They came to rest on an island in the middle of a lake, close by a small house, which was cobbled with seashells from top to bottom. The shutters were thrown open, and there was an awful row going on inside. Before Anatole could find the door in its side, the fish flew straight up to the roof and dived down the chimney and landed softly in the middle of an enormous room.

A piano whistled past them. Books circled the room like lost birds. Gravestones, steeples, lanterns, armchairs, and fishnets flew over the heads of four men whose white hair streamed around them as they stood in the four corners of the room and shouted. You could tell who was the North Wind, for he was the biggest and strongest; and you could tell the East Wind, for he was the youngest and smallest; and you could tell the South Wind, who was very handsome and looked as if fighting really did not agree with him at all. That left only one more, a rather mysterious figure dressed entirely in black, who Anatole concluded was certainly the West Wind—since the others had been accounted for.

“The cupboard belongs to me! I found it!” shrieked the East Wind.

“Then give me back my suitcase,” the West Wind hissed.

A suitcase sailed across the room. The West Wind snatched it out of the air and inspected it.

“You’ve torn the hinges!”

“You tore them yourself!”

Suddenly the four winds caught sight of the fish.

“Brothers,” shouted the South Wind, “our sister has sent us a present.”

They all wanted to have it, of course, and they began tumbling the fish to and fro about the room. Hearing shrieks from inside, they turned it upside down and shook it till the passengers came rattling out like peas in a shooter, and then the four winds grew still with astonishment. In all their travels they had never seen a company exactly like this one. The East Wind pulled Captain Lark’s ears, the South Wind picked up Anatole and Quicksilver and juggled with them, the West Wind balanced Plumpet on his thumb, and the North Wind set Susannah gently on his palm and brought her close to his great eyes, for he was very shortsighted.

“This creature’s made of living glass,” said the North Wind, raising Susannah like a goblet, “so we mustn’t throw her about. Be careful with the others as well, brothers. They, too, may be alive.”

At once the South Wind set Anatole and Quicksilver on the floor, and the East Wind stood Captain Lark beside Anatole, and the West Wind arranged Plumpet between them, as if he were setting up pieces for a game of chess.

“You should have told us you were alive,” scolded the North Wind, and he shook his finger at Susannah, who was huddled in the palm of his hand. “Those who ride our breath seldom arrive with any of their own. I can see that our sister sent you. Why?”

Anatole, still reeling, stepped forward, and the four brothers turned their ears toward him, so that they would not miss a word. Then he explained why he had left home and how he had met Susannah and Captain Lark and how they escaped from the dogs and how he meant to find the key and free the King of the Grass, unless Mother Weather-sky found it first, only he didn’t know where to look for it. When he had finished, the North Wind spoke.

“You’re a plucky fellow, and I like plucky fellows. I know where the key is. Maybe you’re the lad that’s to have had it?”

Anatole did not know what to say to this, but the North Wind did not wait for an answer.

“Not even my brothers know where the key is. And all sorts of folks come to me asking for it. They’ve heard of a golden castle, you know, and they want to get rich. Do you want to get rich?”

“I want my grandmother to get well.”

“Well, you’re the right one,” said the North Wind. “The golden castle was nothing but one of the Magician’s illusions. However, I never give anything away, not even to heroes. It’s bad for business. What have you got to trade?”

“What do you want?” asked Anatole.

“Look around. What do I need?”

Anatole looked around. So did Plumpet and Captain Lark and Susannah, and even Quicksilver turned slowly around, so that the wealth of the winds was reflected in his bright side. It seemed to Anatole that the winds needed nothing, except perhaps a housekeeper to tidy their belongings.

“You have everything,” said Susannah.

“Never mind that. What can you offer me?” asked the North Wind.

Susannah’s whistle began to glow, and Anatole hastily stepped in front of her, for fear the North Wind would ask for it. Then he put his hand into his left pocket, hoping to find his harmonica, but to his great disappointment he found nothing but a yellow card.

The North Wind drew forward eagerly.

“What’s that?”

“That’s my YMCA card.”

“What does the writing on it say?” demanded the North Wind.

“It says I belong to the YMCA.”

“And what is the YMCA?”

“It’s the place where I go swimming with my friends on Saturday mornings.”

“And of what use is this card?”

“I show it to the lady at the door and she lets me in.”

“Glory and onions!” shouted the North Wind. “All my life I’ve wanted people to let me in. They lock their doors. They button up. They won’t listen. Did you say she’ll have to let me in?”

Anatole read the card once more. It said nothing about not admitting the wind.

“If you show this card, she’ll let you in.”

“It’s a trade!” The North Wind blew the card into the air, caught it between his teeth, rolled it up, and tucked it into his ear, which looked as if it were smoking.

“And now I’ll tell you all I know about the key. It’s hidden in Mother Weather-sky’s garden, and I can take you there. But you must wait till I load my pack and put on my skis.”

The South Wind and the East Wind were riding the fish around the room, while the West Wind ran after them, clamoring for his turn and shouting that the fish was growing fainter and fainter and would soon disappear. But the North Wind fetched a large leather bag from a hook on the wall and strode around stuffing various articles into it, including the West Wind’s suitcase. He never liked to keep things long anyway; it was the getting and the getting rid of them that pleased him most. Next the North Wind put on his cape and took down his skis from their rack over the door and strapped them on his feet.

