Military Campaigns

In our imaginary family, Khary’s second son, Amenemhet, was a soldier who fought in the campaigns of Tuthmosis III. After they expelled the foreign rulers (the Hyksos) from Egypt, the kings of Dynasty 18 became aware of a need for a national army. Prior to this, there had been no standing army: whenever the king decided to fight or launch campaigns, his district governors simply conscripted peasants from the local population. However, the kings now recognized the need to maintain a standing army so that they could foil any future attempted invasions. The earliest rulers of Dynasty 18 therefore set out to organize an army on a national basis, manned by officers who were professional soldiers.1

This standing army was probably started by King Amosis I. He and his immediate predecessors had successfully driven the Hyksos from Egypt, and he completed the task by pushing them back into southern Palestine where he finally subdued them so that they could not regroup and return to Egypt. He also dealt with an insurrection in Nubia. With Egypt’s northern and southern borders secured, Amosis I’s successors were now ready to conquer foreign lands and establish an Egyptian empire.

Some evidence about military expeditions and campaigns comes from scenes and inscriptions on tomb and temple walls. The most significant account of the expulsion of the Hyksos is preserved in an autobiographical account inscribed on the walls of the tomb of Ahmose, son of Ebana, at El Kab. The text relates events in the life and career of Ahmose, a professional soldier who fought against the Hyksos and was rewarded by the king. Following this, he accompanied the king to Sharuhen in Palestine, where again the army was successful:

‘Then Sharuhen was besieged for three years. His Majesty despoiled it and I brought booty away from it: two women and a hand [i.e., the hand of a slaughtered captive]. Then the gold of favour [i.e., a royal reward] was awarded to me, and my captives were given to me as slaves.’ (The Autobiography of Ahmose, Son of Ebana. Author’s translation)

This inscription also provides information about Ahmose’s illustrious career: at first, he served on board a ship, but when King Amosis became aware of his ability, he had him transferred to take part in military action against the Hyksos:

‘Now when I had established a household [that is, he had married], I was taken to the ship ‘Northern’ on account of my bravery. I followed the ruler on foot when he rode around in his chariot. When the town of Avaris was besieged, I fought bravely on foot in His Majesty’s presence.’ (The Autobiography of Ahmose, Son of Ebana. Author’s translation)

Once the Hyksos problem had been resolved, Ahmose accompanied the king to Nubia on a campaign to put down a local insurrection. He continued his career under the kings who succeeded Amosis I – Amenhotep I and Tuthmosis I – and took part in these rulers’ Nubian campaigns to subdue local rebellions. Finally, he accompanied Tuthmosis I’s campaign to the River Euphrates in northern Syria, a military action which was part of Egypt’s new strategy to establish an empire.

Ahmose was rewarded with promotion to the rank of ‘Commander of the Crew’, and received a royal gift of land in his hometown of El Kab. His career was typical of the new professional soldier: promoted from the ranks, he spent his whole life in the armed forces, serving a succession of rulers. Ultimately, the king rewarded his loyalty and ability with a high-level position and considerable wealth, which he was able to pass on to his family. His grandson, Paheri, eventually built the best tomb at El Kab, and became mayor of two towns.

In the early part of Dynasty 18, Egyptian rulers were primarily concerned with establishing their power in Syria/Palestine.2 At the beginning of this dynasty, ethnic movements in the Near East had created a power vacuum, and a new kingdom – Mitanni – had established itself in the land of Naharin, situated between the rivers Tigris and Euphrates. The population of Mitanni consisted of a ruling aristocracy of Indo-Aryan origin, and the Hurrians – people who had branched out in c.2300 BCE from their original homeland situated south of the Caspian Sea.

The Mitannians were one of the most powerful enemies that Egypt faced in Dynasty 18, although eventually the two countries became allies. The Egyptians wanted to set their own northern boundary at the Euphrates, so when Mitanni first began to push southwards, this led to direct conflict. Northern Syria became the main focus of Egypt’s campaigns and the most significant arena of warfare. However, the princedoms and city-states which occupied Palestine and the rest of Syria at this time were also drawn into the conflict; although they presented no cohesive threat to Egypt or Mitanni, both sides tried to coerce them into becoming vassal states.

