Chapter Twelve

Ledringhem, Wormhout and West Cappel

26 May–29 May1940

‘It is one thing to fight with proper equipment, but to fight and not run away without equipment is quite a different kettle of fish. The boys stood their ground – they were bombed, burnt out and sniped at and still they held. Who could ask for more?’

Corporal Eric Cole, HQ Company 1st Battalion Welsh Guards.

The 48th Division’s sector of the western face of the Dunkirk Corridor extended north from Cassel to the twin villages of Arnèke and Ledringhem and the larger town of Wormhout which lay a further two miles northeast on the D916. All three locations were held by Brigadier James ‘Hammy’ Hamilton’s 144 Brigade. Hamilton was highly regarded by many of the officers in the brigade and was described by Captain Bill Haywood as ‘fearless and imperturbable with a wonderful sense of timing and an uncanny anticipation of the enemy’s movements’. Over the next 48 hours he was going to need all these qualities.

Lieutenant Colonel Guy Buxton and the 5/Gloucesters moved into Ledringhem on 26 May with the same orders given to the 2nd Battalion at Cassel – to hold on at all costs. Buxton, a former officer in 4/Hussars, had to spread his five companies across a front of nearly 4 ½ miles to cover the village of Arnèke which lay across the D52 to the southwest. Establishing his headquarters in the Mairie at Ledringham with HQ Company close-by, Buxton deployed B Company in Ledringhem, C Company astride the D52 Roman road and A and D Companies – supported by five anti-tank guns from 53/Anti-Tank Regiment – slightly forward in Arnèke.

Buxton’s deployment of the Gloucesters was made in consultation with Hamilton’s overall strategy in which he assumed – correctly as it turned out – that Arnèke, being the most westerly point in his line, would be attacked first, thus allowing the two companies of Gloucesters deployed in the village to fall back onto Ledringhem before they were overwhelmed. In this manner Hamilton hoped to divert some of the enemy units heading towards Wormhout where he had placed the 2/Royal Warwicks and the 8/Worcesters.

Early on 27 May both villages came under attack from artillery and mortar fire and Arnèke was assaulted by tanks and infantry of the German 20th Division with the intention of crossing the railway line running between Noordpeene and Esquelbecq. Initially the German attack was held with the Carrier Platoon doing some excellent work in ambushing the assaulting troops. By the end of the day, however, the village had been practically surrounded and during the night both companies were brought in across the Roman road to Ledringhem leaving five enemy tanks and a number of armoured cars disabled. That night Ledringhem was subjected to a heavy artillery bombardment which inflicted considerable damage on the already shell scarred village. By midday on 28 May assault troops from IR 90 and IR 76 were making their presence felt, forcing Buxton to pull in his companies and prepare an all-round defence.

As the intensity of German air and mortar attacks increased, information brought in from the Gloucesters’ patrols added to battalion second-in-command Major F W Priestley’s unease that the enemy were working round the flanks of the village and cutting off their escape route to the north. Priestley’s suspicions were first raised when the telephone line to brigade HQ was severed and then by a later conversation with Private Albert Joines, who reported coming under fire from the north on four separate occasions while taking messages to and from brigade HQ at le Reit Veld on the D916. As Priestley said himself, ‘It was pretty evident that the village was surrounded.’

Apparently frustrated by the lack of progress against the Gloucesters’ dogged defence, IR 90 called upon the services of 3 Kompanie, 20/Pioneer Regiment which was equipped with Flammenwerfer 35 flamethrowers, a weapon already familiar to British and Commonwealth troops in the First World War:

‘During a second attack the enemy produced a flamethrower, the fuel of which did not ignite. He was disposed of, but not before much of this unpleasant oil had coated the defenders making it almost impossible to hold their weapons and giving rise to a temporary gas alarm, so pungent was the oil.’1

Surrounded by the enemy on four sides, the battalion had resigned itself to fighting its last battle when Lance Corporals Ernest Barnfield and Reginald Mayo – who had been detached with their platoon to brigade HQ – arrived at the Mairie with orders to withdraw to Bambecque. The two men had volunteered to get a message through to the battalion and had taken nearly five hours to cover the three miles from le Reit Veld, an exploit for which both men were subsequently awarded the MM. Mayo was soon afterwards shot in the hip and eventually captured.

But withdrawing was no easy matter. By 10.00pm the enemy were well established by the church in the western end of the village. Buxton, well aware of the need to keep the village clear in order for the battalion to escape, ordered a counter-attack which pushed the enemy back at the point of the bayonet. ‘The enemy,’ wrote Major Priestley, ‘had entered the churchyard and tried to get down the village street; this was stopped by heavy Bren gun fire, but he did establish himself in the end houses, they were evicted by a counter-attack with bayonets.’

Second Lieutenant Michael Shephard, who was later featured in the Gloucester Citizen, described how the Gloucesters charged past burning houses with the men shouting ‘Up the Gloucesters’. In the light of the burning buildings he saw several German soldiers being bayoneted and all around him there were explosions from German stick bombs accompanied by the whine of machine-gun fire. ‘Everywhere, our men were doing the same thing, bayoneting, shooting and bombing.’ Three such charges were made, led by Captain Charlie Norris, Lieutenant Tony Dewsnap the Intelligence Officer and Lieutenant Donald Norris – brother of Charlie – respectively, all of whom were wounded.

