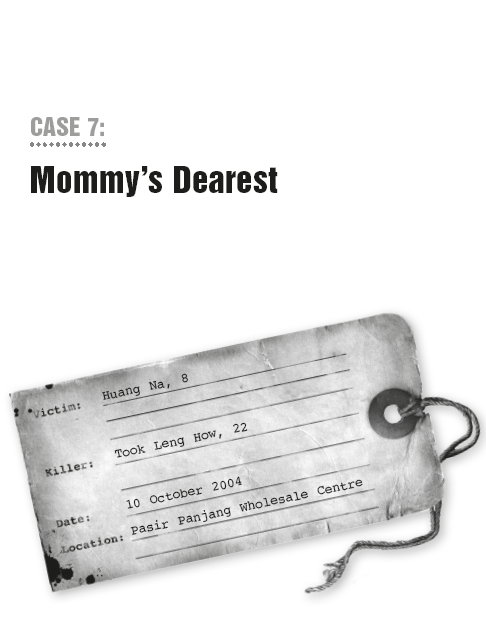

FROM FUJIAN PROVINCE in China, Huang Na came to Singapore in 2003 with her mother to enrol in Jin Tai Primary School on the West Coast (it no longer exists, having merged with Qifa Primary School in 2008). A bright student with many friends, Huang Na was dead in a mere one-and-a-half years, her body stuffed into a cardboard box dumped into the undergrowth at Telok Blangah Hill.

For its shock value, and the number of lives it touched in some way, Huang Na’s murder ranks among the major crimes to have gripped a relatively crime-free state. It wasn’t just that it involved a child, or the callousness with which she was killed by a trusted family friend; there was also something about Huang Na herself – her intelligence, independence, precociousness and not least her evocative face staring back from the tens of thousands of missing-person posters in Singapore, Johor Bahru and Kuala Lumpur.

In life, she was left much on her own; in death she had attention heaped back on her in spades. Her own mother’s neglect (it can only be that, objectively) gave way to the embrace of a very sympathetic public. Too late to do Huang Na any good; and even if her mother pocketed enough donations from Singaporeans to return to China a wealthy woman, it’s cold comfort for a child irretrievably lost.

Not many children can claim to have one parent who’s ever been in jail, but in Huang Na’s case, all three – father, mother, and stepfather – had criminal convictions and were formerly jailed and deported from Singapore.

Huang Na’s biological father, Huang Qingrong, got his first job in Singapore in 1996 by lying that he had a university degree. He was found out the following year and sent back to China. He then sneaked back a second time and worked illegally as a vegetable packer at the Pasir Panjang Wholesale Centre, and was jailed for this in 1999. That same year, Huang Na’s stepfather, Zheng Wenhai, was also jailed for two years and four months for robbery and overstaying.

Also jailed for overstaying and subsequently deported was Huang Na’s mother, but not before one of her fellow inmates taught her how to “beat the system”. Huang Shuying was back in Singapore in 2003 with Huang Na, a different name, and her fingertips intentionally scarred to bear her new identity, which allowed her to work as a vegetable packer at Pasir Panjang Wholesale Centre.

Did this same audaciousness, this willingness to live on the fringe of the law and beyond, translate into much hands-off parenting? In any case, Huang Na’s afterschool hours were spent pretty much on her own, as her mother worked long hours at the wholesale centre. In school, Huang Na was a bright student who learned fast and was good at math; though she was shy when she first came to Singapore, she made friends readily and quickly adjusted. It was her afterschool hours that differentiated Huang Na from most children her age, even considering the so-called “latchkey kids”: by most accounts, she thrived on the independence given her and grew up very quickly living among adults.

She once flew to China on her own to visit relatives, and beyond taking care of her own meals – she was often seen eating on her own at hawker centres in the area – she would also take care of others, cooking full meals for her flatmates and the foreign workers who lived next door to her. Moreover, she would also endear herself to the adults at her mother’s workplace. In a wholesale centre bustling with the buying, selling and delivery of seafood and vegetables, Huang Na was the only child who roamed around freely.

