Chapter 7

NURTURING THE YOUNG STORYTELLER

— By Nadine Majette James —

Listen—your child is reliving the moment, retelling an event from his or her own unique perspective. Nothing could be more valuable than capturing those moments! After all, crafting a memoir is not just for adults.

This chapter explores memoirs from a younger writer’s point of view, as well as how crafting a memoir can preserve childhood’s most precious times. It provides tips for introducing children to the craft of memoir and encouraging them as they gain confidence and comfort with self-expression at home and at school. You’ll also find ways to involve children in family memoir projects, including grandparent interviews and other age-appropriate activities.

The Foundation for Storytelling Begins When We’re Very Young

Your toddler looks on and listens as you talk to your mom in Virginia about how to make her sweet potato pie. She or he sees shapes magically appear as you move the pen or you hit each key and notices that you give each shape a name as you recite your list: sugar, eggs, milk …

You might not realize it, but even with something as simple as a shopping list, you’ve already modeled how people express themselves through writing. Add crayons, markers, paint, paper, and photos to the mix, and children are ready to share with you the pictures in their heads.

Often the pictures are about birthdays, outings, and family visits—in other words, they are your child’s first memoirs. These self-expressions of a child are fleeting, but you can give them permanence by simply dating them, adding a caption, and saving them in a file or shoe box. Most important, a few words of praise—“Very good. I’m going to save this one for Grandma’s birthday card!”—go a long way in helping your child feel confident about storytelling and enthusiastic about memoir projects.

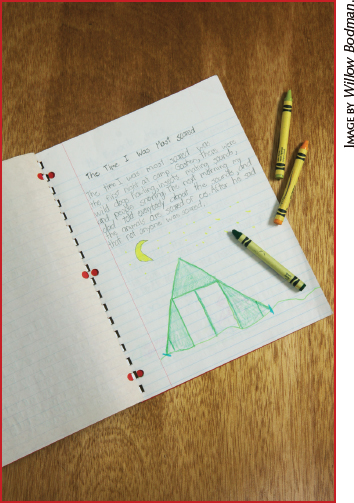

Child’s Journal: “The Time I was Most Scared.” A fourth-grader recalls a time when he was afraid during a Boy Scout camping trip. His father helped him and other scouts overcome their fears.

To further build your child’s confidence and enthusiasm, consider scanning these “first memoirs” into the computer to demonstrate their importance and so that you have them for future memoir projects. Most printers now have a scanning feature. If not, you can scan them at your local drugstore, supply/copy center, or public library.

Connecting the Dots in the Story

As you know, you are your child’s first teacher. When it comes to children creating their own memoirs, they learn patience, creativity, and achievement by watching you put together scrapbooks, lay out and sew your quilts, and protect your favorite handwritten recipes and cookbooks as you gourmet up the kitchen.

When you become a role model by pursuing your own craft and memoir projects, the children in your life not only watch your actions, but they see the connections you make between the words, stamps, photos, fabrics, and other ingredients, and the story you are telling. In this way, children understand that this connection is not only to story, but to their own story, or identity—the family present and past, the history and culture that helped to create them and helps them know who they are.

Imagine the conversations you could have:

“See this one square in the quilt? It came from your Great-Uncle Will’s baseball uniform. We used to call him Lightfoot. I bet you didn’t know that he played for the Negro National League in the 1940s.”

“Do you believe this photo is your Aunt Dolly? Was she cute or what! You have her green eyes, and she loved rock music as much as you do. Grandad had a fit when she snuck off to go see the Beatles in New York.”

“I got this recipe for sweet rolls from Grandma, even though I could never get her to write it down. I had to watch her bake and take notes as best I could. Hand me that …”

Fast forward a few years later to your fifth-grader now faced with a rigorous writing assessment test in school: The teacher places an old wooden chest in the center of the classroom. “Your assignment is to create a story explaining where it came from, what it was used for, and who previously owned it. Be creative and include as many details as possible.”

Now who’s going to ace the test? The children who grew up with storytelling and self-expression, of course! Ideas and memory, descriptions, colors, and textures will flood their brains. Best of all, they will be able to visualize an answer, access those pictures, and express them in words.

So as your child watches and listens to you, so does he build his skills and abilities.

