eading out loud, reading silently, being able to carry in the mind intimate libraries of remembered words, are astounding abilities that we acquire by uncertain methods. And yet, before these abilities can be acquired, a reader needs to learn the basic craft of recognizing the common signs by which a society has chosen to communicate: in other words, a reader must learn to read. Claude Lévi-Strauss tells how, when he was travelling among the Nambikwara Indians of Brazil, his hosts, seeing him write, took his pencil and paper and drew squiggly lines in imitation of his letters and demanded that he “read” what they had written. The Nambikwara expected their scribbles to be as immediately significant to Lévi-Strauss as those he drew himself.1 For Lévi-Strauss, taught to read in a European school, the notion that a system of communication should be immediately comprehensible to any other person seemed absurd. The methods by which we learn to read not only embody the conventions of our particular society regarding literacy — the channelling of information, the hierarchies of knowledge and power — they also determine and limit the ways in which our ability to read is put to use.

eading out loud, reading silently, being able to carry in the mind intimate libraries of remembered words, are astounding abilities that we acquire by uncertain methods. And yet, before these abilities can be acquired, a reader needs to learn the basic craft of recognizing the common signs by which a society has chosen to communicate: in other words, a reader must learn to read. Claude Lévi-Strauss tells how, when he was travelling among the Nambikwara Indians of Brazil, his hosts, seeing him write, took his pencil and paper and drew squiggly lines in imitation of his letters and demanded that he “read” what they had written. The Nambikwara expected their scribbles to be as immediately significant to Lévi-Strauss as those he drew himself.1 For Lévi-Strauss, taught to read in a European school, the notion that a system of communication should be immediately comprehensible to any other person seemed absurd. The methods by which we learn to read not only embody the conventions of our particular society regarding literacy — the channelling of information, the hierarchies of knowledge and power — they also determine and limit the ways in which our ability to read is put to use.

I lived for a year in Sélestat, a small French town twenty miles south of Strasbourg, in the middle of the Alsatian plain between the Rhine River and the Vosges Mountains. There, in the small municipal library, are two large handwritten notebooks. One is 300 pages long, the other 480; in both the paper has yellowed over the centuries, but the writing, in different colours of ink, is still surprisingly clear. Later in life, their owners had the notebooks bound in order to preserve them better, but when they were in use they were little more than bundles of folded pages, probably bought at a bookseller’s stall in one of the local markets. Open to the gaze of the library’s visitors, they are — a typed card explains — the notebooks of two of the students who attended the Latin school of Sélestat in the last years of the fifteenth century, from 1477 to 1501: Guillaume Gisenheim, of whose life nothing is known except what his schoolboy’s notebook tells us, and Beatus Rhenanus, who was to become a leading figure in the humanist movement and the editor of many of the works of Erasmus.

In Buenos Aires, in the first few grades, we too had “reading” notebooks, laboriously handwritten and painstakingly illustrated with coloured crayons. Our desks and benches were fixed to each other by cast-iron brackets and set in long rows of two, leading (the symbol of power did not escape us) up to the teacher’s desk, high on a wooden platform, behind which loomed the blackboard. Each desk was pierced to hold a white porcelain inkpot into which we plunged the metal nibs of our pens; we were not allowed to use fountain-pens until grade three. Centuries from now, if some scrupulous librarian were to exhibit those notebooks as precious objects in glass cases, what would a visitor discover? From the patriotic texts copied out in tidy paragraphs, the visitor might deduce that in our education the rhetoric of politics superseded the niceties of literature; from our illustrations, that we learned to transform these texts into slogans (“The Malvinas Belong To Argentina” became two hands linked around a pair of ragged islands; “Our Flag Is The Emblem Of Our Homeland”, three strips of colour blowing in the wind). From the identical glosses the visitor might learn that we were taught to read not for pleasure or for knowledge but merely for instruction. In a country where inflation was to attain a monthly 200 per cent, this was the only way to read the fable of the grasshopper and the ant.

In Sélestat there were several different schools. A Latin school had existed since the fourteenth century, lodged on church property and maintained by both the municipal magistrate and the parish. The original school, the one attended by Gisenheim and Rhenanus, had occupied a house on the Marché-Vert, in front of the eleventh-century church of St. Foy. In 1530 the school had become more prestigious and had moved to a larger building across from the thirteenth-century church of St. George, a two-storey house that carried on its façade an inspiring fresco depicting the nine muses sporting in the sacred fountain of Hippocrene, on Mount Helicon.2 With the transfer of the school, the name of the street changed from Lottengasse to Babilgasse, in reference to the babbling (in Alsatian dialect, bablen, “to babble”) of the students. I lived only a couple of blocks away.

