NAFTA see NORTH AMERICAN FREE TRADE AGREEMENT.

narrow money see MONEY SUPPLY.

NASDAQ the US STOCK EXCHANGE, based in New York, that specializes in the high-tech companies such as Microsoft, Dell and Amazon. The Nasdaq SHARE PRICE INDEX monitors and records the share price movements of the companies listed in the exchange. See DOW-JONES INDEX.

In 1999 Nasdaq set up an exchange in London as a direct competitor to the London Stock Exchange’s Techmark exchange.

Nash equilibrium see GAME THEORY.

National Board for Prices and Income a UK regulatory body that acted to control prices, wages, etc., under the government’s PRICES AND INCOMES POLICY from 1965 to 1970.

national debt or government debt the money owed by central government to domestic and foreign lenders. A national debt arises as a result of the government spending more than it receives in taxation and other receipts (BUDGET DEFICIT). This may arise because of, for example, a ‘one-off’ event (the financing of a war) or reflect the government’s commitment to an expansionary FISCAL POLICY.

National debt in the UK is made up of a number of financial instruments, primarily short-dated TREASURY BILLS and long-dated BONDS, together with national savings certificates. INTEREST on the national debt is paid out of current budget receipts.

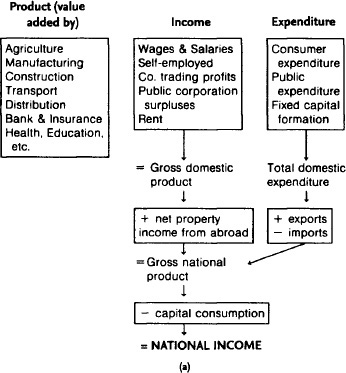

Concern is sometimes expressed at the size of the national debt. In 2003, for example, the UK’s net national debt stood at £375,200 million, compared to current GROSS DOMESTIC PRODUCT of £1,099,896 million. Provided that the bulk of the debt is held by domestic residents and institutions, however, there is no cause for alarm. In terms of the CIRCULAR FLOW OF NATIONAL INCOME, the interest paid on the national debt to domestic lenders is only a TRANSFER PAYMENT and does not represent a net reduction in the real resources of the economy or compromise the ability of the economy to provide goods and services. In 2003, 90% of the UK’s national debt was held domestically and interest payments accounted for only 5% of total GOVERNMENT EXPENDITURE.

In recent years, however, particular attention has been focused on the potentially INFLATIONARY effects of deficits financing (see PUBLIC SECTOR BORROWING REQUIREMENT) whereby deficits are financed by excessive monetary expansion. In the European Union, ‘fiscal stability’ has been written into the MAASTRICHT TREATY, with countries being under an obligation to ensure that total outstanding government debt should not exceed 60% of GDP. The UK government has gone further than this. Under the ‘sustainable-investment rule’, the government has committed itself to ensuring that total outstanding public debt should not exceed a maximum of 40% of GDP. See BUDGET (GOVERNMENT), PUBLIC SECTOR DEBT REQUIREMENT.

National Economic Development Council (NEDC) an organization that operated in the UK from 1962 to 1992 whose objective was to improve the country’s poor economic performance compared to other advanced industrial countries. NEDC was created as a form of economic-planning agency, bringing together the government and both sides of industry, management and the trade unions, with a general remit to identify obstacles to the attainment of improved efficiency and growth and to formulate appropriate means of overcoming them. At the ‘grass-roots’ level, NEDC was represented by various subcommittees (Economic Development Committees), each covering a particular industrial sector, with the main NEDC body playing a supportive and coordinating role. See also INDICATIVE PLANNING, NATIONAL PLAN.

national income or factor income the total money income received by households in return for supplying FACTOR INPUTS to business over a given period of time. National income is equal to NET NATIONAL PRODUCT and consists of the total money value of goods and services produced over the given time period (GROSS NATIONAL PRODUCT) less CAPITAL CONSUMPTION. See NATIONAL INCOME ACCOUNTS, CIRCULAR FLOW OF NATIONAL INCOME.

national income accounts the national economic statistics that show the state of the economy over a period of time (usually one year), NATIONAL INCOME is the net value of all goods and services (NATIONAL PRODUCT) produced annually in a nation: it provides a useful money measure of economic activity and, by calculating national income per head of population, serves as a useful indicator of living standards. In this latter use, it is possible to compare living standards over time or to make international comparisons of living standards.

