A sea butterfly flutters past. Its spiralling shell is translucent and colourless as though it were sculpted from glass. Inside, I see a cluster of cells twitching and contracting as its heart beats. Little wings stick out from the shell’s flared opening and flicker in energetic bursts, propelling it through the water in circles. It stops now and then as if to catch its breath, and I hold my own as I quietly watch, partly so as not to disturb it but also because this is the first sea butterfly I’ve seen and I can’t quite believe my eyes.

It quivers one more time and flits out of sight. I sit up and look at the shallow petri dish on the laboratory bench in front of me. I can just make out a tiny, whirling dot and suddenly feel like I’ve been Alice in Wonderland, peering through a tiny door into another world.

Earlier that morning, the sea butterfly had been swimming through clear, deep waters that surround the island of Gran Canaria. This parched volcanic outcrop lies 100 kilometres (60 miles) west of mainland Africa, at the same latitude as the desert border between Morocco and Western Sahara. I had come to meet Silke Lischka, a sea butterfly expert who had kindly agreed to help me find one of these beautiful, peculiar molluscs that could easily have sprung from the imagination of a storyteller. I desperately wanted to see one for myself, to check that they are real. And I wanted to see them now because their time might be running out. These fragile animals could one day soon begin to vanish from the seas, the early victims of climate change and a silent warning of troubles to come.

We had motored offshore on a black, inflatable research boat across the sea, flat like a swimming pool and only ruffled here and there by a gentle breeze. We found a good spot, stopped the engine, and Silke then lowered a plankton sampler into the blue water. Peeping over the side, I watched the rope paying out 15 metres (50 feet) or more, visible all the way as it dragged the white net down like a slender, upside-down parachute. On its return journey back to the surface the net sifted seawater, trapping anything bigger than a fine sand grain (70 microns, or 0.07 millimetres). Hauling the net back on board, Silke carefully unclipped the canister that had caught the siftings and tipped the contents, about half a litre of water, into a small screw-top barrel. I looked in and saw a blizzard of swirling particles, and immediately started imagining what we might have caught.

Six or seven times, Silke plunged the net down then dragged it back up, bringing in more minuscule treasures until she decided that we had enough to be getting on with. We kicked the engine into life and returned to land, passing flying fish that skittered through dry air on their improbable wings before plopping back down to where they usually belong.

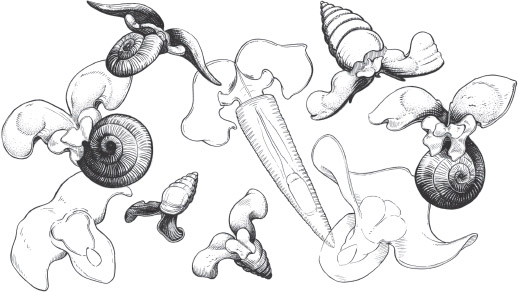

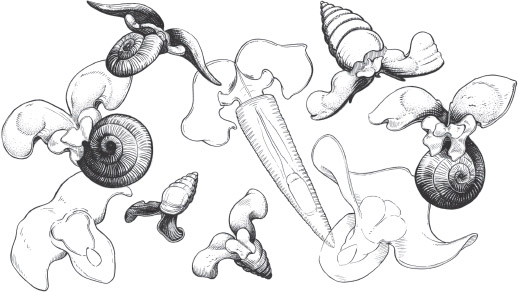

Back in the laboratory at PLOCAN, the Plataforma Oceánica de Canarias, we sat diligently working through the plankton samples, pouring out small pools of seawater and examining their contents through microscopes with up to 40 times magnification. We had captured a fidgeting, living galaxy. There were masses of minute crustaceans called copepods, with bodies shaped like tear drops and some with a single, red cyclopsian eye; they paddled through the water on pairs of long whiskery appendages and turned endless pirouettes, chasing their tails round and round. Fuzzy tufts of cyanobacteria, or blue-green algae, drifted past like tumbleweed. I spied some Noctiluca scintillans. Under the microscope these dinoflagellates (a type of green algae) look like transparent peaches. At night, in their millions, they transform the seas into a glittering light show of bioluminescence. There was a tunicate larva with a small head and wriggling tail; how strange to think that, in time, it would settle onto the seabed, absorb its brain and become a plant-like sea squirt. I saw radiolarians like exquisite, many-pointed stars, pulsing cuboid jellyfish larvae, and foraminifera with coiled, chambered bodies that could be mistaken for miniature ammonites. But most splendid of all, I was quite convinced, were the gastropods with tiny wings.

For a while we saw no sea butterflies and I began to worry that I’d missed my chance, that it was too late in the season and the Atlantic had already become too cold and empty of food for them to still be hanging around. But we carried on, in hushed concentration, working our way through the barrel of seawater, until eventually Silke let out a little giggle and told me to come and take a look. She had found a small specimen of Limacina inflata (sea butterflies tend not to go by common names, only their scientific labels). Her find seemed to break the spell of the hiding sea butterflies, and suddenly plenty more showed themselves. Silke spotted a different species, not with a spiralling shell but with a delicate, conical tube instead. I began to get my eye in and found a sea butterfly for myself and it felt all the more special. I was the first person ever to lay eyes on that particular tiny creature.