From the beginnings of the fourteenth century, there exist full records of two German schools in Sélestat; then, in 1686, the first French school was opened, thirteen years after Louis XIV took possession of the town. These schools taught reading, writing, singing and a little arithmetic in the vernacular, and were open to all. An admission contract for one of the German schools, around the year 1500, notes that the teacher would instruct “members of the guilds and others from the age of twelve on, as well as those children unable to attend the Latin school, boys as well as girls.”3 Unlike those attending the German schools, students were admitted to the Latin school at the age of six, and remained there until they were ready for university at thirteen or fourteen. A few became assistants to the teacher and stayed on until the age of twenty.

Though Latin continued to be the language of bureaucracy, ecclesiastical affairs and scholarship in most of Europe until well into the seventeenth century, by the early sixteenth century the vernacular languages were gaining ground. In 1521, Martin Luther began publication of his German Bible; in 1526, William Tyndale brought out his English translation of the Bible in Cologne and Worms, having been forced to leave England under threat of death; in 1530, in both Sweden and Denmark, a government decree prescribed that the Bible was to be read in church in the vernacular. In Rhenanus’s days, however, the prestige and official use of Latin continued not only in the Catholic Church, where priests were required to conduct services in Latin, but also in universities such as the Sorbonne, which Rhenanus wished to attend. Latin schools were therefore still in great demand.

Schools, Latin and otherwise, provided a certain degree of order in the chaotic existence of students in the late Middle Ages. Because scholarship was seen as the seat of a “third power” positioned between the Church and the State, students were granted a number of official privileges from the twelfth century on. In 1158, the German Holy Roman emperor Frederick Barbarossa exempted them from the jurisdiction of secular authorities except in serious criminal cases, and guaranteed them safe conduct when travelling. A privilege accorded by King Philippe Auguste of France in 1200 forbade the Provost of Paris to imprison them under any excuse. And from Henry III onwards, each English monarch guaranteed secular immunity to the students at Oxford.4

To attend school, students had to pay tax-fees, and they were taxed according to their bursa, a unit based on their weekly bed and board. If they were unable to pay, they had to swear that they were “without means of support” and sometimes they were granted fellowships assured by subventions. In the fifteenth century, poor students accounted for 18 per cent of the student body in Paris, 25 per cent in Vienna and 19 per cent in Leipzig.5 Privileged but penniless, anxious to preserve their rights but uncertain about how to make a living, thousands of students roamed the land, living off alms and larceny. A few survived by pretending to be fortune-tellers or magicians, selling miraculous trinkets, announcing eclipses or catastrophes, conjuring up spirits, predicting the future, teaching prayers to rescue souls from purgatory, giving out recipes to guard crops against hail and cattle against disease. Some claimed to be descendants of the Druids and boasted that they had entered the Mountain of Venus, where they had been initiated into the secret arts; as a sign of this, they wore capes of yellow netting over their shoulders. Many went from town to town following an older cleric whom they served and from whom they sought instruction; the teacher was known as a bacchante (not from “Bacchus” but from the verb bacchari, “to roam”), and his disciples were called Schützen (protectors) in German or bejaunes (dunces) in French. Only those who were determined to become clerics or to enter some form of civil service would seek the means to leave the road and enter a learning establishment6 like the Latin school in Sélestat.

The students who attended the Latin school in Sélestat came from different parts of Alsace and Lorraine, and even farther, from Switzerland. Those who belonged to rich bourgeois or noble families (as was the case with Beatus Rhenanus) could choose to be lodged in the boarding-house run by the rector and his wife, or to stay as paying guests at the house of their private tutor, or even at one of the local inns.7 But those who had sworn that they were too poor to pay their fees had great difficulties in finding room and board. The Swiss Thomas Platter, who arrived at the school in 1495 at the age of eighteen “knowing nothing, unable even to read [the best-known of medieval grammar primers, the Ars de octo partibus orationis by Aelius] Donat”, and who felt, among the younger students, “like a hen among the chicks”, described in his autobiography how he and a friend had set off in search of instruction. “When we reached Strasbourg, we found many poor students there, who told us that the school was not good, but that there was an excellent school in Sélestat. We set off for Sélestat. On the way we met a nobleman who asked us, ‘Where are you going?’ When he heard that we were headed for Sélestat, he advised us against it, telling us that there were many poor students in that town and that the inhabitants were far from rich. Hearing this, my companion burst into bitter tears, crying, ‘Where can we go?’ I comforted him by saying, ‘Rest assured, if some can find the means of obtaining food in Sélestat, I’ll certainly manage to do so for both of us.’ ” They managed to stay in Sélestat for a few months, but after Pentecost “new students arrived from all parts, and I no longer was able to find food for both of us, and we left for the town of Soleure.”8

