ability-to-pay principle of taxation the principle that TAXATION should be based on the financial standing of the individual. Thus, persons with high income are more readily placed to pay large amounts of tax than people on low incomes. In practice, the ability-to-pay approach has been adopted by most countries as the basis of their taxation systems (see PROGRESSIVE TAXATION). Unlike the BENEFITS-RECEIVED PRINCIPLE OF TAXATION, the ability-to-pay approach is compatible with most governments’ desire to redistribute income from high income earners to low income earners. See REDISTRIBUTION-OF-INCOME PRINCIPLE OF TAXATION, POVERTY.

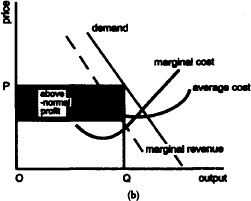

above-normal profit or excess profit a PROFIT greater than that which is just sufficient to ensure that a firm will continue to supply its existing product or service (see NORMAL PROFIT). Short-run (i.e. temporary) above-normal profits resulting from an imbalance of market supply and demand promote an efficient allocation of resources if they encourage new firms to enter the market and increase market supply. By contrast, long-run (i.e. persistent) above-normal profits (MONOPOLY or super-normal profits) distort the RESOURCE ALLOCATION process because they reflect the overpricing of a product by monopoly suppliers protected by BARRIERS TO ENTRY. See PERFECT COMPETITION.

above-the-line promotion the promotion of goods and services through media ADVERTISING in the press and on television and radio, as distinct from below-the-line promotion such as direct mailing and in-store exhibitions and displays. See SALES PROMOTION AND MERCHANDISING.

absenteeism unsanctioned absences from work by employees. The level of absenteeism in a particular firm often reflects working conditions and morale amongst workers in that firm and affects the firm’s PRODUCTIVITY. See SUPPLY-SIDE ECONOMICS.

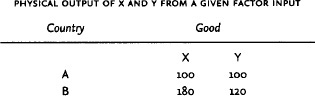

Fig. 1 Absolute advantage. The relationship between resource input and output.

absolute advantage an advantage possessed by a country engaged in INTERNATIONAL TRADE when, using a given resource input, it is able to produce more output than other countries possessing the same resource input. This is illustrated in Fig. 1 with respect to two countries (A and B) and two goods (X and Y). Country A’s resource input enables it to produce either 100X or 100Y; the same resource input in Country B enables it to produce either 180X or 120Y. It can be seen that Country B is absolutely more efficient than Country A since it can produce more of both goods. Superficially this suggests that there is no basis for trade between the two countries. It is COMPARATIVE ADVANTAGE, however, not absolute advantage, that determines whether international trade is beneficial or not, because even if Country B is more efficient at producing both goods it may pay Country B to specialize (see SPECIALIZATION) in producing good X at which it has the greater advantage.

absolute concentration measure see CONCENTRATION MEASURES.

ACAS see ADVISORY, CONCILIATION AND ARBITRATION SERVICE.

accelerator the relationship between the amount of net or INDUCED INVESTMENT (gross investment less REPLACEMENT INVESTMENT) and the rate of change of NATIONAL INCOME. A rapid rise in income and consumption spending will put pressure on existing capacity and encourage businesses to invest, not only to replace existing capital as it wears out but also to invest in new plant and equipment to meet the increase in demand.

By way of simple illustration, let us suppose a business meets the existing demand for its product, utilizing 10 machines, one of which is replaced each year. If demand increases by 20%, it must invest in two new machines to accommodate that demand in addition to the one replacement machine.

Investment is thus, in part, a function of changes in the level of income: I = f(ΔY). A rise in induced investment, in turn, serves to reinforce the MULTIPLIER effect in increasing national income.

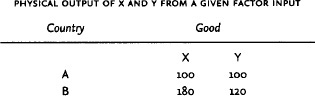

Fig. 2 Accelerator. The graph shows how gross national product and the level of investment vary over time. See entry.

The combined effect of accelerator and multiplier forces working through an investment cycle has been offered as an explanation for changes in the level of economic activity associated with the BUSINESS CYCLE. Because the level of investment depends upon the rate of change of GNP, when GNP is rising rapidly then investment will be at a high level, as producers seek to add to their capacity (time t in Fig. 2). This high level of investment will add to AGGREGATE DEMAND and help to maintain a high level of GNP. However, as the rate of growth of GNP slows down from time t onward, businesses will no longer need to add as rapidly to capacity, and investment will decline towards replacement investment levels. This lower level of investment will reduce aggregate demand and contribute towards the eventual fall in GNP. Once GNP has persisted at a low level for some time, then machines will gradually wear out and businesses will need to replace some of these machines if they are to maintain sufficient production capacity to meet even the lower level of aggregate demand experienced. This increase in the level of investment at time t1 will increase aggregate demand and stimulate the growth of GNP.

Like FIXED INVESTMENT, investment in stock is also to some extent a function of the rate of change of income so that INVENTORY INVESTMENT is subject to similar accelerator effects.

acceptance the process of guaranteeing a loan, which takes the form of a BILL OF EXCHANGE that will be repaid even if the original borrower is unable to pay. This is done by a commercial institution which signs, that it ‘accepts’, the bill drawn up by the borrower in return for a fee. See ACCEPTING HOUSE.

accepting house a MERCHANT BANK or similar organization that underwrites (guarantees to honour) a commercial BILL OF EXCHANGE in return for a fee. See DISCOUNT, REDISCOUNTING, DISCOUNT MARKET.

account period a designated trading period for the buying and selling of FINANCIAL SECURITIES on the STOCK EXCHANGE. On the UK stock market all trading takes place within a series of end-on fortnightly account periods. All purchases and sales agreed during a particular account period must be paid for or settled shortly after the end of the account period.

accounts the financial statements of an individual or organization prepared from a system of recorded financial transactions. Public limited JOINT-STOCK COMPANIES are required to publish their year-end financial statements, which must comprise at least a PROFIT-AND-LOSS ACCOUNT and BALANCE SHEET, to enable SHAREHOLDERS to assess their company’s financial performance during the period under review.

acquisition see TAKEOVER.

activity-based costs see COST DRIVERS.

activity rate or participation rate the proportion of a country’s total POPULATION that makes up the country’s LABOUR FORCE. For example, the UK’s total population in 2004 was 59 million and its labour force numbered 29 million, giving an overall activity rate of 49%. Similar activity rate calculations can be done for subsets of the population such as men, women, ethnic groups, etc.

The activity rate is influenced by social customs and government policies affecting, for example, the school-leaving age and the proportion of young people remaining in further and higher education beyond that age; the ‘official’ retirement age and the proportion of older people retiring early or working beyond the retirement age. Opportunities for PART-TIME WORK and job-sharing can also influence, in particular female, participation rates. In addition, government TAXATION policies can also affect activity rates insofar as high marginal tax rates may serve to deter some people from offering themselves for employment (see POVERTY TRAP). See LABOUR MARKET, DISGUISED (CONCEALED) UNEMPLOYMENT.

actual gross national product (GNP) the level of real output currently being produced by an economy. Actual GNP may or may not be equal to a country’s POTENTIAL GROSS NATIONAL PRODUCT. The level of actual GNP is determined by the interaction of AGGREGATE DEMAND and potential GNP. If aggregate demand falls short of potential GNP at any point in time, then actual GNP will be equal to aggregate demand, leaving a DEFLATIONARY GAP (output gap) between actual and potential GNP. However, at high levels of aggregate demand (in excess of potential GNP), potential GNP sets a ceiling on actual output, and any excess of aggregate demand over potential GNP shows up as an INFLATIONARY GAP.

Over time, the rate of growth of actual GNP will depend upon the rate of growth of aggregate demand, on the one hand, and the growth of potential GNP, on the other.

actuary a statistician who calculates insurance risks and premiums. See RISK AND UNCERTAINTY, INSURANCE COMPANY.

adaptive expectations (of inflation) the idea that EXPECTATIONS of the future rate of INFLATION are based on the inflationary experience of the recent past. As a result, once under way, inflation feeds upon itself with, for example, trade unions demanding an increase in wages in the current pay round, which takes into account the expected future rate of inflation which, in turn, leads to further price rises. See EXPECTATIONS-ADJUSTED/AUGMENTED PHILLIPS CURVE, INFLATIONARY SPIRAL, RATIONAL EXPECTATIONS, HYPOTHESIS, ANTICIPATED INFLATION, TRANSMISSION MECHANISM.

