FROM THE AGE OF FIVE, REMBRANDT’S EARS WOULD HAVE RUNG WITH the daily cacophony of hammering and sawing drifting across the River Rhine. Turning out of Weddesteeg towards the river, he would have seen the craftsmen and labourers in the main carpentry yard on the other side of the river hard at work building the new city. Huge oak logs were imported from the Baltic States, hoisted onto the wharf and sawn to size. Cobblestones, solid black round stones for the street, and bricks for houses, walls and quaysides were piled up and trundled away in carts and barrows. The yard was a construction site for a boom town.

The 1574 relief of Leiden had attracted a sheer endless flow of immigrants. Leiden’s successful stand for liberty had made it an appealing destination for religious refugees from Germany, England, France and Flanders. The city council welcomed them with benevolent enthusiasm. During the siege, famine and Plague had decimated the city’s workforce, as a result of which the city’s cloth trade, mainstay of the city’s economy, had shuddered to a standstill. New blood was vital to the city’s revival.

In 1577, Jan van Hout journeyed to Colchester, in the English county of Essex, to recruit workers among the communities of Flemish and Walloon refugees who had settled there. Van Hout offered them the prospect of housing, freedom of religion and burgher status free of charge. He returned with groups of dyers, carders and sheep-shearers in his train.

The largest contingent of refugees came from the Southern Netherlands. In 1582, the major textiles centre of Hondschoote in French Flanders fell to Spanish troops. And from Ypres and Poperinge in West Flanders too, hundreds of Protestants fled to Leiden. The fall of Antwerp, on 27th August 1585, after an exhausting, year-long siege by troops led by Alexander Farnese, the Duke of Parma, triggered a fresh influx of immigrants.

In the spring of 1609, a group of Puritans, Calvinist dissenters from the Church of England who feared repression under King James I, sought asylum in Leiden. The separatists stayed close together, living in the shadow of the Pieterskerk. Their minister, John Robinson, preached in private homes and became embroiled in fierce theological debates at the university. The former Cambridge undergraduate William Brewster printed their dissident books on the group’s own press. Most of the Puritan community, however, toiled for a pittance in the cloth industry.

Life in Leiden was onerous for the newcomers. Not only because of the hard work, but primarily, in a curious stroke of irony, because they saw the religious liberty on the basis of which they had been given sanctuary as posing a threat. The Puritan refugees feared that the lax views of many of the locals—who allowed their children to play freely in the street and who kissed them goodnight at bedtime—set a bad example to their own children. They were afraid of assimilation.

In 1620 some of the Puritans decided to leave Leiden. These Pilgrim Fathers crossed the Atlantic in the barely seaworthy Mayflower, eventually disembarking at Plymouth, New England. They would come to be seen as the founding colonists of the United States. Some of their customs and habits derived from their time in Leiden. The festivities held to mark their first harvest, in the autumn of 1621, have endured to this day: the feast of Thanksgiving may have its origins in Leiden’s annual celebrations on 3rd October.

Leiden was bursting at the seams. There was an acute lack of homes for the thousands of immigrants. The city council and private individuals initially sought to solve the housing shortage by partitioning houses and rapidly filling gardens and open spaces around the city with new dwellings. It even ordered houses to be built against the city walls.

The Nazareth convent in Maredorp, a settlement to the north of the castle that had been incorporated into the city in the fourteenth century, had been dispossessed by the Protestant city council after the outbreak of the Revolt. In the courtyard of the old convent, sixty-three cottages were built back to back in 1596 to accommodate weavers: social housing avant la lettre. But the tiny homes were so cramped that the residents of Maredorp nicknamed the old convent “the Anthill”.

