Chapter Fourteen

The Final Line

27 May–3 June 1940

‘One of my section commanders asked what he should do with all the unopened tins and I was engulfed with a wave of hatred for the Germans. Why should these bloody bastards invade other people’s countries, destroy their homes, villages and towns and machine gun and bomb them on the roads, and take what did not belong to them?’

Lieutenant Jimmy Langley, 2/Coldstream Guards,

on the Canal de Basse Colme.

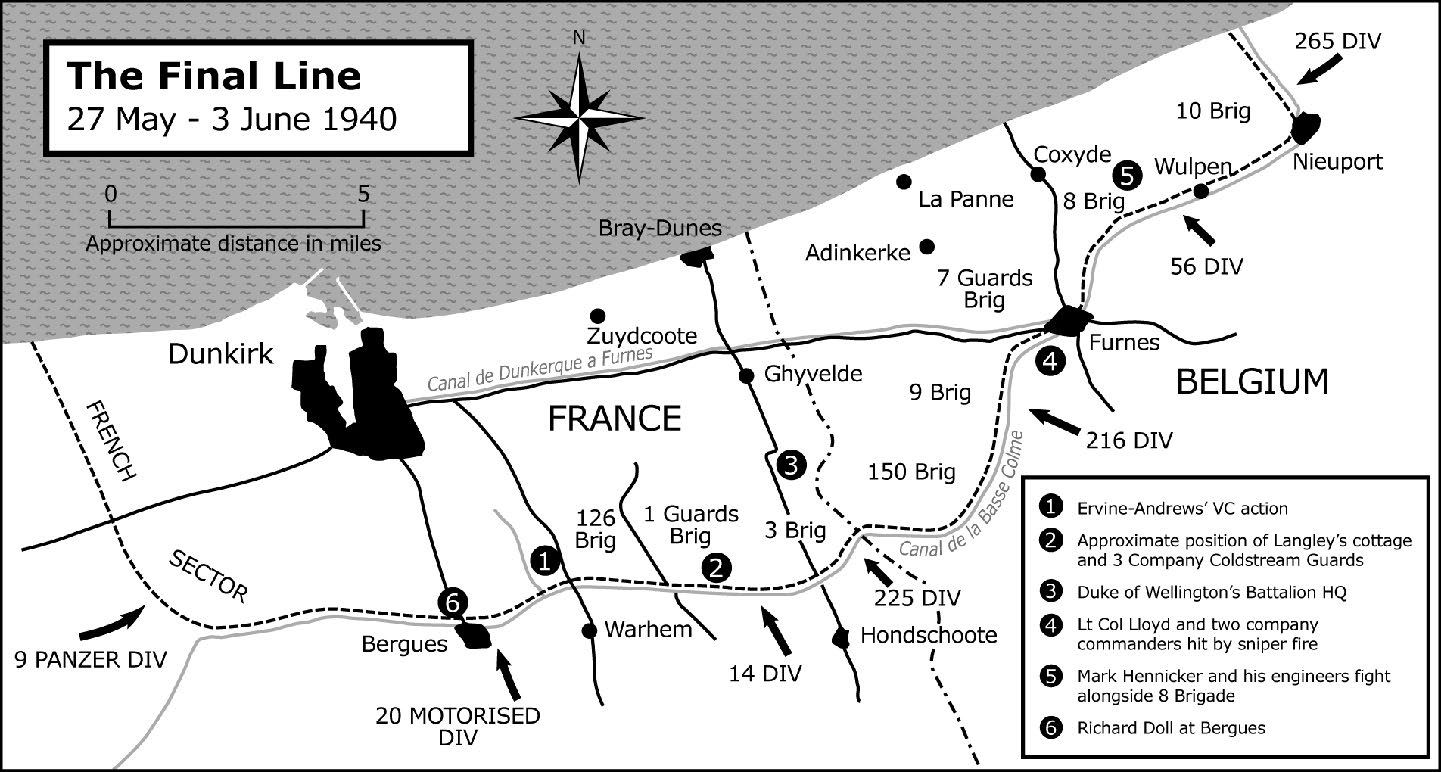

While Cassel was being prepared for battle by 145 Brigade on 27 May, the Hotel du Sauvage in the town square was the venue for a meeting between General Robert Fagalde and Lieutenant General Sir Ronald Adam where plans were agreed for the defence of Dunkirk. The perimeter line was to run between Nieuport Bains in the east and Gravelines on the western edge of the Dunkirk Corridor. Thirty miles wide and some 7 miles deep, the western sector between Gravelines and Bergues would be the preserve of the French while the British would defend the line from Bergues to Nieuport.

