HELPING OTHERS THROUGH DIFFICULT TIMES

The vast majority of families take care of their own during times of need. Years ago, certainly because of the lack of alternatives, families relied on one another as first-line supporters. Even now, we rely on our family well before we turn to health professionals or other service providers for assistance. The eventual call from our families to provide assistance has increased quite a bit in the past few decades, and it is certain to continue to grow simply because we are all living much longer. As men’s and women’s life spans have increased, we are now living with disabling illnesses that people never had before (such as dementia, osteoporosis, postmenopausal breast cancer, cardiovascular disease). With longevity comes a greater number of older individuals who have chronic health problems and need some measure of care—and the call has gone out to men to be caregivers. Nearly everyone will become a caregiver at some point in life—it’s natural, expected, and virtuous. More men are taking on this responsibility.

There are only four kinds of people in this world. Those who have been caregivers, those who are caregivers, those who will be caregivers, and those who will need caregivers.

—Rosalynn Carter, former First Lady

Traditionally, women shouldered the lion’s share of responsibility of caring for family and neighbors. When relatives have asked “Who will care for me?” the answer has most likely been wives, daughters, granddaughters, and other women who came forward and lent a hand. Although women still provide 60–66 percent of the aid, being male and helping someone in need of assistance are not contradictory terms. Each and every day, millions of husbands, gay partners, sons, sons-in-law, uncles, brothers, male friends, and other men take care of family, friends, and other older adults who are frail or not well. The math is simple—if 60–66 percent of caregivers are women, then 34–40 percent are men.1

According to an estimate by the National Alliance for Caregiving, more than 65 million people in the United States provided unpaid care to a friend or member of their family who was chronically ill, disabled, or frail.2 On any given day, there are almost 22 million men who have taken on the responsibility of providing some assistance for a relative, friend, or neighbor who is having difficulties managing alone. The average man who finds himself helping someone in need will do it for approximately 4 years (just as long as a woman), is 47 years of age, is caring for someone who is 77 years of age, and is likely caring for a parent, usually his mom. Beyond the call for the natural “horizontal caregiving” that husbands and gay partners provide to someone of their same generation, there has been a 600 percent increase in the number of sons who provided care to a parent since the mid-1990s, and now one in six adult sons are caregivers.3

Men quite commonly come to the aid of their spouses and partners. These men tend to be older (most likely in their fifties or older) and transition into caregiving. It is what you do for your wife or partner when you have been in a long-term relationship—in that sense, caregiving is an extension of living together and sharing a home. You slowly and incrementally increase your hours per week preparing meals, cleaning, shopping, doing laundry, and eventually assisting with some of the “body work” such as bathing and dressing. You might not even perceive yourself as a caregiver, but you are. Spousal caregivers are more likely retired; however, a sizeable number, perhaps as many as 25 percent of men caring for their wives, tackle the responsibilities of caregiving while simultaneously dealing with the demands of part-time or full-time employment. These men are commonly caring for a spouse or partner suffering from a disabling disorder such as chronic heart failure or Alzheimer’s disease and have to deal with the special challenges that accompany helping someone gradually deteriorating physically and cognitively. If you are one of these caregivers, the demands placed on you can be especially great.

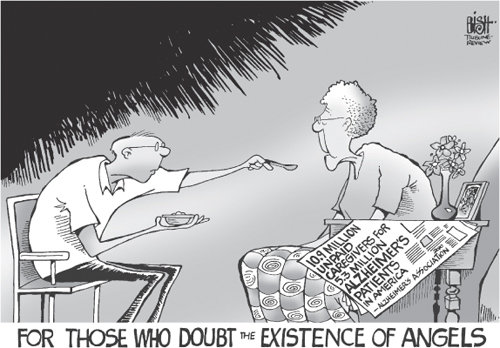

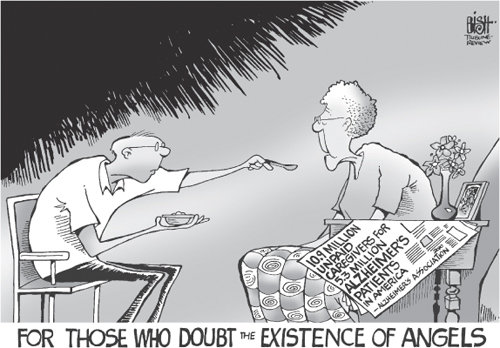

From R. Bish (2010, Oct. 7). Caring for Alzheimer’s patients. Pittsburgh Tribune-Review.

