Under the apple tree Anatole stopped swinging. There, on a garbage pail in the alley, sat a tall blond man in a tattered blue uniform, eating an apple and cocking his head to hear Anatole’s mother as she practiced “Awake, Ye Wintry Earth” in an uncertain alto for the Sunday service.

So of course Anatole walked right up to the garbage pail and waited for the man to speak.

But the stranger went right on eating his apple.

“Who are you?” demanded Anatole.

The stranger shook his head. “Don’t know. Woke up this morning to find I’d been robbed of everything I had. Name, address, destination.”

Anatole was so surprised that for a moment he could think of nothing to say. Still, he wanted to help.

“Did you check your pockets?” he inquired.

“What do you know about that!” The man slapped his knee. “Forgot to check my pockets.”

He rummaged through his pockets and pulled out a large tooth.

“It once belonged to a reindeer,” he said. “I carry it for luck.”

As soon as he saw the tooth, Anatole wanted to trade his rabbit’s foot for it, but the stranger was already tucking it carefully out of sight. Then he tried another pocket and found a tiny folder, cut like a canister, on which was printed in gold the following inscription:

Van Houten’s Cocoa, on the tables of the world.

A Perfect Beverage

combining Strength,

Purity, and Solubility.

Open here.

When he opened it, up popped a little paper table set for two: two painted plates, two cups of painted cocoa, two painted sugar buns.

“Very tasty,” said the stranger. “Instant breakfast. Want some?”

“No thanks,” said Anatole. “I’ve already eaten mine.”

“Put it in your pocket then,” said the stranger. “Pockets are a great invention. Did you know my mother was a kangaroo? Perhaps the earth is but a—” He waved his arms histrionically, searching for the word.

“A marble?” suggested Anatole.

“A marble, right! A marble in the pocket of God. When I was a kid, I used to pick pockets in reverse. Instead of taking things out, I put things in. A gumdrop here. A candy cane there. Now how did this ad for Van Houten’s cocoa get in my pocket?”

“Maybe you’re a traveling salesman,” said Anatole.

But the stranger was rummaging through his pockets again. This time he pulled out a silver Maltese cross.

“Now what in the name of heaven is this?” he exclaimed.

“That’s a war medal,” said Anatole. “Oh, let me look at it. I’m very interested in war. There’s writing on the back. E-R-I-K H-A-N-S-O-N.”

“Erik Hanson!” shouted the stranger. “Why, I’m Erik Hanson of the 147th Regiment. That’s two things I remember.”

“Four,” said Anatole. “Your mother is a kangaroo and you put things in people’s pockets.”

“I forgot to tell you—what is your name?”

“Anatole.”

“Well, Anatole, I forgot to tell you I’m an awful liar and you can’t believe half of what I say. But what army did I serve with, I wonder?”

“Wait right here,” said Anatole.

He darted into his house, pulled all the galoshes out of the hall closet, and—wonder of wonders!—there lay his shoebox of lead soldiers, just where he remembered putting it away. Then he ran into the bathroom and grabbed a book that was lying on the radiator. At night in the bathtub he liked to read a chapter from So You Want to Be a Magician. And finally he raced back to Erik Hanson, half afraid he would find him gone.

