Chapter Thirteen

The Ypres – Comines Canal

25–28 May 1940

‘During the course of the afternoon we were subjected to an intense artillery bombardment. Although the holes we had dug were often blocked with earth from the explosions we only mourned the loss of one soldier. But a hundred paces to our right, seven men from the first platoon of 13 Kompanie were hit on a terrace where five were wounded and one killed.’

Feldwebel Muller-Nedebock IR 162 on being shelled

by British artillery on 27 May

In Chapter 6 the situation on the Lys and the breaching of the Belgian line at Courtrai – which left a dangerous gap of some eight miles on the BEF’s right flank allowing German units to cross the Lys east of the town – was touched upon briefly. Gort’s historic decision to send the four brigades of the 5th and 50th Divisions to the line of the Ypres-Comines Canal was almost certainly precipitated by the intelligence he was receiving regarding the Belgian collapse (the capture of documents by 1/7 Middlesex serving only to substantiate what was already suspected). Confirmation of the Belgian lack of resolve – if indeed it was needed at this stage – was also being fed back from the 12/Lancers, their two messages of 25 May making plain that von Bock’s Sixth Army units were exploiting the gap. The first message timed at 5.00pm stated that the Germans were pushing into the outskirts of Menin and advancing north through Moorslede with little or no resistance from the Belgians. If that were not bad enough, the second message received at 5.25pm advised that the Lancers were now becoming involved in an infantry battle between Menin and Roulers (Roeselare) ‘in which the Belgians are taking no part’.1

It was now clear that the Belgians were retreating north-east, away from the BEF and if Gort did not defend the line of the canal running north from Comines to Ypres then the BEF would be denied access to Dunkirk by von Bock and a military disaster of gargantuan proportions would ensue. The decision by Gort to send the 5th Division to the Ypres-Comines Canal was as significant to the outcome of the Dunkirk evacuation as Hitler’s Halt Order of 24 May would prove to be.

The canal had never been used since its completion in 1913 and much to the surprise of both German and British units was largely dry with a railway line running south from Ypres on its raised eastern bank. Yet in spite of being described as ‘a poisonous position to hold’ by Lieutenant Colonel George ‘Pop’ Gilmore commanding the 2/Cameronians, the canal did form a barrier of sorts and, amid the surrounding flat landscape, was the only line of defence available.

Major General Howard Franklyn was summoned by Gort late on 24 May and informed that the 5th Division was to hold the line of the canal and 143 Brigade was to come under his command. ‘It was now a matter of time’, he wrote, ‘as to whether the 5th and 50th Divisions could be brought into position before the arrival of the Germans. A subsequent discussion with Alan Brooke took place at Ploegsteert Château ‘on the grass with a map between us’ during which the commander of II Corps explained that ‘there were three German divisions advancing through Belgium with nothing to stop them except one British brigade, the 143rd, strung-out along the Ypres-Comines Canal on a front of ten thousand yards’.2

Brigadier James Muirhead, commanding 143 Brigade, was already acutely aware that his three battalions were ‘strung-out’ while they awaited the remainder of the 5th Division to arrive and no doubt sharing Franklyn’s hope that the Germans would not arrive first. In the event the British were only just in time and Muirhead may well have breathed a sigh of relief as his frontage was reduced to 3 miles of canal bank from Comines to Houthem.

