n March 26, 1892, Walt Whitman died in the house he had bought less than ten years before, in Camden, New Jersey — looking like an Old Testament king or, as Edmund Gosse described him, “a great old Angora Tom”. A picture taken a few years before his death, by the Philadelphia artist Thomas Eakins, shows him in his shaggy white mane, sitting by his window, thoughtfully watching the world outside, which was, he had told his readers, a gloss to his writing:

n March 26, 1892, Walt Whitman died in the house he had bought less than ten years before, in Camden, New Jersey — looking like an Old Testament king or, as Edmund Gosse described him, “a great old Angora Tom”. A picture taken a few years before his death, by the Philadelphia artist Thomas Eakins, shows him in his shaggy white mane, sitting by his window, thoughtfully watching the world outside, which was, he had told his readers, a gloss to his writing:

If you would understand me go to the heights or water-shore,

The nearest gnat is an explanation, and a drop or motion of waves a key,

The maul, the oar, the hand-saw, second my words.1

Whitman himself is there for the reader’s gaze. Two Whitmans, in fact: the Whitman in Leaves of Grass, “Walt Whitman, a kosmos, of Manhattan the son” but also born everywhere else (“I am of Adelaide … I am of Madrid … I belong in Moscow”);2 and the Whitman born on Long Island, who liked to read romances of adventure, and whose lovers were young men from the city, soldiers, bus drivers. Both became the Whitman who in his old age left his door open for visitors seeking “the sage of Camden”, and both had been offered to the reader, some thirty years earlier, in the 1860 edition of Leaves of Grass:

Who touches this, touches a man,

(Is it night? Are we here alone?)

It is I you hold, and who holds you,

I spring from the pages into your arms — decease calls me forth.3

Years later, in the “death-bed” edition of the often revised and augmented Leaves of Grass, the world does not “second” his words, but becomes the primordial voice; neither Whitman nor his verse mattered; the world itself sufficed, since it was nothing more or less than a book open for us all to read. In 1774, Goethe (whom Whitman read and admired) had written:

See how Nature is a living book,

Misunderstood but not beyond understanding.4

Now, in 1892, days before his death, Whitman agreed:

In every object, mountain, tree, and star — in every birth and life,

As part of each — evolv’d from each — meaning, behind the ostent,

A mystic cipher waits infolded.5

I read this for the first time in 1963, in a shaky Spanish version. One day in high school, a friend of mine who wanted to be a poet (we had just turned fifteen at the time) came running up to me with a book he had discovered, a blue-covered Austral edition of Whitman’s poems printed on rough, yellowed paper and translated by someone whose name I have forgotten. My friend was an admirer of Ezra Pound, whom he paid the compliment of imitating, and, since readers have no respect for the chronologies arduously established by well-paid academics, he thought Whitman was a poor imitation of Pound. Pound himself had tried to set the record straight, proposing “a pact” with Whitman:

It was you who broke the new wood,

Now is a time for carving.

We have one sap and one root —

Let there be commerce between us.6

But my friend would not be convinced. I accepted his verdict for the sake of friendship, and it wasn’t until a couple of years later that I came across a copy of Leaves of Grass in English and learned that Whitman had intended his book for me:

Thou reader throbbest life and pride and love the same as I,

Therefore for thee the following chants.7

I read Whitman’s biography, first in a series intended for the young which expurgated any reference to his sexuality and rendered him bland to the point of non-existence, and then in Geoffrey Dutton’s Walt Whitman, instructive but somewhat too sober. Years later, Philip Callow’s biography gave me a clearer picture of the man and allowed me to reconsider a couple of questions I had asked myself earlier: if Whitman had seen his reader as himself, who was this reader Whitman had in mind? And how had Whitman in turn become a reader?

Whitman learned to read in a Quaker school in Brooklyn, by what was known as the “Lancastrian method” (after the English Quaker Joseph Lancaster). A single teacher, helped by child monitors, was in charge of a class of some one hundred students, ten to a desk. The youngest were taught in the basement, the older girls on the ground floor and the older boys on the floor above. One of his teachers commented that he found him “a good-natured boy, clumsy and slovenly in appearance, but not otherwise remarkable”. The few textbooks were supplemented by the books his father, a fervent democrat who named his three sons after the founders of the United States, had at home. Many of these books were political tracts by Tom Paine, the socialist Frances Wright and the eighteenth-century French philosopher Constantin-François, Comte de Volney, but there were also collections of poetry and a few novels. His mother was illiterate but, according to Whitman, “excelled in narrative” and “had great mimetic powers”.8 Whitman first learned his letters from his father’s library; their sounds he learned from the stories he had heard his mother tell.

