WHY DID REMBRANDT DROP OUT OF HIS COURSE AT LEIDEN UNIVERSITY? Was he a wayward young man who baulked at the discipline of academia? According to Orlers, his parents were compelled to remove him from university “since his natural inclinations were exclusively to the arts of Painting and Draughtsmanship”.

It cannot be denied that Rembrandt was a rebel, but his decision to abandon his studies should also be seen in the context of wider historical events. In 1618, strict Calvinists known as Gomarists or Counter-Remonstrants seized power in the city, ousting the broader-minded Arminians or Remonstrants from positions in the town hall and banishing the spirit of Erasmus from what had been the bastion of liberty. That will have made it difficult for Rembrandt to continue his studies in the arts.

Rembrandt was raised in a Remonstrant family. He and his parents went to the Pieterskerk, which had been plucked bare by the depredations of the Iconoclasm, and heard the minister’s voice and the psalms echoing through the hollow space between the columns. He would not have been allowed to sing in the choir, as the pupils of the Big School had once done every Sunday. Although the Van Rijn family attended Reformed Church services, his mother and her family, as well as his father’s family, all remained Catholic. In any case, they were far from literalists.

The Van Rijn family moved in latitudinarian circles. The family’s notary was Adriaen Claesz Paets, the leader of the Remonstrants. The membership list of the Remonstrant congregation, which would not be drawn up, for reasons of security, until the 1650s, included Elisabeth Simonsdr and her daughter Cornelia, the widow and daughter of Rembrandt’s brother Adriaen. Rembrandt himself was never a registered member of either the Remonstrant or the Calvinist congregation—not in Leiden, nor later in Amsterdam.

He did not openly profess any specific denomination, doubtless seeking to avoid alienating potential clients, whatever their religious beliefs. He retained an air of neutrality. Indeed, he depicted himself in 1661 as St Paul, the Apostle who warned the early Christians about sectarian tendencies in his Epistles to the Corinthians. St Paul did not distinguish between winning the hearts of Jews, Christians, humanists and those of no faith at all. He wrote (I Cor. 9:19): “For though I be free from all men, yet have I made myself servant unto all, that I might gain the more.”

Self-portrait as the Apostle Paul, 1661.

Yet the religious climate in which Rembrandt grew up was marked by growing intolerance. The seizure of power by the strict Counter-Remonstrants cut off the path to the possible careers his parents had envisaged for him. With his religious background, he could bid farewell to any hopes of becoming a public administrator, an academic or a physician. Most undergraduates followed in their fathers’ footsteps.

The best opportunities for acquiring a good position in society were in the largest faculty: theology. Rembrandt’s magnificent paintings of biblical stories demonstrate his affinity with this branch of learning. However, following the power grab of the strict Calvinists, the study of theology must have lost its allure as a fount of knowledge. It was more like a desert.

The controversy that ultimately ripped apart the entire Dutch Republic found its origins on Rapenburg. It had started with a bold appointment. In 1603, the Amsterdam pastor Jacobus Arminius took up a chair in theology at Leiden University. His fellow professor, the Flemish-born Franciscus Gomarus, had expressed objections based on the newcomer’s reputation for a lack of orthodoxy.

On 7th February 1604, Arminius chaired a debate on divine predestination in the university’s auditorium. His liberal approach to the topic provoked Gomarus to react with a forceful denunciation. He organized an opposing debate, outside the university’s schedule, in which he proclaimed the importance of strict orthodoxy. From that time onward, the two theologians engaged in an open polemic.

Jacobus Arminius

Franciscus Gomarus

While Arminius reasoned that people were elected to salvation on the basis of their response in faith, Gomarus posited that the chosen received faith, and hence God’s grace. Arminius embraced the concept of free will, through which humans could earn themselves a place in heaven by doing good on earth. In the view of Gomarus, the faithful were accorded a place in heaven, a prospect reserved for very few following the Fall from grace in the Garden of Eden. Only God, he insisted, could determine the fate of a human being.

Salomon Savery (attrib.), The Scales, 1618.