As an example, there are nearly 15 million Alzheimer’s and dementia caregivers providing 17 billion hours of unpaid care annually. At least 40 percent are men.4 Because Alzheimer’s disease is more commonly diagnosed in women and requires high levels of care, and because the majority of women with dementia live in the community, many men find themselves stepping up and performing the role of caregiver, something they never anticipated.5 You need to know that men who are caregivers generally, and particularly those who are Alzheimer’s caregivers, suffer enough emotionally and physically to be called the “silent victims,” because caregiving is extended in duration, sometimes 24/7, and the person being cared for slowly ceases to exist—their personality, behavior, and memory change dramatically and they become increasingly dependent on someone else to care for them. Men may well be less distressed than the women who embodied care work (at least on the various ways social scientists measure caregiving stress and burden); however, while husbands providing care for Alzheimer’s wives view the symptoms of this disease to be a less problematic condition and normalize their wife’s deterioration,6 they still report high levels of distress and symptoms of depression.7

What is a caregiver (for example, to a wife)? There are two dimensions: First, you are actually providing her with the help needed to remain as healthy as possible, which means you are providing food, getting her to take her medications, and perhaps bathing and dressing her. You also are “being there” and providing her the emotional TLC she needs. Second, you take on full responsibility for all the household chores and other things she used to do—from changing the sheets and doing the laundry, to writing notes in birthday cards to children and friends, to shopping, cooking, and managing all the financial matters.

Men who are caring for a parent may not provide 24/7 care, but they provide help an average of 17–18 hours a week while at the same time usually holding down a full-time job. These so-called vertical caregiving relationships that cross generations are no longer unusual. Some sons (or sons-in-law) appear to make caregiving a second career, committing 30, 40, and 50 hours or more a week to these efforts. These younger caregiving men tend to live farther away from the person they are helping and, as a result, have to travel farther and spend more time organizing care that is provided when they are not on hand. Men who provide care from a distance find using outside services particularly helpful, especially when it comes to meeting the transportation needs of loved ones and handling their personal care needs (help with dressing, bathing, personal hygiene). Long-distance caregiving sons generally also make heavy use of the Internet as a source for finding resources they may need to help them in their responsibilities as the caregiver.8 As Eleanor Ginzler reminds us, what is perhaps most important is that while the men who become caregivers are fewer in number, they are equal to women in terms of their dedication to the task.9 In the rest of this chapter we consider the experiences and responsibilities of middle-aged and older men helping others, or caregiving, as it will be termed here.

So what does it mean to be a caregiver? It is likely that many men who are reading this chapter have already assumed the role of informal caregiver to some degree. If married or partnered, you have roughly a 50–50 chance of performing some, if not all, of the functions of a caregiver during your lifetime. So why do news analysts, some academic researchers, and so many relatives and friends assume that men are not the caregiving kind? Well, likely that can be traced back to traditional gender stereotypes, namely, the tendency to characterize men as rough brutes, unwilling and unable to express themselves as loving and caring individuals.10 That perception is longstanding, widespread, and an extremely difficult mentality to alter. Yet men who are caregivers prove the stereotype wrong, day in and day out. They might adopt more of the instrumental approach that can segment the nuts and bolts of care work into “work” from the enjoyable time providing “care,” yet as caregivers men readily do the expected care work and they care.11

Don’t be surprised if one day you need to consider discussing your caregiving responsibilities with your employer and perhaps agree on certain adjustments in your work pattern such as changing your hourly schedule or shifting from full- to part-time employment. It could mean that you need to leave work early on occasion or arrive late. These can be difficult discussions to have with your supervisor or manager, especially if you think that they may not be particularly understanding or willing to accommodate your needs. Employers very often do not comprehend that their male employees need “family time.” Other men, because of “male pride,” may not want to admit that they are finding it difficult to juggle the competing demands that exist in their work and personal lives and elect instead to hide this from their work colleagues. Either way, there is little to be gained by not making the effort to negotiate a healthier balance between work and your caregiving responsibilities.

