Tne Medical Profession

The winter months brought winds from the desert that were cold and dry. In March and April, the south wind, known in modern times as the Khamsin, blew in from the surrounding deserts. This wind continued for a couple of days at a time, carrying with it sand and dust which sometimes caused a thick yellow fog that covered the sun. Climatic conditions at this time of year exacerbated breathlessness and coughing fits, from which many elderly people suffered. In our imaginary family, Perenbast’s mother, Nefert, often became ill during these months and had to consult a doctor. Her granddaughter, Meryamun, was married to a renowned physician, Amenmose, and he offered advice and suggested treatments to alleviate Nefert’s symptoms.

The Doctors

Amenmose was a priest-doctor, a medical practitioner of the highest status; he undertook duties in the temple on a part-time basis, and followed his medical profession in Thebes for the remainder of the year. Doctors of his rank were known as wabau, a title which indicated that they regularly underwent ritual purification to allow them to enter the presence of the god’s statue. These doctors often specialized in particular areas of medicine, and were known as priests of the lioness deity Sekhmet.1

In predynastic times, tribal and village chieftains performed magical acts and rituals to heal members of their communities. Eventually, the most powerful chieftain became king; he was believed to possess special healing powers which, in turn, he delegated to special categories of priests. Originally, these men probably acted as religious functionaries; they mediated between the goddess Sekhmet and their patients and tried to persuade the deity to remove all illnesses and afflictions. However, over the generations, through a process of trial and error, the priests gradually acquired practical skills and medical knowledge: they observed their patients, learnt to diagnose their symptoms, and were able to offer help and prescribe treatments.

Sacred Lake, Temple of Hathor, Denderah. Each temple had a lake where priests washed and purified themselves before entering the temple. This lake, now dry, was once fed by an underground source which still provides sufficient water to support a group of palm trees. Graeco-Roman Period.

The medical profession was evidently well organized even in the Old Kingdom; however, the first king of Egypt (who ruled long before that date) was credited as the author of a treatise on anatomy and dissection. At the start of the Old Kingdom, Imhotep (First Minister of King Djoser and architect of the Step Pyramid at Saqqara) was renowned as a great healer; later, the Egyptians worshipped Imhotep as the founder of medical science, and eventually the Greeks identified him with their own god of medicine, Asklepios.

No records survive to provide information about medical training. Some temples acquired special reputations for healing, and patients were taken there to undergo particular forms of treatment. Amenmose and his colleagues may have studied in the ‘House of Life’ associated with these temples, where the wabau perhaps spent some periods of their temple duty in teaching students and attending to patients. It remains unclear how medical training was organized; for example, we do not know if it involved formal examinations as well as practical instruction.

The wabau headed the medical hierarchy; doctors in a lower grade, known as swnw, were State employees who treated patients suffering from a wide variety of illnesses; they worked especially at building sites, burial grounds, the Royal Court, and with the army. Other health care workers included magicians (sau) who played an important role in towns and villages; specialist midwives responsible for delivering babies; and nurses, masseurs and bandagers who assisted the doctors.

The practice of mummification familiarized the Egyptians with the idea of autopsying a corpse and ensured that there was no taboo on human dissection. In later times, many Greeks chose to undergo their medical training in Alexandria in Egypt, where they could perform autopsies prohibited in their own country. Mummification and bandaging the body also gave the Egyptians a detailed knowledge of human anatomy and the techniques required to bind dislocated and broken limbs.