In her first six months in Singapore, Huang Na lived with her mother in a flat in Clementi shared with three of the latter’s colleagues: they would be her surrogate family, the people she spent much of her time with, sharing meals, laughing, playing. The one who seemed closest to her and spent the most time with her – Malaysian Took Leng How, already a father of two at age 22 – would turn out to be her killer.

It was Huang Na’s birthday on 28 September, but her mother had flown off to China the day before to visit relatives, so the child had to celebrate on her own. She took a bus to Clementi Central (by that time, Huang Na and her mother had moved to the employees’ quarters at Pasir Panjang Wholesale Centre) and bought herself a cake, which she shared with her neighbours. Her mother would not return to Singapore till two days after Huang Na was reported missing; she would never see her daughter alive again.

On 10 October, Huang Na had been on her own for almost two weeks, though her mother did ask two of her friends to watch over her child. Huang Na was seen around 1pm walking barefoot to a public phone booth, where she called her mother. The latter explained to her daughter that she was having flight problems, and would only be back two days later.

This was a Sunday: the normally busy wholesale centre was relatively deserted by now, since many shops had closed, and workers had left for the weekend. Elsewhere at the wholesale centre, a colleague was surprised to see Took still at the shop and offered him a lift back. Took declined, saying he was waiting for someone.

He was in fact lying in wait for Huang Na. The latter had just finished her phone call to her mother and was presumably walking home. Took approached her and asked if she wanted to play – he had her favourite mangoes, too, which they could eat together, as they had countless times before.

He leads her to Block 15, his employer’s storeroom, a little distance from the shop he works at. There, they finish the mangoes together before playing a game of hide-and-seek. Took has an idea: he will tie Huang Na’s ankles together with raffia string, and if she manages to untie herself before he finds her, she wins. The two have often played together; Huang Na likes playing with knots and is good at untying them. Many witnesses later testify that among the adults, Took was the closest to Huang Na and they spent much time playing and talking. They had also seen Took scold Huang Na before but that did not register as something unusual since children tend to be naughty at some time or other.

Took ties Huang Na up, turns off the lights and leaves the room to begin his countdown. Midway through, he hears a loud thud. He enters the storeroom and when he turns on the lights, he sees Huang Na lying face-up on the floor, with blood coming out of her mouth; her eyes are wide open and she is having a fit, her body in spasms. Took is alarmed at what he sees and panics. He turns Huang Na over, and aping what he has seen on TV, strikes Huang Na three times on the back of her neck with the edge of his hand. He then turns her over, and squeezes her neck till her face takes on a grey pallor. Then he turns her over again: he kicks and stomps on her repeatedly, to make sure she is dead.

Then he takes off Huang Na’s clothes, and sexually assaults her with his finger. He later tells the police he wanted to make it appear as if she was raped. Why? Over the course of the police questioning, Took would demonstrate a tendency to make bizarre claims about his actions and motives, while offering fantastical accounts of what happened.

Why should panic drive him to kill Huang Na with such violence? If someone were to have a fit, or be choking, the instinct would be to slap the sufferer’s back in the hope of dislodging any obstruction in the airway, and not to chop the back of the person’s neck. From the bruises that forensics teams later find around Huang Na’s upper lip and jaw, the prosecution at Took’s trial would lay it out that Took did not come into the room to find Huang Na in spasms on the floor. Instead, he must have sexually assaulted Huang Na while she was tied up, then suffocated the eight-year-old by placing his hand over her nose and mouth till she collapsed – a few minutes would have sufficed. With Huang Na motionless, he then delivered the blows to the back of her neck and stomped on her to make sure.

Took then stuffs Huang Na’s body in nine layers of plastic bags – each with their openings at opposing ends and tightly knotted – before sealing the body with tape in a cardboard box half Huang Na’s size. It is still daylight; he will have to dispose of the box at night to evade detection. He is careful to dispose of Huang Na’s clothes in a bin not monitored by CCTV; they are never found.

Meanwhile, Huang Na’s guardians are getting worried that she is nowhere to be found. She is known to be a responsible child; though she is sociable enough to talk to strangers, she knows enough to not go anywhere with them; and she always asks permission if she wants to stay out. But that Sunday afternoon, no one sees her about from around 1pm.

