The city is full of magic,” said Uncle Terrible, “but rest assured, Anatole, that women do not turn into birds. Perhaps it flew in from the kitchen.” He paused on the dark landing and puffed a little. “That was stair number eighty-eight. We have eleven more to go.”

Anatole leaned over the banister. It wound down, down, like a far-off road, all the way back to the first floor. A milky light sifted through the skylight overhead, where someone had hung a dozen spider plants that trailed their branches toward them.

At the top of the last landing were two doors.

“Mine’s the left one,” said Uncle Terrible.

He took a large key from one of his pockets and fitted it into the lock.

“Why do you have two keyholes, one so high up?”

“You mean the peephole? That shows me who’s on the other side of the door before I open it,” replied Uncle Terrible. “Open sesame!”

And with a turn of the key, the door sprang open.

“Behold,” said Uncle Terrible.

In the middle of the room, rising out of a sea of newspapers, old grocery bags, and dirty laundry, stood a doll’s house. It was taller than Anatole; it was nearly as tall as Uncle Terrible himself. Built of rosy brick, it had a widow’s walk on the roof and a front door, dark blue, with a round brass knocker that glimmered like a friendly moon, and French doors tall enough to walk through—if you were small enough.

“Oh, Uncle Terrible!”

“A gift from an unknown admirer,” said Uncle Terrible. “I found it on the fire escape. I asked around the building if anyone had lost a house, but no one claimed it. Welcome to my quiet retreat from—” and he waved his arms at the disorder of the apartment, as if he were commanding it to disappear.

“Let me show you around,” he said, and he took a very small key from a very small pocket in his vest and unlocked the front door of the little house. The door did not open. But the entire front of the house swung open, like the door of a cupboard.

Anatole could scarcely believe his eyes. Three master bedrooms, each with a canopy bed, and a living room with a ruby glass chandelier and a sofa upholstered in red silk, and a large kitchen painted in red, white, and blue, and a bathroom—why, the bathtub was gold! It crouched on four feet that ended in silver claws.

The most remarkable room was the library, just off the kitchen. At the table in the center, a dozen mice could have dined in comfort and afterward stretched out on the purple plush carpet for a nap, or curled up in one of the two armchairs, upholstered in leather. To Anatole’s delight, the bookshelves were crammed with books, yet the largest volume was no bigger than a postage stamp. The boy took down a green one and opened it. The cover was soft and brilliant as moss, and the lines of the text lay close together, like strands of hair.

“Uncle Terrible, have you a magnifying glass?”

“I have no magnifying glass strong enough for that book. Put it back.”

He sounded so disturbed that Anatole felt he should never have asked. For the first time that day, he wanted to go home. Uncle Terrible broke the silence between them.

“If you want to wash up for dinner—” He touched a faucet in the bathroom, and a pearly thread of water flowed into the silver sink. “Hot and cold,” he announced proudly. “The stove in the kitchen works too. You can cook a small dinner for one large person, or a large dinner for six small persons. And in the evening—” He pressed a button in the living room, and the whole house lit up from top to bottom. The ruby chandelier glittered, throwing tiny rainbows on the ceiling like confetti.

“I used to have two chandeliers,” Uncle Terrible observed. “The other was made of emerald glass. One night the emerald chandelier simply vanished. Make yourself at home, Anatole. I have to straighten up the outside world.”

And he bustled about the big room, stuffing clothes into drawers, pushing boxes into closets, and as if by magic there came into view a four-foot inflatable King Kong by the front door and a Frankenstein mask on the wall and a comfortable jumble of overstuffed chairs and a floor lamp with an awful tasseled shade and an African violet on a pedestal and a red plush sofa that reminded Anatole of a kindly old man with a sagging belly.

Just in front of the little house, something gleamed through a knot in the floorboards. Anatole put his eye to it. To his disappointment, another eye did not meet his.

“Uncle Terrible, you have a blue marble under your floor. Let’s rescue it.”

Uncle Terrible shook his head. “We’d have to pry up the boards, and that would disturb the cockroaches. I sweep all my cookie crumbs into that crack, and the cockroaches never bother me. We’ve had the arrangement for years.”

“May I call them cockroaches too, Uncle Terrible?”

“Why, what else would you call them?”

“Mom calls them Martian mosquitoes. If you say, ‘I just saw a Martian mosquito in the kitchen,’ nobody will know you have cockroaches.”