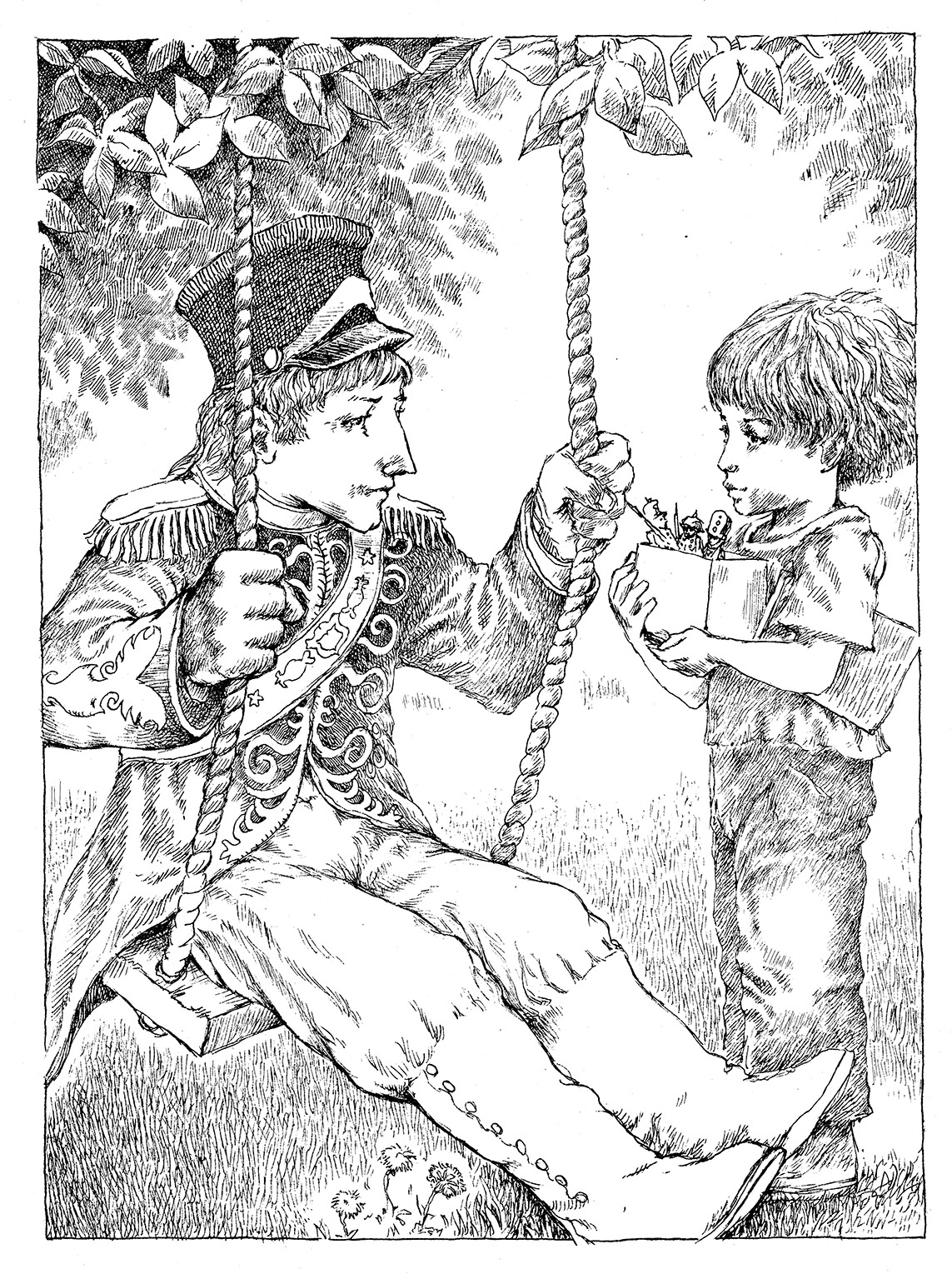

But there he sat, swinging to and fro on Anatole’s swing, dragging his feet in the dandelions. Anatole opened the box of soldiers to show him, and Erik peered in, very much interested.

“You have a fine collection. I had a wooden soldier when I was a kid. And if you opened him up, you found another one, only smaller. And if you opened him up, you found another one, still smaller. The smallest was no bigger than a flea’s ear. I never saw it, but I knew it was there. Some things you have to take on faith. Well, Anatole, do you find anyone like me in that box?”

“Here’s a soldier in a blue uniform rather like yours,” said Anatole, picking one out. “Maybe you’re an infantry corporal of the U.S. Army, 1864.”

“That would make me awfully old,” said Erik, laughing. “Over a hundred.”

“How old are you?” asked Anatole.

“BUT THERE HE SAT, SWINGING TO AND FRO ON ANATOLE’S SWING, DRAGGING HIS FEET ON THE DANDELIONS.”

