CHAPTER 2

Staying Active

with Elizabeth Conner

Flexing one’s bicep has become a symbol of manliness in many cultures. In societies that equate being a man with strength and independence, the decline of muscle mass that accompanies physiological aging can be one of the most challenging aspects of growing older. Men are expected to be able to tote heavy objects. We are expected to be the physical and metaphorical “protector” of the household. But the fact is that our muscle mass begins to decline at a rate of about 1 percent per year starting around age 45. The gradual loss is intrinsic aging and called sarcopenia;1 it is also determined by lack of exercise and protein deficiency. Fortunately, there are precautionary measures one can take to prevent, or significantly delay and barely notice, the natural erosion of muscle mass. Participating in regular exercise is crucial. Someone once said, “Regular physical activity is the closest thing there is to a miracle drug.”

The relationship between physical activity (and exercise) and healthy aging is both complex and simple. The “complex” is the many ways that physical activity determines healthy aging, and this is examined in greater detail in the rest of the chapter. The “simple” is that along with eating well, physical activity in whatever form, whether a daily exercise routine or 60 minutes of walking while at work, is the line of defense that keeps us healthy and independent.2

Compared to men who are sedentary, being physically active greatly helps maintain our health and functional ability. The evidence is so strong that researchers and clinicians now advocate that all men—even sedentary 75-year-olds—engage in moderate physical activity (defined below) on a regular basis.3 Because physical activity alters the pace at which our bodies age, you are never too old to gain a positive result from exercise. Simply by standing, you burn three times as many calories as you do sitting. Walking your dog in a grass field burns three times the calories as walking on a paved street. Studies have shown that regular exercise by middle-aged men can set back the clock 20 to 40 years when compared to men who are inactive.

Three reminders are important. First, many men want an instant fix to their now sedentary lifestyle and the weight gain that took years to accumulate. Add a pound a year from age 35 to 50, and odds are that you barely noticed the weight gain. You might not have even changed pant size and do not feel it necessary to carve out a half hour or more several times a week to “work out.” You can also forget the empty promises of the paid programming on television that sell you a sculpted body in 60 days with their exercise equipment and special diets. While it might well be possible for three or four out of 100 men, odds are you won’t be able to integrate their fitness plan of intensely working out every day for months and months and months. The real goal is to construct a healthy lifestyle of your own—one that includes physical activity, perhaps even an exercise routine, but one that fits your needs.

It’s difficult to fully appreciate that maintaining moderate physical activity is for the long haul; it will make a noticeable difference 10 years from now, not next month. The objective is to change our lifestyle choices—engaging in regular physical activity versus continuing to be inactive. All adult men need to schedule active time and quiet time for ourselves within our daily routines and stick with the ways we find comfortable to stay active. We also need to manage the demands of physical activity on our bodies. Energy conservation is the way activities can be done to minimize fatigue, joint stress, and pain—such as a slow steady rate of work with frequent short rest breaks, planning your heavy activities to fit your own best times, and analyzing the work to be done in order to eliminate unnecessary steps. When we use our bodies efficiently, we can remain physically active well into our eighties and nineties.

Second, there is an aging myth that needs to be met head-on. Many people think that getting older is associated with a decline in physical activity. Is it? Reverse the cause and effect. Have you ever considered that inactivity may actually be a cause of much of our (early) physical aging? Inactivity in fact accelerates age-related changes in our muscles, joints, and endurance.

Third, there is no doubt that the age-related changes in our metabolism affect our bodies, and the decline in testosterone can make staying physically active more challenging as we get older.4 However, staying active (and eating well) is the fountain of healthy aging—it slows the pace of intrinsic aging.5

Being physically active improves metabolism and reduces appetite, puts a brake on the falling off of testosterone, and fights off the natural erosion of muscles, bone density, and flexibility. Being active maintains cardiorespiratory fitness and heart health. It lowers the risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease6 and other serious health challenges, including later-life diabetes. Staying physically active keeps our mental functions sharper and promotes brain health. It also supports mental health—we feel better about ourselves, even when facing troubles.

PHYSICAL ACTIVITY VERSUS EXERCISE

For many of us, the prospect of running a 5K or playing in an over-50 basketball league sounds more like punishment than fun. Even thinking about exercise sometimes seems like an unpleasant chore because we simply find it difficult to fit it in when already working long hours. Whatever the case may be, there is an important distinction between being physically active and exercising. To clarify, exercise always involves physical activity, but physical activity does not have to be exercise, and it can still provide many of the same benefits.