Whitman left school at eleven and entered the offices of the lawyer James B. Clark. Clark’s son, Edward, liked the bright boy and bought him a subscription to a circulating library. This, said Whitman later, “was the signal event of my life up to that time.” At the library he borrowed and read the Arabian Nights — “every single volume” — and the novels of Sir Walter Scott and James Fenimore Cooper. A few years afterwards, at the age of sixteen, he acquired “a stout, well-cramm’d one thousand page octavo volume … containing Walter Scott’s poetry entire” and this he avidly consumed. “Later, at intervals, summers and falls, I used to go off, sometimes for a week at a stretch, down in the country, or to Long Island’s seashores — there, in the presence of outdoor influences, I went over thoroughly the Old and New Testaments, and absorb’d (probably to greater advantage for me than in any library or indoor room — it makes such difference where you read) Shakespeare, Ossian, the best translated versions I could get of Homer, Aeschylus, Sophocles, the old German Nibelungen, the ancient Hindu poems, and one or two other masterpieces, Dante’s among them. As it happened, I read the latter mostly in an old wood.” And Whitman asks, “I have wonder’d since why I was not overwhelm’d by those mighty masters. Likely because I read them, as described, in the full presence of Nature, under the sun, with the far-spreading landscape and vistas, or the sea rolling in.”9 The place of reading, as Whitman suggests, is important, not only because it provides a physical setting for the text being read, but because it suggests, by juxtaposing itself with the place on the page, that both share the same hermeneutic quality, both tempting the reader with the challenge of elucidation.

Whitman didn’t stay long at the lawyer’s office; before the end of the year he had become an apprentice printer at the Long Island Patriot, learning to work a hand-press in a cramped basement under the supervision of the paper’s editor and author of all its articles. There Whitman learned of “the pleasing mystery of the different letters and their divisions — the great ‘e’ box — the box for spaces … the ‘a’ box, ‘I’ box, and all the rest,” the tools of his trade.

From 1836 to 1838 he worked as a country teacher in Norwich, New York. Payment was poor and erratic and, probably because school inspectors disapproved of his rowdy classrooms, he was forced to change schools eight times in those two years. His superiors cannot have been too pleased if he taught his students:

You shall no longer take things at second or third hand,

nor look through the eyes of the dead, nor feed on the spectres in books.10

He most honors my style who learns under it to destroy the teacher.11

After learning to print and teaching to read, Whitman found that he could combine both skills by becoming the editor of a paper: first the Long Islander, in Huntington, New York, and later the Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Here he began developing his notion of democracy as a society of “free readers”, untainted by fanaticism and political schools, whom the text-maker — poet, printer, teacher, newspaper editor — must serve empathically. “We really feel a desire to talk on many subjects,” he explained in an editorial on June 1, 1846, “to all the people of Brooklyn; and it ain’t their ninepences we want so much either. There is a curious kind of sympathy (haven’t you ever thought of it before?) that arises in the mind of a newspaper conductor with the public he serves.… Daily communion creates a sort of brotherhood and sisterhood between the two parties.”12

At about this time, Whitman came across the writings of Margaret Fuller. Fuller was an extraordinary personality: the first full-time book reviewer in the United States, the first female foreign correspondent, a lucid feminist, author of the impassioned tract Woman in the Nineteenth Century. Emerson thought that “all the art, the thought and nobleness in New England … seemed related to her, and she to it”.13 Hawthorne, however, called her “a great humbug”,14 and Oscar Wilde said that Venus had given her “everything except beauty” and Pallas “everything except wisdom”.15 While believing that books could not replace actual experience, Fuller saw in them “a medium for viewing all humanity, a core around which all knowledge, all experience, all science, all the ideal as well as all the practical in our nature could gather”. Whitman responded enthusiastically to her views. He wrote:

A passionate reader, Margaret Fuller. (photo credit 11.1)

Did we count great, O soul, to penetrate the themes of mighty books,

Absorbing deep and full from thoughts, plays, speculations?

But now from thee to me, caged bird, to feel thy joyous warble,

Filling the air, the lonesome room, the long forenoon,

Is it not just as great, O soul?16

For Whitman, text, author, reader and world mirrored each other in the act of reading, an act whose meaning he expanded until it served to define every vital human activity, as well as the universe in which it all took place. In this conjunction, the reader reflects the writer (he and I are one), the world echoes a book (God’s book, Nature’s book), the book is of flesh and blood (the writer’s own flesh and own blood, which through a literary transubstantiation become mine), the world is a book to be deciphered (the writer’s poems become my reading of the world). All his life, Whitman seems to have sought an understanding and a definition of the act of reading, which is both itself and the metaphor for all its parts.

