he pictures of medieval Europe offered a syntax without words, to which the reader silently added a narration. In our time, deciphering the pictures of advertising, of video art, of cartoons, we too lend a story not only a voice but a vocabulary. I must have read like that at the very beginning of my reading, before my encounter with letters and their sounds. I must have constructed, out of the water-colour Peter Rabbits, the brazen Struwwelpeters, the large, bright creatures in La Hormiguita Viajera, stories that explained and justified the different scenes, linking them in a possible narrative that took every one of the depicted details into account. I didn’t know it then, but I was exercising my freedom to read almost to the limit of its possibilities: not only was the story mine to tell, but nothing forced me to repeat the same tale time after time for the same illustrations. In one version the anonymous hero was a hero, in another he was a villain, in the third he bore my name.

he pictures of medieval Europe offered a syntax without words, to which the reader silently added a narration. In our time, deciphering the pictures of advertising, of video art, of cartoons, we too lend a story not only a voice but a vocabulary. I must have read like that at the very beginning of my reading, before my encounter with letters and their sounds. I must have constructed, out of the water-colour Peter Rabbits, the brazen Struwwelpeters, the large, bright creatures in La Hormiguita Viajera, stories that explained and justified the different scenes, linking them in a possible narrative that took every one of the depicted details into account. I didn’t know it then, but I was exercising my freedom to read almost to the limit of its possibilities: not only was the story mine to tell, but nothing forced me to repeat the same tale time after time for the same illustrations. In one version the anonymous hero was a hero, in another he was a villain, in the third he bore my name.

On other occasions I relinquished all these rights. I delegated both words and voice, gave up possession — and sometimes even the choice — of the book and, except for the odd clarifying question, became nothing but hearing. I would settle down (at night, but also often during the day, since frequent bouts of asthma kept me trapped in my bed for weeks) and, propped up high against the pillows, listen to my nurse read the Grimms’ terrifying fairy-tales. Sometimes her voice put me to sleep; sometimes, on the contrary, it made me feverish with excitement, and I urged her on in order to find out, more quickly than the author had intended, what happened in the story. But most of the time I simply enjoyed the luxurious sensation of being carried away by the words, and felt, in a very physical sense, that I was actually travelling somewhere wonderfully remote, to a place that I hardly dared glimpse on the secret last page of the book. Later on, when I was nine or ten, I was told by my school principal that being read to was suitable only for small children. I believed him, and gave up the practice — partly because being read to gave me enormous pleasure, and by then I was quite ready to believe that anything that gave pleasure was somehow unwholesome. It was not until much later, when my lover and I decided to read to each other, over a summer, The Golden Legend, that the long-lost delight of being read to came back to me. I didn’t know then that the art of reading out loud had a long and itinerant history, and that over a century ago, in Spanish Cuba, it had established itself as an institution within the earthbound strictures of the Cuban economy.

Cigar-making had been one of Cuba’s main industries since the seventeenth century, but in the 1850s the economic climate changed. The saturation of the American market, rising unemployment and the cholera epidemic of 1855 convinced many workers that the creation of a union was necessary to improve their conditions. In 1857 a Mutual Aid Society of Honest Workers and Day Labourers was founded for the benefit of white cigar-makers only; a similar Mutual Aid Society was founded for free black workers in 1858. These were the first Cuban workers’ unions, and the precursors of the Cuban labour movement of the turn of the century.1

In 1865, Saturnino Martínez, cigar-maker and poet, conceived the idea of publishing a newspaper for the workers in the cigar industry, which would contain not only political features but also articles on science and literature, poems and short stories. With the support of several Cuban intellectuals, Martínez brought out the first issue of La Aurora on October 22 of that year. “Its purpose,” he announced in the first editorial, “will be to illuminate in every possible way that class of society to which it is dedicated. We will do everything to make ourselves generally accepted. If we are not successful, the blame will lie in our insufficiency, not in our lack of will.” Over the years, La Aurora published work by the major Cuban writers of the day, as well as translations of European authors such as Schiller and Chateaubriand, reviews of books and plays, and exposés of the tyranny of factory owners and of the workers’ sufferings. “Do you know,” it asked its readers on June 27, 1866, “that at the edge of La Zanja, according to what people say, there is a factory owner who puts shackles on the children he uses as apprentices?”2