Sometime after the counter-attacks 32-year-old Major Anthony Waller, who was the most senior officer killed at Ledringhem, was engaged by an enemy patrol at the back of the Mairie when he was badly wounded in the head along with Guy Buxton who was wounded in the leg. Sergeant Ivor Organ remembered the moment Waller was hit:

‘We heard shouts and screams from behind a copse; two of our men were down. For one of them there was nothing we could do, but we took the other one to the cellar in the school, where the floor was already covered with wounded. Some were already dying in spite of being treated by the doctor who was working by candle light. The soldier we had brought in was none other than Major Waller [commanding HQ Company] who soon breathed his last, his head one bloody mass. Returning to the trench I saw that during my absence a grenade had wounded all the men there.’2

The battalion was now closely surrounded by a large force of enemy; Buxton’s problem was to disengage the battalion from the fighting long enough to assemble his men and issue orders for the withdrawal. Fortunately, during a lull in the fighting, a brief window of opportunity allowed him to do just that. Major Priestley described the moments after the battalion moved off:

‘Two medical orderlies were left behind with the three wounded officers and the men in the school who were too severely injured to move. The remainder of the battalion moved off. Smoke from the burning buildings in the village helped cover movements. Complete silence was enjoyed and the battalion left the orchard at 1.15am. The battalion column was single file and fairly lengthy. Captain [Leslie] Hauting (Adjutant) kept the column on the right route.’3

The odds against the chances of this column of men reaching British lines were high. Bambecque lay nearly 6 miles to the north-east, many of the 13 officers and 130 men were wounded, all were exhausted and it was dark. But five hours later, having found a gap in the German encirclement, they reached Bambecque via Herzeele at 6.30am on 29 May, complete with prisoners whom they had taken en-route. It was a feat of arms that must rank alongside that of the 2/Dorsets. Their arrival was recorded by a delighted Captain Bill Haywood who had just been appointed adjutant of the 8/Worcesters and was convinced Buxton’s battalion had been ‘utterly annihilated’:

‘They were dirty and weary and haggard, but unbeaten. Their eyes were sunken and red from lack of sleep, and their feet as they marched seemed to me no more than an inch from the ground. At their head limped a few prisoners with Hauting the Adjutant, in close attendance ... The column halted and two of the Germans flopped down exhausted, though a captured officer remained standing and tried to look defiant. I ran towards Colonel Buxton, who was staggering along, obviously wounded. He croaked a greeting, and I saw the lumps of sleep in his bloodshot eyes.’4

There was one more journey for the battalion and that was to Dunkirk where they were evacuated. Altogether around forty men of the Gloucesters are identified on the CWGC database as having been killed between 26–29 May 1940. Twenty-four – including Major Anthony Waller – are buried at Ledringhem Churchyard Cemetery.

The 2/Royal Warwicks arrived at Wormhout just before dawn on Sunday 26 May. At command level there had been a change of leadership and Major Phillip Hicks now commanded the battalion in place of Lieutenant Colonel Dunn who had been evacuated at Hollain with a burst gastric ulcer. It was raining when Captain Dick Tomes and the battalion’s officers met Major Hicks in the town square to hear his orders, Tomes recalling that ‘most of us fell asleep on the pavement where we halted.’ The companies were allocated defensive positions on the western side of town while 8/Worcesters under Lieutenant Colonel James Johnstone were deployed on the eastern approaches. Even though the infantry were supported by Captain Sir John Nicholson and his two platoons of machine gunners from 4/Cheshires and a few guns from 53/Anti-Tank Regiment (Worcestershire Yeomanry), the two battalions still had a large perimeter to defend and life was not made any easier when C Company of the Warwicks under Captain Charles Nicholson, was ordered to move to Esquelbecq, a small hamlet about a mile and a half to the west.

Nicholson’s move required some shuffling around on the Wormhout perimeter but even when this had been accomplished there were still holes in the defences. Haywood wrote afterwards that Colonel Johnstone thought ‘it likely that the battalion was about to do its final job’ and wished all his officers good luck in the coming battle. ‘There was no hand-shaking, no solemnity, no fuss of any kind.’

As far as battalion headquarters were concerned there were plenty of locations to choose from the Warwicks took over a large house on the Esquelbecq road while the Worcesters’ HQ based itself at a gardener’s cottage in the grounds of a château on the D55 where Brigadier Hamilton had established his HQ. Just after midday on 27 May Wormhout was attacked by a wave of German aircraft that bombed the centre of the town and almost completely destroyed it. Fortunately this had little effect on the troops in terms of casualties but on surveying the wreckage Dick Tomes thought the place to be a shambles:

‘Every house was either wrecked completely or partially and the square was a mass of debris, fallen trees, telegraph wires and smashed civilian vans. A few civilians were lying in the road either dead or badly wounded, and there must have been a lot killed in the houses. Most civilians were attended to by a French First Aid Post but our own RAP took in a few. We moved our HQ out of the house and to the far end of the park.’5

That evening C Company reappeared from Esquelbecq having been ordered to move north to Bergues to guard divisional headquarters. Nicholson reported the presence of enemy reconnaissance parties west of the railway station, confirming a captured operational order already in Hamilton’s possession indicating that Wormhout was the next target.