It was said that Arminius and Gomarus fought out their battle not only in the lecture halls, but also across the hedge that separated their gardens on Nonnensteeg and Achtergracht. Their neighbours were astonished, the legend goes, to hear the two theologians hurling curses at each other in Latin. The colourful story is easily refuted, if only for geographical reasons. It is true that Gomarus owned a building on the south side of Nonnensteeg—it was there that he quarrelled with the university’s board of governors about the wall of the botanical garden that would block the light—but he rented that house out. Moreover, the gardens of the two scholars were not adjacent at all.

In reality, the dispute played out across the Rapenburg canal, where both professors resided in their elegant houses: Gomarus in a mansion now numbered 29–31 and Arminius (from 1608) on the other side, at number 48. The apocryphal story may have sprung from a misreading of two lines by the great Dutch poet Joost van den Vondel, in an anonymous satirical caption to the print On the Balance of Holland, which may be roughly rendered:

Gommer and Armijn in court

For the one true faith they fought.

The court referred to here is the Court of Holland. But the Dutch word hof means not only “court” but also “garden”—and it is possible that some misinterpretation could have led to the anecdote about the two professors shouting abuse at each other over the hedge.

Arminius died in 1609, but his death by no means buried the debate. On the contrary, a war of opposing pamphlets erupted between the Arminian Remonstrants and the Gomarist Counter-Remonstrants. In other Dutch cities, too, the issue of divine predestination provoked fierce debate. In 1610, dozens of Arminian preachers, led by Johannes Wtenbogaert, court preacher of Maurits in The Hague, drafted a petition to the States of Holland entitled the Remonstrance, setting out their positions in five articles. A year later, the Leiden church minister Festus Hommius drew up an opposing declaration affirming the beliefs of the Counter-Remonstrants in seven articles.

The Counter-Remonstrants were incensed that the Remonstrants had addressed their petition to secular rather than ecclesiastical authorities. Radical Calvinists regarded the Arminians’ positions as amounting to crypto-Catholicism—heresy. The conflict led to a schism within the Reformed Church in Leiden—the two groups held separate council meetings—and between the Church and the city council. The vroedschap consisted largely of Remonstrants from well-to-do local families, while among the population at large, especially among the large immigrant community, the stricter Counter-Remonstrants were in the majority.

Religious controversy is the theme of a painting that Rembrandt made around 1628, Two Old Men Disputing. A man with a long white beard, clad in a light-blue robe, is stabbing with the index finger of his right hand at a line in the book lying on the lap of another elderly man. The book is brightly illuminated.

The Apostles Peter and Paul Disputing, 1628.

The men depicted here are far from random individuals: they are the Apostles Peter, the tonsured figure we see from behind, and the bearded Paul. Rembrandt based the composition on a print dating from 1527 by Lucas van Leyden, which likewise depicts Peter and Paul in earnest debate. In Lucas’s print, it is Peter who points to the book rather than the writer and preacher Paul. Rembrandt’s Apostles are not martyrs but intellectuals. In this painting, he did not furnish them with their customary attributes—Peter with the keys to heaven and Paul with the sword with which he was murdered—but only with books.

Might Rembrandt have had Gomarus and Arminius at the back of his mind when he depicted the disputing old men? In any case, he worked in a city awash with bearded religious pedants. After the Synod of Dort, academics at the University of Leiden set about preparing a new translation of the Bible, which would be the Statenbijbel (“States Bible”). Every word was weighed and pondered. Is Paul’s pointing finger a covert allusion to the projected Statenbijbel?

The Leiden controversy spread across the map of the Dutch Republic like a giant ink blot. Prince Maurits decided in the summer of 1617 to side with the Counter-Remonstrants. That was striking, since he had previously confessed to a total ignorance of theology; indeed, he was quoted as saying that he did not know “whether predestination was green or blue”.

All the evidence suggests that Maurits’s choice was a pragmatic one. To preserve the unity of the state and to strengthen his own position, he adopted a more orthodox position than his father, who had tried to uphold the principle of freedom of religion until his death in 1584. Maurits thumped the hilt of his sword and said: “With this I will defend the religion.”