When you think of exercise, picture what you did during a high school gym class or sports practice—jumping jacks, running (long distance or sprinting), or some kind of weight training. While the benefits of these activities are undeniable, they require a certain time commitment and physical capability. If you have the time, physicality, and, of course, willpower, by all means exercise on a regular basis—take a run or get on a bike. If you lack the stamina or strength but have the desire, start out slowly—take a walk and begin to own the feelings of being active.

Physical activity is less regimented than an exercise routine and can often be done without totally interrupting daily life. Physical activity is simply using your muscles and putting your body in motion. Examples include mowing the lawn (as long as it isn’t a riding mower), taking the stairs rather than the elevator, washing your car, going for a walk in a park, and throwing the football with your grandson. In these examples, you are either doing chores, getting where you need to go, or enjoying your family while engaging in some cardiovascular activity. As with exercise, some types of physical activity are more beneficial than others. Taking out the trash does not give you a free pass for extra dessert. There are, however, alternatives that, when done regularly, can help keep you in shape and protect against ailments, such as high blood pressure and diabetes.

BENEFITS OF PHYSICAL ACTIVITY

Domain |

Benefit |

Comments |

Health and fitness |

↑ Moderate to large |

Improves general health, and reduces risk of illness (e.g., cardiovascular disease) |

Brain health |

↑ Small to moderate |

Improves your mental sharpness and insight |

Mental health |

↑ Small to moderate |

Improves your spirits and gives you more positive outlook on life |

Energy level |

↑ Moderate to large |

Increases your energy level and vitality |

Functional capacity |

↑ Moderate to large |

Keeps you independent and improves your ability to more easily walk, carry groceries, and climb stairs |

Pain |

↓ Small to moderate |

Improves flexibility and reduces pain and stiffness in your joints |

Quality of life |

↑ Moderate to large |

Adds to a sense of well-being and your willingness to engage more fully in life |

Physical Inactivity

The scientific evidence is clear: being sedentary is lethal. Physical activity means movement of the body that expends energy. Walking, climbing the stairs, and dancing the night away are examples of being active. Regular physical activity lowers blood pressure; helps maintain healthy bones, muscles, and joints; and promotes psychological well-being. Benefits also include a significant reduction in the risk of cardiovascular diseases, hypertension, obesity, diabetes, several cancers, and depression.

Despite the well-known benefits of being active, researchers find that the number of physically inactive men (who engage in less than a few occasions of 30 minutes of activity per week) has been increasing. One series of studies in the United Kingdom revealed that two-thirds of men didn’t meet the minimal target for physical activity (30 minutes of moderately intense activity for 5 or more days a week), and there is a noticeable reduction of physical activity around the common retirement age, 65–74.7 The patterns in the United States are similar.8 The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Healthy People 2020 project, started in 2000, shows that 40 percent of adults engage in no leisure-time physical activity, and only 15 percent perform the recommended 30 minutes per day, 5 days a week of physical activity. The proportion of adult men engaging in no leisure-time physical activity has increased to nearly 50 percent, and the American Heart Association estimates that half of men age 65 and older are “sedentary,” or physically inactive. These statistics are “red flags” warning us that too many men are not adopting healthy habits.

While aging and age-related changes in functional ability likely force a number of men into less activity, men do or do not participate in exercise or physical activity for many personal reasons. Men are often motivated to engage in physical activity because we feel enlivened and inspired by it. There is a robust association between self-perception/self-image and being physically active. Being active is an opportunity to perform or compete and gain validation and recognition. Throughout our lives we develop a sense of pride in our physicality, and physical activity is synonymous with showing that the body remains fit.

I think as long as you exercise and can do as much as you can and the best that you can, then it’s all you can do. I mean, even gardening. At least then you feel like your body is working. It feels like you have done something, and that makes you feel good.9

Most men who are physically active develop a routine or “habit” that includes physical activity. Rarely are we motivated to participate in types of physical activity and exercise because of the health benefits. Rather, we are physically active because of factors such as fun, enjoyment, camaraderie, and socializing with friends. The positive effect is the earned sense of achievement and the social support men gain from their participation in physical activity.

Barriers to physical activity range from the simple pragmatics of poor access, to time constraints and high costs, to complex issues relating to identity. Self-perception is terrifically important in motivating men to participate in any type of physical activity.10 Some men do not want to walk alone, wary of the stigma of being thought of as loners, but runners and cyclists and swimmers often prefer being out by themselves to enjoy the solitude. The anxiety about not “fitting in” because of one’s unfamiliarity and/or a lack of confidence about entering unfamiliar spaces such as a pool or the gym culture or the group that is line dancing are serious barriers leading to some men’s lack of participation in physical activity. But the biggest barrier is the set of lifestyle habits already in place that make adding time for getting active a challenge.