‘They look like little snitches,’ said Silke, chuckling. And they do. When J. K. Rowling created the game of quidditch, played on broomsticks by the pupils at Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry, and the small golden ball with wings (which Harry Potter caught many times and swallowed at least once), I’d like to think she was inspired by sea butterflies. I watched them, transfixed, as they spun around, busily inspecting their shrunken sea as if they had somewhere important to get to. Soon, I became convinced that I was a natural-born sea butterfly-spotter. I spied sea butterfly larvae, which are so much smaller than the adults. Side by side they were pea and grapefruit. The young ones haven’t yet grown wings but have two lobes that are covered in tiny wriggling hairs and whir in circles, like an industrial floor-polisher. The movements of these energetic adolescents made the water around them glimmer and dance in a certain way that I learned to recognise and zero in on. And I found another minute mollusc with a spiralling shell that looked similar to the rest but with one important difference. I showed it to Silke and she raised her eyebrows at me, smiling; I knew I had earned brownie points. It was a heteropod, a distant relative of sea butterflies from another deep division of the gastropods. Unlike the sinistral sea butterflies, this one had a shell that twirled to the right.

Sea butterflies are also known as pteropods, the ‘wing feet’ creatures (just as pterosaurs were ‘winged lizards’). These most unlikely gastropods have wings instead of feet, which they use to swim through open seas worldwide, occupying the biggest living space on the planet. They are perhaps the most abundant animals that almost nobody has heard of.

Other pteropods, known as sea angels, also fly about underwater, but these have lost their shells. Instead, to protect themselves, their bodies are loaded with noxious chemicals that attackers soon learn to avoid. Their chemical defence is so effective that small crustaceans called amphipods have learned to kidnap sea angels and carry them around, keeping them alive, like personal bodyguards. However, don’t be fooled by the angelic appearance of the sea butterflies’ shell-less relatives. Sea angels are compulsive predators that hunt exclusively for sea butterflies. They have keen eyesight to spot their prey, fast wings to pursue them, and suckered tentacles to grab them and wrench them out of their shells in a violent battle of angels and butterflies.

Sea butterflies themselves get their food in an altogether gentler fashion. They cast webs made of sticky mucus and – just like spiders – they trap their food. Among the things that often wind up in their nets are crustacean and gastropod larvae (including of their own kind), phytoplankton, and obscure, vase-shaped animals called tintinnids. When it’s ready, the sea butterfly hauls in the whole lot, eating its dinner, web and all.

Their gossamer webs are difficult to see but in the 1970s and '80s, two dedicated sea butterfly researchers found a way. Ronald Gilmer and Richard Harbison from Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Massachusetts spent a lot of time scuba-diving all over the world, tracking down these minute creatures and observing what they get up to in their natural habitat (many sea butterfly species grow large enough as adults to be seen with the naked eye). They would take a bottle of crimson dye with them and squirt drops into the water near sea butterflies to illuminate their webs. The animals would cast their nets and then hang motionless in the water – neither rising nor falling – giving Gilmer and Harbison the idea that sea butterflies might use their feeding apparatus to help them stay afloat, rather like the way that female argonauts use their shells.

Sneaking up and gently nudging them, the divers witnessed the sea butterflies’ escape response: they quickly jettison their web, then either flit angrily away or pull in their wings and drop into the depths. Sea butterflies are good swimmers but they use up a lot of energy in the process. Many are negatively buoyant, and have to keep swimming or they sink. There are clearly benefits to be had from floaty nets, like tiny parachutes, that give them a break from all the incessant flitting.

There’s a lot we still don’t know about how sea butterflies move around their open ocean world. Silke shows me a video she shot of an Arctic species drifting through a large glass jar. She gently stirs the water and the sea butterfly stops beating its wings, holds them stiffly above its head and seems to ride the currents like a hawk on a thermal.

Sea butterfly procreation is especially curious. In some species there are separate males and females that will pair up, grab hold of each other’s shells, and swim together in spirals through the water for a minute or two while the male transfers sperm to the female. She will then lay strings of fertilised eggs, which she may carry around with her, stuck to her shell, before the young hatch and swim off. Meanwhile, some species are sequential hermaphrodites; they all start life as males then later switch sexes, becoming females. Early in the spawning season, when there are only male sea butterflies, they will mate with each other. Males undertake a mutual sperm exchange, then hold on to their partner’s donation until they turn into females. Then, all the new female need do is to fertilise her eggs using the donated sperm she’s saved up from her earlier, male-only encounter. It might initially seem like an odd way of doing things, but it makes sense in the big, wide open ocean where finding a partner of the right species and the opposite sex can be difficult: by swapping genders and having sex in this unusual way, the sea butterflies increase their odds of finding a suitable mate.

Pteropods are not the only gastropods that have abandoned the sea floor. Janthina is a genus of snails with vivid purple, spiralling shells that float on the sea surface, buoyed up by a raft of frothy bubbles. Glaucus atlanticus, known as the sea swallow, is a shell-less gastropod that also occupies this two-dimensional world; it hangs upside down from the surface rather like a water boatman in a pond, with long fingerlike projections that store stinging cells scavenged from its favourite food, the Portuguese Man-of-war. Spanish Dancers, another no-shell gastropod, can usually be spotted crawling across coral reefs but occasionally they fling themselves into the water and swim along with flamboyant ripples of their mantle, like a flamenco dancer’s twirling skirts.

All of these gastropods are drifting and swimming through seas that are silently changing and many of them – especially the sea butterflies with their tiny, fragile shells – could soon find their world turning sour.

Silke Lischka had come to Gran Canaria not to show me sea butterflies but to take part in a major, two-month research expedition, designed to help us understand more about what the future holds for these delicate molluscs and other minute sea creatures. Despite the gruelling work schedule, Silke had devoted her well-earned day off to helping me in my search, but she had to get back to studying what happens to sea butterflies when their watery world is threatened.

