![]()

![]()

AP. HILL was dead. On the morning of April 2 he had ridden from a meeting with Lee into Federal troops who had recently pierced Hill’s lines. Hill and his courier were attempting to intimidate two Yankees into surrender when the Federals called their bluff at a range of less than twenty yards. Hill had lived a long time in pain. Mercy attended his death: the rifle ball tore through his heart and out of his back. Hill spun around in his saddle and crashed face first to the ground already dead.

Robert Lee burst into tears when he heard the news. “He is now at rest,” Lee pronounced, “and we who are left are the ones to suffer.” During the week that followed Hill’s death on April 2, Lee was more right than he knew. Considerable suffering lay ahead for the Army of Northern Virginia.1

Walter Herren Taylor and Elizabeth Selden Saunders were married. Having secured Lee’s leave to leave the headquarters as the headquarters was about to leave, too, Taylor commandeered the locomotive of an “ambulance train” and overhauled another train bound for Richmond. Taylor’s courier followed with the horses. When Taylor arrived in Richmond, the government, the army, and anyone else able to do so either had fled or were fleeing the Confederate capital. Walter and Betty had made careful plans, however, and during the early minutes of April 3,1865, the Reverend Dr. Charles Minnigerode, Rector of St. Paul’s Church, blessed the marriage in the presence of some family and friends at the home of Lewis D. Crenshaw on West Main Street.

By the time Taylor set out to fulfill his promise to rejoin Lee, it was four o’clock in the morning. Most of the official Confederates (government and military) had left; a mob of residents were looting warehouses containing military rations of food, and lapping and scooping from gutters the whiskey that flowed from barrels dutifully broken to prevent people from drinking it. Fires raged out of control in much of the city, as Taylor and his courier rode over Mayo’s Bridge to the south bank of the James.2

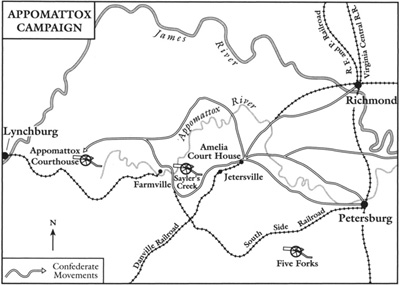

Meanwhile, the Army of Northern Virginia marched at 8:00 P.M. Lee mounted Traveller and rode across to the north bank of the Appomattox River, posted himself at a fork in the road, and helped direct traffic while his troops filed past in the dark. At most Lee commanded 30,000 men; the army retained 200 guns and moved with 1,000 wagons. But of course Lee commanded these soldiers, weapons, and supplies only if they were able to disengage from the general battle that had continued for most of April 2, march through the dark over unfamiliar roads, and rendezvous at Amelia Court House on April 4. Lee planned to have rations ready at Amelia and move on from there to Burkeville, junction of the Danville and Southside railroads. Then Lee hoped to march (or perhaps ride) down the railroad to Danville and a union with Joseph E. Johnston and the residue Army of Tennessee.

Lee made or revealed no specific plans for his movements beyond Burkeville; the junction with Johnston was essentially inference. Clearly Lee’s principal task now was to escape from Grant’s army; until he accomplished that, any plan was pure conjecture.

Lee did have reason to hope that the Federals would not pursue him aggressively. Certainly George B. McClellan and George G. Meade had been cautious following their successes at Sharpsburg (Antietam) and Gettysburg. But Grant was neither McClellan nor Meade. Still the Federals faced a formidable challenge to occupy Petersburg and Richmond, to leave their established lines of supply and communication, and to maneuver masses of men who had been sealed in trenches for nearly ten months.3

On the morning of April 3 as Lee rode west with Longstreet, the Confederates were once more in open country out of the labyrinthine trench systems and for the moment at least beyond Grant’s grasp. By dark the vanguard of Lee’s retreat had marched 21 miles, and Lee had had some contact with all of the various commands that had escaped from Petersburg and had heard no discouraging words from units that had been north of Petersburg and the James.4

On April 4, however, the retreat began to unravel. When Lee rode into Amelia Court House, he found no food for his men. He had ordered rations to Amelia from Richmond. In effect Lee had moved his base of supplies from Richmond to Danville, and he planned to feed the army from rations sent by rail as he marched. If he were able to follow this plan, Lee’s supply line would grow shorter each day the army marched, and Grant’s supply line would lengthen if he tried to follow. But Lee’s sound planning meant nothing if the army went hungry, and on April 4 the army was already hungry.