YOUR LEVEL OF ACTIVITY

Excess body weight is chiefly a result of an imbalance between energy intake and energy expenditure. Physical activity is energy expenditure. When energy expenditure is equal to energy intake, your body weight will be maintained. If you are a bit overweight and keep your energy intake on par with your energy expenditure, you will remain a bit overweight. It is the proportion of calories eaten (energy intake) to the level of physical activity (energy expenditure) that determines our weight gain or loss.

Casual surveillance of the U.S. population reveals that many people seem overweight (and out of shape). Research shows that nearly three-fourths of men age 50 and older are carrying excess body weight.11 The fact is, 4 out of 10 of those men are also “sedentary”—they take part in no exercise whatsoever. We have been told for years that inactivity and carrying extra weight can lead to unwanted and troubling health problems. But most adult men live with these risks. We have not yet reclaimed enough time for ourselves and used the time to be physically active. However, it’s our physical activity decisions that will have greater impact than just changing our eating habits. The bulk of the weight gain in older men is also because of our body’s slower metabolism, and in order to counteract this effect of intrinsic aging, men must crank up their metabolism by getting and staying active.

To identify your current level of physical activity (or energy expenditure), use these guidelines:

Sedentary. You sit most of the day and find that you rarely move around, whether it is at work or at home. Your work has you sitting in a truck or in front of a computer; and when you’re home, you cut the lawn with a tractor mower, are in front of the television, or are in a chair reading the newspaper. You are sedentary. This lifestyle is a serious risk to a man’s health, especially as we get older, and it almost always leads to weight gain. You are not burning the calories you take in.

Sedentary. You sit most of the day and find that you rarely move around, whether it is at work or at home. Your work has you sitting in a truck or in front of a computer; and when you’re home, you cut the lawn with a tractor mower, are in front of the television, or are in a chair reading the newspaper. You are sedentary. This lifestyle is a serious risk to a man’s health, especially as we get older, and it almost always leads to weight gain. You are not burning the calories you take in.

Light. Light activity includes some movement, like sanding and painting a window, a teacher who moves about the classroom, gardening, or strolling around a few blocks while talking about the events of the day or walking your dog. Do you see yourself leaning on the cart while walking throughout a “big-box” store (such as BJs, Super Walmart, Costco), instead of walking upright and pushing the cart in front of you? While this is certainly better than being sedentary, and while it does begin to lower the risks of ill health, light activity will not combat the ordinary weight gain that comes with lower metabolism.

Light. Light activity includes some movement, like sanding and painting a window, a teacher who moves about the classroom, gardening, or strolling around a few blocks while talking about the events of the day or walking your dog. Do you see yourself leaning on the cart while walking throughout a “big-box” store (such as BJs, Super Walmart, Costco), instead of walking upright and pushing the cart in front of you? While this is certainly better than being sedentary, and while it does begin to lower the risks of ill health, light activity will not combat the ordinary weight gain that comes with lower metabolism.

Moderate. Moderate activity is generally the ideal and includes activities such as brisker walking, skiing, slow jogging, and swimming. Think about the UPS or FedEx driver who zips up in a truck, walks the package to the address, and walks back to the truck. The walking the driver does daily is more than most of us do. To achieve this preferred level of daily activity, we need some heart-pumping activities. You might consider a greater number of minutes of walking every day, pulling your golf clubs and walking the course rather than riding in a cart, hiking a mile uphill on a trail and comfortably walking back, or parking the car anywhere and walking at a good clip for a mile.

Moderate. Moderate activity is generally the ideal and includes activities such as brisker walking, skiing, slow jogging, and swimming. Think about the UPS or FedEx driver who zips up in a truck, walks the package to the address, and walks back to the truck. The walking the driver does daily is more than most of us do. To achieve this preferred level of daily activity, we need some heart-pumping activities. You might consider a greater number of minutes of walking every day, pulling your golf clubs and walking the course rather than riding in a cart, hiking a mile uphill on a trail and comfortably walking back, or parking the car anywhere and walking at a good clip for a mile.

