n the summer of 1989, two years before the Gulf War, I travelled to Iraq to see the ruins of Babylon and the Tower of Babel. It was a journey I had long wanted to make. Reconstructed between 1899 and 1917 by the German archeologist Robert Koldewey,1 Babylon lies about forty miles south of Baghdad — a huge maze of butter-coloured walls that was once the most powerful city on earth, close to a clay mound which the guidebooks say is all that is left of the tower God cursed with multiculturalism. The taxi-driver who took me there knew the site only because it was near the town of Hillah, where he had once or twice gone to visit an aunt. I had brought with me a Penguin anthology of short stories, and after touring the ruins of what was for me, as a Western reader, the starting-place of every book, I sat down in the shade of an oleander bush and read.

n the summer of 1989, two years before the Gulf War, I travelled to Iraq to see the ruins of Babylon and the Tower of Babel. It was a journey I had long wanted to make. Reconstructed between 1899 and 1917 by the German archeologist Robert Koldewey,1 Babylon lies about forty miles south of Baghdad — a huge maze of butter-coloured walls that was once the most powerful city on earth, close to a clay mound which the guidebooks say is all that is left of the tower God cursed with multiculturalism. The taxi-driver who took me there knew the site only because it was near the town of Hillah, where he had once or twice gone to visit an aunt. I had brought with me a Penguin anthology of short stories, and after touring the ruins of what was for me, as a Western reader, the starting-place of every book, I sat down in the shade of an oleander bush and read.

Walls, oleander bushes, bituminous paving, open gateways, heaps of clay, broken towers: part of the secret of Babylon is that what the visitor sees is not one but many cities, successive in time but simultaneous in space. There is the Babylon of the Akkadian era, a small village of around 2350 BC. There is the Babylon where the epic of Gilgamesh, which includes one of the earliest accounts of Noah’s Flood, was recited for the first time, one day in the second millennium BC. There is the Babylon of King Hammurabi, of the eighteenth century BC, whose system of laws was one of the world’s first attempts at codifying the life of an entire society. There is the Babylon destroyed by the Assyrians in 689 BC. There is the rebuilt Babylon of Nebuchadnezzar, who around 586 BC besieged Jerusalem, sacked the Temple of Solomon and led the Jews into captivity, whereupon they sat by the rivers and wept. There is the Babylon of Nebuchadnezzar’s son or grandson (genealogists are undecided), King Belshazzar, who was the first man to see the writing on the wall, in the fearful calligraphy of God’s finger. There is the Babylon that Alexander the Great intended to be the capital of an empire extending from northern India to Egypt and Greece — the Babylon where the Conqueror of the World died at the age of thirty-three, in 323 BC, clutching a copy of the Iliad, back in the days when generals could read. There is Babylon the Great as conjured up by Saint John — the Mother of Harlots and Abominations of the Earth, the Babylon who made all nations drink of the wine of the wrath of her fornication. And then there is my taxi-driver’s Babylon, a place near the town of Hillah, where his aunt lived.

Here (or at least somewhere not too far from here), archeologists have argued, the prehistory of books began. Towards the middle of the fourth millennium BC, when the climate of the Near East became cooler and the air drier, the farming communities of southern Mesopotamia abandoned their scattered villages and regrouped within and around larger urban centres which soon became city-states.2 To maintain the scarce fertile lands they invented new irrigation techniques and extraordinary architectural devices, and to organize an increasingly complex society, with its laws and edicts and rules of commerce, towards the end of the fourth millennium the new urban dwellers developed an art that would change for ever the nature of communication between human beings: the art of writing.

In all probability, writing was invented for commercial reasons, to remember that a certain number of cattle belonged to a certain family, or were being transported to a certain place. A written sign served as a mnemonic device: a picture of an ox stood for an ox, to remind the reader that the transaction was in oxen, how many oxen, and perhaps the names of a buyer and seller. Memory, in this form, is also a document, the record of such a transaction.