Erik shrugged. His rough pink skin wrinkled merrily around his eyes. His hair was so pale that you could not tell whether to call it blond or white. He might have been twenty; he might have been fifty.

“I brought out my magic book, too,” said Anatole. “It tells how to find things like coins and playing cards. And it’s full of nifty magic words. Abracadabra! Puziel, guziel, psdiel, zap!”

“See if there’s a chapter on finding lost people,” said Erik.

Anatole opened the book.

“Darn it, this isn’t my book of magic. It’s my book of games.”

“Oh, I love games,” exclaimed Erik. “What games does your book have?”

“Fox and Goose,” read Anatole, flipping through the pages, “Bob-Cherry, Baste the Bear, May I, The Quickest Way of Going to Anywhere . . .”

“What is the quickest way?” asked Erik. “I don’t know that game.”

So Anatole read:

“Let the players write the name of London Town (or the desired destination) on a paper and cast it into the middle of the circle. Then, let them take hands and run around the circle very fast, chanting:

“ ‘See saw sacradown,

which is the way to London Town?

(Insert desired destination.)

One foot up and the other foot down,

that is the way to London Town.

(One journey to a customer.)’ ”

“That sounds like a magic spell,” said Erik. “Ahoy, boys, I’m off to Hawaii!”

“No, it’s not a magic spell. It doesn’t have any magic words.”

“Nonsense,” said Erik. “You know why those words don’t sound magic? Because we know what they mean. Now if I were a one-eyed bull snake and heard those words, I’d figure they were the most magical things around. Let’s write the name of my town on a piece of paper, and then let’s draw a circle . . .”

“You don’t remember the name of your town,” Anatole reminded him.

“Quite true. I forgot. So let’s write. ‘Erik’s home.’”

Anatole ran once more to the house and fetched paper and pencil from the kitchen table and wrote very carefully:

Erik’s Home

Under the apple tree, Anatole drew a circle in the grass with his heel and cast down the paper.

“Now, let’s take hands,” said Erik, “and start running.”

And as they ran, they shouted:

“See saw sacradown,

which is the way to Erik’s home?

One foot up and the other foot down,

that is the way to Erik’s home.”

Almost immediately their feet left the ground and sped effortlessly over the tops of the trees and then over the clouds. Anatole found it amazing that his feet, so long accustomed to the ground, could make a road of the air. Through a break in the clouds, Anatole saw the Statue of Liberty. And then he found himself running beside Erik over the open sea.

Waves heaped themselves up and tumbled toward them like mountains, on which the sun shone so brilliantly that you would have thought they were running on silver.

“Look,” called Erik, “a boat! Let’s give them a scare, shall we?”

An ocean liner was passing them, slowly and steadily, and they ran alongside it so close that Anatole could see men and women dancing in the main ballroom, and he could hear the orchestra playing “Blue Moon.” Through a porthole he could look into the kitchen, where two waiters were clinking glasses. The cozy smell of tobacco and cabbage nearly made him cry.

At the back of the ship huddled several passengers in blankets. A child’s voice cried out, “I see a man and a boy running on the sea!”

And the grownups all looked up at the broken clouds of the evening sky, for of course that is the reasonable place to find the unexpected shapes of things.

Night came swiftly and swallowed the ship, but a thin crack of light broke on the horizon ahead of them. Then the sun popped up like a luminous peach, silhouetting a fishing boat where three old men rowed toward a distant shore.

“Hey, fishermen,” called Erik, “what country is that?”

“Norway,” called back the fishermen, who had seen stranger sights in the sea than a man and a boy running on the water. They had not run very long before Anatole spied a ferryboat ahead of them, and as they drew near, they heard childish voices singing:

“Ja, vi elsker dette landet

Yes, we love this land of ours . . .”

There on the main deck stood a stout man in uniform, directing a chorus of school children.

“Hey, schoolmaster,” called Erik, “what town is that?”

The schoolmaster was too astonished to answer, but the children cried out joyously, “Fredrikstad, Fredrikstad.”