Soon after dawn on 28 May the inevitable shelling preceded the infantry attack which came in from the Esquelbecq direction forcing Captain Edward Jerram’s B Company into contact with the enemy. The road block on the Esquelbecq road came under fire from German AFVs which appeared to be using a stream of refugees as cover. They were shot up by a 2-pounder anti-tank gun and machine-gun fire from Lieutenant Charles Dunwell’s platoon but in the confusion a handful of German infantry managed to get away and establish themselves in a nearby house. There is no doubt that the initial German infantry attack was held up by the Warwicks and the machine guns of the Cheshires, so much so that Obergruppenführer Josef ‘Sepp’ Dietrich, commanding the 1st SS Division Leibstandarte Adolf Hitler (SS-LAH), made the decision to see the situation for himself. As he approached the outskirts of Wormhout his vehicle was halted by the B Company roadblock giving Gunner Rawlinson plenty of time to aim and hit Dietrich’s vehicle, kill the driver and allow B Company to bring the remaining vehicles under a hail of rifle and machine-gun fire.

Dietrich and Max Wünsche, who was acting commander of 15 Kompanie, sought refuge in the nearby ditch which, fortunately for them, was deep enough to provide protection from the barrage of fire now being directed on them. All efforts to rescue the two officers ended in failure and at least three armoured vehicles from 6 Kompanie were knocked out by the Worcestershire gunners during the attempt.

The action now spread along the whole of the Warwicks’ front as the attack was pressed home by three battalions of the SS-LAH, from the 20th Motorised Division and the 2nd Panzer Division. Although by noon the Warwicks’ positions were still relatively intact it was not long before German armoured vehicles began pushing through the gaps in the line and in the process destroying the Worcestershire Yeomanry’s anti-tank guns. But it was on B Company that the enemy focused the bulk of its effort using the Esquelbecq road to gain access to the town centre and in the process rescuing the hard-pressed Dietrich and Wünsche from their roadside ditch. Corporal Bill Cordrey described the advance of German armoured units:

‘Everyone was firing now and I had my sights on the centre tank. I couldn’t miss. I was giving it the whole round, and although I knew it was a bull’s-eye the tank kept coming as if nothing had happened. Our ammunition, in spite of what the top brass had told us in England, was useless against armour. The situation was becoming critical and we were pinned to the spot by enemy fire. What should we do? Go while there was still time or wait to be massacred?’6

Cordrey and his section took the only course of action open to them and got out, but not before they watched the tanks drive straight over a neighbouring position killing and wounding the men, some of whom were crushed beneath the tanks. At battalion headquarters Dick Tomes was philosophical about the outcome of the battle:

‘The shelling increased. A smoke screen was laid and all the companies reported tanks, either attacking or preparing to do so, with infantry behind them. We had no tank obstacles and most of the 25mm and 2-pounder Anti-Tank guns had been destroyed and their crews killed after their fire had been cleverly drawn. It became obvious that we could not stop a tank attack and would be merely overrun. After all we were but a few scattered infantry posts, without our mortars, no carriers, very inadequate artillery support and no air or armoured support whatsoever. But the battalion had at any rate delayed the advance.’7

Many were killed in the last desperate struggle; 47-year-old Major Cyril Chichester-Constable commanding A Company was last seen firing his revolver at the advancing enemy; Captain David Padfield lost his life while making his way back to A Company lines from battalion HQ and Charles Dunwell was killed with his platoon on the Esquelbecq road. At 4.00pm Major Hicks sent a last message to brigade headquarters and with no word from any of his three companies, prepared for the last stand. Dick Tomes was with him:

‘Then two armoured cars appeared on the left and a real hurricane of fire descended upon us as they located our position. Luckily most of this seemed to go over our heads. Most appeared to be tracer ...I saw a man with an anti-tank rifle – I didn’t know where he had come from – I told him to follow me and started off up the road towards the armoured cars which were firing from behind a hedge some 200 yards away. He couldn’t see where they were so I lay down in the middle of the road covered by a derelict truck. I fired two of the remaining three rounds ... I was feeling curiously exhilarated now and still had a rifle and 50 rounds of [ammunition] which I had taken off a carrier. After placing the man [Private Fahey] with the anti-tank rifle in position I got behind a hedge and fired off practically the whole bandolier at the crews in the turrets of the armoured cars – one became ditched – and at various vehicles and motor cycles coming up the road.’8

It is quite possible that this last act by Tomes may have wounded the commanding officer of the 2nd Battalion, SS-LAH, Sturmbannführer Schützek, whose head wound sustained near the square at Wormhout left the battalion leaderless and in some confusion. Looking to his left Tomes saw two tanks heading towards him across the field and having directed his fire onto them ran towards Hicks who was shouting for him to come back. With German armoured vehicles all around them Hicks gave the order to those who were able, to make a dash for it. Joining them, Tomes was climbing a fence when a blow on the head knocked him unconscious.