Heavy. Heavy activity is similar to moderate, only revved up a bit. It builds strength and muscle tone, stronger bones, and stamina; improves blood chemistry (including high-density lipoprotein [HDL], the “good” cholesterol); and eats up calories. The people unloading and loading 20–40 UPS or FedEx trucks each shift are doing the heavy work. So too are men who run a couple miles daily, ride a bike at a good clip, or continue to play a sport. If you find yourself physically able to engage in more strenuous activities like these, go for it. If not, moderate exercise will certainly benefit your health.

Heavy. Heavy activity is similar to moderate, only revved up a bit. It builds strength and muscle tone, stronger bones, and stamina; improves blood chemistry (including high-density lipoprotein [HDL], the “good” cholesterol); and eats up calories. The people unloading and loading 20–40 UPS or FedEx trucks each shift are doing the heavy work. So too are men who run a couple miles daily, ride a bike at a good clip, or continue to play a sport. If you find yourself physically able to engage in more strenuous activities like these, go for it. If not, moderate exercise will certainly benefit your health.

We need to remain realistic about our fitness and take into consideration our age and body type. If you have health limitations, you are advised to slowly increase your levels of physical activity. Resist wanting the electric scooter that advertisers urge you to purchase to make you more mobile. A scooter might make zipping around a grocery store seem convenient, but it is another means to being sedentary. If your current activity level is sedentary or light, the goal is to be more rather than less active.

If you are fit enough to meet the recommendation of 30 minutes of moderately intense physical activity a day for 5 or more days a week, yet not this active, you need a plan. Adding 150 minutes of “exercise” per week may sound overwhelming at first, but this time can be spread out into 10-or 15-minute intervals. Studies show that just 10 minutes of cardio activity provides cardiovascular benefits. So if either time or endurance is a problem, break up your exercise routine into shorter intervals. As you begin to integrate being physically active, and as your endurance builds, challenge yourself to exercise more often and for longer periods of time—you’ll be surprised at the results. But be realistic. Plan to take small steps toward improving your fitness, and reward yourself when you reach them (but not with two added beers).

One older man recommended that you buy yourself a pedometer (step counter) and wear it during your waking hours for a few days to track your physical activity. His comment: “This is your life.” A pedometer, about the size of a pager and worn on the waistband, measures and counts the motion of the hips. This device can be purchased for as little as $10. After a couple of days of recording what you normally do, if you are already within the recommended physical activity levels, great. If not, you now know and the question becomes, are you ready? The goal of healthy aging is to increase our physical activity, beginning with the number of steps taken daily. If you set a personal goal to increase your steps and wear the pedometer, you will likely find that you’ve added 1,000 or more steps within a few weeks. You become conscious of walking and start walking more.

CDC Fitness Recommendations

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention now urges two types of fitness recommendations for men age 65 and over:

1. Moderately intense activity

• 2 hours and 30 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic activity every week

• and on 2 or more of these days, engage in muscle-strengthening activities to keep from losing muscle as you age;

2. Vigorous activity

• 1 hour and 15 minutes weekly of vigorous-intensity aerobic activity (e.g., jogging or running)

• and muscle-strengthening activities on 2 or more days a week that work major muscle groups (legs, hips, back, abdomen, chest, shoulders, and arms).

For the three-fourths of the men who are already overweight, fitness goals ought to include strategies for both greater energy expenditure and less calorie intake. Weight loss needs to be gradual, and you’ll want to consider a target date—what is a reasonable amount of time to reach that desired weight loss? So if you want to drop 10 pounds, many people recommend that whatever target date you choose, double the timetable. You’ll be more likely to be successful. If you think you can achieve your 10-pound target in 4 months, plan on at least 8. Honestly, it takes time to integrate the “exercise” (better yet, fitness) plan into one’s lifestyle and change one’s metabolism, much less modify eating habits. It probably took you several years to add the pounds.

Whatever your current level, can you increase your daily physical activity by 3–5 minutes? If so, within 4–8 weeks you would be accumulating 10–15 minutes of added activity. Look at the pattern, not the dailies. You did 5 minutes one day, and you know you’re up from where you started, even if below the recommended amount. But keep at it. Slowly work up to 5 additional minutes of accumulated activity. As you become more active, try to enjoy it. This feeling may takes weeks or months, but 6 months forward and looking back, you’ve changed your life. As the old adage says, hindsight is 20/20.

