Chapter Ten

Hazebrouck and Cassel

24–29 May 1940

‘Often the enemy came near to gaining a foothold, as when a party of them infiltrated through the woods almost into the heart of our sector and were only checked by the prompt action of CSM Bailey who collected a small party of clerks, signallers, cooks, anyone he could find, loaded them with as many grenades as they could carry and led them in a hectic bombing counter-attack which utterly routed the enemy.’

Lieutenant Michael Duncan, 4/Ox and Bucks, at Cassel on

28 May 1940.

We last heard of 145 Brigade on 17 May at Hal, covering the retreat of the 2nd Division. It was a day that the Territorials of the 1/Buckinghamshire Battalion of the Ox and Bucks Light Infantry remembered vividly as their commanding officer, 46-year-old Lieutenant Colonel Alexander Burnett-Brown, collapsed from exhaustion and command was handed down to Major Brian Heyworth. A Cambridge graduate, Heyworth moved from Manchester in 1936 after his appointment as a barrister in the Treasury Solicitor’s Department in London, a move that took him to Beaconsfield and a transfer to the Ox and Bucks Light Infantry Depot at Newbury.

On 24 May 145 Brigade, under the command of Brigadier Nigel Somerset, were in billets at Nomain, southeast of Lille and had been warned that their move to Calais was imminent. Captain Hugh Saunders commanding D Company of 1/Bucks was delighted by this news declaring that a ‘restful task such as the strengthening of the garrison of Calais’ would be most welcome after ‘the buffeting of the last ten days’. Completely unaware of what was unfolding at Calais, Heyworth’s battalion spent all day waiting for orders, which finally arrived at 9.30pm along with the transport. Few of the slumbering men of 145 Brigade would have had any idea that the destination on the route card had been changed from Calais to Cassel or that at Bailleul, the Buckinghamshires’ destination had changed again to Hazebrouck. The fast moving pace of events now focused the minds of the British commanders on keeping the corridor to Dunkirk open and 145 Brigade was about to play its part.

Somerset’s orders on 24 May were refreshingly straightforward: Hazebrouck, Cassel, Wormhout and Bergues were now part of the outer perimeter around Dunkirk and were to be held at all costs and 145 Brigade was to move immediately to secure Hazebrouck and Cassel. An element of fate dictated the move of the Buckinghamshires to Hazebrouck, one which rested on the movement order which placed the battalion at the rear of the brigade column that left Nomain. As the convoy travelled up the D933 it was a simple matter to divert Heyworth’s men to Hazebrouck while the remainder of the brigade continued to Cassel.

Hazebrouck had been a hive of activity since Gort and Pownall had arrived on the afternoon of 22 May with the intention of moving their command post and reuniting GHQ in the town – a move that was swiftly reversed when news of the enemy incursions on the Canal Line dictated a rapid relocation, leaving a handful of staff to follow on. Saunders tells us that on arrival in the town the battalion was greeted by a Captain Alistair Campbell who was commanding the Hazebrouck garrison:

‘Campbell explained that GHQ troops, supplemented by various small detachments of troops lost from their units, at present occupied the town and owing to a penetration by enemy AFVs [armoured fighting vehicles] in an easterly direction over the canal running through St Omer it had been decided that Hazebrouck was to be held at all costs.’1

The action involving Sergeant James Mordin and the 392/Battery gun had taken place the day before and, although enemy tanks had reluctantly withdrawn in compliance with Hitler’s Halt Order, the town had been severely bombed on several occasions resulting in the majority of the inhabitants leaving. Thus it was a largely deserted town that greeted Heyworth’s initial reconnaissance – apart from the Luftwaffe who regularly machine-gunned the streets. Realizing the town was too large an area to defend Heyworth – hoping the railway lines would form an anti-tank barrier – deployed his companies to hold the town south of the Calais-Bailleul railway and west of the railway line running south to Isbergues; an entirely sensible decision but even then there were several undefended gaps between company positions which ultimately allowed German units to infiltrate between them.

Heyworth had some difficulty in establishing with any accuracy exactly how many troops he was to command. Extracting an approximate list from Campbell along with a map of the town, he appeared to have inherited a contingent of leave men from the 6/York and Lancaster Regiment, a collection of orderlies, signallers and drivers from the former GHQ and a platoon of 4/Cheshires with four Vickers guns. The guns of 223/Battery were added to by one platoon from 145/Brigade Anti-Tank Company armed with 25mm Hotchkiss guns under Sergeant Ken Trussell and a composite battery of 98/Field Regiment based at Le Souverain farm southeast of the town. It is unlikely that Heyworth could have held out at Hazebrouck as long as he did without the support of 98/Field Regiment which, early on in the battle, established an observation post in the Hazebrouck church tower to direct the battery’s fire.

Heyworth established his battalion headquarters in the centre of town in the Foundation Warein Orphanage on the Rue de la Sous-Préfecture. A Company and Captain Dick Stevens were placed in reserve and occupied the former GHQ building across the road. As groups of stragglers drifted into town Heyworth directed them to A Company which by nightfall on the 26th had been reinforced by nearly 200 men. The three remaining Buckinghamshire companies were distributed around the perimeter with B Company on the right, C Company astride the D916 and D Company covering the western approaches.

