y hands, choosing a book to take to bed or to the reading-desk, for the train or for a gift, consider the form as much as the content. Depending on the occasion, depending on the place where I’ve chosen to read, I prefer something small and cosy or ample and substantial. Books declare themselves through their titles, their authors, their places in a catalogue or on a bookshelf, the illustrations on their jackets; books also declare themselves through their size. At different times and in different places I have come to expect certain books to look a certain way, and, as in all fashions, these changing features fix a precise quality onto a book’s definition. I judge a book by its cover; I judge a book by its shape.

y hands, choosing a book to take to bed or to the reading-desk, for the train or for a gift, consider the form as much as the content. Depending on the occasion, depending on the place where I’ve chosen to read, I prefer something small and cosy or ample and substantial. Books declare themselves through their titles, their authors, their places in a catalogue or on a bookshelf, the illustrations on their jackets; books also declare themselves through their size. At different times and in different places I have come to expect certain books to look a certain way, and, as in all fashions, these changing features fix a precise quality onto a book’s definition. I judge a book by its cover; I judge a book by its shape.

From the very beginning, readers demanded books in formats adapted to their intended use. The early Mesopotamian tablets were usually square but sometimes oblong pads of clay, approximately 3 inches across, and could be held comfortably in the hand. A book consisted of several such tablets, kept perhaps in a leather pouch or box, so that a reader could pick up tablet after tablet in a predetermined order. It is possible that the Mesopotamians also had books bound in much the same way as our volumes; neo-Hittite funerary stone monuments depict some objects resembling codexes — perhaps a series of tablets bound together inside a cover — but no such book has come down to us.

Not all Mesopotamian books were meant to be held in the hand. There exist texts written on much larger surfaces, such as the Middle Assyrian Code of Laws, found in Ashur and dating from the twelfth century BC, which measures 67 square feet and carries its text in columns on both sides.1 Obviously this “book” was not meant to be handled, but to be erected and consulted as a work of reference. In this case, size must also have carried a hierarchic significance; a small tablet might suggest a private transaction; a book of laws in such a large format surely added, in the eyes of the Mesopotamian reader, to the authority of the laws themselves.

Of course, whatever a reader might have desired, the format of a book was limited. Clay was convenient for manufacturing tablets, and papyrus (the dried and split stems of a reed-like plant) could be made into manageable scrolls; both were relatively portable. But neither was suitable for the form of book that superseded tablet and scroll: the codex, or sheaf of bound pages. A codex of clay tablets would have been heavy and cumbersome, and although there were codexes made of papyrus pages, papyrus was too brittle to be folded into booklets. Parchment, on the other hand, or vellum (both made from the skins of animals, through different procedures), could be cut up or folded into all sorts of different sizes. According to Pliny the Elder, King Ptolemy of Egypt, wishing to keep the production of papyrus a national secret in order to favour his own Library of Alexandria, forbade its export, thereby forcing his rival, Eumenes, ruler of Pergamum, to find a new material for the books in his library.2 If Pliny is to be believed, King Ptolemy’s edict led to the invention of parchment in Pergamum in the second century BC, although the earliest parchment booklets known to us today date from a century earlier.3 These materials were not used exclusively for one kind of book: there were scrolls made out of parchment and, as we have said, codexes made out of papyrus; but these were rare and impractical. By the fourth century, and until the appearance of paper in Italy eight centuries later, parchment was the preferred material throughout Europe for the making of books. Not only was it sturdier and smoother than papyrus, it was also cheaper, since a reader who demanded books written on papyrus (notwithstanding King Ptolemy’s edict) would have had to import the material from Egypt at considerable cost.

The parchment codex quickly became the common form of books for officials and priests, travellers and students — in fact for all those who needed to transport their reading material conveniently from one place to another, and to consult any section of the text with ease. Furthermore, both sides of the leaf could hold text, and the four margins of a codex page made it easier to include glosses and commentaries, allowing the reader a hand in the story — a participation that was far more difficult when reading from a scroll. The organization of the texts themselves, which had previously been divided according to the capacity of a scroll (in the case of Homer’s Iliad, for instance, the division of the poem into twenty-four books probably resulted from the fact that it normally occupied twenty-four scrolls), was changed. The text could now be organized according to its contents, in books or chapters, or could become itself a component when several shorter works were conveniently collected under a single handy cover. The unwieldy scroll possessed a limited surface — a disadvantage we are keenly aware of today, having returned to this ancient book-form on our computer screens, which reveal only a portion of text at a time as we “scroll” upwards or downwards. The codex, on the other hand, allowed the reader to flip almost instantly to other pages, and thereby retain a sense of the whole — a sense compounded by the fact that the entire text was usually held in the reader’s hands throughout the reading. The codex had other extraordinary merits: originally intended to be transported with ease, and therefore necessarily small, it grew in both size and number of pages, becoming, if not limitless, at least much vaster than any previous book. The first-century poet Martial wondered at the magical powers of an object small enough to fit in the hand and yet containing an infinity of marvels:

Homer on parchment pages!

