ON 27TH APRIL 1630, REMBRANDT’S FATHER HARMEN WAS BURIED, having died at the age of sixty-three. His son would reach the same age. Although the cause of death is unknown, the miller had evidently lived his last years in a frail state, given that poor health had caused him to step down as neighbourhood master or buurtheer six years before.

Harmen was buried in the family grave in the Pieterskerk. It has always been assumed that the Van Rijn family grave was somewhere in the “middle church”, the central part of the Pieterskerk nave, but it was never known exactly where. Collating the church’s burial book for 1610 with the personal archives of a Leiden mathematician and amateur historian, Robert Oomes, which include a seventeenth-century floor plan with numbered graves, we can infer the precise location: right under the pulpit.

In the time that the windmills still stood outside Leiden, and millers lived beyond the formal city limits, Rembrandt’s ancestors attended Mass at the Church of Our Lady every Sunday. They belonged to the confraternity and sorority of St Victor, patron saint of millers, who died as a martyr, according to legend, by being cast into the water with a millstone around his neck. The millers had their own altar in the church, above which hung a triptych depicting the drowning Victor and a tabernacle with gold and silver chalices and candlesticks.

All this changed after 1573, with the death of Gerrit Roelofsz, Rembrandt’s grandfather, and the blaze that destroyed his windmill. His widow Lijsbeth remarried and went to live in Weddesteeg. She and her new husband, the miller Cornelis van Berckel, now lived within the city walls, in the parish of the Pieterskerk. Their son Harmen abandoned the Catholic Church and converted to Protestantism.

In 1610, the church wardens approved a drastic operation. Since the tombstone floor was damaged, they decided to replace broken slabs, straighten others and renumber each grave. A new grave book was started that year, and Harmen and his stepfather are both mentioned as owners. On 18th March 1611 they went to the church in this connection. The note beside number 60 in the middle church reads: “belongs to Harmen Gerritsz, miller”, while number 71 in the same section reads “belongs to Cornelis Claesz, miller”.

These two graves, as is clear from the resurfaced floor plan of the church, lay end to end: the foot end of number 60 touched the head end of 71. That was no coincidence. It was good to know that you would be lying together after death, just as families lived together in Weddesteeg.

Furthermore, the proximity offered a practical advantage. Four coffins could be stacked in each tomb. If there was no space for a new deceased, it was permissible, some ten years after a relative’s death, to flatten their coffin. But if the dead piled up too quickly, during an epidemic or following instances of child mortality, you could hack a hole in the partition between the two graves through which to push a coffin into the other space. At funerals, when the stone slab was lifted, the stench must have been unbearable.

In their grave number 60 in the middle church, Harmen and Neeltje had buried two young children not long before Rembrandt’s birth. In 1625 their daughter Machtelt succumbed to the Plague. On 21st January 1627, Grandfather Cornelis had been interred in his final resting place in mid-section number 71, one place farther to the east, his head facing towards Jerusalem.

On 27th April 1630, Harmen’s coffin was carried from Weddesteeg along Noordeinde and Rapenburg to the church, in the presence of his wife Neeltje, their sons and daughters, other relatives and in-laws. When the funeral procession reached the square outside the Pieterskerk and approached its massive open doors, the bells tolled.