Lieutenant Colonel the Viscount Robert Bridgeman had already drawn up plans for Dunkirk’s defence which divided the bridgehead into three corps sectors. II Corps would defend the eastern sector and be evacuated from the La Panne beaches; I Corps in the centre would use Bray-Dunes as their evacuation point and II Corps, after holding the western end of the line, would evacuate from Malo-les-Baines. Adam established his HQ in the town hall at La Panne while Brigadier Frederick Lawson, who had been attached to Adam’s staff from the 48th Division, began the more difficult task of organising the defence line with those troops ‘filtering into the perimeter’.1

By 28 May Lawson had improvised a defence along the perimeter using gunners and infantry stragglers – dubbed ‘Adam Force’ – expecting that his scratch command would be reinforced with infantry units as they became available. His efforts were given an additional air of urgency by the Belgian capitulation which effectively opened the Nieuport flank to the German advance; fortunately Second Lieutenant Edward Miller-Mundy’s troop of the 12/Lancers arrived in Nieuport at 9.30am just before the first German units arrived. Yet it was a touch-and-go for a while. Smith and his sappers arrived at the Dixmuide-Furnes road bridge in time to assist Second Lieutenant Edward Mann whose drawn revolver was enough to persuade the Belgian sapper officer the bridge needed to be destroyed:

‘He finally pressed the switch but there was no result; 2/Lt Mann then inspected the charges on the bridge, which had obviously been tampered with, and on his return found a French major, who told him he would now take command, that his troops were fast approaching and 2/Lt Mann need bother no more about blowing the bridge.’2

Smith’s account states that the ‘bridge was completely destroyed in spite of the two [sic] Belgian officers who said that the bridge was to be blown on their instruction’. He makes no mention of the French officer who Mann says attempted to take command but goes on to say, ‘The destruction had only just been completed when German motorcyclists arrived at high speed closely followed by infantry in lorries and it seems certain they hardly expected the kind of reception they received.’3

It appears that the German infantry anticipated the bridge to be intact and the barrage of fire they received on arrival was not in the ‘French’ major’s plan as he had by now melted away leaving the Lancers to deal with the enemy infantry. Smith writes these were soon seen off and he then left for Schoorbakke to destroy another bridge before moving to Nieuport to give assistance to Second Lieutenant Henderson’s troop who were struggling with the canal bridges. At 11.00am the first patrol of German motor cyclists from the 256th Division approached Nieuport along the coast road – sandwiched between refugees – and were swiftly dealt with by the Lancers in a ‘short and intense fire fight’. The Lancers’ war diary records that soon afterwards reinforcements in the form of 100 gunners and engineers of Adam Force, took over the line. For the time being the eastern end of the perimeter was intact.

The precarious nature of the line is illustrated by the defence that was assembled between Wulpen and Nieuport, a sector under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Edward Brazier. It was hardly an ideal position but despite the ground resembling a ‘chequer-board of dykes and ditches, crossed only by occasional bridges’, the difficulties faced by the defenders were also faced by the attacking infantry. Brazier was not alone in giving thanks that the ground did not favour tanks. Close to the bridge at Wulpen Lieutenant Beasley, a gunner officer from 210 Battery, 53/Medium Regiment, found himself turned into a front-line infantryman:

‘The Germans arrived the following morning and shelled and mortared us heavily. This was our first taste of real war and the casualties in our mixed force were pretty heavy. The regiment was pretty lucky on the whole but lost a lot of young boys and we were all stunned to hear that [Lieutenant] Bruce Thornton had been killed trying to rescue a Bren from an impossibly exposed position ... The Boche threw out strong patrols over the bridge and it was decided to send out a party to blow the bridge (the gunners had already tried with their 25-pounders but had not been successful). A young sapper officer volunteered to take a small party but he was unlucky enough to meet a German patrol on the bridge. He managed to get away after a scuffle but the party suffered some casualties and the bridge remained ... On the second day this cosmopolitan force was relieved by the 2 Battalion Royal Fusiliers [12 Brigade]. We felt pretty embarrassed at handing over a folorn task to infantry who had been marching and fighting for five days without any sleep, well knowing that they had come so that we, amongst others, could get away – a rotten mission to give anyone.’4

Edward Brazier and the men of ‘Brazier Force’ were taken off the beaches at La Panne on 30 May.

Although not part of Brazier Force, Mark Henniker, who by this time had been promoted to command 253/Field Company, was amongst several RE units sent up to Furnes to bolster the line. Arriving in the town square he was surprised to find himself in command of nearly 1,000 officers and men and, as he later observed, they were hardly organised or trained for an infantry battle:

‘There were men and vehicles from the other two Field Companies of 3 Division, and the more cumbersome vehicles of the Field Park Company. The OC 17 Field Company was a regular officer and senior to me, but it was reported he had been killed that afternoon. The OC of 246 Field Company was also a regular and senior to me but out on a reconnasiance somewhere and the OC 15 Field Park Company was only a captain, so I was evidently the Head Boy of all those present.’5

Captain Dick Walker, the 3rd Division RE adjutant, lost little time in sending the engineer detachments up to Coxyde (Koksijde) at great speed where they were deployed along the canal and ordered to hold until the arrival of Brigadier Christopher Woolner’s 8 Brigade. Here they were tucked in alongside the 1/ Suffolks who were, by this time, without Lieutenant Hugh Taylor who had been a casualty of the 8 Brigade attack of 23 May at Watrelos on the Gort Line. Henniker’s concern that his engineers would not live up to expectation was soon dispelled by the Suffolks’ adjutant who praised their soldierly behaviour under fire, leaving Lieutenant Colonel Desmond Harrison to proclaim that ‘Morale was beginning to drop a bit, but Henniker and 253 sat like a rock in the brigade reserve line and did a lot of saving the day.’

Also approaching Furnes at the end of a 15-mile march were two battalions of 7 Guards Brigade. The clatter of small arms fire and the presence of harassed staff officers was the first indication that part of the town was already in enemy hands, an observation Guardsman George Jones of 1/Grenadiers had already made for himself. ‘About a mile away and out of range as far as we were concerned, a party of Germans could be seen marching and wheeling bicycles at about the same speed as us. Friend and foe arrived in Furnes at about the same time.’ Despite the enemy presence and ‘rather annoying sniper fire’ the Grenadiers moved up to reconnoitre their allocated positions. But it was here that tragedy struck the 2nd Battalion when Lieutenant Colonel John Lloyd and two of his company commanders, Captain Christopher Jeffreys and Major Hercules Pakenham, fell victim to German sniper fire. The three officers were lying in a very exposed position on the canal bank, the colonel was obviously dead but Pakenham and Jeffreys were still alive and it was probably their plight that drove Lieutenant Jack Jones to drag their bodies to safety.6 Command of the battalion fell on the broad shoulders of Major Rupert Colvin who eventually led the battalion home via the beaches at La Panne.

Thus on 28 May Montgomery’s 3rd Division was moving into the Furnes salient with 8 Brigade to the north and 9 Brigade to the south and – sandwiched in between – were the two Grenadier battalions of 7 Guards Brigade holding the centre and southern outskirts of Furnes. The 1/Coldstream arrived during the night of 29 May and was placed in reserve on the Coxyde road. What followed was a messy and sustained battle characterized by almost continuous shell fire that systematically destroyed the buildings of Furnes and causing George Jones to remark that ‘We saw the town of Furnes tumble about us. The Germans expended untold quantities of ammunition upon the area, and us!’