It is so important that you listen to your child. I’m not recommending you pull off the highway to capture that thirty-four-word garbled blab about the fairy tale–themed birthday party. Still, tuning in and listening to your child’s stories and descriptions helps show that his or her point of view and experiences are important to you. That is a real confidence-builder.

With the passing of years, the collected bits of sticky notes and papers filled with your child’s words and saved for later, hidden away in a special place, can become a treasure chest of childhood wonder.

In a larger sense, these bits and pieces become part of the family heritage that your child is connected to. Peggy Kaye, author of Games for Writing, chronicles that journey in her book. She reminds us how storytelling is the very foundation of learning to express ourselves through writing.

Before we move on to tips and tricks for working with children on memoir projects, here is a short note about reading to them.

Reading Plays a Role

When books are read to children, they hear the words and use their imaginations. Connecting the story to their own lives expands their world. In other words, “It’s not just me that has a scary dream; it’s the boy in the story, too!” Classic fairy tales and folktales endure to this day because of their universality, and they are a gold mine when it comes to reaching children with the joys of reading and storytelling. The excitement children feel for a story they love encourages them to tell their own stories. It’s imitation at its best.

Sample Projects and Activities

Here are some activities you can do with children, or set them up to work on independently.

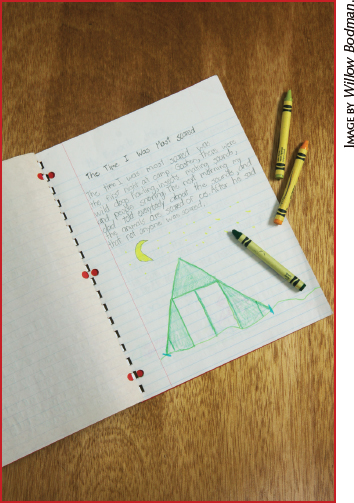

A “My First” Timeline

If your story involves the progression of time, simple timelines can be made by decorating index cards and gluing them to a string to show different important dates. For example, “My First” is a great place to start for a child’s timeline: my first steps, my first words, my first day at school.

A timeline can also serve as a memoir project outline, as different old photos or news-clippings are attached to the index cards as a way of organizing them into your memoir.

Child’s first timeline. Items found around the house such as crayons, index cards, and yarn can be used to chronicle your child’s life.

Homemade Family Folktales

A folktale is a story that has been handed down orally through the generations. So why not create family folktales? They can be small, like when the family first came to America’s shores. Or they can be big, like when Great-Grandma Jane was arrested in Virginia in 1961 during segregation for refusing to move herself and her pupils to the back of the bus on a field trip. What happened as a result? Who bailed her out? What happens when the story is retold and embellished? These are the ingredients for great family folktales.

Nothing’s better than a homemade family storybook, because the ingredients are homegrown. Your child recognizes the characters, the setting, and the emotions. When you and your child together put these elements in the form of a book or memory project (calendar, scrapbook, cookbook, voice recording, etc.), your child’s self-esteem and family connections grow. And most importantly, it’s fun!

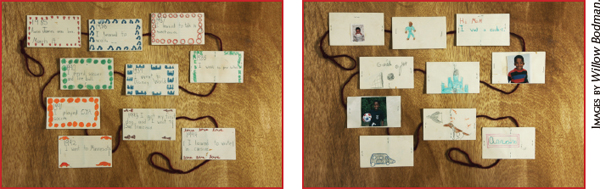

Family folktale book: “The Wonderful Marvelous Incredibly Radical Totally Awesome Day.” A favorite storybook inspires a young storyteller’s imaginative tale.

Family Newspapers

This kind of project is good for ages seven and up. If you are working with younger children, let them help you.

A family newspaper is a good project to do on your computer. It also lends itself beautifully to a family event such as a wedding, reunion, or holiday. The trick to creating a family newspaper is using all the elements of a regular newspaper, such as a front-page banner with the newspaper name, front-page headlines, and so on.

Let your child be the editor-in-chief and relate things from his or her point of view. If you have a group, each person can be “delegated a news beat” and contribute one piece for the paper. Here are some suggestions for getting started:

1. Create a lead story. What happened?

2. Add a drawing, photos, and even a cartoon.

3. Add some human interest stories (like the role your child played at the wedding—was she the flower girl?).

4. Add a funny human interest story, e.g., Cousin Jay ate too much cake and threw up.

5. Believe it or not, children love survey questions. Let them pick a question, such as “What was your favorite part of the wedding—the ceremony or the reception, or both?” They will “survey” a couple of family members and put the results in the paper.