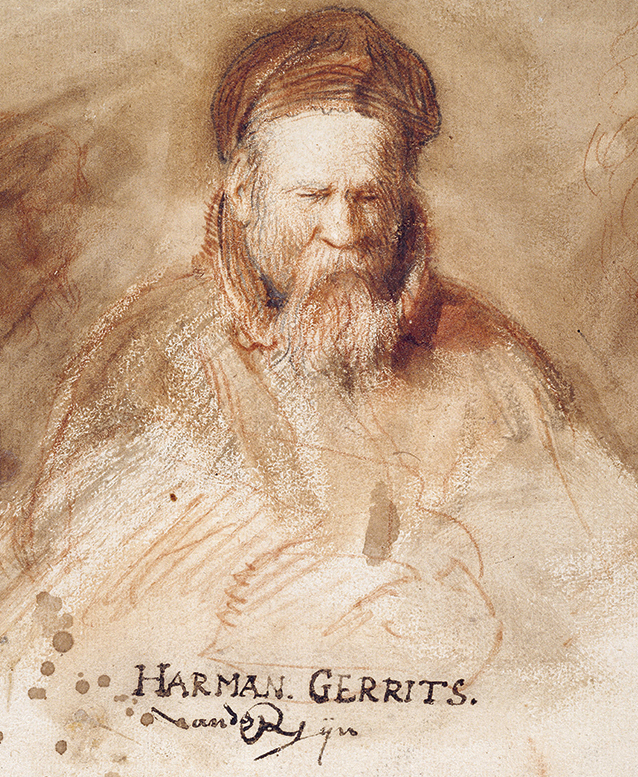

The death of his father must have been a profoundly sad and existential experience. He made a drawing of the old man in red and black chalk, with a brush and bistre. Beneath the portrait, in the middle, he added a caption, as if chiselled into a gravestone:

HARMAN. GERRITS

Van den Rhijn

Is this drawing of Rembrandt’s father, with a long grey beard, sunken features, eyes closed, a posthumous portrait? Harmen appears to be seated rather than lying down. Why, then, are his eyes shut?

It has been suggested that Harmen had gone blind, but there is no evidence for this in the testimony, notarial or neighbourhood registers. It is striking how frequently Rembrandt depicted blindness: poor Tobit, who lost his sight after a sparrow defecated in his eye; the horrific scene in which Samson’s eyes are gouged out. It must have been his greatest fear. How could it be otherwise for a painter whose everything came from the light in his eyes?

Portrait of his Father (detail), seventeenth century.

The father in The Return of the Prodigal Son from 1668, painted a year before Rembrandt’s own death, appears to be blind. Without wishing to claim that Rembrandt was depicting his own father or that he consulted his drawing of Harmen while making his painting, Rembrandt must have felt an affinity with this theme. Had he not, as the youngest son, had opportunities that his elder brothers had lacked? Had his father not always supported him, even when he was sent down from the university and decided to be a painter?

Given the use of different materials and the unusual signature, the 1630 drawing of Harmen may have been created at two different moments in time. That might mean that Rembrandt, having come upon his father in his chair warming his bones at the fireside, dashed off a quick chalk drawing of him. Then, when his father was dead, he closed his eyes—on paper—in a tender gesture.

Art historians are still debating the question of whether Rembrandt ever drew, etched or painted his father and mother. And if so, in which works we can see them.

It was not uncommon for painters working in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries to depict their relatives. Isaac Claesz van Swanenburg produced beautiful, stately portraits of his wife and close family members—and of himself. When Otto van Veen briefly returned to Leiden, he painted himself, standing in front of his panel with a paintbrush, at home on Pieterskerkhof, surrounded by his parents and siblings.

Throughout his life, Rembrandt also tried to find models in his immediate surroundings. He sometimes portrayed them “after life”, but he usually had his relatives and loved ones pose for a tronie, in which it was not necessary to produce a likeness. He immortalized Saskia in paint not only as his wife, but also as Flora. He depicted his last wife, Hendrickje Stoffels, asleep, with a few perfect strokes of his brush—perhaps the most beautiful drawing in the world—and bathing as the pregnant nymph Callisto.

Rembrandt’s Mother Seated at the Table, 1629–33.

Sheet of studies with three heads of an old man, 1628–32.

Why would the young Rembrandt not have asked his father and mother briefly to sit for him? They would not have needed to go anywhere. Even during his lifetime, the assumption was made that he did ask them. In 1644, a painting was recorded in a Leiden inventory, of the property of one Sybout van Caerdecamp, that depicted “a tronie of an old man, being the portrait of Mr Rembrandt’s father”.

And the 1679 inventory of the shop on Kalverstraat in Amsterdam run by the art dealer Clement de Jonghe includes two etching plates entitled “Rembrandt’s father” and “Rembrandt’s mother”. De Jonghe knew the painter very well, and based his assertion on information gained at first hand.

The etching described as a portrait of “Rembrandt’s mother” depicts an old woman who turns up with striking frequency in the master’s early work. The woman has a head like a wrinkled apple and a somewhat pinched, pointed nose.

In the etching that was sold in Clement de Jonghe’s shop, this old woman holds her blue-veined hand on her heart. She features in quite a number of etchings. In the best-known one, she sits at the table, hands folded in her lap, a black veil over her head. Is she in mourning? That etching was made in 1631, the year after father Harmen’s death.