The inventor of the first written tablets may have realized the advantage these pieces of clay had over the holding memory in the brain: first, the amount of information storable on tablets was endless — one could go on producing tablets ad infinitum, while the brain’s remembering capacity is limited; second, tablets did not require the presence of the memory-holder to retrieve information. Suddenly, something intangible — a number, an item of news, a thought, an order — could be acquired without the physical presence of the message-giver; magically, it could be imagined, noted and passed on across space and beyond time. Since the earliest vestiges of prehistoric civilization, human society had tried to overcome the obstacles of geography, the finality of death, the erosion of oblivion. With a single act — the incision of a figure on a clay tablet — that first anonymous writer suddenly succeeded in all these seemingly impossible feats.

But writing is not the only invention come to life in the instant of that first incision: one other creation took place at that same time. Because the purpose of the act of writing was that the text be rescued — that is to say, read — the incision simultaneously created a reader, a role that came into being before the actual first reader acquired a physical presence. As that first writer dreamed up a new art by making marks on a piece of clay, another art became tacitly apparent, one without which the markings would have been utterly meaningless. The writer was a maker of messages, the creator of signs, but these signs and messages required a magus who would decipher them, recognize their meaning, give them voice. Writing required a reader.

The primordial relationship between writer and reader presents a wonderful paradox: in creating the role of the reader, the writer also decrees the writer’s death, since in order for a text to be finished the writer must withdraw, cease to exist. While the writer remains present, the text remains incomplete. Only when the writer relinquishes the text, does the text come into existence. At that point, the existence of the text is a silent existence, silent until the moment in which a reader reads it. Only when the able eye makes contact with the markings on the tablet, does the text come to active life. All writing depends on the generosity of the reader.

This uneasy relationship between writer and reader has a beginning; it was established for all time on a mysterious Mesopotamian afternoon. It is a fruitful but anachronic relationship between a primeval creator who gives birth at the moment of death, and a post-mortem creator, or rather generations of post-mortem creators who enable the creation itself to speak, and without whom all writing is dead. From its very start, reading is writing’s apotheosis.

Writing was quickly recognized as a powerful skill, and through the ranks of Mesopotamian society rose the scribe. Obviously the skill of reading was also essential to him, but neither the name given to his occupation nor the social perception of his activities acknowledged the act of reading, and instead focused almost exclusively on his ability to record. Publicly, it was safer for the scribe to be seen not as one who retrieved information (and was thereby able to imbue it with sense) but as one who merely recorded it for the public good. Though he might be the eyes and tongue of a general, or even a king, such political power was better not flaunted. For this reason, the symbol of Nisaba, Mesopotamian goddess of scribes, was the stylus, not the tablet held before the eyes.

It would be hard to exaggerate the importance of the scribe’s role in Mesopotamian society. Scribes were needed to send messages, to convey news, to take down the king’s orders, to register the laws, to note the astronomical data necessary for keeping the calendar, to calculate the requisite number of soldiers or workers or supplies or head of cattle, to keep track of financial and economic transactions, to record medical diagnoses and prescriptions, to accompany military expeditions and write dispatches and chronicles of war, to assess taxes, to draw contracts, to preserve the sacred religious texts and to entertain the people with readings from the epic of Gilgamesh. None of this could be achieved without the scribe. He was the hand and eye and voice through which communications were established and messages deciphered. This is why the Mesopotamian authors addressed the scribe directly, knowing that the scribe would be the one to relay the message: “To My Lord, say this: thus speaks So-and-so, your servant”.3 “Say” addresses a second person, the “you”, earliest ancestor of the “Dear Reader” of later fiction. Each one of us, reading that line, becomes, across the ages, this “you”.

In the first half of the second millennium BC the priests of the temple of Shamash, in Sippar, in southern Mesopotamia, erected a monument covered with inscriptions on all twelve sides, dealing with the temple’s renovations and an increase in royal revenue. But instead of dating it in their own time, these primordial politicians dated it to the reign of King Manishtushu of Akkad (circa 2276–2261 BC), thereby establishing antiquity for the temple’s financial claims. The inscriptions end with the following promise to the reader: “This is not a lie, it is indeed the truth.”4 As the scribe-reader soon discovered, his art gave him the ability to modify the historical past.