‘adjustable peg’ exchange-rate system a form of FIXED EXCHANGE-RATE SYSTEM originally operated by the INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND, in which the EXCHANGE RATES between currencies are fixed (pegged) at particular values (for example, £1 = $3), but which can be changed to new fixed values should circumstances require it. For example, £1 = $2, the re-pegging of the pound at a lower value in terms of the dollar (DEVALUATION); or £1 = $4, the re-pegging of the pound at a higher value in terms of the dollar (REVALUATION).

adjustment mechanism a means of correcting balance of payments disequilibriums between countries. There are three main ways of removing payments deficits or surpluses:

(a) external price adjustments;

(b) internal price and income adjustments;

(c) trade and foreign-exchange restrictions. See BALANCE-OF-PAYMENTS EQUILIBRIUM for further elaboration.

While conventional balance of payments theory emphasizes the role of monetary adjustments (e.g. EXCHANGE RATE devaluations/depreciations) in the removal of payments imbalances, a crucial requirement in this process is for there to be a real adjustment in terms of industrial efficiency and competitiveness. An example will reinforce this point. Let us assume that, because UK goods are more expensive, the UK imports more manufactured goods from Japan than it exports manufactures to Japan. Since each country has its own separate domestic currency, this deficit manifests itself as a monetary phenomenon – the UK runs a balance of payments deficit with Japan, and vice-versa. Superficially, this situation can be remedied by, for example, an external price adjustment: currency devaluation/depreciation of the pound and currency revaluation/appreciation of the yen.

But price differences in the domestic prices of manufactured goods themselves reflect differences between countries in terms of their real economic strengths and weaknesses, that is, causality can be presumed to run from the real aggregates to the monetary aggregates and not the other way round: a country has a strong, appreciating currency because it has an efficient and innovative real economy; a weak currency reflects a weak economy. Simply devaluing the currency does not mean that there will be an improvement in real efficiency and competitiveness overnight. Focusing attention on the monetary aggregates tends to mask this fundamental truth. Thus, if the UK and Japan were to establish an economic union in which, as provided for by the European Union’s Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) arrangements, their individual domestic currencies would be replaced by a single currency, then, in conventional balance of payments terms, the UK’s deficit would disappear.

Or does it? It does so in monetary terms but not in real terms, that is, the disequilibrium manifests itself not in terms of cross-border (external) foreign currency flows but as an internal problem of regional imbalance. The ‘leopard has changed its spots’ – a balance of payments problem has become a regional problem, with the UK region of the customs union experiencing lower industrial activity rates, lower levels of real income and higher rates of unemployment compared with the French region. To redress this imbalance in real terms requires an improvement in the competitiveness of the UK region’s existing industries and the establishment of new industries by inward investment. For example, within the UK itself the decline of iron and steel production in Wales has been partly offset by the establishment of consumer appliance and electronics industries by American and Japanese multinational companies. See EURO, REGIONAL POLICY.

adjustment speed the rate at which MARKETS adjust to changing economic circumstances. Adjustment speeds will tend to vary between different types of market. For example, in the case of the FOREIGN EXCHANGE MARKET, the exchange rate of a currency will tend to adjust rapidly to EXCESS SUPPLY or EXCESS DEMAND for it. A similar rapid response tends to characterize COMMODITY MARKETS and MONEY MARKETS, with commodity prices and INTEREST RATES changing quickly as supply or demand conditions warrant. Product markets (see PRICE SYSTEM) tend to adjust more slowly because the prices of products are usually fixed administratively and are generally changed infrequently in response to major supply or demand changes. Finally, some commodity markets, in particular the LABOUR MARKET, tend to adjust more slowly still because wages tend to be fixed through longer-term collective bargaining arrangements. See WAGE STICKINESS.

administered price 1 a price for a PRODUCT that is set by an individual producer or group of producers. In PERFECT COMPETITION, characterized by many very small producers, the price charged is determined by the interaction of market demand and market supply, and the individual producer has no control over this price. By contrast, in an OLIGOPOLY and a MONOPOLY, large producers have considerable discretion over the prices they charge and can, for example, use some administrative formula like FULL-COST PRICING to determine the particular price charged. A number of producers may combine to administer the price of a product by operating a CARTEL or price-fixing agreement.

2 a price for a product, or CURRENCY, etc., that is set by the government or an international organization. For example, an individual government or INTERNATIONAL COMMODITY AGREEMENT may fix the prices of agricultural produce or commodities such as tin to support producers’ incomes; under an internationally managed FIXED EXCHANGE-RATE SYSTEM, member countries establish fixed values for the exchange rates of their currencies. See PRICE SUPPORT, PRICE CONTROLS.

administrator see INSOLVENCY ACT 1986.

ad valorem tax a TAX that is levied as a percentage of the price of a unit of output. See SPECIFIC TAX, VALUE-ADDED TAX.

advances see LOANS.

adverse selection the tendency for people to enter into CONTRACTS in which they can use their private information to their own advantage and to the disadvantage of the less informed party to the contract. For example, an insurance company may charge health insurance premiums based upon the average risk of people falling ill, but people with poorer than average health will be keener to take out health insurance while people with better than average health will tend not to take out such health insurance, so that the insurance company loses money because the high risk part of the population is over-represented among its clients.

Adverse selection results directly from ASYMMETRY OF INFORMATION available to the parties to a contract or TRANSACTION. Where there is hidden information that is private and unobservable to other parties to a transaction, the presence of hidden information or even the suspicion of hidden information may be sufficient to hinder parties from entering into transactions.

advertisement a written or visual presentation in the MEDIA of a BRAND of a good or service that is used both to ‘inform’ prospective buyers of the product’s attributes and to ‘persuade’ them to purchase it in preference to competing brands. Advertisements are usually featured as part of an ‘advertising campaign’ involving a series of presentations of the brand in the media over a run of weeks, months or even years that is designed to reinforce the ‘image’ of the brand, thereby expanding sales of the product and establishing BRAND LOYALTY. See ADVERTISING.

advertising a means of stimulating demand for a product and establishing strong BRAND LOYALTY. Advertising is one of the main forms of PRODUCT DIFFERENTIATION competition and is used both to inform prospective buyers of a brand’s particular attributes and to persuade them that the brand is superior to competitors’ offerings.

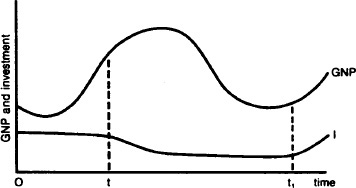

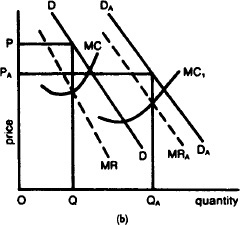

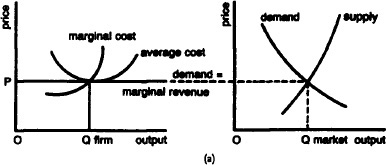

Fig. 3 Advertising. (a) The static market effects of advertising on demand (D). The profit maximizing (see PROFIT MAXIMIZATION) price-output combination (PQ) without advertising is shown by the intersection of the marginal revenue curve (MR) and the marginal cost curve (MC). By contrast, the addition of advertising costs serves to shift the marginal cost curve to MC1, so that the PQ combination (shown by the intersection of MR and MC1) now results in higher price (PA) and lower quantity supplied (QA).