Medical Concepts

Nefert’s medical practitioner visited her at home, and prescribed several treatments for her various ailments. Both irrational (magical) and rational methods were employed to heal the sick, and they were considered to be equally valid and efficacious. If the cause of the problem was outward and visible (for example, an accident), then the practitioner usually recommended objective and scientific measures, based on his observation of the patient, knowledge of anatomy, and general experience of disease and illness. However, sometimes the cause was inward and hidden (for example, a virus or bacterium which resulted in an infectious disease), and then the healer might use magic. The Egyptians were not aware of the true nature of such diseases, and often attributed them to a ‘devil’ caused by the ill wishes of the dead or an enemy, or the punishment of the gods. In these cases, the doctor employed incantations to drive the ‘devil’ out of the patient, sometimes accompanying these spells with ritual acts and gestures enacted on the patient or, if absent, on a substitute figurine. Rational and magical methods both had a role to play in healing the sick, but the choice of treatment depended on a patient’s particular wishes and circumstances.

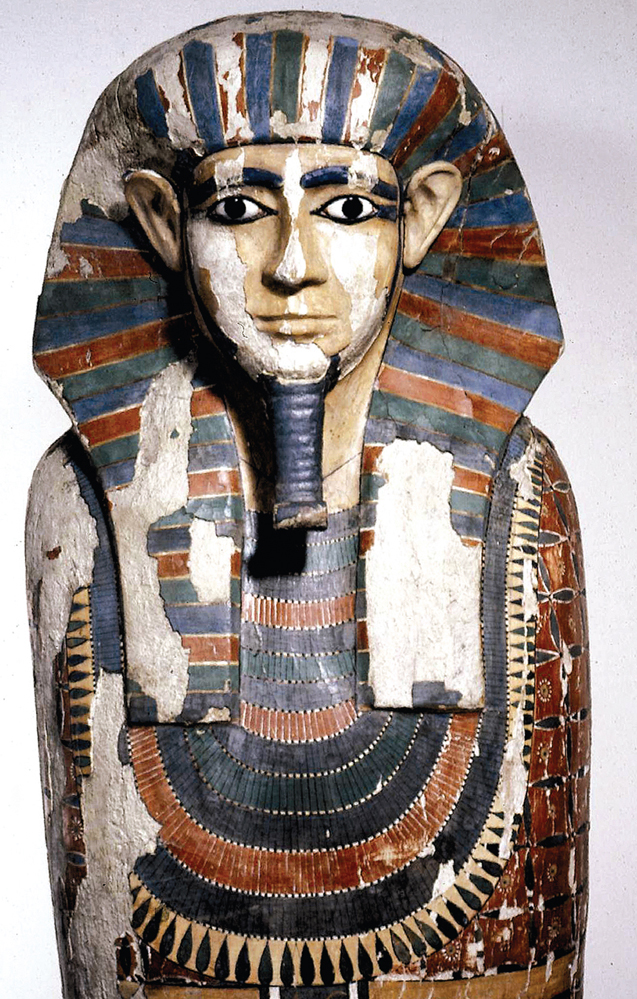

Gilded stucco head-piece from a mummy. When immigrants from other parts of the Hellenistic world and Roman Empire settled in Egypt, many adopted Egyptian funerary customs, particularly mummification. This example shows some of the developments in style and decoration that were introducedfor these new, wealthy clients. From Hawara. Graeco-Roman Period. Manchester Museum.

Some rational treatments were therapeutically viable, but others would have had little impact on the patient’s condition. One serious limitation of the medical system was the Egyptians’ erroneous view of the basic functions of the body. It is easy to see how they may have developed these inaccurate ideas: although the practice of mummification had familiarized them with human anatomy and the general disposition of the internal organs, they may never have had an opportunity to examine the internal system while the patient was alive and the organs were still functioning.

Egyptian medicine was dominated by the idea that the main focus of human physiology was the metw; these were envisaged as a network of ‘canals’ – vessels, tear-ducts, nerves and conduits – that carried the blood, tears and other fluids around the body. According to this belief, obstructions within this system might cause ‘floods’ or ‘droughts’ in different areas of the body, or certain diseases could be eliminated in the excreta. This erroneous concept of bodily functions was probably based on people’s understanding of how Egypt worked as a political and economic unit, dominated by a great central river which irrigated the countryside through a network of canals. It was thought that the metw were all centred on the heart (regarded as the locus of individual personality, thoughts and emotions), and that this organ had a direct impact on various bodily functions. For example, if someone felt sadness in his heart, this was supposed to send tears to his tear-ducts, with the result that he would start to cry.