The problem of pH

For a little over two centuries people have been digging out and pumping up ancient black stuff from deep underground and using it to produce heat and light and food and to propel themselves about the place at ever-faster speeds. Burning all this coal and oil sends carbon dioxide in colossal quantities into the air where, together with other pollutants, it insulates the planet like a blanket, trapping the sun’s radiation and leading to the various complex effects of anthropogenic climate change. But not all the so-called greenhouse gases released from burning fossil fuels stay in the atmosphere. Around a third of all the carbon dioxide ever made by human activities has been absorbed into the oceans.

If it wasn’t for the saltwater that covers seven-tenths of the planet, the problems caused by climate change would already be unspeakably worse than they are today. Every hour, the oceans absorb a million tonnes of carbon. In less than four hours they absorb the equivalent of the annual carbon emissions from a coal-burning power station. We all have a lot to thank the oceans for.

The problem is that carbon dioxide doesn’t just sit unnoticed in the oceans, but it has its own particular effect. When it reacts with seawater, carbon dioxide lowers the pH, making the oceans more acidic. Measurements show that since the dawn of the industrial revolution, ocean pH has fallen by 30 per cent. If we carry on with business as usual and do nothing to cut carbon emissions, experts confidently predict that by the end of the century ocean pH will have dropped by 150 per cent. There’s no question about it: this is purely a case of indisputable chemistry.

The term ‘ocean acidification’ first became popular in 2003, when Ken Caldeira and Michael Wickett published a paper in the journal Nature. They calculated that if we go ahead and burn all the remaining fossil fuels, the oceans will become more acidic than they’ve ever been in the past 300 million years. Whether things will ever get that bad we’ll see, but the point is that the chemistry of the seas is already changing.

Ocean acidification gets far less attention in the public eye compared to other threats linked to climate change. All we tend to hear about are rising temperatures and rising sea levels. Nevertheless, away from the media spotlight, researchers are beginning to untangle an important, difficult question: how will marine life react to acidifying oceans?

The fact is that the seas aren’t exactly transforming into a caustic acid bath that would strip your skin off when you jump in. Surface waters of the ocean are still mildly alkaline, with an average pH of 8.1, compared to pH 8.2 200 years ago (the pH scale is logarithmic, which is why a drop from pH 8.2 to 8.1 equates to a 30 per cent change). Pure water has a pH of around 7; acids are below that, with milk at pH 6.5, lemon juice at pH 2 and stomach acid at pH 1. At the other end of the scale are strong alkalis, like household bleach with a pH over 12.

By 2100, average ocean pH could be down to 7.8, which is not exactly stomach acid, but in fact around the same pH as human blood. However, many marine organisms are adapted to living in water that has a fairly constant pH. Even a minor tweak to seawater pH could be enough to throw all sorts of things out of whack.

Laboratory studies on the effects of falling pH on marine life are producing plenty of findings, some of them rather unexpected. In water with carbon dioxide bubbled through it, young clown fish lose their sense of smell and become deaf, making it more likely that in the real world they would blunder into a predator or have trouble sniffing and hearing their way home to a coral reef. If the movie Finding Nemo had been set in the future, the little clown fish would probably have stayed permanently lost (or been eaten). Other fish species could become more anxious as the seas’ pH drops. Californian rockfish kept in tanks of more acidic water became uncharacteristically shy, spending much of their time lurking in darkened areas and staying away from the light.

Ocean acidification could also make the seas more toxic in other ways. Lugworms live burrowed into sandy and muddy shores across northern Europe, where they are important food for wading birds and fish. You won’t often see them, but they leave distinctive worm casts across beaches at low tide, like squeezes of sandy toothpaste. Recent studies show that copper, a common contaminant of coastal waters, is much more toxic to lugworms in acidified seawater. When pH drops, copper kills lugworm larvae and damages the DNA in lugworm sperm, making them swim more slowly and reducing their chances of reaching a fertile egg and forming an embryo.

These various subtle effects on behaviour and toxicity are difficult to predict, and researchers have to work backwards, unpicking the story and figuring out why these changes take place. However, for one particular group of marine species the effects of ocean acidification are much more foreseeable.

Calcifiers are a mixed gathering of marine organisms that all produce calcium carbonate in some form, as exoskeletons or shells. There are calcifiers stationed all the way through marine food webs, from microscopic, sun-fixing plankton, to sea urchins, starfish and corals, crustaceans and worms, and of course all those molluscs with shells. And these carbonate-makers are all in the firing line of ocean acidification.

The calcifiers’ problems begin with the fact that calcium carbonate dissolves in acid. If you place a chicken’s egg (also made of calcium carbonate) in a glass of vinegar you’ll see this happening for yourself, albeit to an extreme degree: the shell dissolves leaving a naked egg, held together by a thin membrane. This sort of approach is the only way, so far, that anyone has investigated how acidifying oceans might affect argonauts. When Jeanne Power studied argonauts in Sicily in the early years of the industrial revolution, she had no reason to think of testing the effect of pH on pieces of their shells. When Kennedy Wolfe at the University of Sydney, Australia tried it in 2013, he found that at pH 7.8, argonaut shell begins to dissolve. This arises from the fact that female argonauts make their shells from an especially fragile form of carbonate, called high-magnesium calcite, which readily dissolves at lower pH. Argonaut shells also lack an outer, organic layer that could help protect other molluscs from acid attack (a spongy, thick protein layer is one reason molluscs can survive the corrosive conditions at hydrothermal vents).