(b) The initial profit-maximizing price-output combination (PQ) without advertising is shown by the intersection of the marginal revenue curve (MR) and the marginal cost curve (MC). The effect of advertising is to expand total market demand from DD to DADA with a new marginal revenue curve (MRA). This expansion of market demand enables the industry to achieve economies of scale in production, which more than offsets the additional advertising cost. Hence, the marginal cost curve in the expended market (MC1) is lower than the original marginal cost curve. The new profit maximizing price-output combination (determined by the intersection at MRA and MC1 results in a lower price (PA) than before and a larger quantity supplied (QA). See BARRIERS TO ENTRY, MONOPOLISTIC COMPETITION, OLIGOPOLY, DISTRIBUTIVE EFFICIENCY.

There are two contrasting views of advertising’s effect on MARKET PERFORMANCE. Traditional ‘static’ market theory, on the one hand, emphasizes the misallocative effects of advertising. Here advertising is depicted as being solely concerned with brand-switching between competitors within a static overall market demand and serves to increase total supply costs and the price paid by the consumer. This is depicted in Fig. 3 (a). (See PROFIT MAXIMIZATION).

The alternative view of advertising emphasizes its role as one of expanding market demand and ensuring that firms’ demand is maintained at levels that enable them to achieve economies of large-scale production (see ECONOMIES OF SCALE). Thus, advertising may be associated with a higher market output and lower prices than allowed for in the static model. This is illustrated in Fig. 3 (b).

advertising agency a business that specializes in providing marketing services for firms. Agencies usually devise, programme and manage specific advertising campaigns on behalf of clients. See ADVERTISEMENT, ADVERTISING.

Advertising Standards Authority (ASA) a body that regulates the UK ADVERTISING industry to ensure that ADVERTISEMENTS provide a fair, honest and unambiguous representation of the products they promote.

Advisory, Conciliation and Arbitration Service (ACAS) a body established in the UK in 1975 to provide counselling services with regard to INDUSTRIAL RELATIONS and employment policy matters, in particular that of MEDIATION, CONCILIATION and ARBITRATION in cases of INDUSTRIAL DISPUTE.

after-sales service the provision of back-up facilities by a supplier or his agent to a customer after he has purchased the product. After-sales service includes the replacement of faulty products or parts and the repair and maintenance of the product on a regular basis. These services are often provided free of charge for a limited period of time through formal guarantees of product quality and performance, and thereafter, for a modest fee, as a means of securing continuing customer goodwill. After-sales service is thus an important part of competitive strategy. See PRODUCT DIFFERENTIATION.

agency cost a form of failure in the contractual relationship between a PRINCIPAL (the owner of a firm or other assets) and an AGENT (the person contacted by the principal to manage the firm or other assets). This failure arises because the principal cannot fully monitor the activities of the agent. Thus there is a possibility that an agent may not act in the interests of his principal, unless the principal can design an appropriate reward structure for the agent that aligns the agent’s interests with those of the principal.

Agency relations can exist between firms, for example, licensing and franchising arrangements between the owner of a branded product (the principal) and licensees who wish to make and sell that product (agents). However, agency relations can also exist within firms, particularly in the relationship between the shareholders who own a public JOINT-STOCK COMPANY (the principals) and salaried professional managers who run the company (the agents). Agency costs can arise from slack effort by employees and the cost of monitoring and supervision designed to deter slack effort. See PRINCIPAL-AGENT THEORY, CONTRACT, TRANSACTION, DIVORCE OF OWNERSHIP FROM CONTROL, MANAGERIAL THEORIES OF THE FIRM, TEAM PRODUCTION.

agent a person or company employed by another person or company (called the principal) for the purpose of arranging CONTRACTS between the principal and third parties. An agent thus acts as an intermediary in bringing together buyers and sellers of a good or service, receiving a flat or sliding-scale commission, brokerage or fee related to the nature and comprehensiveness of the work undertaken and/or value of the transaction involved. Agents and agencies are encountered in one way or another in most economic activities and play an important role in the smooth functioning of the market mechanism. See PRINCIPAL-AGENT THEORY for discussion of ownership and control issues as they affect the running of companies. See ESTATE AGENT, INSURANCE BROKER, STOCKBROKER, DIVORCE OF OWNERSHIP FROM CONTROL.

aggregate concentration see CONCENTRATION MEASURES.

aggregate demand or aggregate expenditure the total amount of expenditure (in nominal terms) on domestic goods and services. In the CIRCULAR FLOW OF NATIONAL INCOME MODEL aggregate demand is made up of CONSUMPTION EXPENDITURE (C), INVESTMENT EXPENDITURE (I), GOVERNMENT EXPENDITURE (G) and net EXPORTS (exports less imports) (E):

aggregate demand = C + I + G + E

Some of the components of aggregate demand are relatively stable and change only slowly over time (e.g. consumption expenditure); others are much more volatile and change rapidly, causing fluctuations in the level of economic activity (e.g. investment expenditure).

In 2003, consumption expenditure accounted for 52%, investment expenditure accounted for 13%, government expenditure accounted for 15% and exports accounted for 20% of gross final expenditure (GFE) on domestically produced output. (GFE minus imports = GROSS DOMESTIC PRODUCT). See Fig. 133 (a) NATIONAL INCOME ACCOUNTS.

Aggregate demand interacts with AGGREGATE SUPPLY to determine the EQUILIBRIUM LEVEL OF NATIONAL INCOME. Governments seek to regulate the level of aggregate demand in order to maintain FULL EMPLOYMENT, avoid INFLATION, promote ECONOMIC GROWTH and secure BALANCE-OF-PAYMENTS EQUILIBRIUM through the use of FISCAL POLICY and MONETARY POLICY. See AGGREGATE DEMAND SCHEDULE, ACTUAL GROSS NATIONAL PRODUCTS DEFLATIONARY GAP, INFLATIONARY GAP, BUSINESS CYCLE, STABILIZATION POLICY, POTENTIAL GROSS NATIONAL PRODUCT.

aggregate demand/aggregate supply approach to national income determination see EQUILIBRIUM LEVEL OF NATIONAL INCOME.

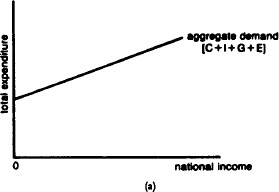

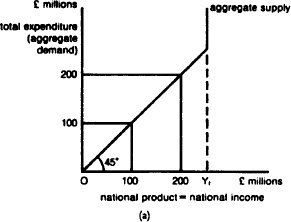

aggregate demand schedule a schedule depicting the total amount of spending on domestic goods and services at various levels of NATIONAL INCOME. It is constructed by adding together the CONSUMPTION, INVESTMENT, GOVERNMENT EXPENDITURE and EXPORTS schedules, as indicated in Fig. 4 (a).

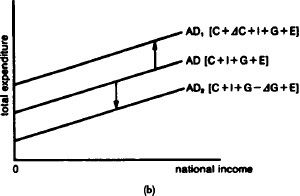

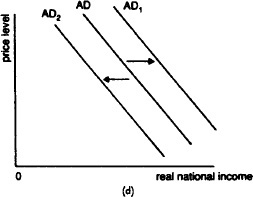

A given aggregate demand schedule is drawn up on the usual CETERIS PARIBUS conditions. It will shift upwards or downwards if some determining factor changes. See Fig. 4 (b).

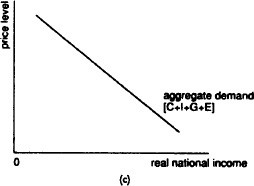

Alternatively, the aggregate demand schedule can be expressed in terms of various levels of real national income demanded at each PRICE LEVEL as shown in Fig. 4 (c). This alternative schedule is also drawn on the assumption that other influences on spending plans are constant. It will shift rightwards or leftwards if some determining factors change. See Fig. 4 (d). This version of the aggregate demand schedule parallels at the macro level the demand schedule and DEMAND CURVE for an individual product, although in this case the schedule represents demand for all goods and services and deals with the general price level rather than with a particular price.

Fig. 4 Aggregate demand schedule. (a) The graph shows how AGGREGATE DEMAND varies with the level of NATIONAL INCOME.

b) Shifts in the schedule because of determining factor changes. For example, if there is an increase in the PROPENSITY TO CONSUME, the consumption schedule will shift upwards, serving to shift the aggregate demand schedule upwards from AD to AD1; a reduction in government spending will shift the schedule downwards from AD to AD2.

