THE YOUNG PAINTER STOOD IN HIS STUDIO AT SOME DISTANCE FROM the large panel, fixing it with his gaze: David staring at Goliath just before he raised his sling to slay the giant with a single, perfectly aimed shot.

Standing on the table are two bottles containing oil and varnish. Beside them lies the grinding slab, still bearing splashes of blue paint. On a nail hammered into the wall hang two clean palettes, the smaller over the larger one, like a fried egg.

The painter stands motionless. Rembrandt probably took himself as the model, but he is not very recognizable. He has parsed himself into a sketch. A stripe for the mouth, two black dots for the eyes. His clothing is layered. The blue-grey tabard, its sash tied elegantly around his waist, reaches down to his shoes. It cannot have been warm in the studio.

His right hand dangles, the brush held between thumb and index finger. His left hand is held against his chest: the rest of the brushes stick up, the palette is to the side, where we cannot see it. With his little finger he clasps the long maulstick, on which he rests the ball of his thumb as he confidently places his brush on the panel.

The studio is bare; there is just the painter with his panel. No visitors are to be admitted; the door is securely locked. There is no key. There are no objects that might interrupt the gaze—a gleaming shield, a musical instrument, a book or a snuffed candle—and suggest a symbolic interpretation. As a result, our gaze continues to hover in the space itself, in that golden light, past the shadow of the easel on the wide floorboards and the cracks in the stucco of the walls.

The painter works in a seated position: that much is clear from the worn places on the horizontal beam of the easel. So he must have moved the chair out of the way; it was blocking his view. What did he see?

The most fascinating thing about this little painting is that we have no idea. The artist has turned the dark back of the panel towards us, leaving us to visualize whatever image we please.

There is one possibility that solves the mystery while preserving it. It is that the painter is rapt in thought, still deciding what he is going to paint. Could the panel be blank and bare, like the studio itself? That would mean that Rembrandt has here depicted the process of conception or inventio. In his mind’s eye, the painter sees the image gradually form.

He thinks: That is how I will do it.

His life began in Leiden. Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn was born in 1606 into a large family, as the youngest son of the miller Harmen Gerritsz and the baker’s daughter Cornelia Willemsdr van Zuytbroeck, known as “Neeltje”. He grew up in Weddesteeg, behind the western embankment on which stood his father’s mill. The family took its name from the Rhine, the river that flowed out of the city at the end of the alley, towards the polders of Holland and onward to the endless sea.

The Painter in his Studio, c.1628.

“R” or “RH”: that was how Rembrandt signed his work when he first set up as an independent artist in Leiden. Some three years later he switched to the letters “RHL”, and in 1631, the year of his move to Amsterdam, he would occasionally sign “RHL van Rijn”. The three elegantly penned initials stand for “Rembrandt Harmenszoon Leidensis” and represented a tribute to his origins: to his father and the city of his birth.