At these words, Anatole felt his feet turn abruptly. Now they carried him over a town of small wooden houses, past a brickyard, and then suddenly his feet stopped, and Anatole tumbled into a new-mown pasture, and Erik tumbled on top of him.

Anatole sat up.

“Erik, where are we?”

Erik’s face looked as if the sun had just risen in it.

“In Sellebak. And you won’t find it in the World Atlas, either. What nerve to call itself a World Atlas and not include Sellebak! Do you see that house at the edge of the pasture? I was born in that house. Do you see that tall man standing in the doorway? That’s my father. He sailed all over the world when I was little. He’s bald as a stone now; he wasn’t then. And that small woman beside him, she’s my mother. Her hands are tinier than yours, Anatole. I used to play with her gloves in church. Oh, Anatole, I remember, I remember!”

By nightfall, everyone in Sellebak knew that Erik Hanson had returned, bringing with him a boy who was rumored to be a great magician. Friends came all the way from Fredrikstad to see him. To make certain of a warm welcome, each one brought something to eat, until Fru Hanson’s kitchen could hold no more baskets of cheese, no more platters of herring and onions and fish cakes, and no more jars of cloudberry jam. Herr Hanson set up a table outside, a safe distance from the gooseberry bushes that were just ripening and a great temptation to the children. Only Anatole noticed the old man who stood by the biggest bush eating gooseberries, as if he thought himself invisible or everyone else blind. He did not seem to belong to any of the visiting families.

Over a bowl of steaming cabbage, Erik remembered part of his story.

“You were eighteen and you enlisted,” said his mother, “and I never saw you again. It was a beautiful sunny day in June, just like this one.”

“I remember,” said Erik. “And I remember growing up in this house. I remember the stove where I loved to warm myself. It had a picture of Vulcan on the door.”

“I still have that stove,” said his mother, wiping her glasses and blowing her nose.

“And I remember the winter that the hens froze on their perch,” said Erik. “And I remember how I loved molasses on brown bread, and you told me how sugar and butter on white bread tasted much better, only there wasn’t any.”

“That was at the beginning of the war,” said Herr Hanson. “Do you remember the peaches I used to send you from America? Tell me, Anatole, do you like peaches?”

“Yes, indeed,” said Anatole, taking a second helping of fish cakes.

“Good,” said Herr Hanson. “Shows you have good sense. Magic is fine, but I don’t understand it. I think perhaps Erik is not quite right in his head; all these stories about running across the ocean. Well, well. We must believe in God and accept what happens.”

A stout young woman with a crown of blond braids on her head and a child in her arms came shyly up to Erik.

“Do you remember me, Erik? You promised to marry me once. Well, that was a long time ago, and I married another man. But I still remember the song you sang to me.”

And the whole company fell silent as she sang, slowly and clearly:

“How lovely is your golden hair,

blessed is he who can win you.”

The sun danced in the leaves of the plum tree, and Fru Hanson wiped her glasses.

“That was thirty years ago,” said Erik. “I remember all of you. I remember the day I went off to fight. But of that thirty years between that day and this, I remember nothing.”

He stood up and walked around the yard, whispering, “Thirty years lost! Thirty years lost! What I wouldn’t give to see them again!”

And Anatole, stumbling after him, bumped smack into the old man who was still helping himself to the ripe gooseberries.

“Excuse me,” said Anatole.

“So you wish to turn back the sun,” called the old man to Erik. “Then it’s to the sun you must go, my lad. My great-grandfather journeyed there once.”

“Is it possible?” exclaimed Erik.

“Not for you,” said the old man, laughing. “The sun speaks only to children. If anyone can find the sun’s house, it’s this boy here. But the way is long and very difficult.”

“Very difficult?” asked Anatole, who loved a good adventure if it was not too dangerous.

“Of course,” said the old man, “but there are always people who want to make the journey because there are always people who want to be magicians.”

“Can the sun make me into a magician?”

