Tuneraru Customs

Nefert, Khary’s mother-in-law in our imaginary family, had not survived the year. She became increasingly debilitated with her chronic illnesses and afflictions, and suffered particularly from pain and breathlessness, the results of sand pneumoconiosis. Much weakened, she eventually succumbed to a bout of pneumonia, and passed away in her sixtieth year, during the fourth month of Shemu. By ancient Egyptian standards of life expectancy (the average age was about forty), Nefert had enjoyed a long life, but nevertheless, her death came unexpectedly, and the family were thrown into a state of deep mourning.

Urgent preparations had to be made for elaborate funerary and burial arrangements, which would ensure that Nefert had every chance of surviving death and attaining immortality.1 From the Middle Kingdom onwards, the Egyptians believed that every person, whether rich or poor, could aspire to an individual eternity which they hoped would be spent in the kingdom of Osiris, god of the dead.2

This realm was envisaged as a land of eternal springtime which mirrored Egypt itself, but was free from illness and suffering. The Egyptians believed that this place, known as the ‘Fields of Reeds’, was situated somewhere beyond the western horizon. Poverty was no bar to entering this kingdom; the requirements were personal piety, performance of the correct burial procedures, and a successful outcome before the tribunal of forty-two divine judges at the Day of Judgement.3

On this occasion, the deceased was required to attend an interrogation and recite the ‘Negative Confession’ – forty-two statements which denied any personal guilt of various sins, crimes and misdemeanours. Scenes on coffins and papyri which depict this event show the confession taking place in front of a balance: one pan holds the person’s heart, while the other contains the ‘Feather of Truth’. If the person lied, then his heart would weigh against him, but if he was innocent, then his heart and the feather would achieve an equal balance, and he would be declared ‘true of voice’.

Wooden statuette of the god Osiris, showing him as a mummiform figure holding the symbols of kingship – the crook and the flail. Traces ofpaint remain, as well as the copper inlays for the uraeus (snake) on the front of the headdress, eyebrows and outlines of the eyes. From Saqqara. Dynasty 26. Manchester Museum.

If the deceased successfully convinced the divine judges that he was innocent of all sin, then his body would be reunited with his soul, and he would pass into Osiris’ kingdom.4 However, if his heart weighed against him, then his body (or, in some instances, his heart) would be thrown to a fearsome creature known as the ‘Devourer’, whose body combined parts of several different animals. This creature would then consume the deceased’s body, thus destroying his chance of attaining eternity.

Funerary Customs

The Tomb

According to custom, Nefert’s husband had started to prepare a tomb for himself and his wife as soon as they married and established a home. Known as the ‘House of the Ka’, the tomb was regarded as a home for the spirit (Ka) of the deceased. The Ka could return to the tomb at any time, in order to gain sustenance from the food offerings placed in the adjoining chapel or from the menu inscribed on the tomb walls.5

Courtyard in front of an official s tomb. West Bank, Thebes. New› Kingdom.

View of the Valley of the Kings, Thebes, with the mountain behind. The pyramid shape of the mountain (known as ‘the Peak’), as well as the site’s isolated location, may have persuaded the kings to select this area for their tombs when pyramid-building was discontinued. New Kingdom.

Kings of the New Kingdom were no longer buried in pyramids, choosing instead to be interred in rock-cut tombs in the Valley of the Kings on the West Bank at Thebes.6 Here, one day, the body of Tuthmosis III, the king whom Khary served, would be laid to rest. Unlike non-royal tombs, the royal burial place did not represent the king’s house. The royal tomb provided the king with a gateway to his eternal kingdom. It represented a sacred space (the interior walls were decorated with appropriate scenes and inscriptions from various funerary texts) where he faced and triumphed over various dangers, and was ultimately transformed from a living into a dead ruler.

During the New Kingdom, officials and their families who lived at Thebes were buried in tombs scattered across the West Bank necropolises. Nefert’s tomb was typical of a non-royal burial place for a wealthy family of Dynasty 18. In front of the tomb was an open rectangular courtyard which gave access to a rock-cut, inverted T-shaped offering-chapel. In the centre of the back wall of this wide, shallow chamber an entrance led off into a long, narrow room where statues of Nefert and her husband were placed in a niche cut into the wall at the far end. A concealed shaft at the rear of this narrow room gave access to two subterranean chambers which held the burials and tomb goods. This shaft was sealed and covered over after each burial, but relatives and funerary priests could continue to visit the offeringchapel, where they prayed and presented funerary offerings.