The old woman features, for instance, in the background of Suffer Little Children to Come unto Me, and as Anna, with the little kid under her arm, in Tobit and Anna with the Kid. In 1631 Rembrandt painted her again. She is wrapped in a dark cloak and a veil woven with gold thread. Engrossed in a book, she leans slightly forward and gropes her way through the letters—we cannot read them, but they appear to be Hebrew—with the fingers of her wrinkled and time-gouged hand.

Is this the prophetess Anna? In St Luke’s Gospel we read that she was a widow of about eighty-four years of age. The ancient woman regarded Christ as the Messiah after she had seen him as a baby in the temple. Anna was “the personification of Faith”.

Gary Schwartz does not think that Rembrandt’s mother posed for this Anna. He compared the old woman to the portrait of Aeltje Pietersdr Uylenburgh, an aunt of Saskia’s, who was only two years younger than Rembrandt’s mother when he depicted her and still had fresh apple cheeks. “The old woman is at least ten years older than Neeltje’s sixty-three or sixty-four years in 1631.”

Does not one person age far more quickly than another? Can time not leave its merciless imprint on a face? Or did Rembrandt make his model older than she was? It is impossible to prove. It is a question of what you choose to believe.

What is certain is that the portrayal of decay held a certain fascination for Rembrandt. He regarded tronies of old men and women as more “painterly” than smooth young faces on which life had not yet left its traces. He was energized by the furrows in the faces of elderly men and women.

Old Woman Reading, Probably the Prophetess Anna, 1631.

Many of the tronies and history paintings that Rembrandt made have a melancholy air about them. In 1631 he depicted the grieving prophet Jeremiah. A painting as a lamentation: the prophet rests his head on his left hand, eyes cast down. The light catches the lines of anguish in his forehead. Behind Jeremiah, in the distance, Jerusalem is ablaze.

Was Rembrandt in the throes of melancholy? Leiden was not being consumed by flames, but after his father’s death he must have felt that there was little left to keep him there. That he was now truly a prodigal son.

Times were bad, the economy was stagnating. Many painters went in search of other places to market their talents. Jan Davidsz de Heem left for Haarlem. Jan van Goyen moved to The Hague. Prices for paintings were low in Leiden, since there was still no St Luke’s Guild to protect its members.

Rembrandt’s work was expensive. The fee he received for his paintings at the court in The Hague was far more than anyone in Leiden could afford to pay. He was never granted a single official commission by the Calvinist government of his native city—not only because the city’s coffers were almost empty, but also, perhaps, because of his ties with leading Remonstrants. In inventories of people’s property drawn up in Leiden in that era we scarcely come across a single one of his paintings, while works by Jan Lievens are found in abundance.

Yet even Lievens left Leiden, moving in 1631 to London. According to Orlers, he wanted to learn the customs and traditions of a different country. Lievens may himself have told his old neighbour from across the road that he “instantly became famous for his works of art” among the élite in London, where King Charles I and the Prince of Wales held their court.

Did Lievens spread his wings and soar, or skulk off with his tail between his legs? For years, Rembrandt had followed him when choosing subjects, developing new styles and techniques. More recently, however, they had been locked in ever fiercer rivalry—depicting the raising of Lazarus, making their historicizing portraits of the Winter King’s young sons, in tronies and etchings—and in these contests, Rembrandt had surpassed him.

It is unclear how Lievens reacted to this. Was he envious? According to Huygens, Lievens had “too much self-assurance”: “any criticism was either roundly rebuffed, or, if he conceded its veracity, borne ill”. That cannot have helped.

Wherever Lievens went, he adapted his style to the prevailing fashion. In London that meant emulating Anthony van Dyck, the court painter of Charles I. After three years in London he moved to Antwerp, where he produced fashionable genre paintings and got married. Ten years later he finally settled in Amsterdam.

From 1644 onward, he and Rembrandt were once more living in the same city, but we cannot be sure whether the old friends renewed their acquaintance. It cannot be ruled out: the inventory of Rembrandt’s property drawn up in 1656 contains a great many works by Lievens: the list includes a remarkable nine paintings, a mix of landscapes and figurative pieces, and a folder containing etchings and drawings. Did he keep them out of a sense of nostalgia? It seems likelier that Rembrandt bought and sold Lievens’s work, just as he traded work by Brouwer, Porcellis and Hercules Seghers.