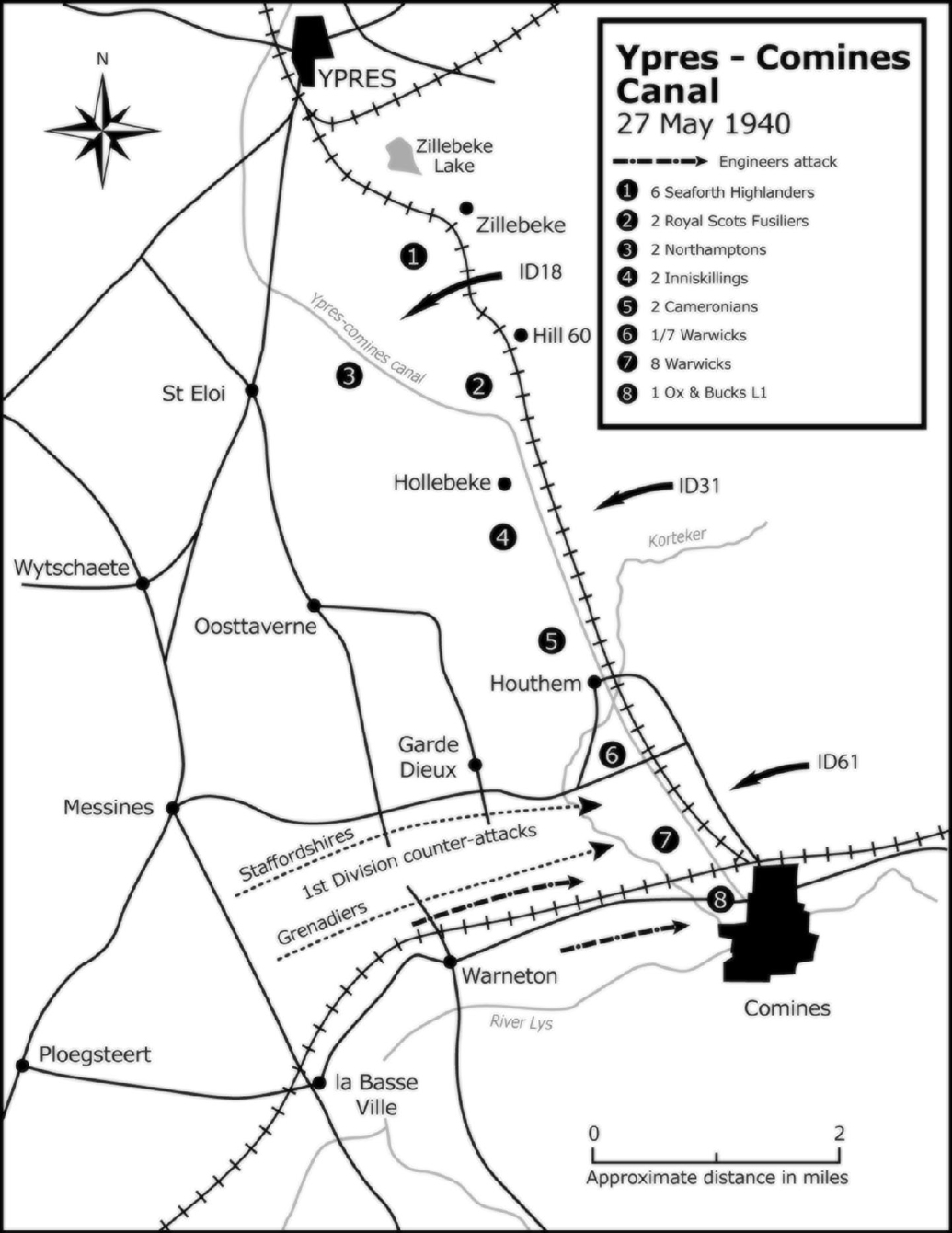

But even when reinforced by the 4/Gordons machine gunners, 97/(Kent Yeomanry) Field Regiment and 53/Anti-Tank Regiment, 143 Brigade historian Peter Caddick-Adams is of the opinion that its defences were ‘little more than a string of fortified farms’. Brigadier Miles Dempsey’s 13 Brigade covered the 2-mile stretch between Houthem to Hollebeke while Monty Stopford’s 17 Brigade dug in on their left and continued along the railway line to Zillebeke, 3 miles south-east of Ypres. The 50th Division did not begin arriving until 27 May when they took up their positions on the left of 13 Brigade in and around Ypres.