What we don’t know is how argonauts might react to falling pH while they are still alive (the animals are too rare and difficult to keep in captivity, so no one has tried this). Jeanne watched her animals use web-like membranes to fix damaged shells. Would argonauts do the same thing if their shells began thinning and dissolving in acidifying waters? Perhaps, but there is an added problem. As well as making their shells more likely to dissolve, ocean acidification also makes it harder for molluscs to make and mend their shells.

When carbon dioxide reacts with water it not only releases hydrogen ions, causing a drop in pH, but also reduces the concentration of carbonate ions (this happens because they react with hydrogen ions, forming bicarbonate). The problem for calcifiers is that carbonate ions are the basic building blocks they use to produce their shells. Many species need seawater to be supersaturated with carbonate ions to be able to form enough calcium carbonate for their skeletons and shells. As the concentration of carbonate ions drops, and seawater becomes undersaturated, calcifiers must devote more energy to pumping ions around their bodies and maintaining the process of shell-making. Molluscs have to concentrate carbonate ions in the gap between their mantles and their shells where new shell material is made. This can drain energy away from other vital functions, like reproduction and growth.

To make matters worse for shell-making molluscs, carbon dioxide also diffuses from water directly into their bodies, mostly through their gills. Left unchecked, a drop in the pH of body fluids can impact all sorts of important processes, in particular the functioning of enzymes. These proteins govern reactions around the body and they work best within a narrow pH range and will slow down or even stop if their surroundings become too acidic or too alkaline. As a consequence, organisms have evolved complex balancing mechanisms to maintain the right pH. Imagine a living body is a room, and acid-causing hydrogen ions are tennis balls that pour in through an open window; to prevent the tennis balls filling the room, and lowering the pH, you have to push them back out through the letterbox. Living bodies have various ways of keeping pH in balance, but they require yet more energy.

Lots of studies have tested how all sorts of calcifiers respond to falling pH and falling carbonate ion concentration. Coral reefs are a major focus for these studies because various components of these important tropical ecosystems form carbonate skeletons. This includes hard corals, the ‘bricks’ that form a reef’s foundations, together with encrusting coralline algae that cement the reef together. It’s possible that corals may adapt to gradual acidification and survive, but it’s easy to be pessimistic about the future of reefs. The combined impacts of overfishing, coastal pollution, acidification and warming seas (which cause corals to lose the colourful, microscopic algae in their tissues, bleaching them white and in many cases killing them) lead many experts to think that coral reefs as we know them could be extinct by the end of the century.

Molluscs have also been the subject of extensive acidification research, in part because the valuable seafood industry could be left in ruins if edible species start disappearing. Clams, mussels, conchs, scallops, oysters and many more have all been plucked from their salty homes, moved into laboratory aquariums and exposed to seawater at various pH and carbon dioxide levels while scientists watch to see what happens. Initially, researchers mostly used mineral acids to simulate ocean acidification. They now tend to bubble carbon dioxide through water to more accurately mimic the real world. In most studies, as pH drops, the molluscs get in all kinds of trouble.

Flimsy and misshapen shells and lower calcification rates (the laying down of new shell material) are commonly seen in molluscs kept in seawater of lower pH and higher carbon dioxide than they’re used to. Mussel byssus threads lose their stickiness, and many molluscs suffer from a suppressed immune system. Some researchers have observed molluscs swimming and crawling more slowly in acidified waters. Embryos and juveniles seem to be especially vulnerable. They take longer to mature and many don’t survive.

It follows that with all the demands on their energy supplies, molluscs commonly respond to acidifying waters by boosting energy production or metabolic rate. They need energy to grow, to patch up shell damage, to try desperately to maintain their pH balance and ultimately to stay alive. For many species, all of these demands can become too taxing and they suffer, but this isn’t always the case. Lab studies of ocean acidification regularly throw up unexpected and contradictory results.

Some molluscs seem quite unfazed by lowering pH and rising carbon dioxide, and some positively thrive. It seems to depend partly on where in the world the molluscs come from. The Blue Mussel is one species that confounds scientists by behaving differently in acidification studies around the world; in some places they are robust, elsewhere they do badly. It suggests that there is some degree of local adaptation to varying baseline conditions – pH is not the same everywhere in the oceans – and that some populations could be more likely to survive than others.

Slipper Limpets are another odd species. They have continued to grow happily when carbon dioxide levels around them were ramped up to 900 parts per million (or ppm; currently, the atmosphere is around 400ppm). When Common Cuttlefish are exposed to carbon dioxide at a massive 6,000ppm, some individuals remain unaffected and some actually do better than others kept in normal, mild conditions. After six weeks at extreme carbon dioxide levels, their internal cuttlebones, made of calcium carbonate, are bigger and heavier. Cephalopods, including these cuttlefish, are generally thought to have more sophisticated internal balancing mechanisms than other molluscs. They are also good at boosting their metabolism when they need to, which goes some way to explaining why cuttlefish get on so well in such extreme conditions. But plenty of puzzles still remain.

As it stands, the prognosis for shelled molluscs in acidifying oceans is mixed. Some species may be able to tough it out, while others will come to grief. But for sea butterflies in particular the prospects aren’t looking too good.

Sea butterflies have been labelled the ‘canaries in the coal mine’ of acidifying oceans. These sensitive creatures could be the sentinels, warning of dangers ahead. In the first half of the twentieth century, miners would take down caged birds with them to detect toxic gases, mainly carbon monoxide; when the birds passed out and died, the miners knew it was time to put on breathing apparatus and make a quick escape. For sea butterflies in acidifying seas, the coal-mine analogy is rather ironic – or perhaps poetically dismal – seeing as it was coal that kick-started the problem of ocean acidification in the first place.