Amenhotep I left no record of his military activities in this area, although he may have taken preliminary actions which laid the foundations for Tuthmosis I’s new, aggressive policy. Tuthmosis I, the first Egyptian king to launch a major offensive in Syria, led an expedition across the Euphrates into Naharin, where he set up a commemorative stela. His army killed many of the enemy and took others as prisoners before it returned home through Syria, where the king celebrated his success by organizing an elephant hunt at Niy. Wall inscriptions in tombs at El Kab belonging to Ahmose, and a relative, Ahmose Pennekheb, provide details of the roles these men played in the campaign.

Tuthmosis I also fought in Nubia, extending Egypt’s power as far as the region of the Fourth Cataract, where he built new fortresses.3 He established control over an area that stretched from this part of Nubia to the Euphrates in the north – the ultimate limits of Egypt’s empire. His policies were continued by his son, Tuthmosis II, who campaigned in Palestine and overthrew a rebellion in Nubia, but it was his grandson, Tuthmosis III, who ensured that Egypt became the greatest military power in the region.

Since Tuthmosis III acceded to the throne as a minor, his stepmother Hatshepsut had the opportunity to seize power and, for a time, she ruled in his stead. During Hatshepsut’s reign, some city-states in Syria/Palestine had formed alliances with the Mitannians, while others declared themselves independent of Egypt’s influence. However, once Tuthmosis III established himself on the throne, he wasted no time in reasserting Egypt’s supremacy. In Year 23 (the first year of his independent reign), he mounted a campaign against Mitanni and a coalition of city-states led by the Prince of Kadesh, a city on the River Orontes. The Egyptian armies were able to capture the city of Megiddo, a victory which formed the basis for future expansion in Syria/Palestine.4

Tuthmosis III sent a further sixteen campaigns to Syria over the next twenty years, which successfully sacked the city of Kadesh twice,5 and crossed the Euphrates to penetrate deep into Naharin. In the eighth campaign, which took place in Year 33, the Egyptians resoundingly defeated the Mitannians, but despite some significant successes there was no outright winner in this contest and, ultimately, the two powers were forced to recognize that neither would ever win a conclusive victory. Therefore, towards the end of Dynasty 18, they changed their policies and became allies. Tuthmosis III also reasserted Egypt’s control of Nubia, leading campaigns as far south as the Fourth Cataract. His excellent strategies and well-executed campaigns ensured that he is now appropriately recognized as Egypt’s greatest military ruler.

Wall inscriptions in some temples preserve historical accounts of military exploits undertaken by kings of the New Kingdom.6 However, these often provide propagandist versions of events, their main aim being to record the pharaoh’s glory and battle prowess.7,8 The campaigns of Tuthmosis III are described in wall-scenes and inscriptions found in the Temple of Karnak,9 and on two stelae: one comes from Armant, and the other was set up in the king’s temple at Napata (Gebel Barkal), near the Fourth Cataract. Taken together, these literary sources provide sufficient information for Egyptologists to reconstruct some events in Tuthmosis III’s campaigns.

One of the Karnak records, carved on the walls of two halls situated behind the Sixth Pylon in the temple, is known as The Annals. These provided a factual account of Tuthmosis III’s annual campaigns; they give most information about the first one, and the others are recounted more briefly. Another inscriptional source, the so-called Poetical Stela of Tuthmosis III, was placed in a court in the same temple. This hymn of triumph, written in terms of a speech given by the god Amen-Re, also recounts the king’s victories.

According to these sources, the king’s campaigns were all successful. The Annals relate how his first campaign was undertaken in the fourth month of winter; he set out through Palestine, and by the first month of summer had reached Gaza. He took this city and then marched to Megiddo where a group of princes, led by the ruler of the city of Kadesh, awaited him. Through his own great personal valour and clever tactics, the king achieved victory and the enemy was routed, but this was followed by a seven-month siege of Megiddo. The Annals go on to describe the preparations his army took before attacking the city.

An important feature of Tuthmosis III’s military strategy was subjugation and provisioning of harbours along the Palestine/Syria coast; this was undertaken in order to support his campaigns in the hinterland.8 The inscriptions relate that, in the sixth campaign, some of the Egyptian forces were transported by ship to the Palestine/Syria coastal area. In the seventh campaign, Tuthmosis III sailed along the coastal cities, proceeding from one harbour to the next; he subdued and equipped them with provisions which would support his army’s actions in the hinterland. Inspecting and supplying the harbours became a regular feature of Egyptian warfare.