It is now impossible to know what happened to Lee’s directive to deliver food to Amelia Court House, if in fact a written order ever existed. If the retreat from Petersburg had ever been more than a desperate gamble, this failure to have rations ready for the troops at Amelia Court House would rank with the loss of Special Orders No. 191 during the Maryland Campaign of 1862 or the several blunders at Gettysburg among the hypothetical imponderables of the Confederate War. On April 4, those absent rations were crucial to Lee and his soldiers. Because Lee found no rations at Amelia Court House, he had to stop his march and dispatch foraging parties with wagons into the countryside. All this consumed time, and Lee could not afford time. He spent twenty-four hours in foraging forays, collected very little food, and later concluded, “This delay was fatal, and could not be retrieved.”5

While details of men searched the surrounding country in relatively fruitless foraging, more troops arrived, and finally Lee learned that Richard S. Ewell was nearby with his troops from the defenses of Richmond. However much Lee needed to bring his army back together, in this case the troops were concentrating where Lee could not feed them, and the crisis increased as each new body of soldiers reached the rendezvous.

On April 5, Lee ordered the march resumed and hoped that the trainload of rations ordered up from Danville would meet the column. By this time many of the soldiers were weak from hunger, and the horses that carried the cavalry and pulled wagons, gun carriages, and caissons were struggling with their burdens. Straggling and freelance foraging increased as Lee’s thin ranks constantly shrank.

Then Lee’s worst fears materialized; about one o’clock that afternoon, as Lee and Longstreet approached Jetersville, they discovered Philip Sheridan’s cavalry ahead of them. Rooney Lee shared the bad news: two corps of Federal infantry were throwing up field fortifications across their projected path.

Edward Porter Alexander remembered, “I never saw Gen. Lee seem so anxious to bring on a battle in my life as he seemed this afternoon.” Battle was clearly one of Lee’s options—perhaps a showdown fight before even more Yankees overtook his army—the Army of Northern Virginia would overrun its enemies or die trying in the most literal way possible. But the more Rooney reported his observations, the clearer it became that attack would be futile. So Lee decided to change his route of march; his immediate objective became the village of Farmville, to which he ordered supplies sent from Lynchburg. As it happened, I. M. St. John, the new commissary general, reported later on the 5th that he had 80,000 rations at Farmville. Speed was essential, more so now than ever. Lee had to break free from Federal infantry that had outmarched and overtaken him. He had to keep his troop units together to fight off cavalry attacks. And he had to get to Farmville before the enemy in order to feed the men. Lee ordered an all-night march for April 5—6.6

To the degree that regiments, brigades, divisions, and corps still existed in the Army of Northern Virginia, Longstreet’s corps led the way, followed by Richard H. Anderson (who now commanded his old division and what was left of the divisions of George E. Pickett, Bushrod Johnson, and Henry Heth), Ewell (with his contingent of Richmond defensive forces and reserves), and John B. Gordon (now in command of what had once been Ewell’s corps). Many of these troops units were very nearly imaginary; Ewell’s reserve force all but evaporated en route as 6,000 men became less than 3,000. And when this confused column attempted to move, a gap opened between Pickett’s division and the units ahead of him, effectively dividing the army.7

Disaster came at Sayler’s Creek, a tributary of the Appomattox River, just east of Farmville. Lee witnessed it. He rode back to a ridge above the creek, and there he saw the remnants of almost half of his army in desperate flight from the enemy.

“My God! has the army been dissolved?” Lee asked rhetorically.

Anderson and Ewell had had to deploy infantry in battle formations to combat the assaults of Union cavalry, and the gap between the two halves of the army widened. At Sayler’s Creek a Federal infantry corps overtook the stragglers and surrounded them. Within a very short while roughly half of Anderson’s corps and all of Ewell’s men were lost to Lee’s army; some were killed or wounded; most were captured. What Lee saw from the ridge was the backwash from an uneven battle, broken men in flight from an enemy that seemed omnipresent.