The Worcesters were more fortunate. Seeing little point in sacrificing another battalion in what Haywood described as ‘futile attempts’ to rescue the Warwicks, they were withdrawn to Bambecque but not before they were able to leave a memento in the form of two of Captain Ted Berry’s carriers:

‘Our lugubrious Ted accepted this dangerous task with his characteristic lack of eagerness, and his equally characteristic lack of hesitation. Off went the carriers in the pouring rain and in a moment or two we heard their Bren guns firing. Ted found the Bosche in Wormhout still unorganized, and he drove round the square, gunning them as they ran into houses and shops. Not long afterwards Ted was back, cadging a cigarette from me.’9

Tombes was captured along with Captain Tony Crook, the battalion medical officer, after he had been taken to the RAP in the park. Others, such as Hicks and Jerram, managed to evade capture but of the three companies that had fought at Wormhout only 7 officers and 130 men were finally evacuated from Dunkirk.10

Halfway along the D17 between Esquelbecq and Wormhout is a memorial that stands as a permanent reminder of the appalling conclusion to the battle at Wormhout. Many historians feel that the nature of the battle changed after Deitrich was forced to take cover on the Esquelbecq road and heavy German armour was required to subdue the Warwicks’ defence. That may well be the case, but whether the subsequent massacres were a direct result of the indignity suffered by Deitrich and the wounding of Schützek is a matter of conjecture. However, there is little doubt that the SS troops who took Wormhout were in a murderous and vengeful frame of mind which manifested itself in the form of the brutal behaviour which came to be associated with the Waffen-SS.

Several contemporary accounts highlight the incidents which were witnessed by Private Arthur Baxter of the Worcestershire Yeomanry when an officer and the driver of a British 15cwt truck were murdered after they had surrendered and another soldier was shot after refusing to hand over his watch. In another incident Lance Corporal Thomas Oxley of 4/Cheshires was amongst a group being driven into the main square from the Wormhout-Cassel road when they were fired upon by a group of German soldiers at 1.50pm. Most of the men on the trucks were killed or wounded but Oxley and three others were thrown off as his vehicle lurched round a corner in its attempt to get clear. Finding themselves surrounded, they raised their hands in surrender:

‘After a matter of minutes, they fired upon us. Whether they all fired, I cannot say, but definitely one of them, who I had been watching, let go a burst on his Tommy-gun at the four of us. I was hit twice on the arm and leg, and was knocked out immediately ... After coming to, I saw some Germans sitting around the shop fronts ... Three Germans brought an English sergeant who was not known to me, out of a house. He appeared to be badly wounded, and a German officer immediately shot him down with a revolver. He emptied the revolver into the sergeant while he lay on the ground.’11

If his account is correct and this did take place at 1.50pm, then the German attack must have already broken through and entered from the south, however it appears they left the square at about 4.50pm after gunfire was heard nearby, giving Oxley and another man the opportunity to escape.

Hugh Sebag-Montefiore points out that if these incidents had been the only acts of violence perpetrated that afternoon then they could have been viewed to some extent as the result of soldiers reacting with brutality in the immediate aftermath of a fierce battle. After all, it is those few moments following the act of surrender which are the most dangerous for the defeated soldier. Tragically this was not to be the case with some fifty men from D Company whose surrender had already been accepted near the Wormhout-Cassel road. As this group were being marched into the town they witnessed fifteen to twenty men being lined up against a wall and shot, which not only left them numb with horror, but wondering if they too were to be dealt with in the same manner.

The D Company men were soon joined by Gunner Richard Parry from D Troop, 69/Medium Regiment (Caernarvonshire and Denbighshire Yeomanry) which had been ambushed at Wormhout on the way to Dunkirk. Under the command of 31-year-old Captain Heneage Finch, the 9th Earl of Aylesford, who was killed in the lead vehicle, the surviving gunners were ordered to scatter and make their escape. Parry headed towards the Penne Becque, swimming downstream in an attempt to get away but in vain; wet and exhausted he was taken prisoner. Private Edward Daly, who surrendered with A Company after their ammunition had given out, remembered being shot in the shoulder by a German soldier armed with a revolver and then marched to where the remnants of D Company were being held:

‘From this point, with some other ranks of the Cheshire Regiment and the Royal Artillery, we were marched to a barn some distance away, rather more than a mile I judged. According to my estimate there were about ninety altogether who were herded into the barn, more or less filling it ... Captain Lynn-Allen who was commanding D Company [Warwicks] and who was the only officer amongst the prisoners, protested against what appeared to be the intention, namely to massacre the prisoners.’12

Private Albert Evans recalled the forced march to the barn on la Plaine au Bois during which several men – despite the fact that many were badly injured – were bayoneted or clubbed with rifle butts by the accompanying soldiers from 8 Kompanie, 2nd Battalion SS-LAH.