Tuthmosis III’s eighth campaign, which he undertook in Year 33, made use of boats to cross the River Euphrates and defeat the Mitannians. According to the Gebel Barkal Stela, these vessels were built every year at Byblos. They formed part of the annual tribute that Byblos, a vassal-city, paid to Egypt. These measures ensured that Egypt, although deficient in its native wood supplies, was still able to build up an adequate fleet. However, on the eighth campaign, the boats were not sent by sea from Byblos to Egypt; instead, they were transported overland to the Euphrates on wheeled wagons drawn by oxen.

Wooden Royal Boat. Dismantled into many pieces, this boat was discovered in a pit south of the Great Pyramid, and was then painstakingly reassembled over a period of forty years. It may have been used once at the king’s funeral, or was possibly a symbolic boat in which the deceased ruler could sail around the heavens. From Giza, now displayed there in the Solar Boat Museum. Dynasty 4.

The Egyptians became the greatest military power in the region during the New Kingdom. Their empire was the first to be established there, although it was much smaller than the later Assyrian and Persian empires. The Egyptians had always pursued a policy of colonization in Nubia, and by the New Kingdom, this region was effectively ruled as part of Egypt. However, circumstances in areas to the north of Egypt were different, and although the Egyptians had conquered many of the city-states there, they decided to leave local governors in control of their own cities, provided that they gave allegiance to Egypt. This arrangement made it unnecessary for the Egyptians to establish any centralized system of administration to control the region.

Egypt became a wealthy, powerful and cosmopolitan state during the New Kingdom. Gifts from other great nations, tribute from vassal states, and booty and prisoners-of-war brought back from the military campaigns all added to the country’s status. The Poetical Stela of Tuthmosis III emphasizes the crucial role played by Amen-Re in ensuring Egyptian victories and, to demonstrate their gratitude, the kings donated booty and prisoners-of-war to the god’s temple at Karnak.

Organization of the Army

Amenemhet was trained from youth in a military school to prepare him for a career as a professional soldier and member of the chariotry. Training included exercises such as wrestling movements and holds depicted in tomb-scenes at Beni Hasan; he also learnt horsemanship.

The field army was split into divisions; each division, which consisted of infantry and chariotry and numbered about 5,000 men, carried the name of a major god and was commanded by the pharaoh or one of the princes. The king was commander-in-chief of the army and led the troops in major campaigns, but minor expeditions were usually headed by princes or officials. In addition to all his other duties, the First Minister was also Minister of War; he and the king regularly consulted the Army Council (which included senior officials and advisors) about military strategy and tactics.

Major sources of information about the army and warfare include reliefs and inscriptions placed on buildings in the capital city of Tell el-Amarna and on the walls of temples at Abydos, Beit el-Wali, the Ramesseum, Karnak and Abu Simbel. These refer to great campaigns undertaken in Dynasties 18 and 19. Other evidence comes from surviving weapons, scenes in the Theban tombs of Kenamun and Hapu, reliefs on the chariot of Tuthmosis IV, paintings on the lid of a wooden chest belonging to Tutankhamun, and chariots found in the Theban tombs of Userhet, Yuya and Tuthmosis IV. In addition, the Edict of Horemheb provides information about reorganization of the army that took place at the end of Dynasty 18. According to this Edict, when the army was in Egypt it was divided into two corps – one based in Upper Egypt, the other in Lower Egypt. Each was led by a lieutenant-commander, responsible to the general; duties included garrisoning the frontier forts, escorting royal processions and public celebrations, dealing with riots, and supplying the unskilled labour for public building projects.

The chariotry10 was probably introduced during the Hyksos Period. It was divided into squadrons which each had twenty-five chariots. The ‘Charioteer of the Residence’ was commander of the chariotry, which was probably divided into two sections – light and heavy troops – who were both armed with bows. The main duty of the light troops was to shoot missiles into the enemy ranks, while the heavy fighters were expected to break into the enemy’s massed infantry.