The old man shook his head. “The sun won’t, but the journey will. It’s the journeys we make for others that give us the power to change ourselves. The hardest part is getting home again, for you can’t go home the way you left it. Nobody can give you the magic to take you home. You have to find that magic on your own.”

“Oh, Anatole,” exclaimed Erik, “say you’ll go.”

“Of course you can always be an ordinary magician who pulls rabbits out of hats and doves out of handkerchiefs,” said the old man.

“No,” said Anatole, “I want to be a real magician. How do I find the house of the sun?”

The old man looked very pleased. “I will give you some runes to say.”

“Runes?” asked Anatole, puzzled. “What are runes?”

The old man smiled. “Runes are the magic words of the old gods who lived here before the Christians came.”

“I love magic words,” said Anatole.

“Yes, I could tell that at a glance. And so these words will probably disappoint you. They are perfectly clear, and yet they make no sense. They are important, yet they teach you nothing. Do you see that hill just beyond the pasture, across the road?”

“I see it. Erik and I landed near there.”

“If you stand on that hill and say the runes aloud, one of the four winds will come to help you. I don’t know which one. A fair wind is a great help in reaching the house of the sun. If you are in trouble, say the runes backward. But you can only use the runes in this way once.”

“Thirty years! I shall have my thirty years again!” crowed Erik.

“Tell me the runes,” begged Anatole.

The old man put his mouth close to Anatole’s ear so that Erik shouldn’t hear him.

“9 were Nothe’s sisters:

Then the 9 was 8

and the 8 was 7

and the 7 was 6

and the 6 was 5

and the 5 was 4

and the 4 was 3

and the 3 was 2

and the 2 was 1

and the 1 was none.”

“Who are Nothe’s sisters?” asked Anatole.

“They are the nine stars who bring in the night. They’re bringing it in now, though we can’t see it coming yet. Better hurry, for if the night catches you, you’ll never find your way home.”

“Good-bye, Erik,” said Anatole, beginning to feel a little anxious.

And to his amazement, Erik lifted him off the ground and kissed him.

“If I can help you, Anatole, call me. If you need a war fought or a field plowed—”

“I’ll come straight to you,” Anatole promised.

And he set off with great strides across the pasture for fear the smell of Fru Hanson’s savory pancakes would make him turn back.

The hill looked at him the way any hill at home would look at him; it said, Climb me. Anatole started to climb, stepping carefully in his sneakers over the slabs of stone that broke like wrinkled faces through the grass. When he reached the top, he saw he was standing where four pastures met. To the east and the south, he saw clusters of white houses dreaming on the horizon, with an uncertain road glinting between them. To the west sparkled a church as white and small as a tooth. To the north rose another hill.

Anatole stood on a rock and said gravely:

“9 were Nothe’s sisters:

Then the 9 was 8

and the 8 was 7

and the 7 was 6

and the 6 was 5

and the 5 was 4

and the 4 was 3

and the 3 was 2

and the 2 was 1

and the 1 was none.”

Nothing happened.

A flock of gulls fluttered down like handkerchiefs into the pasture. Then all at once Anatole spied a tiny speck in the sky that, as it flew nearer, took the shape first of a bird and then of an angel. But what, thought Anatole, could it be?

It was a man in a suit as white as snow and as bright as water, and he was riding a book, and when he saw Anatole, he sang out, “Who called the West Wind?”

“Me,” said Anatole, abashed at this strange figure. “I want to go to the house of the sun.”

“And what will you do when you find it?” asked the West Wind.

“I’ll ask the sun to give Erik Hanson his thirty lost years and to send me home again, for I can’t go home the way I came.”

The West Wind opened his book, which was the sad color of twilight, and turned the pages one by one. They gave off a most pleasant perfume, which Anatole saw came not from the paper but from the letters printed there. A castle and vineyard glowed in a sunlit D; the harvesters were carrying baskets of grapes on their heads, and Anatole could hear the women singing, though he could not understand the words. A formal garden grew in a shady O; the gardener tying back the delphiniums glanced up at Anatole and tipped his hat.