6. Older children can even do a one-paragraph opinion editorial (an “op-ed”)—their own take on the event.

Holiday Newsletters

If you enjoy sending out an annual holiday letter to family and friends, consider having your child write and illustrate part of the letter. It means so much to family that’s far away, and it helps the child reflect on the past year and goals for the year ahead.

Helping Children Interview Family Members

Back in the early years of my teaching career, I invited my second-graders to celebrate Grandparents Day by becoming involved in a special project called “My Grandparent Remembers.” As part of the activity, I hoped to expand my students’ understanding of their own history and heritage by having them ask family members a broad range of questions with a slight twist. All the questions began with “when you were my age.”

One day my students were sharing their interview videos in class. In one video, a little boy asked his grandfather, “When you were my age, what was your favorite song?” Without hesitation, his grandfather burst into a song from his own childhood. I maintained my composure, but inside I was simultaneously laughing and crying for many reasons. I thought about the many memories these interviews had captured, and all the families that would be forever changed in the process. I was convinced that the “interview” is the key to family memoir. The interview transformed a simple school project into a great story.

The children loved doing these projects and remembered them as they grew older. I was lucky enough to hear from one of my former second-graders whom I had encouraged as a storyteller. She said her family still had her grandparent interview. Years later, one of her stories was published in the Scholastic book, The Best Teen Writing of 2012. In the copy she gave me, her inscription read, “Thank you so much for your work as my teacher helping me along my way to becoming a writer.”

When you begin a memoir project with a child, you know you’re going to have fun, but where those storytelling moments will take you in the future can be more than you or your child can foresee in the present moment. The project could be the beginning of something that neither of you has imagined.

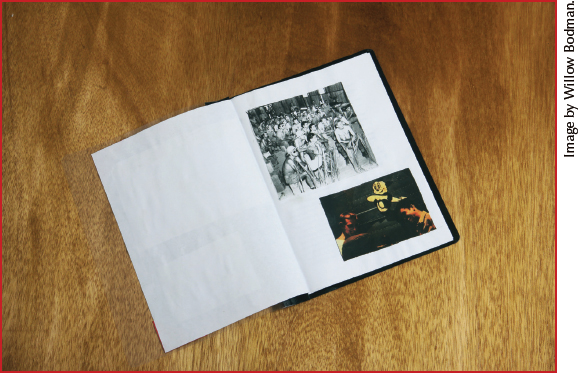

“My Grandparent Remembers.” Second-grader Emma illustrated her grandparent interview book. She interviewed her “mom’s mom.”

Interviewing is important to creating family memoir projects because it supplies the details: day-to-day activities, special events, and what loved ones thought about them. Your child will ask open-ended questions and find out what Grandma and Grandpa saw, thought, dreamed, and feared. Hearing the responses allows your child to step back into history, to walk in a grandparent’s footsteps—better yet, to walk with the grandparent, while recording unique stories that cannot be gathered by any other method of historical documentation.

You might think that our senior relatives have better things to do than to answer questions about themselves, but think again. Just about everybody loves that type of attention. Plus, they might be so surprised that the young people are interested in their life experiences that they’ll spend quite a bit of time coming up with answers.

Create a Questionnaire—Good Questions Make All the Difference

The purpose of the interview questions is to create a path for the story. Questions guide the discussion and keep things on track, ensuring that basic but oh-so-precious information will be covered. Remember that young children might need several sessions to complete an interview with a family member. Record each interviewing session in the way that works for you: taking notes by hand, typing into a computer, or using a voice or video recorder.

Help children develop questions that cover a range of events and include a balance of “factual” and reflective questions. You might want to send the interviewee a list of suggested questions from which he or she may choose. However, certain information should be gathered consistently, such as the interviewee’s date and place of birth. Beginning with questions about early childhood remembrances taps stronger memories and allows the interviewee to become more reflective. I have also observed that as interviewees answer the questions, a strong bond is created between the interviewer and the interviewee, and both are happy that they have created this bit of history for the next generation. You’ll be amazed by how seriously children take their job of interviewing grandparents and family. They really get into it!