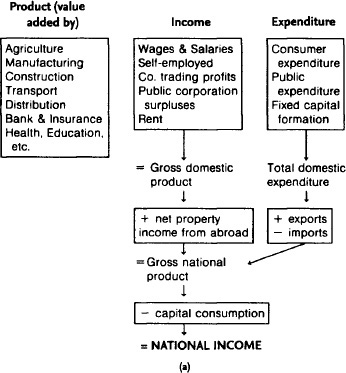

National income can be considered in three ways, as Fig. 133 (a) suggests:

(a) the domestic product/output of goods and services produced by enterprises within the country (value-added approach to GDP). This total output does not include the value of imported goods and services. To avoid overstating the value of output produced by double counting both the final output of goods and services and the output of intermediate components and services that are eventually absorbed in final output, only the VALUE ADDED at each stage of the production process is counted. The sum of all the value added by various sections of the economy (agriculture, manufacturing, etc.) is known as the GROSS DOMESTIC PRODUCT (GDP); and to arrive at the GROSS NATIONAL PRODUCT (GNP), it is necessary to add net property income from abroad (defined as net income in the form of interest, rent, profits and dividends accruing to a nation’s citizens from their ownership of assets abroad);

(b) the total INCOME of residents of the country derived from the current production of goods and services (income approach to GDP). Such incomes are called FACTOR INCOMES because they accrue to factors of production, and they exclude TRANSFER PAYMENTS like sickness or social security benefits for which no goods or services are received in return. The sum of all these factor incomes (wages and salaries, incomes of the self-employed, etc.) should exactly match the gross domestic product, since each £1’s worth of goods and services produced should simultaneously produce £1 of factor income for their producers. To get from gross domestic factor incomes (= gross domestic product) to gross national factor incomes (= gross national product), it is necessary to add net property income from abroad;

(c) the total domestic expenditure by residents of a country on consumption and investment goods (expenditure approach to GDP). This includes expenditure on final goods and services (excluding expenditure on intermediate products) and includes goods that are unsold and added to stock (inventory investment). However, some domestic expenditure will be channelled to imported goods, while expenditure by nonresidents on goods and services produced by domestic residents will add to the factor incomes of these residents. Thus, to get from total domestic expenditure to total national expenditure (= gross national product), it is necessary to deduct imports and add exports.

Fig. 133 National income accounts. (a) See entry, (b) UK GDP at market prices, 2003 (expenditure method). Note: letters in brackets correspond to the usual AGGREGATE DEMAND (AD). Notation: AD = C + I + G + [X -M]. Source: Office for National Statistics, 2004.

All three measures outlined above show the gross money value of goods and services produced – the gross national product. In the process of producing these goods and services, however, the nation’s capital stock will be subject to wear and tear, so we must allow for the net money value of goods and services produced (allowing for the depreciation of the capital stock or CAPITAL CONSUMPTION) – the NET NATIONAL PRODUCT. This net national product is called national income.

In practice, data-collection problems mean that the three measures of national income give slightly different figures, necessitating the introduction of a residual error term in the national income accounts that reflects these differences. Additionally, in order to highlight the difference in the money and REAL VALUE of national income, it is necessary to take account of the effects of INFLATION upon GNP by applying a broad-based PRICE INDEX, called the GNP-DEFLATOR. See also BLACK ECONOMY.

By way of a ‘practical’ example, Fig. 133 (b) gives a ‘standard’ expenditure-based breakdown of the UK’s gross domestic product (GDP), which is used by the government for economic policy purposes.

national insurance contributions the payments made by employers and their employees to the UK government, on a two-thirds and one-thirds basis respectively, up to a specified maximum limit. National insurance contributions, together with other government budgetary receipts, are used to finance state pensions, social security benefits, the JOBSEEKERS ALLOWANCE, etc. See BUDGET (GOVERNMENT).

