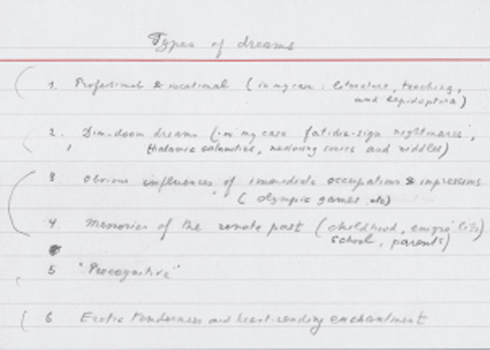

FIGURE 17. This card, listing “Types of Dreams,” appears among the dream records on a separate, undated card following the December 6, 1964, dream (most likely misplaced later).

FIGURE 17. This card, listing “Types of Dreams,” appears among the dream records on a separate, undated card following the December 6, 1964, dream (most likely misplaced later).

THE ADJECTIVE “DREAMY” (mechtatel’nyi, daydreaming, in Russian) is one of the most often used nuancers in Nabokov’s palette. In chapter 4 of the second part of Ada the nonagenarian Van Veen summarizes his dream life in what appears to be the closest we have got to a treatise of Nabokov’s dream theory and classification, influenced to a considerable degree by his 1964 experiment. It is worth giving here in its entirety, since Van’s examples match well the categories described here.

What are dreams? A random sequence of scenes, trivial or tragic, viatic or static, fantastic or familiar, featuring more or less plausible events patched up with grotesque details, and recasting dead people in new settings.

In reviewing the more or less memorable dreams I have had during the last nine decades I can classify them by subject matter into several categories among which two surpass the others in generic distinctiveness. There are the professional dreams and there are the erotic ones. In my twenties the first kind occurred about as frequently as the second, and both had their introductory counterparts, insomnias conditioned either by the overflow of ten hours of vocational work or by the memory of Ardis that a thorn in my day had maddeningly revived. After work I battled against the might of the mind-set: the stream of composition, the force of the phrase demanding to be formed could not be stopped for hours of darkness and discomfort, and when some result had been achieved, the current still hummed on and on behind the wall, even if I locked up my brain by an act of self-hypnosis (plain will, or pill, could no longer help) within some other image or meditation—but not Ardis, not Ada, for that would mean drowning in a cataract of worse wakefulness, with rage and regret, desire and despair sweeping me into an abyss where sheer physical extenuation stunned me at last with sleep.

In the professional dreams that especially obsessed me when I worked on my earliest fiction, and pleaded abjectly with a very frail muse (‘kneeling and wringing my hands’ like the dusty-trousered Marmlad before his Marmlady in Dickens), I might see for example that I was correcting galley proofs but that somehow (the great ‘somehow’ of dreams!) the book had already come out, had come out literally, being proffered to me by a human hand from the wastepaper basket in its perfect, and dreadfully imperfect, stage—with a typo on every page, such as the snide ‘bitterly’ instead of ‘butterfly’ and the meaningless ‘nuclear’ instead of ‘unclear.’ Or I would be hurrying to a reading I had to give—would feel exasperated by the sight of the traffic and people blocking my way, and then realize with sudden relief that all I had to do was to strike out the phrase ‘crowded street’ in my manuscript. What I might designate as ‘skyscape’ (not ‘skyscrape,’ as two-thirds of the class will probably take it down) dreams belongs to a subdivision of my vocational visions, or perhaps may represent a preface to them, for it was in my early pubescence that hardly a night would pass without some old or recent waketime impression’s establishing a soft deep link with my still-muted genius (for we are ‘van,’ rhyming with and indeed signifying ‘one’ in Marina’s double-you-less deep-voweled Russian pronunciation). The presence, or promise, of art in that kind of dream would come in the image of an overcast sky with a manifold lining of cloud, a motionless but hopeful white, a hopeless but gliding gray, showing artistic signs of clearing, and presently the glow of a pale sun grew through the leaner layer only to be recowled by the scud, for I was not yet ready.

Allied to the professional and vocational dreams are ‘dim-doom’ visions: fatidic-sign nightmares, thalamic calamities, menacing riddles. Not infrequently the menace is well concealed, and the innocent incident will turn out to possess, if jotted down and looked up later, the kind of precognitive flavor that Dunne has explained by the action of ‘reverse memory’; but for the moment I am not going to enlarge upon the uncanny element particular to dreams—beyond observing that some law of logic should fix the number of coincidences, in a given domain, after which they cease to be coincidences, and form, instead, the living organism of a new truth (‘Tell me,’ says Osberg’s little gitana to the Moors, El Motela and Ramera, ‘what is the precise minimum of hairs on a body that allows one to call it “hairy”’?).

Between the dim-doom and the poignantly sensual, I would place ‘melts’ of erotic tenderness and heart-rending enchantment, chance frôlements of anonymous girls at vague parties, half-smiles of appeal or submission—forerunners or echoes of the agonizing dreams of regret when series of receding Adas faded away in silent reproach; and tears, even hotter than those I would shed in waking life, shook and scalded poor Van, and were remembered at odd moments for days and weeks.

Van’s sexual dreams are embarrassing to describe in a family chronicle that the very young may perhaps read after a very old man’s death. Two samples, more or less euphemistically worded, should suffice. In an intricate arrangement of thematic recollections and automatic phantasmata, Aqua impersonating Marina or Marina made-up to look like Aqua, arrives to inform Van, joyfully, that Ada has just been delivered of a girl-child whom he is about to know carnally on a hard garden bench while under a nearby pine, his father, or his dress-coated mother, is trying to make a transatlantic call for an ambulance to be sent from Vence at once. Another dream, recurring in its basic, unmentionable form, since 1888 and well into this century, contained an essentially triple and, in a way, tribadic, idea. Bad Ada and lewd Lucette had found a ripe, very ripe ear of Indian corn. Ada held it at both ends as if it were a mouth organ and now it was an organ, and she moved her parted lips along it, varnishing its shaft, and while she was making it trill and moan, Lucette’s mouth engulfed its extremity. The two sisters’ avid lovely young faces were now close together, doleful and wistful in their slow, almost languid play, their tongues meeting in flicks of fire and curling back again, their tumbled hair, red-bronze and black-bronze, delightfully commingling and their sleek hindquarters lifted high as they slaked their thirst in the pool of his blood.