Treatment of Patients

When Amenmose visited Nefert, he followed the general guidelines laid down for his profession. Doctors were expected to have high ethical standards and to treat the sick in an enlightened and considerate manner. No patient was ever regarded as untouchable; in each case described in the Medical Papyri, the patient’s condition was identified as curable, incurable, or uncertain in outcome, but even when there was no hope of recovery, every consideration was given to alleviating the patient’s pain and discomfort. Doctors were also expected to show exemplary behaviour when they visited patients at home: they were forbidden to stare at women they encountered in the household, and were not allowed to divulge their patients’ confidences.

Nefert’s medical practitioner followed a well-established procedure as he sought to diagnose and treat her condition. First, he examined her physically and asked her about the symptoms she was experiencing; then he diagnosed her ailment and prescribed treatment. In cases where the diagnosis could not be made immediately, a doctor would recommend that the patient remained in bed on an invalid diet for several days, before undertaking a further examination.

The Egyptians had access to surgical and pharmaceutical treatments. Surgery was usually recommended for surface wounds, excision of some tumours, and setting dislocated or fractured bones. The doctors also performed operations such as trepanning and male circumcision, which was widely practised amongst certain sections of the population. However, surgery was not recommended for the ‘Tumours of Khonsu’ (the moon-god), a type of growth regarded as incurable unless the god intervened. Drugs derived from plants such as opium were available as anaesthetics, although it is uncertain when they were first used in Egypt.

Some medical specializations were considered particularly important. There were specialist doctors for eye diseases, which were commonplace; for example, trachoma, a chronic form of conjunctivitis, was probably endemic and a major cause of blindness in ancient Egypt. Blindness is depicted in some tomb-scenes, often in relation to harpists: entry to this profession may have been reserved for blind men in order to provide them with a means of livelihood.

Some Medical Papyri refer to difficulties associated with childbirth and gynaecological problems. They include tests for fertility, pregnancy and determining the sex of an unborn child, as well as contraceptive methods which involved placing various materials and substances, such as honey, ground dates and crocodile excrement, in the vagina.

Pharmaceutical treatments were frequently recommended for many illnesses. The patient took some medicines orally, applied ointments externally, or was treated with fumigation. The medicines incorporated a wide variety of ingredients, which included pulverized minerals and precious stones; herbs, plants and plant extracts; the fat, blood, horns, hides, hooves and bones of various animals; and excrement, urine and aromatic oils. Some treatments used fragrant oils and pleasant substances to attract good deities to help the patient, while in other cases, disagreeable substances were included in the expectation that they would drive out evil. Honey was sometimes given to the patient to ‘sweeten the pill’, and it was recommended that unpleasant ingredients should be swallowed with liquid vehicles such as water, wine, milk and beer.

Other types of remedy were used to ‘transfer’ pain or sickness away from the patient; in one example, a migraine headache was treated by rubbing the patient’s head with a fish-head in the hope that the pain would move into the fish. However, when no physical treatments were available, the physician might resort to a magical spell. In the case of the common cold, for example, the spell was designed to drive the cold out of the patient:

‘Flow forth, fetid nose! Flow forth, son of fetid nose! Flow forth, you who break the bones, destroy the skull, and make ill the seven holes in the head.’ [Papyrus Ebers 763. Author’s translation]

Nefert had endured her symptoms – a severe cough, breathlessness when she exerted herself, and pains in her chest – for many years, but they gradually worsened as she grew older. The Medical Papyri provide various remedies to ‘drive out cough’ – either suppressants which included sweet liquids made from honey, carob and dates, or expectorants (woodworm was the main ingredient of one medicine), which made the cough productive.