But, as Martínez soon realized, illiteracy was the obvious stumbling-block to making La Aurora truly popular; in the mid-nineteenth century barely 15 per cent of the working population of Cuba could read. In order to make the paper accessible to all workers, he hit on the idea of a public reader. He approached the director of the Guanabacoa high school and suggested that the school assist readings in the working-place. Full of enthusiasm, the director met with the workers of the factory El Fígaro and, after obtaining the owner’s permission, convinced them of the usefulness of the enterprise. One of the workers was chosen as the reader, the official lector, and the others paid for his efforts out of their own pockets. On January 7, 1866, La Aurora reported, “Reading in the shops has begun for the first time among us, and the initiative belongs to the honoured workers of El Fígaro. This constitutes a giant step in the march of progress and the general advance of the workers, since in this way they will gradually become familiar with books, the source of everlasting friendship and great entertainment.”3 Among the books read were the historical compendium Battles of the Century, didactic novels such as The King of the World by the now long forgotten Fernández y González and a manual of political economy by Flórez y Estrada.4

Eventually other factories followed the example of El Fígaro. So successful were these public readings that in very little time they acquired a reputation for “being subversive”. On May 14, 1866, the Political Governor of Cuba issued the following edict:

1. It is forbidden to distract the workers of the tobacco shops, workshops and shops of all kinds with the reading of books and newspapers, or with discussions foreign to the work in which they were engaged. 2. The police shall exercise constant vigilance to enforce this decree, and put at the disposal of my authority those shop owners, representatives or managers who disobey this mandate so that they may be judged by the law according to the gravity of the case.5

In spite of the prohibition, clandestine readings still took place for a time in some form or other; however, by 1870 they had virtually disappeared. In October 1868, with the outbreak of the Ten Years War, La Aurora too came to an end. And yet the readings were not forgotten. As early as 1869 they were resurrected, on American soil, by the workers themselves.

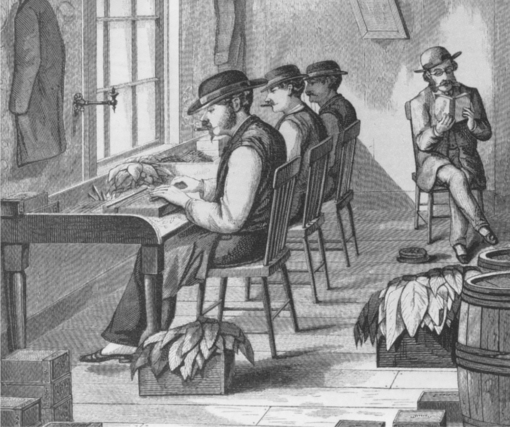

The earliest known sketch of a lector, in the Practical Magazine, New York, 1873. (photo credit 8.1)

The Ten Years War of Independence began on October 10, 1868, when a Cuban landowner, Carlos Manuel de Céspedes, and two hundred poorly armed men took over the city of Santiago and proclaimed the country’s independence from Spain. By the end of the month, after Céspedes had offered to free all slaves joining the revolution, his army had recruited twelve thousand volunteers; in April of the following year, Céspedes was elected president of the new revolutionary government. But Spain held strong. Four years later Céspedes was deposed in absentia by a Cuban tribunal, and in March 1874 he was trapped and shot by Spanish soldiers.6 In the meantime, anxious to disrupt Spain’s restrictive trade measures, the U.S. government had loudly supported the revolutionaries, and New York, New Orleans and Key West had opened their ports to thousands of fleeing Cubans. As a result, Key West was transformed in a few years from a small fishing village into a major cigar-producing community, the new Havana-cigar capital of the world.7

The workers who immigrated to the United States took with them, among other things, the institution of the lector: an illustration in the American Practical Magazine of 1873 shows one such lector, wearing glasses and a large-brimmed hat, sitting with legs crossed and a book in his hands while a row of workers (all male) in waistcoats and shirtsleeves go about their cigar-rolling with what appears to be rapt attention.