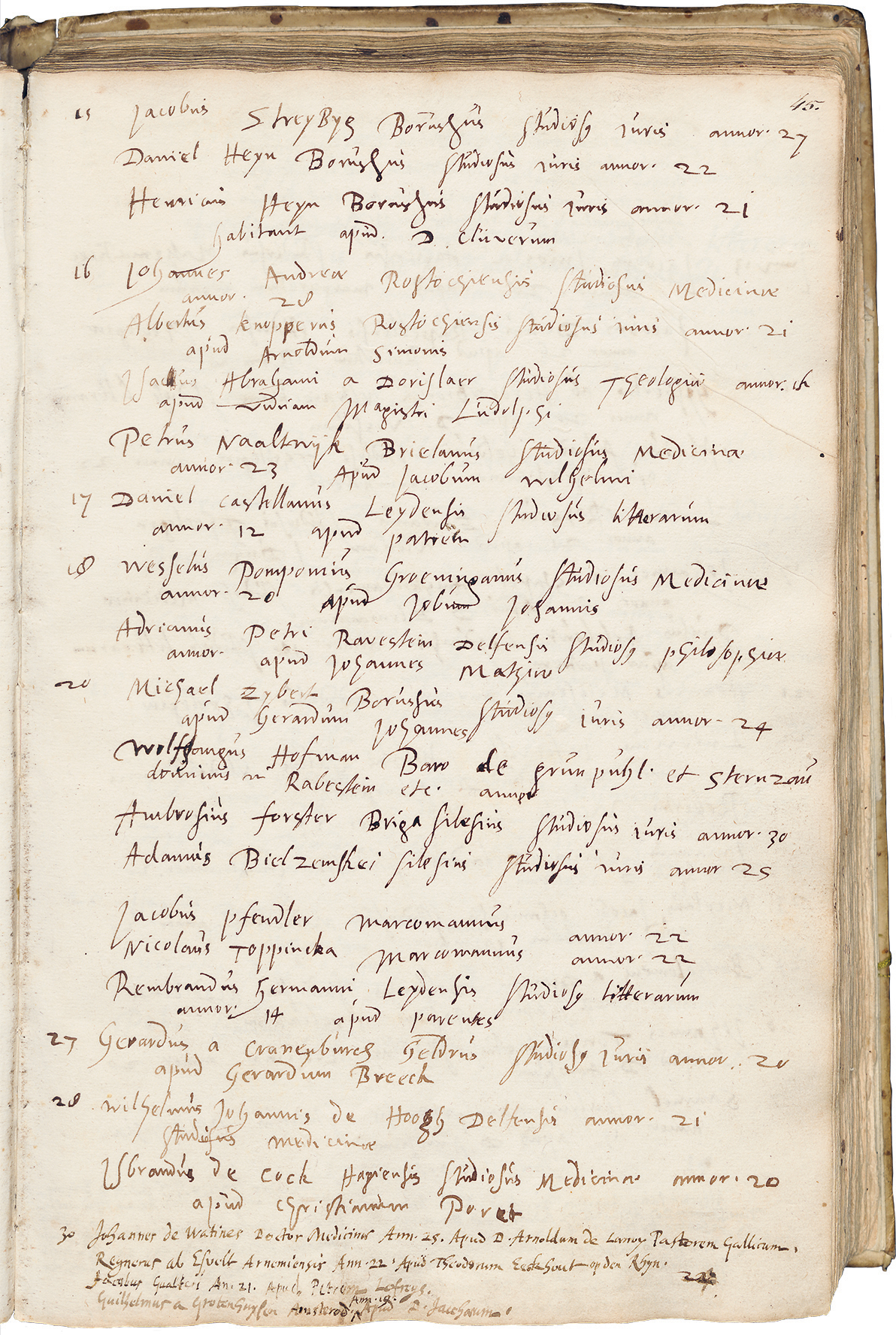

The monogram echoes the first written evidence of Rembrandt’s existence. On 20th May 1620 he enrolled as an arts student at the university. He was fourteen years old and living with his parents: “Rembrandus Hermanni Leydensis, studiosus litterarum annorum 14, apud parentes.”

Rembrandt attended the Latin school, studied for a time and decided at a relatively late stage to become a painter. It was not until he had spent two years at the university that his father apprenticed him to a local master. But from his very first day as an apprentice, he threw himself into his art with boundless energy. He adhered to the maxim of Apelles, the greatest painter in antiquity, who could enchant and deceive humans, and even animals, with his brush: “Nulla dies sine linea.” Not a day without a line drawn.

Ambition and enthusiasm gave him wings. When Constantijn Huygens, secretary to the stadtholder, Frederik Hendrik, and a connoisseur of art, visited Rembrandt’s Leiden studio in the spring of 1629 and saw the history painting Judas Returning the Thirty Pieces of Silver on the easel, his mouth fell open with astonishment.

“I maintain,” Huygens wrote excitedly in his memoirs, “that no Protogenes, Apelles or Parrhasius has ever produced, nor ever could produce even if they were able to return to this world, what has been achieved by a young man, a Dutchman, a beardless miller, in a single human figure and depicted in the totality [of the painting]. I stand amazed even as I say this. Bravo Rembrandt! To have brought Troy—indeed, all of Asia—to Italy, is a lesser feat than to capture for Holland the highest title of honour from all of Greece and Italy—and this by a Dutchman who has scarcely ventured beyond the walls of his native city.”

In the late 1620s, Rembrandt developed at lightning speed. And over the next four decades he would garner fame—not just in Leiden, Holland or the wider Dutch Republic, but throughout Europe. The monk and art lover Gabriel Bucelin, from southern Germany, listed Europe’s leading painters in 1664. The connoisseur enumerated 166 painters, including Titian, Leonardo, Tintoretto, and from his own age Poussin, Rubens and Van Dyck. Beside just one of these names, that of Rembrandt, he scribbled an addition—“Nostrae aetatis miraculum”, the miracle of our age.

So how did a miller’s son from a provincial city in Holland, born at the dawn of the seventeenth century, become one of the most famous painters in the world?

Volumen inscriptionum, 1618–31.