“But why shouldn’t people know? Everybody in the city has cockroaches. The people who think they don’t have them have the polite kind that mind their own business. Let me show you your bedroom. It connects to the bathroom. You won’t mind my tiptoeing past you during the night? Give me your knapsack.”

Beside the brass bed in the back room was a roll-top desk. Wham! Uncle Terrible, who was a high school Latin teacher, pulled the top down on a Latin dictionary and a clutter of papers, and now the room was perfectly tidy.

“A lovely view of the fire escape,” said Uncle Terrible, pointing to the window. “And if you want a night light, you can borrow my Statue of Liberty.”

There she stood, on top of the desk, gazing out the window.

“Can I pick her up?”

“Of course. Can you read the fine print on the base?”

Anatole read it easily: “Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free.”

“You know, the first penny I ever earned came from my Polish grandmother,” said Uncle Terrible, “and she gave it to me for learning the rest of that poem by heart.”

“Poem?” said Anatole, puzzled.

Uncle Terrible gravely recited it:

“Not like the brazen giant of Greek fame,

With conquering limbs astride from land to land;

Here at our sea-washed, sunset gates shall stand

A mighty woman with a torch, whose flame

Is the imprisoned lightning, and her name

Mother of Exiles. From her beacon-hand

Glows world-wide welcome; her mild eyes command

The air-bridged harbor that twin cities frame.

‘Keep, ancient lands, your storied pomp!’ cries she

With silent lips. ‘Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me.

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!’”

“Very nice,” said Anatole, though he was not sure he understood it.

“Now I want you to listen carefully, Anatole,” said Uncle Terrible. “We’re clean out of milk, and I’m going to the store at the end of the block. I won’t be gone more than twenty minutes. Don’t open the door to anyone but me.”

“I promise,” agreed Anatole. “Can I play with the little house?”

“Yes. But don’t turn anything on. And don’t touch the books. Here. Have a stick of bubble gum.”

“My mom said—”

“It’s sugarless,” said Uncle Terrible.

“Thanks,” said Anatole, and he popped the gum in his mouth.

As he knelt by the little house, he could hear Uncle Terrible humming his favorite tune, “Blue Moon.” His footsteps grew fainter and fainter. Anatole opened the door of the oven and discovered a pile of dirty dishes. The plates were the size of buttons, the coffee pot no taller than a thimble. To Anatole’s surprise, the oven was warm.

But he had promised he wouldn’t turn on the oven, or the stove, or the lights, or the water.

But he could explore the apartment. Where would Uncle Terrible sleep? On the sofa, probably. He had given Anatole his own bed.

Anatole opened the door nearest the sofa. Uncle Terrible’s jackets hung in a row, like a parade of ghosts. The smell of cigars still clung to them. How funny to have so many jackets! Anatole had only his windbreaker with the souvenir patches. None of Uncle Terrible’s jackets had souvenir patches.

He opened a high thin door in the kitchen, and a little ironing board dropped out as far as its hinge would allow and struck him on the shoulder.

He opened the door beside the awful tasseled lamp, and a bed sprang out. It too was fixed at one end of the wall. So this was where Uncle Terrible slept. Anatole pushed the bed up, and to his relief it folded itself away obligingly, and he shut the door on it.

He opened a fourth door beside the pot-bellied sofa. Ah, this was where Uncle Terrible kept his comics! Four columns of comics that reached all the way to Anatole’s waist. He sat down on the floor and plucked one from the top of the neatest column. What if Doctor Strange had served Dormammu instead of the Ancient One?

Mint condition. He turned to the first story.

Thump, thump.

What if Uncle Terrible came back and found him messing up his comics?

Thump.

But that wasn’t a footstep on the stairs. The noise came from the opposite direction.

Thump.

From his room.

Thump, thump.

He shoved the comics into the closet, jumped up, and was just closing the door when a high voice outside the window sang,

“My father is a butcher,

My mother cuts the meat,

And I’m a little wienie

That runs around the street.

How many times

Did I run around the street?

One, two, three—”

Anatole ran into his bedroom, unlocked the window, pushed it open, and crawled out on the fire escape. Drops of rain hung glistening from the railing. A tiger cat stared at him with sad eyes as if to warn him, “Go back, go back, home is best,” before it scampered away.

At the top of the fire escape, a girl in her nightgown was skipping rope. When she caught sight of Anatole, she called down, “I heard you talking. Are you sick, too?”

“No,” Anatole called back.

“Why aren’t you in school?”