I have some notes here on the general character of dreams. One puzzling feature is the multitude of perfect strangers with clear features, but never seen again, accompanying, meeting, welcoming me, pestering me with long tedious tales about other strangers—all this in localities familiar to me and in the midst of people, deceased or living, whom I knew well; or the curious tricks of an agent of Chronos—a very exact clock-time awareness, with all the pangs (possibly full-bladder pangs in disguise) of not getting somewhere in time, and with that clock hand before me, numerically meaningful, mechanically plausible, but combined—and that is the curious part—with an extremely hazy, hardly existing passing-of-time feeling (this theme I will also reserve for a later chapter). All dreams are affected by the experiences and impressions of the present as well as by memories of childhood; all reflect, in images or sensations, a draft, a light, a rich meal or a grave internal disorder. Perhaps the most typical trait of practically all dreams, unimportant or portentous—and this despite the presence, in stretches or patches, of fairly logical (within special limits) cogitation and awareness (often absurd) of dream-past events—should be understood by my students as a dismal weakening of the intellectual faculties of the dreamer, who is not really shocked to run into a long-dead friend. At his best the dreamer wears semi-opaque blinkers; at his worst he’s an imbecile. The class (1891, 1892, 1893, 1894, et cetera) will carefully note (rustle of bluebooks) that, owing to their very nature, to that mental mediocrity and bumble, dreams cannot yield any semblance of morality or symbol or allegory or Greek myth, unless, naturally, the dreamer is a Greek or a mythicist. Metamorphoses in dreams are as common as metaphors in poetry. A writer who likens, say, the fact of imagination’s weakening less rapidly than memory, to the lead of a pencil getting used up more slowly than its erasing end, is comparing two real, concrete, existing things. Do you want me to repeat that? (cries of ‘yes! yes!’) Well, the pencil I’m holding is still conveniently long though it has served me a lot, but its rubber cap is practically erased by the very action it has been performing too many times. My imagination is still strong and serviceable but my memory is getting shorter and shorter. I compare that real experience to the condition of this real commonplace object. Neither is a symbol of the other. Similarly, when a teashop humorist says that a little conical titbit with a comical cherry on top resembles this or that (titters in the audience) he is turning a pink cake into a pink breast (tempestuous laughter) in a fraise-like frill or frilled phrase (silence). Both objects are real, they are not interchangeable, not tokens of something else, say, of Walter Raleigh’s decapitated trunk still topped by the image of his wetnurse (one lone chuckle). Now the mistake—the lewd, ludicrous and vulgar mistake of the Signy-Mondieu analysts consists in their regarding a real object, a pompon, say, or a pumpkin (actually seen in a dream by the patient) as a significant abstraction of the real object, as a bumpkin’s bonbon or one-half of the bust if you see what I mean (scattered giggles). There can be no emblem or parable in a village idiot’s hallucinations or in last night’s dream of any of us in this hall. In those random visions nothing—underscore ‘nothing’ (grating sound of horizontal strokes)—can be construed as allowing itself to be deciphered by a witch doctor who can then cure a madman or give comfort to a killer by laying the blame on a too fond, too fiendish or too indifferent parent—secret festerings that the foster quack feigns to heal by expensive confession fests (laughter and applause).1

In an introductory note to his experiment, Nabokov subdivides his usual dreams thematically into six rough types (see the list on page 34). Yet even the dreams he sees during the experiment do not fit these six categories neatly. Is jumping into a ditch during shooting in an unknown town (#36) a fatidic dream? Can seeing Edmund Wilson making, in a “Lausanne-like railway station,” a critical comment of Nabokov’s would-be peculiarly “Russian” usage of the word “upstairs” (#46), half-a-year prior to their famous public falling-out over Wilson’s feeble but presumptive command of Russian, be a precognitive dream? Or simply associative with Wilson’s To the Finland Station, published in 1940, the year when Nabokov first met him and politely dismissed Wilson’s left-wing political naïveté on display in that book? Is every “erotic” dream of his so tender and enchanting (e.g., #IV)? Can he know a “precognitive” dream when he sees one (the point of Dunne’s experiment, of course)?

I therefore had to add a few new type-models in this section and some variations into Nabokov’s. For example, it seems inadequate to label dreams visited by his father (#38, or 25 Jan. 1951, #III) as mere “memories of the remote past”: his father appears in a faintly unfamiliar guise, unsmiling, remote, even morose, as though his present mysterious after-death condition made the change of attitude inevitable, painful as it may be for his son. And when Nabokov’s characters dream of their fathers, they often experience a similar sensation of awe, enigma, and dread, nowhere staged as masterfully and vividly as in the tremendous passage from The Gift, given here in full.

A subspecies within each type is named in brackets. It is often difficult to place a passage under a thematic rubric: it may straddle more than one or even two, or, conversely, it may require for itself a subtler subsection. In fiction, Nabokov staged his characters’ dreams, composing them from the pieces of his own dreaming experience (memory) and those custom-made for the occasion (imagination). Within a given category, dreams culled from fiction are ordered by ascending chronology.

The original Russian text important to the thematic section, but left out in translation by oversight or on purpose, is inserted in angle brackets (in my rendition); important additions made in an English version are italicized.

The excerpts below do not include examples from Nabokov’s plays. Most of them are conceived and set as Calderonic dreams. In the early masterpiece The Tragedy of Mr. Morn (1924), the curtain rises on a character slumbering in an armchair, whose first words upon waking up are “Dream, fever, dream . . .”; indeed, the entire drama turns out to be a dream of a “foreign author” who visits the scene of his fantasy. The late The Event (1938) leaves a like suspicion that either the play is a dream or else life is, since the two protagonists are given sometimes to see an “exit” sign dimly lit outside of their nightmare. And in his last play, The Waltz Invention, the chief dramatic persona is a sleeping persona; in fact, “Dream” (renamed “Trance” in translation) is the most important actor and stage director.

Dreams related to the writer’s craft, particularly verbal manipulation

He resembled somewhat Bouteillan as the latter had been ten years ago and as he had appeared in a dream, which Van now retrostructed as far as it would go: in it Demon’s former valet explained to Van that the ‘dor’ in the name of an adored river equaled the corruption of hydro in ‘dorophone.’ Van often had word dreams. (Ada, 309)

Somebody said, wheeling a table nearby: “It’s one of the Vane sisters,” and he awoke murmuring with professional appreciation the oneiric word-play combining his name and surname, and plucked out the wax plugs. (Ada, 521)

Dreams displaying supposed signs of impending disaster, especially death

He came to in the middle of the room, awakened by a sense of unbearable horror. The horror had knocked him off the bed. He had dreamt that the wall next to which stood his bed had begun slowly collapsing onto him—so he had recoiled with a spasmodic exhalation. (“Wingstroke,” Stories, 32)

Recently, in her sleep, she had had a vision of a dead youth with whom, before she was married, she had strolled in the twilight, when the blackberry blooms seem so ghostly white. Next morning, still as if half-asleep, she had penciled a letter to him—a letter to her dream. In this letter she had lied to poor Jack. She had, in fact, nearly forgotten about him; she loved her excruciating husband with a fearful but faithful love; yet she wanted to send a little warmth to this dear spectral visitor, to reassure him with some words from earth. The letter vanished mysteriously from her writing pad, and the same night she dreamt of a long table, from under which Jack suddenly emerged, nodding to her gratefully. . . . Now, for some reason, she felt uneasy when recalling that dream . . . As if she had cheated on her husband with a ghost . . . (“Revenge,” Stories, 70)

And once he dreamt he saw Turati sitting with his back to him. Turati was deep in thought, leaning on one arm, but from behind his broad back it was impossible to see what it was he was bending over and pondering. Luzhin did not want to see what it was, afraid to see, but nonetheless he cautiously began to look over the black shoulder. And then he saw that a bowl of soup stood before Turati and that he was not leaning on his arm but was merely tucking a napkin into his collar. And on the November day which this dream preceded Luzhin was married. (The Defense, 177)

Sleep imperceptibly took advantage of this happiness and relief but now, in sleep, there was no rest at all, for sleep consisted of sixty-four squares, a gigantic board in the middle of which, trembling and stark-naked, Luzhin stood, the size of a pawn, and peered at the dim positions of huge pieces, <humpbacked>, megacephalous, with crowns or manes. (The Defense, 236)

Sometimes in his dreams he swore to the doctor with the agate eyes that he was not playing chess—he had merely set out the pieces once on a pocket board and glanced at two or three games printed in the newspapers—simply for lack of something to do. (The Defense, 241–42)

False Predictors

She believed in dreams: to dream you had lost a tooth portended the death of someone you knew; and if there came blood with the tooth, then it would be the death of a relative. A field of daisies foretold meeting again one’s first lover. Pearls stood for tears. It was very bad to see oneself all in white sitting at the head of the table. Mud meant money; a cat—treason; the sea-trouble for the soul. She was fond of recounting her dreams, circumstantially and at length. (Despair, 32)

Recurrent

For several years I was haunted by a very singular and very nasty dream: I dreamed I was standing in the middle of a long passage with a door at the bottom, and passionately wanting, but not daring to go and open it, and then deciding at last to go, which I accordingly did; but at once awoke with a groan, for what I saw there was unimaginably terrible; to wit, a perfectly empty, newly whitewashed room. That was all, but it was so terrible that I never could hold out; then one night a chair and its slender shadow appeared in the middle of the bare room—not as a first item of furniture but as though somebody had brought it to climb upon it and fix a bit of drapery, and since I knew whom I would find there next time stretching up with a hammer and a mouthful of nails, I spat them out and never opened that door again. (Despair, 56–57)

. . . instead of writing I went out of doors again, roaming till late, and when I returned, I was so utterly fagged out, that sleep overcame me at once, despite the confused discomfort of my mind. I dreamt that after a tedious search (offstage—not shown in my dream) I at last found Lydia, who was hiding from me and who now coolly declared that all was well, she had got the inheritance all right and was going to marry another man, “because, you see,” she said, “you are dead.” I woke up in a terrific rage, my heart pounding madly: fooled! helpless!—for how could a dead man sue the living—yes, helpless—and she knew it! Then I came to my wits again and laughed—what humbugs dreams are liable to be. (Despair, 209–210)

Message Unrecognized

Atavistic peace came with dawn, and when I slipped into sleep the sun through the tawny window shades penetrated a dream that somehow was full of Cynthia.