The Hyksos probably introduced the chariot to Egypt from Palestine. Chariots from both these regions were of a similar design, and Egyptian words for ‘horse’, ‘chariot’, and associated trappings were probably adopted from Indo-Aryan terms. The chariots had frames of pliable wood which were covered in leather decorated with metal and leather binding. The back of the chariot was open, and the sides were largely cut away. The earliest examples had two four-spoke wheels but, by the reign of Tuthmosis IV, these were replaced by six-spoke or, more rarely, eight-spoke wheels. All chariots seem to have been drawn by a maximum of two horses: no representations have been found of chariots being pulled by a greater number of animals.

Each vehicle held two men – a driver and a fighting soldier who carried bows and arrows, a javelin, shield and sword. In the temple scenes, the king is often shown alone in his chariot, although in reality, he was probably usually driven by a courtier of very high status known as the ‘First Charioteer of His Majesty’. This man was also periodically sent on foreign missions, perhaps to acquire stud horses. A royal stable-master supervised the stables where the horses were trained to take the chariots; other stable masters of lower rank were employed to feed and exercise the animals.

Although wealthy people who owned horses probably rode them on their own estates, there are no art representations from the New Kingdom showing the cavalry (soldiers riding horses into battle), perhaps because the horses were not large or strong enough for this purpose. However, it is recorded that Tuthmosis III captured horses during his campaigns in Syria/Palestine and these were probably transported to Egypt to increase and improve the bloodstock.

The infantry was Egypt’s original fighting force. During the Middle Kingdom, this consisted of two main divisions – older foot soldiers, and the younger, less experienced men. By the New Kingdom, this had increased to three groups – recruits, trained men, and specialized troops. The infantry, divided into regiments according to the arms that they carried, included bowmen, spearmen, swordsmen, clubmen, and slingers. Bowmen provided a major force of the army, fighting in both the chariotry and the infantry. Each division of an infantry regiment had its own standard, which became a rallying point during battle.

From the titles held by the soldiers, we can assume that the lowest commander was known as the ‘Greatest of 50’. The next in line – the ‘Standard-bearer’ – was in charge of 200 men, while a higher-ranking officer supervised 250 soldiers. Next, there was the ‘Captain of the Troop’, and then came the ‘Commander of the Troop’, whose duties may have included heading a brigade or several regiments, or commanding a fortress. His superior, the ‘Overseer of Garrison Troops’, was responsible to one of two ‘Overseers of Fortresses’; they supervised the Nubian border and the Mediterranean coast. Next in rank came the ‘Lieutenant-Commander’, who combined the duties of a senior officer, general administrator, and military commander. He was responsible to the General (‘Overseer of the Army’), who answered to the king. In many instances, the rank of general was held by a prince, who commanded a wing or division in battle.

The army also appears to have had some specialized troops. An elite fighting force known as the ‘Braves of the King’ was trained to take charge of attacks. The ’w’yt were garrison troops who served at home or abroad; one of their duties was to protect the king and the royal household. The ‘Retainers’ may have started out as the Royal Bodyguard, but in later times their role was to issue rations to troops and act as letter-carriers.

An extensive support system assembled and administered the army’s supplies at home and on foreign campaigns. This was supervised by military scribes: when the army was campaigning abroad, they acquired any necessary supplies en route from local governors, and also listed booty taken in battle. In addition, they organized the army’s transport system of pack-asses and ox-drawn wagons; these animals accompanied the army and were sometimes used alongside each other.

When a professional army was first established in the New Kingdom, some men from wealthy families chose to become professional fighters, but most soldiers were still conscripted from the peasants. However, the Egyptians were not a naturally warlike people; they preferred to remain at home with their families, and did not wish to die in a foreign country where the correct burial procedures would not be followed, thus jeopardizing their chances of eternal life. Therefore, the State had to provide incentives for men to join and remain in the army: they had the opportunity to seize booty on campaigns, and royal land gifted to professional soldiers could only be inherited by their sons if they also joined the army.

However, even these measures were insufficient to establish an army that was strong enough to build and retain an empire, and so the kings had to employ other methods. By Ramesses III’s reign in Dynasty 20, one in ten males amongst the native population was conscripted for military service. Also, nations or groups of people whom the Egyptians had conquered or made their allies began to provide mercenary troops for the army. For example, in Dynasty 18, some soldiers were recruited from Nubia, and Amenhotep III also started to enlist prisoners-of-war as soldiers, a practice which continued until the Ramesside Period. In later times, foreign recruits formed a substantial and significant part of the Egyptian army. They fought alongside Egyptian soldiers on campaigns to invade other lands and suppress rebellions, and sometimes undertook garrison duty in Egypt when native troops were absent on expeditions. Mercenaries were allowed to retain their own battledress and weapons, but do not appear to have received gifts of land in exchange for their services: they were simply paid as hired soldiers.