Nefert’s symptoms were caused by a disease known today as sand pneumoconiosis.2 This is characterized by severe inflammation and scarring of lung tissue, caused by breathing in fine dust and sand from the atmosphere. The disease is similar to silicosis, a condition observed today in miners and stonemasons, which results from damage to their lungs caused by a lifetime of inhaling coal and stone particles. A major factor in sand pneumoconiosis is exposure to blown sand and sandstorms. These conditions existed in antiquity but are also prevalent in some areas today, with the result that modern populations living in the Sahara and Negev desert suffer a high incidence of sand pneumoconiosis.

Painted wooden anthropoid coffin belonging to Nekht-Ankh. Studies on his mummy showed that he had suffered from several diseases, including sand pneumoconiosis and parasitic infestations. From the Tomb of Two Brothers, Rifeh. Dynasty 12. Manchester Museum.

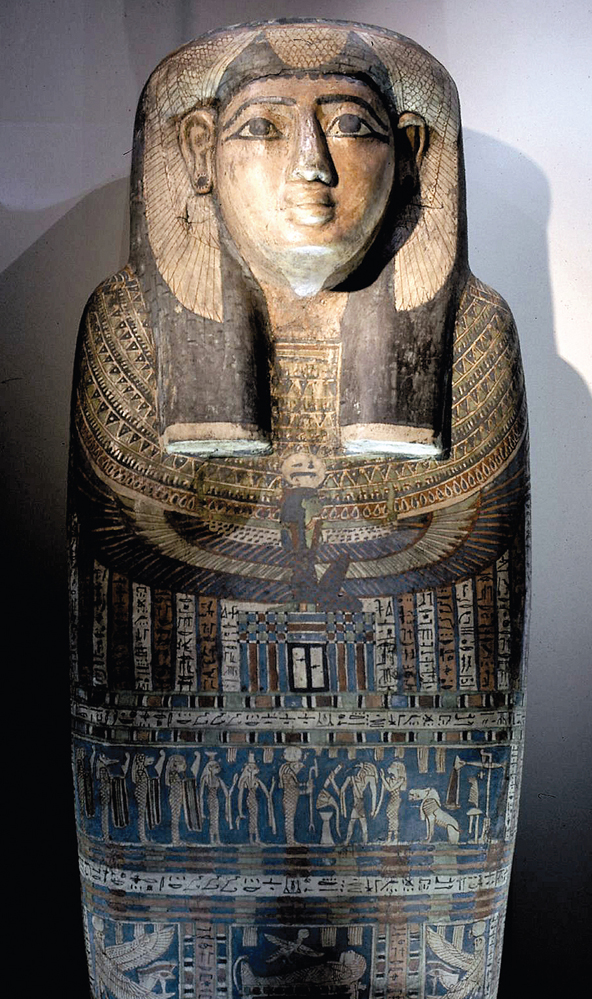

Painted wooden anthropoid coffin of Khnum-Nakht. Studies on his mummy showed evidence of growth arrest in his lower limbs resulting from a period of temporary generalized illness in his youth. From the Tomb of Two Brothers, Rifeh. Dynasty 12. Manchester Museum.

For some years, scientists have been able to use Analytical Electron Microscopy (AEM) to identify silica particles in mummified lung tissue, thus confirming the presence of sand pneumoconiosis in antiquity. Indeed, it is likely that many adults living in ancient Egypt developed this condition as a result of continuing exposure to dust and sand, and consequently suffered serious ill-health from its debilitating symptoms.