Stoic pride and/or hesitation to make every effort to plan a more manageable work/family arrangement can easily backfire on you, leading to consequences that include poor performance, lower productivity, and more distress over the caregiving responsibilities awaiting you at home. These two-pronged, snake-bite consequences could ultimately lead to a negative performance evaluation at work and premature burnout as a caregiver at home. The majority of men who make the effort to adjust aspects of their work life to meet the demands of caregiving are able to do that.

Over 8 in 10 men caregivers in the United States were employed full- or part-time when they were caregiving in 2009, and among these employed caregivers, two-thirds report that they have gone in late, left early, or taken time off during the day to deal with caregiving issues; one in three have altered their work-related travel, and one in five indicate they needed to take a leave of absence.12 These employed caregivers are older and more likely to perform blue-collar work.13 What policies and resources are available to those men who are employed and carry caregiving responsibilities at the same time?

In 1993 an important piece of federal legislation was enacted that supports the efforts of family caregivers. The Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) requires that covered employers provide up to 12 weeks of unpaid leave for eligible employees who have family and medical obligations requiring that they devote time at home to care for a family member in need, be with them during a medical emergency, or arrange for services provided by others. The U.S. Department of Labor website (www.dol.gov/whd/fmla/) provides you with full details about the FMLA, including all the regulations and eligibility rules and a variety of fact sheets. States have also enacted similar such laws extending the coverage to a more broad range of employees, as well as, in some cases, allowing for partial paid leave for family-related needs.

You should inquire into what caregiver information and resources might be available through your employer’s human resources or employee assistance departments. Some employers will also work with you to modify your work schedule in order that you can more easily tend to the needs of those you are helping at home. You can find information on workplace programs, legal/financial issues, online discussion groups, and more from the Work and Elder Care section of the Family Caregiver Alliance’s National Center on Caregiving.

Caregiving can be taxing work—physically, mentally, and financially. It is not unusual for men who are caregivers to report significantly lower levels of life satisfaction and losses of freedom to take a walk or drive or pursue social activities with friends. And these men caregivers are likely to feel that their care work is unappreciated by other family members. This appears to be especially the case for those men who are the sole or primary caregiver rather than a secondary caregiver. That is to say, for those men who are the only one providing help or the one providing the lion’s share of the help, being the caregiver can be expected to be more demanding. Men who are the sole or primary caregiver are also more likely to rate their overall health (physical, functional, mental, and emotional) lower. It is also not particularly unusual for these men to say that their lesser health curtails some of the care they are able to provide. This appears to be especially the case for caregivers who are older, have serious health problems, survive on lower incomes, perform more caregiving tasks, and care for more severely disabled persons.14

Take Care of Yourself

• Learn to use stress-reduction techniques

• Attend to your own health care needs

• Get proper rest and nutrition

• Exercise regularly

• Take time off without feeling guilty

• Participate in enjoyable activities

• Get help from others

• Seek supportive counseling when you need it

• Identify and fess up to your feelings

• Try to be positive

• Set goals for yourself

Source: Family Caregiver Alliance, National Center on Caregiving.

Describing the physical and emotional demands of caregiving is done not to dissuade you from carrying out the responsi-bilities of being a caregiver. Rather, it is done to encourage men generally, and spousal/partner caregivers in particular, to make a concerted and continuing effort to take care of themselves. You will ultimately be of little benefit to those in need of your help if your own health needlessly suffers. Too many caregivers find themselves sleep deprived, saddened if not depressed, using more medications, psychologically distressed, and suffering from new physical health problems because they did not tend to their own needs in a timely fashion. Still others suffer premature caregiver burnout because they did not seek help early enough. Warning signs of caregiver burnout include loss of energy, lowered resistance to colds and the flu, constantly feeling exhausted, neglecting your own needs, not finding satisfaction in the help you are providing, finding yourself unable to relax, feeling impatient and irritable, and feeling overwhelmed, helpless, and even hopeless.