Many family burial places were built and decorated well in advance of death, but if preparations were not already in place, some tombs – probably owned by embalmers (wealthy men who mummified the dead) as a commercial investment – were available for sale at short notice. Less affluent people could either choose to share a rock-tomb, or to be buried in rock-cut recesses or pits that had no upper chambers. The poorest men and women were buried in mass graves.

Ostracon (limestone sherd) decorated with a unique sketch of a funeral at a rock-cut tomb. At the top of the tomb-shaft, a priest (left) holds a burning censer and pours out a libation, while four women raise their arms to lament the deceased tomb-owner. A man descends the shaft to enter the burial area where, in the left chamber, two kneeling mourners await the arrival of the mummy, preceded by a priest wearing the jackal-headed mask of Anubis, god of cemeteries and mummification. Two mummies from earlier burials can be seen in the right-hand chamber. Steps lead down to another room where the owner’s funerary possessions were stored. From Qurneh, Thebes. Dynasty 18. Manchester Museum.

Nefert’s deceased husband had made good provision for their burial, and their tomb was kept in good order. It was approached through a small, flower-filled courtyard garden, regularly tended by a paid employee, which emphasized the tomb’s role as the home of the deceased. The upper and middle classes believed that they would spend eternity in the kingdom of Osiris, but they also expected to pass time in the tomb. Here, the walls were decorated with horizontal registers of scenes depicting many everyday activities. At the funeral service, special rites were performed to magically activate these scenes, as well as the relevant funerary models and tomb goods. In this way, the deceased owner hoped to be able to derive pleasure and benefits from these activities and situations even after death. For example, scenes and models of food production ensured that he would have an eternal food supply; he was portrayed as well-regarded and successful in his career so that he would continue to hold high office in the next world; and pastimes that he and his family enjoyed were represented in the tomb so that they could continue to experience them after death.

Tomb Goods

The dead were believed to have the same needs as the living, and therefore it was customary to place food, clothing, jewellery, cosmetics, tools, weapons and domestic equipment in the tombs.7 Manufacturing tomb equipment played a key role in the Egyptian economy, and many workshops were engaged in the production of a variety of goods for the dead as well as the living.

Reed and pottery coffins had been used from earliest times to protect the dead, but from c.3400 BCE, a rectangular wooden coffin was introduced for the upper classes; this was probably intended to represent a ‘house’ for the deceased. Democratization of religious beliefs and funerary customs, which started in the Middle Kingdom, encouraged everyone to provide themselves with tomb equipment, according to their means.

Increasingly, the middle classes furnished their tombs with a range of burial goods which included a ‘nest’ of at least two coffins. The outer coffin, usually made of wood, was rectangular in shape; the inner coffin was anthropoid (body-shaped) and represented the deceased as a wrapped mummy. In the New Kingdom, this arrangement was replaced by a nest of two or even three anthropoid coffins. Coffin-makers, often employed in workshops run by embalmers, were members of a separate and distinctive craft who combined the skills of carpenter and painter. In addition to coffins, these men made wooden models and figurines, and other items for the tomb.

The external surface of a typical anthropoid coffin was painted with representations that imitated real items found inside the mummy: a bead collar, girdle, bandaging and jewellery. During the New Kingdom, coffin decoration also included scenes of gods, the Day of Judgement and the deceased’s resurrection, as well as inscriptions from funerary ‘books’.8 These contained spells to help the deceased enter and survive in the kingdom of Osiris; however, by this period, the spells were also inscribed in a more complete form on a roll of papyrus (the so-called Book of the Dead) which was either placed inside the bandages of the mummy or elsewhere in the tomb.9

Coffins and papyri were generally mass-produced, but most were also inscribed with the names and titles of the purchaser, in order to identify ownership. The coffin fulfilled a dual purpose: it protected the body and also provided a locus to which the deceased’s spirit could return at will. Facial features were represented in a stylized manner on anthropoid coffins: no attempt was made to depict the features of an individual owner. The eyes were painted or carved, and often inlaid with obsidian and alabaster to make them look lifelike. A separately-made wooden false beard was pegged into the chin; this beard indicated that the deceased had become an ‘Osiris’ – someone who had successfully faced the Day of Judgement had thus become a manifestation of the god.