(c)The graph plots the quantity of real national income demanded against the price level.

(d) Shifts in the schedule because of determining factor changes. For example, if there is an increase in the propensity to consume, the aggregate demand schedule will shift rightwards from AD to AD1; a reduction in government spending will shift the schedule leftwards from AD to AD2.

aggregated rebate a trade practice whereby DISCOUNTS on purchases are related not to customers’ individual orders but to their total purchases over a period of time. Aggregated rebate is used to foster buyer loyalty to the supplier, but it can produce anti-competitive effects because it encourages buyers to place the whole of their orders with one supplier, to the exclusion of competing suppliers. Under the Competition Act 1980, aggregated rebates can be investigated by the Office of Fair Trading and (if necessary) the COMPETITION COMMISSION and prohibited if found to unduly restrict competition.

aggregate expenditure see AGGREGATE DEMAND.

aggregate supply the total amount of domestic goods and services supplied by businesses and government, including both consumer products and capital goods. Aggregate supply interacts with AGGREGATE DEMAND to determine the EQUILIBRIUM LEVEL OF NATIONAL INCOME (see AGGREGATE SUPPLY SCHEDULE).

In the short term, aggregate supply will tend to vary with the level of demand for goods and services, although the two need not correspond exactly. For example, businesses could supply more products than are demanded in the short term, the difference showing up as a build-up of unsold STOCKS (unintended INVENTORY INVESTMENT). On the other hand, businesses could supply fewer products than are demanded in the short term, the difference being met by running down stocks. However, discrepancies between aggregate supply and aggregate demand cannot be very large or persist for long, and generally businesses will offer to supply output only if they expect spending to be sufficient to sell all that output.

Over the long term, aggregate supply can increase as a result of increases in the LABOUR FORCE, increases in CAPITAL STOCK and improvements in labour PRODUCTIVITY. See ACTUAL GROSS NATIONAL PRODUCT, POTENTIAL GROSS NATIONAL PRODUCT, ECONOMIC GROWTH.

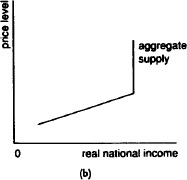

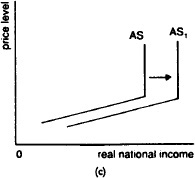

aggregate supply schedule a schedule depicting the total amount of domestic goods and services supplied by businesses and government at various levels of total expenditure. The AGGREGATE SUPPLY schedule is generally drawn as a 45° line because business will offer any particular level of national output only if they expect total spending (AGGREGATE DEMAND) to be just sufficient to sell all of that output. Thus, in Fig. 5 (a), £100 million of expenditure calls forth £100 million of aggregate supply, £200 million of expenditure calls forth £200 million of aggregate supply, and so on. This process cannot continue indefinitely, however, for once an economy’s resources are fully employed in supplying products then additional expenditure cannot be met from additional domestic resources because the potential output ceiling of the economy has been reached. Consequently, beyond the full-employment level of national product, Yf, the aggregate supply schedule becomes vertical. See POTENTIAL GROSS NATIONAL PRODUCT, ACTUAL GROSS NATIONAL PRODUCT.

Alternatively, the aggregate supply schedule can be expressed in terms of various levels of real national income supplied at each PRICE LEVEL as shown in Fig. 5 (b). This version of the aggregate supply schedule parallels at the macro level the supply schedule and SUPPLY CURVE for an individual product, though in this case the schedule represents the supply of all goods and services and deals with the general price level rather than a particular product price. Fig. 5 (c) shows a shift of the aggregate supply curve to the right as a result of, for example, increases in the labour force or capital stock and technological advances.

Aggregate supply interacts with aggregate demand to determine the EQUILIBRIUM LEVEL OF NATIONAL INCOME.

Fig. 5 Aggregate supply schedule. See entry.

AGM see ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING.

agricultural policy a policy concerned both with protecting the economic interests of the agricultural community by subsidizing farm prices and incomes, and with promoting greater efficiency by encouraging farm consolidation and mechanization.

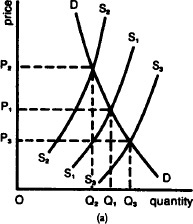

Fig. 6 Agricultural policy. (a) The short-term shifts in supply (S) and their effects on price (P) and quantity (Q).

(b) Long-term shifts caused by the influence of productivity improvement on supply.

The rationale for supporting agriculture partly reflects the ‘special case’ nature of the industry itself: agriculture, unlike manufacturing industry, is especially vulnerable to events outside its immediate control. Supply tends to fluctuate erratically from year to year, depending upon such vagaries as the weather and the incidence of pestilence and disease, S1, S2 and S3 in Fig. 6 (a), causing wide changes in farm prices and farm incomes. Over the long term, while the demand for many basic foodstuffs and animal produce has grown only slowly, from DD to D1D1 in Fig. 6 (b), significant PRODUCTIVITY improvements associated with farm mechanization, chemical fertilizers and pesticides, etc., have tended to increase supply at a faster rate than demand, from SS to S1S1 in Fig. 6 (b), causing farm prices and incomes to fall (see MARKET FAILURE).

Farming can thus be very much a hit-and-miss affair, and governments concerned with the impact of changes in food supplies and prices (on, for example, the level of farm incomes, the balance of payments and inflation rates) may well feel some imperative to regulate the situation. But there are also social and political factors at work; for example, the desire to preserve rural communities and the fact that, even in some advanced industrial countries (for example, the European Union), the agricultural sector often commands a political vote out of all proportion to its economic weight. See ENGEL’S LAW, COBWEB THEOREM, PRICE SUPPORT, INCOME SUPPORT, COMMON AGRICULTURAL POLICY, FOOD AND AGRICULTURAL ORGANIZATION.

aid see ECONOMIC AID.

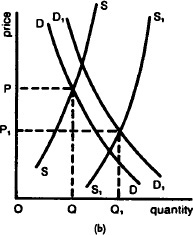

allocative efficiency an aspect of MARKET PERFORMANCE that denotes the optimum allocation of scarce resources between end users in order to produce that combination of goods and services that best accords with the pattern of consumer demand. This is achieved when all market prices and profit levels are consistent with the real resource costs of supplying products. Specifically, consumer welfare is optimized when for each product the price is equal to the lowest real resource cost of supplying that product, including a NORMAL PROFIT reward to suppliers. Fig. 7 (a) depicts a normal profit equilibrium under conditions of PERFECT COMPETITION with price being determined by the intersection of the market supply and demand curves and with MARKET ENTRY/MARKET EXIT serving to ensure that price (P) is equal to minimum supply cost in the long run (AC).

Fig. 7 Allocative efficiency. (a) A normal profit equilibrium under conditions of perfect competition. (b) The profit maximizing price-output combination for a monopolist.

By contrast, where some markets are characterized by monopoly elements, then in these markets output will tend to be restricted so that fewer resources are devoted to producing these products than the pattern of consumer demand warrants. In these markets, prices and profit levels are not consistent with the real resource costs of supplying the products. Specifically, in MONOPOLY markets the consumer is exploited by having to pay a price for a product that exceeds the real resource cost of supplying it, this excess showing up as an ABOVE-NORMAL PROFIT for the monopolist.

Fig. 7 (b) depicts the profit maximizing price-output combination for a monopolist, determined by equating marginal cost and marginal revenue. This involves a smaller output and a higher price than would be the case under perfect competition, with BARRIERS TO ENTRY serving to ensure that the output restriction and excess prices persist over the long run. See PARETO OPTIMALITY, MARKET FAILURE.

Alternative Investment Market see UNLISTED-SECURITIES MARKET.

amalgamation see MERGER.

Amsterdam Treaty, 1997 a EUROPEAN UNION (EU) statute that extended various provisions of the MAASTRICHT TREATY in the areas of social policy (particularly discriminations against persons and the integration of the SOCIAL CHAPTER), internal procedures for the administration of EU institutions and the EU’s Common Foreign and Security Policy (including defence).