“We’re on holiday. What’s wrong with you?”

“I have the flu!” shouted the girl. “And I’m so bored. When Grandma comes back from the store, I’ll have to go back to bed.”

Skip, skip.

“My name is Rosemarie, and my grandma has a garden on the roof. Come on up. I’m mostly well.”

Anatole paused, halfway up the stairs.

“Uncle Terrible told me not to let any strangers in the house.”

“Grandma told me the same thing,” said the girl. “We’ll play outside.”

She darted back up to the roof, her black braids blowing behind her.

The fire escape shook so violently that Anatole did not dare look down, for he could see through the steps into the alley nine flights below.

“The roof,” said the girl, “is the best place of all.”

There were tubs of geraniums and pots of chives. Both grew as thick as in his mother’s garden at home, and just such a pebbly path led through her garden as snaked among the pots and tubs in this one.

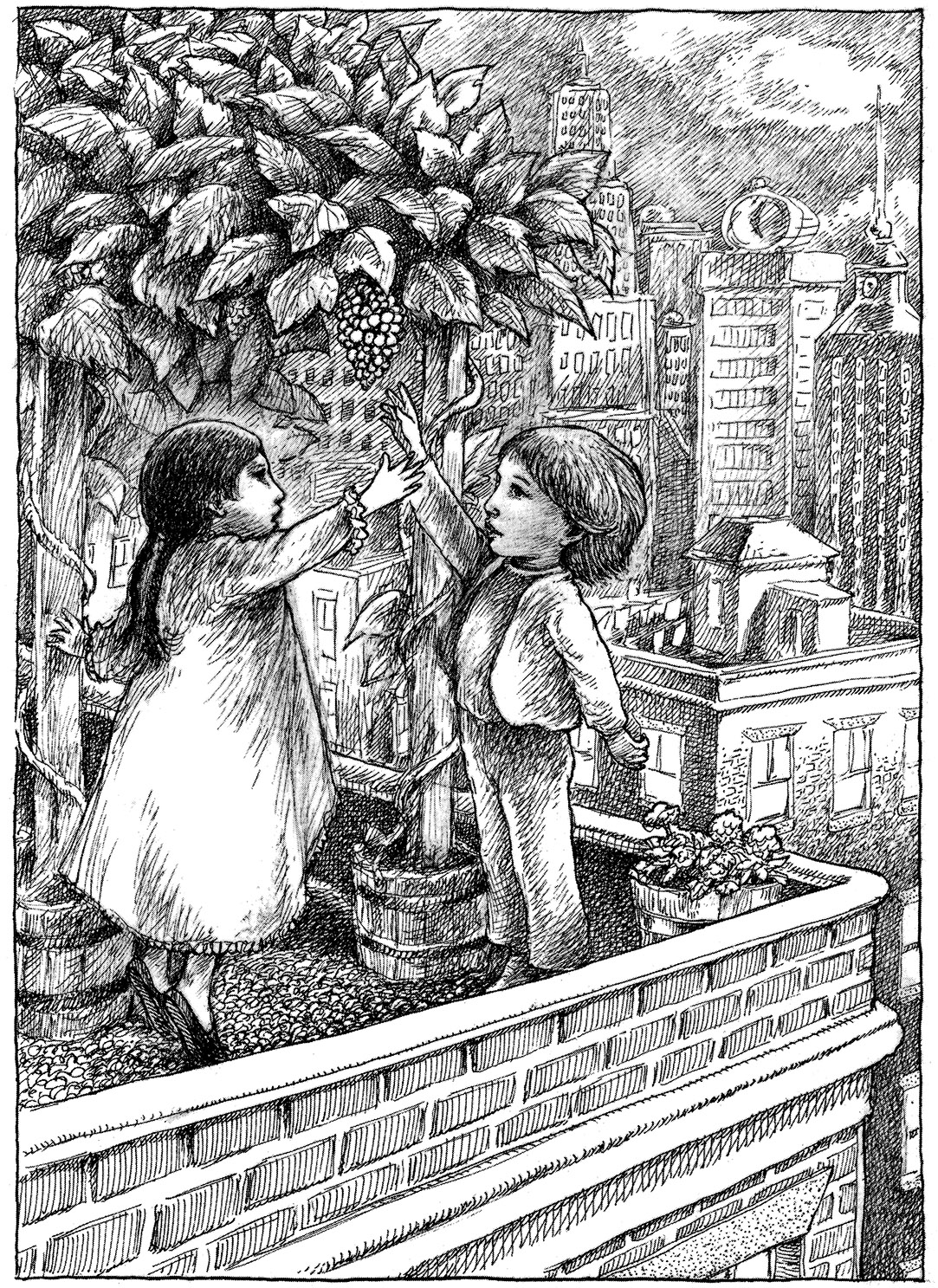

But his mother did not have a stone table and two wooden benches and half a great blue tub turned on its end with the Virgin Mary inside holding out her hands, and his mother didn’t have a grape arbor, thickly woven with stems and bunches of grapes, both green and purple, hanging inside. Anatole reached for a grape, but the girl grabbed his arm.

“They’re not real,” she said. “But our doves are real. Come and see our doves.”

The doves lived in a snug little tower like a pagoda. It had hundreds of windows through which the doves could come and go, though none were to be seen just then. But Anatole could hear them, cooing inside, and when the girl opened the door, there sat the doves on their nests, some white, some brown, and each family in its own room. The birds blinked at the children and clucked and scolded, and the girl closed the door again.

“I saw an owl in a coffee shop today,” said Anatole. “And I met a magician. He gave me a fan with dragons on it.”

He was tempted to add that he had seen a woman turn into that owl before his very eyes, but Uncle Terrible had said women never turned into birds. She had disappeared though. Very likely into the ladies’ room.

“An owl? Was it tame?”

“No, it flew outside.”

“ANATOLE REACHED FOR A GRAPE, BUT THE GIRL GRABBED HIS ARM.”

“Maybe we’ll see it,” said the girl.

From the garden they could look out over other rooftops into a forest of television antennas and ventilation shafts. They could look right into other people’s windows. They could look down at the cars, small enough to fit in their hands. Then they could look beyond the buildings to the river and the train tracks and the turrets of Himmel Hill.

Close by, bells began to chime. The girl pointed across the street to a church and a schoolyard next door. Children were running in from recess.