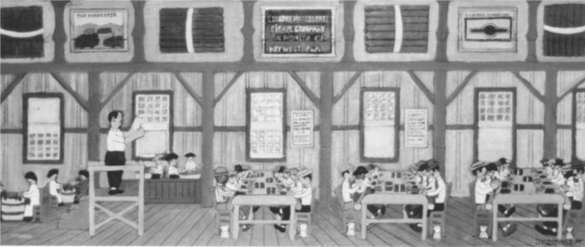

“El lector” by Mario Sánchez. (photo credit 8.2)

The material for these readings, agreed upon in advance by the workers (who, as in the days of El Fígaro, paid the lector out of their own earnings), ranged from political tracts and histories to novels and collections of poetry both modern and classical.8 They had their favourites: Alexandre Dumas’s The Count of Monte Cristo, for instance, became such a popular choice that a group of workers wrote to the author shortly before his death in 1870, asking him to lend the name of his hero to one of their cigars. Dumas consented.

According to Mario Sánchez, a Key West painter who in 1991 could still recall lectores reading to the cigar-rollers in the late twenties, the readings took place in concentrated silence, and comments or questions were not allowed until the session was over. “My father,” Sánchez reminisced, “was the reader in the Eduardo Hidalgo Gato cigar factory in the early 1900s until the 1920s. In the mornings, he read the news which he translated from the local newspapers. He read international news directly from Cuban newspapers brought daily by boat from Havana. From noon until three in the afternoons, he read from a novel. He was expected to interpret the characters by imitating their voices, like an actor.” Workers who had spent several years at the shops were able to quote from memory long passages of poetry and even prose. Sánchez mentioned one man who was able to remember the entire Meditations of Marcus Aurelius.9

Being read to, as the cigar workers found out, allowed them to overlay the mechanical, mind-numbing activity of rolling the dark scented tobacco leaves with adventures to follow, ideas to consider, reflections to make theirs. We don’t know whether, in the long workshop hours, they regretted that the rest of their body was excluded from the reading ritual; we don’t know if the fingers of those who could read longed for a page to turn, a line to follow; we don’t know if those who had never learned to read were prompted to do so.

One night a few months before his death circa 547 — some thirteen centuries before the Cuban lectors — Saint Benedict of Nursia had a vision. As he was praying by his open window, looking out into the darkness, “the whole world appeared to be gathered into one sunbeam and thus brought before his eyes”.10 In that vision, the old man must have seen, with tears in his eyes, “that secret and conjectural object whose name men have seized upon but that no man has ever beheld: the inconceivable universe”.11

An eleventh-century manuscript illumination showing Saint Benedict offering his Rules to an abbot. (photo credit 8.3)

Benedict had renounced the world at the age of fourteen and relinquished the fortunes and titles of his wealthy Roman family. Around 529 he had founded a monastery on Monte Cassino — a craggy hill towering fifteen hundred feet over an ancient pagan shrine halfway between Rome and Naples — and composed a series of rules for his friars12 in which the authority of a code of laws replaced the absolute will of the monastery’s superior. Perhaps because he sought in the Scriptures the all-encompassing vision that would be granted to him years later, or perhaps because he believed, like Sir Thomas Browne, that God offered us the world under two guises, as nature and as a book,13 Benedict decreed that reading would be an essential part of the monastery’s daily life. Article 38 of his Rule laid out the procedure:

At the meal time of the brothers, there should always be reading; no one may dare to take up the book at random and begin to read there; but he who is about to read for the whole week shall begin his duties on Sunday. And, entering upon his office after Mass and Communion, he shall ask all to pray for him, that God may avert from him the spirit of elation. And this verse shall be said in the oratory three times by all, he however beginning it: “O Lord, open Thou my lips, and my mouth shall show forth Thy praise.” And thus, having received the benediction, he shall enter upon his duties as reader. And there shall be the greatest silence at table, so that no whispering or any voice save the reader’s may be heard. And whatever is needed, in the way of food, the brethren should pass to each other in turn, so that no one need ask for anything.14

