Introduction Victoria’s Secrets

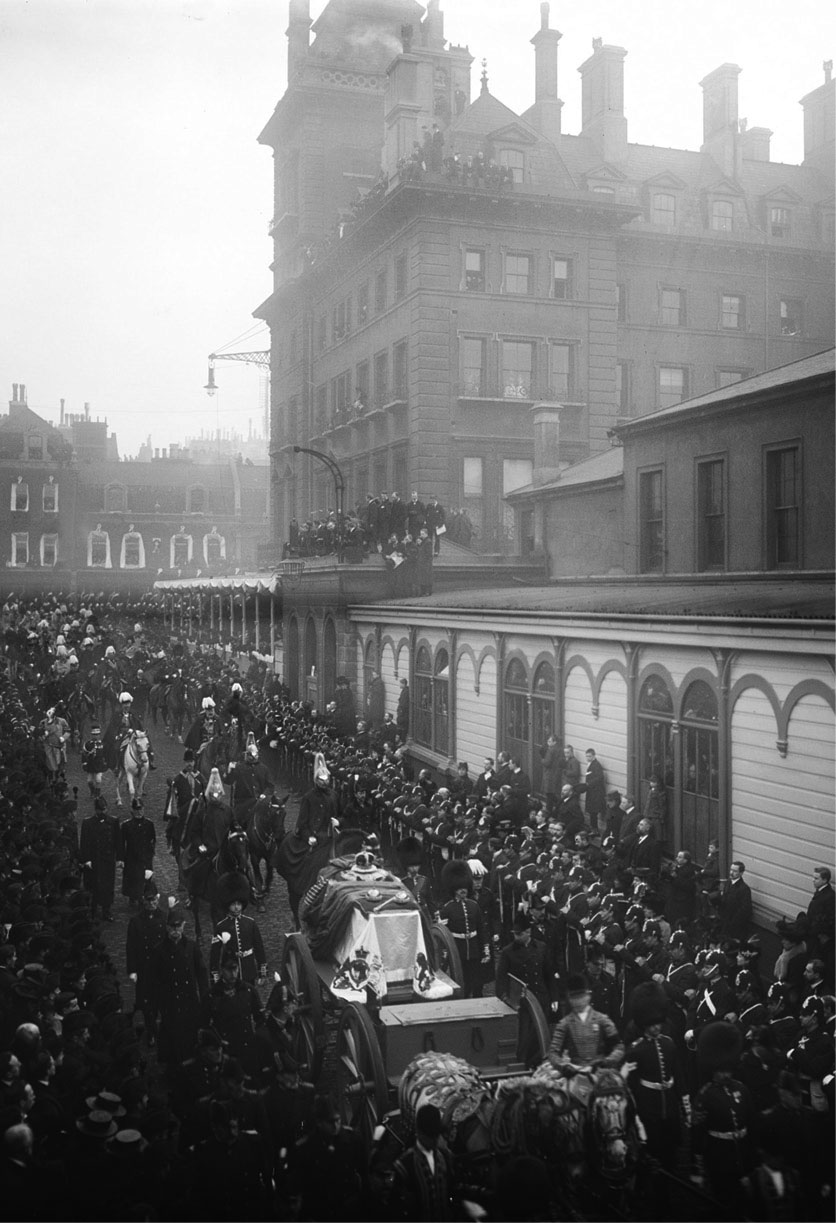

The funeral of Queen Victoria on Saturday 2 February 1901 was a very public affair, but it spoke volumes about her private life. On a bitterly cold day, with snow swirling in the air, more than a million people turned out on the streets of London and Windsor to pay their respects. Despite the numbers, people were eerily silent as the coffin passed by, the only sound being the muffled drums and the gun salutes fired at regular intervals in Hyde Park. The writer John Galsworthy recorded, ‘People gasped at the sight of the Queen’s white-palled coffin as it passed – a mourning groan… unconscious, primitive, deep and wild.’

The words of another observer, Lady St Helier, were even more poignant. ‘I was fairly taken by surprise which seized me by the throat, when the low gun carriage hove into sight,’ she said. ‘The tiny coffin draped in softest white satin – the whole thing so pure, so tender, so womanly, so suggestive of her who lay sleeping within – that every heart, one felt, must needs go out to meet her.’ ‘We all feel a bit motherless today,’ wrote novelist Henry James. It was as though London was in mourning not just for its queen but for itself and the end of an era.

In her flower-bedecked coffin, she was hidden from view, much as she had been for most of her life since the death of her beloved husband Prince Albert 39 years earlier. The women mourners wore black, as Victoria herself had done throughout her long widowhood.