The final piece of evidence of creative rivalry between the two friends is the adaptation of an etching. Rembrandt printed the contours of a number of Lievens’s tronies on an etching plate and proceeded to freely elaborate them. In the etching plate of the tronie of an Oriental figure whom he had endowed with a richly decorated turban, he scribbled: “Rembrandt geretuck [retouched] 1635”.

Irretrievably improved by Rembrandt.

On 20th June 1631, Rembrandt visited the notary Geerloff Jellisz Selden in Amsterdam to lend the art dealer Hendrick Uylenburgh “the sum of ten hundred guilders”. A thousand guilders. This indicates that Rembrandt was a man of means. The terms applicable to the loan to Uylenburgh were recorded by the notary—five per cent interest and repayment within five years—but the transaction itself meant in fact that Rembrandt was buying a share in the art dealer’s business. Uylenburgh frequently borrowed money with which to buy paintings that he then sold at a profit. He was a successful businessman with an impressive clientèle.

Uylenburgh was the son of a Frisian painter who had fled to Poland because he was a Mennonite. The Mennonites were radical Protestants who repudiated all violence and who were persecuted in the Netherlands. They found a safe haven in Poland. Hendrick’s father became a successful painter at the court in Kraków and trained his son in the same profession. Hendrick mediated in art purchases for the Polish king.

In the 1620s, Hendrick dared to return to Amsterdam. In 1625 he purchased a building on Breestraat—the house right next to the locks—where he set up his studio and gallery. That was the very year in which Rembrandt was studying under Pieter Lastman, in the selfsame street. He may have met Uylenburgh in that early period. The talent of the nineteen-year-old apprentice would not have escaped the art dealer’s notice.

Uylenburgh was in Leiden in March 1628 to prevent the sale of some of the paintings from his brother’s estate in Leiden. A month later, a man from Leiden ordered several paintings from him. Was the art dealer visiting Rembrandt’s studio at the time? It is possible that this was the point at which Uylenburgh started mediating in sales of Rembrandt’s work.

The Third Oriental Head, after Jan Lievens, 1635.

Marten Soolmans (1613–41), 1634.

Oopjen Coppit (1611–89), 1634.

In his accounts, the wealthy Remonstrant Amsterdam patrician Joan Huydecoper noted down that he had purchased a tronie from “warmbrant” for twenty-eight guilders on 15th June 1628. (He then deleted his misspelling and wrote “rembrant” instead.) Huydecoper lived diagonally opposite Uylenburgh in Breestraat. What could be more likely than that the art dealer had mediated in the sale?

In the summer of 1631, the painter and the art dealer agreed to conclude a closer business relationship. Uylenburgh would procure commissions from wealthy burghers for individual and group portrait paintings, and Rembrandt would paint them.

From then on, Rembrandt was less and less often to be found in Leiden. He made frequent journeys to Amsterdam by ferry boat. After 1632 he was able to travel from Haarlem in the comfortable barge that navigated straight canals to the capital. The service had become a good deal faster and more reliable, and he could now also use it to ship packages, letters or paintings. Goods and post would arrive the same day. The transport of a chest would cost six to eight stivers, depending on its size.

When he was working on an Amsterdam commission, he would lodge with Uylenburgh and his family. In the first two years, Isaack Jouderville often went along on these journeys as his companion and assistant. Isaack’s guardians always paid his travel expenses. Jouderville made sure that he always returned to Leiden, since he would otherwise forfeit his status as a burgher of the city and be required to pay ten per cent in taxes on his property.

Gerrit Dou initially remained behind to work in Rembrandt’s studio, but started up for himself in 1632 on Galgewater, where he achieved miraculous effects in the north light of his dustless attic with a brush composed of two or three tail-hairs of a marten. With their meticulously rendered details, his little paintings suggested depth but were as smooth as a mirror.

It seems likely that the first portrait that Rembrandt produced in Uylenburgh’s studio was that of Nicolaes Ruts in the autumn of 1631. Ruts was the son of Mennonite immigrants from Flanders who later became a Calvinist. He traded with Russia and Rembrandt therefore dressed him in a superb fur cloak and a fur hat. In January 1632, Rembrandt made a portrait of Marten Looten, who had been raised Calvinist but had converted in the opposite direction, becoming a Mennonite, bringing him into contact with Uylenburgh.