With Lee was William Mahone and a division of soldiers; Lee directed Mahone to face his troops toward the valley of Sayler’s Creek and stem Federal pursuit. Lee then seized a battle flag and began to try to rally those scared, sad men stumbling past him. Mahone returned to him, took the battle flag, and took over the task of restoring order and organization to the fugitives. Lee raised his field glasses and began to think about what to do now.

Then a Confederate general officer “of exalted grade” emerged from the rout. One of Lee’s staff officers called the commanding general’s attention to his dispirited subordinate. Lee never averted his eyes. He was in search of some solution to the problem in which this disgraced officer had participated.

“General,” Lee said to the man, “take those stragglers to the rear out of the way of Mahone’s troops. I wish to fight here.”8

While Lee with Mahone was attempting to stem the tide and cover the rear of the army, Gordon was engaged in another frantic fight on Sayler’s Creek just downstream from Lee’s position. Already Gordon had lost many of the wagons he had been trying to guard; now he fought to save what remained of his command. Lee ordered Mahone to hold his ground on the ridge line above Sayler’s Creek until the survivors had made their way across the Appomattox River and into Farmville. Then Mahone was to follow, and the engineers left in Lee’s army were supposed to burn the two bridges spanning the river.

This day, April 6, had been worse than sad. Lee lost perhaps 8,000 men; Ewell and Lee’s son Custis were among the Confederates captured; the Army of Northern Virginia now numbered no more than 12,000 infantry and 3,000 cavalry. Grant had 80,000 soldiers at or near the scene. And to crown the day of debacle, the Confederates waited too late to burn one of the bridges over the Appomattox River. Instead of finding rations and respite in Farmville, the men had to continue the march, grab whatever food they could, and as Lee later admitted, “All could not be supplied.” Needless to say, Lee reacted to this “blunder with … warmth and impatience.”9

On April 7, Lee’s troops slogged ahead with decreasing speed. The roads were muddy from rains; both men and animals were weaker; the force was so small that men had to march with the artillery and wagons to protect them; and periodically during the afternoon Lee had to stop and deploy infantry to keep the Federals at bay. Dark on April 7 found Lee with Longstreet only about three miles beyond Farmville near a place called Cumberland Church.10

During the evening a courier found Lee and handed him a message received through enemy lines. It was from U. S. Grant.

General: The results of the last week must convince you of the hopelessness of further resistance on the part of the Army of Northern Virginia in this struggle. I feel that it is so, and regard it as my duty to shift from myself the responsibility of any further effusion of blood, by asking of you the surrender of that portion of the C. S. Army known as the Army of Northern Virginia.

Lee read the note and handed it to Longstreet, who read it and returned it to Lee with the two-word judgment—“Not yet.”11

Lee was not so sure. At the very least he wanted to know his options, so he wrote out a response and dispatched it to Grant without revealing its content to anyone present.

I have read your note of this date. Though not entertaining the opinion you express of the hopelessness of further resistance on the part of the Army of N. Va.,—I reciprocate your desire to avoid useless effusion of blood, & therefore before considering your proposition, ask the terms you will offer on condition of its surrender.12

The wagons, such as they were, kept rolling through the dark and reached New Store before midnight. The infantry resumed the march during the night and cavalry assumed a rear guard. Now the goal was Appomattox Station on the Southside Railroad. There Lee hoped to feed his troops once more and then attempt to break through the Federals and strike for Danville.13

By this point in the retreat, however, the soldiers sensed an end to this corporate agony. Alexander began to hear calls from his artillery batteries: “Don’t surrender no ammunition!” His gunners were determined to fire all the shot and shells they had before the end.