“Metaphors,” wrote the German critic Hans Blumenberg, in our time, “are no longer considered first and foremost as representing the sphere that guides our hesitant theoretic conceptions, as an entrance hall to the forming of concepts, as a makeshift device within specialized languages that have not yet been consolidated, but rather as the authentic means to comprehend contexts.”17 To say that an author is a reader or a reader an author, to see a book as a human being or a human being as a book, to describe the world as text or a text as the world, are ways of naming the reader’s craft.

Such metaphors are very ancient ones, with roots in the earliest Judaeo-Christian society. The German critic E.R. Curtius, in a chapter on the symbolism of the book in his monumental European Literature and the Latin Middle Ages, suggested that book metaphors began in Classical Greece, but of these there are few examples, since Greek society, and later Roman society as well, did not consider the book an everyday object. Jewish, Christian and Islamic societies developed a profound symbolic relationship with their holy books, which were not symbols of God’s Word but God’s Word itself. According to Curtius, “the idea that the world and nature are books derives from the rhetoric of the Catholic Church, taken over by the mystical philosophers of the early Middle Ages, and finally become a commonplace.”

For the sixteenth-century Spanish mystic Fray Luis de Granada, if the world is a book, then the things of this world are the letters of the alphabet in which this book is written. In Introducción al símbolo de la fé (Introduction to the Symbol of Faith) he asked, “What are they to be, all the creatures of this world, so beautiful and so well crafted, but separated and illuminated letters that declare so rightly the delicacy and wisdom of their author? … And we as well … having been placed by you in front of this wonderful book of the entire universe, so that through its creatures, as if by means of living letters, we are to read the excellency of our Creator.”18

“The Finger of God,” wrote Sir Thomas Browne in Religio Medici, recasting Fray Luis’s metaphor, “hath left an Inscription upon all his works, not graphical or composed of Letters, but of their several forms, constitutions, parts and operations, which, aptly joyned together, do make one word that doth express their natures.”19 To this, centuries later, the Spanish-born American philosopher George Santayana added, “There are books in which the footnotes, or the comments scrawled by some reader’s hand in the margin, are more interesting than the text. The world is one of these books.”20

Our task, as Whitman pointed out, is to read the world, since that colossal book is the only source of knowledge for mortals. (Angels, according to Saint Augustine, don’t need to read the book of the world because they can see the Author Himself and receive from Him the Word in all its glory. Addressing himself to God, Saint Augustine reflects that angels “have no necessity to look upon the heavens or read them to read Your word. For they always see Your face, and there, without the syllables of time, they read Your eternal will. They read it, they choose it, they love it. They are always reading and what they read never comes to an end.… The book they read shall not be closed, the scroll shall not be rolled up again. For You are their book and You are eternal.”)21

Human beings, made in the image of God, are also books to be read. Here, the act of reading serves as a metaphor to help us understand our hesitant relationship with our body, the encounter and the touch and the deciphering of signs in another person. We read expressions on a face, we follow the gestures of a loved one as in an open book. “Your face, my Thane,” says Lady Macbeth to her husband, “is as a book where men may read strange matters,”22 and the seventeenth-century poet Henry King wrote of his young dead wife:

Dear Loss! since thy untimely fate

my task has been to meditate

On Thee, on Thee: Thou art the Book,

The Library whereon I look

Though almost blind.23

And Benjamin Franklin, a great book-lover, composed for himself an epitaph (unfortunately not used on his tombstone) in which the image of the reader as book finds its complete depiction:

The Body of

B. Franklin, Printer,

Like the cover of an old Book,

Its Contents torn out,

And stript of its Lettering & Gilding

Lies here, Food for Worms.

But the Work shall not be lost;

For it will, as he believ’d,

Appear once more

In a new and more elegant Edition

Corrected and improved

By the Author.24

To say that we read — the world, a book, the body — is not enough. The metaphor of reading solicits in turn another metaphor, demands to be explained in images that lie outside the reader’s library and yet within the reader’s body, so that the function of reading is associated with our other essential bodily functions. Reading — as we have seen — serves as a metaphoric vehicle, but in order to be understood must itself be recognized through metaphors. Just as writers speak of cooking up a story, rehashing a text, having half-baked ideas for a plot, spicing up a scene or garnishing the bare bones of an argument, turning the ingredients of a potboiler into soggy prose, a slice of life peppered with allusions into which readers can sink their teeth, we, the readers, speak of savouring a book, of finding nourishment in it, of devouring a book at one sitting, of regurgitating or spewing up a text, of ruminating on a passage, of rolling a poet’s words on the tongue, of feasting on poetry, of living on a diet of detective stories. In an essay on the art of studying, the sixteenth-century English scholar Francis Bacon catalogued the process: “Some books are to be tasted, others to be swallowed, and some few to be chewed and digested.”25

By extraordinary chance we know on what date this curious metaphor was first recorded.26 On July 31, 593 BC, by the river Chebar in the land of the Chaldeans, Ezekiel the priest had a vision of fire in which he saw “the likeness of the glory of the Lord” ordering him to speak to the rebellious children of Israel. “Open thy mouth, and eat what I give you,” the vision instructed him.