Looten had grown up in Leiden, where his parents worked in the cloth trade. He had moved to Amsterdam as early as 1615, so Rembrandt would not have known him. But there were others whom he knew from his Leiden days. They may have included Marten Soolmans, for instance, whose portrait Rembrandt painted in 1634, on the occasion of his marriage to Oopjen Coppit.

Rembrandt painted Marten and Oopjen in two life-sized, full-length pendants—as princely rulers. Their garments were no less lavish than those of Princess Amalia, the wife of Frederik Hendrik, whose portrait Rembrandt painted in 1633. Oopjen wears a dress of napped black satin with a brilliant lace collar, while Marten sports a ribbed silk suit, a black hat, an equally magnificent collar, silver silk garters around his legs and the largest rosettes that had ever graced a pair of shoes. “A symphony in black and white” was Theophile Thoré’s apt description of the companion pieces.

Marten’s father, Jan Soolmans, was an Antwerp merchant who traded in Spanish goods and had taken refuge in Amsterdam. He ran a sugar refinery on Keizersgracht. Marten’s mother, Wilhelmina Salen, was his second wife. Soolmans senior was fabulously rich, and an extremely unpleasant man. Church council records for 1624 document the “great turmoil in his relations with his wife”, noting that he had “beaten her and also injured his daughter”.

His father died in 1625, when Marten was aged thirteen. Three years later, the young man started studying law in Leiden and took lodgings on Rapenburg. He probably lived at number 55, part of the former Roma convent, the home of the Remonstrant family the Knotters. That was close to Rembrandt’s own house. The painter and the law student must have met at De Drie Haringen, on the corner of Noordeinde and Rapenburg. That was the inn that Isaack Jouderville’s father, Rembrandt’s pupil, had run for almost twenty years, albeit under the name of ’t Schilt van Vrankrijk. When the old Jouderville died in 1629 and his son Isaack stayed on living above the business, the inn was given back its old name and rented out to one Dionys Dammiansz.

This innkeeper crops up in a book of testimony records in Leiden’s city archives. He was the victim of a gruesome attempt on his life. One summer’s day in 1630, he had been attacked by a publican and his drunken wife outside the west city wall, on Rijndijk near the Valkenburg ferry. The publican set about the innkeeper with an axe and his wife beat him with a club, causing “injuries to the head”. Blood spurted in all directions.

Marten Soolmans and his fellow student Johannes van der Meijden—son of the burgomaster of Rotterdam—witnessed the attack. The latter went to the innkeeper’s assistance and managed to overpower the man with the axe. Beneath the witness statement, drawn up in the presence of the notary Pieter Oosterlingh, the signatures of the two law students are still clearly legible: Johannes van der Meijden and “Martinus Soolmans”.

Four years later, the painter signed his portrait of Soolmans, on the left beside the silver silk garter around his leg: “Rembrandt f… 1643” (the “f” stands for fecit).

There is another place in the archives where Rembrandt and Soolmans almost touch. On 24th March 1631, the notary Karel Outerman drafted a document for Marten’s mother Wilhelmina, who had gone to live with her son on Rapenburg, to arrange the sale of one house in Amsterdam and the management of another. That same day, the same notary, along with his colleague Dirc Jansz van Vesanevelt, drew up a separate document for a tontine.

A tontine was a collective annuity insurance. A hundred people would deposit a set amount. The deed does not specify the precise amount, but it must have been a large sum—some 100 guilders. A year later, a check would be performed to see which of the participants were still alive, after which the total would be divided among the survivors. The tontine was drawn up at the request of Gilles Thymansz van Vliet, “corn merchant within this city”, the father of the etcher Jan Gillisz van Vliet. The second person on the list is “Master Rembrandt Harmenszoon, painter.”

This document shows us at a glance the kind of circles that Rembrandt—who was evidently known as a “Master”—frequented in Leiden. Aside from a single maidservant, the list consists largely of young people from affluent Remonstrant families, who were in the ascendancy in seventeenth-century Leiden.