This was disappointing. Secure in the fortress of daylight, I said to myself that I had expected more. She, a painter of glass-bright minutiae—and now so vague! I lay in bed, thinking my dream over and listening to the sparrows outside: Who knows, if recorded and then run backward, those bird sounds might not become human speech, voiced words, just as the latter become a twitter when reversed? I set myself to reread my dream—backward, diagonally, up, down—trying hard to unravel something Cynthia-like in it, something strange and suggestive that must be there.

I could isolate, consciously, little. Everything seemed blurred, yellow-clouded, yielding nothing tangible. Her inept acrostics, maudlin evasions, theopathies—every recollection formed ripples of mysterious meaning. Everything seemed yellowly blurred, illusive, lost. (“The Vane Sisters,” Stories, 631)

When I was a boy of seven or eight, I used to dream a vaguely recurrent dream set in a certain environment, which I have never been able to recognize and identify in any rational manner, though I have seen many strange lands. I am inclined to make it serve now, in order to patch up a gaping hole, a raw wound in my story. There was nothing spectacular about that environment, nothing monstrous or even odd: just a bit of noncommittal stability represented by a bit of level ground and filmed over with a bit of neutral nebulosity; in other words, the indifferent back of a view rather than its face. The nuisance of that dream was that for some reason I could not walk around the view to meet it on equal terms. There lurked in the mist a mass of something—mineral matter or the like—oppressively and quite meaninglessly shaped, and, in the course of my dream, I kept filling some kind of receptacle (translated as “pail”) with smaller shapes (translated as “pebbles”), and my nose was bleeding but I was too impatient and excited to do anything about it. And every time I had that dream, suddenly somebody would start screaming behind me, and I awoke screaming too, thus prolonging the initial anonymous shriek, with its initial note of rising exultation, but with no meaning attached to it any more—if there had been a meaning. Speaking of Lance, I would like to submit that something on the lines of my dream— But the funny thing is that as I reread what I have set down, its background, the factual memory vanishes—has vanished altogether by now—and I have no means of proving to myself that there is any personal experience behind its description. What I wanted to say was that perhaps Lance and his companions, when they reached their planet, felt something akin to my dream—which is no longer mine. (“Lance,” Stories, 640–41)

And that night I dreamt a singularly unpleasant dream. I dreamt I was sitting in a large dim room which my dream had hastily furnished with odds and ends collected in different houses I vaguely knew, but with gaps or strange substitutions, as for instance that shelf which was at the same time a dusty road. I had a hazy feeling that the room was in a farmhouse or a country inn—a general impression of wooden walls and planking. We were expecting Sebastian—he was due to come back from some long journey. I was sitting on a crate or something, and my mother was also in the room, and there were two more persons drinking tea at the table round which we were seated—a man from my office and his wife, both of whom Sebastian had never known, and who had been placed there by the dream manager—just because anybody would do to fill the stage.

Our wait was uneasy, laden with obscure forebodings, and I felt that they knew more than I, but I dreaded to inquire why my mother worried so much about a muddy bicycle which refused to be crammed into the wardrobe: its doors kept opening. There was the picture of a steamer on the wall, and the waves on the picture moved like a procession of caterpillars, and the steamer rocked and this annoyed me—until I remembered that the hanging of such a picture was an old and commonplace custom, when awaiting a traveller’s return. He might arrive at any moment, and the wooden floor near the door had been sprinkled with sand, so that he might not slip. My mother wandered away with the muddy spurs and stirrups she could not hide, and the vague couple was quietly abolished, for I was alone in the room, when a door opened in a gallery upstairs, and Sebastian appeared, slowly descending a rickety flight of stairs which came straight down into the room. His hair was tousled and he was coatless: he had, I understood, just been taking a nap after his journey. As he came down, pausing a little on every step, with always the same foot ready to continue and with his arm resting on the wooden handrail, my mother came back again and helped him to get up when he stumbled and slithered down on his back. He laughed as he came up to me, but I felt that he was ashamed of something. His face was pale and unshaven, but it looked fairly cheerful. My mother, with a silver cup in her hand, sat down on what proved to be a stretcher, for she was presently carried away by two men who slept on Saturdays in the house, as Sebastian told me with a smile. Suddenly I noticed that he wore a black glove on his left hand, and that the fingers of that hand did not move, and that he never used it—I was afraid horribly, squeamishly, to the point of nausea, that he might inadvertently touch me with it, for I understood now that it was a sham thing attached to the wrist—that he had been operated upon, or had had some dreadful accident. I understood too why his appearance and the whole atmosphere of his arrival seemed so uncanny, but though he perhaps noticed my shudder, he went on with his tea. My mother came back for a moment to fetch the thimble she had forgotten and quickly went away, for the men were in a hurry. Sebastian asked me whether the manicurist had already come, as he was anxious to get ready for the banquet. I tried to dismiss the subject, because the idea of his maimed hand was insufferable, but presently I saw the whole room in terms of jagged fingernails, and a girl I had known (but she had strangely faded now) arrived with her manicure case and sat down on a stool in front of Sebastian. He asked me not to look, but I could not help looking. I saw him undoing his black glove and slowly pulling it off; and as it came off, it spilled its only contents—a number of tiny hands, like the front paws of a mouse, mauve-pink and soft—lots of them—and they dropped to the floor, and the girl in black went on her knees. I bent down to see what she was doing under the table and I saw that she was picking up the little hands and putting them into a dish—I looked up and Sebastian had vanished, and when I bent down again, the girl had vanished too. I felt I could not stay in that room for a moment longer. But as I turned and groped for the latch I heard Sebastian’s voice behind me; it seemed to come from the darkest and remotest corner of what was now an enormous barn with grain trickling out of a punctured bag at my feet. I could not see him and was so eager to escape that the throbbing of my impatience seemed to drown the words he said. I knew he was calling me and saying something very important—and promising to tell me something more important still, if only I came to the corner where he sat or lay, trapped by the heavy sacks that had fallen across his legs. I moved, and then his voice came in one last loud insistent appeal, and a phrase which made no sense when I brought it out of my dream, then, in the dream itself, rang out laden with such absolute moment, with such an unfailing intent to solve for me a monstrous riddle, that I would have run to Sebastian after all, had I not been half out of my dream already. (The Real Life of Sebastian Knight, 187–90)