Andean Pact a regional alliance originally formed in 1969 with the general objective of establishing a COMMON MARKET. The current members of the Andean Pact are Peru, Chile, Ecuador, Columbia and Bolivia. By the mid 1980s, however, it had all but collapsed because of various economic and political instabilities. The Pact was relaunched in 1990 minus Chile but with a new member, Venezuela, renewing its commitment to the eventual introduction of a common market. See TRADE INTEGRATION.

annual general meeting (AGM) the yearly meeting of SHAREHOLDERS that JOINT-STOCK COMPANIES are required by law to convene, in order to allow shareholders to discuss their company’s ANNUAL REPORT AND ACCOUNTS, elect members of the BOARD OF DIRECTORS and agree the DIVIDEND payouts suggested by directors. In practice, annual general meetings are usually poorly attended by shareholders and only rarely do directors fail to be re-elected on the strength of PROXY votes cast in favour of the directors. See CORPORATE GOVERNANCE.

annual report and accounts a yearly report by the directors of a JOINT-STOCK COMPANY to the SHAREHOLDERS. It includes a copy of the company’s BALANCE SHEET and a summary PROFIT-AND-LOSS ACCOUNT, along with other information that directors are required by law to disclose to shareholders. A copy of the annual report and accounts is sent to every shareholder prior to the company’s ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING.

annuity a series of equal payments at fixed intervals from an original lump sum INVESTMENT. Where an annuity has a fixed time span, it is termed an annuity certain, and the periodic receipts comprise both a phased repayment of principal (the original lump sum payment) and interest, such that at the end of the fixed term there is a zero balance on the account. An annuity in perpetuity does not have a fixed time span but continues indefinitely and receipts can therefore come only from interest earned. Annuities can be obtained from pension funds or life insurance schemes.

anticipated inflation the future INFLATION rate in a country that is generally expected by business people, trade union officials and consumers. People’s anticipations about the inflation rate will influence their price-setting, wage bargaining and spending/saving decisions. As part of its policy to reduce inflation, governments seek to influence anticipations by ‘talking down’ prospects of inflation, publishing norm percentages for prices and incomes, etc. Compare UNANTICIPATED INFLATION. See EXPECTATIONS, EXPECTATIONS-ADJUSTED/AUGMENTED PHILLIPS CURVE.

anti-competitive agreement a form of COLLUSION between suppliers aimed at restricting or removing competition between them. For the most part, such agreements concentrate on fixing common selling prices and discounts but may also contain provisions relating to market-sharing, production quotas and coordinated capacity adjustments. The main objection to such agreements is that they raise prices above competitive levels, impose unfair terms and conditions on buyers and serve to protect inefficient suppliers from the rigours of competition. In the UK, anti-competitive agreements are prohibited by the COMPETITION ACT 1998. See also RESTRICTIVE PRACTICES COURT.

anti-competitive practice a commercial practice operated by a firm that has the effect of restricting, distorting or eliminating competition (especially if operated by a dominant firm) to the detriment of other suppliers and consumers. Examples of restrictive practices include EXCLUSIVE DEALING, REFUSAL TO SUPPLY, FULL LINE FORCING, TIE-IN SALES, AGGREGATED REBATES, RESALE PRICE MAINTENANCE and LOSS LEADING.

Under the COMPETITION ACT 1980, exclusive dealing, full line forcing, tie-in sales and aggregated rebates can be investigated by the OFFICE OF FAIR TRADING and (if necessary) the COMPETITION COMMISSION and prohibited if found to unduly restrict competition. The RESALE PRICES ACTS 1964, 1976 make the practice of resale price maintenance illegal unless it is, very exceptionally, exempted by the Office of Fair Trading. See also PRICE SQUEEZE.

anti-dumping duty see COUNTERVAILING DUTY.

antimonopoly policy see COMPETITION POLICY.

antitrust policy see COMPETITION POLICY.

APEC see ASIAN PACIFIC ECONOMIC COOPERATION.

application money the amount payable per share on application for a new SHARE ISSUE.

applied economics the application of economic analysis to real world economic situations. Applied economics seeks to employ the predictions emanating from ECONOMIC THEORY in offering advice on the formulation of ECONOMIC POLICY. See ECONOMIC MODELS, HYPOTHESIS, HYPOTHESIS TESTING.

appreciation 1 an increase in the value of a CURRENCY against other currencies under a FLOATING EXCHANGE-RATE SYSTEM. An appreciation of a currency’s value makes IMPORTS (in the local currency) cheaper and EXPORTS (in the local currency) more expensive, thereby encouraging additional imports and curbing exports, so assisting in the removal of a BALANCE OF PAYMENTS surplus and the excessive accumulation of INTERNATIONAL RESERVES.

How successful an appreciation is in removing a payments surplus depends on the reactions of export and import volumes to the change in relative prices; that is, the PRICE ELASTICITY OF DEMAND for exports and imports. If these values are low, i.e. demand is inelastic, trade volume will not change very much and the appreciation may in fact make the surplus larger. On the other hand, if export and import demand is elastic then the change in trade volumes will operate to remove the surplus, BALANCE-OF-PAYMENTS EQUILIBRIUM will be restored if the sum of export and import elasticities is greater than unity (the MARSHALL-LERNER CONDITION). See REVALUATION for further points. Compare DEPRECIATION 1. See INTERNAL-EXTERNAL BALANCE MODEL. 2 an increase in the price of an ASSET and also called capital appreciation. Assets held for long periods, such as factory buildings, offices or houses, are most likely to appreciate in value because of the effects of INFLATION and increasing site values, though the value of short-term assets like STOCKS can also appreciate. Where assets appreciate, then their REPLACEMENT COST will exceed their HISTORIC COST, and such assets may need to be revalued periodically to keep their book values in line with their market values. See DEPRECIATION 2, INFLATION ACCOUNTING.

apprentice see TRAINING.

APR the ‘annualized percentage rate of INTEREST’ charged on a LOAN. The APR rate will depend on the total ‘charge for credit’ applied by the lender and will be influenced by such factors as the general level of INTEREST RATES, and the nature and duration of the loan.

Where lenders relate total interest charges on INSTALMENT CREDIT loans to the original amount borrowed, this can give a misleading impression of the interest rate being charged, for as borrowers make monthly or weekly repayments on the loan, they are reducing the amount borrowed, and interest charges should be related to the lower average amount owed. For example, if someone borrows £1,000 for one year with a total credit charge of £200, the ‘simple interest’ charge on the original loan is 20%. However, if the loan terms provide for monthly repayments of £100, then at the end of the first month the borrower would have repaid a proportion of the original £1,000 borrowed and by the end of the second month would have repaid a further proportion of the original loan, etc. In effect, therefore, the borrower does not borrow £1,000 for one whole year but much less than this over the year on average, as he or she repays part of the outstanding loan. If the total credit charge of £200 were related to this much smaller average amount borrowed to show the ‘annualized percentage rate’, then this credit charge would be nearer 40% than the 20% quoted.

To make clear to the borrower the actual charge for credit and the ‘true’ rate of interest, the CONSUMER CREDIT ACT 1974 requires lenders to publish both rates to potential borrowers.

a priori adj. known to be true, independently of the subject under debate. Economists frequently develop their theoretical models by reasoning, deductively, from certain prior assumptions to general predictions.

For example, operating on the assumption that consumers behave rationally in seeking to maximize their utility from a limited income, economists’ reasoning leads them to the prediction that consumers will tend to buy more of those products whose relative price has fallen. See ECONOMIC MAN, CONSUMER EQUILIBRIUM

arbitrage the buying or selling of PRODUCTS, FINANCIAL SECURITIES or FOREIGN CURRENCIES between two or more MARKETS in order to take profitable advantage of any differences in the prices quoted in these markets. By simultaneously buying in a low-price market and selling in the high-price market a dealer can make a profit from any disparity in prices between them, though in the process of buying and selling the dealer will add to DEMAND in the low-price market and add to SUPPLY in the high-price market, so narrowing or eliminating the price disparity. See SPOT MARKET, FUTURES MARKET, COVERED INTEREST ARBITRAGE.

arbitration a procedure for settling disputes, most notably INDUSTRIAL DISPUTES, in which a neutral third party or arbitrator, after hearing presentations from all sides in dispute, issues an award binding upon each side. Arbitration is mostly used only as a last resort when normal negotiating proceedings have failed to bring about an agreed settlement. In the UK, the ADVISORY CONCILIATION AND ARBITRATION SERVICE (ACAS) acts in this capacity. See MEDIATION, COLLECTIVE BARGAINING, INDUSTRIAL RELATIONS.