The Iliad and all the adventures

Of Ulysses, foe of Priam’s kingdom!

All locked within a piece of skin

Folded into several little sheets!4

The codex’s advantages prevailed: by AD 400, the classical scroll had been all but abandoned and most books were being produced as gathered leaves in a rectangular format. Folded once, the parchment became a folio; folded twice, a quarto; folded once again, an octavo. By the sixteenth century, the formats of the folded sheets had become official: in France, in 1527, François I decreed standard paper sizes throughout his kingdom; anyone breaking this rule was thrown into prison.5

Of all the shapes that books have acquired through the ages, the most popular have been those that allowed the book to be held comfortably in the reader’s hand. Even in Greece and Rome, where scrolls were normally used for all kinds of texts, private missives were usually written on small, hand-held reusable wax tablets, protected by raised edges and decorated covers. In time, the tablets gave way to a few gathered leaves of fine parchment, sometimes of different colours, for the purpose of jotting down quick notes or doing sums. In Rome, towards the third century AD, these booklets lost their practical value and became prized instead for the look of their covers. Bound in finely decorated flats of ivory, they were offered as gifts to high officials on their nomination to office; eventually they became private gifts as well, and wealthy citizens began giving each other booklets in which they would inscribe a poem or dedication. Soon, enterprising booksellers started manufacturing small collections of poems in this manner — little gift books whose merit lay less in the contents than in the elaborate embellishments.6

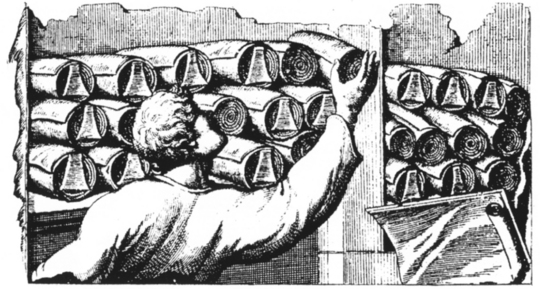

Engraving copied from a bas-relief showing a method for storing scrolls in ancient Rome. Note the name-tags hanging from the ends of the scrolls. (photo credit 9.1)

The size of a book, whether it was a scroll or a codex, determined the shape of the place in which it was kept. Scrolls were put away either in wooden scroll boxes (which resembled hat-boxes of a sort) with labels which were made of clay in Egypt and of parchment in Rome, or in bookcases with their tags (the index or titulus) showing, so that the book could be easily identified. Codexes were stored lying flat, on shelves made for that purpose. Describing a visit to a country house in Gaul around AD 470, Gaius Sollius Apollinaris Sidonius, Bishop of Auvergne, mentioned a number of bookcases which varied according to the sizes of the codexes they were meant to hold: “Here too were books in plenty; you might fancy you were looking at the breast-high bookshelves (plantei) of the grammarians, or the wedge-shaped cases (cunei) of the Atheneum, or the well-filled cupboards (armaria) of the booksellers.”7 According to Sidonius, the books he found there were of two kinds: Latin classics for the men and books of devotion for the women.

Since much of the life of Europeans in the Middle Ages was spent in religious offices, it is hardly surprising that one of the most popular books of the time was the personal prayer-book, or Book of Hours, which was commonly represented in depictions of the Annunciation. Usually handwritten or printed in a small format, in many cases illuminated with exquisite richness by master artists, it contained a collection of short services known as “the Little Office of the Blessed Virgin Mary”, recited at various times of the night and day.8 Modelled on the Divine Office — the fuller services said daily by the clergy — the Little Office comprised Psalms and other passages from the Scriptures, as well as hymns, the Office of the Dead, special prayers to the saints and a calendar. These small volumes were eminently portable tools of devotion which the faithful could use either in public church services or in private prayers. Their size made them suitable for children; around 1493, the Duke Gian Galeazzo Sforza of Milan had a Book of Hours designed for his three-year-old son, Francesco Maria Sforza, “Il Duchetto”, depicted on one of the pages as being led by a guardian angel through a night-time wilderness. The Books of Hours were richly but variably decorated, depending on who the customers were and how much they could afford to pay. Many depicted the commissioning of the family’s coat-of-arms, or a portrait of the reader. Books of Hours became conventional wedding gifts for the nobility and, later, for the rich bourgeoisie. By the end of the fifteenth century, the book illuminators of Flanders dominated the European market, sending trade delegations throughout Europe to establish the equivalent of our wedding-gift lists.9 The beautiful Book of Hours commissioned for the wedding of Anne of Brittany in 1490 was made to the size of her hand.10 It is designed for a single reader absorbed in both the words of the prayers repeated month after month and year after year, and the ever-surprising illustrations, whose details would never be utterly deciphered and whose urbanity — the Old and New Testament scenes took place in modern landscapes — brought the sacred words into a setting contemporary with the reader herself.