![]()

nationalization

The public ownership of industry. In a CENTRALLY PLANNED ECONOMY, most or all of the country’s industries are owned by the state, and resources are allocated, and the supply of goods and services determined, in accordance with a NATIONAL PLAN. In a MIXED ECONOMY, some industries are owned by the state, but the supply of the majority of goods and services is undertaken by PRIVATE-ENTERPRISE industries operating through the MARKET mechanism.

The extent of public ownership of industry depends very much on political ideology, with advocates of a centrally planned economy seeking more nationalization and private-enterprise proponents favouring little or no nationalization. For example, in the UK a Labour government nationalized the iron and steel industry in 1949, having previously nationalized the Bank of England, civil aviation, transport, electricity and the coal and gas industries. The iron and steel industry was denationalized by a Conservative government in 1953, but later a large part of the industry was renationalized by a Labour government in 1967. In 1980 a Conservative government embarked on a major denationalization programme, including British Steel (see PRIVATIZATION).

The main economic justification for nationalization relies heavily on the NATURAL MONOPOLY argument: the provision of some goods and services can be more efficiently undertaken by a monopoly supplier because ECONOMICS OF SCALE are so great that only by organizing the industry on a single-supplier basis can full advantage be taken of cost savings. Natural monopolies are particularly likely to arise where the provision of a good or service requires an interlocking supply network as, for example, in gas, electricity and water distribution, and railway and telephone services. In these cases, laying down competing pipelines and carriageways would involve unnecessary duplication of resources and extra expense. Significant production economics of scale are associated with capital-intensive industries such as iron and steel, gas and electricity generation. In other instances, however, the economic case for nationalization is far less convincing: industries or individual firms may be taken over because they are making losses and need to be reorganized or because of a political concern with preserving jobs. For example, in the UK, the British Leyland car firm and British Ship-builders were nationalized in 1975 and 1977 respectively, only to be returned to private enterprise in the 1980s.

A private-enterprise MONOPOLY could, of course, also secure the same efficiency gains in production and distribution as a state monopoly, but the danger exists that it might abuse its position of market power by monopoly pricing. The state monopolist, by contrast, would seek to promote the interests of consumers by charging ‘fair’ prices. Opponents of nationalization argue, however, that state monopolists are likely to dissipate the cost savings arising from economics of scale by internal inefficiencies (bureaucratic rigidities and control problems giving rise to X-INEFFICIENCY), and the danger is that such inefficiencies could be exacerbated over time by governments subsidizing loss-making activities.

The problem of reconciling supply efficiency with various other economic and social objectives of governments further complicates the picture. For example, the government may force nationalized industries to hold down their prices to help in the control of inflation, but by squeezing the industries’ cash flow the longer-term effects of this might be to reduce their investment programmes. Many of the nationalized industries are charged with social obligations; for example, they may be required by government to provide railway and postal services to remote rural communities, even though these are totally uneconomic.

Thus, assessing the relative merits and demerits of nationalization in the round is a difficult matter. From an economic efficiency point of view, under British COMPETITION POLICY, nationalized industries can be referred for investigation to the COMPETITION COMMISSION to determine whether or not they are operating in the public interest. See MARGINAL COST PRICING, AVERAGE COST PRICING, TWO-PART TARIFF, PUBLIC UTILITY, RATE-OF-RETURN REGULATION, PRIVATIZATION.

![]()

nationalized industry an industry that is owned by the state. See NATIONALIZATION.

national plan a long-term plan for the development of an economy. Such plans usually cover a period of five years or more and attempt to remove bottlenecks to economic development by coordinating the growth of different sectors of the economy by making appropriate investment and manpower planning arrangements. National plans are formulated by government agencies in CENTRALLY PLANNED ECONOMICS and by collaboration between government, industry and trade unions in MIXED ECONOMICS. See also INDICATIVE PLANNING, NATIONAL ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT COUNCIL.

national product the total money value of goods and services produced in a country over a given time period (GROSS NATIONAL PRODUCT). Gross national product less CAPITAL CONSUMPTION or depreciation is Called NET NATIONAL PRODUCT, which is equal to NATIONAL INCOME. See NATIONAL INCOME ACCOUNTS.