And when I looked, behold, an hand was sent unto me; and, lo, a roll of a book was therein;

And he spread it before me; and it was written within and without: and there was written therein lamentations, and mourning, and woe.27

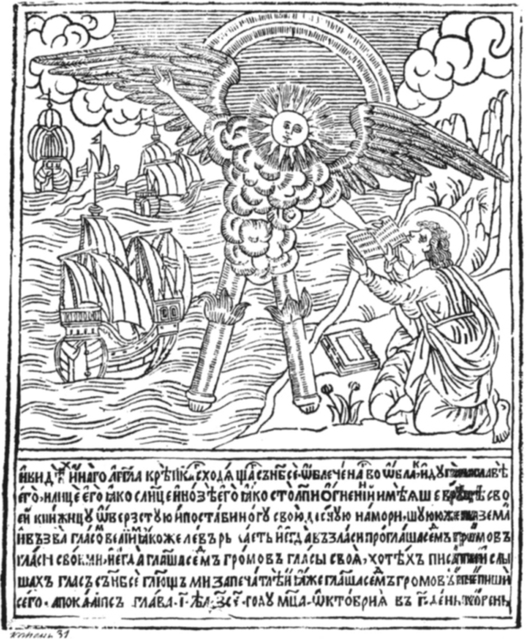

Saint John, recording his apocalyptic vision on Patmos, received the same revelation as Ezekiel. As he watched in terror, an angel came down from heaven with an open book, and a thundering voice told him not to write what he had learned, but to take the book from the angel’s hand.

And I went unto the angel, and said unto him. Give me the little book. And he said unto me, Take it, and eat it up; and it shall make thy belly bitter, but it shall be in thy mouth sweet as honey.

And I took the little book out of the angel’s hand, and ate it up; and it was in my mouth sweet as honey; and as soon as I had eaten it, my belly was bitter.

And he said unto me, Thou must prophesy again before many peoples, and nations, and tongues, and kings.28

Eventually, as reading developed and expanded, the gastronomic metaphor became common rhetoric. In Shakespeare’s time it was expected in literary parlance, and Queen Elizabeth I herself used it to describe her devotional reading: “I walke manie times into the pleasant fieldes of the Holye Scriptures, where I pluck up the goodlie greene herbes of sentences, eate them by reading, chewe them up musing, and laie them up at length in the seate of memorie … so I may the lesse perceive the bitterness of this miserable life.”29 By 1695 the metaphor had become so ingrained in the language that William Congreve was able to parody it in the opening scene of Love for Love, having the pedantic Valentine say to his valet, “Read, read, sirrah! and refine your appetite; learn to live upon instruction; feast your mind, and mortify your flesh; read, and take your nourishment in at your eyes; shut up your mouth, and chew the cud of understanding.” “You’ll grow devilish fat upon this paper diet,” is the valet’s comment.30

Saint John about to eat the Angel’s book, depicted in a seventeenth-century Russian broadside. (photo credit 11.2)

Less than a century later, Dr. Johnson read a book with the same manners he displayed at the table. He read, said Boswell, “ravenously, as if he devoured it, which was to all appearance his method of studying”. According to Boswell, Dr. Johnson kept a book wrapped in the tablecloth in his lap during dinner “from an avidity to have one entertainment in readiness, when he should have finished another; resembling (if I may use so coarse a simile) a dog who holds a bone in his paws in reserve, while he eats something else which has been thrown to him.”31

The ravenous reader, Dr. Johnson, by Sir Joshua Reynolds. (photo credit 11.3)

However readers make a book theirs, the end is that book and reader become one. The world that is a book is devoured by a reader who is a letter in the world’s text; thus a circular metaphor is created for the endlessness of reading. We are what we read. The process by which the circle is completed is not, Whitman argued, merely an intellectual one; we read intellectually on a superficial level, grasping certain meanings and conscious of certain facts, but at the same time, invisibly, unconsciously, text and reader become intertwined, creating new levels of meaning, so that every time we cause the text to yield something by ingesting it, simultaneously something else is born beneath it that we haven’t yet grasped. That is why — as Whitman believed, rewriting and re-editing his poems over and over again — no reading can ever be definitive. In 1867 he wrote, by way of explanation:

Shut not your doors to me proud libraries,

For that which was lacking on all your well-fill’d shelves, yet needed most, I bring

Forth from the war emerging, a book I have made,

The words of my book nothing, the drift of it every thing,

A book separate, not link’d with the rest nor felt by the intellect,

But you ye untold latencies will thrill to every page.32