“Time to go,” he said. “Jump on my pack.”

“We’ll be blown away,” protested Susannah.

“Hold fast to my hair, then,” said the North Wind. “I shall not feel it.”

First Anatole climbed up, holding Quicksilver. Then Susannah got behind him with Plumpet in her arms. And last of all was Captain Lark, because he was the tallest and his arms reached around everyone else and kept them in place like the sides of a ship. The North Wind opened the door, took a deep breath, and pushed off.

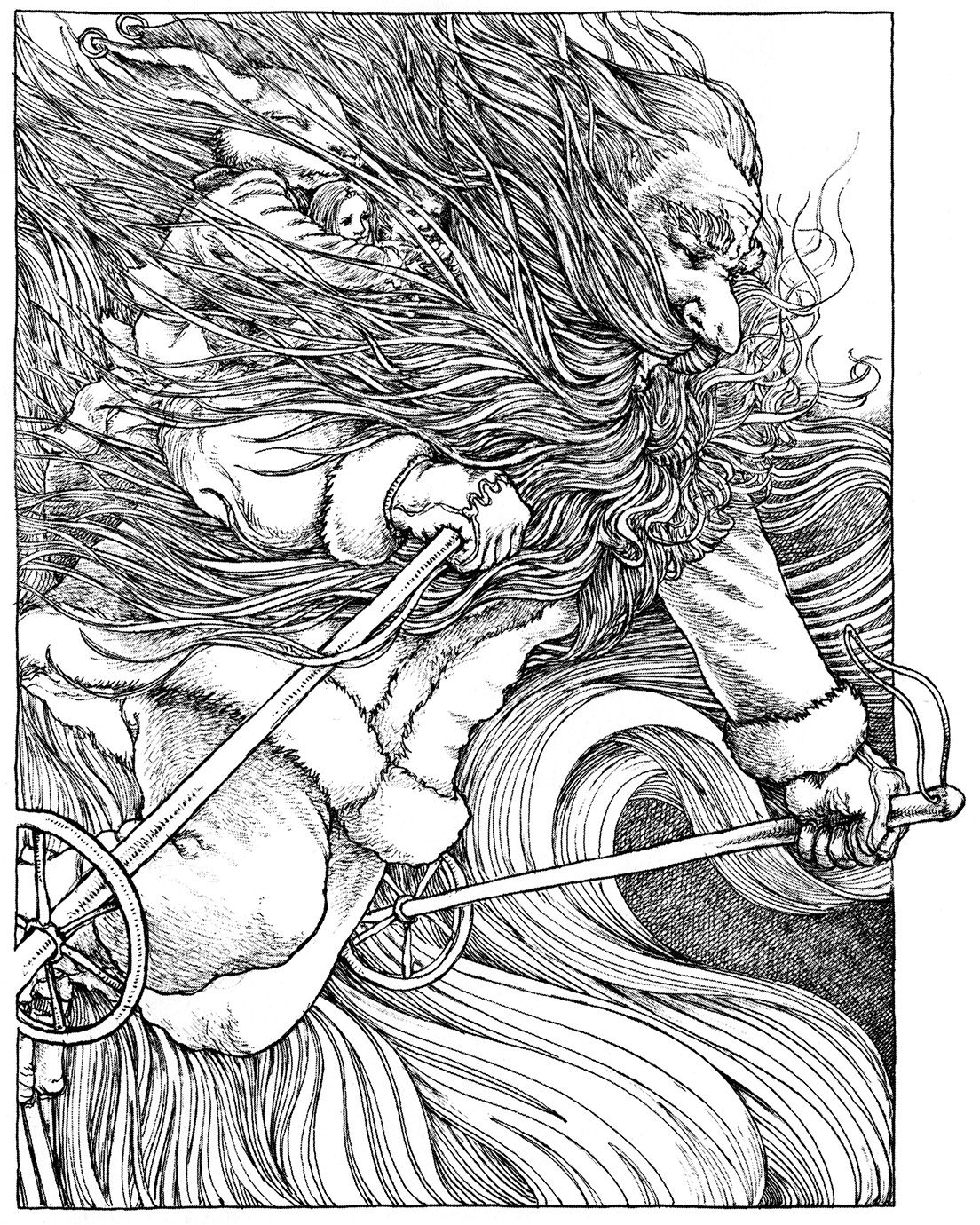

What a fine figure he made, skiing down currents of air and shouting to himself.

“Look down,” he called over his shoulder. “Once upon a time those trees were towers and cloud-capped palaces. On still days, when I’m not around, you can hear bells ringing in the ground.”

“Bells ringing in the ground?” repeated Anatole.

“The Magician couldn’t change them, so he buried them. Below us is Mother Weather-sky’s garden. Jump off now.”

But his passengers clung to his hair like burrs.

“WHAT A FINE FIGURE HE MADE, SKIING DOWN CURRENTS OF AIR AND SHOUTING TO HIMSELF.”