As in the Cuban factories, the book to be read was not chosen at random; but unlike the factories, where the titles were chosen by consensus, in the cloister the choice was made by the community’s authorities. For the Cuban workers, the books could become (many times did become) the intimate possession of each listener; but for the disciples of Saint Benedict, elation, personal pleasure and pride were to be avoided, since the joy of the text was to be communal, not individual. The prayer to God, asking Him to open the reader’s lips, placed the act of reading in the hands of the Almighty. For Saint Benedict the text — the Word of God — was beyond personal taste, if not beyond understanding. The text was immutable and the author (or Author) the definitive authority. Finally, the silence at table, the audience’s lack of response, was necessary not only to ensure concentration but also to preclude any semblance of private commentary on the sacred books.15

Later, in the Cistercian monasteries founded throughout Europe from the early twelfth century onwards, the Rule of Saint Benedict was used to ensure an orderly flow of monastic life in which personal agonies and desires were submitted to communal needs. Violations of the rules were punished with flagellation, and the offenders were separated from the fold, isolated from their brothers. Solitude and privacy were considered punishments; secrets were common knowledge; individual pursuits of any kind, intellectual or otherwise, were strongly discouraged; discipline was the reward of those who lived well within the community. In ordinary life, the Cistercian monks were never alone. At meals, their spirits were distracted from the pleasures of the flesh and joined in the holy word by Saint Benedict’s prescribed reading.16

Coming together to be read to also became a necessary and common practice in the lay world of the Middle Ages. Up to the invention of printing, literacy was not widespread and books remained the property of the wealthy, the privilege of a small handful of readers. While some of these fortunate lords occasionally lent their books, they did so to a limited number of people within their own class or family.17 People who wished to acquaint themselves with a certain book or author often had a better chance of hearing the text recited or read out loud than of holding the precious volume in their own hands.

There were different ways to hear a text. Beginning in the eleventh century, throughout the kingdoms of Europe, travelling joglars would recite or sing their own verses or those composed by their master troubadours, which the joglars would have stored in their prodigious memories. These joglars were public entertainers who performed at fairs and market-places, as well as before the courts. They were mostly of lowly birth and were usually denied both the protection of the law and the sacraments of the Church.18 Troubadours, such as Guillaume of Aquitaine, grandfather of Eleanor, and Bertran de Born, Lord of Hautefort, were of noble birth and wrote formal songs in praise of their unreachable love. Of the hundred or so troubadours known by name from the early twelfth to the early thirteenth century, when the fashion flourished, some twenty were women. It seems that, in general, the joglars were more popular than the troubadours, so that highbrow artists such as Peter Pictor complained that “some of the high ecclesiasts would rather listen to the fatuous verses of a joglar than to the well-composed stanzas of a serious Latin poet”19 — meaning himself.

Being read to from a book was a somewhat different experience. A joglar’s recital had all the obvious characteristics of a performance, and its success or failure largely depended upon the performer’s skill at varying expressions, since the subject-matter was rather predictable. While a public reading also depended on the reader’s ability to “perform”, it laid the stress on the text rather than on the reader. The audience at a recital would watch a joglar perform the songs of a specific troubadour such as the celebrated Sordello; the audience at a public reading could listen to the anonymous History of Reynard the Fox read by any literate member of the household.