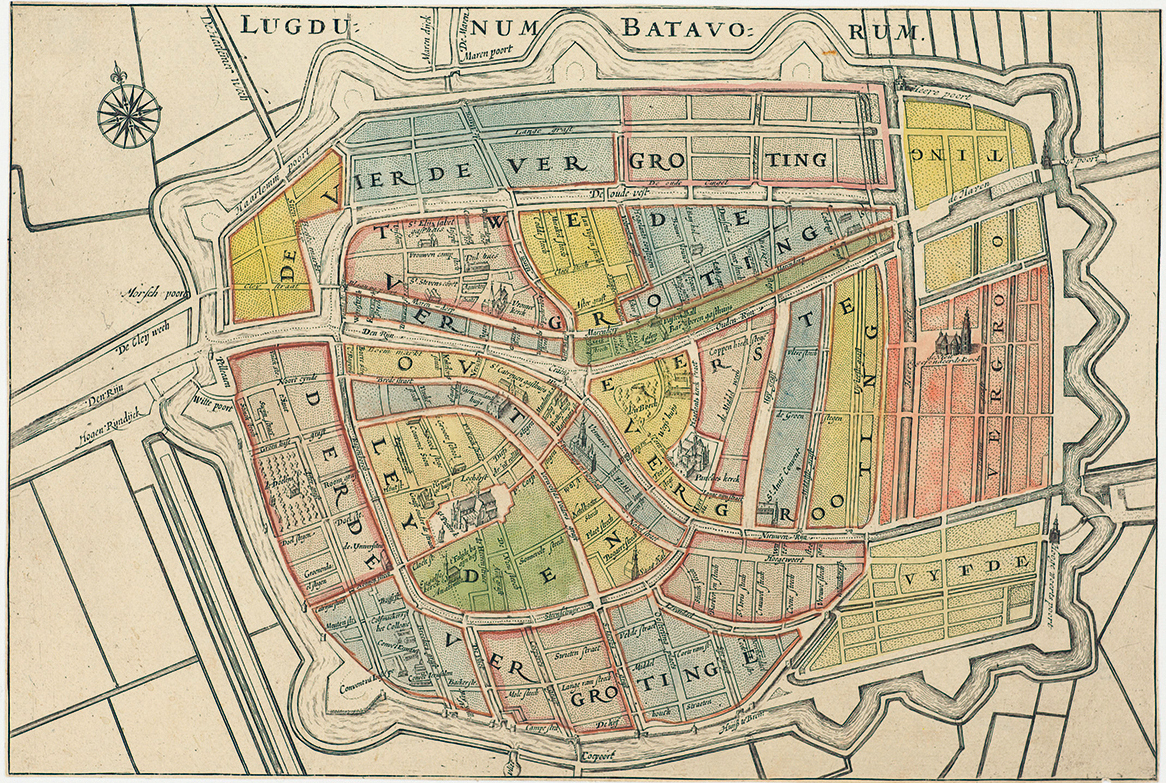

In 1611, after long prevarication, the city council gave its consent for the “Fourth Expansion”, designed by the surveyor Jan Pietersz Dou, as a result of which Leiden acquired a huge swathe of land to the north. A year after work began, Rembrandt’s parental home no longer stood in a blind alley: the road had become a busy thoroughfare. The little archway at the end of Weddesteeg had gone, the old ramparts had been torn down and the inner canal around the corner had been filled in.

A long wooden bridge spanned the river, leading to “the land of promise in the new city”, according to a memorial plaque in the wall of a corner house at Beestenmarkt, the cattle-market square. The tablet depicts two men carrying two huge bunches of black grapes hanging from a pole resting on their shoulders. With the new city came a prolific new harvest.

Rembrandt would have crossed the bridge over the Rhine with his father and siblings, roamed the streets and along the canals, over bridges and the triangular cattle market, gaping at the transformation. Not so long before, this area had been full of wide expanses of market gardens, fields with grazing cattle and flowering apple trees.

The structure of the network of waterways and roads would have astonished him. It was worlds apart from the medieval labyrinth of the city centre. Dou had used a ruler to mark the contours of the “Fourth Expansion”, and the digging and building had adhered faithfully to these lines. A totally straight canal, aptly named Langegracht (“Long Canal”), extending east–west across almost the entire width of the city, with wharves on either side, was crossed at regular intervals by smaller, equally straight canals for drainage, such as Oostdwarsgracht and Westdwarsgracht. In between were rectangular plots of land, with blocks of labourers’ dwellings, dyeworks and fullers’ workshops in a mathematical pattern.

Jan Pietersz Dou, map of the waves of expansion of the city, 1614.

The new city was built not only to alleviate the acute housing shortage, but also to drive the cloth industry out of the city centre. Decades earlier, in 1591, Jan van Hout had issued an alarming report on the pollution of the canals caused by the textile industry: fullers and dyers freely discharged a mixture of uric acid and dye into the water. Marcus van Boxhorn’s 1622 description of the cities of Holland (Toneel ofte Beschryvinge der steden van Hollandt) praises Leiden as “celebrated for cleanliness”. Yet the city must nonetheless have been pervaded by a fearful stench, especially on hot days.

With the new expansion, fullers’ workshops could move out of the centre to the outermost canals. An ingenious system was invented to pump the filthy water in Volmolengracht out of the city as rapidly as possible through the vuilsloot—“waste ditch”. Whatever the stench, and however inhospitable the living conditions, the transformed surroundings must have held an almost surreal fascination for Rembrandt. The water in the canals would turn cobalt-blue or vermilion, according to the dye being dumped in it. On dry, sunny days, flakes of sheep’s wool drifted through the air and covered the streets like snowfall.