A personalized illumination showing the child Francesco Maria Sforza with his guardian angel in a Book of Hours made especially for him. (photo credit 9.2)

In the same way that small volumes served specific purposes, large volumes met other readers’ demands. Around the fifth century, the Catholic Church began producing huge service-books — missals, chorales, antiphonaries — which, displayed on a lectern in the middle of the choir, allowed readers to follow the words or musical notes with as much ease as if they were reading a monumental inscription. There is a beautiful antiphonary in the Abbey Library of St. Gall, containing a selection of liturgical texts in lettering so large that it can be read at a fair distance, to the cadence of melodic chants, by choirs of up to twenty singers;11 standing several feet back from it, I can make out the notes with absolute clarity, and I wish my own reference books could be consulted with such ease from afar. Some of these service-books were so immense that they had to be laid on rollers so they could be moved. But they were moved very rarely. Decorated with brass or ivory, protected with corners of metal, closed by gigantic clasps, they were books to be read communally and at a distance, disallowing any intimate perusal or sense of personal possession.

A fifteenth-century depiction of a group of choirboys reading the large-size notes of an antiphonary. (photo credit 9.3)

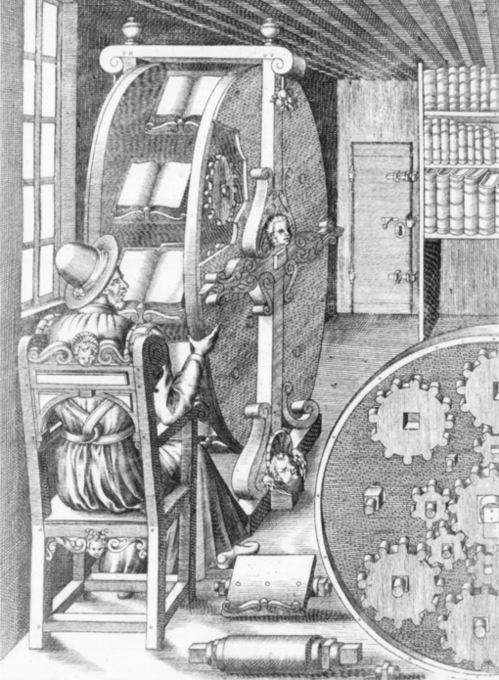

Saint Gregory’s mechanical reading-desk as imagined by a fourteenth-century sculptor. (photo credit 9.4)

In order to be able to read a book comfortably, readers invented ingenious improvements on the lectern and the desk. There is a statue of Saint Gregory the Great, made of pigmental stone in Verona sometime in the fourteenth century and preserved in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, showing the saint at a sort of articulated reading-desk which would have enabled him to prop the lectern at different angles or raise it in order to leave his seat. A fourteenth-century engraving shows a scholar in a book-lined library writing at an elevated, octagonal desk-cum-lectern that allows him to work on one side, then swivel the desk and read the books laid ready for him on the seven other sides. In 1588 an Italian engineer, Agostino Ramelli, serving under the King of France, published a book describing a series of useful machines. One of these is a “rotary reading desk” which Ramelli describes as “a beautiful and ingenious machine, which is very useful and convenient to every person who takes pleasure in study, especially those who are suffering from indisposition or are subject to gout: for with this sort of machine a man can see and read a great quantity of books, without moving his place: besides, it has this fine convenience, which is, of occupying little space in the place where it is set, as any person of understanding can appreciate from the drawing”.12 (A full-scale model of this marvellous reading-wheel appeared in Richard Lester’s 1974 film The Three Musketeers.) Seat and reading-desk could be combined in a single piece of furniture. The ingenious cockfighting chair (so called because it was depicted in illustrations of cockfighting) was made in England in the early eighteenth century, specifically for libraries. The reader sat astride it, facing the desk at the back of the chair while leaning on the broad armrests for support and comfort.

Mahogany cockfighting chair with leather upholstery, c. 1720. (photo credit 9.5)

A clever reading-machine from the 1588 edition of Diverse et Artificiose Machine. (photo credit 9.6)

Sometimes a reading-device would be invented out of a different kind of necessity. Benjamin Franklin relates that, during Queen Mary’s reign, his Protestant ancestors would hide their English bible, “fastened open with tapes under and within the cover of a joint-stool”. Whenever Franklin’s great-great-grandfather read to the family, “he turned up the joint-stool upon his knees, turning over the leaves then under the tapes. One of the children stood at the door to give notice if he saw the apparitor coming, who was an officer of the spiritual court. In that case the stool was turned down again upon its feet, when the Bible remained concealed under it as before.”13

Crafting a book, whether the elephantine volumes chained to the lecterns or the dainty booklets made for a child’s hand, was a long, laborious process. A change that took place in mid-fifteenth-century Europe not only reduced the number of working-hours needed to produce a book, but dramatically increased the output of books, altering for ever the reader’s relationship to what was no longer an exclusive and unique object crafted by the hands of a scribe. The change, of course, was the invention of printing.