But shellfire and sniping were not the only dangers. On the night of 30 May enemy infantry attempted to cross the canal using inflatable rafts and pontoon bridges resulting in a fire fight that drew in the 1/Coldstream Guards. Here an enemy foothold on the northern bank was counter-attacked by 35-year-old Major John Campbell, commanding 1 Company. ‘He and his runner went forward with grenades under cover of fire from one of his platoons, to dislodge the enemy. He silenced one machine-gun and damaged one pontoon, but as he was attempting to rush another enemy post he was fatally shot and his runner was wounded.’7 The news of this may well have contributed to the death of Campbell’s father, Brigadier General John Campbell had been awarded the VC at Ginchy in October 1916 whilst commanding 3/Coldstream.

Support from 3 Company managed to staunch any further incursions but the determination of the enemy to force a crossing cut down almost all the company officers leaving 21-yearold Second Lieutenant Peter Allix and Captain Cecil Preston dead on the canal bank. The Coldstream counter-attack had taken place in the nick of time: dawn revealed the enemy outpost had withdrawn which enabled British mortars and artillery to target the enemy pontoons, persuading the Germans to cease in their efforts to cross the canal.

The focus of the enemy assault next day fell on 8 Brigade which was already running short of ammunition and for a while it looked as if the enemy would manage to encircle the salient. Rallied by Lieutenant Jack Jones and his carrier platoon, resistance was stiffened and the line restored. Jones was awarded the MC for his ‘prompt and determined actions that undoubtedly saved a situation that would otherwise have had disasterous results’. But it was only a matter of time before the enemy broke through what had become a very thin line of defence. Fortunately the orders to retire to La Panne came at exactly the right moment and in the early hours of 1 June the brigade slipped away without further mishap, reaching La Panne around 3.00am. George Jones remembered it well:

‘For us the miracle of Dunkirk then began. This curtain of ragged steel began to lift just before 10.00pm and, in the bright red glow of a hundred fires, we walked from Furnes without a bomb, shell or bullet arriving within half a mile of our scrambling single files. Twice we took wrong turnings almost walking down the throat of the enemy ... but at last we were clear.’8

On 27 May the 1/Duke of Wellington’s Regiment from 3 Brigade was on its way to Dunkirk when they were diverted to Les Moëres, just south of Bray-Dunes, and ordered to hold a 5,000 yard sector of the Canal de Basse Colme between the bridge at la Cartonnerie and the bridge carrying the D79 at Pont Pauwkens Werf. With battalion HQ at a farmhouse in les Moëres, C Company, under Captain William Waller positioned itself astride the bridge at la Cartonnerie, leaving A and B Companies to hold the remaining canal bank. As the regimental historian points out, the front may have been protected by the canal but the field of fire was in places less than 30 yards, as the D3 running along the southern bank was packed with abandoned vehicles and, in the case of C Company, a number of residential buildings.

Abandoned vehicles were also causing problems for the men of 2/Coldstream who had taken up positions on the Dukes’ right flank. The difficulty posed by the tangle of immobilized trucks and lorries was that they afforded cover to the approaching Germans and made it possible for their infantry to get close to the canal bank almost completely unobserved. Nevertheless, Bootle-Wilbraham deployed his Coldstreams along the northern bank to await the arrival of the enemy:

‘We had a front of 2,200 yards to cover, with two important bridges over the canal. No. 1 Company was on the right, No. 3 Company right centre, No. 2 Company left centre and No. 4 Company on the left. Headquarters was badly placed in a little farmhouse to the south of the windmill at Krommelhoeck. The mill was used as an OP and was an obvious landmark in this flat, open country. The canal was a reasonable anti-tank obstacle; a second canal, called Digue des Glaises, ran parallel to the front, about 400 yards behind it, and there was yet another canal behind battalion headquarters by the windmill.’9

Dawn on Thursday 30 May saw water in the canals gradually rising as the open sluices slowly flooded the surrounding countryside. Concerned that the floodwaters would channel the Germans towards the bridges, Bootle-Wilbraham ordered the bridges on his front to be blown, the Dukes following suit at 11.00am at Pont aux Cerfs. Apart from some heavy shelling and ‘a great deal of small arms fire’ there was no serious assault during the day, the Dukes reporting that ‘the Germans who reached the banks of the canal did not return to tell the tale’.