“That’s my school,” said the girl. “I hate it. We aren’t allowed to talk during lunch, and we have to say catechism every morning with Sister Helen.”

Suddenly Anatole caught sight of a familiar figure in a tweed jacket and a red shirt and rainbow suspenders crossing the street toward them.

“I have to go home,” he said, “right now.”

As he ran down the steps, the girl called after him, “I’ve always wanted a fan with dragons on it.”

“I’ll leave it for you on the fire escape,” Anatole called over his shoulder.

After a frantic search, he spied the fan behind the little house. He stuck it to the fire escape with his bubble gum and was fumbling with the lock on the window when he heard someone fumbling with the lock on the door and Uncle Terrible strode into the apartment, his arms full of groceries. Anatole hurried to meet him.

“I’ve been thinking,” exclaimed Uncle Terrible, “that it’s a great afternoon to visit the Guinness Book of World Records Museum. And we can take dinner at a little place I know that serves the best spaghetti in town.”

•

After dinner Anatole was tired but also content, for it isn’t every day you can try on the belt of the fattest man and afterward eat all the spaghetti you want for supper. Though at home he never went to bed before nine, he did not object when at seven o’clock Uncle Terrible announced bedtime for both of them and unfolded his own bed in the living room. He graciously accepted Anatole’s gift of comics and promised to let Anatole pick six from his own collection, in fair trade. He had left a book on mummies by Anatole’s bed and a silver bell and a glass of milk and a box of Fig Newtons, and he told the boy he could turn on the Statue of Liberty and sleep in his clothes, including his baseball cap, and he could read as late as he liked.

But he must stay in his room. On no account should he open his door after eight o’clock.

In an emergency he might ring the bell.

Yes, that was fine with Anatole. He pulled on his jacket and climbed into bed, examined all the photographs of mummies in the book, thought how much he would like to have one, and turned off the overhead light. He thought how delightful Latin would be if he had Uncle Terrible for a teacher. The Statue of Liberty glowed, as if a star had fallen into the room.

If he were home, his father would sing to him before he turned off the light.

“Get on board, little children,” Anatole sang to himself, since there was no one to sing it for him.

He dozed off at last.

He had scarcely fallen asleep when a clap of thunder woke him—bang! bang! The rain roared down, the window blew open, the door flew open, and Anatole jumped out of bed to close it.

What was that faint light in the living room? Was Uncle Terrible awake? Was he ill? No, not ill.

He crept into the living room. The light came from the little house.