Against this thinly held line were the three divisions of Viktor von Schwedler’s IV Korps, the 61st Division – nicknamed the ‘Lion’ Division – and the 31st and 18th Divisions, all of which had fought in Poland. A fascinating account – referred to by Charles More in The Road to Dunkirk – relates to the initial direction of the attack by IV Korps on the canal. Apparently von Bock countermanded the orders which placed Ypres as the midpoint in the attack and ordered IV Korps to ‘continue straight ahead’ with the axis of the attack falling between Houthem and Hollebeke. It was fortunate for the British that he did as Ypres itself was largely undefended and the ground to the north practically unoccupied. More’s point that ‘Bock’s single-mindedness’ may have deprived the Germans of a significant prize serves to illustrate the ‘touch-and-go’ nature of a battle that could so easily have had a different outcome.

The attack on the 5th Division began early on 27 May and was marked by the absence of tanks. In the south, opposite 143 Brigade, the intensive fire from four battalions of IR 67 and IR 162 drove the forward defences back some 500 yards from the canal and overwhelmed the forward companies. Captain Purchas, commanding A Company of 1/7 Warwicks, was soon overrun defending the approaches to Houthem station as was B Company, positioned in Houthem itself. Captain Neil Holdich was commanding C Company on Purchas’s right flank around Soenen Farm:

‘The attack came in tremendous strength across the whole front. Heavy, almost continuous firing from rifles, automatic weapons and very quickly we were in serious trouble. 15 Platoon was badly hit ... 13 nearly as bad, but strongly supported by Sgt Flook, for whom I later got a ‘mention’. Suddenly two trucks came whizzing across from the right, into our area, containing a Lt Colvin and two heavy machine-gun sections from the 4th Gordon Highlanders. I thought they had arrived in answer to my earlier request for reinforcements from battalion HQ but no! He said none had given him orders for this but we seemed to be the only people in the area still fighting. Within minutes he had one gun up in the attic, and the other on the left of our building, slamming fire at anything that moved.’3

While the 1/7 Warwicks were battling to hold on to some sort of defensive line the 2/Cameronians on their left were having similar problems with their forward positions giving way. According to the Warwicks, the Cameronians had begun to withdraw in some disorder and Lieutenant Colonel Gerard Mole sent his intelligence officer, Lieutenant Blyth, who ‘intercepted the Colonel [George Gilmore] about 1 mile away and turned him round’. A damming indictment if taken on face value! In reality it is unlikely that Gilmore was retiring, indeed in his own account he writes that after his front-line posts were forced to withdraw the battalion was ordered by Brigadier Dempsy to form a new line on the Kaleute Ridge about 1 mile west of the canal which, in the heat of battle, was confused with the Warneton-Ypres road – where presumably Blythe found Gilmore preparing to counter-attack. Regaining the ridge was costly but together with the 2/Wiltshires and to some extent the Inniskillings, the 13 Brigade line was still intact at nightfall.

On the 8/Warwicks front it was a similar story: Major Kendall – who assumed command at Calonne from Lieutenant Colonel Baker – only remained in touch with his rifle companies for a short while before all communication ceased. Already seriously depleted before they arrived on the canal, the battalion could hardly muster 200 rifles. The last message from B Company at Woestyn was cut off mid-sentence as Captain Burge’s company fought hard to remain intact. For a time Corporal Bennett managed to keep the enemy infantry at bay with his Bren gun before capture became inevitable. Captain Cyril Lewthwaite’s C Company held out at company HQ most of the morning against units of IR 82 and IR 162 until they were overwhelmed at about 11.00am. Private William Watts was taken prisoner with Lewthwaite:

‘We were grouped together in the small kitchen looking to Captain Lewthwaite for guidance. He said, “I think we are now completely surrounded”. As he said this, the window was broken and a grenade or stick bomb was thrown in. There was a very loud explosion but as I was half lying against the staircase I felt no shrapnel. We were all very dazed and the front door was thrown open. There were lots of shouts of ‘Raus, Raus!’ We stumbled through the door, Capt Lewthwaite going first.’4