Parasitic diseases were another major problem for the ancient Egyptians, and most people, regardless of class or status, would have experienced a variety of chronic and debilitating symptoms from parasitic infestations. Many of these afflictions are described in the Medical Papyri, but although the symptoms associated with these diseases are listed, the texts do not confirm that a specific parasite was responsible for causing a particular infestation. Today, scientists use radiological, histological and immunological techniques to examine the mummies, and can sometimes positively identify the genus of a particular parasite.3

In addition to problems caused by the deterioration of her lungs, Nefert was also afflicted with several parasitic diseases. Unable to identify the specific cause of her problems, the doctors simply tried to treat the symptoms of these conditions. Modern scientific tests would today demonstrate that one infection was caused by the parasite Strongyloides; this worm would have entered Nefert’s body through the skin of her feet when she came into contact with soil that was contaminated with larval forms of the worm. Her symptoms included stomach-ache, diarrhoea, and some blood in the faeces; eventually, when the worms reached her lungs and matured into adult forms, they caused inflammation which led to coughing and wheezing.

Nefert suffered from another parasitic infestation, schistosomiasis or bilharzia, which was caused by a flatworm (a schistosome).4 Three elements are required in order for this parasite to complete its complex lifecycle: two hosts (a human, and a freshwater pulmonate snail), and stretches of stagnant water (lakes, ponds or canals) in which these snails can live. Throughout her life, Nefert had bathed in lakes and ponds on her family’s country estate, and in her youth she had been infected by larval forms of a type of worm, Schistosoma haematobium, which inhabits the veins of the bladder area. These parasites eventually matured into adult worms inside her body, and the male and female worms paired. The female then laid eggs, and some became trapped and were retained inside Nefert’s body, causing frequent urination, tenderness of the bladder, and blood in the urine. This disease can vary in its intensity, depending on the number of retained eggs and the reaction of the body to their presence. Nefert’s infection was relatively light, but she still experienced a degree of chronic ill health and debility throughout her life.

Painted wooden coffin of Asru. She was a Chantress in the Temple of Amun at Karnak. The horizontal scene on the front of the coffin shows the scene of Weighing the Heart’. Probably from Thebes. Late Period. Manchester Museum.

Mummy of Asru. Scientific studies show that she suffered from a range of diseases including an infection caused by the parasite Strongyloides. However, her estimated age at death, between fifty and sixty exceeded the normal lifespan of forty years. Probably from Thebes. Late Period. Manchester Museum.

None of the medicines that Nefert’s doctors prescribed had much effect on the course or outcome of her afflictions, and like so many Egyptians she suffered a substandard level of health for most of her life. The medicinal ingredients in these remedies included herbs, plants, fruit, berries, various minerals such as salt, natron and malachite, and animal products (ox and goose fat, oil and honey).

Nefert and other adult members of the family also suffered from dental problems. Caries [tooth decay] was not widespread in Egypt before the Graeco-Roman Period; in pharaonic times, the main dental problems were the result of severe wear [attrition] on the grinding and biting surfaces of the teeth.5

This condition frequently led to deterioration of the teeth and gums. Attrition was mainly caused by the bread which the Egyptians ate in large quantities. Samples placed in the tombs for the owner to consume in the afterlife have been scientifically analyzed and subjected to radiological and microscopic studies, and these have revealed the presence of high levels of mineral particles. Small fragments of sand and stone contaminated the bread at different stages of its production: these included windblown sand, debris that entered from the soil, and material that infiltrated during the grinding process or when the grain was stored.

Even in childhood, the bread caused some damage to the teeth, but the problem became exacerbated throughout adolescence and adulthood. The diet of gritty bread wore down the cusps of the teeth, and if secondary dentine was not deposited in the pulp chamber faster than the wear occurred, the body of the tooth could become affected, resulting in an apical abscess. This led to a pocket of infection which caused general debility and lowered resistance to disease, in some cases even resulting in death. However, despite widespread dental problems, there is no convincing evidence that specialist dentists existed.