Lieutenant Trevor Gibbens, the medical officer attached to the battalion, found the orphanage cellar a convenient location in which to set up the RAP and spent most of 26 May collecting medical supplies from any doctors’ houses he could find in the town. Fortunately ambulances were still able to come and go without enemy interference as were individuals from other units seeking medical treatment. One of these was a gunner officer from 98/Field Regiment:

‘A Jeep came roaring up the road and stopped. An officer beside the driver got out and said in the most conversational tone “I seem to have got one in the elbow, doc”. I cut off his sleeve and realized that his elbow joint had been completely shot away, with a gap of an inch or two between the bones. The radial artery and tissues in the limb were intact, so I put a long wire splint on the whole arm and sent him off in one of the last ambulances.’2

The individual in question was Captain Lord Cowdray who had been hit northeast of Steenbecque by a burst of machine-gun fire which had also killed Gunner Ronald Scoates who was driving the vehicle and wounded one of the two signallers in the back. Cowdray later had his arm amputated but was successfully evacuated from Dunkirk thanks to Gibbens.

The battle for Hazebrouck began on a wet and misty Monday 27 May when tanks from the 8th Panzer Division overran the 2/Royal Sussex positions south of the town. One of the first units in action was D Company which was overwhelmed by tanks from Oberst Neumann-Silkow’s Panzer Kampfgruppe in the Bois des Huit Rues. Shortly after this the battle opened in Hugh Saunders’ sector when his attention was drawn to a German vehicle near the level crossing on the western edge of his sector. Calling in artillery support from a nearby 25-pounder of 223/ Battery – which missed its target, allowing a German reconnaissance group to escape – it wasn’t long before the tanks arrived:

‘We had not been back in our Company HQ for more than a quarter of an hour before three light tanks appeared and swooped down on the 25-pounder, smashing the gun and wounding all its crew save one. The crew retreated through one of 17 Platoon’s outposts, hotly pursued by two tanks which fired a salvo straight into the weapon pits, before they turned and made their way off.’3

Saunders was relieved to discover there were no casualties from 17 Platoon but the ease with which enemy tanks had penetrated the perimeter left no one in any doubt of what was to come. At 10.00am Saunders received a message from Second Lieutenant Tom Garside commanding 18 Platoon that a large force of enemy armoured vehicles was approaching from the direction of St Omer, a message confirmed ten minutes later by the observation post on the Wallon-Cappel road. Saunders had a distinct feeling they were ‘for it’:

‘While we were waiting, for some obscure and still incomprehensible reason, the battalion water truck arrived to fill up eight water bottles which I had reported were empty. The arrival was unhappily the signal for the commencement of the attack and, hardly had [the truck] stopped outside the gate than an enemy tank rushed up from the area of Les Cinq Rues and, with a carefully aimed shot, hit the water cart straight in the [water] tank ... The [German] tank in question was one of three that were circling round 17 Platoon’s position, harassing them as much as possible and trying to unnerve the defenders. They were hotly engaged by 17 Platoon’s anti-tank rifles, and after one of them was hit, they withdrew.’4

The Bucks were certainly ‘for it’. By 11.00am all three companies were engaged as enemy tanks probed their defences and German artillery and mortars bombarded their positions, making life very difficult for Lieutenant John Palmer in his observation post in the church tower and eventually forcing him to beat a hasty retreat.

But this was only the beginning. Half an hour later a runner from 16 Platoon announced that infantry were being brought up along the St Omer road in strength and although they had already been engaged by Corporal Wade and his section from 17 Platoon, and temporarily scattered by the battalion’s single 3-inch mortar, D Company’s supremacy over the enemy was short lived. Within minutes a steady machine-gun fire made it almost impossible for anyone to lift their heads. But, as Saunders reflected later, it looked as if the attack was developing on the C Company front. It was. While D Company were coming under heavy fire, 30-year-old Captain Rupert Barry and his platoons of C Company were fending off an attack by five enemy tanks with their Boys rifles. It was a desperate fight and despite putting most of the tanks out of action, 14 Platoon was overrun and another – possibly Lieutenant Geoffrey Rowe’s 13 Platoon – was cut off and surrounded by the afternoon. Responding to Barry’s SOS, Heyworth ordered A Company to establish a fresh line in the buildings behind C Company in order for Barry and his men to withdraw. Very few of A Company reached the new line and Barry – one of only two regular officers in the battalion – was captured later that evening.

