ordered to hold the river line between Chercq and Calonne. On arrival they found units of 126 Brigade from the 42nd Division already in possession of part of the sector, resulting in 126 Brigade remaining and the 6th moving into reserve at Willemeau. As Bell remarked in his History of the Manchester Regiment, it was, ‘quite impossible to trace all the consequences of the orders and counter-orders that were issued to the three brigades’ [of 2nd Division] on 20 May.

But it was in the I Corps sector that another VC was awarded south of Tournai, where the 2/Norfolks, under the command of Major Nicholas Charlton, had positioned three companies along the river frontage at Chercq. Charlton had only been in command since 18 May after Gerald de Wilton had been evacuated following a mental breakdown. But at least the Norfolks and 1/8 Lancashire Fusiliers had arrived in time to relieve 6 Brigade before the German assault began, a scenario that was unfortunately not repeated further south at Calonne.

Deployed on the right of the Norfolks’ sector – with some of his platoon positions in the grounds of the Château de Chartreaux – Captain Peter Barclay – who had been awarded the MC for his patrol work on the Maginot Line – had established the remainder of his men in the cover of buildings along the river. Private Ernie Leggett remembered his section was concealed extremely well amongst the ruins of an old cement factory. It was from these hidden positions that Barclay and his men observed German infantry making a determined effort to cross the water by laying wooden hurdles across the rubble of the demolished bridge:

‘I reckoned we’d wait until there were as many as we could contend with on our side of the canal before opening fire. There were SS with black helmets and they started to come across and were standing about in little groups waiting. When we’d enough, about 25, I blew my hunting horn. Then of course all the soldiers opened fire with consummate accuracy and disposed of all the enemy personnel on our side of the canal and also the ones on the bank at the far side – which brought the hostile proceedings to an abrupt halt.’27

The accuracy of the resulting artillery and mortar fire indicated to Barclay that the German gunners had guessed correctly as to their positions and were now using their superior fire power as a prelude to a more determined attempt to cross the river. This same bombardment was also searching the battalion’s rear areas; a lucky round succeeded in hitting battalion HQ, wounding Charlton and his adjutant thus placing the battalion in the hands of Major Lisle Ryder. It was around this time that Barclay was wounded in the stomach and thigh and with no stretcher available he insisted on being tied to a door and carried by four stretcher bearers to deal with what he described as ‘a very threatening situation’.

Barclay had spotted German infantry crossing the river on the company’s right flank but in spite of his rising number of casualties he hit back with the meagre reserves available to him – the company clerk, radio operator and other personnel from company headquarters – led by Sergeant Major George Gristock with orders to cover the flank and deal with a German machine gun that had established itself ‘not very far off ’ on Barclay’s right. His plan hinted at more than a touch of desperation and, of course, he had no idea it would result in the award of a VC, but it worked:

‘He [Gristock] placed some of his men in position to curtail the activities of the post so effectively that they wiped them out. While this was going on fire came from another German post on our side of the canal. Gristock spotted where this was and he left two men to give him covering fire. He went forward with a Tommy gun and grenades to dispose of this party which was in position behind a pile of stones on the bank of the canal itself. When he was about 20–30 yards from this position, which hadn’t seen him, he was spotted by another machine-gun post on the enemy’s side. They opened fire on him and raked him through – smashed both knees. In spite of this he dragged himself till he was within grenade lobbing range, then lay on his side and lobbed the grenade over the pile of stones [and] belted the three Germans.’28

The arrival of B Company secured the right flank and Barclay and Gristock were evacuated to the RAP. The Norfolks’ war diary makes no mention of Gristock’s action or his award of the VC which was announced – along with that of Richard Annand – in the London Gazette of 23 August – sadly after Gristock’s death. Sharing a corner of the RAP with George Gristock was Ernie Leggett who had been badly wounded in the cement factory by enemy mortar fire. Initially left for dead he was rescued by ‘Lance Corporal John Woodrow and a chap named “Bunt” Bloxham’. Fortunately all three men were evacuated well before the orders were received on 22 May to retire to the Gort Line. Gristock and Leggett would meet again in the Royal County Hospital in Brighton where Leggett was horrified to learn the CSM had had both legs amputated at the hip. ‘I used to stay with him for half an hour or an hour. Every day they’d wheel me through. Then that horrible morning came on 16 June when they hadn’t come and got me.’29

Some of the most desperate fighting along the Escaut was on the 48th Divisional front south of Tournai where Major General ‘Bulgy’ Thorne – a former Grenadier Guards officer who had fought with the 1st Battalion at Gheluvelt during the First Battle of Ypres in 1914 – must have despaired at the indecisiveness displayed by General Barker and his staff as they struggled to deploy I Corps. There is no doubt that the delay in relieving the territorial battalions of 143 Brigade resulted in disastrous consequences for the 8/Warwicks who were still on the Escaut long after Douglas Money and the 1/Royal Scots had arrived to take over the 1/7 Warwicks’ positions on the night of 20 May.

