factor 1 a FACTOR INPUT that is used in production (see NATURAL RESOURCES, LABOUR, CAPITAL).

2 a business that buys in bulk and performs a WHOLESALING function.

3 a business that buys trade debts from client firms (at some agreed price below the nominal value of the debts) and then arranges to recover them for itself. See FACTOR MARKET, FACTORING.

factor cost the value of goods and services produced, measured in terms of the cost of the FACTOR INPUT (materials, labour, etc.) used to produce them, that is, excluding any indirect taxes levied on products and any subsidies offered on products. For example, a product costing £10 to produce (including profit) and with a £1 indirect tax levied on it would have a market price of £11 and a factor cost of £10. See FACTORS OF PRODUCTION.

factor endowment the FACTORS OF PRODUCTION that a country has available to produce goods and services. The size and quality of a country’s resource base (natural resources, labour and capital) determine the amount of goods and services it can produce (see GROSS NATIONAL PRODUCT) and the rate at which it can raise living standards over time (see ECONOMIC GROWTH). Differences between countries in terms of the availability and sophistication of their resource inputs provide an incentive for them to engage in INTERNATIONAL TRADE in order to obtain products that they cannot make efficiently for themselves.

factor income see NATIONAL INCOME.

factoring a financial arrangement whereby a specialist finance company (the factor) purchases a firm’s DEBTS for an amount less than the book value of those debts. The factor’s profit derives from the difference between monies collected from the DEBTS purchased and the actual purchase price of those debts. The firm benefits by receiving immediate cash from the factor rather than having to wait until trade debtors eventually pay their debts and avoids the trouble and expense of pursuing tardy debtors. See CREDIT CONTROL.

factor inputs FACTORS OF PRODUCTION (labour, capital, etc.) that are combined to produce OUTPUT of goods and services. See PRODUCTION FUNCTION, COST FUNCTION.

factor market a market in which FACTORS OF PRODUCTION are bought and sold and in which the prices of labour and other FACTOR INPUTS are determined by the interplay of demand and supply forces. See LABOUR MARKET, CAPITAL MARKET, COMMODITY MARKET, DERIVED DEMAND, MARGINAL PHYSICAL PRODUCT, MARGINAL REVENUE PRODUCT, PRICE SYSTEM.

factors of production the resources that are used by firms as FACTOR INPUTS in producing a good or service. There are three main groups of factor inputs: NATURAL RESOURCES, LABOUR and CAPITAL. Factors of production can be combined together in different proportions to produce a given output (see PRODUCTION FUNCTION); it is assumed in the THEORY OF THE FIRM that firms will select that combination of inputs for any given level of output that minimizes the cost of producing that output (see COST FUNCTION). See ENTREPRENEUR, MOBILITY.

Fair Trading Act 1973 an Act that consolidated and extended UK competition law by controlling MONOPOLIES, MERGERS and TAKEOVERS, RESTRICTIVE TRADE AGREEMENTS and RESALE PRICES. The Act established a new regulatory authority, the OFFICE OF FAIR TRADING (OFT) (headed by the Director-General of Fair Trading) with powers to supervise all aspects of COMPETITION POLICY, including the monitoring of changes in market structure, companies’ commercial policies, the registration of restrictive trade agreements, and the referral, where appropriate, of cases for investigation and report by the Monopolies and Mergers Commission and Restrictive Practices Court. The Act also gave the OFT specific responsibilities to oversee other matters affecting consumers’ interests, including weights and measures, trade descriptions and voluntary codes of good practice.

The Act’s provisions relating to monopolies, restrictive trade agreements and resale prices have now been superseded by the COMPETITION ACT 1998. The Office of Fair Trading, however, continues to supervise these situations as well as being responsible for the regulation of mergers and takeovers under the 1973 Act and the referral of cases to the COMPETITION COMMISSION for investigation and report. See CONSUMER PROTECTION.

fallacy of composition an error in economic thinking that often arises when it is assumed that what holds true for an individual or part must also hold true for a group or whole. For example, if a small number of people save more of their income, this might be considered to be a ‘good thing’ because more funds can be made available to finance investment. But if everybody attempts to save more, this will reduce total spending and income and result in a fall in total saving. See PARADOX OF THRIFT.

family expenditure survey an annual UK government survey of households’ expenditure patterns. The survey provides information that is used by the government to select a typical ‘basket’ of goods and services bought by consumers, the prices of which can then be noted in compiling a RETAIL PRICE INDEX.

FDI see FOREIGN DIRECT INVESTMENT.

feasible region see LINEAR PROGRAMMING.

Federal Reserve Bank the CENTRAL BANK of the USA.

fees the payments to professional persons such as lawyers and accountants for performing services on behalf of clients.

fiat currency see FIDUCIARY ISSUE.

fiduciary issue or fiat currency CURRENCY issued by a government that is not matched by government holdings of GOLD or other securities. In the 19th century most currency issues were backed by gold, and people could exchange their BANK NOTES for gold on demand. Nowadays most governments have only minimal holdings of gold and other securities to redeem their currency so most of their currency issues are fiduciary. See MONEY SUPPLY.

FIMBRA (FINANCIAL INTERMEDIARIES, MANAGERS AND BROKERS REGULATORY ASSOCIATION) see SELF-REGULATORY ORGANIZATION.

final income the INCOME received by a household (or person) after allowing for any payment of INCOME TAX and other taxes and the receipt of various TRANSFER PAYMENTS (social security benefits, etc.). Compare ORIGINAL INCOME. See REDISTRIBUTION-OF-INCOME PRINCIPLE OF TAXATION.

final products GOODS and SERVICES that are consumed by end-users, as opposed to INTERMEDIATE PRODUCTS that are used as FACTOR INPUTS in producing other goods and services. Thus, purchases of bread count as part of final demand but not the flour used to make the bread.

The total market value of all final products (which corresponds with total expenditure in the NATIONAL INCOME ACCOUNTS) corresponds with the total VALUE ADDED at each product stage for all products in a particular economy.

Finance Corporation for Industry see INVESTORS IN INDUSTRY.

finance house a financial institution that accepts deposits from savers and specializes in the lending of money by way of INSTALMENT CREDIT (hire purchase loans) and LEASING for private consumption and business investment purposes. See FINANCIAL SYSTEM.

financial accounting the accounting activities undertaken by a company directed towards the preparation of annual PROFIT-AND-LOSS ACCOUNTS and BALANCE SHEETS in order to report to shareholders on their company’s overall (profit) performance. See MANAGEMENT ACCOUNTING.

financial innovation the development by FINANCIAL INSTITUTIONS of new financial products and processes for the transmission of money and the lending and borrowing of funds, for example, telephone banking services, direct debit systems, credit cards, etc. These developments have augmented the traditional means of transmitting money (cash, cheques) and may have served to increase the velocity of circulation of money. They have also increased the availability of CREDIT and, by creating new ‘NEAR MONEY’ assets, have served to extend the liquidity base of the economy. This has tended to make the application of MONETARY POLICY by the authorities more complex.

financial institution an institution that acts primarily as a FINANCIAL INTERMEDIARY in channelling funds from LENDERS to BORROWERS (e.g. COMMERCIAL BANKS, BUILDING SOCIETIES) or from SAVERS to INVESTORS (e.g. PENSION FUNDS, INSURANCE COMPANIES). See FINANCIAL SYSTEM.

Financial Intermediaries, Managers and Brokers Regulatory Association (FIMBRA) a body that was responsible for regulating firms that advise and act on behalf of members of the general public in financial dealings such as life assurance policies, unit trusts, etc. See SELF-REGULATORY ORGANIZATION.

financial intermediary an organization that operates in financial markets, linking LENDERS and BORROWERS or SAVERS and INVESTORS. See FINANCIAL SYSTEM, COMMERCIAL BANK, SAVINGS BANK, BUILDING SOCIETY, PENSION FUND, INSURANCE COMPANY, UNIT TRUST, INVESTMENT TRUST COMPANY, INTERMEDIATION.

financial sector that part of the ECONOMY that is concerned with the transactions of FINANCIAL INSTITUTIONS. Financial institutions provide money transmission services and loan facilities, and influence the workings of the ‘real’ economy by acting as intermediaries in channelling SAVINGS and other funds into INVESTMENT uses. The financial sector, together with the CORPORATE SECTOR and PERSONAL SECTOR, constitute the PRIVATE SECTOR. The private sector, PUBLIC (GOVERNMENT) SECTOR and FOREIGN SECTOR make up the national economy. See FINANCIAL SYSTEM.

financial security a financial instrument issued by companies, financial institutions and the government as a means of borrowing money and raising new capital. The most commonly used financial securities are SHARES, STOCKS, DEBENTURES, BILLS OF EXCHANGE, TREASURY BILLS and BONDS. Once issued, these securities can be bought and sold either on the MONEY MARKET or on the STOCK EXCHANGE. See WARRANT, CERTIFICATE OF DEPOSIT, CONSOLS.