Weapons and Warfare

Weapons have survived in some tombs, and are also depicted in wall-scenes in tombs and temples. Soldiers’ equipment included both offensive and defensive weapons. There were wooden bows, strung with catgut, and the composite bow, introduced to Egypt from Palestine during the Hyksos Period, which is depicted in reliefs on the chariot of Tuthmosis IV, where it is shown in the hands of both the king and his enemies. Arrows made of wood or reeds and tipped with metal or stone were carried in a large quiver.

Other offensive weapons included metal and wooden maces, curved sticks, spears which consisted of a metal shaft inserted into a wooden handle, and javelins which had a two-edged metal head. There were also leather or string slings, daggers and knives, and short, straight swords which often had a double edge tapering to a sharp point. Both officers and soldiers in the heavy and light troops were equipped with the khepresh (sickle-sword). This weapon, which had a bronze blade, was probably introduced to Egypt from Palestine during the Hyksos Period; by the New Kingdom, it was more widely used in the Egyptian army than the conventional sword.

Soldiers also carried a fixed-blade pole-axe, and a small axe with a single blade which resembled the tool that carpenters employed to cut up timbers. This axe, which was wielded in close-combat fighting and to attack the gates of fortified towns, exemplifies the Egyptians’ conservative approach to weaponry. They generally favoured traditional weapons of proven ability: for example, while contemporary armies had already introduced the socket-type axe, the Egyptians continued to use the tang-type axe, although the design was gradually changed so that the blade became shorter and had a narrower edge. This type of weapon appears in the hands of infantrymen depicted on the lid of a wooden chest found in the tomb of Tutankhamun; also, a wall-relief at Karnak shows that it was used later by Ramesses II’s soldiers.

The Egyptians’ defensive equipment included thick, heavily padded helmets, coats-of-armour, and large shields. The coats-of-armour, probably introduced during the Hyksos Period, were made entirely of metal bands or were quilted and had metal bands attached. Even by the middle of Dynasty 18, these coats were rare, expensive items, although they were more widely used in later times. Shields, made of wood, covered with leather, and sometimes strengthened with metal rims, offered another form of protection.

The Navy

Essentially an extension of the army, the main role of the Egyptian navy was to transport troops and supplies over long distances, although it occasionally became engaged in active warfare.11 In effect, sailors were ‘soldiers at sea’ rather than a separate force, and it was even possible for a man to be transferred or promoted from one Service to another. Naval recruits (w’w) were often drawn from military families, and usually served on warships, being assigned first to training-crews of rowers supervised by a Standard-bearer, before they joined the crew of a ship. Once part of a crew, recruits were directed by a ‘Commander of Rowers’; he answered to a ‘Standard-bearer’ who was responsible to the ‘Commander of Troops’, which was perhaps a land position rather than an active naval role. At the highest levels, the Admirals took their orders from the ‘Commander-in-Chief’ (a prince) who reported to the king. Ships’ navigation appears to have been organized under a separate chain of command, remaining the responsibility of the Captain and the Captain’s mates. In the navy, it was possible to be promoted either to a higher rank or to a larger ship, or to be transferred to an army regiment. Indeed, in some inscriptions it is unclear whether a title refers to a ship or a regiment.

During Dynasty 18, the navy played an important role as a support service for the military campaigns to Syria, but in the reign of Ramesses III, it apparently became an active fighting force, helping to repel the raiders who attacked the Egyptian Delta.12, 13

In peacetime, the navy helped to develop trading links: in the New Kingdom, Egyptians not only developed naval dockyards along the Syria/Palestine coast, but also established an important naval base, Perw-nefer, probably located in the vicinity of Memphis. Perw-nefer became the country’s chief port in the reigns of Tuthmosis III and his son, Amenhotep II, and the naval base from which ships set sail during their Syrian campaigns.