As far as Lieutenant Colonel Whitfeld’s 43rd Light Infantry were concerned the 27 May could not have had a worse start. Whilst visiting the forward companies Whitfeld was hit in the arm by one of the B Company sentries and had to be evacuated, command falling to 42-year-old Major David Colvill who perhaps had one of the most difficult sectors to defend. Much of Comines was on the eastern bank of the canal and German units were able to infiltrate through the town to its very edge. Feldwebel Muller-Nedebock’s account of his service with IR 162 indicates his Kompanie were on the lip of the eastern bank on the night of 26 May and next morning led the assault on ‘some farms beyond the canal which were not very closely defended’. He may well have been describing the attack on A and B Companies. But their advance was not without cost: he also writes of the large number of casualties his battalion sustained from the British artillery bombardment – which could have been the work of the guns of 97/Field Regiment or those positioned further west on the Messines Ridge.

Captain ‘Plum’ Warner, the adjutant of the 43rd was at battalion HQ at the farm owned by Jules Dugardin at Mai Cornet and writes that the situation was giving cause for anxiety as early as 5.30am:

‘Regimental headquarters was being sniped. Communications had broken down. No one knew where C Company [Major Richards] was. Regimental headquarters took up alarm posts at about 7.00am and soon afterwards the enemy was seen working up a stream in a north-westerly direction on the left flank. These were engaged with Brens and 3-inch mortars and must have suffered many casualties ... The posts held by regimental headquarters were shelled and there was a small amount of small arms fire. There were 12 casualties including Captain [Tony] Jephson, who was hit in the hand, and all were successfully evacuated ... information was very scarce. The situation was obscure and brigade sent no orders. At about 2.45pm the enemy were only fifty yards away [from the most forward post] ... Major Colvill decided, therefore, to withdraw to Warneton, where more effective resistance could be organised.’5

Colvill had little choice: both A and B Companies had been overrun and the company commanders killed and no word had been received from C Company, leaving him to assume the worst. In fact the worst had not happened and Richards – apparently surrounded and curiously unable to communicate with Colvill – broke out with the surviving men of his company and they fought their way back to Warneton. Lieutenant Giles Clutterbuck remained behind and was last seen firing his revolver at the enemy. Colvill, by now wounded and evacuated, left the battalion in the hands of Major Richards.

By the afternoon of 27 May the British line on the 143 Brigade sector had been pushed back almost a mile from the canal. Houthem itself was surrounded and IR 162 had occupied Bas-Warneton. At Ploegsteert Château Franklyn recalled coming to the conclusion that the situation on the right flank at Comines had become too precarious to leave to the defending troops on the ground and ordered the first of two counter-attacks. The first consisted of Royal Engineers from the 4th Division, the 13/18 Hussars with their light tanks and part of A Company from 6/Black Watch. Launched at about 7.00pm towards Bas-Warneton and Comines, Corporal Thomas Riordan from 7/Field Company (FC) remembered that ‘farms were burning and tracers were streaming in all directions’:

‘Our own and the enemy’s positions were intermingled so much that the Germans could not use their artillery to full effect and as dusk fell the enemy advantage of perfect observation was lost. 59 [FC] came up on the left of 7 [FC] and the Black Watch to take up their position walking through the smoke of the burning farm buildings with fixed bayonets. Major MacDonald 59 [FC] OC was mortally wounded. Major Gillespie [OC 7/FC] although wounded remained in action until 7/FC were relieved. 225 [FC] took up their position on the left of 59/FC but were not fired upon. It was now a matter of holding on and consolidating the position.’6

Franklyn’s rather sour comment that the first counter-attack ‘met with some success but was not strong enough to have any real effect’ is puzzling. Clearly he did not fully appreciate the strength and size of the attack although he grudgingly admits their attack ‘facilitated the much bigger counter-attack’ which he had planned for later that evening.