Financial Services Act 1986 (as amended by the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000) a UK Act that provides a regulatory system for the FINANCIAL SECURITIES and INVESTMENT industry. The Act covers the businesses of securities dealing and investment, commodities and financial futures, unit trusts and some insurance (excluding the Lloyds insurance market). Also excluded from its remit is commercial banking, which is supervised by the Bank of England, and mortgage and other business of the building societies, which is regulated separately by the BUILDING SOCIETY ACT 1986.

The main areas covered by the Act are the authorization of securities and investment businesses, and the establishment and enforcement of rules of good and fair business practice. The DEPARTMENT OF TRADE AND INDUSTRY, through its appointed agency, the Financial Services Authority (formerly the Securities and Investment Board), is responsible for the overall administration of the Act, in conjunction with RECOGNIZED INVESTMENT EXCHANGES (RIEs) and RECOGNIZED PROFESSIONAL BODIES (RPBs).

Originally the Act set up five SELF-REGULATORY ORGANIZATIONS (SRO) to regulate firms providing financial securities and investment services: The Securities Association (TSA), Association of Futures Brokers and Dealers (AFBD), Investment Management Regulatory Organization (IMRO), Life Assurance and Unit Trust Regulatory Organization (LAUTRO) and Financial Intermediaries, Managers and Brokers Regulatory Association (FIMBRA). The TSA and AFBD merged in 1991 to form the Securities and Futures Authority (SFA), and in 1994 LAUTRO and FIMBRA merged to form the Personal Investment Authority (PIA). In 2000 the newly established Financial Services Authority took over the responsibilities of the three remaining self-regulatory organizations, thus bringing all aspects of the regulation of the securities and investment industry under ‘one roof’.

The general objective of the legislation is to ensure that only persons deemed to be ‘fit and proper’ are authorized to undertake securities and investment business, and that they conduct their business according to standards laid down by the SROs, RIEs and RPBs, leading, for example, to the clarification of the relationship between the firm and its clients, especially as regards disclosure of fees and charges.

The Financial Services Act also paved the way for important changes in the structure of the personal financial services industry. The Act, together with the Building Societies Act 1986, has enabled financial services providers such as insurance companies and building societies to broaden their portfolio of product offerings to include, for example, personal pensions, unit trusts and individual savings accounts (ISAs), thus increasing competition in the industry by breaking down traditional ‘demarcation’ boundaries in respect of ‘who does what’.

Financial Services Authority (FSA) a body that is responsible for regulating all aspects of the provision of financial securities and investment under the FINANCIAL SERVICES ACT 1986 (as amended by the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000). Previously this task was split between various other organizations, including the Securities and Futures Authority, Personal Investment Authority and the Investment Management Regulatory Organization. See SELF-REGULATORY ORGANIZATION.

financial system a network of financial institutions (BANKS, COMMERCIAL BANKS, BUILDING SOCIETIES, etc.) and markets (MONEY MARKET, STOCK EXCHANGE) dealing in a variety of financial instruments (BANK DEPOSITS, TREASURY BILLS, STOCKS and SHARES, etc.) that are engaged in money transmission and the lending and borrowing of funds.

The financial institutions and markets occupy a key position in the economy as intermediaries in channelling SAVINGS and other funds to BORROWERS. In so doing, one of their principal tasks is to reconcile the different requirements of savers and borrowers, thereby facilitating a higher level of saving and INVESTMENT than would otherwise be the case. Savers, in general, are looking for a safe and relatively risk-free repository for their monies that combines some degree of liquidity (i.e. ready access to their money) with a longer-term investment return that protects the real value of their wealth as well as providing current income. Borrowers, in general, require access to funds of varying amounts to finance current, medium-term and long-term financial and capital commitments, often, as is especially the case with business investments, under conditions of unavoidable uncertainty and high degrees of risk. The financial institutions help to reconcile these different requirements in the following three main ways:

(a) by pooling together the savings of a large number of individuals, so making it possible, in turn, to make single loans running into millions of pounds;

(b) by holding a diversified portfolio of assets and lending for a variety of purposes to gain economies of scale by spreading their risks while still keeping profitability high;

(c) by combining the resources of a large number of savers to provide both for individuals to remove their funds at short notice and for their own deposits to remain stable as a base for long-term lending.

Financial Times All-Share Index see SHARE PRICE INDEX.

fine-tuning a short-run interventionist approach to the economy that uses monetary and fiscal measures to control fluctuations in the level of AGGREGATE DEMAND, with the aim of minimizing deviations from MACROECONOMIC POLICY objectives. The application of fine-tuning, however, is beset with problems of accurately FORECASTING fluctuations in economic activity and in gauging the magnitude and timing of counter-cyclical measures. See DEMAND MANAGEMENT, MONETARY POLICY, FISCAL POLICY.

![]()

firm or company or supplier or enterprise

A transformation unit concerned with converting FACTOR INPUTS into higher-valued intermediate and final GOODS or SERVICES. The firm or BUSINESS is the basic producing/supplying unit and is a vital building block in constructing a theory of the market to explain how firms interact and how their pricing and output decisions influence market supply and price (see THEORY OF THE FIRM, THEORY OF MARKETS).

The legal form of a firm consists of:

(a) a sole proprietorship: a firm owned and controlled (managed) by a single person, i.e. the type of firm that most closely approximates to that of the ‘firm’ in economic theory.

(b) a partnership: a firm owned and controlled by two or more persons who are parties to a partnership agreement.

(c) a JOINT-STOCK COMPANY: a firm that is owned by a group of ordinary shareholders and the capital of which is divided up into a number of SHARES. See COOPERATIVE.

The economic form of a firm consists of:

(a) a horizontal firm: a firm that is engaged in a single productive activity, e.g. motor-car assembly.

(b) a vertical firm: a firm that undertakes two or more vertically linked productive activities, e.g. the production of car components (clutches, steel body shells) and car assembly.

(c) a diversified or conglomerate firm: a firm that is engaged in a number of unrelated productive activities, e.g. car assembly and the production of bread.

For purposes of COMPANY LAW and the application of many company taxes and allowances (e.g. CORPORATION TAX and CAPITAL ALLOWANCES), a distinction is made between ‘small and medium-sized’ companies and ‘large’ companies. Small and medium-sized companies are defined as follows (Companies Act, 1995):

(a) annual turnover of less than £11.2 million;

(b) gross assets of under £5.6 million;

(c) not more than 250 employees.

In 2004 there were some 3,800,000 firms in the UK, of which 70% were run by the self-employed. Most businesses were small, with around 3,766,000 firms employing fewer than 50 people, 27,200 firms employing between 50 and 249 people, while only 6,900 firms employed more than 250 people. In terms of their contribution to GROSS DOMESTIC PRODUCT (GDP), however, firms employing more than 50 people contributed in excess of 75% of total output.

The total stock of firms fluctuates from year to year, depending on the net balance of new start-up businesses and those businesses ceasing trading (see INSOLVENCY). Generally, the total stock of firms increases when the economy is expanding (or as a result of some ‘special’ factor, e.g. the surge in newly established INTERNET businesses) and falls in a recession.

A final point to note is that with the increasing globalization of the world economy, MULTINATIONAL COMPANIES are becoming more prevalent in economics such as the UK’s (see FOREIGN INVESTMENT for further details). See HORIZONTAL INTEGRATION, VERTICAL INTEGRATION, DIVERSIFICATION, BUSINESS CYCLE.

![]()

firm growth the expansion of the size of a FIRM over time. Typical measures of firm growth are the growth of assets or capital employed, turnover, profits and number of employees. Some firms remain small, either by choice or circumstances (e.g. the ‘corner shop’); other firms expand to become large, either in a national or international context (see MULTINATIONAL COMPANY) through either/or ORGANIC GROWTH and EXTERNAL GROWTH (MERGERS, TAKEOVERS and STRATEGIC ALLIANCES). Firms may expand in their original lines of business (HORIZONTAL INTEGRATION), become VERTICALLY INTEGRATED or they may expand into new business activities (DIVERSIFICATION). See PRODUCT MARKET MATRIX.