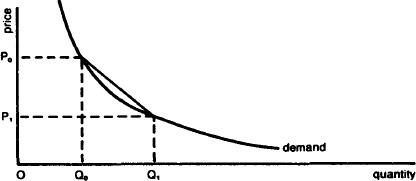

arc elasticity a rough measure of the responsiveness of DEMAND or SUPPLY to changes in PRICE, INCOME, etc. In the case of PRICE ELASTICITY OF DEMAND, it is the ratio of the percentage change in quantity demanded (Q) to the percentage change in price (P) over a price range such as P0 to P1 in Fig. 8. Arc elasticity of demand is expressed notationally as:

![]()

where P0 = original price, Q0 = original quantity, P1 = new price, Q1 = new quantity. Because arc elasticity measures the elasticity of demand (e) over a price range or arc of the demand curve, it is only an approximation of demand elasticity at a particular price (POINT ELASTICITY). However, the arc elasticity formula gives a reasonable degree of accuracy in approximating point elasticity when price and/or quantity changes are small. See also ELASTICITY OF DEMAND.

articles of association the legal constitution of a JOINT-STOCK COMPANY that governs the internal relationship between the company and its members or SHAREHOLDERS. The articles govern the rights and duties of the membership and aspects of administration of the company. They will contain, for instance, the powers of the directors, the conduct of meetings, the dividend and voting rights assigned to separate classes of shareholders, and other miscellaneous rules and regulations. See MEMORANDUM OF ASSOCIATION.

ASA see ADVERTISING STANDARDS AUTHORITY.

ASEAN see ASSOCIATION OF SOUTHEAST ASIAN NATIONS.

Asian Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) a regional alliance formed in 1990 with the general objective of establishing a FREE TRADE AREA, specifically creating a free trade zone for industrialized country members by 2010 and for developing country members by 2020. There are currently 17 members of APEC: USA, Canada, Japan, China/Hong Kong, Mexico, Chile, Australia, New Zealand, Papua New Guinea, South Korea, Taiwan, Thailand, Philippines, Brunei, Malaysia, Singapore and Indonesia. The USA, Canada and Mexico are also members of the NORTH AMERICAN FREE TRADE AGREEMENT (NAFTA), and Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore and Thailand are also members of the ASSOCIATION OF SOUTHEAST ASIAN NATIONS (ASEAN). See TRADE INTEGRATION.

ask price see BID PRICE.

Fig. 8 Arc elasticity. See entry.

asset an item or property owned by an individual or a business that has a money value. Assets are of three main types: (a) physical assets, such as plant and equipment, land, consumer durables (cars, washing machines, etc);

(b) financial assets, such as currency, bank deposits, stocks and shares;

(c) intangible assets, such as BRAND NAMES, KNOW-HOW and GOODWILL. See INVESTMENT, LIQUIDITY, BALANCE SHEET, LIABILITY.

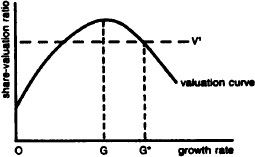

asset-growth maximization a company objective in the THEORY OF THE FIRM that is used as an alternative to the traditional assumption of PROFIT MAXIMIZATION. Salaried managers of large JOINT-STOCK COMPANIES are assumed to seek to maximize the rate of growth of net assets as a means of increasing their salaries, power, etc., subject to maintaining a minimum share value, so as to avoid the company being taken over with the possible loss of jobs. In Fig. 9, the rate of growth of assets is shown on the horizontal axis, and the ratio of the market value of company shares to the book value of company net assets (the share-valuation ratio) on the vertical axis. The valuation curve rises at first, as increasing asset growth increases share value but beyond growth rate (G) excessive retention of profits to finance growth will reduce dividend payments to shareholders and depress share values. Managers will tend to choose the fastest growth rate (G*), which does not depress the share valuation below the level (V1) at which the company risks being taken over. See also MANAGERIAL THEORIES OF THE FIRM, FIRM OBJECTIVES, DIVORCE OF OWNERSHIP FROM CONTROL, PRINCIPAL-AGENT THEORY.

asset specificity the extent to which a TRANSACTION or CONTRACT needs to be supported by transaction-specific assets. Where a contract involves the need to create transaction-specific assets, this creates a fundamental transformation in the nature of the relationship between the parties to the transaction. Before investing in specific assets, the investing partner is likely to have many alternative trading partners, which allows for bidding competition. However, after the investment creates transaction-specific assets these become SUNK COSTS with no alternative use and the parties to the transaction then have no alternative trading partners. The terms of the transaction are then determined by bilateral bargaining between the parties to the transaction.

Bargaining between the parties can lead to opportunistic behaviour where one party in a contractual relationship seeks to exploit the other’s vulnerability. For example, a seller might attempt to exploit a buyer who is dependent on the seller by claiming that the production costs have risen and pressing for an upward adjustment of the negotiated price. Such opportunistic behaviour seeks to exploit or ‘hold up’ one party to the transaction to benefit the other party

Fig. 9 Asset-growth maximization. The variation of share valuation ratio against the company growth rate.

For transactions with high asset specificity, the costs of MARKET transactions are high and such transactions are likely to be ‘internalized’ and conducted within organizations, for example a VERTICALLY INTEGRATED firm. See INTERNALIZATION.

asset-stripper a predator firm that takes control of another firm (see TAKEOVER) with a view to selling off that firm’s ASSETS, wholly or in part, for financial gain rather than continuing the firm as an ongoing business.

The classical recipe for asset-stripping arises when the realizable market value of the firm’s assets are much greater than what it would cost the predator to buy the firm; i.e. where there is a marked discrepancy between the asset-backing per share of the target firm and the price per share required to take the firm over. This discrepancy usually results from a combination of two factors:

(a) gross under-valuation of the firm’s assets in the BALANCE SHEET;

(b) mismanagement or bad luck, resulting in low profits or losses, both of which serve to depress the firm’s share price.

asset-value theory (of exchange rate determination) an explanation of the volatility of EXCHANGE-RATE movements under a FLOATING EXCHANGE-RATE SYSTEM. Whereas the PURCHASING-POWER PARITY THEORY suggests that SPECULATION is consistent with the achievement of BALANCE-OF-PAYMENTS EQUILIBRIUM, the asset-value theory emphasizes that, in all probability, it will not be. In this theory, the exchange rate is an asset price, the relative price at which the stock of money, bills and bonds and other financial assets of a country will be willingly held by foreign and domestic asset holders. An actual alteration in the exchange rate or a change in expectations about future rates can cause asset holders to alter their portfolios. The resultant change in demand for holdings of foreign currency relative to domestic currency assets can at times produce sharp fluctuations in exchange rates. In particular, uncertainty about future market rates and the unwillingness of banks and other large financial participants in the foreign-exchange markets to take substantial positions in certain currencies, especially SOFT CURRENCIES, may diminish funds for stabilizing speculation that would in turn diminish or avoid erratic exchange-rate movements.

If this should prove the case, then financial asset-switching is likely to reinforce and magnify exchange-rate movements initiated by current account transactions (i.e. changes in imports and exports), and in consequence may produce exchange rates that are inconsistent with effective overall balance-of-payments equilibrium in the longer run.

assisted area an area of a country designated as qualifying for financial and other assistance under a country’s REGIONAL POLICY in order to promote industrial regeneration. Assisted areas typically suffer from severe unemployment problems resulting from the decline of local firms and industries and are characterized by INCOME PER HEAD (GDP per capita) levels that are substantially below the national average.