It bristled with farcical anachronisms; it was suffused with a sense of gross maturity (as in Hamlet the churchyard scene); its somewhat meagre setting was patched up with odds and ends from other (later) plays; but still the recurrent dream we all know (finding ourselves in the old classroom, with our homework not done because of our having unwittingly missed ten thousand days of school) was in Krug’s case a fair rendering of the atmosphere of the original version. Naturally, the script of daytime memory is far more subtle in regard to factual details, since a good deal of cutting and trimming and conventional recombination has to be done by the dream producers (of whom there are usually several, mostly illiterate and middle-class and pressed by time); but a show is always a show, and the embarrassing return to one’s former existence (with the off-stage passing of years translated in terms of forgetfulness, truancy, inefficiency) is somehow better enacted by a popular dream than by the scholarly precision of memory. < . . . > But among the producers or stagehands responsible for the setting there has been one . . . it is hard to express it . . . a nameless, mysterious genius who took advantage of the dream to convey his own peculiar code message which has nothing to do with school days or indeed with any aspect of Krug’s physical existence, but which links him up somehow with an unfathomable mode of being, perhaps terrible, perhaps blissful, perhaps neither, a kind of transcendental madness which lurks behind the corner of consciousness and which cannot be defined more accurately than this, no matter how Krug strains his brain. (Bend Sinister, 55–56)

In the middle of the night something in a dream shook him out of his sleep into what was really a prison cell with bars of light (and a separate pale gleam like the footprint of some phosphorescent islander) breaking the darkness. At first, as sometimes happens, his surroundings did not match any form of reality. Although of humble origin (a vigilant arc light outside, a livid corner of the prison yard, an oblique ray coming through some chink or bullet hole in the bolted and padlocked shutters) the luminous pattern he saw assumed a strange, perhaps fatal significance, the key to which was half-hidden by a flap of dark consciousness on the glimmering floor of a half-remembered nightmare. It would seem that some promise had been broken, some design thwarted, some opportunity missed—or so grossly exploited as to leave an afterglow of sin and shame. The pattern of light was somehow the result of a kind of stealthy, abstractly vindictive, groping, tampering movement that had been going on in a dream, or behind a dream, in a tangle of immemorial and by now formless and aimless machinations. Imagine a sign that warns you of an explosion in such cryptic or childish language that you wonder whether everything—the sign, the frozen explosion under the window sill and your quivering soul—has not been reproduced artificially, there and then, by special arrangement with the mind behind the mirror.

It was at that moment, just after Krug had fallen through the bottom of a confused dream and sat up on the straw with a gasp—and just before his reality, his remembered hideous misfortune could pounce upon him—it was then that I felt a pang of pity for Adam and slid towards him along an inclined beam of pale light—causing instantaneous madness, but at least saving him from the senseless agony of his logical fate. (Bend Sinister, 209–10)

For as we know from dreams it is so hard

To speak to our dear dead! They disregard

Our apprehension, queasiness and shame—

The awful sense that they’re not quite the same.

And our school chum killed in a distant war

Is not surprised to see us at his door.

And in a blend of jauntiness and gloom

Points at the puddles in his basement room.

(“Pale Fire,” ll. 589–96, Pale Fire)

[Hugh Person dozes off as the fire is creeping up to his hotel floor.] Here comes the air hostess bringing bright drinks, and she is Armande who has just accepted his offer of marriage though he warned her that she overestimated a lot of things, the pleasures of parties in New York, the importance of his job, a future inheritance, his uncle’s stationery business, the mountains of Vermont—and now the airplane explodes with a roar and a retching cough. < . . . > Coughing, our Person sat up in asphyxiating darkness and groped for the light. (Transparent Things, 103)

At its worst it went like this: An hour or so after falling asleep (generally well after midnight and with the humble assistance of a little Old Mead or Chartreuse) I would wake up (or rather “wake in”) momentarily mad. The hideous pang in my brain was triggered by some hint of faint light in the line of my sight, for no matter how carefully I might have topped the well-meaning efforts of a servant by my own struggles with blinds and purblinds, there always remained some damned slit, some atom or dimmet of artificial streetlight or natural moonlight that signaled inexpressible peril when I raised my head with a gasp above the level of a choking dream. Along the dim slit brighter points traveled with dreadful meaningful intervals between them. Those dots corresponded, perhaps, to my rapid heartbeats or were connected optically with the blinking of wet eyelashes but the rationale of it is inessential; its dreadful part was my realizing in helpless panic that the event had been stupidly unforeseen, yet had been bound to happen and was the representation of a fatidic problem which had to be solved lest I perish and indeed might have been solved now if I had given it some forethought or had been less sleepy and weak-witted at this all-important moment. The problem itself was of a calculatory order: certain relations between the twinkling points had to be measured or, in my case, guessed, since my torpor prevented me from counting them properly, let alone recalling what the safe number should be. Error meant instant retribution—beheading by a giant or worse; the right guess, per contra, would allow me to escape into an enchanting region situated just beyond the gap I had to wriggle through in the thorny riddle, a region resembling in its idyllic abstraction those little landscapes engraved as suggestive vignettes—a brook, a bosquet—next to capital letters of weird, ferocious shape such as a Gothic B beginning a chapter in old books for easily frightened children. But how could I know in my torpor and panic that this was the simple solution, that the brook and the boughs and the beauty of the Beyond all began with the initial of Being? < . . . > There were nights, of course, when my reason returned at once and I rearranged the curtains and presently slept. (Look at the Harlequins! 15)

(An effect opposite to one in his childhood, when VN dreaded to be left at night in complete darkness, hoping for a chink of light from under the door to be let stay—cf. pp. 108–9)

(An effect opposite to one in his childhood, when VN dreaded to be left at night in complete darkness, hoping for a chink of light from under the door to be let stay—cf. pp. 108–9)

In a recurrent dream of my childhood I used to see a smudge on the wallpaper or on a whitewashed door, a nasty smudge that started to come alive, turning into a crustacean-like monster. As its appendages began to move, a thrill of foolish horror shook me awake; but the same night or the next I would be again facing idly some wall or screen on which a spot of dirt would attract the naive sleeper’s attention by starting to grow and make groping and clasping gestures—and again I managed to wake up before its bloated bulk got unstuck from the wall. But one night when some trick of position, some dimple of pillow, some fold of bedclothes made me feel brighter and braver than usual, I let the smudge start its evolution and, drawing on an imagined mitten, I simply rubbed out the beast. Three or four times it appeared again in my dreams but now I welcomed its growing shape and gleefully erased it. Finally it gave up—as some day life will give up—bothering me. (The Original of Laura, 249–53)

Humdrum images or events of the day that acquire significance in the subsequent dream, disfigured or fantastically rearranged.

The Staircase was the main idol of her [Margot’s] existence—not as a symbol of glorious ascension, but as a thing to be kept nicely polished, so that her worst nightmare (after too generous a helping of potatoes and sauerkraut) was a flight of white steps with the black trace of a boot first right, then left, then right again and so on—up to the top landing. (Laughter in the Dark, 24–25)

The original Russian version:

<In her night dreams, she [Magda] often saw a fabulously splendid, white-as-sugar staircase and a tiny silhouette of a man who had already reached the top but left a large black imprint of his sole on every step, left-right-left-right. . . . It was a painful dream.> (Camera Obscura, 16)

In that book all three major characters have their dreams reported.

In that book all three major characters have their dreams reported.