On April 8, pressure from the Federals relaxed to the point that the Southerners marched “uninterrupted.” This was “the first quiet day of the march, since leaving Amelia.” There was an ominous cause for the quiet, though: pursuing columns were marching along roads parallel to Lee’s route in an effort to reach Appomattox before Lee did.14

During the morning of the 8th Lee took advantage of the tranquility to lie down on the ground to rest. Artillery staff officer William Nelson Pendleton found Lee and imposed upon his peace to speak for a group of officers that had gathered the previous evening and decided the time had come to surrender. Although educated at West Point, Pendleton was more than anything else a tedious, loquacious cleric (Episcopal) disguised as chief of artillery. Lee heard his message and emphatically disagreed. The precise tone and tenor of Lee’s response varies with the several accounts of the incident. Lee did fail to tell Pendleton that he had already commenced negotiations of sorts with Grant and in them used the word “surrender.” As Alexander observed, “I believe that Gen. Lee took no one into his confidence as to his intentions, or as to this correspondence with Gen. Grant; preferring as his hand became the harder to play, to play it more & more alone.”15

On the afternoon of April 8, Lee took time to dispense justice upon three of his senior subordinates. He relieved from command and removed from his army Richard H. Anderson, George E. Pickett, and Bushrod Johnson. The more information Lee learned about Pickett’s actions at Five Forks on April 1 (i.e., leaving his command to attend Thomas Rosser’s shad bake), the more culpable this broken man seemed to have been in the virtual destruction of his division. After Sayler’s Creek on April 6, Johnson told Lee that the enemy had decimated his division. But soon after Johnson’s report, Lee encountered Henry A. Wise and his brigade of Johnson’s division very much intact. Obviously Johnson had fled his command in the course of the battle. Anderson may have been that general officer “of exalted grade” whom Lee had so summarily dismissed in the wake of Sayler’s Creek. At any rate, this trio felt Lee’s wrath, and Lee’s righteousness endured to the end of his tenure in command.16

Some time after dark on April 8, Lee received his second communication from Grant:

GENERAL,—Your note of last evening in reply to mine of the same date, asking the conditions on which I will accept surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia, is just received. In reply I would say that, peace being my great desire, there is but one condition I would insist upon,—namely, that the men and officers surrendered shall be disqualified for taking up arms again against the government of the United States until properly exchanged. I will meet you, or will designate officers to meet any officers you might name for the same purpose, at any point agreeable to you, for the purpose of arranging definitely the terms upon which the surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia will be received.

Lee pondered his reply and then wrote a very curious note to Grant:

I recd at a late hour your note of today. In mine of yesterday I did not intend to propose the surrender of the Army of N. Va.—but to ask the terms of your proposition. To be frank, I do not think the emergency has arisen to call for the surrender of this Army, but as the restoration of peace should be the sole object of all, I desired to know whether your proposals would lead to that and I cannot therefore meet you with view to surrender the Army of N. Va.—but as far as your proposal may affect the C.S. forces under my command & tend to the restoration of peace, I shall be pleased to meet you at 10 A.M. tomorrow on the old stage road to Richmond between the picket lines of the two armies.

Lee seemed to suggest that they raise the stakes, in effect, and discuss “the C.S. forces under my command” (i.e., all Confederate armies) and “the restoration of peace.” Did Lee propose that he and Grant negotiate the end of the war then and there? Grant could find out if he appeared at ten o’clock the next morning on the old stage road.17

Not long after he sent his note through the lines to Grant, Lee convened a council of war among his surviving subordinate commanders, Longstreet, Gordon, and Fitz Lee. These men led the two infantry corps and all the cavalry left with the Army of Northern Virginia—perhaps 10,000 men altogether.

Lee stood by a fire; Longstreet sat on a log; Gordon and Fitz Lee lounged on a blanket. Lee summarized their circumstance, read the notes from and to Grant, and asked the obvious question—what to do next. The answer, in retrospect, seemed obvious—attack. Trust trial by combat one last time.

But, and this was important, if Federal infantry were in force behind the Federal cavalry known to be blocking the route of march, then surrender was the only answer. Enemy infantry in strength in front of Lee’s army, together with the infantry in the rear of the column, would mean that the Confederates were essentially surrounded by an overwhelming Federal force. The only alternative to surrender would then be suicide.