Alzheimer’s Caregiving

For ten years, A.B. shepherded his wife, Frances, through the dark maze of Alzheimer’s disease. … He was there through the early stages, when they laughed over Frances’ locking her keys in her car, or forgetting a friend’s name. But slowly the signs became unavoidable. Always the trusted copilot on their frequent road trips, Frances could no longer read a map. Once a master gardener, Frances slowly abandoned the hobby. The landscaping on their Grant, FL home soon deteriorated to bland, basic upkeep.…

All the responsibilities Frances had maintained through nearly 60 years of marriage—paying bills, making appointments, housekeeping, cooking—fell to A.B., now 82. He accepted his new role without complaint, even as he found himself feeling less like a partner in a marriage and more like a father parenting a child.

Source: Ramnarance, C. (2010, Sept. 13). Till dementia do us part? As a spouse is stricken with Alzheimer’s disease, more caregivers seek out a new love. AARP Bulletin.

It is important to remember that the vast majority of men who care for others do it well. Most men who are caregivers approach their tasks with an attitude that caregiving is their responsibility and brings them considerable emotional gratification. These men do it regardless of how much strain it can add to their own personal and professional lives. However, while not unusual statistically, caregiving can be a precarious situation. It might lead others to question whether you are taking advantage of the person you care for; there is also the potential for unintentionally mistreating the person you are responsible for. Skeptics might think that sons are caring for a parent in hopes of collecting inheritance, or if a son moves back to his parents’ home to care for his frail mother, people may assume he is just “sponging” off the parent. There are just enough cases where care recipients are subject to instances of mistreatment in the form of exploitation, neglect, and abuse. Whether you are a husband, partner, son, brother, or other male relative, the person you care for is, by definition, vulnerable. Because her capacity is necessarily compromised, if you take her out for a drive, stopping to run in the grocery store and letting her stay in the (hot) car, you might return to find a police officer wanting to know why you left this older person locked in the car. Worse yet, she may have Alzheimer’s disease and wander off on her own. Both scenarios put you in the position of being judged by others for neglecting her. Unfortunately, the facts support others’ wariness—the vast majority of those who abuse, neglect, or exploit care recipients are relatives rather than strangers.

Periodically a well-known personality brings to light the disturbing consequences of elder abuse. During spring 2011, veteran actor Mickey Rooney disclosed his experience of being emotionally blackmailed and financially exploited by his stepson. Ninety-year-old Rooney, in testimony before the Senate’s Special Committee on Aging, pointed out that “if elder abuse happened to me, Mickey Rooney, it can happen to anyone.”15 He described being intimidated and bullied, having his access to mail blocked, being deprived of food and medications, having his money taken and misused, and not being allowed access to information about his finances.

Cases like this reveal the too-frequent reality about some men caregivers’ horrific behavior, and what they do tarnishes the reputation of all men who unwaveringly provide care and love to a dependent older adult.

If you occasionally find your stress or anger reaching dangerous levels, call someone. Remove yourself from the situation if only temporarily, by finding respite. If you raised children, you know that it is better to walk away from a situation and cool off. Should others think that you are mistreating the person you are caring for, they are obliged to report it.

The most significant struggle men caregivers face is coping with the isolation.16 A seemingly obvious step to ease the isolation and the demands of caregiving is for you to enlist help from other members of your family and your friends and neighbors. The responsibilities of caregiving are much more manageable when you are not the sole caregiver and share the tasks with others. When sharing caregiving tasks with one or more other people, it is advisable for those involved to determine who is best prepared to perform particular responsibilities.

As obvious as asking for help may seem, you might find it difficult to do. Often men’s drive toward self-sufficiency blocks the logic of asking others to help. Research shows that some men caregivers are considerably less likely to ask for assistance from family or friends and from community organizations. They were raised to “tough it out” and handle things on their own no matter how difficult the situation might be.17 Unfortunately, this stiff-upper-lip mentality can be injurious to your well-being.

Men need time with friends (and more than e-mail time) to receive the emotional support we can get “hanging out” together over breakfast or a card game.18 Family team work and reaching out to your local Area Agency on Aging (AAA) for in-home services will make the tasks of caregiving much more manageable and less stressful for everyone concerned. A successful family caregiving team needs to agree in advance who will do what. Whenever possible, the assignment of tasks should be based on the abilities and interests of each member of the family team, as well as a realistic appraisal of how much time each person has available to volunteer to help.