The exact chronology of the cold-blooded slaughter of British soldiers which took place in and outside the barn on the afternoon of 28 May 1940 is difficult to piece together accurately, but the testimony of survivors paints a grim picture of the horrific circumstances that unfolded in the barn. It began with the surrounding SS infantrymen throwing grenades into the tightly-packed structure which, apart from killing and maiming those who were closest to the explosions, shattered the arm of Albert Evans. These first grenade explosions killed 36-year-old Rugby born CSM Augustus Jennings and Sergeant Stanley Moore who courageously shielded their comrades with their own bodies; their sacrifice undoubtedly saving a number of men from being killed. Gunner Parry counted five explosions, one of which blew him through a gap in the side of the barn where he witnessed a group of five men being herded out of the barn and shot. ‘I could see them round the back of the barn, and their last act, was to turn round of their own accord, and face the firing squad.’

Albert Evans was standing next to 28-year-old Captain James Lynn-Allen when the officer grabbed him by the arm and dragged him out through the corner of the barn:

‘Captain Lynn-Allen practically dragged or supported me the whole way to a clump of trees, which was about 200 yards away. When we got inside the trees, we found there was a small stagnant and deep pond in the centre. We got down into the pond with the water up to our chests ... Suddenly without warning a German appeared on the bank of the pond just above us showing we must have been spotted before we gained the cover of the trees. The German who was armed with a revolver, immediately shot Captain Lynn-Allen twice ... I was hit twice in the neck, and already bleeding profusely from my arm, I slumped in the water.’13

Lynn-Allen was dead but Evans survived by initially feigning death and later crawling to a nearby farm where he received medical attention from a German ambulance unit.

It is still unknown how many men were killed in the barn but the figure is thought to be between eighty and ninety. Altogether there were some fifteen survivors, some of whom came forward to give their testimony, and others who perhaps preferred to forget behind the wall of anonymity. The dead were buried in a mass grave on the Plaine au Bois but as their identity tags had been removed many remained unidentified when the grave was exhumed in 1941 and the bodies reburied locally. Realising a crime had been committed it is thought the Germans dispersed the bodies resulting in the exact location of all the dead being lost. It is possible that many may be amongst the forty unknown burials at Wormhout Communal and Esquelbecq Military Cemeteries and it is not beyond the realms of credibility to assume that some are still buried somewhere on the Plaine au Bois.14

The War Crimes Interrogation Unit began reconstructing the events at Wormhout in 1943 but regrettably failed to bring any of the 2nd Battalion SS-LAH to justice. Several had been killed on the Eastern Front by the end of the war and others, such as Josef Deitrich, managed to escape the noose protected by an oath of silence and the failure of the survivors to positively identify any of those who had actually committed the crime. Hauptsturmführer Wilhelm Mohnke who was in command of the 2nd Battalion SS-LAH at the time of the atrocity led a full and active life after his release from Soviet captivity and died, aged 90, in 2001 in a Hamburg retirement home.

On the same day as the Wormhout massacres were being perpetrated Brigadier Norman and the 1/Fife and Forfar Yeomanry under Lieutenant Colonel Ronald Sharp, were ordered by Major General ‘Bulgy’ Thorne to travel north from Cassel to Socx where enemy tanks were reported to be menacing the flank of the Dunkirk Corridor:

‘At about the same time the Welsh Guards received orders from III Corps to go to the same area to “clear up the situation”. I contacted Colonel Copland-Griffiths who agreed to move under my command. As 5/RHA in the area could no longer be protected by the reduced Cassel garrison their CO also agreed to move under me. I agreed to leave the East Riding Yeomanry at Cassel because 145 Brigade could no longer hold their perimeter without their help.’15

The move of Norman’s composite brigade was fraught with difficulties particularly as the enemy were by now across the main Cassel-Bergues road forcing the convoy to move along minor roads to the east which were jammed with refugee traffic and horsed French artillery units. Norman was well aware that if the ‘Germans had attacked us on the move there would have been a complete disaster’. As it was, a journey of 15 miles took five hours to complete.

It was dark by the time Norman met his commanding officers at Vyfweg (les Cinq Chemins) where he explained the brigade was to defend a 5-mile sector between Bergues and West Cappel. Regardless of the addition of 6/Green Howards – who had arrived before Norman – it must have been apparent to the brigadier that he did not have enough men to hold the sector for more than a few hours. The 5/RHA guns he placed behind the Canal de Basse Colme, leaving two sections in forward positions ready to engage German AFVs.

Norman’s initial meeting with Lieutenant Colonel Mathew Steel, commanding the Green Howards, was not one which filled him with confidence, especially after Steel explained his battalion had little combat experience and had been brought back to Vyfweg from the beaches where they had been told they were going home. ‘They will stay just as long as they do not see a German,’ said Steel. ‘At the first sight of the enemy they will bolt to a man. I thought it only fair to let you know.’16 Serving with the Green Howards at the time was Lance Corporal Stanley Hollis who was Steel’s despatch rider. Promoted to sergeant when they got home, Hollis would go on to be awarded the VC with the same battalion during the Normandy landings in June 1944.