The second counter-attack involved the Grenadier Guards and the North Staffordshires from the 1st Division who had arrived at Le Touquet after a punishing march from Roubaix. Major Adair, commanding the 3/Grenadier Guards, received orders from Brigadier Beckwith-Smith to march immediately to Dunkirk and embark for England. It was while Adair was discussing the details with his adjutant that a second order arrived countermanding the first and placing his battalion under the orders of General Franklyn. Similar orders had been sent to Lieutenant Colonel Donald Butterworth, commanding the 2/North Staffordshires, both men and their battalions arriving at Ploegsteert by 7.30pm where they were briefed by Franklyn.

Forbes and Nicholson, in their history of the Grenadier Guards, underline the extent of the task now facing Adair and his battalion, circumstances that applied in equal measure to the Staffordshires:

‘Divorced from their own familiar division and brigade – whom they were not to see again until they reassembled in England – without even the time to snatch some food, the battalion now had a further 9 miles to march before they reached their start line, and from there it was a further 3 mile advance over unknown country to attack an enemy whose strength and exact positions were likewise unknown.’7

All that Adair and Butterworth knew was that the Germans had broken through and their battalions were to attack from La Basse Ville – Messines road with the Staffordshires on the left and re-take the ground up to the canal.

Advancing with 1 Company (Lieutenant Richard Crompton-Roberts) and 2 Company (Captain Roderick Brinkman) in the lead, the battalion crossed the start line at 8.30pm with Brinkman using the railway line on his right as guidance. The first 2 miles was only interrupted by the addition of some of the Warwicks and the odd badly-aimed shot but as they drew closer to the canal the Grenadiers’ casualties began to mount and Brinkman was hit by a mortar fragment in his right eye and soon afterwards by machine-gun fire. It was probably the same fire that hit and killed Crompton-Roberts and wounded Lieutenant Aubrey Fletcher. Roderick Brinkman found he had very few men left when he reached the canal:

‘There was a cottage on the canal which seemed to be the centre of activity of some Germans. I had five hand grenades in my haversack and four of these I threw into the windows of the cottage. Those Germans who were not killed or wounded fled back across a small bridge on to the other side of the canal ... I sent a guardsman back to Major Adair, Sgt Ryder and myself then proceeded to crawl back to where I had left my reserve platoon. On the way back I was hit again through the back of the right knee and became unable to crawl or walk.’8

Butterworth’s Staffordshires must have crossed the start line a little earlier, the darkness cloaking any contact they might have made with Grenadiers. The battalion ran into heavy German artillery and mortar fire in the vicinity of Garde-Dieux but pushed on across the Kortekeer stream at Pont Mallet having picked up a number of Warwicks on the way. According to Henri Bourgeois some of the Staffordshires reached the canal but heavy casualties appeared to have pushed them back to where Butterworth stabilised the line east of Garde-Dieux. Likewise the Grenadiers consolidated their line on the low ridge overlooking the canal after some desperate fighting to clear the west bank of enemy.

As courageous as the second counter-attack was, it is likely that its success was, in part, due to the first attack. The Grenadiers’ advance on the right appeared to be more successful than that of the Staffordshires and this is probably due to the actions of 7 and 59/Field Companies, which reached the Kortekeer stream and in a few cases advanced beyond it. The first attack was much stronger than Franklyn originally thought, but had the Grenadiers and Staffordshires not counter-attacked and knocked the German 61st Division off balance, the British would have been in a much weaker position the next morning.