“Jump off! Or I’ll shake you off.”

And since they would not let go, the North Wind arched his back and sent them flying into a holly bush. They had hardly landed when lightning exploded all around them, bushes were ripped from the earth and hurled into the sky, branches rushed through the air like bits of paper, and a huge tree lurched in front of them and fell, screeching like an animal. The storm did not touch the holly bush where they lay, but the forest around them was being laid waste. A thunderous baying of dogs made Anatole glance up in terror. Through the leaves of the holly bush, he saw a pack of dogs running through the air overhead, and he recognized them as those dogs that had taken them prisoners. On the back of the Great Dane rode an old woman in a green cloak, and she was braiding whips of lightning and tossing them into the trees. The dogs sank lower and lower and raced yapping around the holly bush.

And then, just as suddenly, the air was so still that Anatole could hear the pounding of his heart. Cautiously, he peeped out and what he saw in that deep silence astonished him. The broken trees were mending themselves, standing up and putting forth new leaves and new boughs. Moss and partridge berries and wild mint were covering the forest floor once again.

“Who saved us?” whispered Susannah.

In the silence that followed, a small voice said, “I did. Though I am smaller than Mother Weather-sky, my spells are stronger.”

“Who are you? Where are you?” cried Anatole, glancing around but seeing nobody.

“Look down,” murmured the voice. “I’m resting on your shoe. Just a moment, I’m changing. Now you’ll see me.”

Across his left sneaker a tenuous shape appeared, a small green flame that grew brighter and brighter but gave off neither heat nor smoke. Anatole stooped and put out his hand, and a chameleon glided over his wrist and arranged itself on his palm.

“It’s always hard for me to make myself different from what keeps me. Can you see me now?”

“Oh, yes!” everyone exclaimed. They could not take their eyes off the tiny lizard. It had silver claws and iridescent skin, and when Anatole lifted it for the others to examine, it turned its head this way and that and blinked its ruby eyes at them and darted its tiny blue tongue, fiery and forked, like a bolt of lightning.

“How lovely you are,” exclaimed Susannah. “But how do you know Mother Weather-sky?”

“I can’t tell you that,” answered the chameleon. “I can only show you the road to her house.”

“If your spells are stronger than hers, won’t you make us good and wise and strong?” pleaded Anatole. He was certain the chameleon could make them invincible if it wanted to.

“What gifts can I give you that you haven’t already got?” asked the chameleon softly. “Haven’t you escaped the dogs and traveled on the wind? Haven’t you survived Mother Weather-sky’s storms and darknesses?”

This was true. But just then it did not seem enough.

“To reach Mother Weather-sky’s house,” continued the chameleon, “you must stop at her sister’s.”

“We’ve already met her sister,” said Plumpet.

“You met her older sister. You haven’t met her younger sister. The door to her house lies in the stream. You must go back the way you came.”

Anatole set the chameleon down. Feeling solid ground under its feet, it slipped away into the darkness, but its skin gave off a trail of sparks, which flared up for an instant—long enough to light the path—and then died away and flared up again farther on. The travelers followed till the earth grew soft underfoot and the rushing and tumbling of water sounded close by.

“Stop,” cautioned the chameleon. “I don’t want you to fall into the stream.”

“What must we do now?” asked Plumpet, who disliked getting wet paws under any circumstances; she always caught cold afterward.

“You must wait for the full moon,” answered the chameleon.

“Heavens,” exclaimed Captain Lark, “we may be stranded here for a month.”

Nevertheless, he sat down between Anatole and Susannah on the banks of the stream. Susannah was nearly invisible, like a window in a dark house, and Quicksilver was all darkness, but the others could hear him stamping happily in the mud. Plumpet alone waited with grace and goodwill. Years of waiting at mouseholes had given her great patience.

Suddenly Susannah glowed with a lacy radiance; her glass body held the silvery branches of trees. Anatole scanned the sky for a full moon.

“You’re looking in the wrong place,” said the chameleon. “Go down.”

They looked down. The full moon shone clear and pale in the water.

“I see a door,” said Susannah.

“That’s not a door,” Anatole corrected her. “That’s the moon’s reflection.” But the moment he said it, he was not so sure. Behind the gauzy circle on the water he saw a long stairway that led down into the stream, and he was quick to point it out to the others.

“I suppose I must take the plunge,” said Plumpet with a sigh.

“I can’t swim a stroke,” said Captain Lark.

“That’s odd for a pirate,” observed Anatole.

“It is, isn’t it? But it’s so.”

“I’m afraid I shall simply sink,” said Susannah.

“Can none of us swim?” asked Captain Lark. “We need someone who can save us. Anatole, can you save us?”

“I can swim,” said Anatole, “but I can’t save anyone. I’m still in the beginner’s class.”

“You can swim,” said the cat. “I vote Anatole go first.”

“And I’ll go next,” volunteered Susannah, “and I shall hold your paw, Captain Lark, if you’d like me to.”

The cat, the rabbit, the glass girl, and the coffeepot lined up on the bank. Anatole took a deep breath and held his nose and jumped—he had not yet learned how to dive—into the white circle.