Questions Appropriate for Elementary-Age Interviewers

• What was your name at birth? (Ask about nicknames)

• Where were you born?

• What was the date of your birth?

• How much did the following cost when you were my age?

Gasoline per gallon

Gasoline per gallon

Postage stamp

Postage stamp

A soft drink

A soft drink

A candy bar

A candy bar

• When you were my age, what or who was your favorite?

Sports star

Sports star

Song

Song

Movie star

Movie star

School subject

School subject

• What was school like when you were my age?

• What did you like best/hate most about school?

• What time did you have to go to bed on a school night?

• What were your chores at home?

• What was the fashion when you were my age? What did you wear to school?

“My Grandfather Makes History.” Later, as a middle school student, Emma wrote an essay about her paternal grandfather’s participation in a flying mission during World War II. He was the radio man on the bomber Lucky. Her father told her that her grandfather, along with the rest of the crew, received a Distinguished Flying Cross, which at the time was the highest award given to an airman. Emma’s riveting essay was saved for all to read.

Questions Middle or High School Students Might Ask:

• Describe your family, including the role of your mother and father in the household and their occupations.

• Describe your family life and your daily life.

• Describe your school, friends, hobbies, and organizations.

• What were your family’s political or religious affiliations?

• What are your recollections of the town or city where you were born?

• How did you get your job?

• Describe any cultural, social, or religious activities: concerts, lectures, parties, religious observances.

• Were the lives of women and men different or similar when you were growing up?

• When were you considered a “grown-up”? How is that different from or similar to what we consider “grown-up” today?

Conducting an interview takes children beyond their own world. For example, ask children what they know about history and the response may often be, “I don’t know.” The concept of “family history” might be abstract to them with little or no connection to their own lives. When they interview family members, children learn that people are “History!” Furthermore, by the end of the interviews, grandparents or senior family members perceived as ordinary old people will indeed be recognized for the awesome people they are. Their lives are indeed remarkable. The time spent organizing and arranging an interview for your child is well worth it!

What Is Age-Appropriate?

Keep in mind the age of your storyteller when starting a project. Here are some guidelines:

Ages 0–3: Read to them. Yes, even when they are babies, before they can talk. Hearing stories creates the fertile soil from which a child’s own stories will someday take root.

Ages 4–6: Let them help you create a family memoir project. Include their words, photos, and drawings. This is when role-modeling and enthusiasm are so important. For example, “Let’s write a story for the photos!” or “Help me decorate Grandma’s cookbook. Will you draw a picture for it?”

Ages 7 on up: You’ll need to set up your child with materials, including computer software if he or she is working digitally. Take a few minutes to talk with your child to create the plan or outline for the project. From there, you take on the role of supporter. Remember that your child might not be able to finish it in one sitting (very few do). You might take what they do accomplish and include it as part of the family memoir.

Children will often write down what people say—or what they think people might have said. These inventions, too, are a precious part of children’s storytelling. So even though your child wasn’t there when relatives from Vietnam were rescued to begin a new life in America, and no one ever said, “Welcome to America. Land of the free and home of the brave,” please consider leaving it as is, and don’t discourage your child from putting his or her own words into characters’ mouths. It’s part of your child’s enthusiastic storytelling and perspective. Getting to share is what it’s all about.

The Ripple Effect of Connections

One of the gifts of working with children is that it supports your own projects about your own childhood. Their drawings and words will trigger your own memories of being little, which will re-ignite memories such as the bad taste of old-fashioned medicine, falling asleep in your mom’s lap, or the sounds of city life around your apartment building. All of these triggers will allow your own stories to come forward more clearly.

Keep in Mind

• The foundation for storytelling begins at a very young age as your child listens to you.

• Simple arts and crafts, and talking and listening to your children, can build their skills and self-esteem.

• Write down children’s stories and what they say for use in a childhood memoir project later on.

• Read storybooks and folktales to children to expand their world through the universality of emotions and themes.

• Family stories can be turned into precious homemade family folktales.

• Include your child in your own memoir activities.

• Interviewing family members is a process of joy and discovery for children; help them create a questionnaire that’s age-appropriate.