In every literate society, learning to read is something of an initiation, a ritualized passage out of a state of dependency and rudimentary communication. The child learning to read is admitted into the communal memory by way of books, and thereby becomes acquainted with a common past which he or she renews, to a greater or lesser degree, in every reading. In medieval Jewish society, for instance, the ritual of learning to read was explicitly celebrated. On the Feast of Shavuot, when Moses received the Torah from the hands of God, the boy about to be initiated was wrapped in a prayer shawl and taken by his father to the teacher. The teacher sat the boy on his lap and showed him a slate on which were written the Hebrew alphabet, a passage from the Scriptures and the words “May the Torah be your occupation.” The teacher read out every word and the child repeated it. Then the slate was covered with honey and the child licked it, thereby bodily assimilating the holy words. Also, biblical verses were written on peeled hard-boiled eggs and on honey cakes, which the child would eat after reading the verses out loud to the teacher.9

Though it is difficult to generalize over several centuries and across so many countries, in the Christian society of the late Middle Ages and the early Renaissance learning to read and write — outside the Church — was the almost exclusive privilege of the aristocracy and (after the thirteenth century) the upper bourgeoisie. Even though there were aristocrats and grands bourgeois who considered reading and writing menial tasks suitable only for poor clerics,10 most boys and quite a few girls born to these classes were taught their letters very early. The child’s nurse, if she could read, initiated the teaching, and for that reason had to be chosen with utmost care, since she was not only to provide milk but also to ensure correct speech and pronunciation.11 The great Italian humanist scholar Leon Battista Alberti, writing between 1435 and 1444, noted that “the care of very young children is women’s work, for nurses or the mother,”12 and that at the earliest possible age they should be taught the alphabet. Children learned to read phonetically by repeating letters pointed out by their nurse or mother in a hornbook or alphabet sheet. (I myself was taught this way, by my nurse reading out to me the bold-type letters from an old English picture-book; I was made to repeat the sounds again and again.) The image of the teaching mother-figure was as common in Christian iconography as the female student was rare in depictions of the classroom. There are numerous representations of Mary holding a book in front of the Child Jesus, and of Anne teaching Mary, but neither Christ nor His Mother was depicted as learning to write or actually writing; it was the notion of Christ reading the Old Testament that was considered essential to make the continuity of the Scriptures explicit.

Two fifteenth-century mothers teaching their children to read: left, the Virgin and Child; right, Saint Anne with the young Mary. (photo credit 5.1)

Quintilian, a first-century Roman lawyer from northern Spain who became the tutor of the Emperor Domitian’s grand-nephews, wrote a twelve-volume pedagogical manual, the Institutio oratoria, which was highly influential throughout the Renaissance. In it, he advised: “Some hold that boys should not be taught to read till they are seven years old, that being the earliest age at which they can derive profit from instruction and endure the strain of learning. Those however who hold that a child’s mind should not be allowed to lie fallow for a moment are wiser. Chrysippus, for instance, though he gives the nurses a three years’ reign, still holds the formation of the child’s mind on the best principles to be a part of their duties. Why, again, since children are capable of moral training, should they not be capable of literary education?”13

After the letters had been learned, male teachers would be brought in as private tutors (if the family could afford them) for the boys, while the mother busied herself with the education of the girls. Even though, by the fifteenth century, most wealthy houses had the space, quiet and equipment to provide teaching at home, most scholars recommended that boys be educated away from the family, in the company of other boys; on the other hand, medieval moralists hotly debated the benefits of education — public or private — for girls. “It is not appropriate for girls to learn to read and write unless they wish to become nuns, since they might otherwise, coming of age, write or receive amorous missives,”14 warned the nobleman Philippe de Novare, but several of his contemporaries disagreed. “Girls should learn to read in order to learn the true faith and protect themselves from the perils that menace their soul,” argued the Chevalier de la Tour Landry.15 Girls born in richer households were often sent to school to learn reading and writing, usually to prepare them for the convent. In the aristocratic households of Europe, it was possible to find women who were fully literate.