Longstreet was to protect the rear, while Fitz Lee’s horsemen and Gordon’s infantry attacked the Federals in front. The troops were supposed to move at 1:00 A.M.; but Fitz Lee, with Lee’s blessing, delayed the advance until 5:00 A.M., almost first light.18

After a short nap, Lee dressed himself in the best uniform he possessed, complete with a red silk sash and sword, neither of which he usually wore. He rode to the front, which was not far away, and stationed himself on a hill behind Gordon’s troops. He heard the firing, but saw little of the ensuing fight. Finally, about 8:00 A.M., Lee sent his staff officer Charles Venable to find out what was happening.

Venable discovered that Gordon’s assault had succeeded at first. But as the Confederates advanced, Lee reported later, “A heavy force of the enemy was discovered opposite Gordon’s right, which, moving in the direction of Appomattox Court House, drove back the left of the cavalry and threatened to cut off Gordon from Longstreet. His [enemy] cavalry at the same time threatening to envelop his [Gordon’s] left flank, Gordon withdrew….” When Venable returned to Lee, Gordon’s message was, “Tell General Lee I have fought my corps to a frazzle, and I fear I can do nothing unless I am heavily supported by General Longstreet’s corps.”

Lee listened to this and proclaimed, “Then there is nothing left me but to go and see General Grant, and I would rather die a thousand deaths.”19

For members of the Army of Northern Virginia, the war was over. Most of them had sensed that end for some time. A week earlier, while the army was attempting to maintain a position in Petersburg long enough to evacuate the city under cover of darkness during the night of April 2, a staff officer noticed Lee “handsomely dressed,” and another soldier believed Lee’s uniform was new. Maybe Lee had dressed himself for surrender even then. But knowing the end was near and coming to emotional terms with defeat were very different matters. Someone heard Lee exclaim, “How easily I could be rid of this, and be at rest! I have only to ride along the line and all will be over!” Soon he regained control and professed, “But it is our duty to live.”20

At some point during this interim between defeat and surrender, Edward Porter Alexander appeared. Lee sat down upon a log and said to him, “Well here we are at Appomattox, & there seems to be a considerable force in front of us. Now, what shall we have to do today?”

Alexander just happened to have a very firm answer to Lee’s question; he had been thinking about such a contingency for some time. He was, as he remembered, “wound up to a pitch of feeling I could scarcely control.” He had made up his mind “that if ever a white flag was raised I would take to the bushes.”

Lee heard Alexander’s plan and passion to “scatter like rabbits & partridges in the woods & they could not scatter so to catch us.” Then Lee demonstrated that he, too, had thought about a guerrilla alternative to surrender. He had had to consider a guerrilla phase of this war, because he knew that Jefferson Davis was committed to just such a recourse. Lee rejected the partisan alternative, however; he had from the beginning believed that the South’s best chance lay in decisive victories in conventional battle. Lee feared anarchy far more than Yankees, and his concern for the social order saturated his response to Alexander.

Suppose I should take your suggestion & order the army to disperse & make their way to their homes. The men would have no rations & they would be under no discipline. They are already demoralized by four years of war. They would have to plunder & rob to procure subsistence. The country would be full of lawless bands in every part, & a state of society would ensue from which it would take the country years to recover. Then the enemy’s cavalry would pursue in the hopes of catching the principal officers, & wherever they went there would be fresh rapine & destruction.

And as for myself, while you young men might afford to go to bushwhacking, the only proper & dignified course for me would be to surrender myself & take the consequences of my actions.

When Lee completed his statement, Alexander recalled, “Then I thought I had never known before what a big heart & brain our general had.”21

Soon it became time to keep the appointment with Grant that Lee had proposed the previous evening. Four horsemen rode down the old stage road. George W. Tucker, the courier who had ridden with A. P. Hill the day Hill was killed, led the way with a white flag, followed by Lee and Walter Taylor and Charles Marshall from Lee’s staff. They met not Grant, but a Federal staff officer with a note from Grant, dated April 9.

