OECD see ORGANIZATION FOR ECONOMIC COOPERATION AND DEVELOPMENT

off-balance shoot financing the payment for use of an ASSET by hiring (LEASING) it rather than buying it. If a company wishes to install a new £50,000 photocopier, it may enter into a lease agreement and agree to pay £12,000 per year over five years rather than buy the copier. Each year, £12,000 is charged against profits in the company’s PROFIT-AND-LOSS ACCOUNT. The copier does not appear in the BALANCE SHEET as a FIXED ASSET because the firm does not own it but shows up as an annual operating cost that may be offset against PROFIT for TAXATION purposes. Off-balance sheet financingenables a company to make use of expensive assets without having to invest large sums of money to buy them. It also enables a company to keep its LONG-TERM CAPITAL EMPLOYED as small as possible, improving its measured RETURN ON CAPITAL EMPLOYED. See LEASE-BACK.

offer curve see EDGEWORTH BOX.

offer for sale a method of raising new SHARE CAPITAL by issuing company shares to the general public at a prearranged fixed price. See SHARE ISSUE.

Office for National Statistics (ONS) the UK government agency responsible for the collection, analysis and publication of economic, social and demographic statistics, including the consumer price index, national income accounts, balance-of-payments accounts, social trends, labour market data and periodic censuses of the population and health statistics.

ONS was formed in 1996 from the merger of the Central Statistical Office and the Office of Population Censuses and Surveys.

offer-for-sale by tender a method of raising new SHARE CAPITAL by issuing company shares to the general public at a price that is determined by the strength of investment demand for it, subject to a minimum price bid. See SHARE ISSUE.

Office of Fair Trading (OFT) an authority established by the FAIR TRADING ACT 1973 to administer all aspects of UK COMPETITION POLICY, specifically the control of MONOPOLIES/MARKET DOMINANCE, MERGERS and TAKEOVERS, ANTICOMPETITIVE AGREEMENTS/RESTRICTIVE TRADE AGREEMENTS, RESALE PRICES and ANTI-COMPETITIVE PRICES. The OFT, headed by the Director General of Fair Trading, collects data on industrial structure, monitors changes in market concentration and merger and takeover activity, and investigates and acts on information received from interested parties concerning allegedly ‘abusive’ behaviour in respect of trade practices, prices, discounts and other terms and conditions of sale. Where appropriate, the OFT may decide to refer particular cases for further investigation and report to the COMPETITION COMMISSION. The Office of Fair Trading also has other main responsibilities with regard to the protection of consumers’ interests generally, including taking action against unscrupulous trade practices, such as false descriptions of goods and inaccurate weights and measures, and the regulation of consumer credit. See CONSUMER PROTECTION, TRADE DESCRIPTIONS ACT 1968, 1972, WEIGHTS AND MEASURES ACT 1963, CONSUMER CREDIT ACT 1974.

official financing see BALANCE OF PAYMENTS.

Official List the prices of STOCKS and SHARES published daily by the UK STOCK EXCHANGE. The prices quoted are the prices ruling at the close of the day’s trading and are based on the average of the bid and offer prices. See BID PRICE.

OFT see OFFICE OF FAIR TRADING.

old economy/old economy company see NEW ECONOMY/NEW ECONOMY COMPANY.

![]()

oligopoly

A type of MARKET STRUCTURE that is characterized by:

(a) few firms and many buyers, that is, the bulk of market supply is in the hands of a relatively few large firms who sell to many small buyers.

(b) homogeneous or differentiated products, that is, the products offered by suppliers may be identical or, more commonly, differentiated from each other in one or more respects. These differences may be of a physical nature, involving functional features, or may be purely ‘imaginary’ in the sense that artificial differences are created through ADVERTISING and SALES PROMOTION (see PRODUCT DIFFERENTIATION).

(c) difficult market entry, that is, high BARRIERS TO ENTRY, which make it difficult for new firms to enter the market.

The primary characteristic associated with the condition of ‘fewness’ is known as MUTUAL INTERDEPENDENCE. Basically, each firm, when deciding upon its price and other market strategies, must explicitly take into account the likely reactions and countermoves of its competitors in response to its own moves. A price cut, for example, may appear to be advantageous to one firm considered in isolation, but if this results in other firms also cutting their prices to protect sales, then all firms may suffer reduced profits. Accordingly, oligopolists tend to avoid price competition, employing various mechanisms (PRICE LEADERSHIP, CARTELS) to coordinate their prices. See COLLUSION.