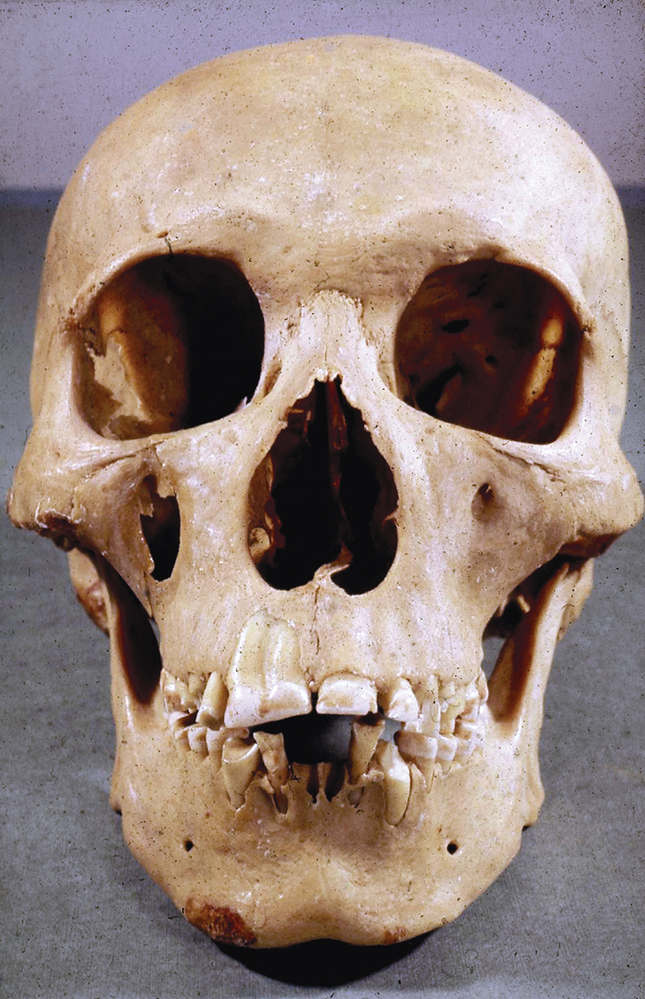

Mandible of Khnum-Nakht, showing attrition (severe wear) on the biting surfaces of the teeth. This was caused by sand and grit in the bread. From the Tomb of Two Brothers, Rifeh. Dynasty 12. Manchester Museum.

Dental techniques were probably no more advanced than extracting teeth; modern examination of skulls and dentitions has demonstrated a high incidence of abscesses and other dental problems which seem to indicate that professional help was probably not available, and that many people suffered painful and distressing conditions.

Temples as Medical Centres

Famous centres of medical science and healing existed in Greek temples at Epidauros and on the island of Kos, where Hippocrates, the ‘father of medicine’, was born in c.460 BCE. He established a purely scientific basis for medical theory and practice, replacing the ideas of earlier Greek physicians who had relied largely on traditional methods and faith-healing, which functioned around the cult of the god Asklepios. It is also known that during the Graeco-Roman Period, Egyptian temples at Memphis, Denderah and Deir el-Bahri were renowned as centres of medical healing. One Classical writer, Diodorus Siculus, attributed the idea of healing dreams to the Egyptian goddess Isis, and it appears that the Egyptian temples had a long tradition of healing.

Skull of Khnum-Nakht, showing a rare developmental abnormality of the left upper-central tooth and a supernumerary tooth; this condition is known as double gemination or fusion of the teeth From the Tomb of Two Brothers, Rifeh. Dynasty 12. Manchester Museum.

Although no archaeological evidence of this earlier tradition has yet been found, texts dating back to the Middle Kingdom (c.1900 BCE) refer to Sais and Heliopolis as famous religious healing centres. Inscriptions also state that the Persian king, Darius, who ruled Egypt in c.500 BCE, ordered the reorganization of the medical school at Sais. We can therefore assume that medical knowledge and the treatment of patients were important functions of several temples during the pharaonic period, and that the Egyptian physicians were the first to care for patients within an institutionalized, religious context.