The 1/7 Warwicks, under Lieutenant Colonel Gerard Mole’s command, were a little to the north of Calonne holding a front of some 1,000 yards with two companies deployed in buildings along the river and two in reserve on the sloping ground to the west. The 8th Battalion was in and to the south of Calonne and held a slightly longer frontage, again amongst buildings along the river side. Lieutenant Colonel Reginald Baker moved three companies forward, keeping D Company in reserve at battalion headquarters at Warnaffles Farm. The regular 2nd Battalion from 144 Brigade was at Hollain where Captain Dick Tomes thought the battalion’s position on the river was too open on the right flank and provided the enemy with a ‘covered approach’ on the left:

‘We had sunk some barges the day before but the stream [Escaut] was not wide, only some 30 yards. The ground was flat by the river and the slope on which the town of Hollain stood, which did in fact overlook the far bank in a few places, was not adaptable to defence on account of the houses; we could not have stopped the crossing of the river from it.’30

Although there had been desultory firing the previous day, the fighting increased in intensity during the morning of 20 May. At Hollain German infantry from the 253rd Division began crossing in the afternoon under the cover of intense shelling, making their most determined effort opposite D Company where a sharp bend in the river offered more concealment – exactly the point where Tomes had anticipated the enemy might give them trouble. Tomes’ account tells us this was largely thwarted, although ‘a few men with LMGs had succeeded in gaining a foothold on our side and were shooting from gardens in front of A Company’. By the time darkness fell the battalion was still holding its positions.

On the 1/7 Battalion front a number of men had been killed or wounded by enemy shellfire before the relief by the 1/Royal Scots went ahead as planned, although the shelling did give Harold Money some anxious moments before the battalion were established at midnight. However, the intended relief of the 8/ Warwicks by the 2/Dorsets never took place, much to the chagrin of the men from the ‘Heart of England’. All the evidence points towards the confusion of ‘orders and counter-orders’ which had dogged the Dorsets on 20 May, so much so that by early next morning the battalion was still east of St Maur attempting to extricate itself from the seemingly Gordian knot of units from 4 Brigade which were ‘milling around in the early morning mist’.

In the meantime the 8/Warwicks were having a hard time of it due to German mortars and machine guns; one casualty being the battalion medical officer, Captain Neil Robinson who was killed whilst loading wounded into an ambulance. Battalion headquarters and the B Echelon transport also came under fire but the forward companies did manage to prevent the enemy from crossing the river after dark – or so they thought. At midnight a C Company patrol was fired upon from a building on the west bank: evidently units of IR 54 had managed to gain a foothold. Darkness also meant that any relief that might have been planned could not now take place until the following night. Lieutenant Colonel Baker’s men resigned themselves to yet another day of hard fighting.

The 21 May was, in the words of the Royal Scots Adjutant, Major James Bruce, ‘a hellish day! We were mortared and shelled heavily.’ The German lodgement on the 8/Warwicks’ front held by C Company was also proving troublesome but not as troublesome as the pressure now being brought to bear on B Company on the battalion’s left flank. Under cover of a high explosive bombardment some German soldiers managed to get across but the bayonets of the Royal Scots dispatched them quickly. However, despite the efforts of their neighbours, the Warwicks’ forward companies were slowly pushed back into an enclave on the edge of Calonne, giving further opportunity to the infantry of IR 54 to cross at the junction of A and B Companies. The situation now hung in the balance. The surviving Warwicks were all but cut off from battalion headquarters and were in great danger of envelopment. Decisive action was needed and needed quickly.

Lieutenant Colonel Baker’s next course of action was undoubtedly decisive but whether his decision to lead the attack himself was altogether wise is open to debate. Instead of bringing his reserve company into the fight, he assembled an assaulting force from battalion headquarters and led them forward into the teeth of the German menace, now firmly established on the west bank in some strength. Captain Neil Holdich, commanding C Company of the 1/7 Warwicks felt the whole exercise to be several hours too late:

‘Now followed one of the most fantastic affairs since the Light Brigade, albeit on a much smaller scale. Their CO removed his helmet and equipment, put on his orange and blue regimental forage cap, took up his swagger stick and formed up the men of his Battalion HQ in one extended arrowhead on the open ground behind Calonne. Himself at ‘point’, and supported by a couple of Bren gun carriers, the whole show moved like part of a peacetime Tattoo towards the village. As they descended the slope into the village, the carriers’ guns ceased to bear on the enemy and, unhindered, the Germans blazed away. It was all over very quickly, a crash of flame and smoke and all went, three officers and 50 men, only two surviving.’31

The attack was a disaster. Baker was killed along with the majority of his men, leaving the British dead strewn across the battlefield and only two survivors to return to Warnaffles Farm. Undoubtedly courageous but ultimately foolhardy, Baker’s attack had made very little difference to the situation apart from depriving the battalion of its commanding officer.