On the eastern edge of the perimeter, Lieutenant Clive Le Neve Foster’s 11 Platoon of B Company did not have to wait long before it too became engaged by German infantry advancing down the railway line. Beating off the initial attack the company held their ground under enemy machine-gun fire and occasional sniping which appeared to be directed from buildings to the north of the railway. Foster remembered that later that day an anti-tank officer arrived at their positions with news that the Germans were in the north of the town and asking for help in retrieving an anti-tank gun which was ‘on the wrong side’ of the railway line:

‘There was very heavy machine-gun fire down the railway and six sets of rails to get it over. I took the sergeant major and about 8 others for the job and we ran over and all crossed safely. We got hold of the gun and it was a heavy affair to move. We then drove a 15cwt lorry over and after some difficulty hitched it up and got safely back again. I can well remember watching the machine-gun tracer bullets streaking down the line.’5

Back across the railway line Foster found the company had withdrawn and large numbers of German infantry were approaching the town. Quite where the company had gone is not clear but the company commander, Captain John Kaye, was amongst those who made it back to England. Saunders and his men were also conscious that enemy forces were pouring into the town and they were powerless to stop them:

‘By about 7.00pm the enemy were well inside the town and we could hear the sound of firing in the streets. In several places fires had broken out from incendiary shells and clouds of smoke filled the air, but Battalion HQ was still intact. I decided to make contact, if I possibly could, and Pte Page volunteered to make his way to Battalion HQ. He had only, however, to put his foot outside the gap in the wall which we used as a door to bring a veritable hail of tracer bullets down on him. After several attempts we realized it was hopeless to get out of the building by daylight, as all our lines of departure were covered by machine guns.’6

At battalion headquarters the 27-year-old Gibbens was struggling desperately with the wounded as the upper floors of the orphanage were being bombarded by mortars and tank shells. From below floor level they could hear the crack and rumble of masonry as battle raged above:

‘Bit by bit the wounded were brought down ... There was clearly not going to be much opportunity to get the wounded away for some days ... I did the rounds in quiet moments, gave plenty of morphia and sips of water ... one man was brought down with his abdomen completely opened up and his bowels pouring out. There seemed to be nothing to do but put wet, warm packs on him and fill him up with morphia. He died quietly the next day.’7

Unbeknown to Gibbens, enemy forces were closing on battalion headquarters from three sides, having cut off and surrounded the rifle companies whose resistance had been reduced to platoon-sized pockets. By the time darkness had descended over a burning Hazebrouck the battalion had been practically destroyed. It appears that in the confusion of battle, withdrawal orders were not received by the men in isolated company positions and those that did receive them were given no point of reference to withdraw to.

At 8.30pm the Germans completely broke through the D and C Company positions and pushed on towards the centre of town. Saunders took it upon himself to order the surviving men of his company to get way, feeling that in the circumstances Major Heyworth would have acted in a similar fashion. Foster, who was cut off from B Company, lay up behind the railway embankment with two others until dark when all three managed to evade capture and get to Dunkirk. As to how many of the battalion escaped captivity is uncertain but Ian Watson is of the opinion that up to half of the battalion may have escaped, particularly those from the outlying rifle companies.8

It was a different story for the men still holding out at battalion headquarters. Private Perkins, one of the D Company runners, was one of a number of men who had drifted back to the orphanage where he was ordered to take up a defensive position:

‘At two points in the building were Bren guns covering two streets and one more covering the big yard at the back of the building ... Myself along with the other HQ personnel took up our positions with our rifles at every available window there was ... for the first hour or two it was more or less a sniper’s job, as I had quite a few crack shots at motor cyclists who kept crossing quite frequently at the top [of the road]. The building was now getting in a bad way, one part of it had already collapsed, as at this stage we were handicapped by our anti-tank rifles having been put out of action so it was left to our Bren guns to try and stop the tanks. It was hopeless and heartbreaking for the Bren gunners, their bullets just bounced off, but undaunted they kept on.’9

The war diary, which was completed by Saunders shortly after he had returned to England, describes the fighting coming to an end around 9.30pm on 27 May. Certainly by nightfall all contact had been lost with the rifle companies and battalion headquarters was surrounded. In a final effort to make contact with any troops still holding on Heyworth sent out two patrols: one to find the B Echelon transport and the other to B Company. Second Lieutenant Martin Preston got as far as the town square before he was killed while Second Lieutenant David Stebbings, the Intelligence Officer, finding the B Company positions deserted, managed to return with the news. Only then was it fully realized at battalion headquarters that ‘it and HQ Company were the only parts of the battalion available and capable of fighting another day’.

As soon as it was light on 28 May enemy mortars ranged in on the convent hitting an unloaded ammunition lorry which added to the noise of battle by a series of continuous explosions for almost two hours. At 1.00pm a number of tanks came past the front of the building firing at almost point blank range at the beleaguered garrison which replied with rifle, anti-tank rifle and Bren gun fire, the intensity of which was reduced somewhat by the GHQ troops’ unfamiliarity with the workings of the Lee Enfield rifle! That the end was near must have been obvious to all concerned but still they held on.