Oligopolists compete against each other using various product differentiation strategies (advertising and sales promotion, new product launches) because this preserves and enhances profitability –price cuts are easily matched whereas product differentiation is more difficult to duplicate, thereby offering the chance of a more permanent increase in market share; differentiation expands sales at existing prices or the extra costs involved can be ‘passed on’ to consumers; differentiation by developing brand loyalty to existing suppliers makes it difficult for new firms to enter the market.

Traditional (static) market theory shows oligopoly to result in a ‘MONOPOLY-like’ suboptimal MARKET PERFORMANCE: output is restricted to levels below cost minimization; inefficient firms are cushioned by a ‘reluctance’ to engage in price competition; differentiation competition increases supply costs; prices are set above minimum supply costs, yielding oligopolists ABOVE-NORMAL PROFITS that are protected by barriers to entry. As with monopoly, however, this analysis makes no allowance for the contribution that ECONOMIES OF SCALE may make to the reduction of industry costs and prices and the important contribution of oligopolistic competition to INNOVATION and NEW PRODUCT development. See KINKED-DEMAND CURVE, LIMIT-PRICING, PERFECT COMPETITION, MONOPOLISTIC COMPETITION, DUOPOLY, GAME THEORY, REVISED SEQUENCE, COMPETITION POLICY (UK).

![]()

oligopsony a form of BUYER CONCENTRATION, that is, a MARKET situation in which a few large buyers confront many small suppliers. Powerful buyers are often able to secure advantageous terms from suppliers in the form of BULK-BUYING price discounts and extended credit terms. See also OLIGOPOLY, BILATERAL OLIGOPOLY, COUNTERVAILING POWER.

ONS see OFFICE FOR NATIONAL STATISTICS.

OPEC see ORGANIZATION OF PETROLEUM EXPORTING COUNTRIES.

open economy an economy that is heavily dependent on INTERNATIONAL TRADE, EXPORTS and IMPORTS being large in relation to the size of that economy’s NATIONAL INCOME. For such economies, analysis of the CIRCULAR FLOW OF NATIONAL INCOME must allow for the influence of exports and imports. Compare CLOSED ECONOMY.

open-market operation an instrument of MONETARY POLICY involving the sale or purchase of government TREASURY BILLS and BONDS as a means of controlling the MONEY SUPPLY. If, for example, the monetary authorities wish to increase the money supply, then they will buy bonds from the general public. The money paid out to the public will increase their bank balances. As money flows into the banking system, the banks’ liquidity is increased, enabling them to increase their lending. This results in the multiple creation of new bank deposits and, hence, an expansion of the money supply. See BANK-DEPOSIT CREATION, RESERVE ASSET RATIO, FUNDING.

opportunism a situation in which one party to a CONTRACT is able to take advantage of the other party or parties to the contract. See ASYMMETRICAL INFORMATION, ADVERSE SELECTION, MORAL HAZARD.

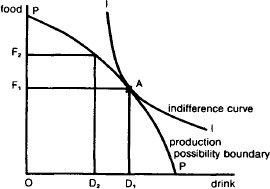

opportunity cost or economic cost a measure of the economic cost of using scarce resources (FACTOR INPUTS) to produce one particular good or service in terms of the alternatives thereby foregone. To take an example, if more resources are used to produce food, fewer resources are then available to provide drinks. Thus, in Fig. 136, the PRODUCTION POSSIBILITY BOUNDARY (PP) shows the quantity of food and drink that can be produced with society’s scarce resources. If society decides to increase production of food from OF1 to OF2, then it will have fewer resources to produce drinks, so drink production will decline from OD1, to OD2. The slope of the production-possibility boundary shows the MARGINAL RATE OF TRANSFORMATION (the ratio between the MARGINAL COST of producing one good and the marginal cost of producing the other). In practice, not all resources can be readily switched from one end use to another (see SUNK COSTS).