Sometime in the 1440s, a young engraver and gem-cutter from the Archbishopric of Mainz, whose full name was Johannes Gensfleisch zur Laden zum Gutenberg (which the practicalities of the business world trimmed down to Johann Gutenberg), realized that much could be gained in speed and efficiency if the letters of the alphabet were cut in the form of reusable type rather than as the woodcut blocks which were then being used occasionally for printing illustrations. Gutenberg experimented over several years, borrowing large sums of money to finance his enterprise. He succeeded in devising all the essentials of printing as they were employed until the twentieth century: metal prisms for moulding the faces of the letters, a press that combined features of those used in wine-making and bookbinding, and an oil-based ink — none of which had previously existed.14 Finally, between 1450 and 1455, Gutenberg produced a bible with forty-two lines to each page — the first book ever printed from type15 — and took the printed pages with him to the Frankfurt Trade Fair. By an extraordinary stroke of luck, we have a letter from a certain Enea Silvio Piccolomini to the Cardinal of Carvajal, dated March 12, 1455, in Wiener Neustadt, telling His Eminence that he has seen Gutenberg’s bible at the fair:

I did not see any complete Bibles, but I did see a certain number of five-page booklets [signatures] of several of the books of the Bible, with very clear and very proper lettering, and without any faults, which Your Eminence would have been able to read effortlessly with no glasses. Various witnesses told me that 158 copies had been completed, while others say there were 180. I am not certain of the quantity, but about the books’ completion, if people can be trusted, I have no doubts whatsoever. Had I known your wishes, I would certainly have bought a copy. Several of these five-page booklets were sent to the Emperor himself. I shall try, as far as possible, to have one of these Bibles delivered for sale and I will purchase one copy for you. But I am afraid that this may not be possible, both because of the distance and because, so they say, even before the books were finished, there were customers ready to buy them.16

An imaginary portrait of Johann Gutenberg. (photo credit 9.7)

The effects of Gutenberg’s invention were immediate and extraordinarily far-reaching, for almost at once many readers realized its great advantages: speed, uniformity of texts and relative cheapness.17 Barely a few years after the first bible had been printed, printing presses were set up all over Europe: in 1465 in Italy, 1470 in France, 1472 in Spain, 1475 in Holland and England, 1489 in Denmark. (Printing took longer to reach the New World: the first presses were established in 1533 in Mexico City and in 1638 in Cambridge, Massachusetts.) It has been calculated that more than 30,000 incunabula (a seventeenth-century Latin word meaning “related to the cradle” and used to describe books printed before 1500) were produced on these presses.18 Considering that fifteenth-century print-runs were usually of fewer than 250 copies and hardly ever reached 1,000, Gutenberg’s feat must be seen as prodigious.19 Suddenly, for the first time since the invention of writing, it was possible to produce reading material quickly and in vast quantities.

It may be useful to bear in mind that printing did not, in spite of the obvious “end-of-the-world” predictions, eradicate the taste for handwritten text. On the contrary, Gutenberg and his followers attempted to emulate the scribe’s craft, and most incunabula have a manuscript appearance. At the end of the fifteenth century, even though printing was by then well established, care for the elegant hand had not died out, and some of the most memorable examples of calligraphy still lay in the future. While books were becoming more easily available and more people were learning to read, more were also learning to write, often stylishly and with great distinction, and the sixteenth century became not only the age of the printed word but also the century of the great manuals of handwriting.20 It is interesting to note how often a technological development — such as Gutenberg’s — promotes rather than eliminates that which it is supposed to supersede, making us aware of old-fashioned virtues we might otherwise have either overlooked or dismissed as of negligible importance. In our day, computer technology and the proliferation of books on CD-ROM have not affected — as far as statistics show — the production and sale of books in their old-fashioned codex form. Those who see computer development as the devil incarnate (as Sven Birkerts portrays it in his dramatically titled Gutenberg Elegies)21 allow nostalgia to hold sway over experience. For example, 359,437 new books (not counting pamphlets, magazines and periodicals), were added in 1995 to the already vast collections of the Library of Congress.

The sudden increase in book production after Gutenberg emphasized the relation between the contents of a book and its physical form. For instance, since Gutenberg’s bible was intended to imitate the expensive handmade volumes of the time, it was bought in gathered sheets and bound by its purchasers into large, imposing tomes — usually quartos measuring about 12 by 16 inches,22 meant to be displayed on a lectern. A bible of this size in vellum would have required the skins of more than two hundred sheep (“a sure cure for insomnia,” commented the antiquarian bookseller Alan G. Thomas).23 But cheap and quick production led to a larger market of people who could afford copies to read privately, and who therefore did not require books in large type and format, and Gutenberg’s successors eventually began producing smaller, pocketable volumes.