GENERAL: Your note of yesterday is received. As I have no authority to treat on the subject of peace the meeting proposed for 10 A.M. today could lead to no good. I will state, however, General, that I am equally anxious for peace with yourself, and the whole North entertain the same feeling. The terms upon which peace can be had are well understood. By the South laying down their arms they will hasten that most desirable event, save thousands of human lives, and hundreds of millions of property not yet destroyed. Sincerely hoping that all our difficulties may be settled without the loss of another life….22

Lee dictated his reply to Marshall; but as he did, a rider approached from Lee’s rear at top speed. John Haskell, sent by Longstreet with orders to ride so fast as to kill his horse if necessary, brought a message to Lee that Fitz Lee thought he had discovered a route by which the army might escape. “What is it? What is it?” Lee asked, and then, “Oh, you have killed your beautiful mare! What did you do it for?” Haskell told Lee in private the nature of his errand; but Lee determined to continue his negotiations to surrender. As if to reinforce his resolve, guns commenced firing from the Federal side. Lee’s note read:

I received your note of this morning on the picket line whither I had come to meet you and ascertain definitely what terms were embraced in your proposal of yesterday with reference to the surrender of this army. I now request an interview in accordance with the offer contained in your letter of yesterday for that purpose.

Lee offered to wait for an answer and asked that the Federals suspend hostilities until Grant read his note. The Federal officer could only promise to deliver the note and return with a reply. Grant was difficult to find that morning; he seemed inclined to repay Lee’s actions over a truce after Second Cold Harbor with interest.

As Lee doubtless wondered what to do next, a second message arrived from Longstreet. Fitz Lee’s escape route was not as clear as he had believed at first.

On Longstreet’s front, Union Cavalry General George A. Custer decided to preempt his commanding general and try to bully Longstreet into surrendering to him. “Well, Sheridan & I are independent here today,” Custer told Longstreet, “& unless you surrender immediately we are going to pitch in.” Longstreet was unimpressed. “Pitch in as much as you like,” he responded.

While Lee waited in the road, Federal infantry advanced to the attack in accord with orders no one had or could countermand without Grant’s permission. Lee dispatched another note: “I ask a suspension of hostilities pending the adjustment of the terms of surrender of this army, in the interview requested in my former communication today.” The situation became tense. Someone shouted for Lee to get out of the way of the Federal infantry; a major bloodbath seemed about to commence.23

Lee did withdraw within his lines, and at the last moment before the shooting began in earnest, George G. Meade, who still commanded the Army of the Potomac, sent a note proclaiming a truce based upon the imminent surrender. Meade also suggested that Lee write another note to Grant through another point in the enemy line in the hope that he might receive it more rapidly. Accordingly, Lee dictated a third note to Grant:

General, I sent a communication to you today from the picket line whither I had gone in hopes of meeting you in pursuance of the request contained in my letter of yesterday. Maj. Gen. Meade informs me that it would probably expedite matters to send a duplicate through some other part of your lines. I therefore request an interview at such time and place as you may designate to discuss the terms of the surrender of this army in accord with your offer to have such an interview contained in your letter of yesterday.24

Whether he intended to or not, Grant was requiring Lee to grovel just to receive the opportunity to surrender his army. But Lee was well aware that war, the resort to physical force, is by definition a suspension of rules, laws, and civilized behavior. Victors can impose their will upon the vanquished. If his decision to “take the consequences of my actions” compelled Lee to humble himself, so be it. And, in accord with Lee’s conviction that “the great duty of life” was “the promotion of the happiness & welfare” of others, Lee likely believed that his personal pride was a small sacrifice, if he could salvage the honor of his army.

Meade’s truce and the search for Grant left Lee nothing to do until Grant responded to one or more of his notes. He rode back within his lines, stood alone in an apple orchard, and eventually said, “I would like to sit down. Is there any place where I can sit near here?” Alexander heard these words and hurried to fashion a seat from fence rails under an apple tree. There Lee sat for nearly three hours.25

Then Orville E. Babcock of Grant’s staff appeared with a message from Grant:

Your note of this date is but this moment (11:50 A.M.) received. In consequence of my having passed from the Richmond and Lynchburg road to the Farmville and Lynchburg road I am at this writing about four miles west of Walker’s church, and will push forward to the front for the purpose of meeting you. Notice sent on this road where you wish the interview to take place will meet me.

Lee collected Marshall and his courier Tucker and rode with Babcock to Appomattox Court House.