Let us look at a few of the other names on the tontine list: Silvester and Cornelis van Swanenburg, the son and brother of Rembrandt’s first teacher; Caspar Barlaeus, who had been dismissed from the university after Prince Maurits had changed the composition of the executive, had lodged with the Viet family and was appointed that year to a chair in philosophy at the newly founded Athenaeum Illustre in Amsterdam; the Mennonite preacher Jan le Pla, who came from a wealthy family and owned several buildings on Breestraat, at least one of which had a painting by Rembrandt hanging on the wall; Yeffgen Adriaensz van de Werff, a descendant of one of Leiden’s burgomasters during the siege; Pieter Pauw, son of the professor and anatomist who taught the first classes in anatomy; and Lijsbeth Wijbrantsdr, the mother of the painter Jan Steen.

The tontine produced something else rather wonderful. The notaries undertook in the deed to “see or speak to each of the 100 people” on the list one year later. And it is because of this that we can meet Rembrandt in the flesh, on 26th July 1632.

That day, the notary Jacob van Zwieten was despatched to the house of Hendrick Uylenburgh in Amsterdam to check if the painter was still alive. Van Zwieten knocked on the door at the gallery in Breestraat next to the locks at St Anthoniesluis. When one of Uylenburgh’s young daughters appeared, the notary asked her whether “Mr Rembrandt Harmensz van Rijn, the painter [who was lodging at that address] was at home and available”.

The little girl nodded and went to fetch him. The painter appeared in the front part of the house, where Van Zwieten asked him formally if he was the painter.

“Yes,” said he.

The notary asked if he was “hale and hearty”.

Rembrandt replied: “Yes indeed. Thanks be to God, I am in good spirits and in the best of health.”

It is clear from the notarial deed that Rembrandt was lodging only temporarily with the Uylenburgh family. He had not relinquished his studio in Leiden, but was rarely to be found there. It seems likely that after the death of his eldest, unfortunate brother Gerrit, who was buried on 23rd September 1631, he rarely returned to his native city.

We assume that he immediately returned in the barge from Amsterdam when he heard that his mother had died. That he attended the burial in the Pieterskerk, when her coffin was lowered into the family grave to the accompaniment of tolling bells on 14th September 1640. But whether he also went to the funeral of his brother Adriaen in 1652 is not known for certain.

Rembrandt rarely left Amsterdam because he was deluged with work there. There was also another reason: that was where he had met his future wife, the beguiling, vibrant Saskia van Uylenburgh, Hendrick’s cousin, the youngest daughter of the wealthy burgomaster of Leeuwarden. They probably met in the spring of 1633, when Rembrandt had completed his striking portrait of Saskia’s aunt, the church minister’s wife Aeltje van Uylenburgh. The old lady makes a remarkably alert impression, with soft facial features and a twinkle in her eye. Saskia must have been struck by the portrait of her aunt and by the young painter who had made it.

On 9th June 1633, three days after they had announced their intention to marry—in what was seen as a binding vow to God—Rembrandt made a drawing of his wife-to-be. Silverpoint on vellum. “The third day of our betrothal”, he wrote beneath it. He placed an elegant hat on Saskia’s head, gave her a rose to hold and drew a smile hovering around her face that vied with that of the Mona Lisa.

In 1631, Rembrandt had made a full-length painting of himself as an Oriental. In this portrait, the artist wears a shiny gold robe, a dark velvet cloak and a turban sporting a frivolous feather. Rembrandt’s pupils had told Arnold Houbraken that the painter was capable of spending two days “arranging a turban exactly as he wanted it”.

Self-portrait in Oriental Attire, 1631.

At the artist’s feet lies an unusual Italian hunting dog: a Lagotto Romagnolo. With its fluffy curls, warm muzzle and the white stripe over his head, it steals hearts. Because of the breed’s excellent sense of smell, these dogs were used as early as the fifteenth century to find truffles. They are keen swimmers and very adept at hunting ducks. In 1456, Andrea Mantegna painted frescoes on the wall of the bridal suite of the ducal palace in Mantua. One of them, entitled L’incontro (“The Meeting”) features a Lagotto Romagnolo at the feet of Marquis Ludovico III.

Rembrandt’s painting initially looked different. We know that because there is a copy of it without the dog—probably made by Isaack Jouderville—and because the X-ray of the original corresponds exactly to that copy. In other words, the animal must have been painted in later.