In siding with the Calvinists, Maurits found himself diametrically opposed to the legal adviser to the States General, the ‘Land’s Advocate’ Johan van Oldenbarnevelt, the most powerful man in the Dutch Republic. On 5th August 1617, Van Oldenbarnevelt issued a “strong resolution” that gave city councils the authority to hire mercenaries to restore peace and order.

When Maurits had first entered the political arena, at nineteen years of age, he and the Advocate established a fine rapport. They complemented each other: the wily politician who planned ahead and dared to take risks, and the prince who showed himself an able military leader at a young age, with a shrewd ability to strike at the right time. Together they formed an ideal combination of ingenuity and strength.

Their relationship deteriorated, however, when Van Oldenbarnevelt sent Maurits to the south, much against the prince’s wishes, to take the “pirate nest” of Dunkirk. The long expedition almost cost the prince his life, when Spanish troops cut him off and he was compelled to engage them in what became the Battle of Nieuwpoort in 1600. He barely managed to snatch victory from the jaws of defeat.

The relationship plunged to new depths after Van Oldenbarnevelt concluded a truce with the Spanish in 1609 to protect the cities of Holland from any further damage to trade and to contain the mounting costs of the war. Maurits fiercely opposed the truce. He feared that the Spanish would lick their wounds and then strike back with even greater ferocity. What he wanted most of all, however, was to maintain his position and income as a general. To carry on fighting.

The truce with the Spanish had the effect of turning the Republic in on itself, which at length triggered a new internal struggle. Resentments grew between the dominant province of Holland and the other provinces, and deep chasms opened up in matters of politics and religion. The egalité that William of Orange had tried his best to achieve was strained past breaking point and was being fought out in the streets.

On 20th September 1617, Leiden’s Remonstrant city council responded to Van Oldenbarnevelt’s “strong resolution” by hiring 200 mercenaries, who went about brutally suppressing dissent. It proved counterproductive. On 4th October, in the wake of the commemoration of the relief of Leiden, riots erupted. Rough-and-ready youths from Walenwijk threw stones at the town hall, and mercenaries chased the stone-throwers through the alleys on either side of Breestraat, trampling on innocent passers-by as they went. One old man was struck on the head with a halberd.

The city council was forced to call the civic militia to arms by way of reinforcements. Throughout the city, people shuttered their windows and barred their doors. The uproar would have penetrated the walls of the classroom where eleven-year-old Rembrandt sat studying, but he would not have joined in. He was not a street urchin and was certainly not given to throwing stones.