With their dainty, thin shells it comes as no great surprise that sea butterflies are among the more sensitive molluscs; they don’t have much to lose shell-wise in the first place, so when exposed to acidifying waters they are especially vulnerable. Dire predictions suggest that swathes of the ocean could be out of bounds for sea butterflies in the years ahead.

Problems are likely to be most severe in polar seas, where acidification is expected to hit soonest and hardest, because cold water naturally holds more carbon dioxide. In parts of the Arctic and Antarctic, it’s predicted surface seawater could become undersaturated with carbonate ions – and corrosive to unprotected shells and skeletons – within the next few decades. These frigid seas are also important parts of the sea butterflies’ domain.

It’s not easy to gauge how sensitive sea butterflies are to falling pH and rising carbon dioxide because they’re flighty in more ways than one: they’re especially tricky to keep alive in captivity. No one has yet worked out how to breed them, and they can’t be shipped between labs around the world, so the only way to study them is to go to where they are in the wild.

The search for sea butterflies lured Silke Lischka deep inside the Arctic Circle. Among various research trips, she spent a winter in almost perpetual darkness illuminated from time to time by the Northern Lights. She was in Kongsfjord in the Svalbard archipelago, halfway between Norway and the North Pole, where a purpose-built research station makes it possible for scientists to live and work quite comfortably in this remote outpost. While she was there, sea butterflies were not difficult to find. Swarms of them would drift into the fjord and hover in the water right in front of the research station, and some days she could have sat on the dock and scooped them up in a bucket, but usually she puttered out in a boat and gathered her samples from deep fjord waters.

These were Limacina helicina, a close relative of the spiralling sea butterflies we found in Gran Canaria, and one of only a handful of sea butterfly species that live in the Arctic. After hatching over the summer, the juveniles have to survive a long, dark, hungry winter, hanging on until the sun returns in the spring, when they mature into adults, mate and produce the next generation.

With extreme care, Silke carried the young sea butterflies back to her laboratory on the shores of the fjord and kept them in a range of temperatures and carbon dioxide levels, including those levels expected by century’s end. Then she measured their shells and examined them through a microscope for signs of damage.

At higher carbon dioxide levels, the transparent shells became more scuffed, perforated and scarred compared to those kept in more normal conditions; the high carbon dioxide sea butterflies were also slightly smaller, suggesting they weren’t growing so well. The sea butterflies she hit with the combination of higher carbon dioxide levels and higher temperatures often didn’t survive.

Repeating her experiments with empty shells, Silke showed that living sea butterflies can resist acidification to some extent; they don’t get as badly damaged as empty, dead shells. But there’s no doubt that having to reinforce their dissolving homes, laying down more carbonate on the inside, puts a strain on the juveniles’ limited energy reserves. If this happened in the wild, the little sea butterflies would probably find it much harder to survive the winter.

Several other researchers have studied sea butterflies and uncovered similar gloomy forecasts of their demise. Clara Manno investigated sea butterflies in the far northern reaches of Norway. Her experiments showed not only that lower pH and higher carbon dioxide causes sea butterfly shells to lose weight, but she also revealed the confounding effect of freshwater. As sea ice and glaciers melt in a warmer world it’s expected that the salinity of surface seawaters will drop. When both pH and salinity were reduced, sea butterflies flicked their wings more slowly as they swam around Clara’s laboratory tanks, showing her that something was not right.

Like Silke, Steeve Comeau studied Limacina helicina in Svalbard, and found similar results, but he also ventured west to the Canadian Arctic, where he lived in a temporary research base perched out on the sea ice. Steeve collected his samples by lowering plankton nets through a hole in the ice. Back in the lab he found that the rate of calcification dropped by around 30 per cent in sea butterflies exposed to the carbon dioxide levels predicted by 2100.

In distinctly warmer waters, Steeve worked with larvae of a Mediterranean sea butterfly species. As he reduced pH, the larvae grew smaller, malformed shells. And he found that below pH 7.5, they didn’t grow shells at all – but they didn’t die. In the confines of the laboratory the naked sea butterflies seemed to get along just fine but there’s no knowing if they would survive in the wild. Nobody has yet found any naked sea butterflies in the oceans, but one research team has uncovered the next worrying part of the story: wild sea butterflies whose shells already seem to be dissolving.

In parts of the oceans, winds blowing across the sea surface cause deep, cold waters to upwell into the shallows. These deeper waters are naturally rich in carbon dioxide and undersaturated with carbonate ions. Nina Bednaršek has led studies of sea butterflies in two upwelling regions. The first, in 2008, was in the Scotia Sea that stretches between Tierra del Fuego, at the tip of South America, and the island of South Georgia in the Subantarctic. The second, in 2011, was along the western seaboard of North America, between Seattle and San Diego. At both sites, Nina found sea butterflies with signs of damage and shell decay similar to those seen in animals that have been through acidification experiments in labs. Her findings have been interpreted as a worrying sign of things to come.

Will it matter if sea butterflies start to disappear from the oceans? Will declines or shifts in their range send ripples of change through the rest of the open ocean ecosystems?

One way that a loss of sea butterflies would potentially matter is because they play a part in drawing carbon away from surface seas down into the deep and away from the atmosphere. They do this via carbon locked up in organic matter, mostly their faeces.