Before the mid-fifteenth century, the teaching at the Latin school of Sélestat had been rudimentary and undistinguished, following the conventional precepts of the scholastic tradition. Developed mainly in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, by philosophers for whom “thinking is a craft with meticulously fixed laws”,16 scholasticism proved a useful method for reconciling the precepts of religious faith with the arguments of human reason, resulting in a concordia discordantium or “harmony among differing opinions” which could then be used as a further point of argument. Soon, however, scholasticism became a method of preserving rather than eliciting ideas. In Islam it served to establish the official dogma; since there were no Islamic councils or synods set up for this purpose, the concordia discordantium, the opinion that survived all objections, became orthodoxy.17 In the Christian world, though varying considerably from university to university, scholasticism adamantly followed the precepts of Aristotle by way of early Christian philosophers such as the fifth-century Boethius, whose De consolatione philosophiae (which Alfred the Great translated into English) was a great favourite throughout the Middle Ages. Essentially, the scholastic method consisted in little more than training the students to consider a text according to certain pre-established, officially approved criteria which were painstakingly and painfully drilled into them. As far as the teaching of reading was concerned, the success of the method depended more on the students’ perseverance than on their intelligence. Writing in the mid-thirteenth century, the learned Spanish king Alfonso el Sabio belaboured the point: “Well and truly must the teachers show their learning to the students by reading to them books and making them understand to the best of their abilities; and once they begin to read, they must continue the teaching until they have come to the end of the books they have started; and while in health they must not send for others to read in their place, unless they are asking someone else to read in order to show him honour, and not to avoid the task of reading.”18

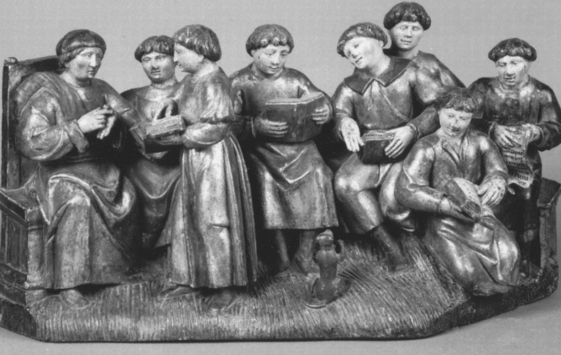

Two school scenes from the turn of the fifteenth century showing the hierarchical relationship between teachers and students: left, Aristotle and his disciples; right, an anonymous class. (photo credit 5.2)

Well into the sixteenth century, the scholastic method was prevalent in universities and in parish, monastic and cathedral schools throughout Europe. These schools, the ancestors of the Latin school of Sélestat, had begun to develop in the fourth and fifth centuries after the decline of the Roman educational system, and had flourished in the ninth, when Charlemagne ordered all cathedrals and churches to provide schools for training clerics in the arts of reading, writing, chant and calculus. In the tenth century, when the resurgence of the towns made it essential to have centres of basic learning, schools established themselves around the figure of a particularly gifted teacher on whom the school’s fame then depended.

A scene from an early sixteenth-century school in France. (photo credit 5.3)

A teacher continues his lesson beyond the grave, his craft commemorated on a mid-fourteenth-century Bolognese tomb. (photo credit 5.4)

The physical aspect of the schools did not change much from the times of Charlemagne. Classes were conducted in a large room. The teacher usually sat at an elevated lectern, or sometimes at a table, on an ordinary bench (chairs did not become common in Christian Europe until the fifteenth century). A marble sculpture from a Bolognese tomb, from the mid-fourteenth century, shows a teacher seated on a bench, a book open on the desk in front of him, looking out at his students. He is holding a page open with his left hand, while his right hand seems to be stressing a point, perhaps explaining the passage he has just read out loud. Most illustrations show the students sitting on benches, holding lined pages or wax tablets for taking notes, or standing around the teacher with open books. One signboard advertising a school in 1516 depicts two adolescent students working on a bench, hunched over their texts, while on the right a woman seated at a lectern is guiding a much younger child by pointing a finger at a page; on the left a student, probably in his early teens, stands at a lectern, reading from an open book, while the teacher behind him holds a bundle of birches to his buttocks. The birch, as much as the book, would be the teacher’s emblem for many centuries.