National Research and Development Corporation a UK organization that promoted and financially assisted the development and industrial application of INVENTIONS from 1948 to 1981. See BRITISH TECHNOLOGY GROUP, INDUSTRIAL POLICY.

National Vocational Qualification (NVQ) see TRAINING.

natural monopoly a situation where ECONOMICS OF SCALE are so significant that costs are minimized only when the entire output of an industry is supplied by a single producer so that supply costs are lower under MONOPOLY than under conditions of PERFECT COMPETITION and OLIGOPOLY. The natural monopoly proposition is the principal justification for the NATIONALIZATION of industries such as the railways. See MINIMUM EFFECT SCALE.

natural rate of economic growth see HARROD ECONOMIC GROWTH MODEL.

natural rate of unemployment the underlying rate of UNEMPLOYMENT below which it is not possible to reduce unemployment further without increasing the rate of INFLATION. The term ‘natural rate of unemployment’ is often used synonymously with the NON-ACCELERATING INFLATION RATE OF UNEMPLOYMENT (NAIRU).

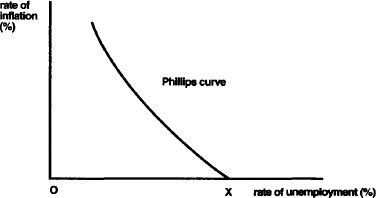

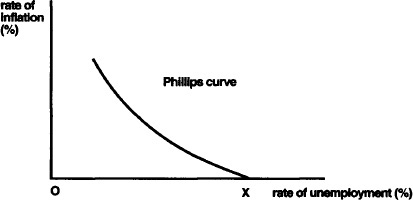

The natural rate of unemployment can be depicted by reference to the PHILLIPS CURVE. In Fig. 134, the rate of unemployment is shown on the horizontal axis and the rate of inflation is shown on the vertical axis, with the Phillips curve showing the ‘trade-off’ between unemployment and inflation. Point X, where the Phillips curve intersects the horizontal axis, depicts the natural rate of unemployment. If unemployment is pushed below the natural rate of unemployment (currently estimated at around 5% in the UK), then inflation starts to accelerate.

The natural rate of unemployment includes FRICTIONAL UNEMPLOYMENT, STRUCTURAL UNEMPLOYMENT and, in particular, ‘voluntary’ unemployment (people who are out of work because they are not prepared to take work at the ‘going’ wage rate). See main UNEMPLOYMENT entry for further discussion.

However, the term ‘natural’ rate of unemployment is somewhat a misnomer insofar as it implies that it is ‘immutable’. This is far from the case, as the natural rate of unemployment can vary between countries and also within countries over time. Structural unemployment, for example, can be reduced by training schemes that improve occupational mobility while ‘voluntary’ unemployment can be reduced by lowering the ‘cushion’ of social security benefits and improving incentives to work (e.g. the Working Families’ Tax Credit Scheme). See EXPECTATIONS-ADJUSTED/AUGMENTED PHILLIPS CURVE.

natural resources the contribution to productive activity made by land (for example, a factory site or farm) and basic raw materials, such as iron ore, timber, oil, corn, etc. Some natural resources, such as wheat, are renewable, while others, such as iron ore, are finite (non-renewable) and will eventually be exhausted. However, as stocks of non-renewable natural resources begin to deplete, their price will tend to rise, providing an incentive to seek other natural or synthetic substitutes for them. Natural resources are one of the three main FACTORS OF PRODUCTION, the other two being LABOUR and CAPITAL. See ECONOMIC GROWTH.

Fig. 134 Natural rate of unemployment. Phillips curve depicting the natural rate of unemployment.

near money any easily saleable (liquid) ASSET that performs the function of MONEY as a STORE OF VALUE but not that of a universally acceptable MEDIUM OF EXCHANGE, CURRENCY (notes and coins) serves as a store of value and, being the most liquid of all assets, is universally accepted as a means of PAYMENT. However, building society deposits, National Savings deposits and Treasury bills are, respectively, less and less readily acceptable in their present form for making payments, and thus function as ‘near money’. See MONEY-SUPPLY DEFINITIONS.

necessary condition a condition that is indispensable for the achievement of an objective. A necessary condition is usually contrasted with sufficient condition, which is viewed as the adequacy of a condition to achieve an objective.