Clara Manno was the first to identify sea butterfly droppings. They are compact pellets, oval in shape, greenish brown and quite easy to spot once you know how. She calculated that a single sea butterfly produces around 19 droppings per day, and they sink rapidly through the water column. Sifting through sediment samples gathered from the Ross Sea off Antarctica, she calculated that almost a fifth of all the organic carbon sinking into the depths – the so-called organic carbon pump – consisted of pteropod poo. Add their abandoned mucous webs, plus their dead bodies that get dragged down by their shells, and it means sea butterflies could drive half of the organic carbon pump in some polar waters. It’s very difficult to predict exactly how things would change if sea butterflies were to begin abandoning acidifying waters in the Arctic and Antarctic. Other planktonic species could conceivably move in and take their place in the ecosystem, but there is always the chance that they would be less effective at removing carbon from the atmosphere and pulling it into the deep sea. If the organic carbon pump were to weaken, it would add yet another twist to the tangle of problems caused by climate change.

Without sea butterflies, there would also be a lot of hungry sea angels out there, as they eat little besides sea butterflies. Seabirds and fish also eat sea butterflies (although not exclusively); they in turn are eaten by bigger fish, as well as whales and seals, making sea butterflies a potentially crucial link in ocean food webs, including ones in which people are involved; there’s a series of short hops from plankton to sea butterfly to salmon to dinner plate. If sea butterflies vanish or shift their ranges, it’s possible the animals that eat them will also have to move, or find something else to eat, or go hungry. Exactly how important sea butterflies are as food for other animals, and whether ecosystems would be disrupted without them, is not clear. Much more research is needed.

It’s true that sea butterflies can be extremely abundant and, when they are, other animals will often zero in and stuff themselves. Silke described to me a day during her time in Svalbard when a huge flock of sea butterflies drifted into the fjord; hundreds of kittiwakes and fulmars sat on the sea, merrily picking at the submerged feast. Other researchers have counted 10,000 sea butterflies in a single cubic metre of water, but such high densities only occur in patches that come and go.

A major challenge that lies ahead for ocean acidification research will be to move on from single-species studies. It’s all very well knowing how individual animals react when exposed to acidifying seawater, but what happens when hundreds and thousands of organisms are all interacting, eating each other and competing for space and food? There’s one thing everyone agrees on when it comes to understanding the impacts of ocean acidification: it’s complicated. And most complicated of all will be predicting how entire ecosystems are going to respond. But researchers are finding ways.

How to probe an ecosystem

The departure lounge at Gran Canaria’s Las Palmas airport overlooks the runway, and beyond it the Atlantic stretches out to the horizon. For two months in the late summer of 2014, if passengers glanced up from their Starbucks coffee and gazed through the huge glass walls, they might have caught a glimpse of science in progress.

Nine orange structures nod gently in the sea. Each is a ring of floating pipes sticking up into the air and supporting the top end of a giant, tubular plastic bag; two metres (six feet) wide and 15 metres (50 feet) long, it hangs down into the water. Umbrellas keep the rain off, and rows of spikes stop birds from landing and pooping on them. Down on the seabed, piles of iron railway wheels are used as anchors to hold the equipment in place. These structures act as giant test tubes, designed to test the effects of ocean acidification, not just on single species but on the profusion of life that makes up an open ocean ecosystem.

There’s a bunch of clever things about these test tubes, which go by the name of KOSMOS, or the Kiel Off-Shore Mesocosms for future Ocean Simulation (mesocosm simply being a larger version of a microcosm, an encapsulated miniature world). For starters they are portable; they can be taken apart and shipped around the world, to repeat experiments in different sites, although this doesn’t come without its challenges. In Sweden, the KOSMOS tubes were frozen in by sea ice and the previous spring, in Gran Canaria, some were torn to shreds by huge waves whipped up in a storm.

The KOSMOS tubes also benefit from being very big. To do something like this on land would be laborious and far more expensive; it would involve building huge tanks and pumping in seawater, causing who knows what confusion and damage to minute sea life in the process. Much better to take the test tubes to the ecosystem, rather than the other way round. The sides of the giant plastic bag are carefully lowered to enclose 55,000 litres of seawater and everything in it. Then the stage is set to manipulate conditions inside the tubes, in this case to pump in carbon dioxide at varying concentrations, to mimic the effects of ocean acidification.

Once that’s done, the contents of the tubes are sampled every day or two. Water samples are extracted from the water column in each tube, traps at the bottom catch sinking particles and plankton nets are dragged through. Sampling all nine tubes can take hours, out in the dazzling, subtropical sunshine, but the really hard work has still to begin.

Back in the PLOCAN labs, the samples are divided up between researchers who eagerly whisk them off and plug them into an array of complex analytical devices, incubators and microscopes. By the time I pay them a visit, the 40-strong KOSMOS team has already had a few weeks to smooth out the kinks in their protocols but, even so, I’m amazed at how seamlessly the whole project is running.

Everyone knows what they’re doing and the order in which things need to happen, as if they are part of their own well-functioning ecosystem. And what’s more, they are all still smiling despite the long hours, roasting air temperatures, questionable coffee dispensed by the machine in the corridor and, for many of them, the repetitive, mind-numbing tasks – like counting sea butterflies.

Silke Lischka’s job, along with her assistant Isabel, is to sort through all the debris caught in the sediment traps at the bottom of the mesocosm tubes and, as she and I had done, scour the plankton net samples. They do things a little more systematically, though; each of them has a counting chamber made from clear resin block with a long, narrow groove in it, the same width as the microscope’s field of view, into which they pour the samples. They work their way along this elongated drop of water, counting sea butterflies as they go. Imagine an underground train driving slowly past while you stand on the platform counting all the people inside; you’re much less likely to miss anyone, or count twice, compared to standing by a crowded swimming pool and doing a head count. A tally of sea butterflies is kept using an old-fashioned, mechanical counter with typewriter keys that clack when they’re pressed and give a satisfying ding when they reach 100.

