The world is big and I mean to have a look at it before it gets dark.

John Muir

I was certainly glad to leave Scotland in mid-March for the start of GTAM. I travelled to Sheffield for a couple of nights with Charles, gaining some amusement from his frantic last-minute preparations as mine had passed in discreet privacy. We took a bus from Sheffield to Heathrow direct and flew via Tangier to change at Casablanca and on to Agadir. Pas de problème but oh, such interminable boredom. We took a grand taxi and could almost feel the driver deflating as he realised we’d been many times before so he couldn’t go over the recognised rate, which is stiff enough. (What airport doesn’t pile it on?) Within cities the petit taxis are a fast and easy way of moving about, the cost being no more than a bus at home. There may be a meter, there may not. Negotiate, as ever. Though I’m often rude about them, tour companies can serve a useful purpose in giving an easy first introduction to a new country and its differing practicalities. Morocco is tough for the innocent traveller. The friendly welcome from the El Bahia Hotel pushed the air journey into oblivion.

This is a small hotel near the top end of the town, handy for buses and with nearby good but cheap eating options, and I’ve seen us there for odd days without ever seeing the sea or the tourist parts of Agadir. Agadir, while partly a sprawling holiday trap, is also a busy ‘county town’, and one can make what one will of the place. We were only in Agadir overnight, breakfasting on the square and dozing the miles away in a bus to Taroudant, fifty miles to the east.

Before the bus departed, an endless succession of touts and beggars fought their way up the narrow passage: boys selling chewing gum or cakes, a water-seller, a blind man who chanted surahs from the Koran endlessly, another who gave a pathetic spiel and then lifted his garb to display a colostomy, and a youth who sold several plastic propellers on the end of sticks. Two beamy women jammed between the seats in the narrow passage and entertained with their verbal and physical wrestling. A carrier bag wedged in the inadequate storage shelf escaped, showering down on mother and child their supply of sick bags, Sidi Ali, Yopla, oranges and bread. A bus journey beats TV any day. Many of the posh buses have videos but most, mercifully, have stopped working. Everyone muttered “Bismilah” (“In the name of God”) as they settled into their cramped seats. There were quite a few tourists on the bus and they gave us some odd looks as, when we stepped out, we were hugged and ceremoniously greeted by several people. These included Ali and the deaf and dumb shoeshine boy. We were also greeted by Aziz, still effectively Ali’s boss. More about him later.

The boss of the Hotel Roudani then embraced us as did Moussa, the cheery waiter whom we have known for years. We had our usual rooms on the terrace, looking down on the square with its solitary palm and, from the rooftop, a view northwards to the white fangs of Awlim and Tinergwet—the last big GTAM peaks of the Atlas which we hoped to traverse eventually. The Roudani is not a classified hotel but is cheap and friendly and has that prime position. The shower is heated with a boiler which looks like something out of a 19th century children’s encyclopedia. A fluffy cat with her suckling kittens lay in a wooden box—when not trying to drag her offspring into Charles’ bed. We made a rendezvous with Ali for 1700 and went off to the other square for one of our traditions, a cake lunch in the patisserie by the souk entrance. We bought oranges and Sidi Harazem, bottled water from a pilgrim spring near Fes (Sidi Ali and the fizzy Oulmès come from a Middle Atlas hill station). We went over our schedule again, with copies for everyone, but had to scamper ‘home’ to beat a thunder plump that turned the streets into rivers.

The only drawback of the Roudani is that it faces five daily loud-speaking, pre-recorded calls to prayer and, for good measure, the Fejr (dawn) call comes at 0500 and adds half an hour of Koranic reading. (The other calls come less violently: Dhuhr, noon; ’Asr, between zenith and sunset; Maghrib, sunset; and ’Acha, about the time of the evening meal.)