For example, an increase in INVESTMENT is a necessary condition in the achievement of higher rates of ECONOMIC GROWTH, but it is not a sufficient condition to generate growth insofar as other factors, such as an increase in the LABOUR FORCE, also contribute to raising growth rates.

NEDC see NATIONAL ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT COUNCIL.

negative income tax a proposed TAX system aimed at linking the TAXATION and SOCIAL-SECURITY BENEFITS systems for low-income or no-income members of society. This is done by replacing the separate systems for collecting PROGRESSIVE TAXATION and for paying social security benefits by a single system that links the two together by establishing a common stipulated minimum income level, taxing those above it and giving tax credits to those below it.

Proponents of the negative income-tax system point to its advantages in assisting in the removal of the POVERTY TRAP and in making labour markets more flexible. See SUPPLY-SIDE ECONOMICS.

negative or inverse relationship the relationship between two variables where an increase in one variable, such as PRICE, is associated with a decrease in another variable, such as QUANTITY DEMANDED. Compare POSITIVE RELATIONSHIP.

neoclassical economics a school of economic ideas based on the writings of MARSHALL, etc., that superseded CLASSICAL ECONOMIC doctrines towards the end of the 19th century. Frequently referred to as the ‘marginal revolution’, neoclassical economics involved a shift in emphasis away from classical economic concern with the source of wealth and its division between labour, landowners and capitalists towards a study of the principles that govern the optimal allocation of scarce resources to given wants. The principles of DIMINISHING MARGINAL UTILITY and STATIC EQUILIBRIUM ANALYSIS were founded in this new school of economic thought.

neo-Keynesians those economists who tend to support, to a greater or lesser degree, the main thrust of KEYNES’ arguments and who have subsequently revised and built upon the theory Keynes propounded. See DOMAR ECONOMIC GROWTH MODEL, HARROD ECONOMIC GROWTH MODEL.

net book value the accounting value of a FIXED ASSET in a firm’s BALANCE SHEET that represents its original cost less cumulative DEPRECIATION charged to date.

net domestic fixed-capital formation see GROSS DOMESTIC FIXED-CAPITAL FORMATION.

net domestic product the money value of a nation’s annual output of goods and services less CAPITAL CONSUMPTION experienced in producing that output. See NATIONAL INCOME ACCOUNTS.

net national product the GROSS NATIONAL PRODUCT less CAPITAL CONSUMPTION or depreciation. It takes into account the fact that a proportion of a country’s CAPITAL STOCK is used up in producing this year’s output. See NATIONAL INCOME ACCOUNTS.

net present value see DISCOUNTED CASH FLOW.

net profit the difference between a firm’s TOTAL REVENUE and all EXPLICIT COSTS. In accounting terms, net profit is the difference between GROSS PROFIT and the costs involved in running a firm. See PROFIT, PROFIT-AND-LOSS ACCOUNT.

network externalities the increase in the value of a product as more people use it. For example, as the number of people with telephones increases, the value to any individual of owning a telephone is enhanced, since he or she has more people with whom to communicate.

net worth see LONG-TERM CAPITAL EMPLOYED.

new and old paradigm economics the ‘buzzwords’ now used to describe how the economy ‘works’ with regard to ECONOMIC GROWTH, UNEMPLOYMENT and INFLATION. The ‘old’ paradigm, drawing heavily on the PHILLIPS CURVE and charting the experiences of many advanced industrial countries in the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s, postulates that attempts to promote faster economic growth and reduced unemployment inevitably results in higher inflation. (See Fig. 190 (a), UNEMPLOYMENT). By contrast, the ‘new’ paradigm is based on the experiences of the USA (and the UK) in the 1990s when economic growth brought with it lower unemployment and lower inflation. Proponents of the ‘new’ paradigm postulate that globalization and advances in information technology have brought about permanent and fundamental changes to the USA economy and its sustainable growth rate. The combination of globalization (increased international competition) and the rise of ‘knowledge-based’ industries (telecommunications, electronics and computing and trading through the INTERNET) has increased PRODUCTIVITY and brought with it lower prices. In sum, the economy can grow at a faster sustainable rate without stoking up inflation.