When the West Wind had turned every page, he closed the book, and the music stopped abruptly and the fragrance of the flowers disappeared.

“The house of the sun,” he said thoughtfully. “To tell you the truth, I don’t know the way, but I’ll take you to my brother the North Wind, who is stronger than I and flies farther.”

“IT WAS A MAN IN A SUIT AS WHITE AS SNOW AND AS BRIGHT AS WATER, AND HE WAS RIDING A BOOK . . .”

Together they flew north, over pine forests and over the camps of the Lapps following the reindeer and over the ice fields to the top of the world, and alit on the roof of the biggest palace Anatole had ever seen. A hundred turrets, he figured, and two hundred flags stiff as postcards; five hundred diamond windows at least, chimneys thick as a forest, and everything cut from blue ice.

“The door is always frozen shut,” said the West Wind. “We must fly down the great chimney.”

“What is the great chimney?” asked Anatole.

“Wait and see.”

Down the chimney they flew and crawled out of an ice fireplace into an enormous room. It had no furniture at all, nothing but a giant tree growing out of the floor to the ceiling. Perched on the lowest branch slept an eagle.

“Brother, wake up,” urged the West Wind. “This boy wants to find the house of the sun. Farewell!”

And the West Wind flew back up the chimney.

The North Wind opened his eyes. “You will find the house of the sun at the top of this tree.”

“How far is it to the top?” asked Anatole, who loved to climb trees.

“I do not know. But halfway up takes a hundred years. Are you a hero of the golden age?”

“I don’t think so,” said Anatole.

“Well, it’s worth finding out. Climb till you come to a golden city nestled in the branches of the tree. It belongs to the sun’s own finches, which sing to him day and night. Knock at the gate and ask for the magic drum that will carry you to the house of the sun. And if they give you the drum, sit on it and say, ‘Drum, drum, fly to the sun,’ and it will take you there directly. Only do not be afraid of anything you meet on the way.”

“Thank you,” said Anatole.

The trunk of the tree grew thick as a wall. Anatole could not even see where it curved around to the other side. He looked up into the branches. No light broke through at the top. The tree grew into a great darkness.

“It’s best not to think about the top,” said the North Wind. “It’s best just to start climbing.”

So Anatole put his foot on the first low branch and sprang up into the tree.

At first he found the climbing fun. He met nobody on the way except two squirrels who chattered to him, “What news?” Anatole smiled and shook his head. And then, as he had no one else to talk to, he talked to himself.

“It’s just like climbing the big pine tree in Grandma and Grandpa’s yard. When I was real little, it seemed like I’d never get to the top. Now I can shimmy up there easy, and I can look down and see Mr. Pederson across the street, mowing the lawn.”

Though he squinted, he could see nothing beyond the branches that surrounded him. They seemed to stretch out forever, and the discovery made him feel lonely and a little scared.

“Oh, but I’m not alone. Lots of things live in trees. All kinds of birds make nests in trees—”

He broke off. He did not like to think of all the things that might live in this one. He wanted, very badly, a peanut butter and jelly sandwich and a nice saggy sofa to lie down on, like the one at home. He sank so deeply into this thought that he nearly forgot to hold onto the branch. That frightened him; he stopped, trembling, and sat down to rest. And in the silence of his resting he heard a thin cold sound.

“Hsssss! Hsssss!”

Quickly he glanced up. No wind blew, but the leaves shook. Behind them white blossoms nodded to him. Blossoms or—he drew his hand back in alarm. What he had taken for blossoms was a tangle of snakes, smiling and darting their tongues at him. And now that he was afraid, they drew closer to him, whispering, “Hsssssss. Hssssss. Just you wait. Just you wait.”

He jumped up and climbed away from them, but the branches sprang back as fast as he pushed them aside. When he could not move forward or backward, he sat down again, wondering what to do. The branches locked him into the darkness. He listened for the snakes. He did not hear them, but something else waited behind the leaves and saw his fear and growled softly.