To get through all the samples takes hours, glued to a microscope, sometimes through long, sleepless nights. But I get a strong sense that everyone involved, especially Silke, knows why this is all worthwhile. They are contributing their part to a big, complex picture, probing the ecosystem from top to bottom, from the uptake and use of nutrients and the release of gases into the air, to viruses, phytoplankton and zooplankton. It’s too early to say how the experiment is going, how the sea butterflies and all the other parts of the ecosystem are responding to different carbon dioxide levels, but by the end of the project, and following a great deal of data-crunching, the team will take a step back and trace a labyrinth of invisible connections.

Similar studies have been carried out already in Arctic waters and off the coast of Scandinavia, but this is the first time the KOSMOS mesocosms have been deployed in open seas. Beyond the edge of continental shelves, these clear, blue, nutrient-poor waters are representative of what two-thirds of the oceans look like. Understanding what happens here is a major part of predicting how life across the planet will respond to ocean acidification.

Head of the KOSMOS project is Ulf Riebesell from GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel in Germany. I catch up with him after he has stayed up all night working on the latest stage of the experiment. The idea is to simulate the upwelling events that regularly take place when a steady current sweeping in from the north stirs up eddies in the island’s wake, drawing deep water to the surface. The team used an enormous plastic bag to collect 80,000 litres of seawater, weighing 80 tonnes, from seven miles offshore and 650 metres down; the collecting bag took three hours to reach the surface, where it bobbed like a bloated whale. After they were set back a day by a broken water pump, the deep water was injected into the mesocosm tubes and all finally went according to plan. Now the team are on standby, waiting to see what effects unfold. They expect the nutrient-rich deep water will kick-start a phytoplankton bloom, and with it a feeding frenzy that will sweep through the rest of the ecosystem.

‘It’s like a big rain shower over a desert,’ is the way Ulf describes the upwelling event to me. He is still wide awake and brimming with enthusiasm when we sit down to chat about the project. There is one thing in particular I want to ask him about, something that has been bothering me for a while: the passing of time.

Why time matters

Most ocean acidification studies take place over the course of hours and days and a few, like KOSMOS, keep going for months. But out in the real world, there is a hundred years to go before ocean pH is expected to reach extremely low levels. In that time, will marine life be able to adapt to the creeping changes in the world around it?

This is a major limitation of most ocean acidification studies; critics point out that they take place too fast, and don’t continue for long enough, to truly mimic acidification in the oceans. A few longer-term studies hint that there is scope for adaptation, but perhaps only up to a point. Ulf’s research group has bred phytoplankton called coccolithophores for 1,800 generations in high carbon dioxide conditions. These microscopic algae live inside clusters of calcium carbonate discs – collectively called the coccosphere – making them likely victims of acidification. However, over time, the laboratory population became more robust to falling carbonate saturation and lower pH.

The experiment acted as a form of artificial selection. The high carbon dioxide treatment slowed the growth rate of some coccolithophores, probably because they needed more energy to keep building their carbonate skeletons. Meanwhile some of them were more robust and were able to maintain their growth rates, perhaps even growing faster. These individuals were the ones that reproduced more rapidly, passing on more of their genes to the next generation. Slowly, in laboratory conditions, the acidified coccolithophores became adapted to their shifting water chemistry.

It remains unknown exactly how the coccolithophores’ physiology changed; it’s possible that as generations went by, they became more adept at ramping up metabolic rates and pumping ions around to maintain pH balance. Or, there may be some other as-yet unidentified mechanism that allows them to survive.

Could other calcifiers adapt to acidifying waters like coccolithophores? To repeat the experiments on anything that lives longer than these microbes would take an insanely long time. Coccolithophores have a generation time of a single day. It took five years to study them for 1,800 generations. For organisms like sea butterflies that have generations lasting a year, these experiments become quite unthinkable. Plus, it’s well known that organisms with short generation times evolve quickly, compared to species that take longer to mature and reproduce (this is because the genomes of short-lived species are copied more frequently and errors quickly build up in their DNA, leading to more genetic variation that natural selection will act on). Coccolithophores are also highly abundant, with up to 10 million of them in a litre of seawater. It means that coccolithophores are inherently more adaptable to environmental changes than larger, rarer species like sea butterflies. And like Steeve Comeau’s naked sea butterflies, the big unknown is whether carbon-resistant coccolithophores would survive out in the oceans, where there are masses of other species all competing for resources and space.

Even those organisms that can change their ways and adapt to a high carbon dioxide world may eventually still lose out. As the oceans continue to acidify, the cost of concentrating carbonate ions and building skeletons and shells will keep on steadily rising until calcifiers can simply no longer afford to make their homes.

‘There are certain limits you can’t pass,’ Ulf tells me.

The century of acidifying seas that lies ahead will be unavoidably long and slow compared to the short-term studies aiming to forecast the future (after all, the only way to really know how the oceans are going to respond is to sit back and watch what happens in real time, but that’s hardly the point of studies like this). However, the rate at which ocean acidification is now taking place is a mere beat of a sea butterfly’s wings compared to the millennia that rolled by in previous climate change events, the ones that came and went before modern humans showed up. Sceptics point to these past events, to times when carbon dioxide levels were naturally high without humanity’s input. And look – look at all those things that were alive back then and are still here now. There are still corals and plankton and all those molluscs with shells. They didn’t melt away before, so why should we believe that will happen this time?