The process of growth is initiated and facilitated by a combination of managerial, economic, financial and ‘chance’ factors:

(a) Managerial: a typical catalyst underpinning firm growth is an ambitious ENTREPRENEUR, he or she establishing a new firm and setting out to create a ‘big business’. Over time, as a firm expands, the original founder is usually unable to manage all facets of the business and will need the assistance of other directors and professional managers. Edith Penrose developed a ‘managerial theory of firm growth’ based on the idea that once directors/managers are fully on top of running an existing business activity, they develop ‘slack’, which can then be used to extend their time and expertise to running other lines of business. While firms may develop a growth philosophy and impetus, however, serious management ‘mistakes’ may occur in the form of a failure to identify changing customer needs (see, for example, the recent setbacks at the retailing group Marks & Spencer and the car producer Rover), or ill-judged diversifications may reverse growth potential and put the very survival of the firm under threat;

(b) Economic: some firms thrive and grow while others decline or go bankrupt (or are taken over) because the former firms are superior in creating and sustaining COMPETITIVE ADVANTAGES, which enables them to ‘meet and beat’ rival firms (see RESOURCE-BASED THEORY OF THE FIRM). Firms that are able to take full advantage of ECONOMICS OF SCALE and the EXPERIENCE CURVE are able to expand their sales and market shares by producing their products at lower cost and selling them at lower prices than rivals (see SURVIVOR PRINCIPLE); similarly, firms that are able to exploit PRODUCT DIFFERENTIATION advantages, particularly through developing new products, are able to expand at the expense of less innovative rivals. For example, Microsoft has gained a worldwide dominance of software systems through its ‘Windows’ technology, ECONOMIES OF SCOPE are often important in underpinning growth through concentric diversification, where firms ‘transfer’ resources and skills from their core activities into related areas of business;

(c) Financial: as they grow, firms will need to obtain additional financial resources. This may involve the firm in steadily ploughing back profits over the years. A quicker way to fund expansion, however, often involves the firm converting from a ‘sole proprietor’ status to one of public JOINT-STOCK COMPANY (Plc) by floating the business on the STOCK EXCHANGE (see FLOTATION). Plc’s typically continue to finance their expansion by issuing new shares to their existing shareholders (see RIGHTS ISSUE), by increased borrowing from COMMERCIAL BANKS and investors (see CORPORATE BOND) and financing mergers and takeovers by exchanging new shares in the enlarged company for those of target companies;

(d) Chance or luck factors: being in the ‘right place at the right time’ often affects the fortunes of firms. A growth opportunity may occur, for example, through the discovery of a hitherto unknown North Sea oilfield by an oil company such as BP; or from the UK government’s decision to deregulate the telecommunications and bus markets, which have provided growth opportunities for new suppliers to enter these markets such as Vodafone and Stagecoach, respectively. See also LAW OF PROPORTIONATE EFFECT.

The comparative rates of growth achieved by firms determine the eventual number and size distribution of the firms supplying a particular market and thus affects MARKET STRUCTURE. The differential growth of firms provides some justification for the existence of OLIGOPOLY or MONOPOLY, in particular positions of market dominance by the leading firms in a market that is secured through a superior MARKET PERFORMANCE. See MARKET CONCENTRATION.

firm location the area where a firm chooses to locate its business. In principle, a profit-maximizing firm will locate where its production and distribution costs are minimized relative to revenues earned. Often firms are faced with competing pulls of nearness to their market (to reduce product distribution costs) and nearness to their raw material supplies (to reduce materials transport costs), and must seek to balance these costs. Some firms have little choice in this regard, service companies being forced to locate near customers, and mineral extraction companies having to locate near materials’ sources. Many firms are relatively footloose, though, and are free to locate anywhere, influenced by the general attractiveness of an area, the quality of its transport, communications and education infrastructure, and the skills and reputation of its workforce, etc. See INDUSTRIAL LOCATION, LOCATION OF INDUSTRY, REGIONAL POLICY.

firm objectives an element of MARKET CONDUCT that denotes the goals of the firm in supplying GOODS and SERVICES. In the traditional THEORY OF THE FIRM and the THEORY OF MARKETS, in order to facilitate intermarket comparisons of performance, all firms, whether operating under conditions of PERFECT COMPETITION, MONOPOLISTIC COMPETITION, OLIGOPOLY or MONOPOLY, are assumed to be seeking PROFIT MAXIMIZATION. More recent contributions to this body of theory have postulated a number of alternative firm objectives, including SALES-REVENUE MAXIMIZATION and ASSET-GROWTH MAXIMIZATION In these formulations, profits are seen as contributing to the attainment of some other objective rather than as an end in themselves.

Other economists have drawn attention to the fact that the presence of uncertainty and incomplete information in most market situations means that profit maximization, in the way depicted in the theoretical models, is unattainable and that in practice ‘real world’ firms use more pragmatic performance targets to guide their actions.

For example, Philips, the electrical products company (2004), aims to achieve a 20% return on capital employed, while other companies are concerned to enhance shareholder value. In the case of the food and drinks group Cadbury Schweppes (1998–2003): ‘Our primary objective is to grow the value of the business for our shareholders. “Managing for Value” is the business philosophy which unites all our activities in pursuit of this objective. The objective is quantified. We have set three financial targets to measure our progress: 1. To increase our earnings per share by at least 10% every year; 2. To generate £150 million of free cash flow every year; and 3. To double the value of our shareholders’ investment within four years.’

Other companies express their objectives in more general terms, citing the creation of shareholder value as their main aim but also a concern for other STAKEHOLDER interests (employees, customers, the ‘community’ at large (see SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY)). For example, Prudential, the insurance group (2003): ‘Our commitment to the shareholders who own Prudential is to maximize the value over time of their investment. We do this by investing for the long term to develop and bring out the best in our people and our business to produce superior products and services, and hence superior financial returns. Our aim is to deliver top quartile performance among our international peer groups in terms of total shareholder returns. At Pruden-tial our aim is lasting relationships with our customers and policyholders, through products and services that offer value for money and security. We also seek to enhance our company’s reputation, built over 150 years, for integrity and for acting responsibly within society.’ BG, the gas exploration and production company, state (2003): ‘We aim to achieve good returns for our shareholders whilst providing a good service to our customers and contributing to the economies of the countries in which we operate.’

Also instructive are the objectives that are set to trigger awards to company executive directors (i.e. those persons responsible for determining company objectives and policies) under EXECUTIVE STOCK OPTION SCHEMES. For example, Whitbread, the leisure company (2003), requires that the company’s earnings per share growth is greater than the increase in the RETAIL PRICE INDEX by at least 12% over three years. See MANAGERIAL THEORIES OF THE FIRM, DIVORCE OF OWNERSHIP FROM CONTROL, BEHAVIOURAL THEORY OF THE FIRM, SATISFICING THEORY, MANAGEMENT UTILITY MAXIMIZATION, MISSION STATEMENT, CORPORATE GOVERNANCE, LONG-TERM INCENTIVE PLAN, PRINCIPAL-AGENT THEORY.

first-in first-out (FIFO) see STOCK VALUATION.

fiscal drag the restraining effect of PROGRESSIVE TAXATION on economic expansion. As NATIONAL INCOME rises, people move from lower to higher tax brackets, thereby increasing government TAXATION receipts. The increase in taxation constitutes a ‘leakage’ (from the CIRCULAR FLOW OF NATIONAL INCOME) that will reduce the rate of expansion of AGGREGATE DEMAND below that which would otherwise be the case. Governments may choose as part of FISCAL POLICY to adjust for the effects of fiscal drag by regularly increasing personal tax allowances.

Fiscal drag can also serve to automatically constrain the effect of the pressure of INFLATION in the economy, for with a high rate of inflation people will tend to move into higher tax brackets, thereby increasing their total taxation payments, decreasing their disposal income and reducing aggregate demand. This has the effect of reducing the pressure of DEMAND-PULL INFLATION. See AUTOMATIC (BUILT-IN) STABILIZERS.

![]()

fiscal policy

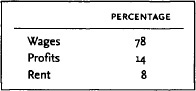

An instrument of DEMAND MANAGEMENT that seeks to influence the level and composition of spending in the economy and thus the level and composition of output (GROSS DOMESTIC PRODUCT). In addition, fiscal policy can affect the SUPPLY-SIDE of the economy by providing incentives to work and investment. The main measures of fiscal policy are TAXATION and GOVERNMENT EXPENDITURE.

The fiscal authorities (principally the TREASURY in the UK) can employ a number of taxation measures to control AGGREGATE DEMAND or spending: DIRECT TAXES on individuals (INCOME TAX) and companies (CORPORATION TAX) can be increased if spending needs to be reduced, for example, to control inflation; i.e. an increase in income tax reduces people’s disposable income, and similarly an increase in corporation tax leaves companies with less profit available to pay dividends and to reinvest. Alternatively, spending can be reduced by increasing INDIRECT TAXES: an increase in VALUE ADDED TAX on products in general, or an increase in EXCISE DUTIES on particular products such as petrol and cigarettes, will, by increasing their price, lead to a reduction in purchasing power.

The government can use changes in its own expenditure to affect spending levels: for example, a cut in current purchases of products or capital investment by the government again serves to reduce total spending in the economy.