For men without health limitations, you are among the men who are advised to participate in 30 minutes of moderately intense physical activity for 5 or more days a week, totaling at least 2.5 hours per week. Moderately intense activity is good “cardio” activity because it gets you breathing harder and your heart beating faster. How do you know if what you are doing is moderately intense activity? It will make you breathe harder and your heart beat faster. As long as you’re doing this activity for at least 10 minutes at a time, you’re tallying the minutes. The daily amount of physical activity can be accumulated in 10-minute stints—walk at a good pace (outdoors or indoors) during a morning break and again at the lunch break, and you’ve chipped away at the minimum daily recommendation.

Getting Serious

Moderate physical activity has major health benefits, yet it is the more vigorous exercise that has the added benefits. A minute of vigorous exercise is about the same as 2 minutes of a moderately intense form of activity—jogging (not even running) a minute and walking a minute tally to 3 minutes. Do this pattern five times and you’ve mixed together 5 minutes of vigorous and 5 minutes of moderately intense exercise, which fulfills the daily minimum recommendation. If you can and do engage in vigorous exercise for 30 minutes, three times a week, this will yield noticeable cardiovascular fitness.

Get Active

Moderate Physical Activities |

Vigorous Physical Activities |

• Walking briskly (about 3½ miles per hour) |

• Running/jogging (5 miles per hour) |

• Hiking |

• Bicycling (more than 10 miles per hour) |

• Gardening / yard work |

• Swimming (freestyle or breast stroke) |

• Dancing |

• Aerobics |

• Golf (walking) |

• Walking fast (4½ miles per hour) |

• Bicycling (less than 10 miles per hour) |

• Heavier yard work, such as chopping wood |

• Weight training (general light workout) |

• Tennis or basketball (competitive) |

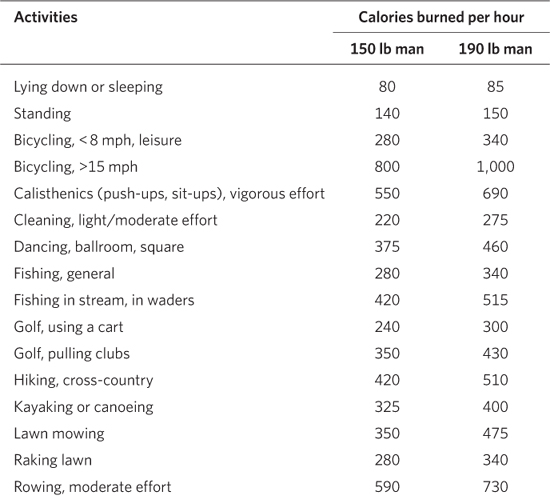

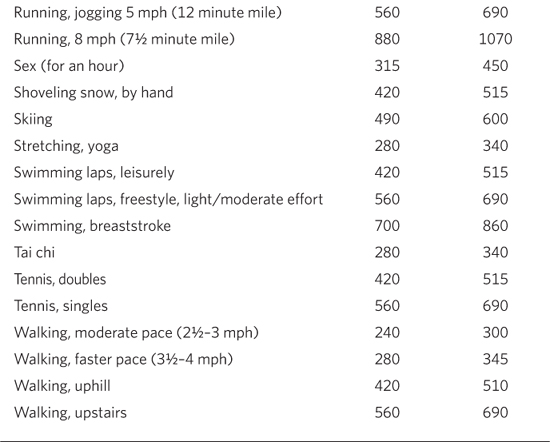

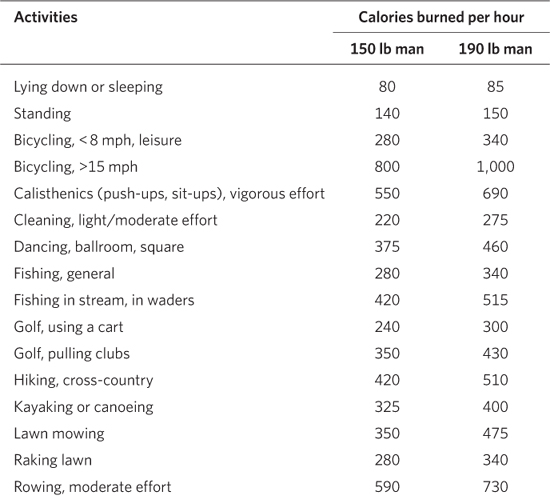

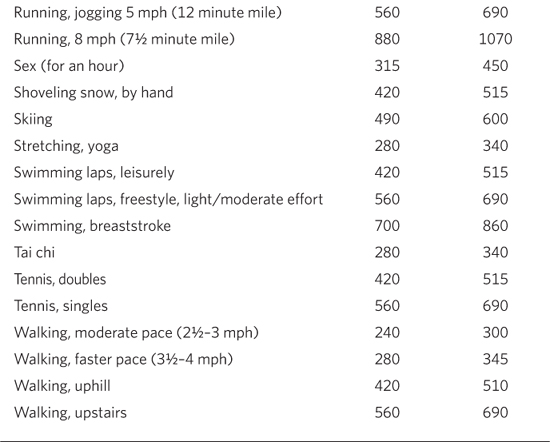

BURNING CALORIES

A long-term commitment to activity is required for building muscle and for weight loss. As we get older, it will take longer to lose the fat (remember—our metabolism slows, and it is metabolism that burns the calories). Because of this, it is recommended that we engage in longer periods of moderately intense physical activity in order to burn calories and to achieve measurable weight loss over a number of months. As tough as it seems to carve out time from our other greedy commitments, we need to crank up our energy expenditure. The current recommendation is that by age 60 we also find ways to engage in resistant exercises (e.g., using weights; stepping on and off a plastic step stool) if we want to combat natural muscle loss. Despite people’s best intentions to lose weight and maintain muscle mass, however, the majority of adult men do not engage in the minimum recommended level of physical activity.12

EXERCISE OPTIONS

If you’ve ever walked into a gym, what are the odds of seeing a 75-year-old working with free weights? Slim you think, because older men did not grow up in a culture that encouraged most men to use a gym. Gyms were for boxing. Nowadays, you are more likely to find two old men working out together. Most health insurance plans provide a partial reimbursement for the cost of joining a fitness center. The healthy aging culture has changed the meaning of “working out,” and there are many types of fitness centers and sport clubs available. Here are a few options to keep you physically active, and each will bring about healthy changes for your body:

Swimming is a great form of exercise because it is easy on your joints and is still a great cardiovascular workout. Recreational swimming is a good way to reduce stress and relax while getting a full-body workout. Doing laps will help build and maintain muscle mass in your legs, shoulders, arms, and abs, as well as increase your endurance. You can swim using a kickboard, and to avoid boredom, people usually switch up the routine by trying different strokes or, if available, swimming in the ocean or a quarry as opposed to a pool. Don’t worry about how you look in a baggy swimsuit; most men over 50 look less than perfect. You’re there for yourself; use the goggles and feel the freedom.

Walking, not strolling slowly along, has aerobic benefits. Two types of walking contribute to long-term improvements in cardiorespiratory fitness.13 One is moderate intensity, high frequency—walking at a pace that makes you breathe a little bit harder than usual but you are able to keep up a full conversation, and doing this five to seven times a week for 30-minute sessions. The other is high intensity, low frequency—walking at a faster pace three to four times a week for 30 minutes, where you are able to speak only in short sentences and are huffing and puffing a bit.

The elliptical and rowing machines found in nearly all “workout” rooms in hotels, gyms, YMCAs, and school athletic facilities are other good choices because they tend to be low intensity—meaning that you are not pounding on your feet and knees. These machines are smart choices because they are easily adjustable to your physical needs. If you are just starting to exercise, for example, you can have no resistance and a low incline, whereas more experienced users can crank up the resistance to make for a more intense workout.

Bicycling, or cycling, is a great alternative to running because it gets you feeling independent and is a little more relaxing while also a fantastic workout. It not only enables you to enjoy scenic places but also goes a long way to ensuring your overall fitness, especially heart health. Biking is an especially valuable option for people just getting back into an exercise routine, because it is easy to adjust your level of difficulty—with both the gears on the bike and your chosen paths. For men who are carrying added weight, cycling can prove to be very beneficial, for it helps in getting rid of the increased waistline. Check out local parks for bike routes in warm weather, or try a stationary bike in the winter and time yourself by watching a half hour of television. You can convert your own bike into a stationary bike at a modest cost. The best part about this activity is that you can find cycling a delightful experience, without even realizing that it is doing good things for your body.

Playing tennis is an awesome way to exercise14 and be with friends. It is a sport that will certainly increase your cardiovascular endurance and strengthen muscles. You typically burn more calories playing tennis than you will by swimming and biking. It is an exercise that involves “anaerobic” fitness—meaning that you are engaged in short, intense bursts of activity followed by periods of rest, and this helps muscles use oxygen more efficiently. If you don’t have a tennis partner, find a court with a wall and make it your 20- to 30-minute partner. This is the way many racquetball and handball players warm up or practice. Most elementary and middle schools also have hardtop surfaces running up to a solid wall that will not be damaged by your tennis ball.