Commanding 3 Company of the Coldstream was 35-year-old Major Angus McCorquodale, a larger than life figure whose brother Hugh had married the novelist Barbara Cartland in 1936. The only other officer in the company was Lieutenant Jimmy Langley whose reponse to Brigadier Merton Beckwith-Smith’s ‘absolutely splendid’ news that the battalion had been given the ‘supreme honour’ of being the rearguard was muted to say the least. Suggesting the brigadier should inform the men of the ‘splendid news’ himself, he listened quietly as ‘Becky’ told them that not only were they about to fight one last battle, but also how they should deal with Stuka dive bombers with a Bren gun, ‘taking them like a high pheasant and giving them plenty of lead’.

McCorquodale based his company HQ in a small cottage on the banks of the canal east of le Mille Brugge and while the company dug their weapons pits a continuous stream of British and French troops crossed the canal watched by Jimmy Langley:

‘They varied from two platoons of Welsh Guards, who had been fighting near Arras – though they looked as though they had performed nothing more arduous than a day’s peace time manoevering – to a bedraggled, leaderless rabble. I also came across some outstanding individuals. One corporal in the East Kents, particularly excited my imagination. Barely five feet tall, wearing socks, boots and trousers held up by string, he had a Bren gun slung on each shoulder with a rifle slung across their barrels. The slings of the Bren guns had cut deep into his shoulders, his back and chest were caked in blood and I could see part of both his collar bones. I offered him a mug of tea and ordered him to drop the Bren guns as I would be needing them.’10

Resolutely holding onto his guns the corporal explained that his major, who was ‘dead somewhere back there’ had told him to get both weapons back to England as they will be needed soon. Looking Langley straight in the eye he made it quite clear that that was exactly what he intended to do. Langley’s reply was to put a generous tot of whiskey in the man’s tea, patch him up and send him on his way.

The 1 June – ‘a glorious day’ wrote Bootle-Wilbraham – began with a ground mist which lifted as the sun rose. To Langley’s astonishment it revealed a hundred or so Germans ‘standing in groups about 600 yards away in a field of corn’. Opening fire on the mass of enemy soldiers in front of them resulted in, what Langley called, a massacre leaving him feeling slightly sick; a sensation which was quickly forgotten with the enemy attack on the area of the blown bridge at le Mille Brugge. Langley was observing from the attic in the cottage:

‘This was partially held by No.1 Company, under Evan Gibbs, on our right, and partially by a company of a regiment from the North of England, the road leading back from the bridgehead to Dunkirk being the boundary line ... We had seen the Germans rush up what looked like an anti-tank gun on wheels and watched with interest as it pointed our way and fired. Nothing happened and we turned a Bren gun onto it. Then there was the most awful crash and a brightly lit object whizzed round the attic, finally coming to rest at the foot of the chimney stack. One glance was enough – it was an incendiary tank shell ... The Germans put four more shells into the attic and then desisted.’11

The enemy assault was enough to encourage the 5/Border Regiment on the right of Captain Evan Gibbs’ company to contemplate withdrawing, a notion that was greeted by McCorquodale’s threat to shoot them! The Borders’ war diary simply states that on 31 May all ranks that were considered non-essential were ordered to withdraw to the beaches and A and C Companies came under heavy shellfire. Sadly war diaries are notorious for reporting the facts as seen by a particular battalion and there is no mention of why they withdrew or who gave the orders. One can only assume that their move – which opened a gap in the line on the Coldstreams’ right flank – was sanctioned by the CO, Lieutenant Colonel Law.

By now it was clear the enemy were massing for an attack which the defending troops would have little chance of holding – rather, it was merely a question of how long they could contain it before being overwhelmed. Evan Gibbs was killed attempting to retrieve a Bren gun leaving an inexperienced Lieutenant Ronnie Speed in command. McCorquodale sent Langley with a flask of alcohol with orders to make Speed drink it and shoot him if he retired the company. ‘Ronnie was looking miserable, standing in a ditch up to his waist in water and shivering. I offered him Angus’s flask and advised him to drink it, which he did.’ Half an hour later Speed was killed and the remaining men of 1 Company fell back on Langley’s cottage.