Taxation and government expenditure are linked together in terms of the government’s overall fiscal or BUDGET position: total spending in the economy is reduced by the twin effects of increased taxation and expenditure cuts with the government running a budget surplus (see Fig. 18). If the objective is to increase spending, then the government operates a budget deficit, reducing taxation and increasing its expenditure.

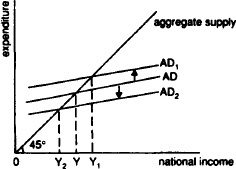

A decrease in government spending and an increase in taxes (a WITHDRAWAL from the CIRCULAR FLOW OF NATIONAL INCOME) reduces aggregate demand and, through the MULTIPLIER process, serves to reduce inflationary pressures when the economy is ‘over-heating’. By contrast, an increase in government spending and/or decrease in taxes (an INJECTION into the circular flow of national income) stimulates aggregate demand and, via the multiplier effect, creates additional jobs to counteract UNEMPLOYMENT. Fig. 70 shows the effect of an increase in government expenditure and/or cuts in taxes in raising aggregate demand from AD to AD1 and national income from Y to Y1, and the effect of a decrease in government expenditure and/or increases in taxes, lowering aggregate demand from AD to AD2 and national income from Y to Y2.

The use of budget deficits was first advocated by KEYNES as a means of counteracting the mass unemployment of the 1920s and 1930s. With the widespread acceptance of Keynesian ideas by Western governments in the period since 1945, fiscal policy was used as the main means of ‘fine-tuning’ the economy to achieve full employment.

In practice, the application of fiscal policy as a short-term stabilization technique encounters a number of problems that reduce its effectiveness. Taxation rate changes, particularly alterations to income tax, are administratively cumbersome to initiate and take time to implement; likewise, a substantial proportion of government expenditure on, for example, schools, roads, hospitals and defence reflects longer-term economic and social commitments and cannot easily be reversed without lengthy political lobbying. Also, changes in taxes or expenditure produce ‘multiplier’ effects (i.e. some initial change in spending is magnified and transmitted around the economy) but to an indeterminate extent. Moreover, the use of fiscal policy to keep the economy operating at high levels of aggregate demand so as to achieve full employment often leads to DEMAND-PULL INFLATION.

Experience of fiscal policy has indicated that the short-termism approach to demand management has not in fact been especially successful in stabilizing the economy. As a result, medium-term management of the economy has assumed a greater degree of significance (see MEDIUM-TERM FINANCIAL STRATEGY). Also, increasingly, fiscal policy has been seen as an important tool in providing work incentives, in particular tackling the problem of ‘voluntary’ unemployment. (See SUPPLY-SIDE and UNEMPLOYMENT entries for further details.)

In the past the authorities have occasionally set ‘targets’ for fiscal policy, most notably ‘caps’ on the size of the PUBLIC SECTOR NET CASH REQUIREMENT (PSNCR). Recently, the government has accepted that fiscal stability is an important element in the fight against inflation. In 1997, the government set an inflation ‘target’ of an increase in the RETAIL PRICE INDEX (RPI) of no more than 2½% per annum and ceded powers to a newly established MONETARY POLICY COMMITTEE to set official interest rates. In December 2003 the RPIX was replaced by the consumer price index and the inflation ‘target’ was reduced to 2%. In doing this, the government explicitly recognized that a low inflation economy was essential in order to achieve another of its priorities – low UNEMPLOYMENT (see EXPECTATIONS-ADJUSTED/AUGMENTED PHILLIPS CURVE). To this end, fiscal ‘prudence’, specifically a current budget deficit within the European Union’s Stability and Growth Pact limits of no more than 3% of GDP (and an outstanding total debt limit of 60% of GDP) was endorsed as a necessary adjunct to avoid excessive monetary creation of the kind that had fuelled previous runaway inflations. In fact, the government has gone further than this in adopting the so-called ‘golden rule’, which requires that the government should ‘aim for an overall budget surplus over the economic cycle (defined as 1998/99 to 2003/04)’, with some of the proceeds being used to pay off government debt to reduce outstanding debt eventually to 40% of GDP. Along the way it has introduced more rigorous standards for approving increases in public spending, in particular the ‘sustainable investment rule’, which stipulates that the government should only borrow to finance capital investment and not to pay for general spending. In addition, the government has determined that it will ‘ring-fence’ increases in particular tax receipts to be used only for funding specific activities. For example, receipts from future increases in fuel taxes and tobacco taxes will be spent, respectively, only on road-building programmes and the National Health Service. See FISCAL STANCE, DEFLATIONARY GAP, INFLATIONARY GAP, KEYNESIAN ECONOMICS, MONETARISM, MONETARY POLICY, BUSINESS CYCLE, PUBLIC FINANCE, BUDGET (GOVERNMENT), CROWDING-OUT EFFECT, STEALTH TAX, INTERNAL-EXTERNAL BALANCE MODEL, I-S/L-M MODEL.

Fig. 70 Fiscal policy. The effect of (a) an increase in government spending/tax cuts (AD1 and (b) a decrease in government spending/tax i ncreases (AD2).

![]()

fiscal stance the government’s underlying position in applying FISCAL POLICY, that is, whether it plans to match its expenditure and taxation revenues (a planned BALANCED BUDGET) or deliberately plans to spend more than it expects to receive in taxation revenues (a planned BUDGET DEFICIT), or deliberately plans to spend less than it receives in taxation revenues (a planned BUDGET SURPLUS). This represents the government’s ‘discretionary’ fiscal policy. Its actual budgetary position, however, can deviate from its fiscal stance insofar as, for example, recession will cause taxable incomes and expenditures to fall below expected levels and unemployment and other social security payments to increase above the expected level. Thus, without any actual change in the government’s fiscal stance and tax rates set, the government’s budget position and borrowing requirements can vary with the level of economic activity. See PUBLIC SECTOR BORROWING REQUIREMENT.

fiscal year the government’s accounting year, which, in the UK, runs from 6 April to 5 April the following year. Different countries frequently have a fiscal year different from the normal calendar year. In the USA, the fiscal year runs up to 30 June. See BUDGET (GOVERNMENT).

Fisher effect an expression that formally allows for the effects of INFLATION upon the INTEREST RATE of a LOAN or BOND. The Fisher equation, devised by Irving Fisher (1867–1947), expresses the nominal interest rate on a loan as the sum of the REAL INTEREST RATE and the rate of inflation expected over the duration of the loan:

R = r + F

where R = nominal interest rate, r = real interest rate and F = rate of annual inflation. For example, if inflation is 6% in one year and the real interest rate required by lenders is 4%, then the nominal interest rate will be 10%. The inflation premium of 6% incorporated in the nominal interest rate serves to compensate lenders for the reduced value of the currency loaned when it is returned by borrowers.

The Fisher effect suggests a direct relationship between inflation and nominal interest rates, changes in annual inflation rates leading to matching changes in nominal interest rates. See INTERNATIONAL FISHER EFFECT.

Fisher equation see QUANTITY THEORY OF MONEY.

five forces model of competition see COMPETITIVE STRATEGY.

five-year plan see NATIONAL PLAN.

fixed assets the ASSETS, such as buildings and machinery, that are bought for long-term use in a firm rather than for resale. Fixed assets are retained in the business for long periods and generally each year a proportion of their original cost will be written off against PROFITS for amortization (see DEPRECIATION 2) to reflect the diminishing value of the asset. In a BALANCE SHEET, fixed assets are usually shown at cost less depreciation charged to date. Certain fixed assets, such as property, tend to appreciate in value (see APPRECIATION 2) and need to be revalued periodically to help keep their BALANCE SHEET values in line with market values. See CURRENT ASSETS, RESERVE.

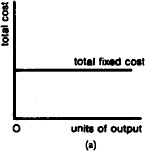

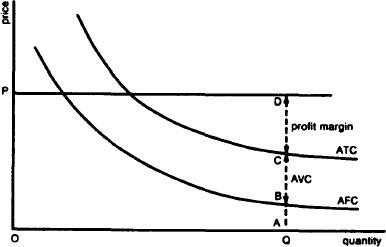

fixed costs any costs that, in the SHORT RUN, do not vary with the level of output of a product. They include such items as rent and depreciation of fixed assets, the total cost of which remains unchanged regardless of changes in the level of activity. Consequently, fixed cost per unit of product will fall as output increases as total fixed costs are spread over a larger output. See Fig. 71.

Fig. 71 Fixed costs. (a) The graph represents payments made for the use of FIXED FACTOR INPUTS (plant and equipment, etc.) which must be met irrespective of whether output is high or low. (b) The graph represents the continuous decline in average fixed cost (AFC) as output rises as a given amount of fixed cost is spread over a greater number of units.