Quiz for Caregivers

Knowing your and other caregiving team members’ strengths and limits cannot be captured any better than the questions suggested by the National Institute on Aging.

When reflecting on your strengths, consider the following:

• Are you good at finding information, keeping people up-to-date on changing conditions, and offering cheer, whether on the phone or with a computer?

• Are you good at supervising and leading others?

• Are you comfortable speaking with medical staff and interpreting what they say to others?

• Is your strongest suit doing the numbers—paying bills, keeping track of bank statements, and reviewing insurance policies and reimbursement reports?

• Are you the one in the family who can fix anything, while no one else knows the difference between pliers and a wrench?

When reflecting on your limits, consider the following:

• How often, both mentally and financially, can you afford to travel?

• Are you emotionally prepared to take on what may feel like a reversal of roles between you and your parent—taking care of your parent instead of your parent taking care of you? Can you continue to respect your parent’s independence?

• Can you be both calm and assertive when communicating from a distance?

• How will your decision to take on caregiving responsibilities affect your work and home life?

Source: National Institute on Aging (2010, Aug.). So far away: Twenty questions and answers about long-distance caregiving (NIH Publication No. 10-5496), p. 9.

If you live an hour or more from the person who needs care, you are considered to be a long-distance caregiver. There are 7 million or more long-distance caregivers across the country. Caring from a distance can be particularly challenging. You may feel like you are not doing enough or that what you are doing is not particularly important. Yet long-distance caregivers, in particular, may be able to provide important emotional support and periodic relief for others who are the primary caregivers.19 They can also be helpful by staying in touch with the person in need of help by phone or e-mail and by researching online sources of support, managing finances, paying bills, and arranging for services. Another way they can help is with the cost of care.

The National Family Caregiver Support Program (NFCSP), established in 2000 and funded through the U.S. Administration on Aging, provides a range of services to support you if you are a caregiver of someone 60 or older. Their goal is to relieve some of the financial and emotional hardships that are inherent in care work. The services are delivered through the network of AAAs. Contacting your local AAA, you can get the information you need to identify what free and pay-as-you-go services are available in your community. The agency also usually provides caregiver training, can identify men’s caregiver support groups, and offers individual counseling and respite care services on a limited basis. Other services available in most communities can be invaluable added sources of support:

In-home services include homemakers, home health aides, and home attendants who can provide a wide variety of non-medical-related help, such as assisting with a person’s bathing, dressing, or using the toilet; preparing meals; providing transportation; offering companionship; and escorting to doctors’ appointments.

In-home services include homemakers, home health aides, and home attendants who can provide a wide variety of non-medical-related help, such as assisting with a person’s bathing, dressing, or using the toilet; preparing meals; providing transportation; offering companionship; and escorting to doctors’ appointments.

There are meals that can be delivered to the home (frequently by the local AAA) or offered at a group (congregate) nutrition site in some churches, senior centers, senior housing facilities, and community buildings.

There are meals that can be delivered to the home (frequently by the local AAA) or offered at a group (congregate) nutrition site in some churches, senior centers, senior housing facilities, and community buildings.

Examples of Home- and Community-Based Services

• Adult day care programs

• Case managers / geriatric care managers

• Emergency response systems

• Friendly visitor / companion services

• Home health care / home care

• Homemaker/chore services

• Meal programs

• Senior centers

• Respite

• Transportation services

For husbands, sons, and gay men who live with the person they are caring for, there are “respite services” that give you temporary relief and time off from your caregiving. Many men find these services exceptionally important, for it gives them the opportunity to do things without worrying about the care of their wife, parent, or partner. They also provide you with a critical respite, if only temporarily, from the stress and strain of being the caregiver.

Other than a “friendly visitor” coming to your home to be the temporary, substitute caregiver, there is another type of respite service for men caring for an adult who is cognitively impaired (with a dementia) or functionally impaired: adult day care. There are increasing numbers of adult day care programs across the United States (more than 4,600 currently). They represent an important source of temporary relief for caregivers. These programs offer a set of services in a community setting, ranging from some health services to supervised care in a safe environment. Meals and snacks are usually provided, as well as door-to-door transportation. Adult day care centers are generally open Monday through Friday during the day—check out the options in your community. Some programs offer more intensive health and therapeutic services, and some specialize and only serve adults with dementias or other specific disabilities. If you are in a rural community, without readily available community services, be prepared for your caregiving to be more challenging since there will probably not be as many community services available to you.