Further north, along Monty Stopford’s 17 Brigade sector, the canal bent back to the north-west, widening the gap between it and the railway line along which the 6/Seaforth Highlanders and 2/Royal Scots Fusiliers (RSF) were deployed, Stopford realising early on that the brigade had far too few men to hold the sector between them and the 50th Division at Ypres for very long. Assaulted by the German 18th Division, an early casualty was the battalion of Seaforth Highlanders whose rearward drift may also have been influenced by the retirement of the 13 Brigade units on its right. Poor communication was certainly responsible for some battalions confusing the movement of others for unneccesary retirement and withdrawal, which may have ultimately contributed to Stopford’s orders to retire to the line of the canal where the 2/Northamptons were in position. This was easier said than done for the RSF whose left flank company was on the infamous Hill 60 – one of the iconic landmarks in the defence of Ypres during the previous war:

‘By this time the forward companies were heavily engaged ... and before the operation could be carried out it was necessary to mount and deliver a local a counter-attack in order to give breathing space for the withdrawal. The commanding officer considered it inadvisable to use the reserve company for this purpose ... Therefore he decided to use the fighting patrol to deliver the counter-attack. This attack, gallantly led by Lieutenants [Richard] Cholmondeley and [Hamilton] Maitland-Makgill-Crichton, both of whom were killed, achieved the purpose at considerable cost, and the forward companies disengaged.’9

In his history of the RSF Kemp tells us that Lieutenant Colonel Bill Tod established his new positions on the west bank of the canal in the early afternoon where IR 54 engaged his forward companies. ‘In spite of the inadequacy of our position he [the Germans] was again successfully held, but before darkness fell contact had been lost with the brigade on our right [13 Brigade]. Forward elements of the enemy had crossed the canal and were pressing round both our flanks.’10

On the morning of 28 May few, if any, of the British troops would have heard the news that King Leopold of the Belgians had capitulated and arranged a ceasefire from midnight on 27 May. Not that the information would have affected Lieutenant Colonel Tod and the RSF who were preparing to make their last stand in what the 17 Brigade war diary described as ‘a small isolated farmhouse’. It was not until 1945 after Tod was released from captivity that he was able to relate what actually took place that morning:

‘At first light I extended what was left of the battalion and advanced from the farmstead, sending Ian Thompson and his carriers to try and contact the unit on our left. No sooner had we taken up a position on the edge of a wood than the German attack began. Very soon they had broken through our thinly-held position and at the same time had come round both flanks and were behind us ... I then decided that our only hope was to fall back on the farmstead again. There at least we could put up some sort of all-round defence. This was done and on the way back I was hit and knocked into a stream ... The situation soon became quite hopeless. The Germans were still around, the barn was full of wounded and our ammunition was all but expended. Rightly or wrongly, I surrendered. The time was about 11.00am.’11

Lieutenant Colonel Tod and the forty-five officers and men of the RSF who surrendered that morning would surely have applauded the action at Houthem involving 35-year-old Private Anthony Wynne of the 1/7 Warwicks. Much like Private John Lungley of the 5/Buffs at l’Arbret, Wynne was holding the first building behind the bridge and resolutely prevented any German attempts to cross the canal with his accurate Bren gun fire. He held out until midday on 28 May when he was killed by a shell. His body was buried in the canal bed and later reinterred at Esquelmes War Cemetery.

The lack of an effective German attack on 28 May provided the British with the opportunity to withdraw, the rain which had extended across the whole sector by lunchtime perhaps masking the movement of British units and reducing German enthusiasm for offensive action. Caddick-Adams writes that the Germans were unaware of the British departure which was certainly the case with Major Neil Holdich and C Company of the 1/7 Warwicks who received their orders to withdraw under the cover of darkness:

‘Over the next two hours I gathered everybody together and at 9.00pm we moved out. We got to battalion HQ in good order and all that were left of us crossed the Messines Ridge, on foot, in total darkness, by 10.30pm. As we reached our transport at the crossroads, two artillery shells crumped down, causing more casualties, but fortunately they were the last of the battle.’12

Although the casualty figures are vaguely reminiscent of those of the First World War, it should be remembered that three German divisions were held along the canal between 26–28 May by three depleted British infantry brigades. German casualty figures are estimated at 600 killed with the greater proportion from ID 31 and 61, IR 151 for example reporting 127 killed and wounded for virtually no ground gained at all. The British appeared to have had a similar number killed but over 600 were taken prisoner. Interestingly the battalion returns for June 1940 show that the 5th Division battalions involved in the fighting on the canal each mustered some 400 officers and men on arrival in England but whether this applied to the Warwicks is not clear as Cuncliffe reports that the 1/7 had lost almost half its fighting men and only fifty-eight officers and men of the 8th returned home with Major Kendall.

