JUST THREE DECADES AGO, children in school learned by heart that Singapore’s population stood at around 2 million. Today, as it surges towards the 6 million mark, it seems that people, paradoxically, have grown lonelier. Such is the pattern of urban life everywhere: in the larger countries, people leave the comfort and support of their hometowns to find their fortunes in the big cities. But in Singapore, there is little distinction between “hometown” and “capital city” – it’s more or less a single unity that keeps changing at heart-stopping pace, exacerbating the disconnectedness between people and the places they grew up with, and among people as well.

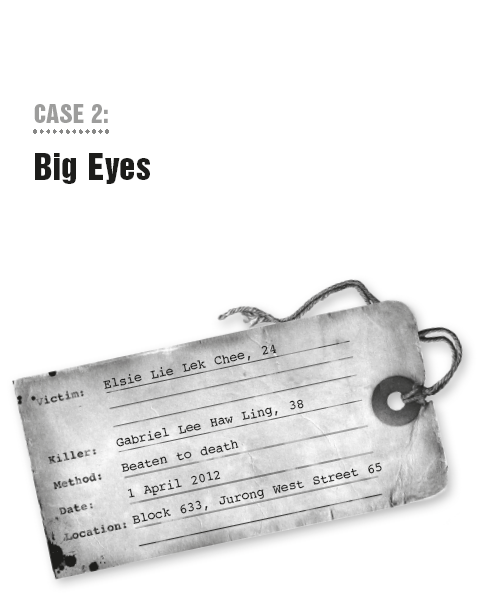

In this surging throng of humanity, Elsie Lie could be said to be unremarkable in every respect: a shy young lady who kept mostly to herself, she dropped out after a year at Jurong Junior College and started work as a site administrator at a subsidiary of Jurong Town Council. In the meantime, she planned, like many others, to brighten her prospects by enrolling in a communications course at a local polytechnic. Ordinary; but what happened to Elsie one Saturday morning was nothing ordinary at all.

Even as Elsie went about her life, she was also active in another pursuit: looking for friends and relationships online. She set up multiple personal profiles on numerous sites, making up for innate shyness by casting her social net wide enough to reach friends as far as India. She ended up finding traction much closer to home. By the latter half of 2010, she had found someone. She told her ex-boyfriend that she had an admirer, aged 27, and that she was unsure whether to date this person.

Early the following year, she called the ex-boyfriend again and this time, she was crying on the phone, saying that her new boyfriend had lied to her about everything: he was not 27, he was in fact in his late 30s; and married with two children! Besides lying about his age, Elsie’s boyfriend was also unemployed and made her pay for their dates and phone bills. These were a burden on Elsie as her job brought in but a little over $1,000. And then there was the communications course that she was considering – that would cost a fair bit as well.

But for all the wrong boxes ticked, somehow the relationship went on. On May 2011, Elsie updated her Facebook status to being “in a relationship” with Gabriel Lee, who was by then in the middle of divorce proceedings.

Then in January 2012, Elsie told her parents that she was moving out. Her parents tried to convince her not to, but to no avail. “She said she had started work and she wanted to learn how to be independent,” Elsie’s mother, a housewife, told the press. Renting a room on her own would take up a good half of her monthly take-home pay, and then there was her unemployed boyfriend she was supporting, so she also told her parents that she could no longer afford to give them a monthly allowance. “We just accepted whatever amount she gave. We didn’t ask her too much. We couldn’t force her to contribute when she didn’t have enough for herself,” said her father, a carpenter.

When Elsie and Gabriel moved in together to a flat in Jurong West, she left no forwarding address with her family, who also had no idea she had a boyfriend at that time. She rarely called home, though she did pay occasional visits.

“We welcomed her home. Even though she had moved out, we still cooked for her,” said her father; but it was as if she had excised her own family from the new life that she was living.

On her salary, she didn’t have enough to rent a whole flat by herself, so she rented a single room in a five-room flat, together with a Bangladeshi couple who were the main tenants, and another man, also a Bangladeshi.

Living together has its own stresses and though Elsie and Gabriel moved in together in January, the other tenants soon noticed around a month into their lease that Elsie herself rarely returned to the flat. One wonders about the type of relationship Elsie had with Gabriel; a clue perhaps is that on her Facebook page, one of her interests read “Stop domestic violence against women.” Even Gabriel was not sure where Elsie was spending her time during this period, because she did not return to her family home either, leading him to suspect that she was cheating on him.

The relationship did seem to turn for the better around late March, and the week before she was murdered, Elsie even returned to the flat. She did more than that: clutching a teddy bear and walking hand in hand with Gabriel, Elsie approached their ground-floor neighbours, the Ngs, on March 29 to announce that she was engaged and also to invite them to the wedding. “She was very childish, very cute,” recalled Mrs Ng. “They were a very loving couple.”

Prior to this exchange, Elsie had only spoken to Mrs Ng three times; Mr Ng thought it strange that she would invite them to her wedding when they barely knew her. On the other hand, Elsie’s own family, as it would turn out later, had no idea even about her engagement. Two days after announcing her engagement on 29 March, Elsie would be murdered.

Where a Friday night is usually a prelude of good things to come in this generally overworked country – restaurants are full, nightspots get noisier and the nation collectively relaxes a little to embrace the weekend – Elsie and Gabriel’s stormy relationship once again hit the rocks, hard. From 6.30pm, when other families would be having dinner in front of the TV, the couple were locked in a fierce quarrel for hours.

Indeed, it got so bad that at 1am, the police were called in by the other tenants to calm things down. The police left shortly after they came, as there seemed no grounds to pursue matters further, but half an hour later, the couple started quarrelling again.

Moans and groans were heard coming out of the room, but perhaps it was a sense of delicacy that held the other tenants back from interfering again. In any case, it started to rain very heavily around 2am, muffling the sounds further. It wasn’t until around 6am in the morning when the other Bangladeshi tenant returned from late shift work and found blood trails near Elsie’s room that the alarm was raised. He alerted the Bangladeshi couple, and they found Elsie in the room lying on her blood-soaked mattress.

The police were called and paramedics pronounced Elsie dead at 7.30am. But it took a while for the shocking events of the night before to be pieced together. Elsie had been slashed multiple times with a knife, and her eyes had been gouged out, likely with bare hands. The police found her eyes, pieces of her flesh, and a clump of her hair on the grass patch 14 floors below her flat: they had been torn off and flung out the window. The police also found signs that she had been tortured before she was killed.

Gabriel was arrested at the scene, and was charged the following day for Elsie’s murder. Elsie’s father was to tell the press later, “We blame ourselves for giving her so much freedom. We shouldn’t have done that. Maybe we didn’t show her enough concern. We didn’t restrict her enough.”

Elsie, just an ordinary girl, had been murdered by the person closest to her, under the very noses of the police and the people she lived with, on an island overcrowded with strangers.