Very little is known about the young Rembrandt. From his boyhood days in Leiden—in contrast to his Amsterdam period—only a few dozen documents have survived: entries in administrative registers (bonboeken) relating to his family, the house and the mill, records relating to the neighbourhood in which he was raised, and notarial instruments. We have not a single personal letter, diary or notebook. Possibly none ever existed. The most intimate part of him that remains is his work.

Rembrandt is a mystery like Shakespeare, who also had neither influential family members nor an inherited personal fortune, and did not attend university. Yet Shakespeare conjured from such humble beginnings plays and sonnets teeming with intellectual and popular allusions that amaze the world to this day.

Notwithstanding his mythical status, Rembrandt was not always held in such high esteem. In fact, just before his death in the autumn of 1669—alone and destitute, in his rented apartment on Rozengracht in Amsterdam—the roughly painted work of his later years went out of fashion. His contemporary Gérard de Lairesse described Rembrandt’s work as “liquid mud on the canvas”, and referred sneeringly in his Treatise on the Art of Painting to the painter’s “splotches”. Arnold Houbraken wrote of Rembrandt, in his lives of the Dutch artists (De Grote Schouwburg der Nederlandse kunstschilders en schilderessen), that “close up, his paintings looked as if they had been laid on with a trowel”. Houbraken, a pupil of Samuel van Hoogstraten, who himself had studied with Rembrandt, relates that if visitors came to the master’s studio, he would tug people away who peered too closely at his pictures, saying: ‘The smell of the paint would bother you.’

He was said to have painted a portrait that was so heavily impastoed “that you could lift it from the floor by its nose”. “Thus you see also gems and pearls on jewels and turbans that are painted in such a raised manner that they look as if they have been modelled, a way of handling his pieces which makes them look strong even seen from afar.” With this latter remark Houbraken defends Rembrandt in a manner of which the master himself would have approved. In a letter of 27th January 1639 to Constantijn Huygens, enclosed with a painting offered as a gift to ingratiate himself with the stadtholder’s secretary, Rembrandt had written: “My lord, hang this piece in a strong light and where one can stand at a distance, so that it will sparkle at its best.”

After a visit to the artist’s studio, the secretary to Prince Cosimo, later Grand Duke of Tuscany and a passionate art collector, jotted down in an entry for 29th December 1667 in his travel journal that Rembrandt was a “pittore famoso”. In these notes, he used the adjective famoso for only two other artists: Gerrit Dou, Rembrandt’s “sorcerer’s apprentice”, and Frans van Mieris, the “prince of the pupils” of Dou. In their day they were the most popular and most expensive painters in the whole of Europe—and they never left Leiden, the city of their birth.

The academic theorists of the mid seventeenth and mid eighteenth centuries reviled him. They preferred the classical, fine, smoothly painted style that was perfected, ironically enough, by Rembrandt’s own Leiden pupils.

In the nineteenth century, Rembrandt was rediscovered. The influential critic and collector Théophile Thoré-Bürger (writing under the pseudonym of William Bürger) described the painter in his Musées de la Hollande as “mysterious, profound, and intangible”. Compared to Rembrandt, said Thoré, Gerrit Dou was nothing but a slick conjurer.

After Belgium’s secession in 1830, the Netherlands needed an icon, a Protestant national hero as a counterpart to the elegant Catholic artist Peter Paul Rubens. In 1852, a statue was erected in a square in Amsterdam, in honour of the miller’s son from Leiden. He embodied the nation’s ideals. Rembrandt took on the identity of the Netherlands.

In 1882, the much-feared critic Conrad Busken Huet called his history of the Netherlands Het land van Rembrand—“The Country of Rembrandt”. Huet depicted the painter as the cleverest Dutchman who had ever lived, and urged historians to emulate his style: this meant writing “with many omissions, much exaggeration, and [shining] a great deal of light onto a handful of facts and motives”.

Rembrandt’s gift, his “cleverness”, can be inferred not only from his exuberant style, his colours or his chiaroscuro, the dramatic effect of light and dark. His work is technically astounding, but above all it radiates the felt life. Spontaneous, authentic. True and real. That is the sensation that communicates itself to many who come face to face with one of his portraits: the quality of humanity.

Take the portrait that Rembrandt made of himself around 1628, at the age of twenty-two. A tiny panel measuring 22.6 × 18.7 cm, barely larger than this book. In the first half of the twentieth century it hung in a barn in Bearsden, a hamlet in the vicinity of Glasgow. Mary Winter, who had inherited it from her grandfather, had heard it said that the portrait was a genuine Rembrandt and assumed that it was a joke. She had once put the little painting up for sale in Scotland, but no one had displayed any interest.