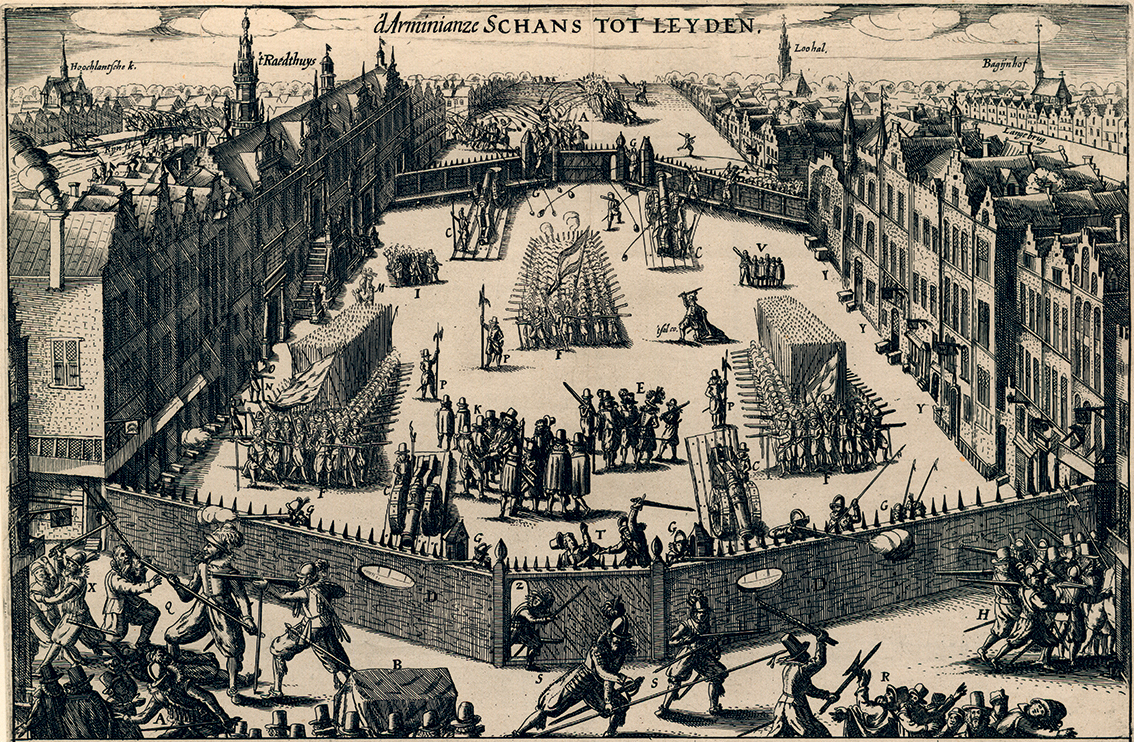

Fearful of the restive populace, the city council took action the next day, 5th October, to seal off Breestraat on both sides of the town hall. Two barricades of tall oak stakes were erected, capped with spikes that locals were soon calling “Oldenbarnevelt’s teeth”. The wooden structure itself was dubbed “the Arminian redoubt”, and later—after it had been torn down—a pamphlet distributed by the orthodox Counter-Remonstrants would personify it as “the Arminian tyrant” in lines that can be roughly rendered:

Anon., The Arminian Redoubt in Leiden, 1618.

The Arminian tyrant

Wrought havoc in this Land;

But now is he brought low,

His people no more are cowed.

Almost a year later, in the summer of 1618, Maurits decided to intervene. He dismissed all the mercenaries and disposed of his political opponents. He appointed new officials to executive positions. On 29th August he had Van Oldenbarnevelt arrested on charges of high treason, along with the Pensionary of Rotterdam, the liberal jurist Hugo Grotius, and the Remonstrant Pensionary of Leiden, Rombout Hogerbeets. Grotius and Hogerbeets were sentenced to “eternal imprisonment” by a bench of twenty-four judges. They were locked up at Loevestein Castle, from which the scholar Grotius escaped in a chest of books on 22nd March 1621. Hogerbeets was eventually released by the new stadtholder, Frederik Hendrik, in August 1625, following the death of Maurits.

Van Oldenbarnevelt met with a grimmer fate. After nine months in prison, the seventy-two-year-old advocate was brought before a court presided over by Reinier Pauw, the Calvinist burgomaster of Amsterdam, and sentenced to death. Van Oldenbarnevelt refused to request clemency, which he saw as an implicit acknowledgement of guilt. On 13th May 1619 he was beheaded on the scaffold at the Binnenhof in The Hague. To the crowds that had flocked to the scene, he declared: “Men, do not believe that I am a traitor to my country. I acted piously and with sincerity, as a good patriot, and that is how I shall die.”

While Van Oldenbarnevelt was being held in captivity, Maurits had been going from city to city to dismiss the mercenaries and to put in place a new Calvinist order. On 23rd October 1618, he and his troops entered Leiden. The Arminian redoubt was quickly dismantled and with the looming threat of the stadtholder’s presence, twenty-two members of the advisory vroedschap were replaced, along with all the magistrates and three of the four burgomasters.

With the aid of Jacob van Brouchoven, a strict Calvinist jurist who had hitherto adopted a minority orthodox position in Leiden city council, Maurits purged the city council of all its Remonstrant members. Van Brouchoven took his seat in the court that sentenced Van Oldenbarnevelt to death and would conduct a true reign of terror as a magistrate in Leiden. “First the tyranny of King Philip, now that of King Brouchoven,” wrote the great poet Vondel.