In the THEORY OF MARKETS, a firm will leave a product market if in the LONG RUN it cannot earn sufficient TOTAL REVENUE to cover both total fixed costs and total VARIABLE COSTS. However, it will remain in a market in the short run as long as it can generate sufficient total revenue to cover total variable costs and make some CONTRIBUTION towards total fixed costs, even though it is still making a loss, on the assumption that this loss-making situation is merely a temporary one. See MARKET EXIT.

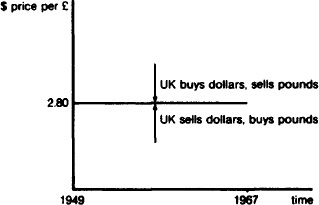

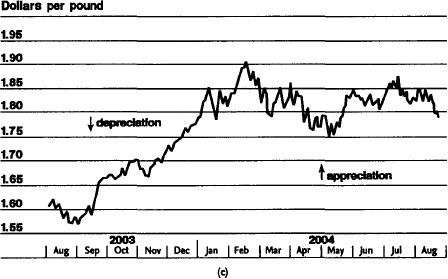

fixed exchange-rate system a mechanism for synchronizing and coordinating the EXCHANGE RATES of participating countries’ CURRENCIES. Under this system, currencies are assigned a central fixed par value in terms of the other currencies in the system and countries are committed to maintaining this value by support-buying and selling. For example, between 1949 and 1967, under the INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND’S former fixed exchange rate system, the UK maintained a rate of exchange at £1 = $2.80 with the US dollar (see Fig. 72). If the price of the £ rose (appreciated) in the FOREIGN EXCHANGE MARKETS, the UK CENTRAL BANK bought dollars and sold pounds; if the price of the £ fell (depreciated), the central bank sold dollars and bought pounds. Because of the technical difficulties of hitting the central rate with complete accuracy on a day-to-day basis, most fixed exchange rate systems operate with a ‘band of tolerance’ around the central rate: for example, the former EUROPEAN MONETARY SYSTEM allowed members’ currencies to fluctuate 2.25% either side of the central par value. See ECONOMIC AND MONETARY UNION.

Once an exchange rate is fixed, countries are expected to maintain this rate for fairly lengthy periods of time but are allowed to devalue their currencies (that is, refix the exchange rate at a new, lower value; see DEVALUATION) or revalue it (refix it at a new, higher value; see REVALUATION) if their BALANCE OF PAYMENTS are, respectively, in chronic deficit or surplus. See DEPRECIATION 1 for details of the back-up factors that are critical to the ‘success’ of exchange rate changes in removing payments disequilibriums.

Fig. 72 Fixed exchange-rate system. The exchange rate between the pound and the dollar between 1949 and 1967.

Generally speaking, the business and financial communities prefer relatively fixed exchange rates to FLOATING EXCHANGE RATES, since it enables them to enter into trade (EXPORT, IMPORT contracts) and financial transactions (FOREIGN INVESTMENT) at known foreign exchange prices so that the profit and loss implications of these deals can be calculated in advance. The chief disadvantage with such a system is that governments often tend to delay altering the exchange rate, either because of political factors (e.g. the ‘bad publicity’ surrounding devaluations) or because they may choose to deal with the balance of payments difficulties by using other measures, so that the pegged rate gets seriously out of line with underlying market tendencies. When this happens, SPECULATION against the currency tends to build up, leading to highly disruptive HOT MONEY flows that destabilize currency markets and force the central bank to spend large amounts of its INTERNATIONAL RESERVES to defend the parity. If one currency is ‘forced’ to devalue under such pressure, this tends to produce a ‘domino’ effect as other weak currencies are likewise subjected to speculative pressure.

Proponents of fixed exchange rate systems (particularly relatively small-group blocs such as the former European Monetary System) emphasize that in order to reduce ‘internal’ tensions between participants, economically stronger members should play their full part in the adjustment process (for example, revaluing their currencies when appropriate) rather than leaving weaker members to shoulder the entire burden, and countries should aim for a broad ‘convergence’ in their economic policies, both with respect to objectives (e.g. low inflation rate) and instruments (e.g. similar interest rate structures). See BALANCE OF PAYMENTS EQUILIBRIUM, ADJUSTMENT MECHANISM, ADJUSTABLE PEG EXCHANGE-RATE SYSTEM, CRAWLING-PEG EXCHANGE-RATE SYSTEM, GOLD STANDARD, FOREIGN EXCHANGE EQUALIZATION ACCOUNT, EURO.

fixed factor input a FACTOR INPUT to the production process that cannot be increased or reduced in the SHORT RUN. This applies particularly to capital inputs such as (given) plant and equipment. See VARIABLE FACTOR INPUT, RETURNS TO THE VARIABLE FACTOR INPUT, FIXED COSTS.

fixed-interest financial securities any FINANCIAL SECURITIES that have a predetermined fixed INTEREST RATE attached to their PAR VALUE, for example, TREASURY BILLS, DEBENTURES and PREFERENCE SHARES. Debentures with a par value of £100 at 5% will pay out a fixed rate of interest of £5 per annum until the expiry of the debenture, that is, the date of redemption. See BONDS.

fixed investment any INVESTMENT in plant, machinery, equipment and other durable CAPITAL GOODS. Fixed investment in the provision of social products like roads, hospitals and schools is undertaken by central and local government as part of government expenditure. Fixed investment in plant, equipment and machinery in the private sector will be influenced by the expected returns on such investments and the cost of capital needed to finance planned investments.

Investment is a component of AGGREGATE DEMAND and so affects the level of economic activity in the short run, while fixed investment serves to add to the economic INFRASTRUCTURE and raises POTENTIAL GROSS NATIONAL PRODUCT over the longer term.

In the short run, expected returns from an investment in plant will depend upon business confidence about sales prospects and therefore plant utilization. The volatility of business EXPECTATIONS means that planned levels of investment can vary significantly over time, leading to large changes in the demand for capital goods (see ACCELERATOR), i.e. large fluctuations in the investment component of aggregate demand leading to larger fluctuations in output and employment through the MULTIPLIER effect. See BUSINESS CYCLE, INVENTORY INVESTMENT, MARGINAL EFFICIENCY OF CAPITAL/INVESTMENT.

fixed targets an approach to macroeconomic policy that sets specific target values in respect of the objectives of FULL EMPLOYMENT, PRICE STABILITY, ECONOMIC GROWTH and BALANCE OF PAYMENTS EQUILIBRIUM:

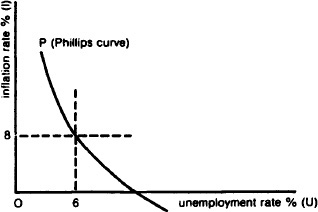

The essence of this approach can be illustrated, to simplify matters, by reference to the PHILLIPS CURVE ‘trade-off’ between unemployment and inflation illustrated in Fig. 73. See MACROECONOMIC POLICY, OPTIMIZING.

Fig. 73 Fixed targets. The Phillips curve shows that as unemployment (U) falls, inflation (I) increases, and vice-versa. The Phillips curve is drawn as P. Ideally, the authorities would like the economy to be at the origin, point O, for here full employment and complete price stability are simultaneously attained. The Phillips curve, however, sets a limit to the combinations of U and I which can be achieved in practice. Given this constraint, the task of the authorities is to specify ‘acceptable’ target values for the two objectives. They could, for example, set a fixed target value on unemployment at 6% and a target value for inflation at 8%, or, alternatively, a lower value for I and a higher value for U.

flag of convenience the grant of a shipping ‘flag’ by a country to a non-national vessel owner. Flags of convenience are usually issued by countries not noted for their participation in international treaties governing shipping rights, and while the ‘flag’ establishes the legal credentials of the ship it often acts as a cloak for illegal activities (e.g. catching fish in unauthorized waters).

flat yield see YIELD.

flexible exchange rate see FLOATING EXCHANGE RATE.

flexible manufacturing system (FMS) a means of PRODUCTION that makes extensive use of ‘programmed’ AUTOMATION and COMPUTERS to achieve rapid production of small batches of components or products while maintaining flexibility in manufacturing a wide range of these items.

Flexible manufacturing systems enable small batches of a product to be produced at the same unit cost as would be achievable with large-scale production, thus diminishing the cost advantages associated with ECONOMIES OF SCALE and lowering the MINIMUM EFFICIENT SCALE. This enables small firms to compete in cost terms with large firms and may lead to a lowering of SELLER CONCENTRATION. See BARRIERS TO ENTRY.

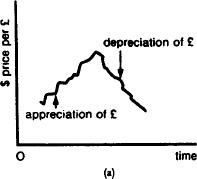

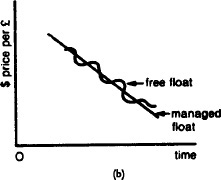

floating exchange-rate system a mechanism for coordinating EXCHANGE RATES between countries’ CURRENCIES that involves the value of each country’s currency in terms of other currencies being determined by the forces of the demand for, and supply of, currencies in the FOREIGN EXCHANGE MARKET. Over time, the exchange rate of a particular currency may rise (APPRECIATION) or fall (DEPRECIATION) depending, respectively, on the strength or weakness of the country’s underlying BALANCE OF PAYMENTS position and exposure to speculative activity (see SPECULATOR), as shown in Fig. 74 (a) and Fig. 74 (b), with their CENTRAL BANKS buying and selling currencies, as appropriate, in the foreign exchange market.