In the signature, “Rembrant f 1631”, in other words, “Rembrandt made this”, he spelt his name in full, but without the “d”. The only period in which he used this spelling was towards the end of 1632 and at the beginning of 1633. He must have added the Lagotto Romagnolo in the spring of 1633. This painting once had a pendant, only a copy of which has been preserved, depicting Saskia in Oriental costume. Rembrandt placed the dog at his feet in Amsterdam, two years after painting his self-portrait in Leiden, as a sign of faithfulness to his future wife.

Orlers wrote that “the burghers and residents [of Amsterdam] derived pleasure and delight from Rembrandt’s art” and that he was often being asked to make portraits and other pieces: “he therefore thought it right to move from Leiden to Amsterdam, and consequently departed from here”.

His breakthrough with the general public was The Anatomy Lesson of Dr Nicolaes Tulp, painted in 1632. The people of Amsterdam must have been struck dumb with astonishment when it appeared at the new weighhouse, the old St Anthony’s Gate, seat of the Surgeons’ Guild. Rembrandt had transformed a picture of death into a lively group portrait.

In the upper floor of the old St Anthony’s Gate building, at the end of the busy “artists’ street”, a specially refurbished anatomy theatre had been created. It was there that the praelector gave his second public dissection, which Rembrandt was to immortalize. On the cold morning of 31st January 1632—freezing temperatures were a prerequisite to obtain permission for the lesson, because of the body’s decomposition—the painter donned a thick cloak and ambled over to the anatomy theatre from Uylenburgh’s studio beside the lock, sketchbook under his arm. It was less than five minutes’ walk.

Rembrandt chose not to depict the weighhouse or the dissecting room in his painting. He even left out the packed crowd of spectators. The composition did not start to take shape until he contemplated the large canvas in Uylenburgh’s studio. He moved the anatomy lesson to a darkly atmospheric, almost invisible setting. An ill-defined, murky underworld. He focused all his attention on the six surgeons and Dr Tulp, allowing the light to fall on the body.

Was Rembrandt startled when he saw the dead body lying on the dissecting table?

The convict to be dissected was a man from Leiden—indeed, it was someone that he may have known.

From the anatomy book, which has been preserved in the archives of the Surgeons’ Guild, we know his name: Adriaen Adriaensz, known as “Ariskindt” (“child of Aris”) or simply “Het Kindt” (“the child”). He was born as the son of a maker of baking pots from Leiden. In a book of judicial sentences dating from 1624, his age is recorded: “19 years of age”. He was only a year older than Rembrandt.

Ariskindt had been “sentenced to death by hanging for his wantonness” the day before in connection with a robbery at the Herensluis. In stealing a cloak, he had attacked his victim so savagely that he would have killed him if the nightwatchman had not rushed to help and beaten the thief about the head with his pike.

Ariskindt was sentenced to death not only on account of this violent robbery, but above all because of his long and dreadful criminal record. During his interrogation, he was hoisted into the air with 200-pound weights suspended from his legs and left dangling in this way until he finally confessed his crimes: an endless list of thefts, burglaries and acts of violence.

The boy grew up in Leiden and ran wild from an early age. Ariskindt was not a clever thief and did not manage to conceal his crimes. He bought a chisel for ten stivers in Coornbrugsteeg to force windows. He was caught with his hand in the coat of a local gentleman. One night, a man found him in the cellar of his house, where he had broken in and lit a candle to look around.

In the book of judicial sentences, Sheriff De Bondt wrote in exasperated resignation on 16th January 1626 that Ariskindt had been arrested nine times, and four or five times he had been released “because of his youth and in hope that he might mend his ways”. Might that have lent extra significance to his other nickname, “Het Kindt”? That he was incorrigible from earliest childhood and committed his first crimes when still young?

Rembrandt may have witnessed the event in 1625 in which an executioner tied the boy to a post on the square near Gravensteen and “flogged him vigorously with the birch”, after which he was ordered not to show his face in Holland for twelve years.

Forgiveness or punishment: nothing helped. A year later, the miscreant was arrested once again. This time he was tied to a post in the field at Schoonverdriet with a “rope around his neck” and not just flogged but also branded with “the city’s branding iron”.

The keys of Leiden were burned into the young convict’s skin. Rembrandt did not paint them.