In the courts, and sometimes also in humbler houses, books were read aloud to family and friends for instruction as well as for entertainment. Being read to at dinner was not intended to distract from the joys of the palate; on the contrary, it was meant to enhance them with imaginative entertainment, a practice carried over from the days of the Roman empire. Pliny the Younger mentioned in one of his letters that, when eating with his wife or a few friends, he liked to have an amusing book read out loud to him.20 In the early fourteenth century the Countess Mahaut of Artois travelled with her library packed into large leather bags, and in the evenings she had a lady-in-waiting read from them, whether philosophical works or entertaining accounts of foreign lands such as the Travels of Marco Polo.21 Literate parents read to their children. In 1399 the Tuscan notary Ser Lapo Mazzei wrote to a friend, the merchant Francesco di Marco Datini, asking him for the loan of The Little Flowers of Saint Francis to read aloud to his sons. “The boys would take delight in it on winter evenings,” he explained, “for it is, as you know, very easy reading.”22 In Montaillou, in the early fourteenth century, Pierre Clergue, the village priest, read out loud on different occasions from a so-called Book of the Faith of the Heretics, to those sitting around the fire in people’s homes; in the village of Ax-les-Thermes, at about the same time, the peasant Guillaume Andorran was discovered reading a heretic Gospel to his mother and tried by the Inquisition.23

The fifteenth-century Évangiles des quenouilles (Gospels of the Distaffs) shows how fluid these informal readings could be. The narrator, an old learned man, “one night after supper, during the long winter nights between Christmas and Candlemas”, visits the house of an elderly lady, where several of the neighbourhood women often gather “to spin and talk about many happy and minor things”. The women, remarking that the men of their time “incessantly write defamatory lampoons and infectious books against the honour of the female sex,” ask the narrator to attend their meetings — a sort of reading group avant la lettre — and act as scrivener, while the women read out certain passages on the sexes, love affairs, marital relationships, superstitions and local customs, and comment on them from a female point of view. “One of us will begin her reading and read a few chapters to all the others present,” one of the spinners explains with enthusiasm, “so as to hold them and fix them permanently in our memories.”24 Over six days the women read, interrupt, comment, object and explain, and seem to enjoy themselves immensely, so much so that the narrator finds their laxity tiresome and, though faithfully recording their words, judges their comments “lacking rhyme or reason”. The narrator is, no doubt, accustomed to more formal scholastic disquisitions by men.

An early reading-group depicted in the sixteenth-century Les Evangiles des quenouilles. (photo credit 8.4)

Informal public readings at casual gatherings were quite ordinary occurrences in the seventeenth century. Stopping at an inn in search of the errant Don Quixote, the priest who has so diligently burnt the books in the knight’s library explains to the company how reading novels of chivalry has upset Don Quixote’s mind. The innkeeper objects to this statement, confessing that he very much enjoys listening to these stories in which the hero valiantly battles giants, strangles monstrous serpents and single-handedly defeats huge armies. “During harvest time,” he says, “during the festivities, many of the labourers gather here, and there are always a few among them who can read, and one of them will pick up one of these books in his hands, and more than thirty strong we will collect around him, and listen to him with such delight that our white hairs turn young again.” His daughter too is part of the audience, but she dislikes the scenes of violence; she prefers “to hear the lamentations the knights make when their ladies are absent, which in truth sometimes make me weep with pity for them”. A fellow traveller, who happens to have with him a number of novels of chivalry (which the priest wants to burn at once), also carries in his bags the manuscript of a novel. Somewhat against his will, the priest agrees to read it out loud for all those present. The title of the novel is, appropriately, The Curious Impertinent,25 and its reading occupies the three following chapters, while everyone feels free to interrupt and comment at will.26