Two canopic jars from a set of four, with human-headed lids. The name of the owner, Nekht-Ankh, is inscribed on the front of each jar These containers were used to store the owner s mummified viscera. From the Tomb of Two Brothers, Rif eh. Dynasty 12. Manchester Musuem.

Many tombs also contained a set of canopic jars. These were used to store the viscera removed from the deceased’s body during mummification. The viscera were cut out from the chest and abdominal cavities, and then natron was used to dehydrate them. Finally, they were either returned as packages to the bodily cavities or placed in containers known today as canopic jars.

Each set included four jars; they were dedicated to a group of gods known as the ‘Four Sons of Horus’ who protected the viscera and prevented the owner from experiencing hunger. When the jars were first introduced in the Middle Kingdom, their stoppers were often carved to represent four human heads. However, by Dynasty 18, the stoppers portrayed the ‘Four Sons’: Imset (human-headed) who protected the stomach and large intestine; Hapy (ape-headed) who guarded the small intestine; Duamutef (jackal-headed) who cared for the lungs; and Qebehsennuef (hawk-headed) who was responsible for the liver and gall-bladder. The ‘Four Sons’ were themselves protected by the goddesses Isis, Nephthys, Neith and Selket.

A funerary priest performed a special ritual at the burial service: known as the ‘Ceremony of Opening the Mouth’, this ‘brought to life’ all the tomb-scenes, statues, models, and the owner’s mummy.10 It was believed that this ritual charged them with a magical force so that they could be used by the deceased owner. When performed on the mummy, the rites allowed the owner’s spirit to enter the body, and restored his original life-force and physical capabilities so that he could function again in the afterlife.

Statues and figurines placed in the tomb represented the owner and sometimes other members of his family. Most of these images were not lifesize, but the Egyptians believed that the ‘Ceremony of Opening the Mouth’ would restore their original size and functional abilities. Most of these figurines do not show the exact facial features of an individual person, but items were given the owner’s identity by adding his name at the time of purchase.

A tomb assemblage usually included models of servants as well as statues of the owner and his family. Carved in wood, with painted details sometimes added to produce a realistic and lifelike appearance, these models often duplicated or resembled the content of the wall-scenes. Both were designed to provide for the needs of the owner in the next world. Some models represent a group activity; the most common examples show figurines working in granaries, breweries, slaughterhouses, kitchens or weaving workshops to produce food or textiles for the deceased. There are also models of the owner’s whole estate, complete with its villa, fields and herds, while other examples represent a single agricultural activity, such as men and oxen ploughing the fields. A special group of servant models known as ushabtis were included so that they could undertake agricultural work in the next world on behalf of the deceased (see above, p143).

From the Middle Kingdom onwards, tombs often included a model boat, or set of boats, so that the deceased owner could travel on the river.11 Again, the ‘Ceremony of Opening the Mouth’ was expected to restore these miniature versions to the full size and capacity of the originals. The model boats were made of wood, and have oars, deck cabins, crew, and linen sails; carefully carved or painted details were added. Wealthy people often included a variety of craft in their tombs for different purposes. For example, there are vessels to transport the body of the deceased across the river for burial in the necropolis on the West Bank; to take part in fishing expeditions to augment the owner’s food supply; and, most importantly, to enable him to make the journey to Abydos, the supposed burial place of Osiris, so that he could increase his chances of resurrection and eternal life.