In the same way, if a customer with limited income chooses to buy more of one good or service, he can only do so by forgoing the consumption of other goods or services. His preferences between food and drink are reflected in his INDIFFERENCE CURVE II in Fig. 136. The slope of the indifference curve shows the consumer’s MARGINAL RATE OF SUBSTITUTION (how much of one good he is prepared to give up in order to release income that can be used to acquire an extra unit of the other good).

If the indifference curve II is typical of all consumers’ preferences between food and drink, then society would settle for OF1 of food and OD1 of drinks, for only at point A would the opportunity cost of deploying resources (the slope of PP) correspond with the opportunity cost of spending limited income (the slope of II). See also PARETO OPTIMALITY, ECONOMIC RENT.

optimal factor combination see DIMINISHING RETURNS.

optimal scale see PRODUCTIVE EFFICIENCY.

optimizing the maximization of society’s economic welfare in respect of the macroeconomic objectives of FULL EMPLOYMENT, PRICE STABILITY, ECONOMIC GROWTH and BALANCE-OF-PAYMENTS EQUILIBRIUM.

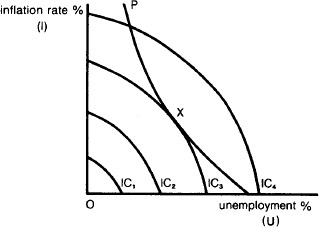

The essence of this approach can be illustrated, to simplify matters, by reference to the PHILLIPS CURVE‘trade-off’ between unemployment (U) and inflation (I). The Phillips curve in Fig. 137 shows that as unemployment falls, inflation increases and vice-versa. See MACROECONOMIC POLICY, FIXED TARGETS, INTERNAL-EXTERNAL BALANCE MODEL.

Fig. 136 Opportunity cost. See entry.

optimum the best possible outcome within a given set of circumstances. For example, in the theory of CONSUMER EQUILIBRIUM, a consumer with a given income and facing set prices for products will adjust the purchases of these products so as to maximize the utility or satisfaction to be derived from spending his or her limited income. Similarly, in the THEORY OF THE FIRM, a business confronted by a given market price for its product will adjust its output of that product so as to maximize its profits. See also PROFIT MAXIMIZATION, OPTIMIZING, PARETO OPTIMALITY.

Fig. 137 Optimizing. The Phillips curve is drawn as P. The economic welfare of society is represented by a family of INDIFFERENCE CURVES IC1, IC2, IC3, IC4, each indicating successively higher levels of economic welfare as the origin, O, is approached. The optimum point is at the origin, because here full employment and complete price stability are theoretically simultaneously attained. However, the Phillips curve sets a limit to the combinations of U and I that can be achieved in practice. Given this constraint, the task of the authorities is to select that combination of U and I that maximizes society’s economic welfare. This occurs at point X, where the Phillips curve is tangential to indifference curve IC3.

optimum order quantity see STOCKHOLDING COSTS.

option a contractual right to buy or sell a COMMODITY (rubber, tin, etc.), a FINANCIAL SECURITY (share, stock, etc.) or a FOREIGN CURRENCY at an agreed (predetermined) price at any time within three months of the contract date. Options are used by buyers and sellers of commodities, financial securities and foreign currencies to offset the effects of adverse price movements of these items. For example, a producer of chocolate could purchase an option to buy a standard batch of cocoa at an agreed price of, say, £500 per tonne. If the market price of cocoa rises above £500 per tonne over the next three months before the option expires, then the chocolate producer will find it worthwhile to exercise his option to buy the cocoa at £500. If the price falls below £500, then the chocolate producer can choose not to exercise the option but instead to buy at the cheaper current market price. The chocolate producer pays, say, £50 for the buy or ‘call’ option in order to protect himself from significant price rises for cocoa (a sort of insurance against adverse price movements). Similarly, growers of cocoa can enter into a sell or ‘put’ option to cover themselves against falling cocoa prices. For example, if a cocoa grower enters into an option to sell a standard batch of cocoa at an agreed price of £500 per tonne and the price falls, he will exercise his option to sell at £500 per tonne, but if the price rises above £500 per tonne, he will choose to sell his cocoa at the higher market price and allow the option to lapse. The cocoa grower would pay, say, £50 for the sell or ‘put’ option in order to protect himself from significant price falls in cocoa. In between the buyers and producers of cocoa are the specialist dealers who draw up option contracts and decide option prices in the light of current and anticipated prices of cocoa.