In 1453 Constantinople fell to the Ottoman Turks, and many of the Greek scholars who had established schools on the shores of the Bosphorus left for Italy. Venice became the new centre of classical learning. Some forty years later the Italian humanist Aldus Manutius, who had instructed such brilliant students as Pico della Mirandola in Latin and Greek, finding it difficult to teach without scholarly editions of the classics in practical formats, decided to take up Gutenberg’s craft and established a printing-house of his own where he would be able to produce exactly the kind of books he needed for his courses. Aldus chose to establish his press in Venice in order to take advantage of the presence of the displaced Eastern scholars, and probably employed as correctors and compositors other exiles, Cretan refugees who had formerly been scribes.24 In 1494 Aldus began his ambitious publishing program, which was to produce some of the most beautiful volumes in the history of printing: first in Greek — Sophocles, Aristotle, Plato, Thucydides — and then in Latin — Virgil, Horace, Ovid. In Aldus’s view, these illustrious authors were to be read “without intermediaries” — in the original tongue, and mostly without annotations or glosses — and to make it possible for readers to “converse freely with the glorious dead” he published grammar books and dictionaries alongside the classical texts.25 Not only did he seek the services of local experts, he also invited eminent humanists from all over Europe — including such luminaries as Erasmus of Rotterdam — to stay with him in Venice. Once a day these scholars would meet in Aldus’s house to discuss what titles would be printed and what manuscripts would be used as reliable sources, sifting through the collections of classics established in the previous centuries. “Where medieval humanists accumulated,” noted the historian Anthony Grafton, “Renaissance ones discriminated.”26 Aldus discriminated with an unerring eye. To the list of classical writers he added the works of the great Italian poets, Dante and Petrarch among others.

An elegant example of Aldus’s work: the sober beauty of Cicero’s Epistolae Familiares. (photo credit 9.8)

As private libraries grew, readers began to find large volumes not only difficult to handle and uncomfortable to carry, but inconvenient to store. In 1501, confident in the success of his first editions, Aldus responded to readers’ demands and brought out a series of pocket-sized books in octavo — half the size of quarto — elegantly printed and meticulously edited. To keep down the production costs he decided to print a thousand copies at a time, and to use the page more economically he employed a newly designed type, “italic”, created by the Bolognese punch-cutter Francesco Griffo, who also cut the first roman type in which the capitals were shorter than the ascending (full-height) letters of the lower case to ensure a better-balanced line. The result was a book that appeared much plainer than the ornate manuscript editions popular throughout the Middle Ages, a volume of elegant sobriety. What counted above all, for the owner of an Aldine pocket-book, was the text, clearly and eruditely printed — not a preciously decorated object.27 Griffo’s italic type (first used in a woodcut illustrating a collection of letters of Saint Catherine of Siena, printed in 1500) gracefully drew the reader’s attention to the delicate relationship between letters; according to the modern English critic Sir Francis Meynell, italics slowed down the reader’s eye, “increasing his capacity to absorb the beauty of the text”.28

On the open book and on the heart held by Saint Catherine, the earliest use of Griffo’s italics, in an Aldine edition of the Saint’s letters. (photo credit 9.9)

Since these books were cheaper than manuscripts, especially illuminated ones, and since an identical replacement could be purchased if a copy was lost or damaged, they became, in the eyes of the new readers, less symbols of wealth than of intellectual aristocracy, and essential tools for study. Booksellers and stationers had produced, both in the days of ancient Rome and in the early Middle Ages, books as merchandise to be traded, but the cost and pace of their production weighed upon the readers with a sense of privilege in owning something unique. After Gutenberg, for the first time in history, hundreds of readers possessed identical copies of the same book, and (until a reader gave a volume private markings and a personal history) the book read by someone in Madrid was the same book read by someone in Montpellier. So successful was Aldus’s enterprise that his editions were soon being imitated throughout Europe: in France by Gryphius in Lyons, as well as Colines and Robert Estienne in Paris, and in The Netherlands by Plantin in Antwerp and Elzevir in Leiden, The Hague, Utrecht and Amsterdam. When Aldus died in 1515, the humanists who attended his funeral erected all around his coffin, like erudite sentinels, the books he had so lovingly chosen to print.

The example of Aldus and others like him set the standard for at least a hundred years of printing in Europe. But in the next couple of centuries the readers’ demands once again changed. The numerous editions of books of every kind offered too large a choice; competition between publishers, which up to then had merely encouraged better editions and greater public interest, began producing books of vastly impoverished quality. By the mid-sixteenth century, a reader would have been able to choose from well over eight million printed books, “more perhaps than all the scribes of Europe had produced since Constantine founded his city in AD 330.”29 Obviously these changes were neither sudden nor all-pervasive, but in general, from the end of the sixteenth century, “publisher-booksellers were no longer concerned with patronizing the world of letters, but merely sought to publish books whose sale was guaranteed. The richest made their fortune on books with a guaranteed market, reprints of old best-sellers, traditional religious works and, above all, the Church Fathers.”30 Others cornered the school market with glosses of scholarly lectures, grammar manuals and sheets for hornbooks.