The Ox and Bucks War Chronicle gives the time of Major Heyworth’s death as 4.30pm. He was crossing the Rue de la Sous-Préfecture to the former GHQ Headquarters when he was hit by a sniper’s bullet. It was an imperfect end to a gallant individual’s short life. There is some evidence to suggest Heyworth and his second-in-command, Major Elliott Viney disagreed about surrendering, Heyworth being determined to defend the building to the last man as he had been ordered. But with Heyworth’s death command devolved to Viney who soon afterwards evacuated the building with the hundred or so men who were still able to fight, taking up position in the small, walled orphanage garden. It was around this time that the adjutant, 32-year-old Captain James Ritchie was killed attempting to leave the building by another entrance. Trevor Gibbens’ account provides a glimpse of the final minutes before the building collapsed:

‘The school was virtually being razed to the ground it seemed. The noise of falling floors got louder. I remember hearing that the part of a house which is last to collapse is the doorways. I think it is certainly true. Anyway I stood in the doorway between cellars three and four. Number four led to the stairs to the front door. Soon after the roof came in, covering all the fifty or so wounded on stretchers on the floor with rubble. I imagined they would all be killed and as I walked to the doorway, I remember a voice under the rubble saying “get off my face”.’10

Trapped and with virtually no ammunition, Viney’s men waited patiently in the orphanage garden, determined to make their break for freedom under the cover of darkness. It never happened. Spotted by a German patrol Viney had little choice but to surrender the remaining garrison. The defence of Hazebrouck was over.

A little over 5 miles to the northwest of Hazebrouck is the small and ancient town of Cassel, built on top of a significant hill which rises nearly 600 feet and dominates the surrounding countryside. Before May 1940 it was probably more associated with Frederick Duke of York who is supposed to have marched his ten thousand men up and down the hill during the Flanders campaign of 1793. During the 1914–18 war the town had remained firmly behind Allied lines and hosted the headquarters of General Ferdinand Foch; but recent German bombing and marauding tanks spotted in the area now undermined any historical security the town may have enjoyed.

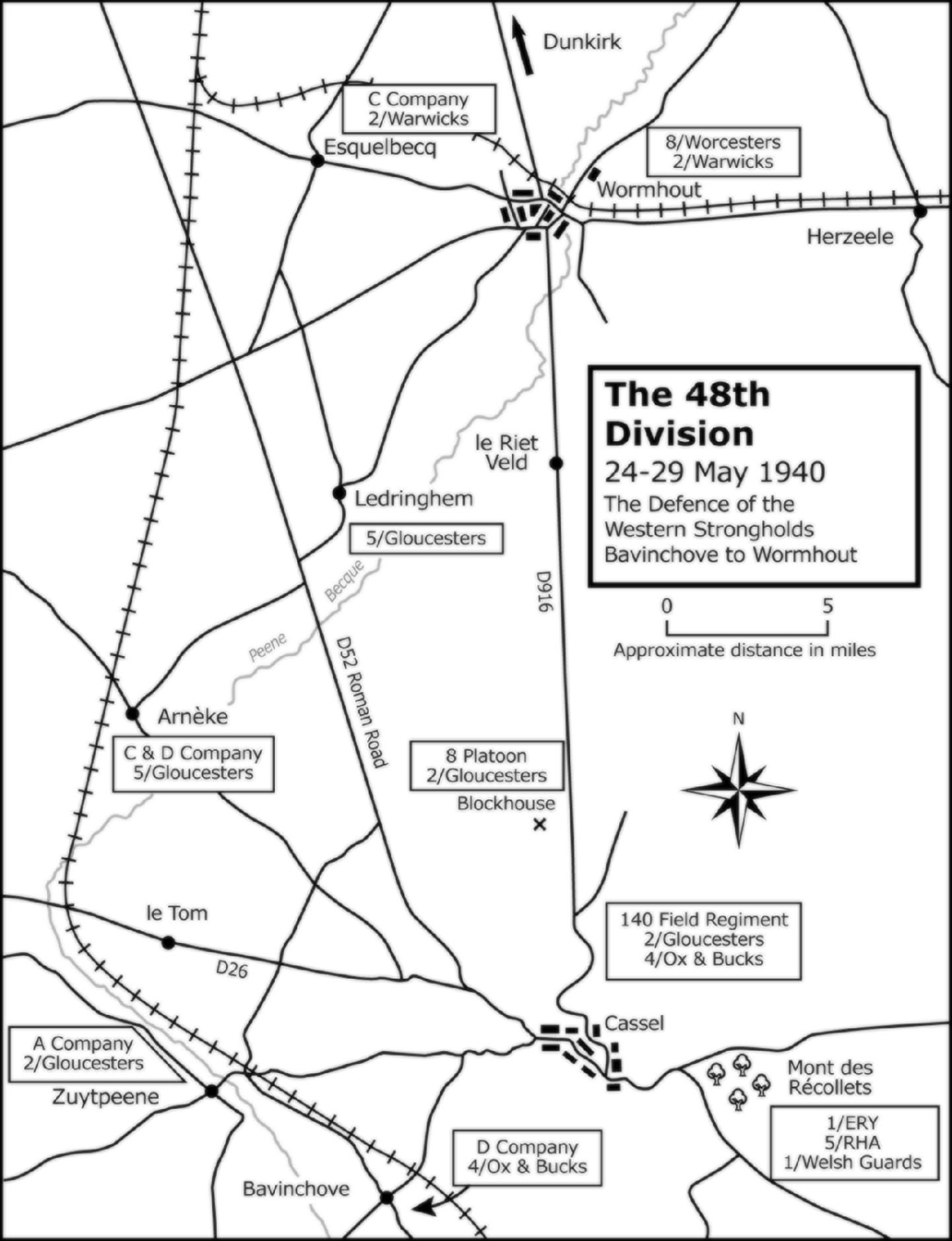

With its unique view across the flat Flanders plain, the town sits on a vital road junction with Dunkirk 25 miles immediately to the north and Lille to the south-east. Half a mile to the east of Cassel is the wooded Mont des Récollets standing some 60 feet lower. It was a place that Corporal Moore and B Squadron of the East Riding Yeomanry remembered as cold, wet and continually under fire. With Ledringhem about 4 miles to the north-west and Bavinchove to the south-west, Cassel had become one of the lynchpins protecting the western face of the Dunkirk Corridor.