Rembrandt will also have been struck by the strangeness of the language being spoken all around him: a mixture of French and Flemish that would end up enriching Leiden’s vernacular. To this day, the city’s local dialect has the soft, sing-song intonation of Flemish and a rolling “r” sound. Lists of local residents abound with French names—Labrujère, Laman, De la Court, as well as literal translations such as Schaap (Mouton), De Wekker (Reveillo) and Kwaadgras (Malherbe) and bastardized forms such as Wijnobel (Vignoble).

Besides manpower, the immigrants also brought new skills and a knowledge of innovative techniques. Since the fourteenth century, Leiden had been producing thick cloth from English wool and selling it to the Hanseatic cities. With the outbreak of the Dutch Revolt, that market had collapsed. The Hanseatic cities lost their strong grip on trade and the thick cloth in traditional colours went out of fashion.

The refugees from the Southern Netherlands possessed a different kind of expertise: they were expert at producing lighter materials, made of thin worsted yarn—or combinations of worsted with silk, cotton or goat’s wool: saai, baize and bombazine. The city council gave permission for the production of the “new draperies”, made from wool from Dutch sheep, and more frequently still—in spite of the war, strangely enough—wool imported from Spain.

The quality of the new fabrics was not inspected by a guild but indirectly by the city council itself through trading companies known as neringen that were responsible for part of the cloth production. The leading production centre was the Saaihal, whose premises were the former St James’s Hospital (Sint-Jacobsgasthuis) on Steenschuur. Isaac Claesz van Swanenburg, one of the city’s leading artists, won the commission to depict the various neringen in large panel paintings for the walls of the privy chamber in the Saaihal, where the governors held their weekly meetings.

Six of Swanenburg’s paintings have survived. Two depict allegorical scenes: in one, we see the Maid of Leiden gently supporting the Old Nering, an elderly woman clad in drab, heavy materials. Around them are cherubs, the central one having a conspicuously empty purse. With her open left hand, the Maid of Leiden welcomes the New Nering, a young woman dressed in supple, light-coloured garments. She flies in on the arm of Hermes, the messenger of the gods, who lands gracefully but forcefully on the earth, flattening the scythe of Time.

In the second allegorical painting, the Maid of Leiden hands a book of hallmarks to a woman who has the words “DIE NERINGHE” embroidered in gold letters on the seam of her dress. This painting depicts both the new production method and the way in which the city council monitored and administered the quality of the new cloth. The purse of the little cherub who accompanies the woman is now full.

Oddly enough, Van Swanenburg chose to paint himself and his fellow local officials standing on an imaginary balcony. Moreover, the city in the background of his paintings presents a baffling appearance. His Leiden is endowed with a range of fictional elements and has been portrayed quite clumsily. For this scene, he could have chosen to depict the platform at the top of the steps to the town hall’s brand-new façade.

In 1597, the city-appointed stonemason Claes Cornelisz van Es furnished the medieval town hall with a long, sandstone façade. Its design, by the architect Lieven de Key—a refugee from Flanders—abounds in allusions to the siege and relief of Leiden. Two bluestone plaques bricked into this façade—one of which was an old altar stone from the Pieterskerk—were inscribed with lines of verse by Jan van Hout. One contains a numerical riddle or chronosticon that yields the number “1574”, while the other urges the people of Leiden not to allow affluence and good fortune to tempt them into pride.

The prosperity came from elsewhere: the people of Leiden knew that all too well. The Oriental patterns carved at intervals into the stone conjured up associations with the Alhambra. The most outlandish additions were the copper crescents balancing on pointed cones atop a long row of stone balls. The crescent moons were an allusion to the motto of the Sea Beggars: “Better Turkish than Popish.” Leiden’s Calvinists saw conversion to Islam as a lesser evil than embracing Roman Catholicism.

In the four remaining paintings, Van Swanenburg provided synoptic images of the cloth-production process, akin to those of a comic strip. In the first painting, large bales of fleeces are imported into Leiden, after which the wool is washed in the canal and sorted. In the second painting, raw wool is spun into yarn; we see the wool being loosened from the sheepskin by hand and with the shears. Next, vlakers beat the coarse dirt from the wool, using a stick or their hands, and smouters grease the wool with oil or melted butter until it is smooth and flexible, ready to be combed.

The third painting shows the process of spinning with the “Big Wheel”: the beaming of the warp, the winding of the yarn onto the bobbin, and the weaving process. Many Leiden weavers had their own looms at home: the loom would occupy almost the entire living room. The centre of the wool trade was at the aptly named Garenmarkt (“yarn market”), a square in the southern district, just over the bridge near the Saaihal. This was where weavers sold their wares. Many were self-employed and were compelled to work for a pittance.

The fourth painting shows the fulling and dyeing of the wool. The saai had to be cleaned and degreased. The fullers stamped on the material in large wooden tubs filled with a mixture of soil, urine and soap, until it was soft and felted. The long pieces of cloth were then rinsed in the canal. The fullers would hang the cloth up on a frame between posts, so that it would maintain precisely the right length. Each section had to be between thirty-six and forty ells long—roughly twenty-five metres.