With all the power that lay in their hands, the Mesopotamian scribes were an aristocratic elite. (Many years later, in the seventh and eighth centuries of the Christian era, the scribes of Ireland still benefited from this exalted status: the penalty for killing an Irish scribe was equal to that for killing a bishop.)5 In Babylon, only certain specially trained citizens could become scribes, and their function gave them pre-eminence over other members of their society. Textbooks (school tablets) have been discovered in most of the wealthier houses of Ur, from which it may be inferred that the arts of writing and reading were considered aristocratic activities. Those who were chosen to become scribes were taught, from a very early age, in a private school, an e-dubba or “tablet-house”. A room lined with clay benches in the palace of King Zimri-Lim of Mari,6 though it has yielded no school tablets to the scrutiny of archeologists, is considered to be a model for these schools for scribes.

The owner of the school, the headmaster or ummia, was assisted by an adda e-dubba or “father of the tablet-house” and an ugala or clerk. Several subjects were offered; for instance, in one of these schools a headmaster by the name of Igmil-Sin7 taught writing, religion, history and mathematics. Discipline was in the hands of an older student who fulfilled more or less the functions of a prefect. It was important for a scribe to do well at school, and there is evidence that fathers bribed the teachers to obtain good marks for their sons.

After learning the practical skills of fashioning clay tablets and handling the stylus, the student would have to learn how to draw and recognize the basic signs. By the second millennium BC, the Mesopotamian script had changed from pictographic — more or less accurate depictions of the objects for which the words stood — to what we know as “cuneiform” writing (from the Latin cuneus, “nail”), wedge-shaped signs representing sounds, not objects. The early pictograms (of which there were more than two thousand, as there was one sign for each represented object) had evolved into abstract markings that could represent not only the objects they depicted but also associated ideas; different words and syllables pronounced the same way were represented by the same sign. Auxiliary signs — phonetic or grammatical — led to an easier comprehension of the text and allowed for nuances of sense and shades of meaning. Within a short time, the system enabled the scribe to record a complex and highly sophisticated literature: epics, books of wisdom, humorous stories, love poems.8 Cuneiform writing, in fact, survived through the successive empires of Sumer, Akkadia and Assyria, recording the literature of fifteen different languages and covering an area occupied nowadays by Iraq, western Iran and Syria. Today we cannot read the pictographic tablets as a language because we don’t know the phonetic value of the early signs; we can only recognize a goat, a sheep. But linguists have tentatively reconstructed the pronunciation of the later Sumerian and Akkadian cuneiform texts, and we can, however rudimentarily, pronounce sounds coined thousands of years ago.

The first writing and reading skills were learned by practising the linking of signs, usually to form a name. There are numerous tablets that show these early, clumsy stages, with markings incised by an unsteady hand. The student had to learn to write following the conventions that would also allow him to read. For instance, the Akkadian word “to”, ana, had to be written a-na, not ana or an-a, so that the student would stress the syllables correctly.9

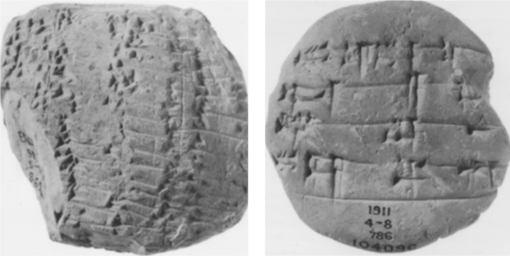

Once the student had mastered this stage, he would be given a different kind of clay tablet, a round one on which the teacher had inscribed a short sentence, proverb or list of names. The student would study the inscription, and then turn the tablet over and reproduce the writing. To do this, he would have to bear the words in his mind from one side of the tablet to the other, becoming for the first time a transmitter of messages — from reader of the teacher’s writing, to writer of that which he has read. In that small gesture a later function of the reader-scribe was born: copying a text, annotating it, glossing it, translating it, transforming it.