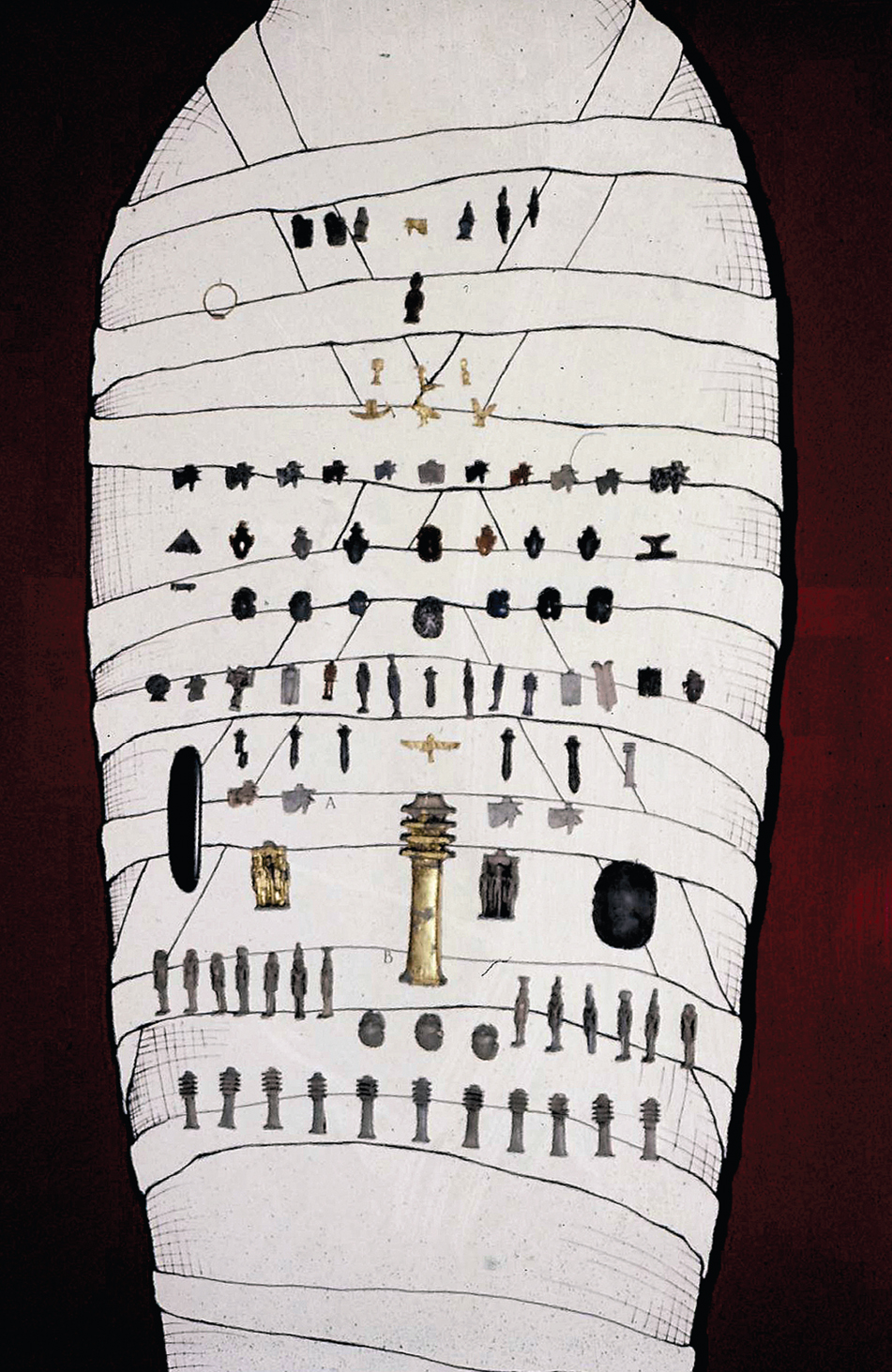

Amulets – sacred jewellery inserted between the mummy bandages – provided additional protection for the deceased (see above, p186). A particularly important amulet, the heart scarab, was placed amongst the bandages over the heart of the mummy. This essential item of funerary equipment often carried an inscription which invoked the heart not to speak against its owner when he faced the Day of Judgement.

Funerary amulets found on the mummy of a priest, Horudja. Archaeologists very rarely discover a complete set of amulets still in situ on a mummy. This display reconstructs the exact location of each amulet at the time of discovery: most noticeable are the large heart scarab (right, third row from bottom), the adjacent gilded Djed-pillar, and the slate finger (left) for covering the incision through which the viscera were removed from the body. From Hawara. Dynasty 26. Manchester Museum.

Nefert and her family had prepared for her burial in the traditional manner. Long before she was expected to die, they had purchased or commissioned essential tomb goods that would fulfil particular funerary requirements. Other items, such as food, clothing, cosmetics, jewellery and domestic utensils were added to satisfy Nefert’s everyday needs in the afterlife. Some of these were specially prepared for the burial assemblage, but Nefert had also instructed her daughters to include favourite possessions that she had enjoyed using and wearing when she was alive.