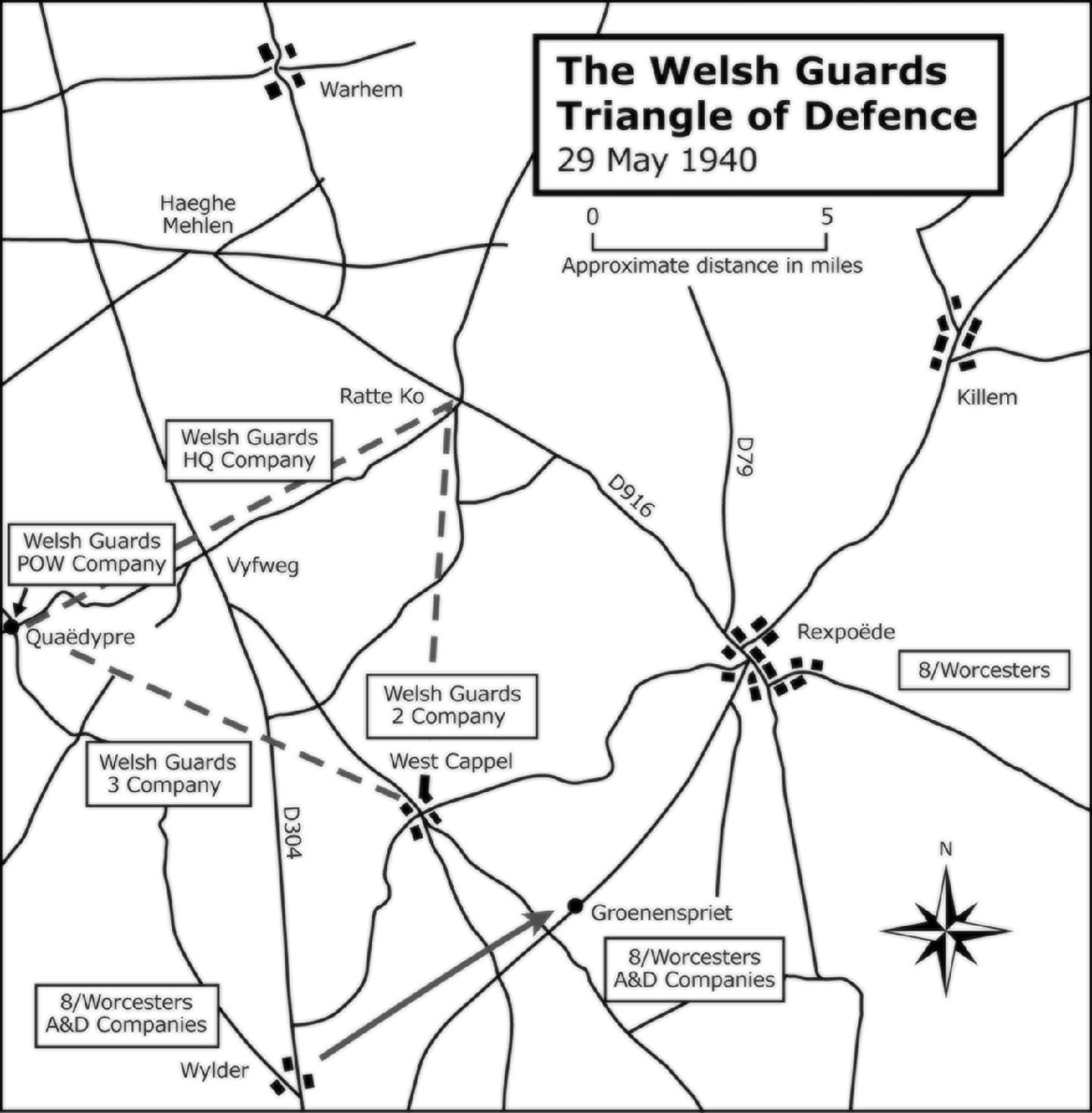

Giving Copland-Griffiths the freedom to deploy his battalion as he saw fit, Brigadier Norman established his headquarters at the Vyfweg crossroads, a hamlet that was contained within the wide triangle of ground around which Copland-Griffiths had deployed his Welsh Guards. With strong-points at Vyfweg, West Cappel and Ratte Ko (la Forge du Rattekoot) and using the Fife and Forfars’ tanks and 3 Company to fill the gaps, a triangle of defence was created. It was, however, very fragile: many of the 3 Company platoon posts found themselves in isolated farms with orders to hold on as long as possible before retiring. Even with the main body of 8/Worcesters south of Rexpoëde there was still a one and a half mile gap between them and West Cappel which made the whole defence a rather tenuous arrangement, an opinion Lieutenant John Miller may well have agreed with at his isolated platoon post at the Hoymille crossroads south east of Bergues!