In 1959 the portrait was purchased at a London auction by the art dealer Daan Cevat and subsequently transferred to the Rijksmuseum. In Amsterdam it initially commanded only lukewarm enthusiasm. Experts remarked on its strong resemblance to the self-portrait of Rembrandt in the collection in Kassel, but the latter was deemed more expressive.

Since then, the Rembrandt Research Project has performed an exhaustive analysis that proves that only the portrait in the Rijksmuseum is in fact a “genuine” Rembrandt. From scans it is clear that the painter was experimenting, as was his custom. The contours of the underlying sketch do not correspond exactly to those in the top paint layer. In contrast, the small portrait in Kassel was painted without any such corrections. It was most probably painted by a pupil after the original.

Today, we may find it almost impossible to comprehend that Rembrandt’s portrait was not immediately recognized as a masterpiece. If you take a step back and look at that young man, you are overcome by a sense that you know him. Indeed, you don’t just know him but feel what he is feeling. Although his eyes remain in the shadows, no more than two chasms into which your gaze vanishes, the image fills itself with Rembrandt’s imagination. You are close to him.

Rembrandt’s self-portraits are windows into his soul. They confront us with the imperfection of human existence and the inevitability of what will come. They convey an air of melancholy.

It was the film director Bert Haanstra, in Rembrandt, Painter of Man (1957), who first conceived the brilliant idea of placing a whole series of the master’s self-portraits one after the other, starting with the portrait of the boy wearing a gorget—the metal collar of a suit of armour—in 1629 and ending with the self-portrait of 1669, the year of Rembrandt’s death.

Each painted face merges with the next. They show Rembrandt ageing, his hair going grey, his wrinkles deepening and his face becoming fat and puffy. The bags under his eyes droop heavily. Gazing at the succession of images, I have the sense of looking into him. As if it is not just the artist’s life but my own that is playing out before my eyes like a film.

Despite all this, it is questionable whether Rembrandt saw his self-portraits as chapters of his intimate autobiography. The word “self-portrait” did not exist in the seventeenth century; it is a nineteenth-century coinage that became synonymous with Romantic self-expression. In the painter’s own day, such a likeness was called “a portrait of the painter by himself”.

Furthermore, not all self-portraits were intended to be likenesses. Rembrandt painted a great many tronies, facial types. Tronie was the seventeenth-century word (originating from French) for a head or face, but in the art of painting it was used to denote a specific character or type: a wrinkled old man or a charming young lady, an Oriental or a member of the civic guard. The 1628 portrait, in which the shadow falls mask-like over his eyes, must have been first and foremost a study of light and dark. An experiment. As a history painter, Rembrandt had to give each of his figures a different position in relation to the light, and wanted to know exactly how that looked.

In this small painting he tried to ascertain, seated in front of the mirror, how light falls on the face from an oblique angle behind the figure. Light grazes the jaws, the fleshy earlobe and the tip of his bulbous nose. Light plays around the curls in his neck, which have again been scratched into the wet paint with the back of the paintbrush. The eyes remain sunk in the shadows.

Are we looking into his soul here?

That is how it feels. However, that will not have been his primary aim. For his experiment, the painter chose his most patient model—himself.

When writers set about fathoming the mystery of Rembrandt, they are bound to seek parallels between the master’s work and his life. Some end up conflating the two. “His extravagant style of painting corresponded to his way of life,” wrote the Florentine biographer Filippo Baldinucci in his Vita di Reimbrond Vanrein (1667).

According to Baldinucci, the master was a vulgar oaf. “He was as sullen as he could be and did not care a fig for anyone else.” Rembrandt paid no attention to his appearance and mixed with people below his social class. The “ugly and plebeian face [una faccia brutta e plebea] by which he was ill-favoured, was accompanied by untidy and dirty clothes, since it was his custom, when working, to wipe his brushes on himself.”

Baldinucci’s gibe was intended to show that the master’s late work was much of a muchness with his appearance: low-class and slovenly. It is a curious misconception. There is no logic in suggesting that a slob will paint messily. You might just as well turn the artistic myth on its head: Rembrandt did not care a fig for anyone else, paid no attention to his appearance or to etiquette, because he was obsessed with his work. That is why he was such a superb painter.

Still, one of Baldinucci’s points does hit home: if you look at the portraits that Rembrandt made of himself from the mirror, you cannot possibly claim that he was a handsome man. Certainly, he possessed a robust kind of charm, but he had a bloated, pockmarked face and a huge, bulging nose.