So relaxed were these gatherings, so free of the strictures of institutionalized readings, that the listeners (or the reader) could mentally transfer the text to their own time and place. Two centuries after Cervantes, the Scottish publisher William Chambers wrote the biography of his brother Robert, with whom he had founded in 1832 the famous Edinburgh company that bears their name, and recollected certain such readings in their boyhood town of Peebles. “My brother and I,” he wrote, “derived much enjoyment, not to say instruction, from the singing of old ballads, and the telling of legendary stories, by a kind old female relative, the wife of a decayed tradesman, who dwelt in one of the ancient closes. At her humble fireside, under the canopy of a huge chimney, where her half-blind and superannuated husband sat dozing in a chair, the battle of Corunna and other prevailing news was strangely mingled with disquisitions on the Jewish wars. The source of this interesting conversation was a well-worn copy of L’Estrange’s translation of Josephus, a small folio of date 1720. The envied possessor of the work was Tam Fleck, ‘a flichty chield’, as he was considered, who, not particularly steady at his legitimate employment, stuck out a sort of profession by going about in the evening with his Josephus, which he read as the current news; the only light he had for doing so being usually that imparted by the flickering blaze of a piece of parrot coal. It was his practice not to read more than from two or three pages at a time, interlarded with sagacious remarks of his own by way of foot-notes, and in this way he sustained an extraordinary interest in the narrative. Retailing the matter with great equability in different households, Tam kept all at the same point of information, and wound them up with a corresponding anxiety as to the issue of some moving event in Hebrew annals. Although in this way he went through a course of Josephus yearly, the novelty somehow never seemed to wear off.”27

“Weel, Tam, what’s the news the nicht?” would old Geordie Murray say, as Tam entered with his Josephus under his arm, and seated himself at the family fireside.

“Bad news, bad news,” replied Tam. “Titus has begun to besiege Jerusalem — it’s gaun to be a terrible business.”28

During the act of reading (of interpreting, of reciting), possession of a book sometimes acquires talismanic value. In the north of France, even today, village story-tellers use books as props; they memorize the text, but then show authority by pretending to read from the book, even if they are holding it upside down.29 Something about the possession of a book — an object that can contain infinite fables, words of wisdom, chronicles of times gone by, humorous anecdotes and divine revelation — endows the reader with the power of creating a story, and the listener with a sense of being present at the moment of creation. What matters in these recitations is that the moment of reading be fully re-enacted — that is, with a reader, an audience and a book — without which the performance would not be complete.

In Saint Benedict’s day being read to was considered a spiritual exercise; in later centuries this lofty purpose could be used to conceal other, less seemly functions. For instance, in the early nineteenth century, when the notion of a scholarly woman was still frowned upon in Britain, being read to became one of the socially accepted ways of studying. The novelist Harriet Martineau lamented in her Autobiographical Memoir, published after her death in 1876, that “when she was young it was not thought proper for a young lady to study very conspicuously; she was expected to sit down in the parlour with her sewing, listen to a book read aloud, and hold herself ready for callers. When the callers came, conversation often turned naturally on the book just laid down, which must therefore be very carefully chosen lest the shocked visitor should carry to the house where she paid her next call an account of the deplorable laxity shown by the family she had left.”30

On the other hand, one might read out loud so as to produce this much-regretted laxity. In 1781, Diderot wrote amusingly about “curing” his bigoted wife, Nanette, who said she would not touch a book unless it contained something spiritually uplifting, by submitting her over several weeks to a diet of raunchy literature. “I have become her Reader. I administer three pinches of Gil Blas every day: one in the morning, one after dinner and one in the evening. When we have seen the end of Gil Blas we shall go on to The Devil on Two Sticks and The Bachelor of Salamanca and other cheering works of the same class. A few years and a few hundred such readings will complete the cure. If I were sure of success, I should not complain at the labour. What amuses me is that she treats everyone who visits her to a repeat of what I have just read her, so conversation doubles the effect of the remedy. I have always spoken of novels as frivolous productions, but I have finally discovered that they are good for the vapours. I will give Dr Tronchin the formula next time I see him. Prescription: eight to ten pages of Scarron’s Roman comique; four chapters of Don Quixote; a well-chosen paragraph from Rabelais; infuse in a reasonable quantity of Jacques the Fatalist or Manon Lescaut, and vary these drugs as one varies herbs, substituting others of roughly the same qualities, as necessary.”31

