Making a Plan

When you are at a crossroads in life, it can feel impossible to know which road to take. The possibility of making the wrong choice causes a lot of anxiety, fear—and even despair. In ancient times, the wrong choice meant getting lost and starving to death, or running into a passel of lions or an angry mob from a warring tribe. Today, when we come to a modern kind of crossroads, we often feel the same dread and paralysis. That’s because the part of our brain that deals with fear (the amygdala) is exactly the same as it was in humans living a thousand years ago. It’s known as the reptile part of the brain because it hasn’t evolved past the very basic functions that keep humans alive. In mythology, deals are made with the devil at crossroads, when most people are willing to lay down everything they have in exchange for just a little bit of certainty.

Before you go out and call up a crossroads demon, do yourself a favor and take a deep breath (and then keep reading). There is a logical way to go about making the best plan for what you should do after high school. It involves weighing your options and thoughtfully comparing the benefits and the costs of taking one path over another before you actually do anything.

VISUALIZATION

Okay, so you’re at a crossroads. In the previous chapters, you’ve already done what any explorer would do in a similar situation: You’ve taken stock of your constitution and the tools available to you. You now have at least some inkling as to what is going to fuel you on the next leg of your journey. You’ve considered your basic temperament and personal preferences, what kind of operating mode you tend to use most frequently, and which kind of activities and social scenes are the best fit for you. You’ve also thought about where you would go and what you would do if you had no obstacles in your way. So we know where you’re headed, and now we’re going to start filling in the possible routes to that destination. But there’s one more step I want you to experiment with before we get into specific options and possibilities. It’s a technique called visualization.

Visualization is related to your dream plan. It’s a mental rehearsal in which you imagine having or doing what you want and thinking through the various permutations of routes that will take you there. It’s a tactic that’s used by athletes, entrepreneurs, and executives to envision their goals so that they can achieve them more efficiently. Using our exploring metaphor, it’s like creating images in your mind of the landscape you think lies ahead of you and mentally rehearsing how you might navigate it. It can also be defined as a thought experiment.

So, go back to your dream plan for a second and create an image in your head of what it would be like if it really happened and how you might get there. Don’t worry if it sounds stupid or unattainable in real life. That’s the point. If you actually knew, you wouldn’t consider yourself undecided. Just close your eyes and see yourself getting to where you want to be . . .

All done? Good.

Because, now it’s time for a little dose of reality. I know you have what it takes to do whatever you set your mind to, but for most people that’s not as easy as it sounds, no matter how amazing they may be. If your destination is completely out of whack with the tools and fuel you have to work with at your starting point, you are going to have to adjust your expectations of what you are able to do; or map out an entirely different route; or prepare yourself for some very, very hard work. Let’s be honest. No matter how much someone might get attached to the idea of summiting Mt. Everest, it’s not going to happen unless they have the constitution, the right supplies, a plan, and some help along the way. Otherwise, things are going to end badly. On Mt. Everest, “badly” means freezing to death; here, closer to sea level, it’s usually a bit less dramatic—but still something you want to avoid. I know it’s a downer, but here’s what it’s going to take to get real.

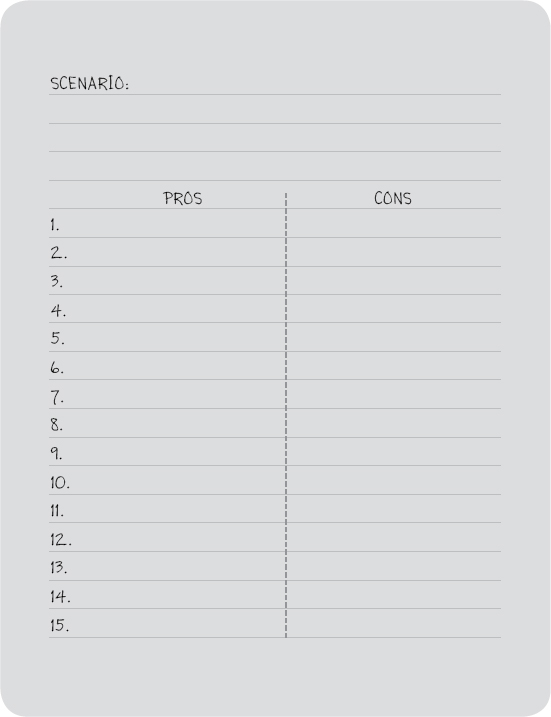

PROS/CONS WORKSHEET

As you read through the different possibilities sketched out in this book, you can use this worksheet to sketch out the real-life pros and cons of the various scenarios that appeal to you. In each section, I will try to outline the general costs and benefits of an option that should be weighed as part of your decision, but I can’t know your personal details. There may be specific reasons why one scenario works better for you than another, so it’s best if you keep your own lists. This will serve two purposes: It will help you to analyze what is really important to you, and it will keep you more flexible when it comes to making your final decision. In other words, it will help you figure out what is nonnegotiable for you and what you’re willing to give-up.