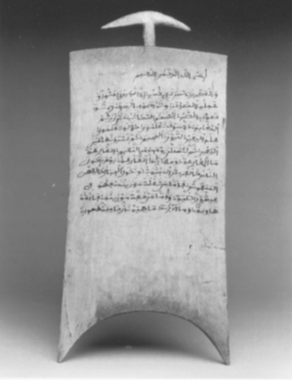

The hornbook, in use from the sixteenth to the nineteenth century, was generally the first book put in a student’s hand. Very few have survived to our time. The hornbook consisted of a thin board of wood, usually oak, about nine inches long and five or six inches wide, bearing a sheet on which were printed the alphabet, and sometimes the nine digits and the Lord’s Prayer. It had a handle, and was covered in front by a transparent layer of horn to prevent it from becoming dirty; the board and the sheet of horn were then held together by a thin brass frame. The English landscape gardener and doubtful poet William Shenstone describes the principle in The Schoolmistress, in these words:

An Elizabethan hornbook which miraculously survived four centuries of children’s hands. (photo credit 9.10)

Its nineteenth-century Nigerian counterpart. (photo credit 9.11)

Their books of stature small they took in hand,

Which with pellucid horn securèd are,

To save from finger wet the letter fair.31

Similar books, known as “prayer boards”, were used in Nigeria in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries to teach the Koran. They were made of polished wood, with a handle at the top; the verses were written on a sheet of paper pasted directly onto the board.32

Books one could slip into one’s pocket; books in a companionable shape; books that the reader felt could be read in any number of places; books that would not be judged awkward outside a library or a cloister: these books appeared under all kinds of guises. Throughout the seventeenth century, hawkers sold little booklets and ballads (described in The Winter’s Tale as suitable “for man, or woman, of all sizes”)33 which became known as chap-books34 in the following century. The preferred size of popular books had been the octavo, since a single sheet could produce a booklet of sixteen pages. In the eighteenth century, perhaps because readers now demanded fuller accounts of the events narrated in tales and ballads, the sheets were folded in twelve parts and the booklets were fattened to twenty-four paperback pages.35 The classic series produced by Elzevir of Holland in this format achieved such popularity among less well-off readers that the snobbish Earl of Chesterfield was led to comment, “If you happen to have an Elzevir classic in your pocket, neither show it nor mention it.”36

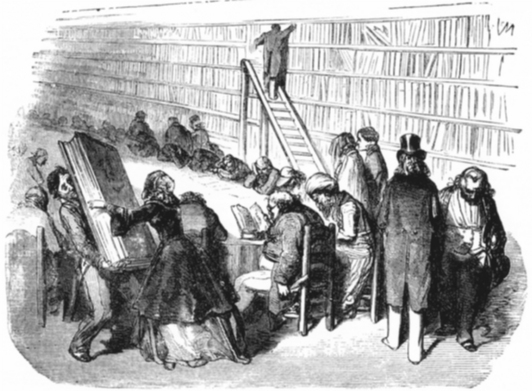

The pocket paperback as we now know it did not come into being until much later. The Victorian age, which saw the formation in England of the Publishers’ Association, the Booksellers’ Association, the first commercial agencies, the Society of Authors, the royalty system and the one-volume, six-shilling new novel, also witnessed the birth of the pocket-book series.37 Large-format books, however, continued to encumber the shelves. In the nineteenth century, so many books were being published in huge formats that a Gustave Doré cartoon depicted a poor clerk at the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris trying to move a single one of these huge tomes. Binding cloth replaced the costly leather (the English publisher Pickering was the first to use it, in his Diamond Classics of 1822) and, since the cloth could be printed upon, it was soon employed to carry advertising. The object that the reader now held in his hand — a popular novel or science manual in a comfortable octavo bound in blue cloth, sometimes protected with paper wrappers on which ads might also be printed — was very different from the morocco-bound volumes of the preceding century. Now the book was a less aristocratic object, less forbidding, less grand. It shared with the reader a certain middle-class elegance that was economical and yet pleasing — a style which the designer William Morris would turn into a popular industry but which ultimately — in Morris’s case — became a new luxury: a style based on the conventional beauty of everyday things. (Morris in fact modelled his ideal book on one of Aldus’s volumes.) In the new books which the mid-nineteenth-century reader expected, the measure of excellence was not rarity but an alliance of pleasure and sober practicality. Private libraries were now appearing in bed-sitters and semi-detached homes, and their books suited the social standing of the rest of the furnishings.

The booklet hawker, a sixteenth-century walking bookshop. (photo credit 9.12)

A Gustave Doré caricature satirizing the new European fad for large-sized books. (photo credit 9.13)

In seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Europe, it had been assumed that books were meant to be read indoors, within the secluding walls of a private or public library. Now publishers were producing books meant to be taken out into the open, books made specifically to travel. In nineteenth-century England, the newly leisured bourgeoisie and the expansion of the railway combined to create a sudden urge for long journeys, and literate travellers found that they required reading material of specific content and size. (A century later, my father was still making a distinction between the green leather-bound books of his library, which no one was allowed to remove from that sanctuary, and the “ordinary paperbacks” which he left to yellow and wither on the wicker table on the patio, and which I would sometimes rescue and bring into my room as if they were stray cats.)