There is ample evidence during the Graeco-Roman Period that temple healers used isolation and therapy as forms of treatment, and that they were credited with miraculous cures. The temples at Deir el-Bahri and Denderah are of particular interest. Two ancient Egyptian sages became patrons of healing at Deir el-Bahri: these were Imhotep, credited as the founder of medical science, and Amenhotep, son of Hapu, a wise and learned man who lived at Thebes in the New Kingdom. Deir el-Bahri became a centre of healing where many visitors came to seek cures; some painted or scratched their names on the walls of a colonnaded upper terrace where patients sat out in the open air. Sometimes these describe how healing occurred: for example, a Macedonian ‘hired hand’ named Andromachos records that the god cured him as soon as he arrived at the temple. The physician Zoilos visited the temple in the second century CE, perhaps to observe how the priests treated their patients so successfully.

At Denderah, archaeologists have discovered a very interesting mudbrick building which stands adjacent to the Temple of Hathor. When first excavated, one Egyptologist tentatively identified it as the temple’s ‘House of Life’, but it is now considered to be a medical centre or ‘sanatorium’. It was arranged around a colonnaded court which gave access to other rooms; although probably of Graeco-Roman date, it may incorporate earlier structures.

Sacred water was an essential element in conveying the life-force of the god Osiris to temple patients, and played an important part in various medical treatments such as bathing patients’ bodies, feet, or limbs, and in the use of healing statues. Part of an inscription dedicated to Osiris, identifying him as the water of life, was found in the sanatorium; such texts usually appear on the bases of healing statues which were probably once an important feature of the original building at Denderah. Statues played a significant role in treating the sick: water was directed over the statue base so that it could absorb the magical, curative properties of the text, and was then channelled into the treatment cubicles where patients received its life-giving benefits.

The ‘Sanatorium’ (foreground) at the Temple of Hathor, Denderah. This mudbrick building incorporates a series of cubicles where the patients were bathed with sacred water. Late Period/Graeco-Roman Period.

The sanatorium at Denderah specialized in treating patients suffering from mental illness, preparing them for temple incubation (the ‘Therapeutic Dream’). Although most evidence for this procedure dates to the Graeco-Roman Period, the system had existed in Egypt from at least the Middle Kingdom (c.1900 BCE). Isolated in a silent, darkened room lit by lamps and perfumed with the aroma of burnt wood, the patient was induced into a dreamlike state which transported his soul to ‘Nun’, the great primaeval ocean from which life had emerged and where the dead lived.

This state of deep sleep lasted a couple of nights, and allowed the patient to use spells to make contact with the gods. He could ask about his future and any dangers or evils that awaited him, and could petition the deities to cure his illness. Singing was regarded as a particularly effective method of driving away mental illness: the earliest known reference occurs in the Papyrus of Merikare (c.2200 BCE), where the goddess healed the patient directly through song. Hundreds of years later, it was claimed that Isis-Hathor, the resident goddess of Denderah, would sometimes intervene, appearing to the patient and holding him; as divine inventor of the most efficacious healing formulae, she was able to drive away the patient’s affliction with her sacred songs. Isis had this ability because she had personally attained immortality, and could even restore to full health those who had given up any hope of a cure. In other cases, divine treatment would be handed down to the patient indirectly through the words and interpretation of a priest. The Egyptians firmly believed that this trance-like state gave the patient a unique opportunity to receive divine healing and unravel and resolve their personal problems.

Gods of Healing

No one specific deity presided over medicine and healing; instead, various gods held responsibility for different areas of medicine. Sekhmet, patron of the most senior priest-doctors, and her consort, Seth, were both regarded as destroyers who brought epidemics, and were worshipped and petitioned in the hope of averting these plagues. Ibis-headed Thoth, god of scribes and learning, was honoured as the inventor of healing formulae and divine author of medical texts. Isis-Hathor was another important healer; according to mythology, she had reassembled the scattered limbs of her husband Osiris and, through her knowledge of magic, had brought about his resurrection: this enabled her to take on the role of patroness of magicians. Horus and Amun possessed special powers to cure eye diseases, and Tauert, represented as an upstanding, pregnant hippopotamus, with influence over all aspects of fecundity and childbirth, received the special prayers offered up by women in their homes. Wise men such as Imhotep and Amenhotep, son of Hapu, were also credited with special curative powers, and Imhotep was widely worshipped as a god of medicine.