The trucks carrying Lieutenant Michael Duncan and the men of A Company, 4/Ox and Bucks from Lille had lost their way five times during the night, an experience which Duncan found somewhat unnerving as he ‘had no idea where the enemy were and any deviation from the route might well land us amongst them’. Duncan’s opinion was undoubtedly shared by Major Maurice Gilmore, commanding 2/Gloucesters, who observed, with his usual clipped tone that ‘the battalion reached Cassel after a journey of some vicissitude in the early morning of Saturday, 25 May’.

From the moment 145 Brigade was redirected to Cassel it was referred to as ‘SomerForce’ by GHQ. Whether or not Brigadier Somerset approved of this term is not recorded but as the various units headed towards the hilltop town Somerset was very much aware he was now commanding a mixed force of regular soldiers from the 2/Gloucesters under Gilmore’s command, and Territorials in the shape of the 4/Ox and Bucks, a battalion which had only recently welcomed Lieutenant Colonel Geoffrey Kennedy as their new commanding officer. The two infantry battalions were supported by two troops from 5/Royal Horse Artillery (RHA), the 367/Battery guns from 140/Field Regiment, two batteries of 53 (Worcestershire Yeomany) Anti-Tank Regiment and some machine gunners from the 4/Cheshires. There were also a smattering of Royal Engineers from 226/ Field Company, Royal Signals and RAMC personnel which Second Lieutenant Tom Carmichael of the East Riding Yeomanry rather dismissively called ‘the odds and sods.’

The East Riding Yeomanry (ERY) had been in France since February 1940, moving into Belgium on 14 May with the 1/Fife and Forfar Yeomanry which made up the 1/Armoured Light Reconnaissance Brigade. Arriving at Cassel on 24 May, the regiment was equipped with Mark VIb light tanks and carriers and made a welcome addition to Brigadier Somerset’s 145 Brigade. Sharing the ERY’s occupation of Mont de Récollets were the two RHA troops of 18-pounders – D Troop taking the west side and B Troop the east – and the Welsh Guards who had recently been defending Arras.

Captain Eric Jones, the Gloucesters’ adjutant, recalls driving up the hill towards the town with Major Gilmore and meeting Kennedy of 4/Ox and Bucks about halfway up: ‘The two COs discussed the situation and as brigade HQ had not yet arrived, decided, by mutual agreement, to divide Cassel for defence.’ This gentleman’s agreement divided the defence of Cassel into two halves with the Ox and Bucks holding the eastern half of the perimeter and the Gloucesters the western half. Keeping A Company in reserve, Gilmore established battalion headquarters in what is now the Banque du Nord on the southern edge of the Place du Général Vandamme deploying B Company under Captain Bill Wilson facing north and west and linking up with C Company of the Ox and Bucks Two of Wilson’s platoons occupied the houses on the north side of the road on the edge of town immediately before the ‘S’ bends on the D 52 and faced open country with 10 Platoon and 27-year-old Second Lieutenant George Weightman occupying the isolated farm – called Weightman’s Farm in Eric Jones’ account – 400 yards down the hill to the north.11 D Company and the Mortar Platoon under Captain Anthony Cholmondeley were in the centre facing west overlooking a wooded area sandwiched between the present day D11 and the D933 with their headquarters in a huge pigeon loft in the grounds of a large house. C Company and Captain Esmond Lynn-Allen faced south and southwest and linked up with A Company of the Ox and Bucks.

Lieutenant Colonel Kennedy took over the large red brick Gendarmerie on the Rue des Berques as his battalion headquarters, a building he shared with Lieutenant Colonel Douglas Thompson who commanded the 1/ERY. Kennedy kept B Company in reserve and deployed D Company to cover the Steenvoorde road from Mont de Récollets while A and C Companies took up position along the eastern perimeter. The anti-tank defence was coordinated by 33-year-old Major Ronnie Cartland of 53/Anti-Tank Regiment who sited all his 2-pounders to cover the main approaches.

The Reverend David Wild probably took the same approach road into Cassel as Eric Jones and Major Gilmore had which he described as a long climb following a series of zig-zags up the steep face of the hill. Where the road takes a sharp right-angled bend by the cemetery he was stopped short by the carnage that lay before him:

‘Some Belgian horse-drawn artillery had taken a direct hit at this point, and all over the road were the remains of wagons, guns, horses and men. A hundred yards farther up the street was a burnt out six-wheeled petrol lorry, and several of the houses, including Haig’s old GHQ, were just empty shells.’12

Returning later, Wild buried the bodies of the dead in the cemetery and had the horses dragged away, noting that thereafter all the troops in the town referred to the corner as Dead Horse Corner.