A signboard advertising a school, painted in 1516 by Ambrosius Holbein. (photo credit 5.5)

In the Latin school of Sélestat, students were first taught to read and write, and later learned the subjects of the trivium: grammar above all, rhetoric and dialectics. Since not all students arrived with a knowledge of their letters, reading would begin with an ABC or primer and collections of simple prayers such as the Lord’s Prayer, Hail Mary and Apostles’ Creed. After this rudimentary learning, the students were taken through several reading manuals common in most medieval schools: Donat’s Ars de octo partibus orationis, the Doctrinale puerorum by the Franciscan monk Alexandre de Villedieu and the Handbook of Logic by Peter the Spaniard. Few students were rich enough to buy books,19 and often only the teacher possessed these expensive volumes. He would copy the complicated rules of grammar onto the blackboard — usually without explaining them, since, according to scholastic pedagogy, understanding was not a requisite of knowledge. The students were then forced to learn the rules by heart. As might be expected, the results were often disappointing.20 One of the students who attended the Sélestat Latin school in the early 1450s, Jakob Wimpfeling (who was to become, like Rhenanus, one of the most noted humanists of his age), commented years later that those who had studied under the old system “could neither speak Latin nor compose a letter or a poem, nor even explain one of the prayers used at Mass.”21 Several factors made reading difficult for a novice. As we have seen, punctuation was still erratic in the fifteenth century, and upper-case letters were used inconsistently. Many words were abbreviated, sometimes by the student hastening to take notes, but often as the common manner of writing out a word — perhaps to save paper — so the reader not only had to be able to read phonetically but also had to recognize what the abbreviation stood for. Finally, spelling was not uniform; the same word could appear under several different guises.22

An illuminated miniature showing a teacher ready to punish his student, in a late fifteenth-century French translation of Aristotle’s Politics. (photo credit 5.6)

Following the scholastic method, students were taught to read through orthodox commentaries that were the equivalent of our potted lecture notes. The original texts — whether those of the Church Fathers or, to a far lesser extent, those of the ancient pagan writers — were not to be apprehended directly by the student but to be reached through a series of preordained steps. First came the lectio, a grammatical analysis in which the syntactic elements of each sentence would be identified; this would lead to the littera or literal sense of the text. Through the littera the student acquired the sensus, the meaning of the text according to different established interpretations. The process ended with an exegesis — the sententia — in which the opinions of approved commentators were discussed.23 The merit of such a reading lay not in discovering a private significance in the text but in being able to recite and compare the interpretations of acknowledged authorities, and thus becoming “a better man”. With these notions in mind, the fifteenth-century professor of rhetoric Lorenzo Guidetti summed up the purpose of teaching proper reading: “For when a good teacher undertakes to explicate any passage, the object is to train his pupils to speak eloquently and to live virtuously. If an obscure phrase crops up which serves neither of these ends but is readily explicable, then I am in favour of his explaining it. If its sense is not immediately obvious, I will not consider him negligent if he fails to explicate it. But if he insists on digging out trivia which require much time and effort to be expended in their explication, I shall call him merely pedantic.”24

In 1441, Jean de Westhus, priest of the Sélestat parish and the local magistrate, decided to appoint a graduate of Heidelberg University — Louis Dringenberg — to the post of director of the school. Inspired by the contemporary humanist scholars who were questioning the traditional instruction in Italy and The Netherlands, and whose extraordinary influence was gradually reaching France and Germany, Dringenberg introduced fundamental changes. He kept the old reading manuals of Donat and Alexandre, but made use of only certain sections of their books, which he opened for discussion in class; he explained the rules of grammar, rather than merely forcing his students to memorize them; he discarded the traditional commentaries and glosses, which he found did “not help students to acquire an elegant language”,25 and worked instead with the classic texts of the Church Fathers themselves. By largely disregarding the conventional stepping-stones of the scholastic annotators, and by allowing the class to discuss the texts being taught (while still maintaining a strict guiding hand over the discussions), Dringenberg granted his students a greater degree of reading freedom than they had ever known before. He was not afraid of what Guidetti dismissed as “trivia”. When he died in 1477, the basis for a new manner of teaching children to read had been firmly established in Sélestat.26