Most of the day was spent on logistics and we met Hosain who would complete our basic quartet. We liked him at once: a tough, cheery character which was a relief as we’d received a posed studio photograph that made him look like a real Mr Glum. Charles visited the hammam (public steam baths) while I went to tea with the family whose house we often used up in Tagmout. The children were named Mustapha, Nadia, Rachid and Fatima, and their old father had died leaving them in difficulties. The two youngest had been sad and withdrawn and used to sit for hours with me in the house, or followed like puppies outside. I came to love them dearly. My welcome was boisterous. Mustapha, at seventeen, was handsome, spoilt and feckless. He was tried out as a potential muleteer and discarded (but then with Ali as standard, who could match up?) and Nadia was into high heels and western make-up—the typical teenager. They had to rent their house to the Tagmout schoolteachers and move down to Taroudant, where their widowed mother works and keeps the home going.

Charles and I met up again to eat at the Roudani, Moussa bringing us each an orange pressé on the house. Moussa (Moses) is a real character. He used to work at another café and when he moved to the Roudani most of his regular customers moved too. With panache and humour he keeps everyone happy. At the end of a meal some first-timer will be presented with a bill about ten times the true price while Moussa creates consternation; those of us in the know find it difficult to hold in our laughter. On one occasion, I observed a middle-aged American couple being unnecessarily objectionable and, at the end, Moussa quoted them a quite outrageous sum. They handed this and more over with the dismissive gesture of the spoilt rich and for a moment Moussa hesitated, before walking stiffly away. He gave me the briefest wink as he passed.

I’m convinced Moroccans can read visitors quicker than a TV commercial. They spend so much time in personal contact that they acquire, without even knowing, great facility at people watching. Moussa, in the course of serving the meal, will have unerringly chosen the one most likely to panic when selected for his regular game. He had tremendous authority too. When two kids started a fight in front of the Roudani he simply pulled them apart and held each by the collar while delivering a lecture before sending them on their way. There’s a scary homeless youth who roams round the city, foaming at the mouth and sometimes roaring like a lion. This raving figure appearing among the tables can be startling, to put it mildly, but Moussa will put his arms round the mad character and lead him away without fuss: practical ‘care in the community’. There’s also a snotty young Down’s syndrome boy who is allowed to sit in the café. On his arrival he will go round to be given a hug or a kiss by all the regulars. Not a few beggars will depart with food at the end of day, quite a normal way for restaurateurs to fulfil their religious obligations. How stiff and self-centred our public life is in comparison.

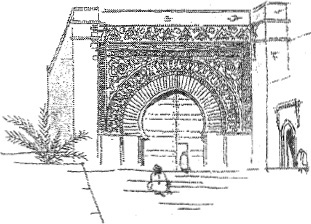

Taroudant is very old, older than Marrakech for instance, as it was captured by the Almoravid dynasty in 1030. Marrakech was founded in 1062, before William became The Conqueror. Taroudant was later the Merinid dynasty’s capital in the south and the Saadians spent twenty years gaining strength there before conquering north of the Atlas. The city still nestles within strong ramparts and the feel of the place can’t have changed much in centuries. Taroudant is a mini Marrakech, without the hassles.

The dawn call to prayer found us waiting for the bus office to open. Ali saw all the baggage aboard, fetched Hosain and we still had time for a coffee. We had a double seat each so snoozed most of the way along the Sous plains by Oulad Berhil and Tafinegoult but roused for the road up to the Tizi n’ Test, the argan trees petering out as we gained height, the mountains rising above in a seemingly impossible barrier. The road makes huge sweeps back and forth, in one place cut into the cliff like an open-sided tunnel, the tortuous ascent ending at a casual col marked by a small café, 2092 m, having climbed from near sea level in a single haul. Those with serious vertigo travel with their eyes shut. The road was crisp with new snow, the air bracing.

The road wound along on a high in-and-out traverse which opened out views to the northern peaks above the Nfis river: Igdat and Oumzra which, Insh ’Allah (God willing), we’d climb, weeks, months ahead. They were enhanced by the new whitewashing of snow and, from the zigzags of the onward descent of the bus, the whole Toubkal massif glittered silver, a surprisingly small area when seen from this angle, small but tough and demanding, with the highest Atlas peaks.

At Talat n’ Yacoub the bus stopped at a blacksmith’s and he welded a rattling luggage rack while we stretched our legs and looked down to the old Goundafa kasbah (castle) by the Oued Nfis. We would pass it too, Insh ’Allah, the phrase slipping out as readily as from any local.