In addition to options that are bought and sold to underpin a normal trading transaction, some options are bought and sold by speculators (see SPECULATION) seeking to secure windfall profits. Options are traded on the FUTURES MARKET, especially the LONDON INTERNATIONAL FINANCIAL FUTURES EXCHANGE. See DERIVATIVE. See also EXECUTIVE SHARE OPTION SCHEME.

ordinal utility the (subjective) UTILITY or satisfaction that a consumer derives from consuming a product, measured on a relative scale. Ordinal utility measures acknowledge that the exact amount of utility derived from consuming products cannot be measured in discrete units, as implied by CARDINAL UTILITY measures. Ordinal measures instead involve the consumer ordering his or her preference for products, ranking products in terms of which product yields the greatest satisfaction (first choice), which product then yields the next greatest satisfaction (second choice), and the product which then yields the next greatest satisfaction (third choice), and so on. Such ordinal rankings give a clear indication about consumer preferences between products but do not indicate the precise magnitude of satisfaction as between the first and second choices and the second and third choices, etc.

Ordinal utility measures permit consumer preferences between two products to be shown in the form of INDIFFERENCE CURVES which depict various combinations of the two products that yield equal satisfaction to the consumer. Assuming ‘rational’ consumer behaviour (see ECONOMIC MAN), a consumer will always choose to be on the highest possible indifference curve, although the increase in satisfaction to be derived from moving from a lower to a higher indifference curve cannot be exactly determined. Nevertheless, INDIFFERENCE MAPS can be used to construct DEMAND CURVES. See DIMINISHING MARGINAL UTILITY.

ordinary least squares see REGRESSION ANALYSIS.

ordinary shares or equity a FINANCIAL SECURITY issued to those individuals and institutions who provide long-term finance for JOINT-STOCK COMPANIES. Ordinary SHAREHOLDERS are entitled to any net profits made by their company after all expenses (including interest charges and tax) have been paid, and they generally receive some or all of these profits in the form of DIVIDENDS. In the event of the company being wound up (see INSOLVENCY), they are entitled to any remaining ASSETS of the business after all debts and the claims of PREFERENCE SHAREHOLDERS have been discharged. Ordinary shareholders generally have voting rights at company ANNUAL GENERAL MEETINGS, which depend upon the number of shares that they hold. See also SHARE CAPITAL.

organic growth (internal growth) a mode of business growth that is self-generated (that is, expansion from within) rather than achieved externally through MERGERS and TAKEOVERS. Organic growth typically involves a firm in improving its market share by developing new products and generally outperforming competitors (see HORIZONTAL INTEGRATION) and through market development (that is, finding new markets for existing products). Organic growth may also involve firms in expanding vertically into supply sources and market outlets (see VERTICAL INTEGRATION) as well as DIVERSIFICATION into new product areas.

The advantages of organic growth include the ability to capitalize on the firm’s existing core skills and knowledge, use up spare production capacity and more closely match available resources to the firm’s expansion rate over time. Internal growth may be the only alternative where no suitable acquisition exists or where the product is in the early phase of the PRODUCT LIFE CYCLE. The disadvantages of organic growth are that in relying too extensively on internally generated resources, the firm may fail to develop acceptable products to sustain its position in existing markets, while existing skills and know-how may be too limited to support a broader-based expansion programme.

For this reason, firms often rely on a combination of internal and external growth modes to internationalize their operations and undertake product/market diversifications. See EXTERNAL GROWTH, BUSINESS STRATEGY, PRODUCT MARKET MATRIX, NEW PRODUCT DEVELOPMENT.

organization the structure of authority or power within a FIRM or public body. Generally, there will be a number of management levels in an organization, with a chief executive at the top of the pyramid-shaped organization and increasing numbers of senior, middle and junior managers further down the hierarchy, operatives, sales people and clerks forming the base of the pyramid. Lines of authority are established by the organization’s structure, with orders being transmitted downwards in increasing detail and information feedback being transmitted upwards.