Van managed to sleep soundly, the only reaction on the part of his dormant mind being the dream image of an aquatic peacock, slowly sinking before somersaulting like a diving grebe, near the shore of the lake bearing his name in the ancient kingdom of Arrowroot. Upon reviewing that bright dream he traced its source to his recent visit to Armenia where he had gone fowling with Armborough and that gentleman’s extremely compliant and accomplished niece. He wanted to make a note of it—and was amused to find that all three pencils had not only left his bed table but had neatly aligned themselves head to tail along the bottom of the outer door of the adjacent room, having covered quite a stretch of blue carpeting in the course of their stopped escape. (Ada, 474–75)

Then [Klara] fell asleep and had a nonsensical dream: she seemed to be sitting in a tramcar next to an old woman extraordinarily like her Lodz aunt, who was talking rapidly in German; then it gradually turned out that it was not her aunt at all but the cheerful marketwoman from whom Klara bought oranges on her way to work. (Mary, 37)

[“Although an ass might argue that ‘orange’ is the oneiric anagram of organe, I would not advise members of the Viennese delegation to lose precious time analyzing Klara’s dream at the end of Chapter Four in the present book.” (VN’s preface, Mary, xiii)]

He returned to his squalid hotel and, slowly stretching his intertwined hands behind his head, collapsed onto the bed in a state of blissful solar inebriation. He dreamt he was an officer again, walking along a Crimean slope overgrown with milkweed and oak shrubs, mowing off the downy heads of thistles as he went. He awoke because he had started laughing in his sleep; he awoke, and the window had already turned a twilight blue. (“The Seaport,” Stories, 64)

(see also Insomnia, Clairvoyance, and Life Is a Dream)

His heart was thumping rapidly because he sensed that Maureen had entered his room. Just now, in his momentary dream, he had been talking to her, helping her climb the waxen path between black cliffs with their occasional glossy, oil-paint fissures. Now and then a dulcet breeze made the narrow white headdress quiver gently, like a sheet of thin paper, on her dark hair. (“La Veneziana,” Stories, 108)

This is an example of an almost perfect “Dunne’s Dream”: what he saw in that instantaneous dream (“he had just fallen asleep and, as sometimes happens, the very act of falling asleep was what woke him”) is soon to come true in reality retrospectively, as it were—a fantastic reality, to be sure, but then that is what fiction is all about.

This is an example of an almost perfect “Dunne’s Dream”: what he saw in that instantaneous dream (“he had just fallen asleep and, as sometimes happens, the very act of falling asleep was what woke him”) is soon to come true in reality retrospectively, as it were—a fantastic reality, to be sure, but then that is what fiction is all about.

To begin with, I slept badly for three nights in a row and did not sleep at all during the fourth. In recent years I had lost the habit of solitude, and now those solitary nights caused me acute unrelieved anguish. The first night I saw my girl in dream: sunlight flooded her room, and she sat on the bed wearing only a lacy nightgown, and laughed, and laughed, could not stop laughing. And I recalled my dream quite by accident, as I was passing a lingerie store, and upon remembering it realized that all that had been so gay in my dream—her lace, her thrown-back head, her laughter—was now, in my waking state, frightening. Yet I could not explain to myself why that lacy laughing dream was now so unpleasant, so hideous. (“Terror,” Stories, 176)

Gradually Graf dozed off in his chair and in his dream he saw Ivan Ivanovich Engel singing couplets in a garden of sorts and fanning his bright-yellow, curly-feathered wings, and when Graf woke up the lovely June sun was lighting little rainbows in the landlady’s liqueur glasses, and everything was somehow soft and luminous and enigmatic—as if there was something he had not understood, not thought through to the end, and now it was already too late, another life had begun, the past had withered away, and death had quite, quite removed the meaningless memory, summoned by chance from the distant and humble home where it had been living out its obscure existence. (“A Busy Man,” Stories, 295–96)

The chambermaid did not have to wake Luzhin—he awoke by himself and immediately made strenuous efforts to recall the delightful dream he had dreamed, knowing from experience that if you didn’t begin immediately to recall it, later would be too late. He had dreamed he was sitting strangely—in the middle of the room—and suddenly, with the absurd and blissful suddenness usual in dreams, his fiancée entered holding out a package tied with red ribbon. She was dressed also in the style of dreams—in a white dress and soundless white shoes. He wanted to embrace her, but suddenly felt sick, his head whirled, and she in the meantime related that the newspapers were writing extraordinary things about him but that her mother still did not want them to marry. Probably there was much more of this and that, but his memory failed to overtake what was receding—and trying at least not to disperse what he had managed to wrest from his dream, Luzhin stirred cautiously, smoothed down his hair and rang for dinner to be brought. After dinner he had to play, and that day the universe of chess concepts revealed an awesome power. He played four hours without pause and won, but when he was already sitting in the taxi he forgot on the way where it was he was going, what postcard address he had given the driver to read and waited with interest to see where the car would stop.

The house, however, he recognized, and again there were guests, guests—but here Luzhin realized that he had simply returned to his recent dream, for his fiancée asked him in a whisper: “Well, how are you, has the sickness gone?”—and how could she have known about this in real life? “We’re living in a fine dream,” he said to her softly. “Now I understand everything.” He looked about him and saw the table and the faces of people sitting there, their reflection in the samovar—in a special samovarian perspective—and added with tremendous relief: “So this too is a dream? These people are a dream? Well, well . . .” “Quiet, quiet, what are you babbling about?” she whispered anxiously, and Luzhin thought she was right, one should not scare off a dream, let them sit there, these people, for the time being. But the most remarkable thing about this dream was that all around, evidently, was Russia, which the sleeper himself had left ages ago. The inhabitants of the dream, gay people drinking tea, were conversing in Russian and the sugar bowl was identical with the one from which he had spooned powdered sugar on the veranda on a scarlet summer evening many years ago. Luzhin noted this return to Russia with interest, with pleasure. It diverted him especially as the witty repetition of a particular combination, which occurs, for example, when a strictly problem idea, long since discovered in theory, is repeated in a striking guise on the board in live play.

The whole time, however, now feebly, now sharply, shadows of his real chess life would show through this dream and finally it broke through and it was simply night in the hotel, chess thoughts, chess insomnia and meditations on the drastic defense he had invented to counter Turati’s opening. He was wide-awake and his mind worked clearly, purged of all dross and aware that everything apart from chess was only an enchanting dream, in which, like the golden haze of the moon, the image of a sweet, clear-eyed maiden with bare arms dissolved and melted. (The Defense, 132–34)

I dreamt of this at night—saw myself fleeing from my grandfather and carrying away with me a toy, or a kitten, or a little crab pressed to my left side. I saw myself meeting poor Lloyd, who appeared to me in my dream hobbling along, hopelessly joined to a hobbling twin while I was free to dance around them and slap them on their humble backs.

I wonder if Lloyd had similar visions. It has been suggested by doctors that we sometimes pooled our minds when we dreamed. One gray-blue morning he picked up a twig and drew a ship with three masts in the dust. I had just seen myself drawing that ship in the dust of a dream I had dreamed the preceding night. (“Scenes from the Life of a Double Monster,” Stories, 616–17)

Sometimes I attempt to kill in my dreams. But do you know what happens? For instance I hold a gun. For instance I aim at a bland, quietly interested enemy. Oh, I press the trigger all right, but one bullet after another feebly drops on the floor from the sheepish muzzle. In those dreams, my only thought is to conceal the fiasco from my foe, who is slowly growing annoyed. (Lolita, 43)

Another almost perfect “Dunne” deal, as this is exactly what happens to Humbert, in surreal terms of his waking life, when he attempts to kill Quilty at least five years later.

Another almost perfect “Dunne” deal, as this is exactly what happens to Humbert, in surreal terms of his waking life, when he attempts to kill Quilty at least five years later.