Watching a loved one battle cancer, dementia, or any other devastating illness can be very difficult. From the fear of losing your loved one, to family worries, to financial concerns, caring can be overwhelming at times. You may find joining groups of other men caregivers to be an agreeable way of seeking companionship and/or help. Caregivers have voices of experience. You all share a common lifestyle, and you can also gain some satisfaction from helping other men. Getting together over a breakfast or lunch, you may be able to gain insight on ways to solve your own problems.20

There are an increasing number of caregiver support groups available to men in communities throughout the United States. These groups may include both men and women or operate exclusively to serve men; some groups are exclusive to men caring for women with breast cancer, or cancer more generally, or to men whose wives and partners have a dementia. Regardless, these groups meet to provide encouragement and an opportunity for members to share their experiences. Typically no referral is required. Groups can be found through local AAAs, disease associations, or online. Online bulletin boards and chat rooms may be perfect for men who have demanding schedules and who want anonymity.

If you are caring for someone with Alzheimer’s disease or a related disorder, the Alzheimer’s Association offers peer or professionally led groups for caregivers. These groups are all facilitated by trained individuals. Many communities offer specialized groups for adult children, men caring for younger-onset or early-stage Alzheimer’s, and husband caregivers with specific needs. The Alzheimer’s Association’s online message boards and chat rooms offer a forum in which to ask your questions and, if you feel so inclined, to share your experiences. Their message boards have thousands of members from around the United States and many more people who simply browse men’s stories and the information that is offered 24 hours a day.

Geriatric care managers are commonly social workers with a master’s degree or professionals in nursing who have demonstrated competencies in helping families who are caring for older relatives. These professionals can help you and the person you are caring for and are often affiliated with a professional care management association. Geriatric care managers are able to help you find needed services and resources in the community which can make your work as a caregiver easier. They can also provide counseling aimed at resolving issues that may be causing difficulties or arguments between you and the person you are helping. Ultimately, the care manager, who is usually paid by the hour for the services they provide, aims to assist older adults with chronic needs, including individuals suffering from Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders, and persons with disabilities in attaining their maximum functional potential. It is recommended that you check to see if the geriatric care manager you want to contract with is a member of the National Association of Professional Geriatric Care Managers (NAPGCM) because they are then guided by an established Pledge of Ethics and Standards of Practice that charge them to act only in the best interests of the person you are caring for.

Contracting a Professional Geriatric Care Manager: Questions You Should Ask

1. Are they a licensed geriatric care manager?

2. Are they a member of the National Association of Professional Geriatric Care Managers?

3. How much experience do they have?

4. Are they available during emergencies, evenings, and weekends?

5. What are their fees?

6. Do they have references?

Source: National Institute on Aging (2010, Aug.). So far away: Twenty questions and answers about long-distance caregiving (NIH Publication No. 10-5496), p. 11.

Elder law attorneys have special expertise in planning, counseling, educating, and advocating for you and/or the person you may be caring for. They commonly deal with personal care planning, including powers of attorney, living wills, wills and trusts, estate planning and tax matters (see chapter 23), and how to protect assets for the caregiver when his loved one requires long-term care.

While the availability of tax breaks is not likely to be the driving force behind why you might become involved in caring for another person, you should know that the help you provide an older adult may qualify as a tax deduction. On average, caregivers spend approximately $5,500 a year providing care,21 and currently there are deductions available to help defray some of those costs.22 Some men may be able to claim the recipient of their care as a dependent and therefore an exemption, which would have reduced their taxable income by $3,800 in the 2012 tax year. To be eligible, you must have provided more than half of the financial support for that person over the past year (this could be a relative living with you or on their own, or a nonrelative who resides in your home). You can still potentially claim the deduction if you are one of multiple individuals who provided the support, as long as your share of the support was at least 10 percent of the care recipient’s annual expenses. In addition, you may be eligible for a dependent care credit as long as the person you care for is unable to physically and mentally care for him- or herself. You may also be able to deduct medical and dental expenses that you paid for the individual if, together with your medical expenses, they exceed 7.5 percent of your adjusted gross income. If you are a single caregiver, you may be able to change your filing status to “head of household,” which will lower your rate of taxation and increase your standard deduction by several thousand dollars.23