To Michael Duncan it was obvious that if the Germans attacked between the various fortified points along the corridor there was little to stop them, the only hope was that the enemy would be delayed by strongly fortified and tank-proof localities. The defence of Cassel was a much better prospect than that of Hazebrouck and to that end the troops settled down to digging and fortifying the town in their allotted company areas. However, it was almost inevitable that these initial dispositions were to change in what Gilmore called ‘tactical rearrangements’:

‘The first of these alterations was the sending out of 8 Platoon under 2/Lt R W Cresswell to occupy a partially completed blockhouse about two and a half miles out of Cassel on the road to Dunkirk. The second was the sending out of the rest of A Company to occupy the village of Zuytpeene, on the railway line west of the town. [D Company] of the 4/Ox and Bucks was similarly sent out to occupy Bavinchove, also on the railway, south by a mile or two, of Zuytpeene. These three forward positions were to break up any enemy onslaught before reaching the main position.’13

As D Company moved out to Bavinchove their place was taken up by B Squadron ERY, who, like the infantry, were digging new positions until well after dark. ‘Tempers were not improved’ by this additional digging, remarked Duncan, nor were they soothed by the slice of fried meat loaf and cup of tea which masqueraded under the name of dinner.

Second Lieutenant Roy Cresswell and 8 Platoon moved north to the blockhouse during the evening of 26 May to find the structure still incomplete and occupied by refugees who he says were persuaded to leave. Early the next morning the platoon worked hard to block up the entrances and remove the builder’s hut and scaffolding before the enemy attack that Cresswell was expecting later that day:

‘At 6.00pm the Germans were seen advancing in open order across the western skyline. The side entrance was immediately shut and a heavy fire brought to bear on the advancing enemy, upon which several casualties must have been inflicted at a range of 600 yards. Between 7.00pm and 8.00pm a furious attack was launched against us, which was beaten off, the only lasting effect being that one nearby haystack was fired by tracer. This proved to be advantageous to us, since it burnt all night, and the light this caused made the work of the look-outs slightly easier. In the attack the Germans used a type of shell which was about 2-inches long and which burst inside the blockhouse. Part of one of these hit L/Cpl Ruddy, who was severely wounded in the head and throat.’14

Tuesday May 28 was relatively quiet for Cresswell and his men, no enemy attacks took place although mechanized columns were seen moving east of Cassell, leading to much speculation as to what was happening to the battalion in the hill. Everything changed the next morning, a day which Cresswell described as ‘one of the worst days we had experienced in the blockhouse.’ It began at about 9.00am with the appearance of Captain Derick Lorraine, a wounded British artillery officer, who was seen hobbling on a crutch shouting ‘wounded British officer here’. Already a POW, Lorraine had been turned out of an ambulance by his captors. Forced to approach the blockhouse at gunpoint, Lorraine made every effort to indicate there were Germans on the roof attempting to start a fire with petrol in the well of the unfinished turret housing. Cresswell remembered that he responded immediately and that Lorraine replied ‘do not reply’ in a lower voice:

‘When he reached the east side he looked down at a dead German and said out loud, “There are many English and Germans like that round here.” At the same time he looked up at the roof of the blockhouse, an action which seemed to indicate German presence on the roof. With that he hobbled out of sight.’15

Lorraine’s silent gesturing was not lost on Creswell. As smoke filled the blockhouse the defending Gloucesters donned gas masks while they struggled to put out the fire, Cresswell remarking that they had failed again to drive them out but in the process had improved the warmth inside the blockhouse.

Their battle came to an end on 30 May, heavy weapons were brought up and their continued resistance seemed futile, particularly as nothing had been heard from Cassel. They had held the blockhouse for three days keeping the smoke from the fire at bay by the use of an old quilt damped with water from the blockhouse well and demonstrated a grit and determination worthy of their famous cap badge. As Cresswell and his platoon were being marched away the fire continued to burn for the next week as a constant reminder of a tenacious defence.

At Zuytpeene Major Bill Percy-Hardman and A Company came under attack at 8.00am on 27 May from a strong force of tanks and infantry which surrounded the garrison and cut off all communication with Cassel. Fighting continued all day with individual sections gradually withdrawing on to company headquarters situated in the centre of the village. Orders to withdraw were sent from Cassel at 12.15pm but the dispatch rider returned having failed to get through to them. Sent out again he returned a second time only to find his way blocked again by enemy forces. However, at 7.00pm Privates Tickner and Bennet arrived at battalion headquarters in what was described by Jones as ‘an exhausted and hysterical state’ having left Percy-Hardman some three and a half hours earlier:

‘They had volunteered to bring a message to Bn HQ after previous runners had been killed. When they left the company, it was surrounded and under heavy mortar fire. There had been many casualties. The last thing they had seen was a mortar shell land upon the house in which company HQ was situated (in the cellar). They had passed through the enemy line along a drain and by ditches and had great difficulty in entering our own lines. Both were convinced that Major Percy-Hardman was killed.’16

In actual fact Percy-Hardman was still very much alive but his company had been reduced to a handful of survivors and one Bren gun which allowed them to fight off one final attack before they surrendered. Both Percy-Hardman and Cresswell were later awarded the MC.