Mummification

It was now time to transport Nefert’s body from the family home to the embalmers’ workshop so that it could be prepared for burial. The workshop was known as the wbt (‘place of purification’), and was supervised by the embalmers. These highly skilled professionals were a special class of priests, and had some connections with medical practitioners. They conducted their work on a commercial basis, and supervised all the physical procedures and religious rituals associated with mummification. However, the man known as the ‘cutter’, who actually made the incision in the flank of the mummy to remove the viscera, was not himself an embalmer. The unpleasant nature and potential danger of this work (because it gave him direct contact with the corpse) meant that he was regarded as unclean and untouchable. He could never escape from this lowly status, and was always regarded as a social outcast – a member of a group that may also have included convicted criminals.

The Egyptians probably developed the process now known as ‘intentional mummification’ after a long period of experimentation.12 It was introduced for royalty and the nobility in c.2600 BCE, although the procedure may have originated at a much earlier date. The main aim of mummification was to preserve the body in as recognizable a state as possible so that the deceased’s spirit could return at any time, and use the body to partake of the spirit of the food-offerings placed at the tomb.

Mummy of a child aged about six years. The body is well preserved; the eyelashes are visible and traces of gilding remain on the face. Unprovenanced. Graeco-Roman Period. From the Stonyhurst College collection, now in Manchester Museum.

During the Middle Kingdom, the middle classes adopted mummification as part of the democratization of religious and funerary beliefs and practices that occurred at that period. It became universal for royalty13 and the upper and middle classes throughout the pharaonic period, and some people continued to mummify their dead even in the Christian era.

Poor people, however, were always simply interred in shallow graves on the edge of the desert, where the heat and dryness of the sand preserved their bodies (a process known today as ‘natural mummification’). Before c.3400 BCE, all Egyptians had been buried in this way, but a change in funerary architecture instigated the need to develop intentional methods of preserving the body. The new type of tomb (which Egyptologists call a mastaba-tomb) was used for the upper classes, and had a brick-lined burial chamber. This meant that the body decomposed rapidly because it was no longer directly surrounded by sand. However, funerary beliefs dictated that the body had to be preserved, and so it was essential to find another method of dehydrating the bodily tissues and preventing rapid decomposition.

There is no extant Egyptian account of how mummification was carried out, but presumably the embalmers handed down their oral traditions. However, detailed descriptions have survived in the works of two Greek historians, Herodotus (fifth century BCE) and Diodorus Siculus (first century BCE). These sources, and evidence provided by the mummies themselves, enable us to reconstruct the various stages involved in mummification.14 Herodotus describes three main methods which were available according to cost. The most expensive method – which members of Nefert’s social class would have chosen – involved two main stages: evisceration, and then dehydration of the body by means of natron. In addition, the body was anointed with oils, and sometimes it was coated with resin and treated with plants and plant extracts. According to the ancient literary sources, the procedure lasted seventy days, although modern experiments on dead rats have demonstrated that physical preparation of the body would not have exceeded forty days. The extra days would doubtless have been used for prayers and rituals.

Once the embalmers received Nefert’s body from the family, it was placed on a board or platform. The first step was to remove the brain, which was usually extracted via the left nostril and a passageway chiselled through the ethmoid bone into the cranial cavity. Using a metal hook, the embalmers then reduced the brain, and scooped it out with a spatula. Since the Egyptians regarded the heart and not the brain as the seat of the intellect and emotions, the brain tissue was considered to be unimportant, and so these fragments were discarded. However, the embalmers were not usually successful in removing the whole brain, and some tissue remained behind in the cranial cavity. Alternative methods of excerebration (brain removal) were sometimes employed; these involved extracting the brain either through the base of the skull or an eye socket.

Limestone statue of Anubis, the jackal-god associated with mummification and cemeteries. From Saqqara. Dynasty 26. Manchester Museum.

Next, the viscera were removed through an incision usually made in the left flank. The ‘cutter’ inserted his hand through this incision and, reaching into the abdominal cavity, he used a special knife to cut free the viscera which he then drew out of the corpse. Making a further incision in the diaphragm, he repeated the process and removed the organs from the chest cavity. According to custom, Nefert’s heart was left in place because of its importance as the supposed seat of her personality, and the kidneys also remained in situ (although Egyptologists have not identified any religious or philosophical explanation for this). The embalmers then washed out the body cavities with palm wine and spices, and inserted a temporary packing of dry natron, packets of natron and resin, and linen impregnated with resin; these helped to dehydrate the body and prevent the chest wall from collapsing.