Strength training and muscle strengthening become more important as we get older, because of our lower levels of testosterone and declines in muscle mass. Strength training involves pushing yourself to a point where you feel the “burn.” One example of doing a simple workout is to use a solid four-leg chair and slowly lower yourself, but do not actually sit. Instead, just before your butt touches the chair, slowly stand up, and repeat this up to eight times. This exercise works multiple muscle groups (legs, hips, back, abdomen). Then, do at least 20 push-ups from a wall (or the floor). This simple indoor exercise plan works a range of different muscle groups, and you will notice the benefits after 6 months. You’ll find that it takes increasingly longer workout sessions to feel the “burn.”

SHOULD YOU SEE A PHYSICIAN BEFORE YOU EXERCISE?

Whatever we do for physical activity, not injuring ourselves is the number one goal. In competitive over-50 sport leagues, the rule of thumb is, “Do not hurt yourself. Playing is more important than sitting.”

If you find yourself generally healthy—you do not have any life-threatening illnesses, your body doesn’t have any unusual aches or pains, and you feel capable—it is unlikely that you need to consult a physician before you start working out. That being said, seeing a doctor is never a bad idea, especially if you have specific goals in mind or have any kind of history of medical problems.

The time when you should certainly see a doctor is if you have any preexisting illnesses, especially ones related to your heart. As important as exercise is, there are some circumstances where it can be harmful, especially if you push yourself too hard and your heart is unable to handle the challenge. Seeing a doctor will establish first and foremost whether you should be exercising at all and, secondly, what exercises are appropriate given your health.

Whether you are in peak condition or just starting out, if you experience dizziness, shortness of breath without overexertion, chest pain/discomfort, or anything else that doesn’t seem right with your body, stop working out! Speak with a doctor. It may seem like nothing, but avoiding medical attention when it could be needed can make easily resolvable problems much more serious and significant.

MUSCLE FATIGUE AND MINOR INJURIES

As much as exercise and diet are essential to strengthening and maintaining muscle, did you also know that resting muscles is considered equally important? During taxing physical activity, muscle fibers are routinely damaged. The damage is temporary, if the muscles have adequate time to rest and recover. Because it takes longer for our muscles to recover from laborious work as we age, it is important to pace ourselves. It is equally important that our diet provide the nutrients that the body needs to repair and rebuild these muscle groups before we again tax them.

Most experts suggest 48 hours of recovery time in order for a particular muscle group to fully repair after resistance training or some other muscle-taxing activity. This is the reasoning for only 3–4 days weekly of high-intensity exercising. However, this does not mean that you should only exercise every 3 days. By rotating which muscle groups you use during a particular routine, you can isolate certain muscle groups while letting the others repair and rest. Adding variety to your exercise routines will ensure that your muscle groups have enough time to recover and keep your routine exciting.

Caution: Snow Shoveling

Heart attacks, back strain, and muscle soreness are just a few of the problems associated with shoveling snow. Snow shoveling is very demanding on the body. What makes shoveling more dangerous than other average tasks around the house is the temperature. Your heart rate and blood pressure increase during strenuous activity. Add the body’s natural response when exposed to the cold—constricting arteries and narrowing blood vessels—and you have a perfect storm for a heart attack. If you shovel for 30 minutes, you’ll burn 200–250 calories.

In order to minimize the frequency and effect of the injuries, follow the principles of the PRICE (protection, rest, ice, compression, and elevation) method of treating minor injuries. Not surprisingly, the first step is protection. If you know that a certain body part is hurt or weak, do not overuse the muscle and, if possible, use a wrap or brace during exercise to give the area more support and minimize your risk of injury. There are all types of knee, ankle, wrist, and elbow protective “wraps” commercially available. In addition, you’ll likely need sunglasses if you are rowing; swimming goggles if you are heading to a quarry or pool; new shoes that have the needed support inside for any walking, running, or hiking; or protective gloves and eyewear for other activities. Notice how professional golfers always have hats or caps to protect their eyes, as well as a driving glove; that glove isn’t just to grip the club, it’s to prevent soreness. Men planning on cycling will surely need a helmet and a brightly colored shirt/jacket to make them visible to motorists.