Fig. 74 Floating exchange-rate system. (a) If the UK’s Imports from the USA rise faster than the UK’s exports to the USA, then, in currency terms, the UK’s demand for dollars will increase relative to the demand in the USA for pounds. This will cause the pound to fall (see DEPRECIATION 1) against the dollar, making imports from the USA to the UK more expensive and exports from the UK to the USA cheaper. By contrast, if the UK’s imports from the USA rise more slowly than its exports to the USA, then, in currency terms, its demand for dollars will be relatively smaller than the US demand for pounds. This will cause the pound to rise (see APPRECIATION 1), making imports from the USA to the UK cheaper and exports from the UK to the USA more expensive. (b) The graph shows how nations can manage the float by intervening in the currency market to buy and sell currencies, using their national currency reserves to moderate the degree of short-term fluctuation and smooth out the long-term trend line, (c) UK £-US $ exchange rate.

While this creates a more settled and controlled environment in which to operate, nonetheless firms are usually forced to cover their currency requirements by, for example, taking out OPTIONS in the FUTURES MARKET (see EXCHANGE RATE EXPOSURE).

Moreover, a country’s intervention in currency markets sometimes goes beyond merely ‘smoothing’ its exchange rate and may involve a deliberate attempt to ‘manipulate’ the exchange rate so as to gain a trading advantage over other countries (a so-called ‘dirty float’). See DEPRECIATION 1 entry for details of the back-up factors that are critical to the ‘success’ of exchange-rate changes in removing payments disequilibriums. Compare FIXED EXCHANGE RATE SYSTEM. See PURCHASING POWER PARITY THEORY, ASSET VALUE THEORY, ADJUSTMENT MECHANISM, INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND, FOREIGN EXCHANGE EQUALIZATION ACCOUNT.

flotation the issue of shares in a newly established or existing private company whereby the company goes ‘public’ and obtains a listing of its shares on the STOCK EXCHANGE. See SHARE ISSUE.

flow a measurement of quantity over a specified period of time. Unlike a STOCK, which is not a function of time, a flow measures quantity passing per minute, hour, day or whatever. A common analogy is to a reservoir. The water entering and leaving the reservoir is a flow but the water actually in the reservoir at any one point in time is a stock. INCOME is a flow but WEALTH is a stock.

f.o.b. abbrev. for free-on-board. In BALANCE OF PAYMENTS terms, f.o.b. means that only the basic prices of imports and exports of goods (plus loading charges) are counted while the ‘cost-insurance-freight’ (c.i.f.) charges incurred in transporting the goods from one country to another are excluded.

focus a term used to describe a firm’s concentration on a single or limited range of business activities. By focusing on a ‘core activity’, the firm is better able to reap the benefits of SPECIALIZATION and access ECONOMIES OF SCALE, increase its MARKET SHARE and concentrate management’s attention and capabilities on ‘what they know best’. On the debit side, however, over-specialization may make the firm vulnerable to cyclical and secular downturns in demand while limiting opportunities for achieving long-run growth. See HORIZONTAL INTEGRATION, DIVERSIFICATION.

focus competitive strategy see COMPETITIVE STRATEGY.

Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) an international agency of the UNITED NATIONS, established in 1945. Its primary objective is to improve agricultural productivity and hence the nutritional standards of agrarian countries throughout the world. It achieves this objective through undertaking research on all aspects of farming, fishing and forestry, and by offering technical assistance to those countries that require it. In addition, the FAO continually surveys world agricultural conditions, collects and issues statistics on human nutritional requirements and statistics on farming, fishing, forestry and related topics. See AGRICULTURAL POLICY.

forced saving or involuntary saving the enforced reduction of CONSUMPTION in an economy. This can be achieved directly by the government increasing TAXATION so that consumers’ DISPOSABLE INCOME is reduced or it may occur indirectly as a consequence of INFLATION, which increases the price of goods and services at a faster rate than consumers’ money incomes increase.

Governments may deliberately increase taxes so as to secure a higher level of forced SAVING in order to obtain additional resources for INVESTMENT in the public sector. A ‘forced saving’ policy is often attractive for a DEVELOPING COUNTRY the ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT of which is being held back by a shortage of savings.

![]()

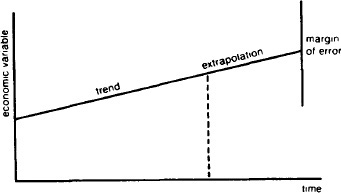

forecasting

The process of making predictions about future general economic and market conditions as a basis for decision-making by government and business. Various forecasting methods can be used to estimate future economic conditions, varying greatly in terms of their subjectivity, sophistication, data requirements and cost:

(a) survey techniques, involving the use of interviews or mailed questionnaires asking consumers or industrial buyers about their future (buying) intentions. Alternatively, members of the sales force may provide estimates of future market sales, or industry experts can offer scenario-type forecasts about future market developments.

(b) experimental methods, providing demand forecasts for new products, etc., based on either the buying responses of small samples of panel consumers or large samples in test markets.

(c) EXTRAPOLATION methods, employing TIME-SERIES ANALYSIS, using past economic data to predict future economic trends. These methods implicitly assume that the historical relationships that have held in the past will continue to hold in the future, without examining causal relationships between the variables involved. Time-series data usually comprise: a long-run secular trend, with certain medium-term cyclical fluctuations; and short-term seasonal variations, affected by irregular, random influences. Techniques such as moving averages or exponential smoothing can be used to analyse and project such time series, though they are generally unable to predict sharp upturns or downturns in economic variables.

(d) Barometric forecasts to predict the future value of economic variables from the present values of particular statistical indicators which have a consistent relationship with these economic variables. Such LEADING INDICATORS as business capital investment plans and new house-building starts can be used as a barometer for forecasting values like economic activity levels or product demand, and they can be useful for predicting sharp changes in these values.

(e) INPUT-OUTPUT methods using input-output tables to show interrelationships between industries and to analyse how changes in demand conditions in one industry will be affected by changes in demand and supply conditions in other industries related to it. For example, car component manufacturers will need to estimate the future demand for cars and the future production plans of motorcar manufacturers who are their major customers.

(f) ECONOMETRIC methods predicting future values of economic variables by examining other variables that are causally related to it. Econometric models link variables in the form of equations that can be estimated statistically and then used as a basis for forecasting. Judgement has to be exercised in identifying the INDEPENDENT VARIABLES that causally affect the DEPENDENT VARIABLE to be forecast. For example, in order to predict future quantity of a product demanded (Qd), we would formulate an equation linking it to product price (P) and disposable income (Y):

Qd = a + bP + cY

then use past data to estimate the regression coefficients d, b and c (see REGRESSION ANALYSIS). Econometric models may consist of just one equation like this, but often in complex economic situations the independent variables in one equation are themselves influenced by other variables, so that many equations may be necessary to represent all the causal relationships involved. For example, the macroeconomic forecasting model used by the British Treasury to predict future economic activity levels has over 600 equations.

Fig. 75 Forecasting. The margin of error expected in economic forecasts.

No forecasting method will generate completely accurate predictions, so when making any forecast we must allow for a margin of error in that forecast. In the situation illustrated in Fig. 75, we cannot make a precise estimate of the future value of an economic variable; rather, we must allow that there is a range of possible future outcomes centred on the forecast value, showing a range of values with their associated probability distribution. Consequently, forecasters need to exercise judgement in predicting future economic conditions, both in choosing which forecasting methods to use and in combining information from different forecasts.