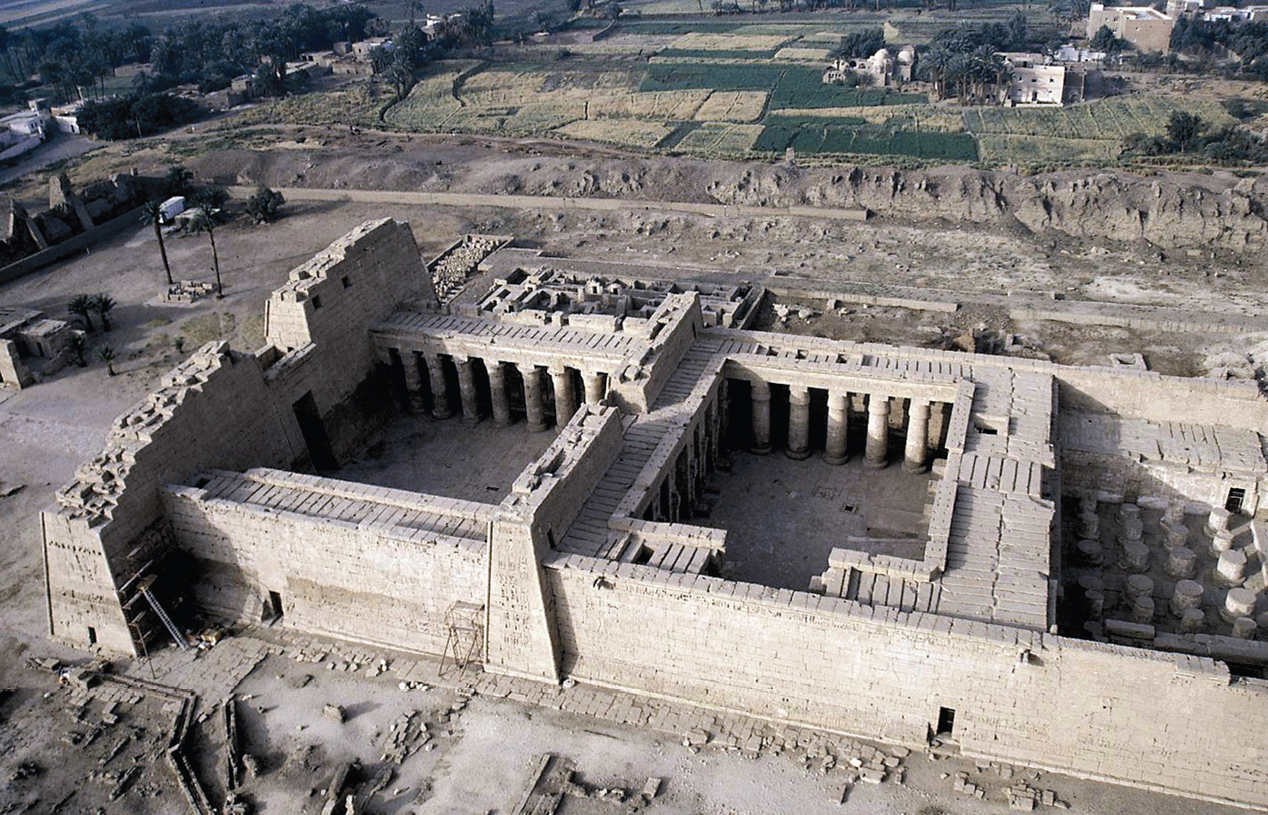

Temple at Medinet Habu, Thebes. This shows a typical temple, with two open courts (left) leading into the hypostyle hall (once roofed). Temple wall-scenes at Medinet Habu show sea-battles fought by the Egyptians against the Libyans and the ‘Sea-peoples’. New.’ Kingdom.

The ships which the ancient Egyptians used for long distance travel have been the subject of much discussion.14,15 During the New Kingdom, it is known that the navy possessed so-called ‘Byblos ships’ and ‘Keftiu ships’; however, scholars are uncertain whether Byblos ships were given this name because they were specially built to travel to Byblos, or because they were constructed in the harbours of Byblos and other Syrian coastal towns. There is one suggestion that, after they captured enemy ships during Tuthmosis III’s Syrian campaigns, the Egyptians used these vessels as prototypes for building their own fleet. However, they had been sending naval expeditions to Punt long before this date, and, as experienced seafarers, already possessed and knew how to sail large, impressive ships. Therefore, it is more likely that the term ‘Byblos ship’ applies to the vessel’s destination port rather than to the place where it was built.