The end came shortly afterwards. McCorquodale – determined not to die in the new British battledress which he abhorred – had changed into his First World War service dress – while Langley was dealing with a German machine gun firing from a cottage on the opposite side of the canal:

‘I started my favourite sport of sniping with a rifle at anything that moved. I had just fired five most satisfactory shots and, convinced I had chalked up another ‘kill’, was kneeling, pushing another clip into the rifle, when there was the most frightful crash and a great wave of heat, dust and debris knocked me over. A shell had burst on the roof. There was a long silence and I heard a small voice saying, ‘I’ve been hit,’ which I suddenly realized was mine.’12

Langley had been hit in the head and left arm and was soon after evacuated to Dunkirk but being a stretcher case was refused access to a boat on the grounds that he was unable to sit or stand up. Returned to the care of 28-year-old Captain Phillip Newman at 12/Casualty Clearing Centre, he was taken to Château Cocquelle in Rosendael to await the arrival of German troops.

News of the German assault on the canal was received by Bootle-Wilbraham with some sadness; there is little doubt he apportions the demise of two of his companies on the withdrawal of the 5/Border Regiment:

‘The Germans had outflanked No.1 Company, having got across the canal where our neighbours had abandoned their positions. The three officers of the company had been killed – Evan, Charles Blackwell and Ronnie Speed. The warrant officers and senior NCOs had been killed, including PSM Dance and Sgt Hardwick who had done so well at Pecq; and then the leaderless company had been forced back on to No. 3 Company. Angus had been killed when his bit of trench was enfiladed. Jimmy Langley put up a magnificent fight in a cottage on the canal bank and continued to fire his Bren until he was put out of action. It was Nos. 1 and 3 Companies that bore the brunt of the attack. Nos. 2 and 4 Companies had a comparatively easy time and few casualties. Jack Bowman brought out the remainder of the much reduced right half of the battalion ... The battalion was allowed to slip away in the darkness, and they were not followed up. There was no moon.’13

Both the Dukes and the 2/Coldstream were evacuated from the Dunkirk Mole late on 2 June joining the 6,695 British troops who finally left France that day. Over the course of the short campaign the 2/Coldstream had sustained 195 casualties of whom 70 officers and men had been killed.

A little to the east of the small tributary which joins the Canal de la Basse Colme near the bridge at le Benkies Mille was the ground defended by 1/East Lancashires. On 31 May Second Lieutenant John Arrigo and his platoon from D Company were in position around the destroyed bridge and reported being under fire from snipers, two of his men being shot and killed near the bridge during the morning. The battalion had initially been allocated a 3,000 yard frontage to defend which Lieutenant Colonel Pendlebury realized immediately was an almost impossible task given the depleted strength of his men and their lack of fire power. We shall never know whether Pendlebury’s decision to replace D Company with the Stonyhurst-educated Captain Marcus Ervine-Andrews and B Company was a purely tactical judgment, or was motivated by the fighting spirit already displayed by Ervine-Andrews. But whatever the reason the move set the scene for the award of the final Victoria Cross of the campaign.

Ervine-Andrews had C Company of the 2/Warwicks under Captain Charles Nicholson on his right, whom the reader will recall had avoided the Wormhout fighting being ordered to Bergues on 27 May. On his left were the 5/Border who at least reduced the East Lancashire’s frontage to a more reasonable defensive line. Dawn on 1 June began with a crash of explosions and Ervine-Andrews recalled that:

‘There was a tremendous barrage of artillery and mortaring throughout the first attack. It must have gone on for two to three hours ... During the course of the morning most of my four positions were pretty all right – the odd casualty here and there, but one position was in desperate straits. They were running very short of ammunition and were forced to search the dead bodies to find some more ... They now asked for urgent help. I had no reserves whatever. I picked up my rifle and some ammunition and, looking at the few soldiers with me in company headquarters, said “I’m going up. Who’s coming with me?” Every single man came forward.’ 14

The section in trouble was fighting from a barn close to the junction of canals. When Ervine-Andrews and his men arrived the roof was ablaze and the enemy were attempting to cross the canal using inflatables:

‘My men didn’t fire much because we were too short of ammunition. They realized it was better that I should do the firing rather than waste the few bullets we had. If you fire accurately and hit men, then the others get discouraged. It’s when you fire a lot of ammunition and don’t do any damage that the other chaps start being very brave and push on. When they’re suffering severe casualties they are inclined to stop or, in this case, move round to the flanks.’15

Holding off the attack Ervine-Andrews personally accounted for seventeen Germans with his rifle and several more with Bren gun fire. At 3.00pm he sent his second-in-command, Lieutenant Joe Cêtre, to battalion HQ to report on the situation and Cêtre returned with a fresh supply of ammunition and a handful of reinforcements along with instructions from Pendlebury to hold the position until the last round. Incredibly they did and it was early evening when the survivors withdrew. But the story does not end there; left with two badly wounded men Ervine-Andrews assigned the one remaining carrier to transport them to safety leaving himself and eight men to reach the beaches on foot. They arrived at their evacuation point on 3 June and were taken off by HMS Shikhari on one of the ship’s last evacuation runs.

The announcement of Ervine-Andrew’s award of the VC – the seventh to be awarded to former Stonyhurst pupils – came as a surprise to the 28-year-old captain who considered the fight to have been a company action and always maintained that ‘Anything that I was able to achieve was made possible by the support and bravery of my men.’

Another kind of bravery was exhibited by Lieutenant Richard Doll who had left Aldershot with the 1/Loyal Regiment on 22 December 1939. Appointed as the medical officer to the battalion, Doll’s war in 1940 was very much governed by the movements of 2 Brigade which, on 29 May, was ordered to take up a position east of Bray-Dunes in preparation for evacuation. Lieutenant Colonel John Sandie was probably more aware of the overall situation along the Dunkirk perimeter line than his battalion was, but even so, the order to turn round and march back towards the enemy was not greeted with enthusiasm. Richard Doll recalled the moment:

‘During the previous night fifty of the battalion had been allowed to go down to the beach and embark, so we were expecting to get off at any minute. However, we were to be disappointed, for we were suddenly ordered forward to Bergues where we were told the Germans had broken through. The adjutant borrowed four lorries from an artillery regiment and sent off D Company to hold the canal in front of Dunkirk while the rest set off the seven miles on foot.’16

Doll was convinced that the battalion had been tricked into relieving the Bergues garrison whom he says consisted of a mixed force of stragglers from the Lincolnshires, Welsh Guards and Royal West Kents together with ‘a reliable French battalion with an able commander’. He records his anger at finding a number of British officers ‘feasting off roast chicken and champagne in a large and beautifully furnished house’ who were apparently delighted at seeing their relieving force arrive and left the town an hour or so later. Harsh words indeed from a junior officer but, in the circumstances, perhaps understandable.

Clearly the Germans had not broken through and although Doll’s rather emotive view of the situation may have been shared by others, the 470 officers and men of the battalion who entered Bergues were welcomed by Major General Curtis to reinforce the 46th Division units deployed in and around the town. In 1940 Bergues was an old country town built on the side of a hill at the junction of three canals and was entirely surrounded by the 17th century ramparts which were pierced by four gates. It was around these gates that Sandie deployed the Loyals and together with the remaining troops who had been formed into companies by Captain Arthur Walch, they constituted a rather chaotic defence.

During the night of 30 May Bergues was shelled and the 2/5 Sherwood Foresters, who were to the east of Hoymille, came under severe artillery and mortar attack which ultimately forced them back behind the Canal des Moëres. Enemy shelling continued throughout the next day, Private Hector Morgan in D Company near the Ypres Gate recalled how:

‘We were jumping from door to door. The German gunners were dropping shell after shell and as soon as they had dropped one, off we’d go into another doorway. It so happened that I was flattening myself in one of the doorways when he [the Germans] dropped one about fifty yards from us. All of a sudden I felt this terrible bash on my back and I said to one of my mates, that’s my lot. I’ve had it.’17

Morgan lived to tell another tale as the projectile that had hit him was a large cobblestone thrown up by the explosion but there were many other casualties, Richard Doll reported a continual stream of wounded pouring into the cellar where he had established his RAP: by midday it was overflowing.