I speak of the Mesopotamian scribes as “he” since they were almost always male. Reading and writing were reserved for the power-holders in that patriarchal society. There are, however, exceptions. The earliest named author in history is a woman, Princess Enheduanna, born around 2300 BC, daughter of King Sargon I of Akkad, high priestess of the god of the moon, Nanna, and composer of a series of songs in honour of Inanna, goddess of love and war.10 Enheduanna signed her name at the end of her tablets. This was customary in Mesopotamia, and much of our knowledge of scribes comes from these signatures, or colophons, which included the name of the scribe, the date and the name of the town where the writing took place. This identification enabled the reader to read a text in a given voice — in the case of the hymns to Inanna, the voice of Enheduanna — identifying the “I” in the text with a specific person and thereby creating a pseudo-fictional character, “the author”, for the reader to engage with. This device, invented at the beginning of literature, is still with us more than four thousand years later.

The scribes must have been aware of the extraordinary power conferred by being the reader of a text, and guarded that prerogative jealously. Arrogantly, most Mesopotamian scribes would end their texts with this colophon: “Let the wise instruct the wise, for the ignorant may not see.”11 In Egypt during the nineteenth dynasty, around 1300 BC, a scribe composed this encomium of his trade:

Be a scribe! Engrave this in your heart

So that your name might live on like theirs!

The scroll is better than the carved stone.

A man has died: his corpse is dust,

And his people have passed from the land.

It is a book which makes him be remembered

In the mouth of the speaker who reads him.12

Two students’ tablets from Sumer. The teacher wrote on one side, the student copied the teacher’s writing on the other. (photo credit 12.1)

A writer can construct a text in any number of ways, choosing from the common stock of words those which seem to express the message best. But the reader receiving this text is not confined to any one interpretation. While, as we have said, the readings of a text are not infinite — they are circumscribed by conventions of grammar, and the limits imposed by common sense — they are not strictly dictated by the text itself. Any written text, says the French critic Jacques Derrida,13 “is readable even if the moment of its production is irrevocably lost and even if I don’t know what its alleged author consciously intended to say at the moment of writing it, i.e. abandoned the text to its essential drift.” For that reason, the author (the writer, the scribe) who wishes to preserve and impose a meaning must also be the reader. This is the secret privilege which the Mesopotamian scribe granted himself and which I, reading in the ruins that might have been his library, have usurped.

In a famous essay, Roland Barthes proposed a distinction between écrivain and écrivant: the former fulfils a function, the latter an activity; for the écrivain writing is an intransitive verb; for the écrivant the verb always leads to an objective — indoctrinating, witnessing, explaining, teaching.14 Possibly the same distinction can be made between two reading roles: that of the reader for whom the text justifies its existence in the act of reading itself, with no ulterior motive (not even entertainment, since the notion of pleasure is implied in the carrying out of the act), and that of the reader with an ulterior motive (learning, criticizing) for whom the text is a vehicle towards another function. The first activity takes place within a time frame dictated by the nature of the text; the second exists in a time frame imposed by the reader for the purpose of that reading. This may be what Saint Augustine believed was a distinction God Himself had established. “What My Scripture says, I say,” he hears God reveal to him. “But the Scripture speaks in time, whereas time does not affect My Word, which stands for ever, equal with Me in eternity. The things which you see by My Spirit, I see, just as I speak the words which you speak by My Spirit. But while you see those things in time, it is not in time that I see them. And while you speak those words in time, it is not in time that I speak them.”15

As the scribe knew, as society discovered, the extraordinary invention of the written word with all its messages, its laws, its lists, its literatures, depended on the scribe’s ability to restore the text, to read it. With that ability lost, the text becomes once again silent markings. The ancient Mesopotamians believed birds to be sacred because their footsteps on wet clay left marks that resembled cuneiform writing, and imagined that, if they could decipher the confusion of those signs, they would know what the gods were thinking. Generations of scholars have tried to become readers of scripts whose codes we have lost: Sumerian, Akkadian, Minoan, Aztec, Mayan.…

Sometimes they succeeded. Sometimes they failed, as in the case of Etruscan writing, whose intricacies we have not yet decoded. The poet Richard Wilbur summed up the tragedy that befalls a civilization when it loses its readers:

TO THE ETRUSCAN POETS

Dream fluently, still brothers, who when young

Took with your mothers’ milk the mother tongue,

In which pure matrix, joining world and mind,

You strove to leave some line of verse behind

Like a fresh track across a field of snow,

Not reckoning that all could melt and go.16

A fanciful map of Alexandria from a sixteenth-century manuscript. (photo credit 12.2)