There are also federal and state programs that may be able to provide help with the various costs associated with caring for someone at home. Agencies to consult with include the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), which administers Medicare and Medicaid (for people with limited resources); the Program for All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE); and the State Health Insurance Counseling and Assistance Program (SHIP).

While many of the challenges are the same for caregivers regardless of their sexual preference, there are issues of special significance to gay, bisexual, and transgender caregiving men. Gay and transgendered men often do not have the same familial supports to help them construct a caregiving team as they provide care for their partner or a friend. However, many of these men have developed social networks of friends, coworkers, and neighbors, often referred to as “families of choice,” who can assist.24 You might well be one of those friends. Don’t wait to be asked for help; volunteer.

What’s different about LGBT caregiving? Actually, there are more similarities between LGBT and non-LGBT caregivers than differences.25 The differences pivot on heterosexual men not having to confront discrimination. It is important to note that certain policies are beneficial to heterosexual married couples and not supportive of gay (or lesbian) couples or unmarried heterosexual elder couples who live together. The FMLA does not cover same-sex partners; however, some states have FMLA-type regulations that do support taking a leave from work to care for a sick partner. Also, spousal impoverishment policies within Medicaid tend to be financially beneficial to married heterosexual couples but not others, and many state laws deny LGBT caregivers the medical decision-making authority automatically provided to married (heterosexual) couples. It is important for gay, bisexual, and transgendered men to be aware of the local services in their areas, as well as the laws and regulations in their cities and/or states to ensure that they and their loved ones are protected. The National Resource Center on LGBT Aging has launched an interactive, multimedia, Internet portal focused on caregiving resources for LGBT caregivers, including legal and financial issues, HIV/AIDS, and housing and health care access.

For those men who have been involved in caring for a child with serious mental illness such as bipolar disorder or schizophrenia, you are no doubt aware that the challenges can be great. The demands associated with caring for this family member in fact grow as the child enters adulthood because these men caregivers are growing older themselves and facing their own age-related problems. What is known about fathers’ experiences caring for an adult child with mental illness remains sketchy, since most studies continue to study “parents” and do not distinguish fathers’ experiences from mothers’. In an early study, Jan Greenberg did investigate the differences between fathers and mothers, and he found that fathers saw themselves very involved in the care of their son or daughter, provided a similar amount of caregiving assistance as mothers, yet were not as engulfed or burdened by their care responsibilities as mothers.26 There are good resources available to assist these parents, especially from the National Alliance on Mental Illness and one of its 1,000 or more local affiliates.

A growing number of grandfathers are stepping forward to care for and even raise their grandchildren. Unfortunately, many kinship caregivers, as they are called, do not know others who are in similar situations. Nor are they necessarily aware of the available resources to help make the responsibilities of raising a grandchild easier. This can lead to feelings of isolation and frustration. Even when some support services are available, kinship caregivers often face prohibitive barriers to participation in those programs; as a result, they lack substitute child care.

There is no “typical” grandparent-headed household, other than that two-thirds of the grandparents raising grandchildren are married couples. There are over 1 million grandfathers who are responsible for most of the basic needs of a grandchild.27 Men of all different races report being responsible for grandchildren: 47 percent of these grandparents are white, 29 percent are African American, 17 percent are Hispanic or Latino, 3 percent are Asian, and 2 percent are American Indian or Alaskan Native. One estimate finds that nearly 40 percent of these families live at or below the poverty line, even though close to half have at least one caregiver who is employed.28

When older men find themselves parenting again and doing what is neither typical nor expected for their age, the reality is stressful. These grandfathers are understandably going to have to make some adjustments. There are the schools that must be dealt with, as well as the teachers and guidance counselors who may treat you like a temporary parent, rather than who you’ve become. The men very likely face new health challenges of their own as they adapt to parenting again.