Same date, later, quite late. I have turned on the light to take down a dream. It had an evident antecedent. Haze at dinner had benevolently proclaimed that since the weather bureau promised a sunny weekend we would go to the lake Sunday after church. As I lay in bed, erotically musing before trying to go to sleep, I thought of a final scheme how to profit by the picnic to come. I was aware that mother Haze hated my darling for her being sweet on me. So I planned my lake day with a view to satisfying the mother. To her alone would I talk; but at some appropriate moment I would say I had left my wristwatch or my sunglasses in that glade yonder—and plunge with my nymphet into the wood. Reality at this juncture withdrew, and the Quest for the Glasses turned into a quiet little orgy with a singularly knowing, cheerful, corrupt and compliant Lolita behaving as reason knew she could not possibly behave. At 3 A.M. I swallowed a sleeping pill, and presently, a dream that was not a sequel but a parody revealed to me, with a kind of meaningful clarity, the lake I had never yet visited: it was glazed over with a sheet of emerald ice, and a pockmarked Eskimo was trying in vain to break it with a pickax, although imported mimosas and oleanders flowered on its gravelly banks. I am sure Dr. Blanche Schwarzmann would have paid me a sack of schillings for adding such a libidream to her files. Unfortunately, the rest of it was frankly eclectic. Big Haze and little Haze rode on horseback around the lake, and I rode too, dutifully bobbing up and down, bowlegs astraddle although there was no horse between them, only elastic air—one of those little omissions due to the absentmindedness of the dream agent. (Lolita, 49–50)

I could not shake off the feeling of its all being a nightmare that I had had or would have in some other existence, some other sequence of numbered dreams. (Look at the Harlequins! 174)

A curious analogue to the dream experiment.

A curious analogue to the dream experiment.

He stretched, he passed his palms over his <warm> hairy legs, unglued and cupped himself, <with an odd spinning and light-headed sensation> and almost instantly Sleep, with a bow, handed him the key of its city: he understood the meaning of all the lights, <honking> sounds, and <women’s gazes> perfumes as everything blended into a single blissful image. Now he seemed to be in a mirrored hall, which wondrously opened on a watery abyss, water glistened in the most unexpected places: he went toward a door past the perfectly credible motorcycle which his landlord was starting with his red heel, and, anticipating indescribable bliss, Franz opened the door and saw Martha standing near the bed <sitting on the edge of the bed>. Eagerly he approached but Tom kept getting in the way; Martha was laughing and shooing away the dog. Now he saw quite closely her glossy lips, her neck swelling with glee, and he too began to hurry, undoing buttons, pulling a blood-stained bone out of the dog’s jaws, and feeling an unbearable sweetness welling up within him; he was about to clasp her hips <almost touched her> but suddenly could no longer contain his boiling ecstasy. (King, Queen, Knave, 74–75)

Yes, everything about her was excruciating and somehow irremediable, and only in my dreams, drenched with tears, did I at last embrace her and feel under my lips her neck and the hollow near the clavicle. But she would always break away, and I would awaken, still throbbing <sobbing, vskhlipyvaya in the original>. . . . Once, at Christmas, before a ball to which they were all going without me, I glimpsed, in a strip of mirror through a door left ajar, her sister powdering Vanya’s bare shoulder blades; on another occasion I noticed a flimsy bra in the bathroom. For me these were exhausting events, that had a delicious but dreadfully draining <sladko, dulcet, in the original> effect on my dreams, although never once in them did I go beyond a hopeless kiss (I myself do not know why I always wept so when we met in my dreams). (The Eye, 79–80)

When he had dozed off on the train, he had dreamt a dream grown out of something that Sonia had said. In the dream she pressed his head to her smooth shoulder and bent over him, tickling him with her lips, murmuring warm muffled words of tenderness, and now it was hard to separate fancy from fact. (Glory, 119–20)

. . . at night he dreamed of coming across a young girl lying asprawl on a hot lonely beach <some semi-naked young things on a deserted beach> and in that dream a sudden fear would seize him of being caught by his wife. (Laughter in the Dark, 17)

On the night of the twelfth, he dreamt that he was surreptitiously enjoying Mariette while she sat, wincing a little, in his lap during the rehearsal of a play in which she was supposed to be his daughter. (Bend Sinister, 158)

Singularly enough, I seldom if ever dreamed of Lolita as I remembered her—as I saw her constantly and obsessively in my conscious mind during my daymares and insomnias. More precisely: she did haunt my sleep but she appeared there in strange and ludicrous disguises as Valeria or Charlotte, or a cross between them. That complex ghost would come to me, shedding shift after shift, in an atmosphere of great melancholy and disgust, and would recline in dull invitation on some narrow board or hard settee, with flesh ajar like the rubber valve of a soccer ball’s bladder. I would bind myself, dentures fractured or hopelessly mislaid, in horrible chambres garnies where I would be entertained at tedious vivisecting parties that generally ended with Charlotte or Valeria weeping in my bleeding arms and being tenderly kissed by my brotherly lips in a dream disorder of auctioneered Viennese bric-à-brac, pity, impotence and the brown wigs of tragic old women who had just been gassed. (Lolita, 238–39)

The gist, rather than the actual plot of the dream, was a constant refutation of his not loving her. His dreamlove for her exceeded in emotional tone, in spiritual passion and depth, anything he had experienced in his surface existence. This love was like an endless wringing of hands, like a blundering of the soul through an infinite maze of hopelessness and remorse. They were, in a sense, amorous dreams, for they were permeated with tenderness, with a longing to sink his head onto her lap and sob away the monstrous past. They brimmed with the awful awareness of her being so young and so helpless. They were purer than his life. What carnal aura there was in them came not from her but from those with whom he betrayed her—prickly-chinned Phrynia, pretty Timandra with that boom under her apron—and even so the sexual scum remained somewhere far above the sunken treasure and was quite unimportant. (Pale Fire, 192)

Novels of the Montreux period contain erotic dreams of the increasingly untender kind that Humbert called “libidreams.”

Novels of the Montreux period contain erotic dreams of the increasingly untender kind that Humbert called “libidreams.”

She moved her head to make him move his to the required angle and her hair touched his neck. In his first dreams of her this re-enacted contact, so light, so brief, invariably proved to be beyond the dreamer’s endurance and like a lifted sword signaled fire and violent release. (Ada, 39)

He could rely on two or three dreadful dreams to imagine her, in real, or at least responsible, life, recoiling with a wild look as she left his lust in the lurch to summon her governess or mother, or a gigantic footman (not existing in the house but killable in the dream—punchable with sharp-ringed knuckles, puncturable like a bladder of blood), after which he knew he would be expelled from Ardis. < . . . > Next morning, his nose still in the dreambag of a deep pillow contributed to his otherwise austere bed by sweet Blanche (with whom, by the parlor-game rules of sleep, he had been holding hands in a heartbreaking nightmare—or perhaps it was just her cheap perfume), the boy was at once aware of the happiness knocking to be let in. He deliberately endeavored to prolong the glow of its incognito by dwelling on the last vestiges of jasmine and tears in a silly dream; but the tiger of happiness fairly leaped into being. (Ada, 97)

That night, in a post-Moët dream, he sat on the talc of a tropical beach full of sun-baskers, and one moment was rubbing the red, irritated shaft of a writhing boy, and the next was looking through dark glasses at the symmetrical shading on either side of a shining spine with fainter shading between the ribs belonging to Lucette or Ada sitting on a towel at some distance from him. Presently, she turned and lay prone, and she, too, wore sunglasses, and neither he nor she could perceive the exact direction of each other’s gaze through the black amber, yet he knew by the dimple of a faint smile that she was looking at his (it had been his all the time) raw scarlet. (Ada, 520–21)

Person, this person, was on the imagined brink of imagined bliss when Armande’s footfalls approached—striking out both “imagined” in the proof’s margin (never too wide for corrections and queries!). (Transparent Things, 102)