In the UK, the main assisted areas are ‘Tier 1’ areas (formerly DEVELOPMENT AREAS) and ‘Tier 2’ areas (formerly INTERMEDIATE AREAS). These arrangements came into force in 2000 as part of a European Union (EU) programme aimed at establishing a comparable regional aid system across all the then 15 EU member states. Under EU policy, the main criteria for designating an assisted area is a GDP per capita that is below 75% of the EU average.

In the case of the UK, the areas proposed by the government, based on electoral voting ‘wards’, are still under review by the European Commission. Proposed Tier 1 areas are Cornwall and the Scilly Isles, Merseyside, South Yorkshire, West Wales and the Valleys, together with the whole of Northern Ireland. Proposed Tier 2 areas, totalling some 1550 smaller localities, are 79 from the east of England region; 133 from the East Midland region; 44 from the London region; 228 from the Northeast region; 144 from the Northwest region; 440 from Scotland; 129 from the Southeast region; 20 from the Southwest region; 51 from Wales; 197 from the West Midlands region and 91 from the Yorkshire and Humber region. Regarding Tier 2 submissions, the European Commission’s preferred policy is to support ‘clusters’ of adjacent localities, providing sufficient ‘critical mass’ for industrial development rather than isolated localities.

In addition, a ‘Tier 3’ of assisted areas has been designated that covers areas of ‘special need’ (for example, coalfields and rural development areas).

The application of the new Tier structures is subject to an overall population ceiling requirement; specifically, for any country the number of persons residing in the assisted areas should not exceed more than 28.7% of the total population of the country. See REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT AGENCY.

associated company a JOINT-STOCK COMPANY in which another company or group has a significant, but not controlling, shareholding (specifically 20% or more of the voting shares but not more than 50%). In such a situation the investing company can exert influence on the commercial and financial policy decisions of the associated company, though in principle the associated company remains independent under its own management, producing its own annual accounts, and is not a subsidiary of the HOLDING COMPANY.

Association of British Insurers see INSURANCE COMPANY.

Association of Futures Brokers and Dealers (AFBD) see SELF-REGULATORY ORGANIZATION.

Association of Investment Trust Companies see INVESTMENT TRUST COMPANY.

Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) a regional alliance formed in 1967 with the general objective of creating a FREE TRADE AREA. The current member countries of ASEAN are Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore and Thailand. However, only limited progress has been made to date towards the reduction of internal tariffs and quotas. See ASIAN PACIFIC ECONOMIC COOPERATION, TRADE INTEGRATION.

assumptions see ECONOMIC MODEL.

assurance see INSURANCE.

asymmetry of information a situation where the parties to a CONTRACT or TRANSACTION have information available but this information is unevenly distributed between the parties. This information could include the identity of alternative suppliers or customers or product quality or performance.

Asymmetry of information is likely to lead to ADVERSE SELECTION or to MORAL HAZARD in transactions. Asymmetric information also applies to the principal-agent relationship (see AGENCY COST) where the principal cannot observe the agent’s level of effort. See PRINCIPAL-AGENT THEORY.

ATM see AUTOMATIC TELLER MACHINE.

atomistic competition see PERFECT COMPETITION.

attributes model see PRODUCT CHARACTERISTICS/ATTRIBUTES MODEL.

auction a means of selling goods and services to the highest bidder among a number of potential customers. Auctions can take several forms. One form is an open auction, increasing bid, competition in which the bids of all parties are observable and bidders drop out as the price increases until only the highest bidder remains. Another form is an open auction, decreasing price, auction in which the auctioneer starts off from a very high price that is then slowly decreased until one bidder agrees to buy at the last announced price. This form of auction is often called a ‘Dutch auction’. Yet another form is a sealed-bid, closed auction in which all bidders have to submit their bids in sealed envelopes at the same time. In open auctions, bidders can gain some information about the private valuations that other bidders place upon the goods to be sold, while in sealed-bid auctions the private valuations of bidders remain unobservable. The principles of auctions apply to situations where firms seek tenders to supply products.

audit the legal requirement for a JOINT-STOCK COMPANY to have its BALANCE SHEET and PROFIT-AND-LOSS ACCOUNT (the financial statements) and underlying accounting system and records examined by a qualified auditor, so as to enable an opinion to be formed as to whether such financial statements show a true and fair view and that they comply with the relevant statutes. See also ENVIRONMENTAL AUDIT, VALUE FOR MONEY AUDIT.

Austrian school a group of late 19th-century economists at the University of Vienna who established and developed a particular line of theoretical reasoning. The tradition originated with Professor Carl Menger who argued against the classical theories of value, which emphasized PRODUCTION and SUPPLY. Instead, he initiated the ‘subjectivist revolution’, reasoning that the value of a good was not derived from its cost but from the pleasure, or UTILITY, that the CONSUMER can derive from it. This type of reasoning led to the MARGINAL UTILITY theory of value whereby successive increments of a commodity yield DIMINISHING MARGINAL UTILITY.

Friedrich von Wieser developed the tradition further, being credited with introducing the economic concept of OPPORTUNITY COST. Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk helped to develop the theory of INTEREST and CAPITAL, arguing that the price paid for the use of capital is dependent upon consumers’ demand for present CONSUMPTION relative to future consumption. Ludwig von Mises and Friedrich von Hayek subsequently continued the tradition established by Carl Menger et al. See also CLASSICAL ECONOMICS.

authorized or registered or nominal share capital the maximum amount of SHARE CAPITAL that a JOINT-STOCK COMPANY can issue at any time. This amount is disclosed in the BALANCE SHEET and may be altered by SHAREHOLDERS at the company ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING. See also ISSUED SHARE CAPITAL.

automatic (built-in) stabilizers elements in FISCAL POLICY that serve to automatically reduce the impact of fluctuations in economic activity. A fall in NATIONAL INCOME and output reduces government TAXATION receipts and increases its unemployment and social security payments. Lower taxation receipts and higher payments increase the government’s BUDGET DEFICIT and restore some of the lost income (see CIRCULAR FLOW OF NATIONAL INCOME MODEL). See FISCAL DRAG.

automatic teller machine (ATM) a cash point (‘hole in the wall’) facility in which a banker’s card can be used by a customer of a COMMERCIAL BANK or BUILDING SOCIETY to withdraw cash both inside and outside banking hours. The ‘Link’ network enables customers to use their cards in the ATMs of other banks as well as their own.

automatic vending a means of retailing products to consumers via vending machines. Automatic vending has been employed extensively in selling, for instance, food, beverages and cigarettes. The use of vending machines has also become prominent in the banking/building society sector as a means of dispensing cash.

automation the use of mechanical or electrical machines, such as robots, to undertake frequently repeated production processes to make them self-regulating, thus minimizing or eliminating the use of labour in these processes. Automation often involves high initial capital investment but, by reducing labour costs, cuts VARIABLE COST per unit. See FLEXIBLE MANUFACTURING SYSTEM, PRODUCTIVITY, TECHNOLOGICAL PROGRESSIVENESS, CAPITAL-LABOUR RATIO, MASS PRODUCTION, COMPUTER.

autonomous consumption that part of total CONSUMPTION expenditure that does not vary with changes in NATIONAL INCOME or DISPOSABLE INCOME. In the short term, consumption expenditure consists of INDUCED CONSUMPTION (consumption expenditure that varies directly with income) and autonomous consumption. Autonomous consumption represents some minimum level of consumption expenditure that is necessary to sustain a basic standard of living and which consumers would therefore need to undertake even at zero income. See CONSUMPTION SCHEDULE.

autonomous investment that part of real INVESTMENT that is independent of the level of, and changes in, NATIONAL INCOME. Autonomous investment is mainly dependent on competitive factors such as plant modernization by businesses in order to cut costs or to take advantages of a new invention. See INDUCED INVESTMENT, INVESTMENT SCHEDULE.