Is this a temporary ‘blip’ or a major shift in the way modern economics work? If the latter, why hasn’t it happened in Europe, especially Germany, France and Italy, where although inflation is low, economic growth is stagnating and unemployment remains high? Proponents of the ‘new’ paradigm answer this by suggesting that the ‘gateway’ to achieving the virtuous circle of growth and low unemployment and inflation in addition to globalization and information technology is more flexible labour markets and the removal of other supply-side deficiencies. The USA and the UK have rapidly moved in this direction whereas Germany and the others have not. See NEW ECONOMY/NEW ECONOMY COMPANY, SUPPLY-SIDE ECONOMICS.

New Deal a government programme introduced in 1998 aimed at reducing youth UNEMPLOYMENT and long-term unemployment amongst older workers. Persons qualifying for the youth scheme must be aged between 18 and 24 and have received the JOBSEEKERS ALLOWANCE for at least six months. Participants in the scheme are offered support and advice in seeking paid work for four months (the ‘Gateway’ period). After this, if they are still unemployed, they are placed on one of four options: (1) subsidized employment; (2) work with a voluntary organization; (3) work with an environmental task force (each of these options lasts six months); or (4) a one-year training or education course. Persons qualifying for the long-term unemployed scheme must be aged 25 or over and have received the jobseekers allowance for at least two years. See SUPPLY-SIDE ECONOMICS.

new economy/new economy company a term used to describe that part of the ECONOMY (and companies operating therein) that is based on new, innovative technologies and delivery systems, utilizing COMPUTERS and the INTERNET. The new economy embraces activities such as telecommunications (e.g. mobile phones, digital television, e-mail), computer software (e.g. Microsoft’s ‘Windows’ system), biotechnology and genetic engineering to produce new drugs and ‘genetically modified’ (GM) foodstuffs, and the‘dot.com’ companies providing Internet access and facilities. By contrast, the ‘old economy’ consists of older established companies producing, for example, beer, cigarettes and food.

Of course, at the margin the distinction between the two is somewhat arbitrary since ‘old economy’ companies have embraced the new technologies in order to upgrade their manufacturing systems and widen their marketing reach. For example, car companies use robots on automated, computerized production lines to produce their models, while traditional services areas such as banking and insurance have developed telephone and Internet banking and insurance facilities to augment their branch networks. See NEW AND OLD PARADIGM ECONOMICS.

New International Economic Order (NIEO) an economic and political concept that advocates the need for fundamental changes in the conduct of INTERNATIONAL TRADE and ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT to redress the economic imbalance between the DEVELOPED COUNTRIES and the DEVELOPING COUNTRIES. The UNITED NATIONS responded to the call of developing countries for such a change by issuing in 1974 a Declaration and Programme of Action on the Establishment of a New Inter-national Economic Order that laid down principles and measures designed to improve the relative position of the developing countries. These initiatives have centred on the promotion of schemes such as:

(a) INTERNATIONAL COMMODITY AGREEMENTS to support developing countries’ primary-produce exports;

(b) the negotiation of special trade concessions to enable developing countries’ manufactured exports to gain greater access to the markets of the developed countries;

(c) the encouragement of a financial and real resource transfer programme of ECONOMIC AID;

(d) an increase in economic cooperation between the developing countries.

These aspirations have been pursued primarily through the UNITED NATIONS CONFERENCE ON TRADE AND DEVELOPMENT but as yet have met with little success.

new-issue market see CAPITAL MARKET.

newly industrializing country a DEVELOPING COUNTRY that has moved away from exclusive reliance on primary economic activities (mineral extraction and agricultural and animal produce) by establishing manufacturing capabilities as a part of a long-term programme of INDUSTRIALIZATION. Brazil, Mexico and Hong Kong are examples of a newly industrializing country. See STRUCTURE OF INDUSTRY, ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT.