In the traditional THEORY OF THE FIRM, such organizational details are ignored, the firm being portrayed as a simple decision-making unit that responds exactly to orders initiated by its controlling ENTREPRENEUR. In practice, the structure and operations of large, complex organizations themselves will affect the decision-making process and the specification of organization objectives. See ORGANIZATION THEORY, BEHAVIOURAL THEORY OF THE FIRM, M-FORM ORGANIZATION, U-FORM ORGANIZATION, CORPORATE RE-ENGINEERING.

organizational slack any organizational resources devoted to the satisfaction of claims by managers of subunits within the business organization in excess of the resources that these subunits need to complete company tasks. Organizations tend to build up a degree of ‘organizational slack’, or ‘managerial slack’, where they operate in less competitive, oligopolistic markets (see OLIGOPOLY) in the form of excess staffing, etc., and this slack provides a pool of emergency resources that the organization can draw upon during bad times. When confronted with a deterioration in the economic environment, the organization can exert pressure on subunits within the organization to trim organizational slack and allow the organization to continue to achieve its main goals. Faced with increasing market competition, the organization will increasingly be run as a ‘tight ship’ as slack is trimmed until, in the limiting case of PERFECT COMPETITION, organizational slack will be zero and PROFIT MAXIMIZATION becomes the rule.

The concept of organizational slack is a particular feature of the BEHAVIOURAL THEORY OF THE FIRM and is similar in many respects to the concept of X-INEFFICIENCY. See also PRODUCTIVITY.

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) an international organization whose membership comprises mainly the economically advanced countries of the world. The OECD provides a regular forum for discussions amongst government finance and trade ministers on economic matters affecting their mutual interests, particularly the promotion of economic growth and international trade, and it coordinates the provision of ECONOMIC AID to the less developed countries. The OECD is a main source of international economic data and regularly compiles and publishes standardized inter-country statistics.

Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) an organization established in 1960 with a head office in Vienna to look after the oil interests of five countries: Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia and Venezuela. By 1973, a further eight countries had joined the OPEC ranks: Qatar, Indonesia, Libya, Abu Dhabi, Algeria, Nigeria, Ecuador and Gabon. Ecuador withdrew in 1992 and Gabon in 1995.

In 1973 OPEC used its power to wrest the initiative in administering oil prices away from the American oil corporations, and the price of oil quadrupled from $2.5 (American dollars) a barrel to over $11.50 a barrel. The effect of this was to produce balance-of-payments deficits in most oil-consuming countries and with it a period of protracted world recession. As the recession bit, oil revenues began to fall, to which OPEC responded by increasing prices sharply again in 1979 from under $15 a barrel to around $28 a barrel.

OPEC is often cited as an example of a successful producers’ CARTEL. In a ‘classical’ cartel market, supply is deliberately restrained in order to force prices up by allocating production QUOTAS to each member. Interestingly, in OPEC’s case, because of political difficulties, formal quotas were not introduced until 1982, but these had limited success because of ‘cheating’. The main reason it has been able to successfully increase prices in the past has been that the demand for oil is highly price inelastic. Recently, however, OPEC has been under pressure for two reasons:

(a) the total demand for oil has fallen, partly as a result of the world recession but also because its high price has made it economical to substitute alternative forms of energy (coal, in particular) so that oil is now less price inelastic than formerly;

(b) the increased profitability of oil production has led to a high rate of investment in new oil fields (the North Sea, in particular), and this has weakened the control of OPEC over world supplies. In 2001 OPEC accounted for around 40% of world oil production, compared to over 75% in the 1970s. Apart from a substantial rise in oil prices at the time of the Gulf War in 1991, oil prices remained depressed in the 1990s, falling to under $10 a barrel in 1997. The introduction of stronger production quotas in 1999, however, led to a sharp increase in oil prices to over $30 a barrel, and rising demand led to further price increases over the period 2000–05 (currently $54 a barrel as at April 2005).

organization theory a behavioural framework for the analysis of decision-making processes within large complex ORGANIZATIONS. Economic analysis frequently considers a FIRM to be a single autonomous decision-making unit seeking to maximize profit. By contrast, organization theory suggests that in large organizations decisions are often decentralized, that decisions are influenced by other than economic motives and that the decision process is influenced by the company’s internal structure, or organization. Nonoptimal or satisficing decisions are the result, rather than profit maximizing. See PROFIT-MAXIMIZATION, FIRM OBJECTIVES, SATISFICING THEORY, BEHAVIOURAL THEORY OF THE FIRM.