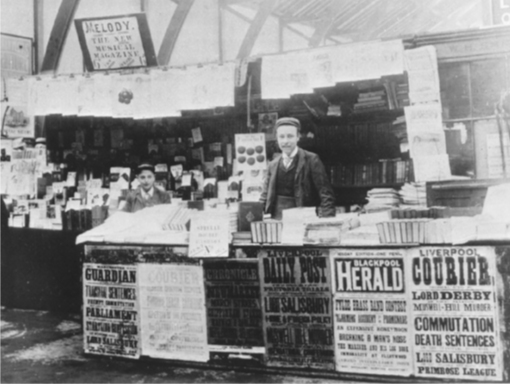

In 1792, Henry Walton Smith and his wife, Anna, opened a small news-vendor’s shop in Little Grosvenor Street in London. Fifty-six years later W.H. Smith & Son opened the first railway bookstall, at Euston Station in London. It was soon stocking such series as Routledge’s Railway Library, the Travellers’ Library, the Run & Read Library and the Illustrated Novels and Celebrated Works series. The format of these books varied slightly, but they were mainly octavos, with a few (Dickens’s A Christmas Carol, for example) issued as smaller demi-octavo, and bound in cardboard. The bookstalls (to judge by a photograph of W.H. Smith’s stall at Blackpool North, taken in 1896) sold not only these books but magazines and newspapers, so that travellers would have ample choice of reading material.

The W.H. Smith railway bookstall at Blackpool North Station, London, 1896. (photo credit 9.14)

In 1841, Christian Bernhard Tauchnitz of Leipzig had launched one of the most ambitious of all paperback series; at an average of one title a week it published more than five thousand volumes in its first hundred years, bringing its circulation to somewhere between fifty and sixty million copies. While the choice of titles was excellent, the production was not equal to their content. The books were squarish, set in tiny type, with identical typographical covers that appealed neither to the hand nor to the eye.38

Seventeen years later, Reclam Publishers in Leipzig published a twelve-volume edition of Shakespeare in translation. It was an immediate success, which Reclam followed by subdividing the edition into twenty-five little volumes of the plays in pink paper covers at the sensational price of one decimal pfennig each. All works by German writers dead for thirty years came into the public domain in 1867, and this allowed Reclam to continue the series under the title Universal-Bibliothek. The company began with Goethe’s Faust, and continued with Gogol, Pushkin, Bjørnson, Ibsen, Plato and Kant. In England, imitative reprint series of “the classics” — Nelson’s New Century Library, Grant Richards’s World’s Classics, Collins’s Pocket Classics, Dent’s Everyman’s Library — rivalled but did not overshadow the success of the Universal-Bibliothek,39 which remained for years the standard paperback series.

Until 1935. One year earlier, after a weekend spent with Agatha Christie and her second husband in their house in Devon, the English publisher Allen Lane, waiting for his train back to London, looked through the bookstalls at the station for something to read. He found nothing that appealed to him among the popular magazines, the expensive hardbacks and the pulp fiction, and it occurred to him that what was needed was a line of cheap but good pocket-sized books. Back at The Bodley Head, where Lane worked with his two brothers, he put forward his scheme. They would publish a series of brightly coloured paperback reprints of the best authors. They would not merely appeal to the common reader; they would tempt everyone who could read, highbrows and lowbrows alike. They would sell books not only in bookstores and bookstalls, but also at tea-shops, stationers and tobacconists.

The project met with contempt both from Lane’s senior colleagues at The Bodley Head and from his fellow publishers, who had no interest in selling him reprint rights to their hardcover successes. Neither were booksellers enthusiastic, since their profits would be diminished and the books themselves “pocketed” in the reprehensible sense of the word. But Lane persevered, and in the end obtained permission to reprint several titles: two published already by The Bodley Head — André Maurois’s Ariel and Agatha Christie’s The Mysterious Affair at Styles — and others by such best-selling authors as Ernest Hemingway and Dorothy L. Sayers, plus a few by writers who are today less known, such as Susan Ertz and E.H. Young.

What Lane now needed was a name for his series, “not formidable like World Classics, not somehow patronizing like Everyman”.40 The first choices were zoological: a dolphin, then a porpoise (already used by Faber & Faber) and finally a penguin. Penguin it was.

On July 30, 1935, the first ten Penguins were launched at sixpence a volume. Lane had calculated that he would break even after seventeen thousand copies of each title were sold, but the first sales brought the number only to about seven thousand. He went to see the buyer for the vast Woolworth general store chain, a Mr. Clifford Prescott, who demurred; the idea of selling books like any other merchandise, together with sets of socks and tins of tea, seemed to him somehow ludicrous. By chance, at that very moment Mrs. Prescott entered her husband’s office. Asked what she thought, she responded enthusiastically. Why not, she asked. Why should books not be treated as everyday objects, as necessary and as available as socks and tea? Thanks to Mrs. Prescott, the sale was made. George Orwell summed up his reaction, both as reader and as author, to these newcomers. “In my capacity as reader,” he wrote, “I applaud the Penguin Books; in my capacity as writer I pronounce them anathema.… The result may be a flood of cheap reprints which will cripple the lending libraries (the novelist’s foster-mother) and check the output of new novels. This would be a fine thing for literature, but a very bad thing for trade.”41 He was wrong. More than its specific qualities (its vast distribution, its low cost, the excellence and wide range of its titles), Penguin’s greatest achievement was symbolic. The knowledge that such a huge range of literature could be bought by almost anyone almost anywhere, from Tunis to Tucumán, from the Cook Islands to Reykjavik (such are the fruits of British expansionism that I have bought and read a Penguin in all these places), lent readers a symbol of their own ubiquity.