I have noticed, or seem to have noticed, in the course of my long life, that when about to fall in love or even when still unaware of having fallen in love, a dream would come, introducing me to a latent inamorata at morning twilight in a somewhat infantile setting, marked by exquisite aching stirrings that I knew as a boy, as a youth, as a madman, as an old dying voluptuary. The sense of recurrence (“seem to have noticed”) is very possibly a built-in feeling: for instance I may have had that dream only once or twice (“in the course of my long life”) and its familiarity is only the dropper that comes with the drops. The place in the dream, per contra, is not a familiar room but one remindful of the kind we children awake in after a Christmas masquerade or midsummer name day, in a great house, belonging to strangers or distant cousins. The impression is that the beds, two small beds in the present case, have been put in and placed against the opposite walls of a room that is not a bedroom at heart, a room with no furniture except those two separate beds: property masters are lazy, or economical, in one’s dreams as well as in early novellas. In one of the beds I find myself just awoken from some secondary dream of only formulary importance; and in the far bed against the right-hand wall (direction also supplied), a girl, a younger, slighter, and gayer Annette in this particular variant (summer of 1934 by daytime reckoning), is playfully, quietly talking to herself but actually, as I understand with a delicious quickening of the nether pulses, is feigning to talk, is talking for my benefit, so as to be noticed by me. My next thought—and it intensifies the throbbings—concerns the strangeness of boy and girl being assigned to sleep in the same makeshift room: by error, no doubt, or perhaps the house was full and the distance between the two beds, across an empty floor, might have been deemed wide enough for perfect decorum in the case of children (my average age has been thirteen all my life). The cup of pleasure is brimming by now and before it spills I hasten to tiptoe across the bare parquet from my bed to hers. Her fair hair gets in the way of my kisses, but presently my lips find her cheek and neck, and her nightgown has buttons, and she says the maid has come into the room, but it is too late, I cannot restrain myself, and the maid, a beauty in her own right, looks on, laughing.

That dream I had a month or so after I met Annette, and her image in it, that early version of her voice, soft hair, tender skin, obsessed me and amazed me with delight—the delight of discovering I loved little Miss Blagovo. (Look at the Harlequins! 101–3)

My sexual life is virtually over but—I saw you again, Aurora Lee, whom as a youth I had pursued with hopeless desire at high-school balls—and whom I have cornered now fifty years later, on a terrace of my dream. Your painted pout and cold gaze were, come to think of it, very like the official lips and eyes of Flora, my wayward wife, and your flimsy frock of black silk might have come from her recent wardrobe. You turned away, but could not escape, trapped as you were among the close-set columns of moonlight and I lifted the hem of your dress—something I never had done in the past—and stroked, moulded, pinched ever so softly your pale prominent nates, while you stood perfectly still as if considering new possibilities of power and pleasure and interior decoration. At the height of your guarded ecstasy I thrust my cupped hand from behind between your consenting thighs and felt the sweat-stuck folds of a long scrotum and then, further in front, the droop of a short member. Speaking as an authority on dreams, I wish to add that this was no homosexual manifestation but a splendid example of terminal gynandrism. Young Aurora Lee (who was to be axed and chopped up at seventeen by an idiot lover, all glasses and beard) and half-impotent old Wild formed for a moment one creature. But quite apart from all that, in a more disgusting and delicious sense, her little bottom, so smooth, so moonlit, a replica, in fact, of her twin brother’s charms (sampled rather brutally on my last night at boarding school), remained inset in the medallion of every following day. (The Original of Laura, 201–7)

This occurs not infrequently: You come to, and see yourself, say, sitting in an elegant second-class compartment with a couple of elegant strangers; actually, though, this is a false awakening, being merely the next layer of your dream, as if you were rising up from stratum to stratum but never reaching the surface, never emerging into reality. Your spellbound thought, however, mistakes every new layer of the dream for the door of reality. (King, Queen, Knave, 20)

I dreamed a loathsome dream, a triple ephialtes. First there was a small dog; but not simply a small dog; a small mock dog, very small, with the minute black eyes of a beetle’s larva; it was white through and through, and coldish. Flesh? No, not flesh, but rather grease or jelly, or else perhaps, the fat of a white worm, with, moreover, a kind of carved corrugated surface reminding one of a Russian paschal lamb of butter—disgusting mimicry. A cold-blooded being, which Nature had twisted into the likeness of a small dog with a tail and legs, all as it should be. It kept getting into my way, I could not avoid it; and when it touched me, I felt something like an electric shock. I woke up. On the sheet of the bed next to mine there lay curled up, like a swooned white larva, that very same dreadful little pseudo dog. . . . I groaned with disgust and opened my eyes. All around shadows floated; the bed next to mine was empty except for the broad burdock leaves which, owing to the damp, grow out of bedsteads. One could see, on those leaves, telltale stains of a slimy nature; I peered closer; there, glued to a fat stem it sat, small, tallowish-white, with its little black button eyes . . . but then, at last, I woke up for good. (Despair, 106–7)

And presently he found out that he could not live without her, and presently she found out that she had had quite enough of hearing him talk of his dreams, and the dreams in his dreams, and the dreams in the dreams of his dreams. (The Real Life of Sebastian Knight, 159)

He had spent most of the day fast asleep in his room, and a long, rambling, dreary dream had repeated, in a kind of pointless parody, his strenuous “Casanovanic” night with Ada and that somehow ominous morning talk with her. Now that I am writing this, after so many hollows and heights of time, I find it not easy to separate our conversation, as set down in an inevitably stylized form, and the drone of complaints, turning on sordid betrayals that obsessed young Van in his dull nightmare. Or was he dreaming now that he had been dreaming? (Ada, 198)

He heard Ada Vinelander’s voice calling for her Glass bed slippers (which, as in Cordulenka’s princessdom too, he found hard to distinguish from dance footwear), and a minute later, without the least interruption in the established tension, Van found himself, in a drunken dream, making violent love to Rose—no, to Ada, but in the rosacean fashion, on a kind of lowboy. She complained he hurt her “like a Tiger Turk.” He went to bed and was about to doze off for good when she left his side. (Ada, 415–16)

He dreamed that he was speaking in the lecturing hall of a transatlantic liner and that a bum resembling the hitch-hiker from Hilden was asking sneeringly how did the lecturer explain that in our dreams we know we shall awake, is not that analogous to the certainty of death and if so, the future—(Ada, 561)

This ancient notion, which gave the title to Calderón’s famous play, and its logical extension (death is awakening), are assayed in a number of Nabokov’s fictions, most directly in Invitation to a Beheading.

This ancient notion, which gave the title to Calderón’s famous play, and its logical extension (death is awakening), are assayed in a number of Nabokov’s fictions, most directly in Invitation to a Beheading.

By an implacable repetition of moves it was leading once more to that same passion which would destroy the dream of life. Devastation, horror, madness. (The Defense, 246)

It is frightening when real life suddenly turns out to be a dream, but how much more frightening when that which one had thought a dream—fluid and irresponsible—suddenly starts to congeal into reality! (The Eye, 106)

Strange: all dread had gone. The nightmare had melted into the keen, sweet sensation of absolute freedom, peculiar to sinful dreams. (Laughter in the Dark, 66–67)

The original continues: “for life is a dream” (omitted in the English version).

The original continues: “for life is a dream” (omitted in the English version).

Maybe it is all mock existence, an evil dream; and presently I shall wake up somewhere; on a patch of grass near Prague. A good thing, at least, that they brought me to bay so speedily. (Despair, 221)

And yet, ever since early childhood, I have had dreams. . . . In my dreams the world was ennobled, spiritualized; people whom in the waking state I feared so much appeared there in a shimmering refraction, just as if they were imbued with and enveloped by that vibration of light which in sultry weather inspires the very outlines of objects with life; their voices, their step, the expressions of their eyes and even of their clothes—acquired an exciting significance; to put it more simply, in my dreams the world would come alive, becoming so captivatingly majestic, free and ethereal, that afterwards it would be oppressive to breathe the dust of this painted life. But then I have long since grown accustomed to the thought that what we call dreams is semi-reality, the promise of reality, a foreglimpse and a whiff of it; that is, they contain, in a very vague, diluted state, more genuine reality than our vaunted waking life which, in its turn, is semi-sleep, an evil drowsiness into which penetrate in grotesque disguise the sounds and sights of the real world, flowing beyond the periphery of the mind—as when you hear during sleep a dreadful insidious tale because a branch is scraping on the pane, or see yourself sinking into snow because your blanket is sliding off. But how I fear awakening! (Invitation to a Beheading, 91–92)

Fantastic imagery appearing deceptively real and utterly believable. Nabokov often invokes the notion of a dream director responsible for these grotesque shows, with a self-suggesting analogy of fiction-writing.