![]()

foreclosure the refusal by a VERTICALLY INTEGRATED firm to supply inputs to non-integrated rivals, or distribute their products, as a means of putting them at a competitive disadvantage. In market situations where there are a substantial number of alternative independent supply sources and outlets, rival suppliers are unlikely to be inconvenienced. However, the control by a DOMINANT FIRM of the majority of input sources and outlets, combined with limitations on the establishment of new ones, could have serious anti-competitive consequences. Under UK COMPETITION POLICY, cases of vertical integration may be referred to the COMPETITION COMMISSION for investigation. See REFUSAL TO SUPPLY.

foreign currency or foreign exchange the CURRENCY of an overseas country that is purchased by a particular country in exchange for its own currency. This foreign currency is then used to finance INTERNATIONAL TRADE and FOREIGN INVESTMENT between the two countries. See FOREIGN EXCHANGE MARKET, FOREIGN EXCHANGE CONTROLS.

foreign direct investment (FDI) investment by a MULTINATIONAL COMPANY in establishing production, distribution or marketing facilities abroad. Sometimes foreign direct investment takes the form of GREENFIELD INVESTMENT, with new factories, warehouses or offices being constructed overseas and new staff recruited. Alternatively, foreign direct investment can take the form of TAKEOVERS and MERGERS with other companies located abroad. Foreign direct investment differs from overseas portfolio investment by financial institutions, which generally involves the purchase of small shareholdings in a large number of foreign companies. See FOREIGN INVESTMENT for further discussion. See HOST COUNTRY, SOURCE COUNTRY, INVEST UK.

foreign exchange see FOREIGN CURRENCY.

foreign exchange controls restrictions on the availability of FOREIGN CURRENCIES by a country’s CENTRAL BANK to assist in the removal of a BALANCE OF PAYMENTS deficit and to control disruptive short-run capital flows (HOT MONEY) that tend to destabilize the country’s EXCHANGE RATES. Where importers can only purchase foreign currencies from the country’s central bank (via their commercial banks) in order to buy products from overseas suppliers, by cutting off the supply of foreign currencies the authorities can reduce the amount of IMPORTS to a level compatible with the foreign currency earned by the country’s EXPORTS. Exchange controls may be applied not only to limit the total amount of currency available but can also be used to discriminate against particular types of imports, thus serving as a form of PROTECTIONISM. See FOREIGN EXCHANGE MARKET.

Foreign Exchange Equalization Account FOREIGN CURRENCIES held by a country’s CENTRAL BANK (for example, the Bank of England) that are used to intervene in the FOREIGN EXCHANGE MARKET in order to stabilize the EXCHANGE RATE of that country’s currency. See FIXED EXCHANGE RATE SYSTEM, EUROPEAN MONETARY SYSTEM, INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND.

foreign exchange market a MARKET engaged in the buying and selling of FOREIGN CURRENCIES. Such a market is required because each country involved in INTERNATIONAL TRADE and FOREIGN INVESTMENT has its own domestic currency, and this needs to be exchanged for other currencies in order to finance trade and capital transactions. This function is undertaken by a network of private foreign exchange dealers and a country’s monetary authorities acting through its central banks.

The foreign exchange market, by its very nature, is multinational in scope. The leading centres for foreign exchange dealings are London, New York and Tokyo.

Foreign currencies can be transacted on a ‘spot’ basis for immediate delivery (see SPOT MARKET) or can be bought and sold for future delivery (see FUTURES MARKET). Some two-thirds of London’s foreign exchange dealings in 2004 were spot transactions.

The foreign exchange market may be left unregulated by governments, with EXCHANGE RATES between currencies being determined by the free interplay of the forces of demand and supply (see FLOATING EXCHANGE RATE SYSTEM), or they may be subjected to support-buying and selling by countries’ CENTRAL BANKS in order to fix them at particular rates. See FIXED EXCHANGE RATE SYSTEM, TOBIN TAX.

foreign exchange reserves see INTERNATIONAL RESERVES.

foreign investment the INVESTMENT by a country’s domestic citizens and businesses and the government in the purchase of overseas FINANCIAL SECURITIES and physical assets – FOREIGN DIRECT INVESTMENT (FDI). Foreign investment in financial assets (PORTFOLIO investment), in particular by institutional investors such as unit trusts and pension funds, is undertaken primarily to diversify risk and to obtain higher returns than would be achieved on comparable domestic investments. Foreign direct investment in new manufacturing plants and sales subsidiaries (GREENFIELD INVESTMENT) or the acquisition of established overseas businesses is undertaken by MULTINATIONAL COMPANIES (MNCS). See CAPITAL MOVEMENT.

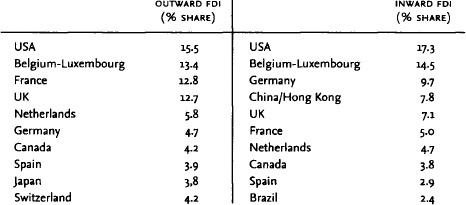

Fig. 76 Foreign investments. Outward and inward FDI flows by leading countries, 2000–03. Source: Balance of Payment Statistics, IMF 2004.

International investment has long complemented INTERNATIONAL TRADE as a resource allocation and transfer mechanism, but in recent decades it has become significantly more important with the expansion of MNCs. A multinational company is a business incorporated in one country (the home or source country) that owns income-generating assets – plants, offices, etc. – in some other country or countries (host countries). The propensity of many MNCs to use a combination of importing/exporting, strategic alliances with foreign partners and wholly owned FDI to source inputs for their operations and to produce and market their products has led to a more complex pattern of world trade and investment. Thus, for example, some international trade flows involving arm’s-length exporting and importing between different firms have been ‘INTERNALIZED’ and are now conducted through intra-subsidiary transfers within a vertically integrated MNC. In some cases exporting to a particular market by a MNC has been replaced by the establishment of a local production plant to meet that demand locally; in other cases trade has been expanded by the establishment of a foreign plant that is then used as an export base to supply adjacent markets. Thus, trade and investment relations between countries need to be looked at as an interrelated, dynamic process rather than an either/or situation (see FOREIGN MARKET SERVICING STRATEGY).

FDI by firms is undertaken to achieve COMPETITIVE ADVANTAGES – lower costs and prices, improved marketing reach and effectiveness (see FOREIGN MARKET SERVICING STRATEGY). In addition to these microeconomic considerations, the macroeconomic effects on the domestic economy can be substantial. Inward investment by foreign-owned companies can ‘top up’ an inadequate level of domestic savings and investment, create new jobs and, through ‘technology transfer’, serve to upgrade the country’s economic capabilities by introducing new industrial processes and products and imparting new skills and practices. On the debit side, fears are often raised relating to the loss of national sovereignty if foreign companies come to dominate key domestic industries and the damaging effects of a reversal of foreign capital inflows. This said, the impact of FDI inflows on the UK economy, for example, has been considerable. In 2003/04 foreign-owned companies accounted for under 1% of all manufacturing firms, but because of the typical large-scale nature of their operations, they accounted for 17% of the UK labour force, 26% of total UK output and 33% of total UK investment. (Source: Business Monitor, PA1002, 2005).

In addition to the effects of FDI on the ‘real’ economy, there is also a financial effect on a country’s BALANCE OF PAYMENTS. The initial ‘one-off’ outflow/inflow of foreign exchange required to pay for the investment shows up as a capital account transaction, while subsequent annual income flows in the form of profits, dividends and interest appear as receipts or debits in the ‘invisibles’ component of the current account.

Over the three-year period 2000–03, FDI flows totalled US $2.6 billion.

Fig. 76 lists the leading countries in outward FDI flows and the leading countries in inward FDI flows for 2000–03. It will be noted that the UK is a major overseas investor and the leading European country for inward investment. See INVEST UK.

foreign market servicing strategy the choice of EXPORTING, LICENSING, using STRATEGIC ALLIANCES (including JOINT VENTURES) or FOREIGN DIRECT INVESTMENT (FDI), or some combination of each, by a MULTINATIONAL COMPANY (MNC) as a means of selling its products in overseas markets. Exporting involves production in one or more locations for sale overseas in target markets; licensing involves the assignment of production and selling rights by an MNC to producers in the target market; strategic alliances involve the combining together on a contractual or equity basis of the resources and skills of two firms; foreign direct investment involves the establishment of the firm’s own production (and selling) facilities in the target market. In resource terms, exporting from established production plants is a relatively inexpensive way of servicing a foreign market, but the firm could be put at a competitive disadvantage either because of local producers’ lower cost structures and control of local distribution channels or because of governmental TARIFFS, QUOTAS, etc., and other restrictions on IMPORTS. Licensing enables a firm to gain a rapid penetration of world markets and can be advantageous to a firm lacking the financial resources to set up overseas operations or where, again, local firms control distribution channels, but the royalties obtained may represent a poor return for the technology transferred. Strategic alliances can enable complementary resources and skills to be combined, enabling firms to supply products in a more cost-effective way and to increase market penetration. Foreign direct investment can be expensive and risky (although HOST COUNTRIES often offer subsidies, etc., to attract such inward investment), but in many cases the ‘presence’ effects of operating locally (familiarity with local market conditions and the cultivation of contacts with local suppliers, distributors and retailers) are important factors in building market share over the long run.