Dringenberg’s successor was Crato Hofman, also a graduate of Heidelberg, a twenty-seven-year-old scholar whose students remembered him as “joyfully strict and strictly joyful”,27 who was quite ready to use the cane on anyone not sufficiently dedicated to the study of letters. If Dringenberg had concentrated his efforts on acquainting his students with the Church Fathers’ texts, Hofman preferred the Roman and Greek classics.28 One of his students noted that, like Dringenberg, “Hofman abhorred the old commentaries and glosses”;29 rather than take the class through a morass of grammatical rules, he proceeded very quickly to the reading of the texts themselves, adding to them a wealth of archeological, geographical and historical anecdotes. Another student recalled that, after Hofman had guided them through the works of Ovid, Cicero, Suetonius, Valerius Maximus, Antonius Sabellicus and others, they reached the university “perfectly fluent in Latin and with a profound knowledge of grammar”.30 Although calligraphy, “the art of writing beautifully”, was never neglected, the ability to read fluently, accurately and intelligently, deftly “milking the text for every drop of sense”, was for Hofman the utmost priority.

But even in Hofman’s class, the texts were never left entirely open to the students’ chance interpretation. On the contrary, they were systematically and rigorously dissected; from the copied words a moral was extracted, as well as politeness, civility, faith and warnings against vices — every sort of social precept, in fact, from table manners to the pitfalls of the seven deadly sins. “A teacher,” wrote a contemporary of Hofman’s, “must not only teach reading and writing, but also Christian virtues and morals; he must strive to seed the child’s soul with virtue; this is important, because, as Aristotle says, a man behaves in later life according to the education he has received; all habits, especially good habits, having taken root in a man during his youth, cannot afterwards be uprooted.”31

The Sélestat notebooks of Rhenanus and Gisenheim begin with Sunday prayers and selections from the Psalms which the students would copy from the blackboard on the first day of class. These they probably already knew by heart; in copying them out mechanically — not yet knowing how to read — they would have associated the series of words with the sound of the memorized lines, as in the “global” method for teaching reading laid out two centuries later by Nicolas Adam in his A Trustworthy Method of Learning Any Language Whatsoever: “When you show a child an object, a dress for instance, has it ever occurred to you to show him separately first the frills, then the sleeves, after that the front, the pockets, the buttons, etc.? No, of course not; you show him the whole and say to him: this is a dress. That is how children learn to speak from their nurses; why not do the same when teaching them to read? Hide from them all the ABCs and all the manuals of French and Latin; entertain them with whole words which they can understand and which they will retain with far more ease and pleasure than all the printed letters and syllables.”32

In our time, the blind learn to read in a similar manner, by “feeling” the entire word — which they know already — rather than deciphering it letter by letter. Recalling her education, Helen Keller said that as soon as she had learned to spell, her teacher gave her slips of cardboard on which whole words were printed in raised letters. “I quickly learned that each printed word stood for an object, an act or a quality. I had a frame in which I could arrange the words in little sentences; but before I ever put sentences in the frame I used to make them into objects. I found the slips of paper which represented, for example, doll, is, on, bed and placed each name on its object; then I put my doll on the bed with the words is, on, bed arranged beside the doll, thus making a sentence of the words, and at the same time carrying out the idea of the sentence with the things themselves.”33 For the blind child, since words were concrete objects that could actually be touched, they could be supplanted, as language signs, by the objects they were made to represent. This, of course, was not the case for the Sélestat students, for whom the words on the page remained abstract signs.

The same notebook was used over several years, possibly for economic reasons, because of the cost of paper, but more probably because Hofman wanted his students to keep a progressive record of their lessons. Rhenanus’s handwriting shows hardly any change as he copies out texts over the years. Set in the centre of the page, leaving large margins and broad spaces between lines for later glosses and comments, his handwriting imitates the Gothic script of German fifteenth-century manuscripts, the elegant hand that Gutenberg was to copy when cutting the letters for his Bible. Strong and clear, in bright purple ink, the handwriting allowed Rhenanus to follow the text with growing ease. Decorated initials appear on several pages (they remind me of the elaborate lettering with which I used to illumine my homework in the hope of better marks). After the devotions and brief quotations from the Church Fathers — all annotated with grammatical or etymological notes in black ink in the margins and between the lines, and sometimes with critical comments probably added later in the students’ career — the notebooks progress to the study of certain classical writers.