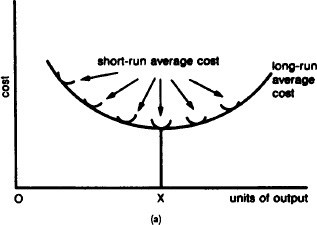

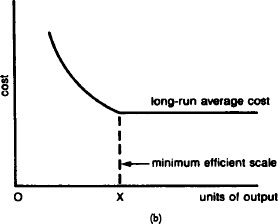

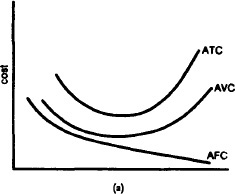

Fig. 10 Average cost (long-run). (a) The characteristic U-shape of the long-run average cost curve. (b)The characteristic L-shaped curve that in practice normally results from expansion.

average cost (long-run) the unit cost (TOTAL COST divided by number of units produced) of producing outputs for plants of different sizes. The position of the SHORT-RUN average total cost (ATC) curve depends on its existing size of plant. In the long run, a firm can alter the size of its plant. Each plant size corresponds to a different U-shaped short-run ATC curve. As the firm expands its scale of operation, it moves from one curve to another. The path along which the firm expands – the LONG-RUN ATC curve – is thus the envelope curve of all the possible short-run ATC curves. See Fig. 10 (a).

It will be noted that the long-run ATC curve is typically assumed to be a shallow U-shape, with a least-cost point indicated by output level OX. To begin with, average cost falls (reflecting ECONOMIES OF SCALE); eventually, however, the firm may experience DISECONOMIES OF SCALE and average cost begins to rise.

Empirical studies of companies’ long-run average-cost curves, however, suggest that diseconomies of scale are rarely encountered within the typical output ranges over which companies operate, so that most companies’ average cost curves are L-shaped, as in Fig. 10 (b). In cases where diseconomies of scale are encountered, the MINIMUM EFFICIENT SCALE at which a company will operate corresponds to the minimum point of the long-run average cost curve (Fig. 10 (a)). Where diseconomies of scale are not encountered within the typical output range, minimum efficient scale corresponds with the output at which economies of scale are exhausted and constant returns to scale begin (Fig. 10 (b)). Compare AVERAGE COST (SHORT-RUN).

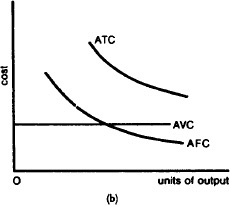

average cost (short-run) the unit cost (TOTAL COST divided by the number of units produced) of producing particular volumes of output in a plant of a given (fixed) size.

Average total cost (ATC) can be split up into average FIXED COST (AFC) and average VARIABLE COST (AVC). AFC declines continuously as output rises as a given total amount of fixed cost is ‘spread’ over a greater number of units. For example, with fixed costs of £1,000 per year and annual output of 1,000 units, fixed costs per unit would be £1, but if annual output rose to 2,000 units, the fixed cost per unit would fall to 50 pence – see AFC curve in Fig. 11 (a).

Over the whole potential output range within which a firm can produce, AVC falls at first (reflecting increasing RETURNS TO THE VARIABLE FACTOR INPUT output increases faster than costs), but then rises (reflecting DIMINISHING RETURNS to the variable inputs – costs increase faster than output), as shown by the AVC curve in Fig. 11 (a). Thus the conventional SHORT-RUN ATC curve is U-shaped.

Fig. 11 Average cost (short-run). (a) The characteristic curves of average total cost (ATC), average variable cost (AVC), and average fixed cost (AFC), over the whole output range. (b) The characteristic curves of ATC and AFC and constant line of AVC over the restricted output range.

Over the more restricted output range in which firms typically operate, however, constant returns to the variable input are more likely to be experienced, where, as more variable inputs are added to the fixed inputs employed in production, equal increments in output result. In such circumstances, AVC will remain constant over the whole output range, as in Fig. 11 (b), and as a consequence ATC will decline in parallel with AFC. Compare AVERAGE COST (LONG-RUN). See LOSS, LOSS MINIMIZATION.

average-cost pricing 1 a pricing method that sets the PRICE of a product by adding a percentage profit mark-up to AVERAGE COST or unit total cost. This method is identical in most respects to FULL-COST PRICING; indeed, the terms are often used interchangeably.

2 a pricing principle that argues for setting PRICES equal to the AVERAGE COST of production and distribution, so that prices cover both MARGINAL COSTS and FIXED OVERHEADS costs incurred through past investments. This involves the (sometimes arbitrary) apportionment of fixed (overhead) costs to individual units of output, though it does seek to recover in the price charged all the costs that would have been avoided by not producing the product. See MARGINAL-COST PRICING, TWO-PART TARIFF.

average fixed cost see AVERAGE COST (SHORT-RUN).

average physical product the average OUTPUT in the SHORT-RUN theory of supply produced by each extra unit of VARIABLE FACTOR INPUT (in conjunction with a given amount of FIXED FACTOR INPUT). This is calculated by dividing the total quantity of OUTPUT produced by the number of units of input used. In the SHORT RUN theory of supply, average physical product, together with AVERAGE REVENUE per unit of output, indicates to a firm how many factor inputs to employ in order to maximize profit. See MARGINAL PHYSICAL PRODUCT, DIMINISHING RETURNS, VARIABLE-FACTOR INPUT.

average propensity to consume (APC) the fraction of a given level of NATIONAL INCOME that is spent on consumption:

![]()

Alternatively, consumption can be expressed as a proportion of DISPOSABLE INCOME. See CONSUMPTION EXPENDITURE, PROPENSITY TO CONSUME, MARGINAL PROPENSITY TO CONSUME.

average propensity to import (APM) the fraction of a given level of NATIONAL INCOME that is spent on IMPORTS:

![]()

Alternatively, imports can be expressed as a proportion of DISPOSABLE INCOME. See also PROPENSITY TO IMPORT, MARGINAL PROPENSITY TO IMPORT.

average propensity to save (APS) the fraction of a given level of NATIONAL INCOME that is saved (see SAVING):

![]()

Alternatively, saving can be expressed as a proportion of DISPOSABLE INCOME. See also PROPENSITY TO SAVE, MARGINAL PROPENSITY TO SAVE.

average propensity to tax (APT) the fraction of a given level of NATIONAL INCOME that is appropriated by the government in TAXATION:

![]()

See also PROPENSITY TO TAX, MARGINAL PROPENSITY TO TAX, AVERAGE RATE OF TAXATION.

average rate of taxation the total TAX paid by an individual divided by the total income upon which the tax was based. For example, if an individual earned £10,000 in one year upon which that individual had to pay tax of £2,500, the average rate of taxation would be 25%. See STANDARD RATE OF TAXATION, MARGINAL RATE OF TAXATION, PROPENSITY TO TAX, PROPORTIONAL TAXATION, REGRESSIVE TAXATION, PROGRESSIVE TAXATION.

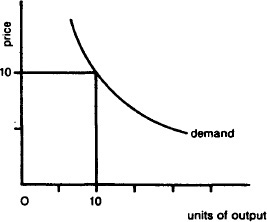

average revenue the total revenue received (price X number of units sold) divided by the number of units. Price and average revenue are in fact equal: i.e. in Fig. 12, the price £10 = average revenue (£10 × 10 ÷ 10) = £10. It follows that the DEMAND CURVE is also the average revenue curve facing the firm.

average revenue product the total REVENUE obtained from using a given quantity of VARIABLE-FACTOR INPUT to produce and sell output, divided by the number of units of input. The average revenue product of a factor is given by the factor’s AVERAGE PHYSICAL PRODUCT multiplied by the AVERAGE REVENUE or PRICE of the product. The average revenue product, together with average cost, indicates to a firm how many factor inputs to employ in order to maximize profit in the SHORT RUN. See MARGINAL REVENUE PRODUCT.

Fig. 12 Average revenue. The demand curve or average revenue curve.

average total cost (ATC) see AVERAGE COST (SHORT-RUN), AVERAGE COST (LONG-RUN).

average variable cost (AVC) see AVERAGE COST (SHORT-RUN), AVERAGE COST (LONG-RUN).