The viscera were now dehydrated with a chemical agent. Salt or lime may have been used in some instances, but natron was the most popular choice. A mixture of sodium carbonate, bicarbonate, and some natural impurities, natron occurs in dry deposits in a couple of desert areas of Egypt. Used in its solid, dry state for mummification, it destroyed the body’s fat and grease and dehydrated the tissues – a process which successfully arrested bacterial growth and consequent decomposition. During the New Kingdom, the embalmers placed the dehydrated viscera inside the four canopic jars, but other traditions were followed in later times. In Dynasties 21 and 22, the organs were wrapped in four packages and replaced inside the chest and abdominal cavities, while later they were sometimes made into one large parcel and placed on the legs of the mummy.

Following evisceration, the embalmers packed dry natron around the body and inside the bodily cavities, and left it for a period of up to forty days. Then the corpse was removed from the natron and washed with water to remove any residual debris. As the body was still quite pliable, the embalmers were able to straighten it out so that it could be placed in a coffin.

The basic procedures had now been completed, but in order to remove any lingering odours and perhaps to try to deter any insect infestation, the body was anointed with cedar oil and sweet-smelling ointments, and rubbed with cinnamon, myrrh, and other spices. The flank incision was closed either by sewing the edges of the flesh together, or covering them with a metal or beeswax plate. Sometimes, molten resin was poured into the cranial cavity, or it was packed with resin-impregnated linen; the nostrils were also plugged with resin or wax, and finally, a resinous paste was applied to the whole body.

Two gold eye-covers (bottom). Unprovenanced. Roman Period. Three gold tongue plates. From Hawara. Roman Period. The eye-covers were placed over the eyes of the mummy, and the tongue plates inserted in the mouth to provide magical protection for the deceased. Manchester Museum.

The embalmers carefully wrapped Nefert’s mummy in linen clothes and bandages; they inserted amulets between the bandage layers, and extended her arms alongside her body. The mummification procedure now drew to a close, and the embalmer, acting in his capacity as a priest, performed a special ceremony which involved pouring a semiliquid resinous substance over Nefert’s mummy, coffin, and her viscera inside the canopic jars.

The Funeral

Once the mummification process was finished, Nefert’s family removed the mummy from the embalmer’s workshop and took it home. They now had to organize the burial ceremonies so that Nefert could finally be laid to rest. Since various stages of the funeral are depicted in wall-scenes in Theban tombs, it is possible to reconstruct the order of the main events.

Throughout the mummification process, Nefert’s family and friends had observed a period of mourning, abstaining from the pleasures of life: they did not bathe, wear fine clothes, or enjoy wine and good food. Now that the mummy had been returned to the house, all the women of the family, together with their relatives and friends, began to mourn outside the home. They rubbed dirt into their faces, tore their dresses to expose their breasts, beat themselves on the forehead, and wailed.

At last, the day of the funeral arrived. Nefert’s family and friends, together with professional female mourners engaged to perform the funerary chants, assembled at the family home to escort the body and the associated burial goods to the tomb in the necropolis on the West Bank. Leaving the house, situated on the East Bank of the Nile, the mourners boarded a special funerary barque to accompany the mummy on the short journey across the river. Nefert’s daughter, Perenbast, and other close female relatives, squatted on the deck, near the brightly painted, flower-strewn coffin which was supported on a bier. These women had tom their dresses and exposed their breasts as a sign of grief; now they bewailed Nefert’s death with the traditional eerie cries of mourning. Standing before the bier, the funerary priest burnt incense, recited special prayers, and made offerings on behalf of Nefert’s spirit. Another boat which sailed in front of the funerary barque accommodated other female mourners who also sat crying on the deck. A third boat conveyed Nefert’s male relatives, while a fourth was filled with servants who carried gifts and bouquets of flowers to leave at the tomb.

Once the boats had moored at the West Bank, the mourners disembarked to begin the final journey to Nefert’s tomb, which was cut into the cliffs behind the wide stretch of fertile land where crops were grown and harvested every year. As the procession formed, the funerary barque carrying the coffin was placed on a sledge drawn by two oxen; Nefert’s closest male and female relatives walked behind this, lamenting and beating their heads in grief. Distinguished by the panther skin that he wore around his body, the sem-priest (a special cleric who supervised the funeral) walked in front of the sledge. He poured a libation on the ground and wafted incense around the coffin. In front of him, another official sprinkled the ground with milk to ease the passage of the sledge, while a short way ahead, a herdsman walked alongside the oxen, urging them onwards with his whip.