If your grandchild(ren) are staying with you, you need to have a document granting you power of attorney to care for the children. The document authorizes you to make medical decisions and avoid delays in timely medical care. AARP offers a number of helpful resources for kinship caregivers. The Grandcare Support Locator allows kinship caregivers to search for specific types of groups and services in their state or community. Using the free online search form, users are able to search in English or Spanish within their zip code to find services and programs (e.g., child care, health care, respite care, newsletters) or support groups (in-person, telephone support, or online), and they can restrict the search to information most relevant to grandparents raising grandchildren or to grandparents experiencing visitation issues.

This chapter began by emphasizing how supportive and helpful relatives, partners, friends, and neighbors have traditionally been when someone is in need of assistance. Yet the time may come when the level of care needed extends beyond what can be provided by the most caring of men at home, even with the assistance of others and available community services. In those cases, relocating someone you care deeply about to a long-term care facility (e.g., a nursing home or assisted living facility) may need to be considered. This is obviously an extremely difficult decision for everyone concerned and requires thoughtful planning. Arriving at such a decision should involve the person receiving care, to the degree that this person is able to participate in the discussion, and all other people providing you support. Having a professional intermediary, such as a geriatric care manager (discussed earlier in this chapter), can make those discussions easier to manage and ensure that all possible options or alternatives are taken into consideration. Whatever the decision, many men will discover that their caregiving experience does not end when a relative, partner, or friend is admitted into a long-term care facility. In fact, your ongoing caregiving can continue to serve a critical role in easing the potential trauma associated with transition into an institutional setting. Not only will the person you’ve been caring for have that continued contact, but so will you. Your responsibilities change from doing all the care work by yourself to becoming an ombudsman for your loved one—you supervise the care the facility provides, continue to take walks (even if a wheelchair is needed), have frequent or occasional meals together, and enjoy a few moments holding hands while watching a favorite television program. The type of long-term care needed can range from adult foster care settings, where the care work is provided in someone else’s home, to assisted living and continuing care retirement communities.

Serving as a caregiver to an ill or incapacitated relative can represent an important opportunity for you to role model caring behavior for the next generation of caring men. Men interviewed by Kaye and Applegate have suggested that those who served as caregivers were more likely to have other men in the family (e.g., sons) assisting them in their caregiving tasks than women.29 The researchers speculate that men who accept the responsibilities of caregiving have the ability to teach the next generation of potential men caregivers that helping others can be included among the adult responsibilities they assume as members of their family network grow older and less able to manage independently. Maybe this is already happening: in the Asian communities in the United States, 48 percent of people over age 50 are being cared for by men, most often sons, and in other ethnic communities one-third of these caregivers also are men.30

For Louis Colbert, a son and person of color, caring for his mother in her home was a privileged and empowering experience.31 Was it difficult? Extremely so, given her advancing dementia and her worsening physical health. It also caught Louis, as it does many men, by surprise. He was not prepared, and he was fearful and ignorant as to what was expected of him. He didn’t know how to transfer her from the bed to the wheelchair or from the wheelchair to the toilet. The first few months were rough—in his words, “I was a big mess.” He didn’t even think of himself as a caregiver for the first 2 years. But years later, Louis recognizes that he is surprised at what he can do. He has learned self-care techniques and when to ask for help, which is his immediate advice to his fellow caregivers on what they can do to make the experience more manageable.

Whether you become a supportive friend providing just a little care work—driving a friend or relative to chemotherapy, stopping by for coffee and conversation—or a full-time caregiver of a spouse or partner, you will learn a lot about yourself and become well versed in tasks that you may never have been particularly skilled in. You already may be skilled to varying degrees in home maintenance and managing household finances. But don’t be surprised if you learn to be a more informed shopper and consumer, or how to prepare meals for two (not huge ones with too many leftovers) and literally feed your dinner partner what you’ve prepared. While helping someone with their personal care needs (bathing, toileting, dressing) is likely to be particularly difficult, over time men discover that they become more capable and confident in these tasks as well. In addition, men who care for others often discover that they become better listeners and problem solvers—in other words, they tap into their “feminine side” and are both affective and sensitive. That is not a bad thing.