Inside the coffin, she wore a white dress and her lace wedding veil. Beside her lay Prince Albert’s dressing gown along with a shawl made by their long-dead second daughter, Princess Alice, a plaster cast of Prince Albert’s hand, mementoes of virtually every member of her extended family, her servants and friends, including an array of shawls and handkerchiefs, framed photographs, lockets and bracelets, and a sprig of heather from Balmoral. On her hands were five rings given to her by Albert, her mother, her half-sister Feodora and her daughters Louise and Beatrice, and the gold wedding ring that once belonged to the mother of her gillie, John Brown, which she had worn since his death.

Framed photographs of Albert, her children and grandchildren were put in the coffin for good measure, along with a colour photograph of John Brown in a leather case plus some locks of his hair. Other photographs of Brown, which she used to carry with her, were to hand and even his handkerchief was laid upon her.

After the funeral service at St George’s Chapel in Windsor, the coffin remained in the Albert Memorial Chapel until 4 February when she was laid to rest beside her beloved husband in the Romanesque mausoleum at Frogmore, adjoining Windsor Castle. In attendance were many members of her extended family.

Queen Victoria died at Osborne House on the Isle of Wight on 22 January 1901 and her body was brought to London for procession through the streets before being carried by train to Windsor.

Well connected

As royalty, these people were public figures, but behind closed doors they all played a part in the private life of the woman who came to be called the ‘Grandmother of Europe’. Among the party were her sons Bertie, recently crowned King Edward VII, and Prince Albert, Duke of Connaught, along with her grandsons Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany in the uniform of a British field marshal, his brother Prince Henry of Prussia and the Prince of Wales, later George V, with his son, then Prince Edward of York and later, briefly, Edward VIII. Also in attendance were Victoria’s daughters, Princess Beatrice of Battenberg, Princess Helena of Schleswig-Holstein, Princess Louise, Duchess of Argyll, and Princess Victoria, formerly German Empress and Queen of Prussia, along with her granddaughter Princess Maud of Denmark. Victoria’s elder cousin King Leopold II of the Belgians, Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria and Tsarevich Michael, the brother-in-law of Victoria’s pretty granddaughter Alix, were also there, along with a handful of other crowned heads of Europe who were related to Victoria in one way or another.

After the Queen had been laid to rest, the statues and private memorials that Victoria had created for Brown were destroyed on the orders of Edward VII. Brown, who had been her closest confidant after the death of Prince Albert, had been replaced in Victoria’s affections by her Indian servant Abdul Karim when Brown died in 1883. After her death, his home at Frogmore Cottage was raided and their correspondence burnt. Karim and his family were promptly evicted and sent back to India, which had long been the jewel in Victoria’s crown.

Victoria is the second-longest-reigning monarch after Elizabeth II and she ruled at the height of Britain’s power on the world stage. Although numerous wars had been fought in the name of the ever-expanding British Empire, Victoria herself was seen as a symbol of stability and domesticity both at home and abroad. When she was born, 91 years earlier, the country had just been victorious in the Napoleonic Wars and Bonaparte was safely locked up on the island of St Helena. With her as the national figurehead, Britain had developed the only truly industrialized economy and was the world’s foremost naval power. In the 99-year Pax Britannica when Britain took on the role of global policeman, which lasted until the First World War, the empire grew without cease until it ringed the whole world.

Against this background of ritualized pomp and power, Victoria was a passionate woman who led an often turbulent private life. And once she was dead, Edward VII, whose youthful indiscretions Victoria blamed for the death of Prince Albert, reverted to the dissolute ways of Victoria’s Georgian forebears. At his coronation, his numerous mistresses occupied a gallery above the chancel in Westminster Abbey known as ‘the King’s loose-box’.

Meanwhile, two old Etonians, Arthur Benson and Lord Esher, set about editing Queen Victoria’s letters, deleting anything that might have been considered, in those days, compromising or distasteful on the one hand, or even mildly affectionate on the other. Victoria’s youngest daughter Princess Beatrice was charged with doing the same thing with her mother’s diaries and other papers, copying out sections she deemed suitable for historical record, while destroying the originals. This task was still going on in May 1943, when she wrote to Victoria’s great-grandson George VI, saying: ‘You may not know that I was left my Mother’s library executor, & as such, I feel I must appeal to [you to] grant me the permission to destroy any painful letters. I am her last surviving child & feel I have a sacred duty to protect her memory. How these letters can ever have been… kept in the Archives, I fail to understand.’

Victoria had remained on the throne through times of revolution, surviving rapid social change and eight assassination attempts, while Beatrice had lived through the Great War and seen many of the royal houses of Europe fall. For her, it was vital to keep the image of the Queen-Empress pristine. For all time, Victoria must remain the virtuous and selfless monarch. Fortunately, some copies of her most intimate private papers survived.