In fact, it doesn’t hurt to try this pros/cons worksheet out right now— if you have even the slightest leaning toward a certain direction, it might be worthwhile to look at the facts on paper. Take stock of your current outlook. All you need to do is use this worksheet or take out a blank piece of paper and create your own worksheet, modeled after this one. At the top, write out the plan of action that you’re leaning toward or most concerned about (aka your “scenario”), and then make two columns: At the top of one, write “pros;” at the top of the other, write “cons.” Then, as quickly as you can, list out those benefits and drawbacks. Whether you’re wondering which school to go to or whether you want to go to school at all, there’s no better way to examine your own feelings about the various options that lie before you.

So let’s say you are thinking about college. Pros could be that you’ll get a higher education, get out of the house, meet new friends, and earn some respect from your peers. Cons could be that you have to split-up with your girlfriend or boyfriend, take out a loan, or work with a teacher after school to help you raise your grades.

Remember to fill out a pros/cons worksheet for every possible scenario to refer back to. It will be really helpful in the reality-check department. You should be able to see right away if the pros outweigh the cons, or vice versa, just by how long the list is on each side. This is your starting point.

At this stage of the game, the most promising course of action is probably going to require some outside help. If that’s true for you, it’s important to take a moment to note the people you’d need to bring on board as advisors, mentors, or aides. The most obvious ones already surround you: your parents, teachers, and coaches, and the parents of friends. In some cases, however, you may want professional help from people who have intimate knowledge of the industry or field you’re curious about—independent college counselors, for instance, or military recruiters, or even local business leaders. I’ll list good databases to search; for other situations, I’ll recommend asking your school guidance counselor.

Once you have read through the rest of this book and used your pros/ cons worksheet that takes into consideration your new, expanded sense of self-knowledge, you should be able to settle on one course of action over the other. This will be your preferred road map, or Plan A. Use it to present your thinking to your parents and teachers, and anyone else invested in your future, to get their buy-in. You should keep a Plan B in your pocket, and maybe even a Plan C, just in case Plan A is a non-starter. If you don’t get buy-in, it’s another reality check (and one to list as a major con). There are very few people in the world, if any, who can make lightning in a bottle all by themselves.

EXECUTING YOUR PLAN

A plan without action is like a car without wheels. It fails to do the very thing it was designed to do, and—even worse—it’s a waste. In the case of a car, it’s a waste of space; in the case of a plan, it’s a waste of time. Now that you have a rough idea of what you want to do, start to think practically about how to make this plan a reality.

Because planning for big life events and goals is complex and time-consuming, it can be helpful to take a step back and consider what the execution of a plan means. Whether you’re just getting started or want to do a kind of status check, the following steps represent a fair picture of what a plan in action requires from you, in real terms.

These are the steps—but how they are taken is entirely up to you.

Portrait of a Plan in Action

- You commit to the plan, after weighing pros and cons.

- You obtain all the necessary information (whether via download, a library, a bookstore, or an agency or organization, as the case may be).

- You talk to your parents and any other adults who may have insights or advice to offer (or who simply need to approve the given plan).

- You create a time line and a checklist for action points.

- You review your budget in light of expected costs.

- You take action—delivering all necessary paperwork and deposits on time.

- You make travel plans and/or living arrangements.

- You wrap up loose ends.

Let’s say, for instance, that a common thread in your activities list is building things and using your hands. Maybe you think that learning carpentry skills could be a good way to support yourself. You might also like the idea of being able to build your own house someday, maybe even designing it, maybe even becoming an architect—but for right now, given what you have to work with (your starting point), carpentry seems like a good scenario. What next?

Take out your pros/cons worksheet and put “Carpentry” at the top. Then, list the first pros and cons that come to mind. If, after looking at the initial pros and cons (there may be more to add as you move along in the process), the scenario still seems pretty good, commit to the idea. Here’s where your car moves into first gear. Start researching journeymen certification programs in carpentry by going online and/or asking your school guidance counselor. There may be a good trade school near you that fits the bill (see Chapter 8 for more specifics), or an online course that will help you get started. Once you have specific information, print it out and talk over the options with your parents. The information should be as detailed as you can make it. You’ll want to know exactly what you might be signing up for, such as buying necessary tools/supplies, program fees, workshop space, how many hours it takes to get certification (a must if you want to subcontract for other people), and what kind of apprenticeship opportunities, skills, and/or portfolio you will have at the end of the program.