The first ten Penguins. (photo credit 9.15)

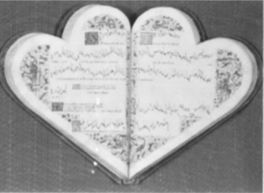

A fifteenth-century heart-shaped book of madrigals. (photo credit 9.16)

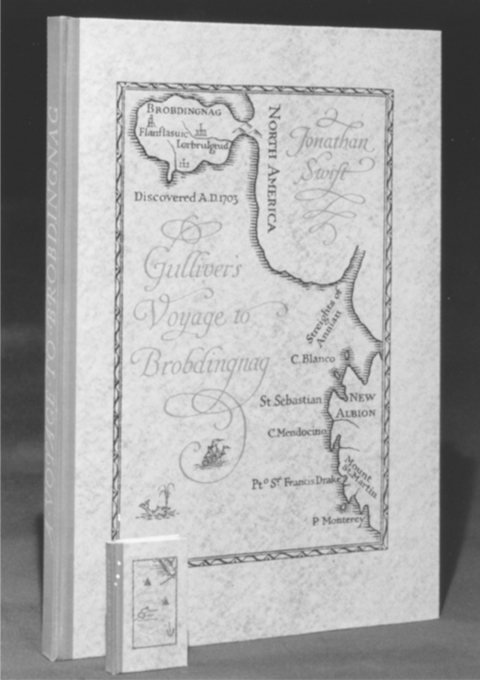

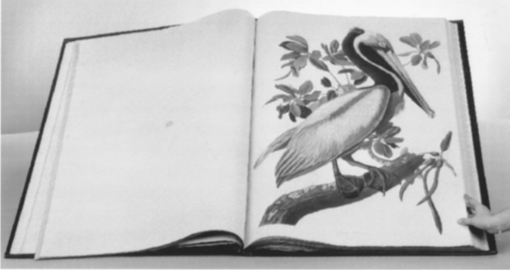

The invention of new shapes for books is probably endless, and yet very few odd shapes survive. The heart-shaped book fashioned towards 1475 by a noble cleric, Jean de Montchenu, containing illuminated love lyrics; the minuscule booklet held in the right hand of a young Dutch woman of the mid-seventeeth century painted by Bartholomeus van der Helst; the world’s tiniest book, the Bloemhofje or Enclosed Flower-Garden, written in Holland in 1673 and measuring one-third inch by one-half inch, smaller than an ordinary postage stamp; John James Audubon’s elephant-folio Birds of America, published between 1827 and 1838, leaving its author to die impoverished, alone and insane; the companion volumes of Brobdingnagian and Lilliputian sizes of Gulliver’s Travels designed by Bruce Rogers for the Limited Editions Club of New York in 1950 — none of these has lasted except as a curiosity. But the essential shapes — those which allow readers to feel the physical weight of knowledge, the splendour of vast illustrations or the pleasure of being able to carry a book along on a walk or into bed — those remain.

A seventeenth-century Dutch woman portrayed by Bartholomeus van der Helst, holding an undersized volume in her right hand. (photo credit 9.17)

Books as visual puns: a 1950 edition of Gulliver’s Travels. (photo credit 9.18)

In the mid-1980s, an international group of North American archeologists excavating the huge Dakhleh Oasis in the Sahara found, in the corner of a single-storey addition to a fourth-century house, two complete books. One was an early manuscript of three political essays by the Athenian philosopher Isocrates; the other was a four-year record of the financial transactions of a local estate steward. This accounts book is the earliest complete example we have of a codex, or bound volume, and it is much like our paperbacks except for the fact that it is made not of paper but of wood. Each wooden leaf, five by thirteen inches and one-sixteenth inch thick, is bored with four holes on the left side, to be bound with a cord in eight-leaved signatures. Since the accounts book was used over a span of four years, it had to be “robust, portable, easy to use, and durable”.42 That anonymous reader’s requirements persist, with slight circumstantial variations, and agree with mine, sixteen vertiginous centuries later.

A mammoth page from Audubon’s Birds of America. (photo credit 9.19)

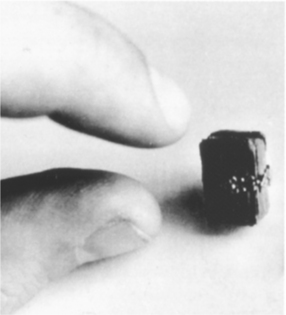

The world’s tiniest book, the seventeenth-century Enclosed Flower-Garden. (photo credit 9.20)

The “Sahara Penguin” discovered at the Dakhleh Oasis. (photo credit 9.21)

The eighteen-year-old Colette reading in the garden at Chatillon Coligny. (photo credit 9.22)