Took takes his time to wait for nightfall at his rental flat at Telok Blangah Heights. At 8.30pm, he has just finished watching a drama serial and asks to borrow his friend’s scooter. He goes to the wholesale centre and finds a flurry of activity at the shop. His colleagues and those who know Huang Na are by this time very alarmed that they have not seen the child since the afternoon, and are organising a search. A colleague later testifies to the police that amidst all that activity, he found it strange that Took appeared unperturbed that Huang Na was missing.

Took rides over to the storeroom at Block 15 to retrieve the box containing Huang Na’s body. He stashes this at the back of the bike and scoots off to Telok Blangah Hill Park, which is just minutes from his home. Then he hurls the box into the undergrowth and leaves.

Practically the whole nation is galvanised in the search for Huang Na. The police, taxi companies, and hundreds of volunteers are mobilised, and tens of thousands of missing-person posters are printed, which are distributed all over Singapore and even find their way to Johor Bahru and Kuala Lumpur. According to the police, the search for Huang Na was the largest manhunt in Singapore in the last five years.

When Huang Na’s mother returns from China two days after Huang Na goes missing, she throws herself headlong into the search for her daughter. Every day for several weeks, she wanders through public places and countless neighbourhoods, asking strangers whether they have seen her daughter, even trudging through Bukit Timah Hill and Mount Faber because a relative tells her she dreamed that Huang Na was kept in a mountain.

But Huang Na is nowhere to be found, not even with cash rewards donated by members of the public; phone-in tip-offs lead nowhere.

The police also begin to question people working at Pasir Panjang Wholesale Centre. Through these interviews, they establish that Huang Na was last seen on Sunday afternoon at around 1.40pm, walking off with Took. That makes Took the last person known to have had contact with Huang Na. The police then centre their enquiries on Took. But when they question him, Took casually denies any knowledge beyond having asked Huang Na not to wander about and to go home, and offers alibis – which later do not check out.

Still, there is insufficient evidence just yet for the police to classify Took as a suspect; and even in early statements to the press, Huang Na’s mother expresses disbelief that any harm to Huang Na could have come from Took.

With more than a week gone by without any leads on Huang Na’s whereabouts, on 19 October the CID are assigned to investigate. Their approach turns up a lead: they discover that Took’s employer also operates another premises away from the shop – the storeroom at Block 15.

On a cursory examination of the storeroom, one of the investigators has a hunch that Huang Na’s disappearance was as a result of a crime – though so far not enough information has surfaced to support this – and that the storeroom could be a likely crime scene. He calls for a forensics team to run through the storeroom with a fine comb. This detective’s hunch later proves to be correct, and yields evidence for the prosecution in Took’s trial the following year.

In the meantime, the police were interviewing Took intensively, though nothing material had surfaced. On 21 October, after a late interview session, the police asked Took to take a polygraph (lie-detector) test the following morning, to which the latter agreed.

As Took was being escorted by police officers back to CID – Took had asked to spend the night at the police station as he was worried he would oversleep and miss the polygraph test appointment – Took said he was hungry, so they stopped at a restaurant to have dinner. Midway through the meal, Took asked to be excused to go to the washroom. He didn’t come back.

This proved very embarrassing for the police, who had to explain to the public that Took was not at that point a suspect, though his passport had been impounded. A second blow was to come: at around 3am in the morning, CCTV footage reviewed later saw Took cross the Woodlands Checkpoint into Malaysia, right under the noses of the border officials of both countries.

The fiasco of Took’s escape had one upside, though: the police now had something more concrete to go on, as Took could not have fled for no reason. A couple of days later, the forensics team that examined the Block 15 storeroom came back with bloodstains that proved to be Huang Na’s, and denim fibres on the carpet – Huang Na was last seen wearing a denim jacket. Huang Na had been in the storeroom, and since only employees had access to the room, police could now have suspects in mind.

The police issued an warrant of arrest for Took on 26 October, for “abduction” – the police did not know then, or rather were not certain, that Huang Na was already dead.