original income the INCOME received by a household (or person) before allowing for any payment of INCOME TAX and other taxes, and the receipt of various TRANSFER PAYMENTS (social security benefits, etc.). Compare FINAL INCOME. See PERSONAL DISTRIBUTION OF INCOME, REDISTRIBUTION OF INCOME PRINCIPAL OF TAXATION.

output the GOODS and SERVICES that are produced using a combination of FACTOR INPUTS.

output-approach to GDP see NATIONAL INCOME ACCOUNTS.

output gap see DEFLATIONARY GAP.

output per man hour see PRODUCTIVITY.

outside money see EXOGENOUS MONEY.

outsider-insider model see INSIDER-OUTSIDER MODEL.

outsourcing the buying-in of components, finished products and services from outside the firm rather than self-supply from within the firm. In some cases this is done because it is more cost-effective to use outside suppliers or because outside suppliers are more technically competent or can supply a greater range of items. For example, in 2000 the Bank of Scotland signed a 10-year outsourcing agreement with IBM that involved IBM taking over the Bank of Scotland’s computer systems and operating them. The deal enabled the Bank of Scotland to ‘save’ up to £150 million on its information technology (IT) costs as well as being able to draw on IBM’s expertise to create a more technically advanced IT infrastructure than it could have achieved on its own.

On the debit side, however, reliance on outside suppliers may make the firm vulnerable to disruptions in supplies, particularly missed delivery dates, problems with the quality of bought-in components, and ‘unreasonable’ terms and conditions imposed by powerful suppliers. The decision to produce internally or outsource will depend upon the combined production costs and TRANSACTION COSTS of the alternative supply source. See TRANSACTION, INTERNALIZATION, MAKE OR BUY, VERTICAL INTEGRATION.

overcapacity see EXCESS CAPACITY.

overdraft see BANK LOAN.

overheads or indirect costs any COSTS that are not directly associated with a product, that is, all costs other than DIRECT MATERIALS cost and DIRECT LABOUR cost. Production overheads (factory overheads) include the cost of other production expenses, like factory heat, light and power and depreciation of plant and machinery. The cost of factory departments, such as maintenance, materials’ stores and the canteen, that render services to producing departments are similarly part of production overheads, SELLING COSTS and DISTRIBUTION COSTS, and all administration costs, are also counted as overheads since they cannot be directly related to units of product. See also FIXED COSTS.

overmanning the employment of more LABOUR than is strictly required to efficiently undertake a particular economic activity. This can arise through bad work organization on the part of management or through trade union-instigated RESTRICTIVE LABOUR PRACTICES.

overseas investment see FOREIGN INVESTMENT.

oversubscription a situation in which the number of SHARES applied for in a new SHARE ISSUE exceeds the numbers to be issued. This requires the ISSUING HOUSE responsible for handling the share issue to devise some formula for allocating the shares. By contrast, undersubscription occurs when the number of shares applied for falls short of the number on offer, requiring the issuing house that has underwritten the shares to buy the surplus shares itself. See CAPITAL MARKET.

overtime the hours of work that are additional to those formally agreed with the labour force as constituting the basic working week. Employers resort to overtime working to meet sudden increases in business activity, viewing overtime by the existing labour force as a more flexible alternative to taking on extra workers. Overtime pay rates can be two to three times basic hourly rate. See PAY.

overtrading a situation where a FIRM expands its production and sales without making sufficient provision for additional funds to finance the extra WORKING CAPITAL needed. Where this happens, the firm will run into LIQUIDITY problems and can find itself unable to find the cash to pay suppliers or wages. See CASH FLOW.

overutilized capacity a situation in which a plant is operated at output levels beyond the output level at which short-run AVERAGE COST is at a minimum. See DIMINISHING RETURNS, RETURNS TO THE VARIABLE FACTOR INPUT.

‘own-label’ brand a product that is sold by a RETAILER and that bears the retailer’s own BRAND name. In some cases, own-label brands are manufactured by the retailer as part of a vertically integrated manufacturing-retailing operation (Boots the Chemist, for instance, both produces and retails a large number of its own pharmaceutical and cosmetic products). More usually, however, retailers’ own-labels are produced by independent manufacturers on a contract basis. Retailers use own-label brands in order to provide greater control and flexibility over their product/price mix and to build up customer loyalty to their stores, so that customers will tend to frequent the one store rather than ‘shop around’.