new product a good or service that is sufficiently different from existing products to be regarded as ‘new’ by consumers. The degree of ‘newness’ of a product depends upon the extent of its novelty and whether it embodies product attributes not previously available and can range from relatively minor adaptations of existing products to entirely different product offerings, like microwave ovens. A product that is significantly novel can give a supplier a major PRODUCT DIFFERENTIATION advantage over competitors. As such, developing new products (see PRODUCT DEVELOPMENT) is an important area of non-price competition in OLIGOPOLY.

new protectionism the use of various devices, such as EXPORT RESTRAINT AGREEMENTS, LOCAL CONTENT requirements and import licensing arrangements, that serve to restrict INTERNATIONAL TRADE. See WORLD TRADE ORGANIZATION, PROTECTIONISM, BEGGAR-MY-NEIGHBOUR POLICY.

NIC see NEWLY INDUSTRIALIZING COUNTRIES.

nineteen ninety-two (1992) see EUROPEAN UNION, SINGLE EUROPEAN ACT.

nominal exchange rate the EXCHANGE RATE of a currency expressed in current price terms, that is, making no allowance for the effects of INFLATION. Contrast REAL EXCHANGE RATE.

nominal interest rate the INTEREST RATE paid on a LOAN without making any adjustment for the effects of INFLATION. Contrast REAL INTEREST RATE.

nominal price the PRICE of a PRODUCT or FINANCIAL SECURITY measured in terms of current prevailing price levels, that is, making no allowance for the effects of INFLATION. Contrast REAL PRICE. See PAR VALUE.

nominal rate of protection the actual amount of PROTECTION accorded to domestic suppliers of a final product when a TARIFF is applied to a competing imported final product. For example, assume that initially the same domestic product and imported product are both priced at £100. If an AD VALOREM TAX of 10% is now applied to the imported product, its price will increase to £110. This allows domestic VALUE ADDED (and prices) to rise by up to £10 with the domestic product still remaining fully competitive with the imported product. The nominal rate of protection accorded to domestic suppliers is thus 10% of the price of the imports. Compare EFFECTIVE RATE OF PROTECTION.

nominal chare capital see AUTHORIZED SHARE CAPITAL.

nominal values the measurement of an economic aggregate (for example GROSS DOMESTIC PRODUCT) in terms of current prices. Because of price changes from year to year, observations based on current prices can obscure the underlying real trend. Contrast REAL VALUE.

nominee holding the SHARES in a JOINT-STOCK COMPANY that are held under the names of a token shareholder on behalf of their ultimate owners. Nomi-nee holdings are used where a person or institution wishes to keep secret the extent of their shareholding in a company, often as a prelude to a TAKEOVER initiative.

nonaccelerating inflation rate of unemployment (NAIRU) the underlying rate of UNEMPLOYMENT that is consistent with stable prices (i.e. below which it is not possible to reduce unemployment further without increasing the rate of inflation). The term NAIRU is often used synonymously with the NATURAL RATE OF UNEMPLOYMENT.

The NAIRU can be depicted by reference to the PHILLIPS CURVE. In Fig. 135 the rate of unemployment is shown on the horizontal axis and the rate of inflation is shown on the vertical axis with the Phillips curve showing the ‘trade-off’ between unemployment and inflation. Point X, where the Phillips curve intersects the horizontal axis, depicts the NAIRU. See NATURAL RATE OF UNEMPLOYMENT for further discussion.

It is to be noted that the rate of inflation associated with any given level of unemployment may itself accelerate as a result of inflationary EXPECTATIONS, with labour market participants adjusting their behaviour (in particular demanding higher money wage rates) to offset higher anticipated inflation. See EXPECTATIONS- ADIUSTED/AUGMENTED PHILLIPS CURVE.