One mile east of Zuytpeene D Company of the 4/Ox and Bucks were coming under attack at Bavinchove. Commanded by Captain Charles Clutsom, they had been sent to hold the east side of the village but it wasn’t until early on 27 May that they came into contact with the enemy. From their vantage point above the Rue des Ramparts at Cassel, Michael Duncan and Captain Lord ‘Pat’ Rathcreedan were able to watch the approach of an armoured column:

‘As Pat, the Company Commander, and I stood watching for signs of the enemy we saw, winding out along the road from St Omer to Bavinchove, a long column of enemy tanks preceded by motor cyclists and armoured cars and followed by infantry in half tracks ... suddenly the head of the column broke, as if splintered, with pieces flying in every direction as they came under fire from the defenders of Bavinchove. For a while there was a lull, as if orders were being given and then, methodically, inexorably, the encircling movement began.’17

Second Lieutenant David Wallis, an officer attached to the Brigade Anti-Tank Company, does not say if he was present at Bavinchove but does confirm that D Company were attacked by motorcycle troops, troops in lorries and about six light tanks:

‘The front section of D Company were attacked first on its flanks, the enemy stalking it. Grenades were thrown by both sides. At about 9.30am when the section withdrew across the line to its rear platoon, it found the enemy were on its right flank and pushing round behind the whole company. At this time the wounded were sent back in the transport and narrowly escaped capture. The rest of the company withdrew across the fields.’18

With the battle around Cassel beginning in earnest the gun crews found no shortage of targets and, as was the case at Hazebrouck, it is doubtful the garrison could have held out for so long without the fifteen 2-pounders of the Worcestershire Yeomanry and the 18-pounders of 367/Battery. There were however, limitations. Captain Eric Jones recalled his frustration at being told the 18-pounders were unable to elevate sufficiently to hit targets below the hill, he also remarks that companies ‘repeatedly asked for artillery support and even though targets were pinpointed on the map, the gunners were either not available or could not give any support’.

Nevertheless, the gunners inflicted heavy losses on enemy armour. Bombardier Harry Munn’s anti-tank gun was overlooking the D11 Gravelines road when he spotted twenty-four tanks heading towards him. Opening fire through a gap in the woods below, his crew were alarmed to see their shells bouncing off the lead tank:

‘By now the tank was less than 100 yards from our position and we still could not penetrate its armour. The only thing I could think of was that the wheels that propelled the tank tracks were unprotected and so I shouted to Frank ‘Hit the bastard in the tracks, Frank.’ The gun muzzle dipped slightly and just as the tank moved we fired hitting the track propulsion wheels and the tank halted abruptly swinging to one side. Still full of fight they turned their gun in our direction and fired again hitting the bank in front of the gun. Our next shell must have disabled the turret as they opened the escape hatch and ran for their lives back towards their lines. George Prosser our Troop Sergeant had left his Troop HQ when he saw we were about to engage the tanks and laid down by the gun taking pot shots with his rifle. He hit the last German to leave the tank, who fell down by the side of his tank. The other two tanks that came through with the one we had just stopped were on the right and left of our position. I decided to engage the one on the left as it was close to the outskirts of the town and firing mortars at a target in our lines. It was a perfect target silhouetted against a small hillock. I gave the necessary commands – direction – range – and a zero lead fire. Frank pressed the firing pedal and this time the shell penetrated the armour, exploded inside the tank and blew it into small pieces as its own ammunition went up. There were no survivors. The third tank had not moved from the point where we had first sighted it and its turret moved slowly round searching for our gun. I re-laid the gun on the new target, gave the order ‘Fire!’ Bill Vaux had already loaded and Frank followed the tank traversing left and right as it searched for our position. Frank talked to himself as he followed the target, ‘Keep still you bastard’ and as the tank paused for a second he fired, completely destroying this one as we had the previous one.’19

The Worcester gunners would account for some forty AFVs before the town was finally evacuated. On the Mont des Récollets the guns of B Troop RHA accounted for a number of tanks as well as responding to K Battery’s request in Hondeghem for supporting fire – an action we will look at more closely later. B Troop on the eastern side of the hill disabled at least two tanks before losing two guns to a Luftwaffe attack.

On the western edge of the town the Gloucesters’ D Company line was penetrated by an enemy tank on the first day of the battle and although destroyed, must have rung some alarm bells with the company commander, Anthony Cholmondley:

‘A very tricky situation arose when an enemy tank succeeded in getting into the grounds of the company [headquarters]. An attempt by a party from B Company, consisting of Captain Wilson, 2/Lt Fane, CSM Robinson and Private Palmer, to assist D Company by a flanking stalk, was nullified by a direct mortar bomb hit on their Boys rifle. Eventually the tank was set on fire by one of the anti-tank guns.’20

Private Palmer had actually hit the tank with one round from the Boys rifle before the mortar bomb exploded destroying the gun and wounding him in the back. Tragically the mortar round was from the Gloucesters’ own mortar platoon, which, although it discouraged any further activity from the German tank, left a shocked Lieutenant Julian Fane attempting to get a shell dressing on the hole in Palmer’s back before the medics arrived.