Slowly, the procession wound its way across the cultivation and then ascended the steep pathway to the rock-cut tomb. Here, in front of the offering-chapel, the funerary officials placed the mummy upright against the entrance, where it was held and supported by a priest wearing a jackal-headed mask to represent Anubis, the god of embalming and the necropolis. Perenbast, the chief female mourner, knelt before the mummy, beating her head as a sign of grief; behind her stood a table piled high with food offerings. Four priests waited nearby to perform the funerary rites. One of these carried out the ‘Ceremony of Opening the Mouth’, touching the face of the mummy with an adze so that the life-force would be restored. Another poured out a libation of water to revivify Nefert, while behind him, the sem-priest offered up incense. A lector-priest stood behind this group, holding an unrolled papyrus from which he recited the funerary prayers. He led the main group of male mourners who, followed by the women, beat their foreheads and uttered shrill cries of lamentation.

The burial ceremony concluded with a meal for the mourners at the tomb; this repast closely resembled the banquets the family always enjoyed at home. According to Egyptian belief, the deceased’s Ka joined the mourners at this funerary feast, and they were all entertained by singers and dancers who had accompanied the funerary procession, and by a harpist who recited special songs which emphasized the joys of eternal existence. Most of these hymns were intended to revive the deceased and make provision for the person’s eternal welfare; they also gave the grief-stricken guests some comfort and insight into the meaning of the funerary offerings.

Although most songs emphasized the joys of eternal existence, some (which Egyptologists call Pessimistic Hymns) presented a less positive viewpoint. Remarkably, these hymns cast doubts on a major focus of the Egyptians’ lives by questioning the existence of an afterlife15 and whether there was any point in preparing and provisioning a tomb. They claimed that earthly existence was transient and there was no certainty about human life; funerary preparations did not last, and the dead did not return to tell the living what they needed in the next world. Instead, the hymns urged the listeners to enjoy life while they could, because the existence of an afterlife was so uncertain that even a well-provisioned tomb could not guarantee personal survival.

It is possible that these disturbing sentiments were first expressed in literature that dates to an earlier period of economic deprivation and political upheaval, when the Egyptians had reason to question their deepest beliefs and to speculate about the very existence of a hereafter. However, by the New Kingdom, the country was once again powerful and affluent, and these doubts and fears were less evident. During this period, most funerary texts attempted to reject any earlier scepticism, and to reassert a convincing belief in immortality. Nevertheless, tomb-owners evidently considered it advisable to present both viewpoints, probably so that the sceptical version could be aired and rejected. Therefore, some tombs were inscribed with a pessimistic hymn alongside one of the new compositions which gave reassurance about the joys and reality of eternal life.

Generally, songs of lamentation gave mourners the opportunity to confront their deepest fears, and reassured them that neither they nor the deceased tomb-owner would face the ultimate fear – the absolute or ‘second death’. The Egyptians dreaded this fate, reserved for the wicked or those who had not made correct burial preparations, because it resulted in complete personal oblivion or a form of semi-existence from which the deceased could not escape.

Reed coffin tied with ropes and a linen strip, containing the naturally mummified body of an infant just under three months of age. X-rays show growth arrest lines in the lower limbs, indicating a period of sustained illness. From Gurob. Dynasty 18. Manchester Museum.

Nefert’s body and its elaborate adornments were finally placed in the burial chamber. The fast-fading bouquets and garlands of flowers brought by the mourners remained on top of the protective nest of coffins which encased the mummy. Nefert’s relatives hoped that her burial would remain undisturbed; they prayed that she would attain eternity, and that one day they would be reunited with her in the kingdom of Osiris.

The family had made expensive and meticulous funerary preparations to try to ensure Nefert’s afterlife, but they were only too aware that the tomb would probably be plundered before many years had passed. As they and their guests began to leave the tomb and start the descent towards the river, they silently pondered the words of the blind harpist who had entertained them at the funerary banquet. No one admitted it, but the hymns offered little solace; doubts would always remain, and they could not ignore the final advice given in one lament:

‘Spend the daily happily,

Do not become weary of it,

Lo, no one can take his possessions with him!

Lo, no one who has departed returns again!’

(Harpist’s Song from the Tomb of King Intef. Author’s translation]