After you have a muscle, bone, or joint injury, you need to take some time off from your physical activities to allow your body to recover. Once you do sustain an injury, rest the body part, and do not resume activity until it is healed. Icing (not heating) the injured body part for 15 minutes helps to reduce tissue swelling and inflammation around the injured area. Ice should be put on an injury as soon as possible, and putting ice on early helps the injury heal faster. It’s best to wrap a plastic bag of ice in a thin towel before icing the injury. If ice is not available, use a bag of frozen vegetables. Applying some type of compression wrap or bandage also may be needed to help reduce inflammation. Lastly, elevate the injured part above the level of your heart, so as to prevent blood from pooling at the affected area.

The probability of becoming injured, as well as the recovery time that minor injuries necessitate, seems to increase with age. Any type of taxing physical activity increases the risk of sustaining a nagging injury and can prolong recovery time. If you find that a minor injury is interfering with your exercise routine, incorporate a different activity that uses other muscles. This way, you can stay on track with your fitness program, without stressing the injured body parts. For example, if you sustained a shoulder injury while playing tennis, try riding the stationary bike or swimming using a kickboard. If your injury was caused by resistance training in a gym, take a break from the weights and just stick to cardio until you’re healed. Men who are just beginning to develop a physical activity plan need to pay attention to how their body is “talking back”—to distinguish between feeling the “burn” and symptoms of developing injuries.

EXERCISE AFTER 70?

“What’s the point?” you ask. You might just be surprised. Throughout our lifetime, it is always easy to find excuses not to be physically active and stay fit. Work, family, social events, and hobbies all frequently take precedence over time we need for exercise, which is so easily thrown on the back burner if it is not as enjoyable as other activities. Perhaps the most important barrier to physical activity is a belief that it is too late, or that in order to get the benefits you seek, you must exercise vigorously every day like an athlete. The tendency to believe this myth increases with the lack of physical activity, to the point where taking a walk seems harder and harder to do.

Almost all older men can benefit from additional physical activity. Men who start working out at age 70 can increase their life span by 12 percent—that’s right, starting to work out at 70 can add 8 years or more of independence. The men age 70 and older who were studied in clinical trials were not the ones who did a triathlon until the age of 60, nor were they “ex-athletes” who have forever been into fitness. They were average men, maybe like you, who were able to optimize their aging and lives.15 Becoming active even after age 70, without previously being in shape, sharply increases our odds of remaining functionally independent and not becoming frail. Getting active, no matter your age, increases the length and the quality of your life. We always have something to gain by putting our body in motion, and odds are we will find several companions and enjoy the social time together, too.

Staying Active after 70

A 71-year-old man who has moderately well-controlled hypertension and osteoarthritis of both knees and the right hip is active in two bowling leagues and enjoys walking, but both activities are becoming limited by pain in his knees.

His physicians recommended that he will benefit from increasing his level of activity and incorporating resistance training into his exercise routine. The man began cross training with non-weight-bearing activities of swimming and biking three times per week. He was encouraged to wear good athletic shoes and may benefit from bracing and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medication (e.g., ibuprofen).

Source: Nied, R. J., & Franklin, B. (2002). Promoting and prescribing exercise for the elderly. American Family Physician, 65, 419-427.

“FRINGE BENEFITS” OF EXERCISE

In addition to promoting physical well-being, numerous studies report that exercise and other health-conscious behaviors are closely linked to a positive body image and self-evaluation and to a more optimistic outlook on life in general. This positive self-image is partly due to the physical results of being healthy and feeling “fit,” and partly due to feelings of satisfaction that result from the exercise itself. We develop a sense of self-efficacy through exercise, which promotes overall mental and physical health.

Why? As you exercise, your body releases “feel-good” brain chemicals called endorphins. They are released from the pituitary glands to parts of your brain during physical activity and serve to elevate your mood. As neurotransmitters, endorphins lead to feelings of euphoria and the so-called runner’s high. Researchers find that endorphins also act as natural pain relievers. Not only will exercise improve your physical health, but it positively affects your emotional well-being as well.

Sedentary. You sit most of the day and find that you rarely move around, whether it is at work or at home. Your work has you sitting in a truck or in front of a computer; and when you’re home, you cut the lawn with a tractor mower, are in front of the television, or are in a chair reading the newspaper. You are sedentary. This lifestyle is a serious risk to a man’s health, especially as we get older, and it almost always leads to weight gain. You are not burning the calories you take in.

Sedentary. You sit most of the day and find that you rarely move around, whether it is at work or at home. Your work has you sitting in a truck or in front of a computer; and when you’re home, you cut the lawn with a tractor mower, are in front of the television, or are in a chair reading the newspaper. You are sedentary. This lifestyle is a serious risk to a man’s health, especially as we get older, and it almost always leads to weight gain. You are not burning the calories you take in.