This becomes clear from the self-portrait that he made perhaps just a few days after the one in which he had painted his eyes without a gleam of light. Judging by the memories of Constantijn Huygens, Rembrandt then looked more like a child than a young man. Here he has the appearance of a truculent teenager. His lips are parted in a slightly gormless expression, as if he is exclaiming to his father: “Oh! You here too?”

Self-portrait, Bare-headed, 1629.

Self-portrait in the Mirror, c.1627–28.

The first blond and dark hairs of his emerging beard are just poking through the skin. On his stubbly chin are two shiny pimples.

Why did Rembrandt depict himself with such brutal honesty? This portrait is one in a series of paintings and etchings in which he experimented with rendering emotions. He showed himself laughing, sombre, stern, in pain. And in each of these likenesses he cast the shadow over his face in a different way.

This is Rembrandt’s first life-sized portrait of his face. To achieve it, he worked at a short distance from the mirror—quite literally, close to the skin. He wanted to explore ways of rendering human skin as naturally as possible—the colour, the structure of the pores. How does a pimple, or a single hair in a man’s beard, catch the light?

The uncompromising honesty with which Rembrandt captured his uncouth face is above all a mark of courage. He disdained outward show and did not seek to erect a vainglorious monument to himself. His striving transcended all such aims: he did not paint an ideal, but “nature”.

He saw beauty in ugliness.

Joachim von Sandrart, the German painter and writer whose years in Amsterdam were spent in the shadow of the great master, scoffed in his Teutsche Academie that Rembrandt always insisted “that one must be bound only by nature and by no other rules”.

The suggestion by Baldinucci and Von Sandrart that he just “messed around”, as the modern Dutch master Karel Appel once described his own method, is quite wrong. The ostensibly simple assertion that Rembrandt painted from life, as did Leonardo and Caravaggio, contains a paradox: in the depiction of reality, he showed himself to be a master of illusion.

The verdict on Rembrandt—over four centuries, a whole library has been devoted to him—is often more about morality than art. Starting in the nineteenth century, a petty-bourgeois philosophy distorted the vision of his life and work. Since Rembrandt had been declared a genius, his character and conduct were expected to accord with this; his life must be a devout, righteous epic. The word “genius” invariably deals a death blow; it erases the human being behind it.

Carel Vosmaer, the first biographer of Rembrandt to base his work on historical documents in Leiden’s archives, contrived to present an idyllic picture of the master’s life. Human frailties were omitted. Much soil was left unturned. In an epilogue to the Dutch translation of Christopher White’s biography (1961), we find the first reference to the fact that after Rembrandt quarrelled with his housekeeper Geertje Dircx, with whom he had had an affair and then fallen out over money, he arranged for her to be confined to the Spinhuis correctional institution in 1650. Even then, these sordid details were squirrelled away at the back of the book, in a small font.

By now, virtually every drop of paint from Rembrandt’s brush, every panel and every thread of linen from his paintings, has been subjected to laboratory tests. The work of the Rembrandt Research Project has generated a wealth of information about the painter’s methods. The six thick volumes of A Corpus of Rembrandt Paintings constitute an indispensable source. Hundreds of facts in his life have been retrieved from the archives and compiled in the superb Rembrandt Documents.

On the rebound from the image of the flawless genius, the past few decades have produced an entirely different picture of Rembrandt, based on facts from his later years—the episode with Geertje, the writ of cessio bonorum in which he relinquished all rights to his goods, and the application for bankruptcy that was submitted to the burgomasters of Amsterdam on 14th July 1656, a day before his fiftieth birthday. This revised picture was of a scoundrel and a spendthrift.

Could that, perhaps, be a rudiment of the Romantic notion that a real artist has a dark soul? His name is invoked to demonstrate the truth of the traditional Dutch proverb: “The greater the spirit, the greater the beast.” And the painter Karel van Mander, the author of the Schilder-Boeck, commenting on his fellow artists, quipped acidly that in the popular imagination, “Hoe schilder, hoe wilder”—roughly, “The truer the painter, the wilder he is.”

Was Rembrandt wild? Let us start from the bare, indisputable fact of his existence. Then, in our quest to find out who he really was, we will need to look very closely at many things. At his work, to begin with. At the way in which he communicates with us through his imagination. But to get a picture of his childhood, we must look around the Dutch Republic that was under construction, the city, the alley and the house in which he was born and bred.

Did Rembrandt’s brilliance spring from the genius loci, the spirit of Leiden? Can it be traced to his family, his teachers, clients, rivals, fellow artists and friends? Or was his development a highly personal, idiosyncratic adventure?

How did Rembrandt become Rembrandt?

That is the question.