By daybreak on 1 June fires had taken hold near the church and town hall and whole rows of residential buildings were in flames. The heat was so intense that even the troops dug in around the ramparts were feeling its effects while terrified horses galloped up and down the streets into which debris from burning buildings was falling. Casualties were mounting steadily: one shell alone accounted for nine men killed and two officers and another fifteen men wounded. At midday Curtis ordered the Loyals to evacuate the burning town and take up positions along the canal outside the northern ramparts.

At 1.50pm news reached Sandie that the Germans had forced passage across the canal – this was the action involving the Coldstream and the 5/ Border which also overwhelmed one platoon of the 2/Warwicks – and enemy units were reported to be advancing north. Two companies of the Loyals were ordered north to counter-attack leaving D Company to oversee the last British units leaving the town. For Richard Doll the evacuation from Bergues was far from straightforward. Finding the town almost deserted he was determined not to leave the wounded behind:

‘I sent Stansfield (my driver) to get the 30cwt lorry and filled it with all the able bodied men and those of the wounded who could fire. I removed the hospital tags from them as, if they were to fight, they could not claim to be wounded. Each was armed with a rifle ... A difficulty soon arose, for the town was so shattered that we were unable to recognize our way about. We made one false attempt to get out, being halted by a blown-up bridge, when to our delight we found a soldier who was apparently still on duty; he turned out to be a Royal Engineer who was dealing with the last bridge, and he redirected us to it. Once again we lost our way, and following a dispatch rider, we came out near the crest of the hill well in sight of the enemy. We turned round at full speed and tore back over heaps of bricks and rubble into the town; two shells must have landed very near us, for twice the car was shaken as loud explosions seemed to crash above us. This time I was luckier, for I took the right turning and saw Captain Leschalles, D Company commander, and I breathed a sigh of relief.’18

Doll’s journey to Dunkirk was accompanied by a cacophony of enemy shellfire which periodically sent him and whoever was with him at the time scuttling into drainage ditches to seek shelter. Eventually he and half the battalion were taken off the beaches at Malo les Bains aboard the SS Maid of Kent. The other half of the battalion was not so lucky; they marched out along the mole but missed the last boat and had to spend all Sunday on the beach before getting away on 3 June.

Frustrated by the inactivity that presented itself at Bray-Dunes, Major Mark Henniker found two beached rowing boats with Teddington painted on the transom. Stocking them with food and water he and his group of two officers and thirty men hauled the two boats into the water and began to row towards England. Having swapped boats en-route and collected three more men who were drifting aimlessly without oars, they waited for the tide to turn in their favour, which it did early the next morning:

‘After we had been rowing for about two hours we were out of sight of land. We then saw what I took to be a Royal Naval pinnace pointing towards us. The sea was like glass and, as we got closer, it seemed to be stationary or moving very slowly, for she had no bow wave ... We rowed towards her and found she was deserted, so we tied up astern and boarded her, there was a half eaten meal on a table and food and water in plenty aboard. A lieutenant commander’s jacket was hanging on the back of the stateroom door with his name on the tailor’s tab in the back.’19

They had come across their own Marie Celeste and while there was plenty of evidence on the boat from what looked like an air attack, the crew had completely vanished. Henniker writes that they soon got the boat moving and were eventually taken aboard HMS Locust just before reaching Dover.

But for thousands of men like Private Bill Holmes of 4/Royal Sussex who had marched out of Caëstre to Mont de Cats in the early hours of 28 May, their arrival at Dunkirk was too late. Joining the hopeless groups of tired and hungry men now stranded on the beach Holmes and his mates stared across the water towards England as if willing a ship to appear:

‘Then before we knew what was happening, several of these German motorcycle combinations arrived. They fired traced bullets at us, so we had no choice. You either gave up or died. I never thought I’d ever be a prisoner. I thought I might be killed. But one thing I thought was if I’m going to die I’d like to die at home. I didn’t mind being shot but I didn’t want to die out there. I was a long way from home.’20

Holmes and those like him who had been left behind were destined to face an uncertain future behind the wire of captivity which for many would last for five years.