After crossing the causeway, Took made his way to his hometown in Penang. He met with his family, and even gave newspaper interviews. For all the wild tales that he told the Singapore police, including how Huang Na was taken by Malaysian underworld figures and that he was himself a member of the underworld who wielded enough influence to secure Huang Na’s release, he spoke truthfully when he declared that he did not kidnap Huang Na. He just didn’t say that he had killed her.

Convinced that he was innocent (of kidnapping), Took’s father and family persuaded him to give himself up. Life on the run was no life; better to clear one’s name. This was advice that Took’s father would come to regret giving his son.

On 30 October, Took gave himself up to the Malaysian police in Penang. He was then whisked back to Singapore. Under interrogation, Took finally told the police that Huang Na was dead, and drew a map for the police that described where he had dumped her body. At around 10.30am the next morning, almost three weeks since Huang Na was reported missing, Gurkha officers trawling through Telok Blangah Hill found the cardboard box with little difficulty, in part from the foul smell emitted by its contents. The search for Huang Na had come to an end.

The media storm did not die down with the discovery of Huang Na’s body. Not when so much effort and emotion had been invested in finding her, not just by the people who were close to her, but by the public as well. There was an outpouring of sympathy, and generosity, as it turned out.

Took refused to testify on his own behalf. In court, his defence relied solely on the testimony of a single psychiatrist, who believed Took was schizophrenic. This he gleaned from Took’s account of seeing shadows, going to mediums, and his apparent lack of emotion as he related such acts as strangling and stomping on a defenceless child. Indeed Took would often smile during his trial. There was also his fantastical account of how three Chinese men had stormed into the storeroom as he and Huang Na were playing, who then killed and sexually assaulted the child and then left. Took’s “unshakeable” belief in the imaginary trio (there was no evidence to even suggest such thing) led the psychiatrist to think that he was simply not of sound mind and hence should be convicted with diminished responsibility, punishable by a brief jail term, not hanging.

However, the psychiatrist for the prosecution painted a different picture and this was the version the judge found more convincing. Took had been methodical and rational at every stage of disposing of Huang Na’s body – the careful wrapping and sealing of her body, and disposal by night to evade detection. Why would he make up something as the three men, and then confess that he had killed her out of panic? Why had he needed to take such pains to dispose of her body if Huang Na, as he claimed at one point, had simply choked on her own vomit and suffocated to death? Why had he needed to molest her with his finger as she laid dead at his feet, to give the impression that she had been raped? He was also found to have lied on numerous points – from fake alibis on the day of Huang Na’s disappearance, to how he paid an illegal immigrant to smuggle him across the causeway by sea, as often happens in Asian gangster movies. When shown video footage of himself walking across the border, he shrugged it off, claiming he cooked up the boat story so as to save border officials the embarrassment of having let someone through without papers.

In the end, Took was found guilty of murder and sentenced to hang. He appealed against the conviction, and the three-judge panel was actually divided in opinion, with one judge expressing that it was not beyond doubt that Took had murdered Huang Na. However, he was outnumbered by the other two judges, and the death sentence was upheld. A subsequent petition to the president for clemency, carrying some 35,000 signatures, also failed, and Took was hanged on 3 November 2006.

Through the whole episode, though there was an outpouring of sympathy for Huang Na, it was not long before some anger and resentment was turned towards her mother. What kind of mother would leave her daughter for weeks on her own in a foreign land without family?

While Huang Na had lived in relative neglect, the tussle over her ashes between her mother and stepfather on the one hand, and her biological father on the other, made news. Then there was the huge amount of donations that came in at Huang Na’s funeral. At first, Huang Na’s parents pledged to donate the excess from the funeral expenses to charity, but later on, her stepfather was quoted as saying that that would not be the case as their house in China needed renovation and that he had health problems that would require substantial expenditure on medical bills.

When a news reporter visited Huang Na’s mother five years on from the case, she found her living in a luxurious four-storey mansion the size of four basketball courts; and her stepfather, looking “plump and radiant”, was driving a car fitted with three TV sets. If it’s any comfort, at least now Huang Na’s parents are not letting her out of their sight: her grave can be seen from the fourth storey of the new family home.