Medical Sources

No single description of medical science in ancient Egypt has ever been found. Information comes from several sources: scenes and statuary showing people with various afflictions; tombstones (stelae) of physicians which list their titles and provide some idea of specialization and career progression; surgical instruments (although the only examples found to date are from the Graeco-Roman Period); and a wall-scene from the Temple of Kom Ombo which may depict a set of surgical instruments. Also, scientific techniques can be used to detect evidence of disease and disease patterns, thus providing a clearer picture of the Egyptians’ state of health and living conditions.

The ten major Medical Papyri that have been identified to date are perhaps the most important source of evidence about disease and treatment in ancient Egypt.6 These carry the names of their modern owners (Edwin Smith, Chester Beatty, Carlsberg and Hearst); the towns where they are kept in museum collections (London, Leyden and Berlin); or the ancient sites where they were discovered (Kahun and the Ramesseum). The Ebers Papyrus is called after its modern editor. Most of these papyri date from c.1550 BCE, but they are all probably copies of earlier works, and the total must represent only a minute proportion of the medical texts that once existed in ancient Egypt. Each document contains a wide range of subject matter, and it is evident that the contents were not brought together to form any consistent or coherent group of material.

Dr Margaret Murray (second right) and members of her team unwrap and autopsy the mummy of Khnum-Nakht at the University of Manchester on 7 May 1908. Manchester Museum.

Drs Rosalie David (right) and Edmund Tapp unwrap and autopsy Mummy 1770 from the Manchester Museum collection, in June 1975. Copyright of The University of Manchester.

Two documents are devoted to specific areas of medical practice: the Edwin Smith Papyrus is the world’s earliest extant treatise on surgery, while the Kahun Papyrus provides the first record of gynaecological treatments, contraception, and fertility and pregnancy tests. However, other papyri contain a mixture of subject matter, and appear to have been composed for a variety of purposes. Some examples were probably used as handbooks by practising physicians, whereas others may have been instructors’ outlines for medical lectures, or students’ lecture notes and clinical notebooks, which they kept as a record of the training they had received in medicine and surgery. Some documents may have had more than one use: perhaps originally written as a student’s notebook, the owner perhaps retained it once he qualified as a doctor, and continued to consult it as a reference work.

Even such a small sample of texts demonstrates the great variety of Egyptian medicine; their differences are probably explained by the fact that they come from very disparate contexts. For example, the Kahun Papyrus, which deals with social medicine, was discovered in a town archive, while the Hearst Papyrus, which lists drug treatments, may have belonged to a village doctor. Other documents, which take a more didactic approach, describing the principles behind the organ-system of the human body, may have formed part of a temple archive. Case studies, a key feature of most of the documents, provide information about symptoms, diagnoses, and recommended treatments. Most of the papyri discuss scientific treatments alongside magical formulae, although the number and proportion of these ‘rational’ and ‘irrational’ methods varies considerably in different documents.

Many of the medical texts were probably produced in the ‘House of Life’, where scribes copied texts from earlier editions on to papyrus scrolls; however, because they did not always have specialized knowledge and training in medicine, they sometimes made mistakes. Some papyri have evidently been compiled from smaller collections of prescriptions and treatments; these may have been handed down orally or in writing before they were brought together by a physician or priest for his own use or for the instruction of other doctors.

Generally, this group of documents demonstrates that the structure and practice of pharaonic medicine was complex. Some procedures, based on acute observation of the patient’s condition, were effective, but many had little or no scientific value. Although medical practitioners would have shown kindness and respect to Nefert and her counterparts, there is little hope that most of the prescribed treatments would have either improved their health or extended life expectancy.