MNCs in practice tend to use various combinations of these modes to service global markets because of the added flexibility it gives to their operations. For example, if governments choose to act on imports by raising tariffs, etc., a MNC may substitute in-market FDI for direct exporting. See FOREIGN INVESTMENT, SCREWDRIVER OPERATION, LOCAL CONTENT RULE.

foreign sector that part of the ECONOMY concerned with transactions with overseas countries. The foreign sector includes IMPORTS and EXPORTS of goods and services as well as CAPITAL MOVEMENTS in connection with investment and banking transactions. The net balance of foreign transactions influences the level and composition of domestic economic activity and the state of the country’s BALANCE OF PAYMENTS. The foreign sector, together with the PERSONAL SECTOR, CORPORATION SECTOR, FINANCIAL SECTOR, PUBLIC (GOVERNMENT) SECTOR, make up the national economy. See also CIRCULAR FLOW OF NATIONAL INCOME.

foreign trade multiplier the increase in a country’s foreign trade resulting from an expansion of domestic demand. The increase in domestic demand has a twofold effect. As well as directly increasing the demand for domestic products, it will also:

(a) directly increase the demand for IMPORTS by an amount determined by the country’s MARGINAL PROPENSITY TO IMPORT;

(b) indirectly it may also increase overseas demand for the country’s EXPORTS by those countries the incomes of which have now been increased by being able to export more to the country concerned.

The latter effect, however, is usually much less than the former so that the overall effect is to ‘dampen down’ the value of the domestic MULTIPLIER; i.e. the increase in net imports serves to partially offset the extra income created by increased spending on domestic products. See CIRCULAR FLOW OF NATIONAL INCOME MODEL, LOCOMOTIVE PRINCIPLE.

forex abbrev. for foreign exchange. See FOREIGN CURRENCY, FOREIGN CURRENCY MARKET.

forfaiting the provision of finance by one firm (the forfaiter) to another firm (the client) by purchasing goods that the client has pre-sold to a customer but for which he has not yet been paid. The forfaiter (which often is a subsidiary of a commercial bank or a specialist firm) buys the client’s goods at a discounted cash price, thus releasing ready money for the client to use to finance his WORKING CAPITAL requirements. The forfaiter then arranges to collect the payment when due from the customer to whom the goods have been sold, thus also saving the client the paperwork involved.

forward contract see FUTURES MARKET.

forward exchange market see FUTURES MARKET.

forward integration the joining together in one FIRM of two or more successive stages in a vertically related production/distribution process; for example, flour millers acquiring their own outlets for flour, such as bakeries. The main motives for forward integration by a firm are to secure the market for the firm’s output and to obtain cost savings. See VERTICAL INTEGRATION, BACKWARD INTEGRATION.

fractional banking a BANKING SYSTEM in which banks maintain a minimum RESERVE ASSET RATIO in order to ensure that they have adequate liquidity to meet customers’ cash demands. See COMMERCIAL BANK.

franchise the assignment by one FIRM to another firm (exclusive franchise) or others (nonexclusive franchise) of the right(s) to supply its product. A franchise is a contractual arrangement (see CONTRACT) that is entered into for a specified period of time, with the franchisee paying a ROYALTY to the franchisor for the rights assigned. Examples of franchises include the Kentucky Fried Chicken and MacDonald’s burger diner and ‘take-away’ chains. Individual franchisees are usually required to put up a large capital stake, with the franchisor providing back-up technical assistance, specialized equipment and advertising and promotion. Franchises allow the franchisor to develop business without having to raise large amounts of capital.

freedom of entry see CONDITION OF ENTRY.

free enterprise economy see PRIVATE ENTERPRISE ECONOMY.

free goods goods such as air and water that are abundant and thus not regarded as scarce economic goods. Such goods will be consumed in large quantities because they have a zero supply price, and there is thus a tendency to overuse these goods, causing environmental POLLUTION.

freehold property a property that is legally owned outright by a person or firm. Compare LEASEHOLD PROPERTY.

free market economy see PRIVATE ENTERPRISE ECONOMY.

free port see FREE TRADE ZONE.

free rider a CONSUMER who deliberately understates his or her preference for a COLLECTIVE PRODUCT in the hope of being able to consume the product without having to pay the full economic price for it.

For example, where a number of householders seek to resurface their common private road, an individual householder might deliberately understate the value of the resurfaced road to himself on the grounds that the other householders will pay to have all the road resurfaced anyhow and that he will therefore enjoy the benefit of it without having to pay towards its resurfacing. See CLUB PRINCIPAL.

free trade the INTERNATIONAL TRADE that takes place without barriers, such as TARIFFS, QUOTAS and FOREIGN EXCHANGE CONTROLS, being placed on the free movement of goods and services between countries. The aim of free trade is to secure the benefits of international SPECIALIZATION. Free trade as a policy objective of the international community has been fostered both generally by the WORLD TRADE ORGANIZATION and on a more limited regional basis by the establishment of various FREE TRADE AREAS, CUSTOM UNIONS and COMMON MARKETS. See GAINS FROM TRADE, EUROPEAN UNION, EUROPEAN FREE TRADE ASSOCIATION, TRADE INTEGRATION.

free trade area a form of TRADE INTEGRATION between a number of countries in which members eliminate all trade barriers (TARIFFS, etc.) among themselves on goods and services but each continues to operate its own particular barriers against trade with the rest of the world. The aim of a free trade area is to secure the benefits of international SPECIALIZATION and INTERNATIONAL TRADE, thereby improving members’ real living standards. The EUROPEAN FREE TRADE ASSOCIATION (EFTA) is one example of a free trade area. See GAINS FROM TRADE, NORTH AMERICAN FREE TRADE AGREEMENT, MERCOSUR, ASIAN PACIFIC ECONOMIC COOPERATION, ASSOCIATION OF SOUTHEAST ASIAN NATIONS.

free trade zone or freeport a designated area within the immediate hinterland of an air or shipping port into which IMPORTS are allowed without payment of IMPORT DUTY (TARIFFS), provided the goods are to be subsequently exported (see EXPORTS) either in their original form or as intermediate products within a final good. See ENTREPOT TRADE.

freight or cargo goods that are in the process of being physically transported from a factory or depot to a customer by road, rail, sea or air, involving both domestically and internationally traded goods. The movement of goods may be done by the supplier’s own distribution division or by independent fleet operators and FREIGHT FORWARDERS. See C. I. F., F. O. B.

freight forwarder or forwarding agent a firm that specializes in the physical movement of goods in transit, arranging the collection of goods from factory, depot, etc., and delivering them direct to the customer in the case of domestic consignments and to seaports, airports, etc., in the case of exported goods. In the latter case, the forwarder also handles the documentation required by the customs authorities and booking arrangements.

frictional unemployment or transitional unemployment UNEMPLOYMENT associated with people changing jobs. In some cases people who leave one job may start another job the next day. In other cases, people may be temporarily unemployed between jobs while they explore possible job opportunities. The latter case constitutes ‘frictional’ unemployment insofar as labour markets do not operate immediately in matching the supply of, and demand for, labour. Some frictional unemployment may be regarded as ‘voluntary’ because people choose to leave their current jobs to look for better ones whereas other frictional unemployment is ‘involuntary’ where people have been dismissed from their current jobs and are forced to look for alternative ones. See JOB CENTRE.

Friedman, Milton (1912–) an American economist who advocates the virtues of the free market system and the need to minimize government regulations of markets in his book, Capitalism and Freedom (1962).

Friedman has attacked Keynesian policies of government fine-tuning of AGGREGATE DEMAND, arguing that such policies accentuate business uncertainty and can destabilize the economy. Instead, he suggests that governments should gradually expand the MONEY SUPPLY at a rate equal to the long-run increase in national output in order to eliminate inflationary tendencies in the economy. In an economy experiencing a high inflation rate, Friedman acknowledges that a sharp reduction in the rate of growth of money supply would deflate demand and cause unemployment to rise. He argues, however, that such a rise in unemployment would be temporary, for once people lower their expectations about future inflation rates, full employment can be restored. Friedman’s monetarist ideas had considerable influence among governments in the 1980s.

Friedman also looked at the relationship between consumption and income, rejecting the Keynesian idea that as peoples’ incomes rise they will spend a smaller proportion of them and save a larger share. Instead, he argued that consumption is a constant fraction of the consumer’s PERMANENT INCOME and that as long-term income rises the proportion of it spent remains the same. See MONETARISM.

friendly society an association of individuals (members) who make regular voluntary contributions into a fund upon which they can draw in times of need or to provide themselves with houses. Friendly societies were the forerunners of the modern INSURANCE SOCIETIES and BUILDING SOCIETIES. See REGISTRAR OF FRIENDLY SOCIETIES, BUILDING SOCIETIES ACT 1986.

fringe benefits any additional benefits offered to employees, such as the use of a company car, free meals or luncheon vouchers, interest-free or low-interest loans, private health care subscriptions, subsidized holidays and share purchase schemes. In the case of senior managers, such benefits or perquisites (perks) can be quite substantial in relation to wages and salaries. Companies offer fringe benefits to attract employees and because such benefits provide a low-tax or no-tax means of rewarding employees compared with normally taxed salaries.