If the ground attack was not enough the constant bombardment from enemy artillery and aircraft caused mounting casualties which, in Michael Duncan’s opinion, made life quite difficult at times. However, what was noticed on the Ox and Bucks A Company front was the reluctance of German infantry to press home their attacks where their supporting armour failed to make headway. It had not gone unnoticed elsewhere along the perimeter and as the day wore on tank attacks were becoming perceptibly more cautious, often firing from hull-down positions in an attempt to get the infantry forward.21 That evening the scattered remains of enemy tanks were visible for all to see and as dusk settled over Cassel the evening rain at least helped extinguish some of the fires that were still burning furiously.

Yet, for all the enforced jollity which no doubt did much for morale, the end was inexoribly creeping up on the Cassel defenders. The Reverend David Wild was a little perturbed when German infantry managed to direct machine-gun fire onto Dead Horse Corner. ‘Bit by bit they seemed to be working themselves closer to the town’ noted Wild, forcing him to climb the grassy slope above the communal cemetery to make his way to the Gendarmerie. In the B Company sector pressure was increasing around 10 Platoon at Weightman’s Farm which, by 10.30pm on 29 May, was completely cut off. The previous day Captain Bill Wilson had been at the farm when several tanks approached the position, they were beaten off with anti-tank rounds but infantry were seen to be gathering about 400 yards away.

The farm had already received two direct hits from enemy shellfire and there had been several casualties, added to which came the disconcerting news that tanks were again reported crossing the road towards the farm. Shortly after this news arrived at the Gloucesters’ headquarters that a direct hit on the farm had killed George Weightman and left the survivors in disarray. With Corporal Christopher Waite and his section of 10 Platoon still grimly holding the position, the remainder were collected up by Bill Wilson:

‘Pulling the rather shaken 10 platoon together, I started to lead them back to their position. We had just got into the tiny yard at the back of HQ when a shell landed in the kitchen doorway. L/Cpl Badnell, one of my signallers was killed outright, dreadfully mutilated. About 10 others were badly injured. Private Phelps next to me had both legs blown off, save for tiny threads of muscle. I was for the third time amazingly lucky, receiving only a small piece of shrapnel in the thigh.’22

Later in the day the farm was abandoned with Wilson placing the survivors further up the hill in what had been the Cheshires’ machine-gun positions.

The attacks appeared to be focused initially on B and D Companies of the Gloucesters and during one of these a mortar shell hit an 18-pounder gun positioned near the B Company Headquarters, killing 21-year-old Second Lieutenant Gerald French, the battalion Intelligence Officer, who was on his way to liaise with the gunners. Later in the morning the attacks spread round the perimeter seeking a weak spot but none were successful in penetrating the defences at any point.

During the morning when the battle was at its height a badly shaken despatch rider arrived with orders to withdraw, an order which should have arrived the previous day. Apparently Captain John Vaughan serving with the 8/Worcesters had spoken to the DR ten miles to the north-east at Bambecque early on the 29 May, Vaughan says the DR was asking the way to Cassel after having got lost during the night. Whether this was because the DR was trying to avoid enemy patrols is unclear but Vaughan gave the man directions, which explains why the order did not reach Somerset until after 8.30am.

With Cassel surrounded the lateness of the message had effectively landed the whole garrison ‘in the bag’. Michael Duncan’s grim assessment of the situation did not hide his irritation:

‘It was already too late. Even had it been possible to break off the battle, which it was not, no attempt could be made to leave during the hours of daylight, and, by nightfall, all the enemy tank units had been heavily reinforced with infantry so that the chances of even getting out of Cassel were small whilst those of reaching Dunkirk were hardly worth a consideration.’23

Nevertheless, orders for the withdrawal were circulated and zero hour set for 9.30pm. The garrison assembled between Cassel and the Mont de Récollets and moved off towards Dunkirk in single file, the last unit to leave the stricken town being the ERY who had destroyed all their vehicles save the carriers. It is a matter of record now that the rearguard actions fought by the ERY were largely responsible for keeping a large German force occupied while 145 Brigade attempted to reach the coast. In June it was apparent that only 7 officers and 230 men of the regiment had got home, a large proportion of which were from the B Echelon detachment commanded by Second Lieutenant Edmund Scott who had left Cassel on 28 May.

The break-out was remarkably successful but, as one might expect, there were casualties. 24-year-old Second Lieutenant John Clerke Brown, commanding the Ox and Bucks Carrier Platoon clashed early on with enemy tanks and died of wounds a week later and Major James Graham, commanding C Company, was killed leading a bayonet charge at Winnezeele – the 38-year-old Graham was a former international athlete and cricketer. Captain Michael Fleming, whose father was killed in 1917 serving with the Oxfordshire Hussars, was mortally wounded near Watou and, like Clerke Brown, died of wounds in captivity. Amongst the many who were taken prisoner was Michael Duncan of whom we will hear more in Chapter 15.

The Dunkirk perimeter line was over ten miles to the north and by dawn few, if any, parties were more than halfway there. It was not long before most of the men were either caught in the open or rounded up after being surrounded by German units. Small groups did manage to evade capture and make it back to England but the majority were destined to spend the next five years in German POW camps.24