In November 1618, a synod was convened in Dort to resolve the ecclesiastical dispute. Church ministers from all parts of the Dutch Republic, along with delegates from other countries, flocked to Dordrecht. The orthodox Counter-Remonstrants easily outnumbered their opponents, and succeeded in adopting a motion condemning the Arminian position. At the end of the synod, six months later, the Canons of Dort were added to the Dutch articles of faith and the Heidelberg Catechism. Any preacher who refused to sign was dismissed. Many were banished or obliged to go into exile.

One of the refugees was Johannes Wtenbogaert, who, as court preacher of Maurits in The Hague, had fallen into disfavour since submitting the Remonstrance. After the arrest of his good friends Van Oldenbarnevelt and Grotius, he went into hiding. On 24th May 1619, eleven days after the execution of Oldenbarnevelt, he was banished and his property seized. Wtenbogaert fled to Rouen by way of Antwerp. He stayed away until after the death of Maurits in 1625. He then found a hiding place in Rotterdam until he was able to quietly move back to The Hague.

Rembrandt knew Wtenbogaert not only by reputation, but also through the latter’s nephew and godson Joannes, who came to study in Leiden in 1626. Joannes went to live on Nieuwsteeg, lodging with a former deputy headmaster of the Latin school, Hendrik Swaerdecroon, whose brother-in-law was married to a cousin of Rembrandt’s mother. Though only distant cousins, they must have felt a strong sense of kinship. Swaerdecroon had resigned his position at the school on a point of principle: he refused to sign the new oath of office that was prescribed by the Synod of Dort.

On 13th April 1633, Rembrandt painted Wtenbogaert’s portrait. We know the exact date, because of an entry in the Remonstrant preacher’s diary: “April 13, painted by Rembrandt for Abraham Anthonissen.” Abraham Anthonisz Recht was a wealthy, assertive Remonstrant who had commissioned the artist to produce a portrait of his spiritual leader.

Rembrandt clearly had warm feelings for Wtenbogaert, judging by the unpretentious, amiable way he has depicted him. The portrait radiates the message: “This is a fine human being.” He is shown hand on heart, skullcap on his head, with a folio propped up on a stand on the table, probably one in which the preacher had entrusted his reflections to paper.

Two years later, Rembrandt produced another portrait of Wtenbogaert, this time an etching. Beneath the print, which shows the preacher in a study crammed full of papers and vellum, his right hand placed defiantly on his side, Hugo Grotius inscribed some lines of verse in Latin, with the following message:

By the pious and the army, of this man much was spoken,

But what he preached, Dort’s ministers abhorred.

He was most sorely tried by time but never broken:

Behold, The Hague, Wtenbogaert to his home is now restored.

Nowhere in Holland, after the Synod of Dort, were the Remonstrants persecuted for so long and with such ferocity as in Leiden. In Maurits’s clean sweep of the city government, the old sheriff, although a life appointee, was dismissed and replaced by a man who embarked on a fanatical, implacable rout of the Remonstrants: Willem de Bondt.

The new sheriff came from a family of good standing and had excellent ties with the local élite. He was the son of Gerardus Bontius, the first professor of medicine to be appointed to the University of Leiden, who also served two terms as vice-chancellor.

Johannes Wtenbogaert, 1633.

Willem de Bondt’s ascent to a professorship in law led to membership of the city’s advisory council or vroedschap and thence to his appointment as sheriff. It placed him in a pivotal role. He was head of police, patron of the university, and in charge of administering the law. In accepting this position, financial considerations would have come into play: De Bondt received a sum of money for each arrest, and when a convict’s property was seized he was entitled to a share of the proceeds.

Petrus Scriverius was convicted of writing a caption to a portrait print of the imprisoned Remonstrant leader Hoogerbeets. Sheriff De Bondt imposed a fine of 200 guilders, but Scriverius refused to pay. When the bailiff came to collect the money, Scriverius took the man into his study and showed him his library, saying: “These books taught me how to tell justice from injustice: these caused the offence, so let the fine too be taken from them.”

De Bondt himself did not lead a blameless life. On the contrary, he was accused of corruption, intemperate drinking and neglect of his official duties. He was unfussy about marital fidelity—in the Leiden bars he haunted, he would bellow to all and sundry that his wife Maria was happy to have the organist of the Hooglandse Kerk play upon her—and lax in his attendance at Sunday services.