There was the usual tea stop at Ijoukak where our GTAM route would cross the Test road so both memories and expectations were accumulating. We off-loaded at Asni and ‘Mohammed the taxi’ (Ie grand noir) chanced to be there so stowed our rucksacks etc. in his car while we went off for a tagine in our favourite café before he ran us up to Imlil. This Mohammed was called le grand noir to differentiate him from all the other Mohammeds but he was now old and grey and shrunken compared to thirty years previous. He’d nursed only two vehicles up and down the tough Imlil piste (dirt track) in that time, but retired after that year. In both of his taxis his head had completely worn through the lining and much of the metal of the roof. He was big. He took us to near the school and I reckon we did well to make it in one trip up to Mohammed’s house with our baggage. Our host was in Marrakech but we were family enough to be looked after by his wives. They brought our permanent Atlas gear out of the store and we had the biggest ever sorting out and packing. Ali and Hosain were kitted out with the gear supplied by Berghaus and Brasher, which sometimes made us look like a stage show of identikit comics. They were impressed both by the gear and our insistence on all of us being equally equipped.

The following day saw everything done so we had time to sit in the Café Soleil with Mohammed that night, drinking excellent coffee. It was a wolf-cold night with the moon just trimmed from full. We had our gear taken down to the square by mules and then waited for a tourist minibus to arrive, disgorge, and then take Charles, me and all the luggage direct to the Hotel Ali in Marrakech while Mohammed took Ali and Hosain in his car. For most of the day our hotel room looked a shambles while we had a complex repacking: leaving one bag each which we’d want for a half-way break, a bag of gear for some friends to bring in May, a big case to act as a store in the hotel (from which groups would add and subtract to order) and then the array that would go with us to the start: a rucksack and a small bag each besides the communal gear.

We had lunch in the Bahja, where the haj owner (one who has made his pilgrimage to Mecca) had recently been on a cookery programme on British TV. This was followed by coffee in the Iceberg, which serves beer and the best coffee in the medina (old town). Ali went to the bus station and we two to the railway station to sort out travel tickets. I rang the Hotel des Remparts in Essaouira as we’d be ending there in high season (they placed me with “Ah, le vieux Ecossais avec la barbe grise”), and luckily met a homeward-bound tourist who agreed to post letters to those who’d be joining us along the way. A last coffee in the Argana with life on the Fna square fading as the moon strengthened was traditional too, as was tramping out some laundry in the bath which would dry on the roof overnight.

At 0500 we carried down some gear. The garden opposite was already noisy with bulbuls. We called a petit taxi and saw Ali and Hosain depart for a 0600 CTM bus to Taza. They both had a large rucksack and something in each hand. Apart from local fresh food purchasing in Taza we were now at maximum loading. All we had to do was shift everything to Taza. Ali and Hosain were off a week before us in order to search, find and purchase two mules and their accoutrements. I’m sure Ali had never had so much money in his pocket before. At dawn we went up onto the rooftop to make sure nobody had stolen the Atlas overnight. Swifts screamed overhead like children in the sheer joy of motion. We took a No. 1 bus along to the Gueliz (new town). I don’t think the signs on the bus made much sense to the crush of passengers: ‘Niet roken, Verbandtrommel’, or ‘Voor de streep geen staanplaatsen’. The heady scent of orange blossom filled Avenue Mohammed V. We went in to the covered market to top up our range of spice jars and shop for a few special items. We eyed a Jaques Majorelle painting in a gallery: the price was more than the cost of our entire trip. We resisted the temptation to buy any books. In the evening we saw Farouk, the hospitable patron of the Hotel Ali and left more mail for the UK. There was a note from Mohammed Achari in the Bou Guemez so we confirmed our dates via the driver who’d brought the note. I’m always astonished how communications and arrangements work so effectively.

In bed that night the idea of a story for a book came to me and I lay awake for a long time developing the idea and even wrote down the first sentence. As I couldn’t carry dozens of books to read I determined to write one.