Next, the cloths would be immersed in a warm bath and dyed black, blue, ochre or red. In the final stage, the sampling officials or “syndics” would check the product’s quality by cutting a tiny strip from the fabric as a sample and matching it against earlier samples of high-grade cloth. If the new cloth passed muster, the syndics would affix a hallmark in the form of a slug of lead with the crossed-keys imprint.

Leiden’s lead discs served to guarantee quality, and the syndics were seen as the custodians of the city’s reputation in the world. This authority shines through in the group portrait that Rembrandt made in 1662 of the five syndics of the Amsterdam Drapers’ Guild and their servant. For a Leiden boy, it was a familiar picture. Similar group portraits for syndics were commissioned at the same time in Leiden. They were hung in the splendid, majestic Lakenhal that had been built in 1640 in the middle of the Marewijk quarter by the city architect Arent van ’s-Gravenzande.

In the case of the Amsterdam group portrait, all the men depicted here have been identified: apart from the servant, they are two Catholic cloth-buyers, a Mennonite (a follower of the religious leader Menno Simons) cloth-buyer and art collector, a Remonstrant patrician and a Reformed Protestant from a prominent family. Only in the Dutch Republic would you have found such a diverse group sitting around the table together in the seventeenth century in such a spirit of congeniality. “Look at the syndics,” wrote the Leiden historian P.J. Blok in 1906, “are they not Dutchmen through and through, distinguished citizens, imbued with a sense of duty and their weighty task?”

Isaac Claesz van Swanenburg, Washing the Skins and Grading the Wool, 1594–96.

Isaac Claesz van Swanenburg, The Removal of the Wool from the Skins and Combing, 1594–96.

Isaac Claesz van Swanenburg, Fulling and Dyeing, 1594–96.

Isaac Claesz van Swanenburg, Spinning, Cutting the Warp and Weaving, 1594–96.

It is fascinating to see how Rembrandt managed to spin such a dull commission into a captivating scene. He uses a theatrical trick: he paints the moment at which an unsuspecting viewer suddenly enters the room. Without knocking. One of the syndics rises from his chair, another falls silent mid-sentence, a third stops leafing through the book of hallmarks. In concert, the syndics turn their gaze on us.

The inspectors of the Amsterdam Clothmakers’ Guild, known as The Syndics of the Drapers’ Guild, 1662.

Rembrandt has left the real reason for the syndics’ meeting—the cloth to be inspected—out of the picture. The dark-blue or black strips are laid out on the table, but we cannot see them. We are denied a view of the table because of the low perspective chosen by Rembrandt. He knew that the painting was going to be hung high up on the wall of the Amsterdam Drapers’ Guild Hall, the Staalhof.

Even so, Rembrandt could not resist the opportunity to display his gift for painting fabrics. The light catches the edge of the table, which is covered with a precious Persian rug. Rembrandt did not elaborate the rug’s pattern in delicate detail using a sable brush; instead he daubed, smudged and stamped. The rug flares with colour. In Rembrandt’s hand, paint becomes material.

The cloth trade provided chances for weavers, fullers and dyers to build new lives in Leiden. It also abounded in investment opportunities, and speculation was rife. Any resident of Leiden who had any capital purchased plots of land, built houses on them and rented them out. So too Rembrandt’s father. In 1614, Harmen bought a large plot, around the corner from the Weddesteeg. He built five dwellings on it, moved relatives into them and rented out rooms. To collect the rent due, he simply walked down the alleyway that led from his backyard to the water—a passage built for this very purpose.

The fact that Harmen was able to make this investment shows that he was a decidedly affluent man. That is confirmed by the last will and testament that Rembrandt’s parents had drawn up on 16th February 1614. When Harmen van Rijn received a demand in 1623 for payment of the 200th penny—Leiden city council had levied 0.5 per cent tax on the estimated assets of its burghers, since every city in Holland had to contribute to the Republic’s war chest—he was assessed for a bill of forty-five guilders, which he managed to get reduced to thirty-five guilders after a “reassessment”. Even so, this means that his assets were assessed at a value of 7,000 guilders.

When Neeltje died in 1640, ten years after Harmen, and the couple’s assets had to be divided among the four surviving children, the estate was valued at a good deal more: including household effects and a grave and a half in the Pieterskerk, it came to 12,000 guilders.

This was a very substantial sum of money. It is hard to calculate precisely what value this represented in today’s terms, given that both the currency and purchasing power were subject to fluctuation, but we can multiply that sum by at least 100—perhaps 200. In 1640, a carpenter’s salary was no more than one guilder a day.

The miller’s family was flying high.