However, Copland-Griffiths’ battlefield instinct proved to be correct in that West Cappel appeared to be the focal point of the main German attack, although, there had been earlier indications of this from the skirmish at Wylder, when the Worcesters’ A Company – with three anti-tank guns from 211/Battery – was involved in a three-hour battle before they were withdrawn towards Groenenspriet by Captain John Farrar.

Sent to the small village of West Cappel Welsh Guards Captain Jocelyn Gurney and 2 Company, arrived in a small convoy of trucks early in the morning of 29 May. Keeping HQ Company and the RASC drivers with their vehicles in the grounds behind the seventeenth century château, he positioned PSM Hubert ‘Bert’ Maisey with 6 Platoon to cover the northern approaches and 19-year-old Second Lieutenant Rhidian Llewellyn with 5 Platoon to cover the south and south-eastern roads towards Wylder and Bambecque. This left Second Lieutenant Nick Daniel and 4 Platoon to dig in around the area of the church. The first sign of enemy activity came at 12.30pm when 5 Platoon reported a German patrol on their front but it was not until 3.00pm that Llewellyn reported that a strong force of enemy tanks and infantry were advancing from the direction of Wylder. Concerned that they would be overrun, Gurney sent a runner and ordered 5 Platoon to withdraw to the château.

From Llewellyn’s account it appears that the withdrawal was going relatively smoothly until his last section was about to leave:

‘The section was shot up as they went down the road ... I raced back to the last Bren gunner, Guardsman Warwick, who was firing in bursts to his front. Our time to leave had come but which way to go? I knew our retreat had now been cut off and as Warwick had been firing for some time I found it difficult to get him out of his slit trench, he was very stiff. I picked up his Bren for him ... I put the gun into the hip firing position and Warwick was close at hand with loaded magazines. We worked our way down the hedge towards the church and the 4 Platoon position. When Warwick and I came out of the [church] gateway, the lane was full of Germans. I fired several bursts at them and sent them scampering down the lane. I fired after them and used up a full magazine. We ran into more Germans at the rear of the houses, some were firing at us and one or two with their hands up. We ran through them and I kept firing all the time.’17

Llewellyn and Warwick made it back to the 4 Platoon position where there was a short conversation with Nick Daniel who by this time was coming under considerable pressure himself – presumably from the same body of German troops that Llewellyn had just dispersed with his Bren gun.

Llewellyn then made his way back to the rear of the château to report to Captain Gurney at HQ Company; telling him to wait for his return, Gurney left to assess the situation facing Nick Daniels and 4 Platoon for himself:

‘I crawled away towards the moat and as I was in the ditch two tanks came into the garden and shot at me. I dived under the moat bridge and there I was, with a tank pounding at the bridge above me; luckily he didn’t see the moat, went into it and stuck; but his gun was trained on the château door. Eventually my servant crawled to me and I decided that we must make for the château. As we got out of the moat Daniel and some of 4 Platoon came in. They had a man on a stretcher and I said we must make a dash for it and picked up the front end of the stretcher. Guardsman [Ivor] Llewellyn had the other end. As we made for the door of the château the tank in the moat fired and caught Llewellyn and killed him.’18

Daniels had been lucky to get away with a few survivors from his platoon and had no idea that PSM Maisey and 6 Platoon had already been overrun in the north of the village. But there was little time available for empathy as tanks now crashed through the château grounds scattering all before them. At the same time as Gurney and his party were making a break for the château door another tank moved in on HQ Company and ‘shot them up’ as they ran for cover. Llewellyn again:

‘Guardsman Andrews and I were the last to leave Company HQ and we worked our way back to the château but reached the bridge over the moat at the same time as the tank, fire from which wounded me in the right hand. Andrews and I dived under the bridge from where Captain Gurney and party had just made it to the château door some minutes before.’19

And there they remained for the next two hours while the battle raged on above them, Llewellyn admitting they were most concerned their presence would be discovered at any time by the tank crew.

Meanwhile at Groenenspriet, less than a mile to the south west, 30-year-old Captain John Farrar and two companies of Worcesters were putting up a spirited defence against tanks and infantry which had encircled them. Fighting back with Boys rifles, at least one tank was put out of action and its crew shot up by Private Turton before fresh enemy infantry was seen to arrive in lorries:

‘At 5.15pm Captain Farrar wrote a message saying that three large and five small tanks had passed his HQ and were heading due east. A few minutes later other tanks closed in on D Company HQ and set it on fire. All platoons of that company were overwhelmed, but men in twos and threes continued to resist. Captain Farrar, we gather, refused to leave and was last seen firing an anti-tank rifle at enemy tanks. At 5.30pm enemy infantry made a strong attack on Groenenspriet. Many of these, wearing British uniform, were shouting ‘British’ and pretending to surrender. They were allowed to approach more closely, but their colleagues in the rear spoilt the ruse by opening fire. [The] A Company Platoons returned the fire and a heavy engagement ensued until about 6.00pm. By this time both A and D Companies were so badly cut up that further organized resistance was impossible, and the survivors from the scattered platoons of both companies – 3 Officers and about 60 men – arrived by fours and fives at battalion HQ to re-organize.’20