Lee assigned Marshall the duty of finding a place to meet with Grant. Marshall settled upon the home of Wilmer McLean. This man had had a home near Manassas; one of the first artillery rounds fired in this war had crashed into McLean’s kitchen. After the Second Battle at Manassas, McLean had decided to remove himself and his family away from the war zone. McLean had moved to Appomattox Court House to escape combat; but now the war had found him again.

Lee rode into McLean’s yard, dismounted, and entered the house. He settled in the parlor to the left of the front door and awaited Grant. After a half-hour, Grant appeared. He was dressed in “rough garb,” fresh from the field, spattered with mud. Lee was “in full uniform which was entirely new and was wearing a sword of considerable value.” Both generals had clothed themselves carefully as they wanted others to see them—Grant no less than Lee.26

For a time the two men spoke of mutual experiences in the Mexican War. Then Lee shifted the conversation to the transaction at hand, and Grant wrote down terms of the surrender.

In accordance with the substance of my letter to you of the 8th instant I propose to receive the surrender of the Army of N. Va. on the following terms, to-wit:

Rolls of all the officers and men to be made in duplicate, one copy to be given to an officer designated by me, the other to be retained by such officer or officers as you may designate. The officers to give their individual paroles not to take up arms against the government of the United States until properly [Lee confirmed that Grant had intended writing “exchanged” after “properly”] and each company or regimental commander sign a like parole for the men of their command.

The arms, artillery, and public property to be parked and stacked and turned over to the officer appointed by me to receive them.

This will not embrace the side arms of the officers, nor their private horses or baggage. This done each officer and man will be allowed to return to their homes not to be disturbed by United States authority so long as they observe their paroles and the laws in force where they may reside.

Lee liked what he read. He did point out that Confederate cavalrymen and artillerists owned the horses they rode or drove. After some pause Grant agreed to allow the men who claimed a horse or mule to take the animal with them. Lee was pleased.

Lee asked Marshall to write out his response:

GENERAL: I have received your letter of this date containing the terms of surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia as proposed by you. As they are substantially the same as those expressed in your letter of the 8th instant, they are accepted. I will proceed to designate the proper officers to carry the stipulation into effect.

Lee and Grant, once they had signed these documents, shook hands. Lee bowed to all present and strode onto the porch. “Orderly! Orderly!” Lee called, and Tucker brought Traveller. Lee helped replace the bridle and mounted. Grant appeared on the porch of the McLean House. Seeing Lee about to depart, the Federal took off his hat; others did the same. Lee tipped his own hat, turned Traveller, and rode away.27

Lee returned to his troops one last time. They greeted him with an amalgam of love and awe. He had arranged with Grant to have rations of food delivered to these men, many of whom had not received rations since they had left Petersburg a week ago. Lee tried to speak to his soldiers; but his words were lame—I have done my best for you … go home and be good citizens. It made no difference; the soldiers provided the eloquence. They wanted to hug him; they settled for a touch and some expression of their affection. Then one of the men said, “Farewell, General Lee. I wish for your sake and mine that every damned Yankee on earth was sunk ten miles in hell!” The day required some benediction.28

Lee went into the orchard by himself and paced. Soldiers and strangers came and went; Lee spoke very little. He seemed in “one of his savage moods,” and his staff officers knew better than to disturb him. He was coming to terms with defeat, surrender, the end—almost forty years of career and life gone.29

Lee needed to grieve. He had seen and known so much death and loss. In four years he had lost almost all that he owned and many whom he loved. A daughter was dead, along with a daughter-in-law and two grandchildren. His wife had become an invalid, and he knew his own health had declined dramatically. Arlington was gone. And Lee had mourned so many of his men—Robert S. Garnett and John A. Washington from his first staff; Stonewall Jackson at Chancellorsville; Dorsey Pender, Richard B. Garnett, Lewis A. Armistead, William Barksdale, and James Johnston Pettigrew at Gettysburg; Jeb Stuart, Dodson Ramseur, John Pegram, A. P. Hill, and many more—more than 650,000 soldiers on both sides.

He was a soldier; he should have been accustomed to death. But this war had produced not only death in the immediate family. It concluded with the death of Lee’s extended family—the Army of Northern Virginia. Surrender was death raised to an enormous power. Lee would need to grieve a long time. But at last the suffering was over, and he was at rest.