Things are different now. Given enough time, and a slow enough pace of carbon enrichment, the oceans themselves respond to ocean acidification and lessen its effects. Deep down on the sea floor there are vast deposits of calcium carbonate sediments, made from the fossilised remains of calcifying creatures – mostly coccolithophores and foraminifera – that lived and died over millions of years. In the past, carbon dioxide levels have risen in the atmosphere as is happening now, but from other sources besides human activities. The pH of shallow seas fell and, over the course of many centuries, those surface waters sank down, until they reached the deep carbonate sediments, causing them to dissolve and release carbonate ions. It meant that levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere were decoupled from the saturation of carbonate ions in the seas; while atmospheric carbon dioxide increased, it didn’t drag down carbonate saturation with it. In essence, the oceans had their own colossal mechanism that buffered against acidification, which explains why many creatures with chalky skeletons were able to survive previous climate change events. In the past, calcifiers were protected from acidification by their ancestors – calcifiers of earlier eons – whose remains accumulated on the seabed. But now that link has been broken. The problem is, the oceans’ inbuilt balancing mechanism takes 1,000 years or more to work, because that’s how long it takes shallow waters to spread through the deep ocean. This time around, we don’t have 1,000 years to wait.

Anthropogenic climate change is taking place much faster than anything the planet has experienced before, and the oceans can no longer keep pace with carbon emissions. The rate of uptake of carbon dioxide into the oceans far outstrips their ability to buffer against falling pH. Now, carbon dioxide levels and carbonate saturation are locked in relentless decline; side by side they drop together. The oceans today are slaves to the atmosphere.

A major talking point for climate change – and a target for sceptics – is the issue of how much experts agree on the facts. Increasingly, scientists worldwide are standing up and making it abundantly clear that they do agree, by and large, on the causes of climate change and the global troubles that could lie ahead. On a similar note, do experts agree that ocean acidification is happening, and that it’s a problem for the seas? A 2012 survey of experts suggests that consensus is strong, at least when it comes to the bigger issues.

Jean-Pierre Gattuso from the Laboratoire d’Océanographie in Villefranche, France, led a survey asking 53 ocean acidification experts how much they agreed, or disagreed, with a list of statements. Almost all the experts agreed – without question – that ocean acidification is currently in progress, that it’s measurable, and that it is mainly caused by anthropogenic carbon dioxide emissions ending up in the oceans (many pointed out that in coastal waters other pollutants, such as excess nutrients, can also affect pH).

As is the scientist’s prerogative, many respondents picked apart the questions being asked, pointing out problems with the wording: ‘What do you mean by “most”?’, ‘What does “adversely affect calcification” mean?’

In many cases, they emphasised the lack of certainty, the lack of long-term studies and the variable responses of different organisms. Without more data, it’s difficult to be sure how food webs and fisheries will fare in a more acidic world. However, experts did agree that calcifiers, with their chalky skeletons and shells, are the marine species most likely to lose out.

Experts are also largely agreed that the ocean-atmosphere system has momentum. Even if carbon emissions were eradicated tomorrow, the oceans would continue to acidify for centuries to come. As one scientist put it, ‘This is physical chemistry … I don’t think there is any other possibility.’ Does this mean that ocean acidification studies, like the KOSMOS mesocosms, are simply casting predictions about a global experiment that will run on regardless of their findings, and regardless of how humans behave in the next few decades? If ocean acidification really is inevitable and unstoppable, maybe it doesn’t help to wrap our minds around the reality of how bad it will get. Perhaps we are better off not knowing.

I don’t think so. There’s no avoiding the uncomfortable truth that the only way to limit ocean acidification and the other problems of climate change – to stop the situation from becoming utterly disastrous – is to make drastic cuts to escalating carbon emissions, and to do it now. Decision-makers need to see these predictions, based on the best available science, of what a future world will look like so they can understand what it is that we’re losing, and why action must be taken. The same goes for the rest of us. For most people, most of the time, ocean life is out of sight and out of mind, but there are plenty of good reasons why we should all sit up and take notice, and start caring about these vital, hidden worlds.

I felt a sense of great privilege peering at those sea butterflies and the other planktonic creatures as they whizzed around their glass-walled world, oblivious of me watching them. It was as if I had been let in on some of the oceans’ greatest secrets, but who knows how much longer they will all be there? Of those spinning specks of life, some will be winners and others losers in the lottery of warmer, stormier and corrosive seas. And the really frightening thing is that the problems of the oceans don’t stop at carbon. We are fishing deeper and further from shore than ever before, plundering wild species and treading paths of destruction through fragile ocean habitats. Dead zones are proliferating; garbage is piling up, transforming the open seas into toxic, plastic-flecked soup. All these troubles and many more combine, acting in concert to worsen each other. It’s easy to feel overwhelmed, and utterly helpless in the face of relentless bad news.

But the problems are not all far away, nor are they out of our hands. It matters what each one of us decides to do, what we choose to eat, what we buy and what we throw away. We have the power to lighten our impact on the blue parts of our planet. Curbing as many individual problems as possible will give the oceans a chance to rest, to recover and restore themselves, and resist the impacts of climate change. If we act now, there’s hope that in the years ahead there will still be a wealth of wonders in the oceans; there will be food for millions of people, from nutritious bowls of clams to the indulgent treat of flinty, raw oysters; sea snails will sneak up on sleeping fish and scientists will probe their spit for new inspirations; each night, nautiluses will rise from the inky depths, as they have done for hundreds of millions of years; tiny snails will fly around the open sea, spin webs to catch their food and be chased by other flying snails that don’t have shells, and octopuses that do. And there will still be beautiful shells washing up on beaches, where people will find them and wonder where they came from, and how they were made.