Fantastic imagery appearing deceptively real and utterly believable. Nabokov often invokes the notion of a dream director responsible for these grotesque shows, with a self-suggesting analogy of fiction-writing.

A sophisticated dreamer (for to see dreams is an art form in its own right), he most often had the following dream . . . (Camera Obscura, 96). <The description of the dream that follows is markedly different from the English version below, more elaborate and plausible: the Russian Horn (renamed Rex in English) gets four aces one after the other, then draws a joker. The English text goes:>

Having cultivated a penchant for bluff since his tenderest age, no wonder his favorite card-game was poker! He played it whenever he could get partners; and he played it in his dreams: with historical characters or some distant cousin of his, long dead, whom in real life he never remembered, or with people who—in real life again—would have flatly refused to be in the same room with him. In that dream he took up, stacked together, and lifted close to his eyes the five dealt to him, saw with pleasure the joker in cap and bells, and, as he pressed out with a cautious thumb one top corner and then another, he found by degrees that he had five jokers. “Excellent,” he thought to himself, without any surprise at their plurality, and quietly made his first bet, which Henry the Eighth (by Holbein) who had only four queens, doubled. Then he woke up, still with his poker face. (Laughter in the Dark, 141)

It was all very nice, very prim at that party. We talked about things that did not concern him, and I knew that if I mentioned his name there would flash in the eyes of each of them the same sacerdotal alarm. And when I suddenly found myself wearing a suit cut by my neighbor on the right, and eating my vis-à-vis’ pastry, which I washed down with a special kind of mineral water prescribed by my neighbor on the left, I was overcome by a dreadful, dream-significant feeling, which immediately awakened me—in my poor-man’s room, with a poor-man’s moon in the curtainless window. I am grateful to the night for even such a dream: of late I have been racked by insomnia. It is as if his agents were accustoming me beforehand to the most popular of the tortures inflicted on present-day criminals. (“Tyrants Destroyed,” Stories, 449)

And the dream I had: that garlicky doctor (who was at the same time Falter, or was it Alexander Vasilievich?) replying with exceptional readiness, that yes, of course it sometimes did happen, and that such children (i.e., the posthumously born) were known as cadaverkins. As to you, never once since you died have you appeared in my dreams. Perhaps the authorities intercept you, or you yourself avoid such prison visits with me. (“Ultima Thule,” Stories, 501–2)

I remember once dreaming of her: I dreamt that my eldest girl had run in to tell me the doorman was sorely in trouble—and when I had gone down to him, I saw lying on a trunk, a roll of burlap under her head, pale-lipped and wrapped in a woolen kerchief, Nina fast asleep, as miserable refugees sleep in godforsaken railway stations. (“Spring in Fialta,” Stories, 425)

Now he found himself running (by night, ugly? Yah, by night, folks) down something that looked like a railway track through a long damp tunnel (the dream stage management having used the first set available for rendering ‘tunnel,’ without bothering to remove either the rails or the ruby lamps that glowed at intervals along the rocky black sweating walls). (Bend Sinister, 58)

On the eve of the day fixed by Quist he found himself on the bridge: he was out reconnoitring, since it had occurred to him that as a meeting place it might be unsafe because of the soldiers; but the soldiers had gone long ago, the bridge was deserted, Quist could come whenever he liked. Krug had only one glove, and he had forgotten his glasses, so could not reread the careful note Quist had given him with all the passwords and addresses and a sketch map and the key to the code of Krug’s whole life. It mattered little however. The sky immediately overhead was quilted with a livid and billowy expanse of thick cloud; very large, greyish, semitransparent, irregularly shaped snowflakes slowly and vertically descended; and when they touched the dark water of the Kur, they floated upon it instead of melting at once, and this was strange. Further on, beyond the edge of the cloud; a sudden nakedness of heaven and river smiled at the bridge-bound observer, and a mother-of-pearl radiance touched up the curves of the remote mountains, from which the river, and the smiling sadness, and the first evening lights in the windows of riverside buildings were variously derived. Watching the snowflakes upon the dark and beautiful water, Krug argued that either the flakes were real, and the water was not real water, or else the latter was real, whereas the flakes were made of some special insoluble stuff. In order to settle the question, he let his mateless glove fall from the bridge; but nothing abnormal happened: the glove simply pierced the corrugated surface of the water with its extended index, dived and was gone.

On the south bank (from which he had come) he could see, further upstream, Paduk’s pink palace and the bronze dome of the Cathedral, and the leafless trees of a public garden. On the other side of the river there were rows of old tenement houses beyond which (unseen but throbbingly present) stood the hospital where she had died. As he brooded thus, sitting sideways on a stone bench and looking at the river, a tugboat dragging a barge appeared in the distance and at the same time one of the last snowflakes (the cloud overhead seemed to be dissolving in the now generously flushed sky) grazed his underlip: it was a regular soft wet flake, he reflected, but perhaps those that had been descending upon the water itself had been different ones. The tug steadily approached. As it was about to plunge under the bridge, the great black funnel, doubly encircled with crimson, was pulled back, back and down by two men clutching at its rope and grinning with sheer exertion; one of them was a Chinese as were most of the river people and washermen of the town. On the barge behind, half a dozen brightly coloured shirts were drying and some potted geraniums could be seen aft, and a very fat Olga in the yellow blouse he disliked, arms akimbo, looked up at Krug as the barge in its turn was smoothly engulfed by the arch of the bridge.

He awoke (asprawl in his leather armchair) and immediately understood that something extraordinary had happened. It had nothing to do with the dream or the quite unprovoked and rather ridiculous physical discomfort he felt (a local congestion) or anything that he recalled in connection with the appearance of his room (untidy and dusty in an untidy and dusty light) or the time of the day (a quarter past eight p.m.; he had fallen asleep after an early supper). What had happened was that again he knew he could write. (Bend Sinister, 168–70)

He had fallen asleep at last, despite the discomfort in his back, and in the course of one of those dreams that still haunt Russian fugitives, even when a third of a century has elapsed since their escape from the Bolsheviks, Pnin saw himself fantastically cloaked, fleeing through great pools of ink under a cloud-barred moon from a chimerical palace, and then pacing a desolate strand with his dead friend Ilya Isidorovich Polyanski as they waited for some mysterious deliverance to arrive in a throbbing boat from beyond the hopeless sea. (Pnin, 109–10)

That exhilaration of a newly acquired franchise! A shade of it he seemed to have kept in his sleep, in that last part of his recent dream in which he had told Blanche that he had learned to levitate and that his ability to treat air with magic ease would allow him to break all records for the long jump by strolling, as it were, a few inches above the ground for a stretch of say thirty or forty feet (too great a length might be suspicious) while the stands went wild, and Zambovsky of Zambia stared, arms akimbo, in consternation and disbelief. (Ada, 123)

Seeing one’s dead father in a dream is a particularly poignant theme in Nabokov’s fiction.

Seeing one’s dead father in a dream is a particularly poignant theme in Nabokov’s fiction.

That night Mark had an unpleasant dream. He saw his late father. His father came up to him, with an odd smile on his pale, sweaty face, seized Mark under the arms, and began to tickle him silently, violently, and relentlessly. He only remembered that dream after he had arrived at the store where he worked, and he remembered it because a friend of his, jolly Adolf, poked him in the ribs. For one instant something flew open in his soul, momentarily froze still in surprise, and slammed shut. (“Details of a Sunset,” Stories, 81).