Ypres has been omitted from the story so far as German intentions appeared to be concentrated on the canal line to the south. The town was in the German 18th Divisional sector and apart from occasional shelling – the Menin Gate was hit twice for example – it was never seriously attacked. But from the British point of view the discovery by the 12/Lancers that the town was undefended apart from a handful of Belgian sappers accounts for the hasty movement of the 1/6 South Staffordshires to defend the town. The South Staffordshires were a territorial battalion embodied at Wolverhampton in September 1939 as infantry pioneers and their presence at Ypres has been almost completely overshadowed by 150 Brigade and the 12/Lancers and it may well have been their status as a pioneer battalion that saw them discounted from Ellis’ Official History.

The South Staffs spent the night of 26 May erecting tank-blocks from the stones intended for the reconstruction of the famous Cloth Hall in the Grote Markt and digging trenches on the old ramparts. According to the 12/Lancers war diary for 26 May, ‘B Squadron remained to hold Ypres at all costs’. They make no mention of the South Staffords who, like the Lancers were placed under Brigadier Cecil Haydon’s command when 150 Brigade arrived the next morning. The South Staffs continued to hold the ramparts from the Menin Gate round to the Lille Gate on the southern edge of the city and, although Ypres was heavily shelled during the day, no enemy advance was seen until that evening when troops began probing the British defences. German sources indicate the cyclists of 18 Aufklärungs-Bataillon came under fire from the Menin Gate – presumably from 150/Brigade Anti-Tank Company and the South Staffords – whilst heading north over the crossroads on the Menin Road at approximately 2.30pm. Fire was returned by two German AFVs and supported by the guns of 54/Artillery Regiment, who were just north of Zillebeke lake.

It was undoubtedly this action that gave rise to Lieutenant Smith and his sappers from 101/Field Company blowing the bridge at the Menin Gate which takes the N8 over the old moat. Positioned on the ramparts, Second Lieutenant James and 13 Platoon of the South Staffords would have had a grandstand view:

‘By afternoon advance units of the enemy were definitely within striking distance of the canal and there seemed to be no reason for further delaying the orders to fire the charges. The anti-tank guns were brought up and put into position at the Gate and at 4.00pm orders were given that the bridge at the Menin Gate should be fired. This was done with complete success and without causing any structural damage to the Gate but causing irrepairable damage to the car of the Colonel [of the] East Yorks, the machine being completely werecked by falling masonry.’13

On 28 May the 1/6 were still at Ypres but enemy pressure was increasing along the canal. At around lunchtime the Green Howards, on the south-eastern sector of the town near Zillebeke Lake, were attacked by units of IR 54 – the same regiment that had overrun the RSF that morning – and before long the South Staffs at the Lille Gate also came under fire. Due largely to the courage of Corporal Rushdon, however, who continued to bring fire from his Bren gun down on the enemy despite his wounds, the attack fizzled out.

The 50th Division battalions withdrew from Ypres in the early hours of 29 May, the 1/6 marching to Poperinghe where it was reunited with the B Echelon transport and Captain Derek McCardie, who would later achieve fame at Arnhem in command of the 2/South Staffords. Later that morning IR 30 entered Ypres through the Lille Gate and raised the Swastika over the Cloth Hall at 11.25am, finally achieving in a matter of days the occupation of a town that had been denied them for four years a generation previously.