The 1/Cameron Highlanders’ counter-attack later in the morning did manage to partially re-establish the line which certainly eased the lot of the Royal Scots. Captain Ronald Leah commanding B Company recalled being ‘shelled all the way between Merlin and the main road’ over ground that was unpleasantly exposed. From Leah’s account it would appear that his company headquarters was for a short time situated in the wooded area around the Château de Lannoy and the B Company platoons formed up on either side of the Rue de L’Aire. With their objective being the small bridge near the cement works, Leah’s men managed to clear the broken ground behind the works – although he says the area was a ‘death trap’ with 12 Platoon losing a lot of men. The attack hit Leah’s company very hard and he was particularly saddened by the death of Lieutenant Peter Grant, his second-in-command. Yet it may well have been the Cameron Highlanders’ counter attack – together with the dogged resistance elsewhere – that finally saw the Germans being pulled back over the canal that night, a retirement that allowed the surviving 8/Warwicks to begin their own withdrawal. Although more rejoined later, that evening at roll call only 366 men answered their names.

On the 2/Warwicks’ front 21 May opened with another determined attack on D Company’s positions resulting on enemy troops gaining what Dick Tomes termed as ‘a considerable footing on our side of the river’. Shortly after this, a runner arrived at battalion headquarters with the news that Major Phillip Morley had been killed leading an attack on a German machine-gun post – leaving 21-year-old Second Lieutenant Kenneth Hope-Jones in command of the company. The attack on D Company was renewed just after midday and although they held on to their positions, enemy troops managed to get into the small wood immediately behind them. Relief arrived in the form of a counter attack by three companies of the 1/Ox and Bucks:

‘The plan entailed B Company advancing 15 minutes ahead of the remaining companies to secure the right flank of the attack, a difficult task which was carried out at some cost, including another very good young officer, Second Lieutenant [George] Duncan. The carriers supported the attack from the west while the 3-inch mortars fired a hundred bombs into the wood.’32

As far as Dick Tomes was concerned the attack came at just the right moment:

‘With the assistance of A Company’s covering fire [they] drove the enemy back a considerable distance – though not over the river – and captured about a dozen prisoners. But D Company suffered heavily and the remaining two subalterns, Hope-Jones and Goodliffe, [Goodliffe was later found to have survived] and a great many men had been killed. PSM Perkins was wounded and later died together with the majority of his platoon taken prisoner. No officers and 30 men remained out of two platoons.’33

The situation around Calonne and Tournai still remained tense despite the numerous counter-attacks which appeared to contain enemy incursions. But the constant pressure and superior firepower from an enemy intent on crossing the river was taking its toll. The enemy footholds gained along the Escaut – however small – were disturbing enough but the breakthrough on the 44th Division front at Oudenaarde had compromised the whole of the Escaut line leaving Gort and his commanders in an unenviable situation. As with the BEF units further north, instructions ordering the withdrawal arrived on 22 May and set in motion the retirement from the I Corps sector which was ‘successfully carried out’, wrote Harold Money, ‘to the accompaniment of mortars, shells and last, but not least, the song of the nightingales singing as though to drown out the former’. Nevertheless, the Royal Scots had suffered heavily, losing over 150 men, one of which was Major George Byam-Shaw who had been frozen to his Bren gun five months previously on the Maginot line.

The decision to abandon the Escaut was confirmed at the GHQ conference at Brooke’s headquarters at Wambrechies on the late afternoon of 21 May which, according to Brooke, was marked by Gort’s rather gloomy account of the situation facing the BEF. The Arras counter-stroke – dealt with in the next chapter – had failed, the Germans were reported to be close to Boulogne and there were enormous difficulties in the resupply of ammunition to the fighting divisions. ‘We decided’, wrote Brooke, ‘that we should have to come back to the line of the frontier defences tomorrow evening. Namely to occupy the defences we spent the winter preparing.’ Brooke’s diary does not mention if the possibility of a British evacuation from the channel ports was discussed at this meeting but I find it hard to accept that it was not: surely Gort and his commanders must have been aware that the chances of the BEF remaining on the French mainland were receding with every hour that passed.34