As a professional soldier, Amenemhet regularly participated in Tuthmosis III’s campaigns. Troops conscripted from all the provinces came together at the start of each campaign to slaughter animals and offer them as sacrifices to the gods. Then, as orders were given for the march to start, the troops were summoned with the sound of trumpets.

As a member of the chariotry, Amenemhet played an important role in the army and had experienced many different types of warfare during his long career. Battlefield tactics required that the chariots, led by the king who rode at their centre, were preceded and followed by the infantry. Once the trumpets had signalled the troops to start an attack, the archers sent their arrows into the enemy ranks; then, the chariotry charged forward to flank the infantry who, protected by their own heavy shields, pressed ahead into the centre of the enemy’s forces. Throughout this onslaught, the archers continued to discharge their weapons, causing havoc amongst the enemy. After a successful engagement, the hands and sometimes the penises of the slain were cut off and counted in front of the King or General, so that the number of dead enemies could be calculated. All members of the enemy who begged for mercy and laid down their arms were taken prisoner. Eventually, supervised at the rear of the army, these prisoners would be escorted back to Egypt where they would be allocated to work on building sites or as domestic servants.

In the meantime, enemy possessions were divided up amongst the Egyptian soldiers as their battlefield share of the spoils. This booty, which included arms, horses and chariots, was sometimes laid out in an open area surrounded by a temporarily-constructed wall.

Amenemhet had also taken part in sieges, when the army attacked towns which were often fortified with thick mudbrick walls interspersed by square towers. The main objective of this type of warfare was to keep the attacker as far away as possible from the main wall, and this was sometimes achieved by building an outer circuit wall. The attackers would have to breach this wall first, and when they were in this vulnerable position, it was easier for the besieged townspeople to bombard them with missiles.

Nevertheless, the Egyptians were frequently victorious in these situations, advancing under the protection of their bowmen’s arrows, and then using scaling ladders to climb over the walls or force entry through the gates.

Wall-relief in the Great Temple of Ramesses II at Abu Simbel showing bound prisoners taken captive by the Egyptian army. Prisoners from different geographical areas are distinguished by their facial features and headdresses. Dynasty 19.

Egyptian troops were accommodated in field encampments during their campaigns. The encampment was arranged in a square formation with the main entrance located in one side; Amenemhet and other senior officers, including the General, had tents at the centre of this area while the space towards the outer part of the enclosure was used for feeding the horses and pack-animals, and storing chariots and baggage.

Occasionally, the stresses of campaigning gave rise to insubordination, and some soldiers even deserted. These were not regarded as capital offences: the soldier was simply rebuked by his peers, and was expected to show renewed valour and bravery so that he could be reinstated. However, there was severe punishment for those who revealed military secrets to the enemy, and their tongues were cut out.

When Amenmehet and his comrades returned from the Syrian campaigns, they were greeted along the way by people living in towns that owed allegiance to Egypt: men and women ran from their homes, calling out greetings to the king and his troops. Upon reaching the Egyptian capital, the soldiers received further rewards, and attended a thanksgiving ceremony in the Temple of Karnak where, for many weeks, the priests had been making preparations for these great celebrations. Ceremonies performed in this resplendent setting included the presentation of offerings and prisoners-of-war to the god, Amen-Re, to honour him as the divine author of Egypt’s victories.

As a reward for his services as a professional soldier, Amenemhet had already received land from the king, where he had established a fine country estate. This property was free from any charges, and he planned to hand it on to his descendants. Amenemhet was a man of good character who was careful not to incur expenses he could not afford, but as a soldier, he enjoyed the additional reassurance that he could not be thrown into prison for debt. Indeed, military service had given him rapid wealth and promotion, and there was always the possibility, once his best fighting years were over, that the king would appoint him to a senior position at the Royal Court where he would enjoy many privileges. Kings sometimes made these promotions from the ranks of senior army officers (for example, the post of ‘Tutor of the Royal Children’ had been filled in this way). They hoped that this personal honour would ensure the men’s loyalty at Court, and offset the lack of support they sometimes faced from members of the nobility.