Being read to allows the listener a confidential audience for the reactions which must usually take place unheard, a cathartic experience which the Spanish novelist Benito Pérez Galdós described in one of his Episodios Nacionales. Doña Manuela, a nineteenth-century middle-class reader, retires to bed with the excuse of not wishing to become feverish by reading fully dressed under the light of the drawing-room lamp during a warm Madrid summer night. Her gallant admirer, General Leopoldo O’Donnell, offers to read to her out loud until she falls asleep, and chooses one of the pot-boilers that delight the lady, “one of those convoluted and muddled plots, badly translated from the French”. Guiding his eyes with his index finger, O’Donnell reads her the description of a duel in which a young blond man wounds a certain Monsieur Massenot:

“How wonderful!” Doña Manuela exclaimed, enraptured. “That blond fellow, don’t you remember, is the artilleryman who came from Brittany disguised as a pedlar. By his looks, he must be the natural son of the duchess.… Carry on.… But according to what you just read,” Doña Manuela observed, “you mean to say he cut off Massenot’s nose?”

“So it seems.… It says clearly: ‘Massenot’s face was covered with blood which ran like two rivulets across his greying moustache.’ ”

“I’m delighted.… Serves him right, and let him come back for more. Now let’s see what else the author will tell us.”32

Because reading out loud is not a private act, the choice of reading material must be socially acceptable to both the reader and the audience. At Steventon rectory, in Hampshire, the Austen family read to one another at all times of the day and commented on the appropriateness of each selection. “My father reads Cowper to us in the mornings, to which I listen when I can,” Jane Austen wrote in 1808. “We have got the second volume of [Southey’s] Espriella’s Letters and I read it aloud by candlelight.” “Ought I to be very pleased with [Sir Walter Scott’s] Marmion? As yet I am not. James [the eldest brother] reads it aloud every evening — the short evening, beginning about ten, and broken by supper.” Listening to Madame de Genlis’s Alphonsine, Austen is outraged: “We were disgusted in twenty pages, as, independent of a bad translation, it has indelicacies which disgrace a pen hitherto so pure; and we changed it for [Lennox’s] the Female Quixote, which now makes our evening amusement, to me a very high one, as I find the work quite equal to what I remember it.”33 (Later, in Austen’s writings, there will be echoes of these books she has heard read out loud, in direct references made by characters defined through their bookish likes or dislikes: Sir Edward Denham dismisses Scott as “tame” in Sanditon, and in Northanger Abbey John Thorpe remarks, “I never read novels” — though he immediately confesses to finding Fielding’s Tom Jones and Lewis’s The Monk “tolerably decent”.)

Being read to for the purpose of purifying the body, being read to for pleasure, being read to for instruction or to grant the sounds supremacy over the sense, both enrich and diminish the act of reading. Allowing someone else to speak the words on a page for us is an experience far less personal than holding the book and following the text with our own eyes. Surrendering to the reader’s voice — except when the listener’s personality is overwhelming — removes our ability to establish a certain pace for the book, a tone, an intonation that is unique to each person. It condemns the ear to someone else’s tongue, and in that act a hierarchy is established (sometimes made apparent in the reader’s privileged position, in a separate chair or on a podium) which places the listener in the reader’s grip. Even physically, the listener will often follow the reader’s cue. Describing a reading among friends, Diderot wrote in 1759, “Without conscious thought on either’s part, the reader disposes himself in the manner he finds most appropriate, and the listener does the same.… Add a third character to the scene, and he will submit to the law of the two former: it is a combined system of three interests.”34

At the same time, the act of reading out loud to an attentive listener often forces the reader to become more punctilious, to read without skipping or going back to a previous passage, fixing the text by means of a certain ritual formality. Whether in the Benedictine monasteries or the winter rooms of the late Middle Ages, in the inns and kitchens of the Renaissance or the drawing-rooms and cigar factories of the nineteenth century — even today, listening to an actor read a book on tape as we drive down the highway — the ceremony of being read to no doubt deprives the listener of some of the freedom inherent in the act of reading — choosing a tone, stressing a point, returning to a best-loved passage — but it also gives the versatile text a respectable identity, a sense of unity in time and an existence in space that it seldom has in the capricious hands of a solitary reader.

Master-printer Aldus Manutius. (photo credit 8.5)