On New Year’s Day 1634, De Bondt and his officers attacked a group of Remonstrants. Two weeks later, his small dog Tyter died under suspicious circumstances. Man and dog (Dutch hond) had been inseparable companions. Vondel wrote a few lines of verse that translate roughly as:

Tyter was his master’s joy.

Where’er he went, where’er was found

Tyter was never without his Bondt.

Suspecting foul play, the sheriff enlisted the help of the well-known professor Adriaen van Valckenburgh to perform an autopsy on the dog. Had Tyter been strangled or poisoned? De Bondt then gave his dead companion a ceremonial funeral. The lifeless body was carried solemnly to its grave, followed by an odd procession of professors, dignitaries, the little dogs Vorst and Spier and the dog belonging to Professor Schrevel—all draped in mourning garb. At the funeral feast that was hosted after the ceremony, the local Calvinist élite came to pay their respects, including the feared magistrate Van Brouchoven.

The interment of Tyter provoked a flurry of scorn and mockery throughout Holland. Vondel penned his satirical poem, “Funeral of the Hond of Sheriff Bont,” and Jan Miense Molenaer produced two paintings depicting Tyter’s sickbed and his funeral. The Arminians were outraged: a sheriff who treated them like dogs, but buried his dog as if it were his own child. Rembrandt had already moved to Amsterdam by the time of the canine committal, but even there the events in Leiden were the talk of the town.

Notwithstanding the fun people had with their jests about the “renowned hound”, there was nothing funny about the religious persecution in Leiden. After 1574, when Catholics were prohibited from celebrating Mass in public and their churches and religious houses were confiscated, a similar ban followed for Remonstrants in 1619: henceforth, they had to congregate in secret. Each time they met they risked arrest, a fine, a beating or banishment from the city. When Remonstrants went to listen to a preacher’s sermon in a field or in the nearby village of Warmond, Calvinist ruffians would ambush them on their way home, pelting stones at them from the embankments.

On 21st April 1619, the Knotters, a wealthy family of cloth merchants who had paintings by Lucas van Leyden and his teacher Cornelis Engebrechtsz hanging on the wall, offered the Remonstrants some space in a back room of one of their houses on Rapenburg—present-day numbers 45–47, once part of the Roma convent. During their service, the rabble lobbed stones at the windows, smashing them. The preacher was pelted with stones and filth as he fled. When the mob caught up with him, they tossed him into the ditch behind the house. The contents of the house were strewn across the cobblestones of Rapenburg.

Claes Jansz Visscher II, Beheading of Arminians in Leiden and Rotterdam (detail), 1623.

The magistrate did not merely turn a blind eye to this terror, but condoned it quite openly. Stone-throwers and plunderers were acquitted and Remonstrant gatherings prohibited on pain of a 200-guilder fine. The Remonstrants themselves were blamed for the events, like Paul in Thessalonica. In the Acts of the Apostles (17: 5–8), the Apostle himself is accused of causing a riot, rather than the rioters, whose rampage is described in the text: “But the Jews which believed not, moved with envy, took unto them certain lewd fellows of the baser sort, and gathered a company, and set all the city on an uproar, and assaulted the house of Jason, and sought to bring them out to the people.”

Three men of Leiden met a far worse fate. These were the “Arminian traitors” who had conspired with the sons of Johan van Oldenbarnevelt in a plot against the life of Prince Maurits. On 21st June 1623, Jan Pietersz, rope-maker, Gerrit Kornelisz, tailor, and Samuel de Plecker, saai cloth-worker, were beheaded at the square known as Schoonverdriet near Gravensteen. The rope-maker went first. He shook hands with the preacher who had prayed for him before the executioner pulled a red cap down over his eyes, told him to kneel down “and chopped off his head, in a slightly sideways direction”.

Did Rembrandt go and watch the execution? The beheading of Leiden’s Remonstrants took place just a stone’s throw from the studio of the first master to whom he was apprenticed.