Fig. 135 Nonaccetcrating inflation rate of unemployment (NAIRU). Phillips curve depicting the NAIRU.

nondiscretionary competition policy an approach to the control of MONOPOLY that involves the stipulation of ‘acceptable’ standards of MARKET STRUCTURE and MARKET CONDUCT and prohibits outright any breach of these standards. See COMPETITION POLICY.

nondurable good a CONSUMER GOOD, such as a vegetable, or some CAPITAL GOOD, such as a casting mould, that is used up in a single time period rather than over a relatively long time period. Contrast DURABLE GOOD.

non-excludability see COLLECTIVE PRODUCTS.

non-exhaustible natural resources see NATURAL RESOURCES.

nonmarketed economic activity any economic activity that, although usually legal, is not recorded in the NATIONAL INCOME ACCOUNTS of a nation. The labour and other inputs used in such activities are not paid a cash price for the work done and are therefore unrecorded. Examples of such activities are unpaid cooking and cleaning by housewives and unpaid charity work by voluntary organizations. Such omissions distort international comparisons of gross national income figures, not least because rural areas tend to be more self-sufficient while urbanized countries tend to purchase what they need rather than making it themselves (e.g. milk, bread, etc.). See BLACK ECONOMY.

nonprice competition see COMPETITION METHODS, PRODUCT DIFFERENTIATION.

non-profit-making organization any organization that has primary objectives other than the making of PROFIT, for example, a charitable trust.

non-ranewable natural resources see NATURAL RESOURCES.

non rival see COLLECTIVE PRODUCTS.

non-tariff barrier see IMPORT RESTRICTION.

nontraded product 1 a product that cannot be traded under any circumstance because no markets for such products exist, for example, COLLECTIVE PRODUCTS like defence.

2 a product that cannot be traded outside a certain limited geographical area because its bulk or weight makes it prohibitively expensive to transport and trade internationally, for example, gravel and bricks.

non-zero sum game a situation in GAME THEORY where game players, by choosing appropriate strategies, can collectively increase the total payoff available to all players. For example, by collaborating over their advertising and promotion, two firms may be able to expand the total market for a product so that both are able to increase their sales and profits.

normal product a good or service for which the INCOME-ELASTICITY OF DEMAND is positive, that is, as income rises, buyers purchase more of the product. Consequently, when the price of such a product falls, thereby effectively increasing consumers’ real income, then that price cut will have the INCOME EFFECT of tending to increase quantity demanded. This will tend to reinforce the SUBSTITUTION EFFECT of a price cut, which will cause consumers to buy more of the product because it is now relatively cheaper.

This applies to most products, with the exception of INFERIOR PRODUCTS, where the income effect is negative. See PRICE EFFECT.

normal profit a PROFIT that is just sufficient to ensure that a firm will continue to supply its existing good or service. In the THEORY OF MARKETS, firms’ COST curves thus include normal profit as an integral part of supply costs (see ALLOCATIVE EFFICIENCY).

If the level of profit earned in a particular market is too low to generate a return on capital employed comparable to that obtainable in other equally risky markets, then the firm’s resources will be transferred to some other use. See OPPORTUNITY COST, MARKET EXIT, ABOVE-NORMAL PROFIT.

normative economics the study of what ‘ought to be’ in economics rather than what ‘is’. For example, the statement that ‘people who earn high incomes ought to pay more income tax than people who earn low incomes’ is a normative statement. Normative statements reflect people’s subjective value judgements of what is good or bad and depend on ethical considerations such as ‘fairness’ rather than strict economic rationale. The actual economic effects of a taxation structure that taxes the rich more heavily than the poor (on spending and saving, for example) is a matter for POSITIVE ECONOMICS. See WELFARE ECONOMICS.

North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) a regional FREE-TRADE AREA established in 1989 by the USA and Canada. NAFTA set about removing tariffs on most manufactured goods, raw materials and agricultural produce over a 10-year period, as well as restrictions on cross-border investment, banking and financial services. Mexico joined NAFTA in 1993 with the aim of removing tariffs between Mexico and the other two countries by 2009.

NAFTA has a similar market size (population 414 million) as that of the EUROPEAN UNION. See TRADE INTEGRATION.

null hypothesis see HYPOTHESIS TESTING.

numeraire a monetary unit that is used as the basis for denominating international exchanges in a product or commodity, and financial settlements, on a common basis. For example, the US DOLLAR is used as the numeraire of the oil trade, and the SPECIAL DRAWING UNIT is used as the numeraire of the internal financial transactions of the INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND.

NVQ (National Vocational Qualification) see TRAINING.