CURRY IS ONE OF Singapore’s best-loved dishes, and being the most immediately recognised element of one of the four major racial groups that make up Singapore, it’s not too much to say curry is one of the pillars of Singapore cuisine. A hot, heady complex of spices in a thick gravy that makes anything it is slathered on instantly palatable, curry is a taste of Asia in one’s mouth: that particular facet of Asia that teems with colour, movement and unsubtle experiences.

Such is the potency of its taste that curry has been used every now and then by drug smugglers to mask the scent of their goods: as recently as September 2012, a smuggler in Birmingham, UK was jailed 12 years for trying to import 68kg of heroin, with an estimated value of more than $30 million, hidden in a container of more than 600 boxes of curry spice, seven of which were stuffed with heroin. Curry was also used to mask a murder – or a non-murder – in a case that set Singaporean tongues wagging in more ways than one.

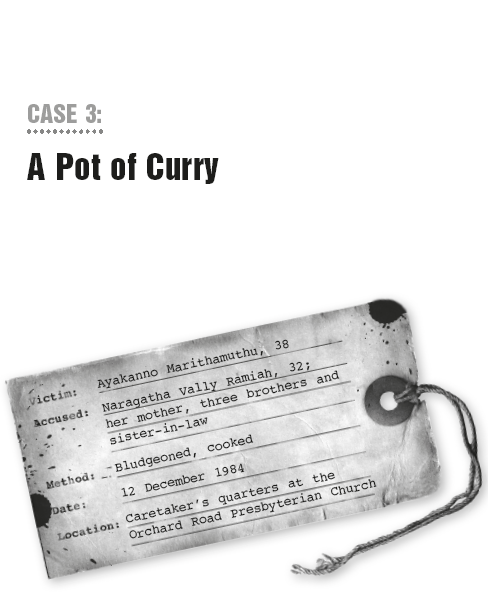

Ayakanno Marithamuthu, 38, worked for what was then the Public Utilities Board as a live-in caretaker at its Changi holiday chalets. People knew him as someone with a temper, though he would feel bad about it afterwards and sometimes even apologise the following day.

When drunk he would often beat his wife, Naragatha Vally Ramiah, 32. After suffering at his hands on one too many occasions, Naragatha finally decided that enough was enough, and hatched a solution together with her brothers that was brutal in its simplicity.

On 12 December 1984, after a day out with his brothers-in-law, Ayakanno was led to the caretaker’s quarters at the Orchard Road Presbyterian Church, where one of his brothers-in-law was working as a caretaker. There, Ayakanno was bludgeoned to death with an iron bar, and his body chopped into several pieces – presumably with skill, as one of his brothers-in-law worked as a butcher. Ayakanno’s body parts were then cooked in curry in a large aluminium pot like those one often sees at void deck wedding banquets, and apportioned into black plastic bags that were then disposed of at roadside bins.

Naragatha then reported her husband missing at Joo Chiat Police Station, saying he had told her he was going to the casino at Genting Highlands but had not returned. Somehow everything went on perfectly: nobody made any grisly finds, no stray dog chewed up a plastic bag of curry to reveal skull and bones; nothing happened, no alarm was raised and Ayakanno the wife-beater exited the land of the living without so much as a whimper.

Two years passed before a detective constable of the CID was tipped off in January 1987 that the reportedly missing Ayakanno had in fact been murdered in Singapore. Perhaps it was careless talk that betrayed a perfect crime. Investigations were soon mounted and two months later, at 2am in the morning on 23 March, the police swooped in and arrested eight suspects – three women and five men, all relatives.

On 27 March, Naragatha and her three brothers were charged with murdering Ayakanno at around 10pm on 12 December 1984. However, as then CID director Jagjit Singh told the press, “It was clear from the outset that this would be an extremely difficult case to solve as the alleged killing had taken place more than two years ago and the body had never been recovered.”

More than two years had passed: no remains were recovered, no murder weapon was found, and the account of Ayakanno’s murder only surfaced when one of those detained related the incident. Moreover, just a year before the arrests, the crime scene – the caretaker’s quarters at the church – had been renovated, including the kitchen and stove where the cooking allegedly took place. The pot in which Ayakanno was cooked was also never found.

As a result, the case was discharged in June that same year for lack of evidence, and Naragatha, her mother, brothers and sister-in-law were released, though it did not amount to an acquittal. As something of a parting shot, the deputy public prosecutor Ang Sin Teck declared that the police were still continuing with their investigation and that the prosecution had “every intention in future to charge the accused with murder.” Indeed, Naragatha’s three brothers were detained by the CID the very day of their release and detained till 1991.

But in the end, no one was convicted. Singapore’s sensational “Curry Murder” was a non-murder after all. But splitting hairs is a lesser crime than splitting skulls.