The wind rocked the branch he was sitting on, and he held it tightly, for he saw just behind the leaves, and very close to him, the faces of hideous dogs. Their eyes glowed like candles, and it seemed to Anatole that the whole tree was burning. Far off he heard the yelping of foxes and the cries of hunters.

With all his might, Anatole pushed himself through the thicket, closing his eyes so that he wouldn’t have to look at the dogs. And who knows where he might have ended up if he hadn’t bumped against a golden gate, set in a smooth golden wall that shone like a crown.

A goldfinch wearing a silver ruff opened the gate.

“Excuse me,” said Anatole hastily, for the goldfinch immediately tried to shut it again, “have you the drum that flies to the sun?”

“Are you the one that’s to have it?” asked the goldfinch.

“Yes,” said Anatole.

“Who sent you?”

“The North Wind.”

“Very well, I’ll fetch it,” said the goldfinch. “You may wait in my sentry box if you like. I’ve a bottle of dandelion wine on my desk. Help yourself. Have one for the road.”

Before he could do so, the goldfinch returned bearing the drum in its claws.

“Don’t jump off the drum till you reach the house of the sun. The moment you leave it, it will return to us.”

“I’ll be most careful,” said Anatole.

He climbed on the drum and said, “Drum, drum, fly to the sun.”

Immediately the drum swooped up and out of the tree, broke through the sky, and landed on a long white road in a broad, bare country. The road toward which the drum carried him ended at the door of a most peculiar house. It shone clear as glass and looked exactly like a pumpkin that has grown from a sunbeam. As the drum bumped along the road, an old woman appeared in the doorway.

“Well, well,” said the old woman, “what have we here?”

Anatole jumped off the drum and whoosh! it vanished.

“I’m looking for the sun,” said Anatole.

“Well, well,” said the old woman, “I happen to be his mother. What do you want with him?”

“I want him to give Erik Hanson his thirty lost years and to send me home again, for I don’t know the way and I can’t go home the way I came.”

“And what will you give me if I take you to see him?”

Anatole plunged his hands into his pockets. Nothing, nothing. No, wait, what was this? He pulled out the little advertisement for Van Houten’s cocoa.

“A little book, is it?” inquired the old woman. “What’s it called?”

“Van Houten’s Cocoa,” Anatole read bravely. “A Perfect Beverage combining Strength, Purity, and Solubility. Open here.” He wanted to weep.

“It’s magic, of course,” said the old woman. “Otherwise you wouldn’t have brought it. You would have brought me a cartload of pearls drawn by unicorns or a bushel of singing rubies. Such toys I see every day. But rarely does anyone bring me a magic book called Van Houten’s Cocoa. What does it do?”

Anatole shook his head.

“Come, come. Does it turn rain into tigers? Princes into cabbages?”

“No,” said Anatole.

And then he remembered the runes. So he put the little folder to his lips and over it he whispered:

“and the none was 1

and the 1 was 2

and the 2 was 3

and the 3 was 4

and the 4 was 5

and the 5 was 6

and the 6 was 7

and the 7 was 8

and the 8 was 9;

9 were Nothe’s sisters.”

“It’s all or nothing,” he added, and he opened the folder.

But instead of a tiny paper table set for two, there sprang forth a huge table set for forty. And such a setting! Wands of cowslip bread, platters of candied violets and marzipan marigolds, great tureens of daffodil soup and crocks of rose-petal jam. And in the middle, of course, stood a silver urn of cocoa from which flew a little pennant: Van Houten’s. On the table of the sun.

“Oh, that’s killing,” cried the old woman, “perfectly killing! It’s the best toy anyone has ever given me. Let me try it.”

She shut the folder and the banquet disappeared.

She opened it and the banquet returned. The bread was still warm. Anatole had never smelled anything so delicious.

“Well, well,” said the old woman, seizing a loaf and biting into it, “help yourself.”

“Thank you,” said Anatole. He ate two loaves of bread and three plates of violets, and then he laughed. What if his mother, who was always saying, “Eat, eat,” could see him now! He felt so much better that he began to believe things would go well for him after all.

“What about the sun?” he inquired.