Gliding her hands over a text in Braille, Helen Keller sits by a window, reading. (photo credit 5.7)

Hofman stressed the grammatical perfection of these texts, but from time to time he was moved to remind his students that their reading was to be not only studiously analytical but also from the heart. Because he himself had found beauty and wisdom in those ancient texts, he encouraged his students to seek, in the words set down by souls long vanished, something that spoke to them personally, in their own place and time. In 1498, for instance, when they were studying books IV, V and VI of Ovid’s Fasti, and the year after, when they copied out the opening sections of Virgil’s Bucolics and then the complete Georgics, a jotted word of praise here and there, an enthusiastic gloss added to the margin, allows us to imagine that at that precise verse Hofman stopped his students to share his admiration and delight.

The school notebook of the adolescent Beatus Rhenanus, preserved at the Humanist Library in Sélestat. (photo credit 5.8)

Looking at Gisenheim’s notes, appended to the text in both Latin and German, we can follow the analytical reading that took place in Hofman’s class. Many of the words Gisenheim wrote in the margins of his Latin copy are synonyms or translations; at times the note is a specific explanation. For instance, over the word prognatos the student has written the synonym progenitos, and then explained, in German, “those who are born from yourself”. Other notes offer the etymology of a word, and its relation to its German equivalent. A favourite author at Sélestat was Isidore of Seville, the seventh-century theologian whose Etymologies, a vast work in twenty volumes, explained and discussed the meaning and use of words. Hofman seems to have been particularly concerned with instructing his students in using words correctly, being respectful of their meaning and connotations, so that they could interpret or translate with authority. At the end of the notebooks he had the students compile an Index rerum et verborum (Index of Things and Words) listing and defining the subjects they had studied, a step which no doubt gave them a sense of the progress they were making, and tools to use in other readings done on their own. Certain passages bear Hofman’s comments on the texts. In no case are the words translated phonetically, which might lead one to suppose that, before copying down a text, Gisenheim, Rhenanus and the other students had repeated it out loud a sufficient number of times to memorize its pronunciation. Nor do the sentences in the notebooks carry stresses, so we don’t know whether Hofman demanded a certain cadence in the reading or whether this was left to chance. In poetic passages, no doubt, a standard cadence would be taught, and we can imagine Hofman reading out in a booming voice the ancient and resonant lines.

The evidence that emerges from these notebooks is that, in the mid-fifteenth century, reading, at least in a humanist school, was gradually becoming the responsibility of each individual reader. Previous authorities — translators, commentators, annotators, glossers, cataloguers, anthologists, censors, canon-makers — had established official hierarchies and ascribed intentions to the different works. Now the readers were asked to read for themselves, and sometimes to determine value and meaning on their own in light of those authorities. The change, of course, was not sudden, nor can it be fixed to a single place and date. As early as the thirteenth century, an anonymous scribe had written in the margins of a monastic chronicle, “You should make it a habit, when reading books, to attend more to the sense than to the words, to concentrate on the fruit rather than the foliage.”34 This sentiment was echoed in Hofman’s teaching. In Oxford, in Bologna, in Baghdad, even in Paris, the scholastic teaching methods were questioned and then gradually changed. This was brought on in part by the sudden availability of books soon after the invention of the printing press, but also by the fact that the somewhat simpler social structure of previous European centuries, of the Europe of Charlemagne and the later medieval world, had been economically, politically and intellectually fractured. To the new scholar — to Beatus Rhenanus, for instance — the world seemed to have lost its stability and grown in bewildering complexity. As if things weren’t bad enough, in 1543 Copernicus’s controversial treatise De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (Of the Movement of Heavenly Bodies) was published, which placed the sun at the centre of the universe — displacing Ptolemy’s Almagest, which had assured the world that the earth and humankind were at the centre of all creation.35

The passage from the scholastic method to more liberated systems of thought brought another development. Until then, the task of a scholar had been — like that of the teacher — the search for knowledge, inscribed within certain rules and canons and proven systems of learning; the responsibility of the teacher had been felt to be a public one, making texts and their different levels of meaning available to the vastest possible audience, affirming a common social history of politics, philosophy and faith. After Dringenberg, Hofman and the others, the products of those schools, the new humanists, abandoned the classroom and the public forum and, like Rhenanus, retired to the closed space of the study or library, to read and think in private. The teachers of the Latin school at Sélestat passed on orthodox precepts that implied an established “correct” and common reading but also offered students the vaster and more personal humanist perspective; the students eventually reacted by circumscribing the act of reading to their own intimate world and experience and by asserting their authority as individual readers over every text.

The high school student Franz Kafka, c. 1898. (photo credit 5.9)