Charles and I then went to Rabat for five days, just marking time but with people to visit and plenty to see and do, the days passed quickly. We even winkled some maps out of the authorities. We spent time in the Oudaïas quarter and over the river in historic Salé, we visited the potteries and carpet souk, bookshops and favourite eating-places. Rabat is always very pleasant.

Having said that, I’ve a vivid picture of two kids dressed in tatters, cringing against a sea wall, blotto from solvent sniffing. Hidden away in the hills backing the capital, the mountains of dumped city garbage are covered with a vast bidonville (shanty town); in the fifty countries I’ve seen this is the most nauseous habitation I’ve ever encountered. If this book paints a somewhat idyllic picture I’m not unaware of the wretchedness too—whose origin is partly in the very prosperity of the hills. The picture is one that hangs in my own Scottish history gallery too.

In the Highlands enforced peace and assured crops led to a population explosion after Culloden and Waterloo. The surplus headed for the cities or overseas. Morocco does not have a diaspora option and the problem is colossal as is seen in the huge expansion of building in every town. High unemployment and a large young adult population does not help. In my lifetime, however, the overall prosperity of the country has grown prodigiously. What other African country can match Morocco?

Back in February 1965 during our first-ever visit, when I’d only been a few weeks in Morocco, I wrote in my log “This is a country to come to for months at a time and, even when older, it will attract me as much”. Time has certainly borne out that speculative statement. It would be easy to spend weeks in Rabat and Salé, exploring the coast or the other Imperial Cities of Meknes and Fes. Over the years I have. Fes, especially, is endlessly fascinating and such a contrast to Marrakech, a city of brains as against brawn, Fes foots a stately measure, Marra spins a Dervish dance. The Arab word for these lands is Maghreb-el-Aksa (the land of the furthest west), a nice echo of Europe’s Cap Finisterre (the end of the earth). It was slightly odd to start our venture by travelling to the furthest east of the country. Morocco is a corruption of Marrakch (Marrakech) and old maps have ‘City of Morocco’ against the town’s site while the country as a whole was designated by ‘Kingdom of Fes’ and ‘Kingdom of Morocco’, the twin areas of central dominance historically.

The train journey, Rabat to Taza, took much of a day and was uneventful: dozing, reading, eating and watching the world go by: Kenitra, Sidi Slimane, Sidi Kacem, Meknes, Fes, the big Idriss I lac (dam), long ascent to the tunnel (one way of dealing with the constriction of the Taza Gap) and then the accelerating run down to Taza. With our baggage we were slow off the train so missed available taxis. One came eventually, two coffees later. The old Hotel de la Poste was expecting us. Our balcony door was secured with string and the plumbing was home to poltergeists. We were given an ill-spelt letter from Ali and he arrived after supper, having left Hosain mule-minding in the medina. “All ready; we can go tomorrow,” he grinned. As we had expected a day or two in Taza this jolted us wide-awake.

Michael Collins, the pilot of Apollo 11 in 1969, described looking at our blue planet with its swirling cloud patterns and how he was able to trace the Atlas Mountains. A glance at any chart shows its distinctive line, like a breakwater across the northwest corner of Africa, holding back the oceanic vastness of the Sahara. The range runs from Atlantic seaboard to Tunisia but the highest, most spectacular part lies in Morocco. The early explorers called the mountains that look on Marrakech ‘The Great Atlas’. Even with modern transport we took days to reach the start.

“Great!” I chortled, a touch of disbelief in my laugh. We’d been two years, thirty years, all life on the way to this sudden tomorrow. I could only echo The New Road:

‘I would never take the nearer way anywhere, half the sport in life is starting and the other half is getting on the way, and everything is finished when it’s done.’

When I had called in to check with my home doctor about updating any of the recommended jags for Morocco he requested me to stand on the scales, measured my height, noted my age (some well-meaning directive so dictating) and then looked up a book of words to pronounce on the findings. With a twinkle in his eye he commented, “Well Hamish, I have to inform you that you are a bit overweight for your age and height and therefore should suggest you take some regular exercise, something like a bit of walking...”