At West Cappel a lull in the fighting at 7.30pm enabled Llewellyn and Andrews to creep out of the moat undetected and enter the château by a side entrance:

‘Inside the chateau we now had about 35 of our people, these included Captain Gurney, Nick Daniels and a few of 4 Platoon, Guardsman Savage, a stretcher bearer who did magnificent work throughout the battle, PSM Christian and most of my platoon ... The company had already lost about 100 men ... By 9.00pm Captain Gurney thought the Germans were about to renew the attack on the château, so while he and PSM Christian covered our withdrawal we crawled down the steps ... Private [Austin] Snead reported the Germans were creeping closer and they opened fire. We fled crossing the road under fire and met up near the 6 Platoon position from where German voices were heard.’21

It would appear that the first contact with the enemy at the Vyfweg crossroads came much earlier than at West Cappel. Brigadier Norman noted that the first indication of an enemy attack came at about 7.00am when a crowd of Green Howards came running past his position:

‘One of their CSMs and I did our best to rally them and get them into neighbouring ditches – then came the German tanks that had driven them in. I and Major Murray Prain, 1st F & F Yeomanry, who was with me, got into a friendly deep ditch which had water in the bottom. As the tanks approached firing their machine guns we watched them under our tin hats over the edge of our ditch firing at them with a Boys rifle. The bullets bounced off their front plates like peas. When they got to within thirty or forty yards they could not depress their guns enough to hit us. We went to the bottom of it and lay flat on our fronts in the water, I wondering what it would feel like to have bullets going into my behind and coming out of my mouth.’22

Fortunately for Norman it was a feeling he never had to experience as at that moment the forward guns of 5/RHA opened up on the tanks forcing them to withdraw and both men – very wet by this time – emerged intact.

According to the 1/Armoured Reconnaissance Brigade war diary, later that morning Norman moved his HQ from Vyfweg ‘towards Ratte Ko’ which the diary says was forward of the Welsh Guards and the Fife and Forfar headquarters. There is also a suggestion in Ellis’s account that the Welsh Guards Prince of Wales Company was withdrawn from Quaëdypre and moved further east, although this is not made clear in the war diary.23 At 6.00pm Major General Thorne arrived for a roadside conference with Norman at which time it is likely that plans for the withdrawal of the brigade were discussed. Sometime later Captain Jimmy Haggas – whom we last met at Hondeghem – was asked by Copland-Griffiths to take his adjutant, Captain Archie Noel, to brigade HQ for further orders:

‘On our way we were fired upon by machine guns and I think some heavier stuff. I found Brigadier Norman with Lieutenant Colonel Sharp under heavy machine-gun fire. They were standing in a shallow pit. The brigadier gave us orders to take back to Copland-Griffiths instructing him to withdraw the Welsh Guards.’24

Minutes after Haggas left the crossroads Lieutenant Colonel Sharp and Captain Foster Jennings, the Fife and Forfar medical officer, were killed by a shell which obliterated regimental headquarters and wounded several others in the vicinity.25

Captain Otho Bullivant, the Fife and Forfar adjutant, thinks that the orders for a withdrawal were passed on to Norman’s units at around 7.00pm that evening when they moved north towards Bergues. Most managed to get away but German infantry rushed the Guards HQ Company building before the last group were able to leave, taking – amongst others – Archie Noel and RSM Richards prisoner.

But for the Welsh Guards at West Cappel it was a little more complex as they were by now surrounded and cut off from their escape route. Rhidian Llewellyn writes that they began their night march across country at 10.00pm, and during the journey they were forced to fight on at least two occasions as they passed through German lines. Inevitably the little party became fragmented in the darkness and, reduced to twenty-three officers and men, they arrived at the Canal de Basse Colme at 3.00am on 30 May. Llewellyn’s last words on the West Cappel episode simply stated that they reported to Copland-Griffiths on the beach at La Panne and the battalion sailed for England at 10.00pm that night. His award of the MC was announced with that of Jocelyn Gurney in October 1940.26

Near Rexpoëde, Captain Arthur Steele, a Liaison Officer with 144 Brigade, arrived outside the Worcesters’ HQ as it was getting dark. Haywood watched his arrival:

‘He pulled up quietly in the road outside, stepped out, ignored the enemy’s fire, calmly shut the door of the car and ordered it to be pulled off the road, then walked slowly into battalion HQ. He brought a message informing us that we were to withdraw at 8.00pm and gave us our route to Bray-Dunes on the coast ... From B and C Companies few escaped. B Company, which was widely deployed, fought on until its ammunition was exhausted, and then had no alternative but surrender, since the net was closed so tightly around it.’27

Private Bailey serving in the Signals Platoon was one of the lucky ones who got home to England and recalled the battalion’s last march to Bray-Dunes:

‘On May 30th the beach at Bray-Dunes was reached after a march of seven hours. There were about 100 men out of a battalion of 750 but eventually the number reached 150. There was no-one from B Coy but later seven men from C Coy arrived, some having had to stand up to their necks in water under a river bank to avoid being taken prisoner.’28