If your parents/advisors accept your plan, discuss your needs and specific schedule. Then you will have to grapple with how to pay for it. We’ll talk at length about budget in the next chapter, which will help you estimate how doable your plan is financially. Once you have an idea of how much you can afford, it’s time to fill out the application and make your deposit. In the time remaining before the program starts, you’ll need to assemble the necessary gear, get the appropriate materials and space to work with, and clear your schedule of other obligations so you can focus on building your new skill. If your budget is dependent on you getting a part-time job to pay for your program, you should take this time to get that going.

Changing your mind is your prerogative and should only be an issue if you have enlisted in the military or have laid down some fat stacks in a deposit that you can’t get back (be careful of this, especially with online courses). If you aren’t sure about a given program, you might be able to try it out first by taking a summer course or night class. If you can’t transfer or drop the plan without big penalties (or, in the case of the military, possible prosecution), you need to dig deep and persevere. There was a reason you thought this plan might be good, so go back to that. Hold that in your mind and work hard to get what you can out of the program. And recognize that sometimes we don’t know what skills will come in useful later on.

But if something is really not right, and you know it in your bones, no amount of money, time, or perseverance is going to make it right. In this case, you will have to figure out a way to exit gracefully. Often, this will require you presenting an alternative plan—and it should be really tight. You will have eaten up some of your credibility with your folks, but you should be able to earn it back if you have clear reasons why plan A is not working out, and why plan B has the potential to last. And it goes without saying—but I’ll say it anyway—that you should not stick to a plan if you are being mentally, physically, or financially abused or discriminated against by the people in control.

KEEPING IT REAL

Any plan you make—tentative or actual— should address the following basic questions:

| What? | College, service, work, travel, independent study, time off, hybrid |

| Where? | Local, national, international, hybrid |

| Who? | Kind of institution, program, business, or organization, or self-guided |

| When? | Time span |

| Why? | Education, self-improvement, self-knowledge, skill training, stress relief, strength building, self-invention, development, cross-cultural literacy, language development, personal growth |

| How? | Potential wage, stipend, loan, or other financial support; travel, transportation, living situation, health care. |

I want to say something about talking to your parents, because the more traditional or restrictive your family culture is, the harder it will be to do something unexpected. Only you know what the culture of your family is and how well your plan is going to be received. It may feel easier right now to go along just to get along (that is, to enter a pre-med program because your parents are both doctors, or to forget your dream of becoming a dancer because your parents find it unrealistic), but if every instinct is telling you to do something different, pay attention to it.

Many people reach middle age only to freak out because they finally come to terms with the fact that they’ve been living somebody else’s idea of a life—usually with a script written by their parents’ expectations. That’s why you’ll find so many forty- and fifty-somethings getting divorced, learning how to skydive, quitting their jobs, and generally doing what they should have done back when they were your age. I’d like to short-circuit the freak-out for you and have you do what you really want to do now, when you have fewer responsibilities, more time, and more energy. If it feels hard to talk to your parents now, think about how it might feel someday to talk to your spouse and/or kids, or your employer, and announce that you are leaving your life behind to go and find yourself.

If you’ve sketched out a plan and begun to narrow in on specifics, you have already made it a lot harder for your parents—or anyone else— to doubt you. They may have legitimate concerns at this point—and if they do, you should absolutely give them a chance to air those grievances. In which case, pay attention! Your parents have known you over your entire life, and they may have some insights or ideas that you didn’t think of yourself. Moreover, it will be much easier for you emotionally, and far easier financially, if they can assist you a little—by funding your plan outright or by helping you get aid or other kinds of financing, like a bank loan.

If your parents are still dead set against your plan, for whatever reasons, enlist the help of another relative, or a teacher or counselor, to mediate your conversations. Go over the pros and cons step-by-step so your parents can understand your thinking. Try to be understanding of their point of view and life experience. If you don’t mind compromising, see where along the way you could do this without sacrificing your dream.

If all else fails, and if the walls of resistance fail to crumble before your dream, work around those barriers. Respectfully agree to disagree, and go after alternative forms of support. Appeal to your guidance counselor at school. Find scholarship opportunities (see page 71 to get started). Reach out to a teacher or another adult you can trust and ask for advice. At age eighteen, you will be legally considered an adult and can make your own way. In the end, if you are happy and can support yourself, your parents will come around.