“Ah,” said the old woman, “he’s shining over Asia. Would you like to watch him?”

She led Anatole into the round glass house. In the middle gleamed a pool of water, and in that still water he saw the sun, but how different the sun looked in this mirror than in the skies at home. No moving ball of fire but an old man the color of embers, wearing a raven on each shoulder, and with each step he took, he grew older still.

“He’ll be half dead when he arrives,” said the old woman, “and that is the time to catch him, for that’s when he’s the wisest. You must meet him on the road, for when he passes through the doorway of this house, he will turn into a little child, and then there’s no seriousness in him at all, and he won’t help you a bit.”

So Anatole, sipping his cocoa, watched for the old man on the road. But the old woman saw farther than Anatole.

“That’s he,” she said. “Run to him quickly before he reaches the door.”

Anatole bounded out of the house and down the road till he met the sun, who was creeping along, white-haired, squint-eyed, and more wrinkled than the sea. “Grack! Grack!” clucked the ravens on his shoulders.

“Sun!” called Anatole.

The sun peered all around him.

“Where are you?” he croaked. “I don’t see well now, and my hearing is bad.”

“I’ve come to ask you about Erik Hanson.”

“Erik Hanson of Sellebak?” said the sun. “What about him?”

“He’s lost thirty years of his life, and he wants them back.”

“Well, he can’t have them,” said the sun crossly. “I won’t give him time, but I will give him knowledge. He shall know everything that happened to him during those years. Will that do?”

“I guess it will have to do,” said Anatole.

“I will send him my servants, Thought and Memory, my two trusty ravens who tell me all that goes on in the great world. They will show him his past. They’ll show him how to turn hurts into blessings and dragons into princesses. And if he listens to them, he will be the greatest storyteller in Norway.”

“He’s a good storyteller right now,” said Anatole, remembering how Erik once described his mother as a kangaroo.

“But if he does not want this knowledge,” continued the sun, “he should send my servants away. Sometimes people forget what it causes them pain to remember. It is not easy for a soldier to remember the faces of the people he has killed.”

They had arrived at the door, and no sooner had the sun passed through it than zzzzzz! the old man vanished and there stood a child, scarcely a year old, babbling and laughing and tumbling on the floor.

The old woman dipped the corner of her apron in the pool and scrubbed the child’s face, and snatching a loaf of bread from the table, she pushed it into his hand.

“And now, outside with you. You must go and wake the children in Brazil.”

“Wait!” cried Anatole. “You must tell me how to get home again.”

But the sun ran laughing out the door.

“That’s a pity,” said the old woman, shaking her head. “Now you’ll have to wander the earth until you find your road, for the sun talks to a man only once in his life, and you’ve had your chance.”

“THE OLD WOMAN DIPPED THE CORNER OF HER APRON IN THE POOL AND SCRUBBED THE CHILD’S FACE.”

Anatole burst into tears. But suddenly he felt a flutter of wings brush his cheek, and there on his shoulder sat the sun’s raven.

“I am Thought,” cawed the raven, “and I offer you my services. You cannot return home the way you came, by drum, by tree, or by wind, for the connections are uncertain and none of them runs on time. But I am swifter than the drum and the wind, and I am not rooted in any one place like the tree.”

“What must I do?” asked Anatole.

“Think of your home. A real magician isn’t afraid of what he doesn’t understand. You are a real magician now.”

So Anatole thought of his house and his swing and his mother singing “Awake, Ye Wintry Earth,” and how she would soon go to the kitchen and start supper, meat loaf, maybe, and he thought how his papa would come home with a newspaper for himself and a gingerbread man for Anatole from the bakery, and he thought how no place was nicer than this place where two people loved him.

And he found himself sitting on his swing at twilight.

•

But this is not the end of the story. Two days before Christmas, early in the morning, Anatole saw a large black bird drop something on the windowsill outside his room. He opened the window and found a reindeer’s tooth, which he recognized, and a book, which he did not. On the cover he read Erik Hanson’s Saga. And inscribed on the flyleaf was the following message: