Mount Atlas, a name so idly celebrated by the fancy of poets.

Gibbon

Shrill voices of children shouting the words of the Prophet in unison came from one house as we left the tidy village the next morning. Once the dogs had escorted us off their territory, we wandered on up into a slope of crowded cedars. With ravens on the crags, the calling of thrushes and the thin whispering of firecrests we could have been looking down on Rothiemurchus, although the comparison made me laugh outright. The scale is slightly different, Scotland has no nuthatches or Barbary apes, and there may even be leopards in the Atlas. Arbal on its spur appeared now and then and, beyond, the eye plunged down a thousand metres of forest, until the blue succession of fading tones disappeared in diaphanous whiteness. Nature’s call separated us but we agreed to meet at the col at the end of the Bou Iblane ridge we’d been following for several days. When I next saw Charles he was doing an Extreme up a vertical mud slope. The hillside was seamed with gullies, mud, scree, boulders and piecrust snow, all at a steep angle. Paths were ephemeral. I described the trees as ‘muscular’. (Something must have held them upright.) At 0800 we heard barking down at Arbal and assumed our other half was setting off. At 0900 we reached the col and I only had time to write-up the previous day’s doings in my log when our boisterous team arrived.

The view along the flank of Bou Iblane was impressive: a skier’s dream of white snow. Ahead, the landscape was hazy but the long shape of Jbel Tichchoukt thrust up, a rude gesture almost, putting us in our place with the 28 km we’d walk to just pass along its flank in a few days’ time. Walking over horizons eventually stopped fazing us.

We made Tizi Ouiridene, about 2000 m, and followed a good path down shale-covered strata to a stream in the corner where all six of us were glad to drink. We then descended brown slopes, freshly ploughed and being worked over by black wheatears, one of the ubiquitous birds of drier parts. For several days we’d seen what we called the Atlas redstart, a cocky bird of black, white and brick red clothing (Moussier’s redstart, Phoenicurus moussieri), which is only found in the Atlas Mountains.

Crossing a rise led us down to the well-scattered houses and fields of Tafadjight. Apples were growing in abundance but what made the place different from anywhere else were the houses, square in shape, with the north sides clad in cedar boards. From a distance, the effect looked like corrugated iron. Some of the more recent buildings were iron clad as the cedars are now officially protected. Balconies, complicated stairways and yards were all made of wood, however. A white mosque tower stood beside the souk but there wasn’t even one shop open. Angling along between the oddity of wire fence and a vertical drop to the river, the mules’ panniers made far too wide a load and Tamri was nearly bumped over the edge. Hosain therefore took down a post or two so they could walk along the field before returning to replace the fencing.

That huge hollow of life drained off into a deep gorge so we were forced up onto a stony piste which climbed high, away from the Oued Taferjit. The terrain was again uncompromising limestone, and, despite the warning of dervish-dancing clouds we went on strike after a shortcut over jagged rocks, bodies demanding food and liquid. As we hurried on up to regain the piste there was a dash of hail. The mules were sheltering below scrawny oaks waiting for us but as the hail continued to belt down and the thunder was cracking overhead, we donned full waterproofs. Our feet collected great dollops of mud as we slithered along the track. At the high point, Tizi Essous, the goo at least began to flow downhill. The mules were quite good at glissading on the mud which clung disgustingly to our boots.

Variant tracks were a bit worrying but we were never likely to be lost (head west and, perforce, we’d reach the Atlantic) but being temporarily mislaid was a nuisance and an admission that the machinations of the map had at last succeeded. We trampled short cuts among the fan palms or hopped along the spikes of weathered pink rock—anything to avoid the build-up of mud on our feet which would drag like a ball and chain, wobble us as on stilts and then collapse with a splodge like some pachydermatous excrement. Of all walking surfaces I find clawing mud the most revolting.

As to our destination, the general line was clear enough: the huge mass of the Tichchoukt bulked ahead, a sort of Schiehallion seen end-on, the cleft of our pass (thrice the length of Loch Rannoch), the southern bypass of the hill. There were obvious army posts of no great antiquity visible on strategic points below and we discovered later that was a borderland where Berber and French forces confronted each other. We learned that from a charming man who confirmed the path towards our next destination, Tilmirat. As we were speaking to him an old lady rushed over from the house with a silver salver bearing cups of tea. In minutes we found out that she had a son living in Taroudant, who was known to Ali. The end result was that she sold us a turkey which then rode on top of Taza for the rest of the day, frequently being swiped by passing branches as we went up and down and over an arid maquis with oak and juniper and scented rosemary, a cheery river in the gorge below, lined with the spears of tall poplars. The heat hugged the slopes and, despite the clawing jungle, I used the parasol. Tilmirat proved to be just a few houses below path level, a cluster of well-blessed farms where even the dogs couldn’t do more than lift heads to watch us pass. We descended another steep, harsh limestone slope towards a river.

There was an incredible complexity of rivers, meandering in sheer gorges before collecting together to become the broad Oued Maasser, soon called the Oued Sebou which flows on past Fes before reaching the Atlantic at Kenitra. We suddenly realised we had to cross this united flow. Where the path reached the bank the oued was wild so we fought the jungle upstream to a wider, but shallower, reach. We over-reacted, packing cameras away and taking off our trousers, and paddled across scarce up to our knees. However, it could have been the other way round, the water up to our necks, as the red, silty waters made a visual check on the depth impossible.

We camped on a terrace below olive trees, a seguia (irrigation ditch) beside us, and dined on fresh turkey served in a sweet onion sauce with bread brought to us by the owner of the idyllic spot. As so often happened, we were lulled to sleep by the music of the flowing river. Sun and water are the oldest gods of man.

Peyron gave dire warnings about what lay ahead, and Peyron is usually right. Any differences we noted were the result of seasonal changes. He passed that way after seven years of drought when things would certainly have looked different. The Atlas frequently suffers the manipulations of climatic extremes; but at least the Atlas has the saving grace of actually having seasons. Peyron’s distances and descriptions should be regarded but a note of caution needs to be sounded about the times he gives. He was a lean and fit individual, exploring the Atlas year in and year out at all seasons. The untrained, over-indulged office worker going straight from city life to Atlas trekking is all too likely to find a twelve-hour Peyron route a recipe for benightment. For our trip, whenever Peyron gave treks of 10–12 hours duration, we automatically planned to take two days instead. We also had to read Peyron’s descriptions backwards as his text runs west to east. His warnings of the complicated navigation in descending from the long Tichchoukt pass were quite justified. For most of our ascending we could make little of the map or Peyron. We’d also had the doubtful guidance of the old man on whose terrace we’d camped. (He is forgiven as he brought some vegetables, four eggs and bread as well as the misinformation.)

The afternoon before Ali had ridden over the wide Oued Maasser perched on Tamri’s rump, and the mule had not shown any concern for the big river. Come the morning, however, loaded and ready to go, he just would not cross the metre-wide seguia running above the terrace. All the considerable tricks of the trade from Ali and Hosain, from (literal) carrots to (literal) kicking, failed. They were determined Tamri would cross (“He has to learn!” an exasperated Ali explained), even to the extent of unloading the mule again. This made no difference but, for reasons of his own, he did eventually jump the tiny water channel as well as some invisible hedge about two metres high, landing metres beyond the imagined obstacle. This overkill—or over-jump—was an astonishing and entertaining spectacle. There are many seguias in the Atlas and only slowly did Tamri accept them for what they were and not treat them like a Grand National obstacle. Large rivers never bothered him at all. We began speculating what he’d do when faced with the Atlantic: probably treat the sea as a wider river and start off for the Canary Islands.

The maquis through which the mules were driven to find the promised good track was beginning to shred the tarpaulin covers and had also reduced progress to a dusty slowness, so when Ali saw a good mule track on the other side of the valley he opted to go right back down and find this. We’d meet at the valley head, Insh ’Allah. The valley on our side soon became a limestone scarp but a faint trail wended along the lip and eventually dipped into the red rocks of the gorge to end at an abandoned farm on the other bank, along which our mules had to come. We made the most of the water and washed top halves and bottom halves of our bodies in turn. A kestrel was working along the gorge and a chittering of choughs mingled with the stuttering of bee-eaters while the warm rocks were much favoured by brimstone butterflies. We were not long on the trail again when the mules caught up.

The valley bifurcated near its top, and still thinking we might reach the village of Mohammed Azeroual mentioned by Peyron, we took the left fork. Layers of cultivation kept forcing us higher and higher and suddenly we were above the tree-line, back in the freckled alpine world. Our gap to bypass Tichchoukt lay right ahead but the huge view was what really impressed all of us, and it takes something for Ali and Hosain to be impressed. We were beginning to worry about water, as Peyron indicated there was little or none on the day-long pass ahead. If we found some, should we carry an overnight supply? As soon as we voiced our concern we saw a source with a trough just below us so all six of us were soon drinking. While we ate bread and cheese with Cup-a-soups and coffee the mules made inroads on the fan palms, a diet which looked as nourishing as barbed wire. We set off again in the heavyweight heat, agreeing that we’d all stop up the pass at 1600, wherever that would be. We soon found ourselves on the edge of a deep hollow with no easy alternative but to go down over gritty disintegration. Being at the angle of minimal adhesion I had a good test of my sandals. Charles tried a couple of rolls and slides and used words I’d not heard from his lips before. We were led more and more across tiered acres of terraces and then forced up by a big house. We carefully tried not to intrude too much only to hear later that Ali and Hosain had stopped there for tea.

This ‘arid valley with no water’ (Peyron) proved to be so cultivated, right to the banks of the grey river of spate-boulders, that we were largely forced to walk along this pebbly riverbed. I suppose the track meant well but it was as tiresome as any pebble beach, only uphill. New houses were being built all along the valley, in quality stonework. The seesaw battle between man and rough nature always moves me in these circumstances. On the left flank of our ascent, the fields only ran up a few hundred metres, as far as a seguia could lead water from the stream coursing down the pebble walk. There were boxwoods and layered cliffs with the usual exuberance of choughs overhead. The new life delighted but I also wondered what would happen given another seven-year drought.

At 1530 we came on a newly cut andrair which would take all our tents together, and decided that was our site. A few minutes later the mules arrived. Hosain put a Melolin patch on Taza’s sore back and had another session of saddle-adjusting. We had turkey, of course, but the dried mushrooms I put on to soak beat explanation or translation until I fell back on drawing them.

Years ago at a poor village in the Agoundis valley, which we came down to after a traverse of the Tazaghart Plateau, a drawing proved useful in communications. Not knowing the Berber for eggs I drew one and squawked like a hen which not only gained the desired provisions but had the listeners raucous with laughter. Later, I wondered if the failure to imitate animal sounds tied in with the Islamic prohibition on drawing people and things. I seemed to spend the next hour going through my entire pets and farmyard animal sounds before a growing crowd of villagers of all ages. The kids doubled over holding their tummies in an agony of laughing. They insisted we stayed (little did we know) and the solitary grey rabbit that had been hopping among our feet was grabbed and carried off to be turned into rabbit tagine.

One of the first signs of affluence in a village is to install grilled windows, which have a conspicuous white margin painted round them. Coming off the hill we’d noted there was only one white window in this village, obviously poor, which was another reason we didn’t really want to stay. Four hungry climbers would be as harmful as locusts. We felt quite guilty about the rabbit. We were accommodated in the house with the one painted window and the bare room was given to us for the night. The day had been very hot and the mud-built house had absorbed heat over many hours so, when the temperature dropped, the effect was akin to having night-storage heaters, the heat radiating out again, not just to the starry sky, but into that small cell where we lay in our Y-fronts on top of sleeping bags and dripped in sleep-destroyed misery. Then we began to scratch. We began to scratch with the sort of crazed enthusiasm normally reserved for inescapable midge assaults. Our torch beams picked out the enemy—bugs, of scuttling, hairy repulsiveness, some cigar shaped, some round and flat, the latter being the airborne division for they crawled along the beams and then dropped on us. We built a wall of DDT powder round our Li-los and sat gibbering on those, watching the brutes wade through this defence which might as well have been caster sugar. We belted them as they came out of the cracks in the wall, we fought them on the floor, we fought them on our bedding and on our bodies, we fought them to the verge of sanity. It was a night to remember; only when the heat had dispersed and the frosts brought relief did we have a few hours of nightmare-ridden sleep. “Was it just a nightmare?” someone asked on waking. Then we saw the scores of purple blood blotches on walls and floor. It had been real enough. To reassure, that is the only such night we have ever experienced in the Atlas.

Years later, post DDT, I thought we might as well have some anti-insect powder for dusting sleeping bags, on the rare but annoying occasion when a flea came aboard. I happily went into my local Boots the Chemists and asked if they had flea powder. It was curious how the customers crowding round all took several steps back! I was told I needed the pet shop. Well, Bob Martin’s does excellently. For GTAM I thought it might be a good idea to carry hair-clippers. City barbers are expensive and we weren’t going to be in cities anyway while the incidence of ringworm and other nasties made the souk barber a doubtful option. Hairdressers at home gave up hand clippers long ago and I’d asked several before one gave the same answer, “Try the pet shop”. So somewhere along the GTAM I could hand the clippers to Charles and say: “Pretend I’m a poodle”.

Jbel Tichchoukt’s highest point may only have been 2794 m but it was an 18-km sprawl. Peyron warned that the western end peak was off-limits because of military installations but we took this to mean the peak’s summit, not the flanks which we traversed. Fortunately we passed on a Saturday while everyone was watching an important national football match on TV. We weren’t arrested.

We took a couple of hours to gain the high point of the long corridor flanking Tichchoukt. The stream shrank very slowly and the landmark of a solitary dying cedar never seemed to come nearer. The col itself bore the name Foum Bessene (Bessam), a wind-seared altiplano with a cemetery unlike any we’ve seen elsewhere. The graves were all cedar board coffins, now above ground level, the wood dry and shrunk and the contents long gone. A sad percentage of those strange coffins were miniatures. A small dry stone hut had a half tree trunk as a seat where we had a rest out of the bullying wind. There had been cultivation during the ascent, and for the following two hours we walked through new green pastures. The vegetation was lush enough for brilliant poppies, adonis and other weedy flowers. The next two hours didn’t appear to change the scenery, always the mark of big landscapes. New houses and a few grazing mules were the only signs of life. Our lunch stop was on another draughty watershed and we cringed by a ruin to eat oatcakes and Kiri cheese, feeling very small and immaterial, like a sweetie paper blowing along a promenade.

As we began to lose height the landscape became well watered, there was a confusion of new pistes and even signs of tractor ploughing. We found the correct path up to the county town of Boulemane and scored a big arrow and an H in the soil to indicate the route for Ali and Hosain. We passed an old oak with a vast girth that leaned crazily from the slope to give blessed shade. There were strong scents of box and juniper, the sweet and the tart, these plants seemingly enjoying the limestone slopes especially. Round a corner was a hidden cirque full of grazing flocks. A few trickles ran down before suddenly exploding into a huge flow with a strong resurgence. We marked some other path divergences up to a last pass from which a 3-km scarp-demarcated valley ran, steep and straight, down to Boulemane. A small saddle on this route held a cluster of military installations and oil drums. We tiptoed past and the mules came innocently after.

We paused just above the town at a source, almost afraid to cross a goudron (tarred road), the first we’d met since leaving Bab Bou Idir, being one of the great north—south routes from Fes to Midelt, the Tafilelt and the Sahara. The French had made Boulemane a garrison town, as a cemetery indicated, but traders, slavers and armies must have used the route over millennia. To the north and west lay a country scattered with many dayat (great bird-watching lakes) and the twin towns of Azron and Ifrane, built by the French in Alpine style with red-roofed chalets and palaces. In high summer, the government would retreat to these cooler hills just as the British would leave Delhi for Simla, a fantasy made sharper by seeing the cedars as deodars and the name Imouzzer-du-Kander on the Fes road came out as Kandahar. Hidden in the forest is a small ski resort, Mischliffen, where one of the tows operates on the inner slope of a volcanic vent. Years before, Charles and I had made a long ski tour over that landscape. Volcanic hills with snow was a strange combination and the unreality was made complete by having troops of Barbary apes trundling across our ski tracks. The P20 northwards goes through Sefrou (a neat and delightful town) before descending to the Saïss plain and Fes so Boulemane was once an important post on the royal Trik es Soltan trade route with the Sahara.

Thirst took us to Boulemane, down a pine-clad dell, to a cheerful café with a garden and tables shaded by gaudy umbrellas. The speaker was blaring out a tape of Andes music, which I recognised as one I’d bought from Peruvian strolling players in Warsaw! We had another coffee down in the square beside the mosque. There are no hotels in this busy market town and the tourist passes by; the very lack of pretension makes it interesting. We bought a load of vegetables and hot bread. Returning to the source we found Hosain waiting patiently. Ali eventually arrived with a small charette (barrow) with supplies. Taza and Tamri were glad to get stuck into some grain and straw. Their feeding is carefully regulated. Ali explained the details once but, never our concern, I’ve largely forgotten the facts although too much liquid and the wrong ordering of their food could have serious consequences. Mules, we were discovering, were as complex as motorcars. By Boulemane they were ready for servicing.

The owner of the terraces offered us an empty house but we liked the site so camped. It was strange to have the headlights from night lorries sweeping over the tents, lorries lit like Christmas trees with red and green lights. We were left to keep an eye on the tagine while Ali and Hosain vanished to the hammam. Hosain led us there later for our turn. The water went tepid but the room was still hot and steamy so our cleansing went well enough. We demolished the last of the turkey for supper.

Boulemane was supposed to be a rest day but we walked down the P20 to round the peak of Bou Beker and camp in a quiet valley rather than stay by the town. There were children about who were looking after a few grazing mules. They ‘helped’ us pitch tents, fetched water and were quite delightful. ‘Rest day’ meant we went mad washing every stitch of clothing, did some planning ahead, and much eating. Ali with a straw hat returned with a charette of fodder, and a shower had us rushing to rescue drying clothes. Ali dealt with half a chicken for supper. The other half hung nakedly on a hook from the apex of the tent like some weird votive offering. Planning wasn’t helped by our next day’s route not having a single name on the map.

Nor did much of the landscape agree with the map, but by teasing away at the navigational problems we eventually reached a long valley running south—southwest which led to the Tatyiywelt cultivations, at least mentioned by Peyron. Cows were standing knee-deep in a tarn. We had a day of bad encounters with dogs guarding isolated houses (a ski pole has its uses). Most dogs are being territorial but occasionally we ran into a pack roaming half-wild which were more threatening.

Tatyiywelt was a rare grassy site, coarsely woven and short in texture, with a seguia trickle meandering through. The flow was dirty but following up the course I found this was because the water had been run through a newly ploughed field, and not far above was a good source with water gushing out from a red sandstone gash. Having several 5-litre water bottles was useful on such occasions. Empty, they weighed little, and were tied onto the mule loads at the last minute where they would occasionally clonk against each other all day and drive the listener bonkers. If camping far from water Taza or Tamri were used to collect an overnight supply.

A cloud of about twenty ravens drifted over the site engaged in all manner of pair-bonding aerobatics. I saw the first cheery patch of Convolvulus sabaticus mauretanicus, so dark in colour as to be nearly navy blue. This is a well-behaved convolvulus species which forms a football-sized clump so is both a safe and colourful friend in my garden at home where it chums another blue flower we met the following day, the hedgehog broom (Erinacea anthyllis). Like many of the flowers thought to be rare in the Atlas, when you come on a flowering area there can be a profusion. I suspect a lot of botanists only go up one valley, find one place where, say Narcissus rupicola watieri grows, and declares this rare. However, had they gone up each valley along that particular range they would have found plenty, in every site with similar characteristics—and several apparently odd settings too. Watieri must be one of the most beautiful of all miniatures: a tiny pure white daffodil no wider than a 10p coin. This gem is so common in one area of the Atlas, that I once placed a bowl of them on the supper table and watched the botanists with me give the most violent double take. Plants have gone round the world as perhaps the greatest colonists of all. Fields in the Atlas are often hedged with prickly pear (Opuntia ficus-indica, often called ‘Barbary fig’), a cactus which Colombus brought from America. (In certain areas there are what appear to be other cacti but these are a classic example of parallel evolution being euphorbias, purely African.)

We had stopped early at Tatyiywelt to be sure of water. We were too cold in the wind to hang around so Charles and I wended off independently and, later, chanced to meet on the hill slopes above the head of the valley. We went on upwards to see what we could see. It proved to be a complex mountain with secretive hollows, some ploughed, but with hosts of startlingly dead old cedars. Grazing had destroyed much too but we noticed the centres of the topiary-like bushes (stunted trees) were sending out fresh stems since the goats were now forbidden. Some herds of sheep were meandering along the craggy slopes. The summit—Jbel Habbid—was still tree-covered at 2447 m. Only Jbel Habbou (2488 m) a few miles off was higher, our GTAM route being chosen partly to take it in. The view was a bit hazy, a winter wasteland. The sky was like Pyrex. A strange knobbly area of marble lay north: white and ghostly. As the wind was knocking us about we lost height quickly and were back at camp in time for tea. Women in gaudy garments came and collected their bony cows from the meadow. The tents impressed us with their silent stability in the wind; even over supper we could hear the endless reeling of larks overhead, one of the day’s consistencies.

Big winds usually are tailed by big wets and by the time we were abed (1930) the rain was smashing down—the sort of rain that would have Noah starting his round-up. I complained in my log, ‘Two weeks, all unsettled so far’. Conditions became very cold and I was periodically aware of thunder, and of movement and voices from the Discovery end of the site. Some clattering of teapots suggested they were having a midnight brew.

Dawn hadn’t so much broken as done a poor job of putting itself together again, and we discovered what a horrendous night the others had endured. We found Taza and Tamri swaddled in the blue tarpaulins and the lads asleep with exhaustion. Their night had largely gone fighting to save the mules. Taza had had her covering blown over her head, had gone down and been unable to rise, and young Tamri was in a pathetic state. In the tearing rain, sleet and snow (“It cried tears of snow”, Ali told us) the mules had been fighting to stay alive. Sky-stabbing Tichchoukt was a white beacon and the snow greywashed the flanks of the valley beside us. Life was as unsmiling as a late Rembrandt self-portrait. We demolished coffee and jam sandwiches while Ali played his Irish tin whistle to cheer us up.

Just over a small col we came on the Lerkcheb huts as Peyron calls them, an occupied homestead with penned sheep set, like the Cheviot trig point, in a great goo of mud. We plodded past on a minor piste, new lines scoring in many directions, part of the effort being made to restore life to the forest. There was one big farm where seven mules were grazing on a meadow bright with buttercups and romulea. The inadequate map had us navigating carefully. Over one col we saw a steaming mud flat which helpfully pin-pointed a supposed lake on the map, and we hit the right track to head up and over the rolling, snowy watershed. We were given some bread and cheese, oranges and biscuits off the mules and they pushed on for kindlier levels leaving us to go off to climb Jbel Habbou. Climbing the highest peak in the area simplified navigation; at least one spot was certain. (There was a shattered trig on top.) In that unsettled weather we had to grab chances—‘Our now/Which is all the place/We can ever be’. The whole area was covered in dead trees and, down again, we followed our mules’ tracks over another long valley-cumplateau that slowly tilted to a conical hill, Lalla Mimouna, beyond which we had told Ali they’d find our objective, the forestry hut of Aghbalou l’Arbi.

This stark maison forestière suddenly appeared over a green boggy meadow, red-roofed, with storks nesting on top and a line of poplars beyond. The setting would not have been out of place in Dr Zhivago. Morocco has such quantities of space, and variety, that it has been used for many film locations: The Young Winston, Kundun, Hideous Kinky, Harem, Jewel of the Nile, Othello, Jesus of Nazareth, The Sheltering Sky, Sodom and Gomorrah, Lawrence of Arabia, The Man Who Would Be King, Gladiator, Babel and Kingdom of Heaven are some I can recall.

Hosain came out to greet us; the mules had been stabled and tea was ready. Ali had used his charms on the forester and we were to stay. Tails of rain were soon swishing across the big screen. Ali kneaded out a basinful of dough as there was a fancy gas oven but after an hour of failing to make the contraption work, despite, or because of all the helpers, the resident old lady took away the big circular lumps to bake them in a fire. Pulled apart, hot with butter and honey, they were delicious. Bread is broken, not cut, because it is holy. When Ali spilt some flour he carefully brushed it off the floor so nobody would step on it, because it is the symbol of life. Later, noticing he still had two pairs of trouser on, I was told that this kept the inner ones clean for when he wanted to say his prayers.

We had a very sociable supper with the boss’s son (the forester had gone off) and others of the family: a chicken tagine with a huge rice pudding with plenty of milk, butter, eggs and raisins in it and a nutmeg for flavouring. The locals added salt to theirs, sweet rice not being something they’d met before. The lanky, loquacious forester with his robber baron moustache joined us for coffee and was appalled at our planning to sleep on the floor. He opened up a room of his own house, which had a kitsch clock among lots of votive candles and natural history specimens. We were shown the map in his office with the optimistic forestry plans. Like all the foresters we met he seemed delighted with and proud of his work. Apart from the line of streamside poplars there were no trees anywhere near the house. A solar panel powered enough light to read as we sprawled on comfortable mattresses listening to the rain outside.

We discovered the effect of the socialising at 0500, when I found the door was locked and although we had a key on our side we also required an Allen key-shaped handle, which was missing. We tried a variety of substitutes from penknife to ice axe ferrule without effect. In desperation, we opened the shutters and knelt on the sill to pee into the night. At six I was wide-awake so, failing on the door again, climbed out the window and went for a walk. The neighbourhood dog was friendly. An old lady, seen far off in a black and white shawl, materialised as a stork. People consider it very lucky to have a stork nesting on the roof. When one bird flies in to join its mate on the nest they both throw up their heads in a loud beak-rattling ceremony. These Concordes of the air are often seen circling in the thermals. Old nests can be built up to over two metres high and while the storks occupy the penthouse suite, a dozen noisy sparrow families occupy the flats below.

As I could not climb back into our room (the window was too high) I eventually roused Ali and Hosain by banging on the shutters of their room. They found a handle somewhere else and freed Charles. Obviously there had been a very sociable night, part of which was ensuring we were well out of it. We tramped off across a plain to an obvious tizi in the hills beyond, and in that time a brilliant sunrise had turned to grey and cold. We really were becoming fed up with the endless poor weather. We took Peyron’s 1½ hours to the Tizi n’ Taddat and had a muddy descent to the Aquelmoun n’ Sidi Ali, a substantial lake among the Beni Mguild’s tribal pastures not far off the main Fes—Midelt—Tafilelt road, a spot often visited by ornithologists. On a previous May visit I’d noted marbled teal, ruddy shelduck, spotless starlings, pratincole, red kite, serin, shorelark, and several wheatears and plovers. For GTAM, the water shivered coldly and all the birds were black dots far offshore. Buzzards mewed overhead and there was a gossamer drift of lark song as we picked our way through huge flocks of sheep to the huge, derelict European-style building that was once a hotel. The only colour came from the erratic flight of a blue damselfly. Nobody was fishing for trout or char that day.

We found a spot out of the wind and all too soon picked out the blue dots of the mules coming down from the tizi. The lads were for pushing on and Ali was in a glum mood, which could have been partly the result of the late night. He complained the mules were starving, Tamri’s back was sore again and Taza was limping on the rear starboard side. Hey ho!

We followed the lakeshore and passed a smaller lake, a water-filled crater. The sand was black and we had to pick a way through a whole array of jagged volcanic debris. We were edging along a wide strath where immense flocks of sheep were grazing. Nomad encampments were tucked in odd corners and seemed to be made of bits of wood and plastic sheeting. We paused for a somewhat subdued bread and cheese lunch. Eventually we stopped on a meadow by the Tizi Moudmam which we made 2130 m. The Col du Zad, the highest point of the P21 road to the south (2177 m), lay just a kilometre away. An old man guarding a donkey couldn’t fathom what we were doing. He reiterated, “Tourists have cars”. Several men were using the ubiquitous mattock to dig up the skinny roots of something like a parsnip but I only got a Berber name. The root is obviously a treat as I’ve seen it on sale at souks for a high price. Eventually Ali and Hosain went over to the road to hitch south to Zeïda in search of fodder for the mules.

Zeïda is largely a place of roadside cafés where the Marrakech road breaks off and wanders west between forested hills to the north and the huge Melwiya plains to the south, with a horizon of snowy peaks (Jbel Ayachi, Jbel Masker). We’d be cutting across new hill country to cross this road and the Melwiya plains to reach Aghbala, our next big staging post. There were a few surprises before Aghbala however.

The greatest traveller of all time came this way in the fourteenth century, criss-crossing the Atlas Mountains. Ibn Battuta (1304–77) was a Tangier Berber who set out in 1325 to make the pilgrimage to Mecca, journeying via Egypt, Syria, Iraq and Khuzistan. He then really began to travel, visiting East Africa, Constantinople, Caucasia, the Hindu Kush and India where he remained for some years serving the sultan of Delhi. He was sent on a lavish embassy to China but suffered shipwreck and disgrace. A second embassy succeeded however and he travelled to and from China via Sumatra and Ceylon. He escaped the Black Death in Syria and visited Moorish Spain. He’d been away twenty-four years! His story was dictated to the sultan’s secretary in Fes and then he was dispatched across the desert (Sahara means desert), to visit Mali, Timbuktu and the lands of the River Niger. His journey back from the Tafilet by this Trik es Soltan was made through blizzards worse than any he’d met in Afghanistan. On the way he stayed with the brother of a merchant he’d met in China.

Ali arrived back in a cheerier mood from Zeïda and the mules snuffled into their food. To ensure fair rations, Tamri was given a new, decorative nosebag. Much of my time at this tizi camp was spent over Peyron and the maps, the former all too brief and continually using names that didn’t appear on a more than usually confusing map. His west—east description reads:

‘After the Kerrouchen outpost, forest trails go into some of the most thickly wooded areas of the Atlas; a matchless combination of rolling hills, stately cedars, grassy glades and murmuring streams, with Barbary apes galloping through the trees. Bivouac by the banks of the Oued Srou near Miwraghen Forestry hut. A gradual climb past wooden-roofed Timzought village onto the soggy, bird-haunted reaches of Luta n’ Zad and from there to the Zad Pass and the main road.’

A longer French version of his guidebook gave more names and times so we worked out our theoretical route and had an ETA for Aghbala in five days rather than the 3–4 of Peyron. There were plenty of dots on the map to indicate human habitation, inferring water and supplies if required. Kerrouchen sounded like a minor town. The major Oued Serou could hardly be missed, nor the Marrakech road, and Ali had a tongue in his head! Pas de problème.

We still found it strange to hear the growl of traffic coming up to the pass in the night. There must have been a souk not too distant since on the Tizi Moudmam mules were coming in from all directions and being fed or tethered or, in one case, cavorting loose and raiding every other beast’s food so there was much kicking and pursuing by the guardien, while the owners crowded into a minibus and trundled off. The tizi was the watershed and when our cavalcade arrived we left the Trik es Soltan and angled down to pick up a bold line of lakes shown on the map, a country which was lush and quite different from any we’d traversed. There seemed to be a super-abundance of water and the farms were large, with plenty of cedar boards in evidence, and pitched roofs which are seldom seen elsewhere. The first lake had shrunk to a mud patch and we swung along a big watercourse bordering a green vale, with regularly spaced farms. We could have been in the Tyrol, except for the battalions of cedar trees drawn up on the slopes on either side.

Tamri suddenly collapsed. His load had to be taken off and then put back. Ali said he was having trouble urinating and he had unsightly piles too, not a happy animal. Taza was still limping, from an inflamed tendon. We then became ‘mislaid’. Our valley path should have taken us past a second lake and then round a hill to yet another. We found neither and could make no sense of the map but what we did find was a secretive hollow with a tidy village of pitched roofs, flag flying over the school and singing girls taking the cows out to graze. (In less lush areas they keep the cows at home and send the girls out to graze.) That place was not on the map either. Away to the left lay a huge area of green landscape which was no doubt Peyron’s Louta n’ Zad. There was a graveyard on one hill that we passed, ringed with sky blue flax flowers. The graves had proper markers and the knoll was defended by a fence. Often graveyards are barely noticed, with individual graves just a slight hump with, at best, a boulder at the head or foot, often overgrown, not being grazed by sheep or goats (of which the country has an estimated 30 million).

A cheery lad on a mule joined us for several kilometres in the required direction for Timzought, one name we could give being both on the map and in Peyron. We crossed a piste and our friend went off singing after handing us on like a many-legged parcel to a second man on a mule who said he’d be happy to go with us and also give us accommodation. He lived just below Timzought. “Did we want?” As the morning sky had been swamped with bog-cotton clouds and the first shards of rain were falling, yes, we wanted.

Our route led down a long spur between the Oued Zad and the Oued Serou and even the steadily-increasing rain couldn’t detract from the beauty of the area: the slopes surged with cedars and an interweave of fields. Our host-to-be rode ahead, hunched into his djellaba, a dark shape below the pointed hood like some Tolkien figure. We slid and slithered after, enjoying a variety of colourful muds. The predominant colour was brick red, complementing the rich greens of the cedars. Even with waterproof tops, bottoms and brolly the wet began its insidious entry. The mules were soaked of course.

Down on the Zad side a pair of storks was perched on top of a solitary dead tree, like one of those religious fanatics on top of their pillar. Another big cedar was smoking among its branches from a fire which had burned right up inside the trunk. Enjoyment gradually oozed out of us. The rain seemed to be gutting the landscape. Our host never looked back. The down, down went on forever, and we were hot and sweaty in our protective gear. A village appeared. Hopes rose, and fell. Ali and Hosain drove the mules down skittering red mud and slabs on the edge of a gorge. At the foot Tamri played up at crossing the infant Oued Zad (here joining the Oued Serou) and refused a seguia beyond. A stiff pull up once across had me gasping and I stopped for a vital drink of water. Dehydration in a deluge was an irony I’d happily go without. A glutinous switchback followed. We dropped down to the river again, wedeling in the mud, but there our host came to life and indicated a farm perched above as being our desired haven. We plunged into the river to wash off the mud and squelched up to the house with the thunder banging overhead. If the initial four or five kilometres had proved four or five miles at least they had not turned into four or five hours. Time and distance are very European concepts.

Taza and Tamri were given straw in a barn then we sprawled in the guest room. Day old brown and white kids tiptoed in with us while we sat at the usual low table, painted with vivid geometrical patterns. A huge dresser filled the end of the room. Was it built in situ, I wondered. Scrumptious hot bread came with the welcome mint tea. There was a deluge awhile and then it just rained for the rest of the day. The snug house was roofed with huge lengths of cedarwood, still stippled with adze marks, and several wigwams of boards formed shelters for the oven, woodstore and anything else. A hollow trunk formed a trough. Later, when only drizzling, a girl went out to chop wood. She was thoroughly competent and handled her axe the way her British sister would have handled a doll. (In the Atlas, dolls are usually baby sisters who are wrapped on the back and are raced, jostled and hop-scotched without complaint.) The farm’s goats had some shelter but the sheep were just penned in a ring of thorn bushes, being woolly and waterproof. I suppose human skins are waterproof too but there’s a designer fault over our insulation efficiency.

The whole of one wall in the room was taken up with a loom on which a blanket was being woven, a hideous striped, Barbara Cartland pink colour. After the tea we all slumped on the cushions and snoozed but before the light failed I roused to write up some notes and try and make sense of our map and prospects for the next day. Not too far down the Oued Serou there was a bridge and a piste to Kerrouchen which was a name beginning to take on a kind of mystical significance. We began to hope the town might have a hammam. We demolished a roasted chicken and a mutton tagine with heaps of fresh bread, oranges and coffee. We had to have a chaperon for our late night pee call and the damned dog barked at ghosts for much of the night.

Our host gave us a discouraging forecast too—from their TV. Television is now a reality in some extraordinary places in the Atlas and the influence, as ever, is both good and bad. It can be manipulative but programmes on healthcare, improving drinking water supplies or agricultural advice probably balance appallingly bad Western movies or unending Egyptian soaps. The forecasts take no ultimate authority though and will end with Insh ’Allah, a let-out which the BBC might envy.

Nobody was very lively on waking. The morning mists were fingering a tapestry through the cedars and the sky was black and threatening. Surely not more bad weather? ‘For heaven’s sake! This is late spring in the Atlas!’ I wrote angrily in my log: ‘Wonky mules, manky weather, woeful walkers.’ We were given ineffectual directions and at the village downstream, which could have been a group of alpine chalets with the cedar slopes above, we were hailed by a man who offered us kebabs—of ‘pig’. They had apparently shot an ilf (wild boar) and were loathe to waste the meat, always something of a luxury. The man later attached himself to Ali and Hosain to become the unlucky charm of the day. Charles and I shook him off and then went astray in the forest as paths led us higher and higher before disappearing. The forest was magnificent but sprawled on a 45° slope of limited adhesion. By the time we’d slithered along and down to the Oued Serou we were at the road bridge, or bridges, for a new goudron crossed on a better bridge beside the old and wended up into the forested slopes. Before the sweat could dry on our backs the cavalry caught up. They’d met up with a party of Barbary apes so we doubly damned our diversion. I’d first met these monkeys (they are not apes but a species of macaque, Macaca sylvanus) when bird watching above Azrou. I was watching a nuthatch, a rarity to a North Brit, when there was a thump of something hitting the ground—and there was a Barbary ape having a good scratch just 20 metres away.

These are the same species as the well-known collection on the Rock of Gibraltar, which are on the army pay roll and whose presence on the Rock is indicative of the continuing British possession. If the apes go, so will the British. The irrepressible Tristam Jones (one-legged sea dog supreme and author of several autobiographical escapades) tells a yarn of how he made use of this by fixing a good price with the Algeciras police for kidnapping some of the apes. He sailed across the bay and a few days later returned with a haul of apes of all ages—a severe dent in the Rock’s population. Well paid, he sailed on for Suez, noting Algeciras was yet another port he’d best not visit in future. They might just have found out that the ape population on the Rock was unchanged. He had sailed over to Morocco and purchased the apes there.

A couple of heavy motorbikes roared over the Oued Serou bridge; we could hear their din as they zigzagged up to the north. They were backed-up by vehicle support, a considerable overkill for such easy going. We agreed to meet up with Ali and Hosain in Kerrouchen. Our self-appointed helper knew a saddler there and he’d give us a room, which sounded perfect. Taza’s saddle could be re-modelled and we’d have a roof if there was more rain. We ambled on pleasantly, writing a cursive route through the forest, up and up. We doubled round Jbel Tabarine, which we might have avoided had the map been clearer, but were however rewarded by the finest area of cedars of the whole trip: huge 300-year-old trees in park-like grandeur with much natural regeneration and areas of recent planting. Not for the first time we were impressed with the efforts being made to preserve this glorious asset. Looking back, the early weeks of the Traverse had two indelible memories—the Beauty and the Beast if you like—the richness of the cedar country and the continuous uncongenial weather. But eventually Beauty kissed the Beast did she not? Surely, some day, the sun would shine as the sun should.

The descent was on a piste, ready for the tar to go down. Shepherds clustered round a fire in the raw air. To save time, we cut off a big bend and wended down through the trees. A drizzle began and we realised we were astray again or rather that we could not fit in the reality with the map’s imaginative delineation. We teased away at navigating (Charles’s altimeter a useful aid) and were eventually sure again: there were motorbike tracks overprinted by boots and mule tracks. We cut more corners and came out of the gingerbread forest into wheat fields and grazings. We could see Kerrouchen. The sun shone—for that fraction of the day at least.

The sun soon grilled us and we had to take a rest and drink. The fields were edged with tassel hyacinths, tiny purple irises, poppies, rock roses, lupins and camomile. The piste became wickedly stony. We began to dream of a café in Kerrouchen, which sat on a compact ridge, topped by a mosque tower, and backed by a bruised, black sky that promised a thump of rain. We walked on what looked like man-made pavement awhile but was simply level sandstone strata. A kilometre before the town we came on the others. The saddlemaker seemed to have been a chimera and Ali wanted to avoid the hassles of bureaucracy so we were led off down fields and farms, well-watered and with good camping spots, to skirt below the town. We walked off the rim of the world into a jungle of oak scrub just as the thunderstorm split the curling clouds. Our ‘help’ said he knew a farm, and then got us all completely lost. He had light shoes and no waterproof gear or any belongings. “All mouth and no brain”, was Hosain’s concise observation. In a Terry Pratchet phraseology we had ‘the sort of storm that suggests the whole sky had swallowed a diuretic’. The ground wasn’t just wet, the whole surface was gushing water, a red flow that sizzled like a fire and tore whole banks apart to carry off earth and stones to the Oued Serou far below. The scrub tore at our clothes and ripped the covers on our baggage. We felt like we were loping through lasagne decorated with holly, becoming thoroughly depressed. So much for the comforts of Kerrouchen!

We found one farm (by chance) but they couldn’t or wouldn’t help. Taza was limping badly again but Tamri had more sense than baulk at a torrent of red water that we had to cross. This soaking was quite unnecessary as it was obviously going to rain at the time we caught up but I was beyond anger. A girl fetching water from a well at a second farm wouldn’t take us in either as there was no man present and, for all she knew, we were kif smugglers or worse. However, she said we could camp in a nearby area of sparse trees and beaten soil. The rain eased long enough to rush up the kitchen dome tent and we excavated platforms and dug drainage ditches before erecting our personal tents. Ice axes make good trenching tools.

When I laid my ice axe momentarily on a hump of sandstone I did a double take for there on the rock was a small cluster of ‘cup marks’. I let out a yell of excitement that had voices query if I was OK. I was thrilled, for these mysterious prehistoric carvings are distributed down the Atlantic coastline from the UK to Portugal and Spain but this was extending the range into Africa, so my excitement was justified. I’ve since come on them again in the far Western Atlas (Flillis), near Tinerhir, south of the mountains and on Yagour.

I forgave much for that serendipitous ending to the day but not to the extent of tolerating our unwanted guest any longer. He was sent packing. His presence had already delayed supper and our tin of turkey didn’t disguise the flavour of burnt vegetables.

We went to our own tents with the rain still dancing on the roofs and puddles. In the morning we were able to dry out, the camp tree dangling sets of waterproofs as if there had been a mass hanging. The sun god obliged with horizontal shafts of light that picked out features in unnatural brilliance, delightful while it lasted. The man of the farm had returned so came over and had to be entertained awhile. We drew water from the well, lowering a rubber bucket (recycled motor tyre) on the end of a hairy rope, hand over hand. Ali went over to the farm and returned saying there were ‘bad people’ about and we’d best leave. As we left he was giggling and I asked what the joke was. “In my sleepy state this morning I tried to light the stove with a Knorr cube box instead of the matches.”

The road on was a corkscrewing in and out and up and up before plunging down to a new goudron (a road into Kerrouchen from the Khenifra side). The cloying hamri (red soil) constantly built-up under our boots so progress was purgatorial. Charcoal burners were sending up smoke signals. Oleanders in the eroded gullies indicated a drier climate was normal and the fields, as usual, were bright with flowers. Among the many tassel hyacinths, I spotted one of the strange brown-flowered ‘bluebells’ (Dipcadi seritinum). We had almost descended north to the Oued Serou again, while we really wanted to cross the long, rising flanks to the south to reach the Moulouya plain and Aghbala where, come hell or high water (or both) we would stay in the town and have a day off.

We tackled the slopes from a scattered but affluent-looking village with a big school, the village as red as the soil it was made from. The southwest gables of the houses were defended from the rain by overlapping layers of oleander branches. Pitched roofs were still the norm although, after that day, there were no more. Only in a few corners of the Western Atlas was there anything comparable. Architecture is never static. Leafing through the books of the early Victorian embassies to the court of Morocco there are many illustrations of what look like simple grass huts, rather like wigwams, but I have never ever seen one.

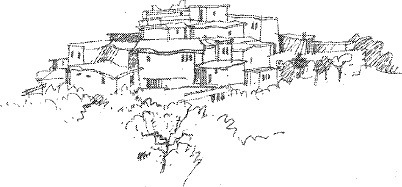

What is very attractive today is the way, even in new towns, a distinctive style of building is adhered to. This creates a harmony we have lost in Britain. History comes into this of course. In the past, rural life was so uncertain that a crude hut was ambitious enough when there was no guarantee of taking in the next harvest or surviving the next harka (raid). Architects are expendable in survival situations! Climate helps too. Open courtyards, high balconies and arched terraces don’t really go with our home weather. We, of necessity, enclose, look inwards and draw curtains. There, air and space are part of the scheme and the kind sun allows an orange tree or fountain in the court and walls bolstered with a shock of bougainvillea. There’s a simple elegance that even opulence doesn’t destroy; palaces are just such places on a larger scale and using finer craftsmen and more extravagant materials.

Such musings were soon forsaken. If clinging hamri mud was bad enough in descent we squelched and scrabbled and stumbled up endless field edges, periodically falling off our stilts of goo or angrily banging our boots on the stones to be rid of the tiresome weight. Rounding a spur we found we were looking down on an intermediate valley of great lushness. A woman, unasked, gave us a big round loaf of bread, hot from the oven, and refused any payment. We paused to eat it, with spiced sardines and Kiri. A nightingale sat on a fig tree a couple of metres overhead, throat throbbing out the variable music.

We planned to angle up to a col beside a bump which was given a spot height; I wanted a check from Charles’s altimeter. But no Charles arrived. There had been a fork where Ali had built one of his thin homme des pierres and scratched an arrow on the path but Charles had walked past the signs. First Hosain and then Ali went off to try and retrieve the stray. Hosain and I traversed some fields to be more visible and eventually Ali and Charles joined us. The lack of a check led to a real mix up. We were aiming for a village, Arrougou, and, despite nobody about to confirm directions, we assumed Ali knew where we were going. Zigzags led to a hamlet I assumed was Arrougou, but the cavalcade went on and on and up and up, in a biting wind, crazily off course. When a figure was encountered Ali went to check and merrily led us downhill again. We lost hundreds of metres in height which we had to come up again the next day.

Fields and oakwood gave way to a steep glen into a bigger valley. Some moussem (festival) had obviously been held at the confluence as, from there, we were swept on in a flow of people, as if borne along in a home-going crowd after a football match. The valley was dominated by a huge scarp (not on the map) and two dots of houses (on the map), forming a compact village around a central square. A big water channel led us to it. So much for our easy half-day. The best we could do for accommodation was a couple of cell-like empty shops opening onto the public square, one for Taza and Tamri, the other for the four of us who slept as packed as puppies. The cells had the musty smell one associates with old French books.

When Ali was being shown the stables the door collapsed onto an old man so we had to plaster his shaven head. This led to a general first aid session, not that we could do much for the many goitres in evidence. A gusting wind made us pleased not to be in the tents. The village swarmed with children, the boys football daft but not at all camera shy and the girls with bright dresses and brighter smiles which vanished anywhere near the camera. There was no loo of course but I did not regret the early walk out of the village. The elder bush I hid behind had a nightingale going full throttle, in competition with blackbird, chaffinch, the ubiquitous cuckoo and a whole squabble of sparrows. Knowing the route only too well we set off long before the mules were ready, accompanied by some children keen to practice their French. One pointed out his little brother as “mon soeur”. The cuckoo was still calling—kou-kuk they called it. On being told there were plenty of sanglier (wild boar) I asked if they shot them. A thoughtless “Oui” was at once given an over-ruling “Non” and the child received a lecture from big brother during which I heard the universal word “police”. Well, poaching is the third oldest profession in the world.

Just beyond our high point of the day we cringed beside a well of icy water to wait for the mules. Girls came up from a hamlet to fill water jars and a solitary man in a red selham (cloak) rode down on a mule, muffled up against the cruel wind. The clouds were skimming overhead, but the landscape of the Oued Serou was also patterned with dark oakwoods, viridian fields, red soils and golden stitches of sun. Someday I’d like to follow the river all the way from source to plains, as the river runs through magnificent country and the navigation would be so simple.

The mules went storming past and we had to yell to stop them on the col. The Tizi Mouchentour was a mere dip in the crest, where cloying mud had me again swopping sandals for boots. Charles and I boulder-hopped field edges up to the wreck of a trig point at 1933 m. Windy or not, larks were singing in the grey. Pity there was no far views for big hills are hoisted on the horizon. I took a while to work out our onward route and we found the mules grazing a moist valley bottom, glad that they’d paused to ensure we were all heading onto the big plains together. From a rise we could see the road from Zeïda to Marrakech, an old, familiar route. A small douar (hamlet) beside it had a miniscule ‘shop’.

These little hanuts have increased in the last decade but the stock can be limited and not necessarily on the correct side of a use-by date. However, wormy biscuits and oxidised sardines are no longer the norm and, joy to us, remote spots are likely to have some brand of coca. In one village I once wanted to replenish candles and asked for bougies. With a twinkle in his eye the shopkeeper handed us a packet of spark plugs. As there was no road, within half a day’s walk this seemed an unlikely product to have in stock. (Bougie is both candle and spark plug in French.) GTAM had taken in, or would take in, several weekly souks by intent and we never ran out of supplies, but burning up energy at our rate any topping-up of sweets, biscuits, chocolate or drinks was welcomed. I am sure we came to know every brand of confectionery in the country.

Crossing the road we walked over the next horizon to Azerzou where we stopped on a grassy bank below the stark houses to picnic. A stork had set up home on a lamp with the light shining down into the nest: all mod cons. A good piste led us on and the day was suddenly intensely hot. Huge cumulus clouds boiled up over the plains. Our cavalcade appeared as tiny dots miles ahead to give the landscape scale and reassure us as to a common choice of route. A moving house-sized mass of brushwood materialised into a poor over-laden donkey. For a kilometre, the verges were domed with my favourite sky-blue convolvulus then a rise gave us the first true view of the vast scale of the Moulouya plain: east and west it ran as far as we could see. The map, incorrectly, gave another Azerzou below our perch. We caught up the mules by the grey flow of the Oued Moulouya, the longest (400 km) Mediterranean-bound river and the boundary between Middle and High Atlas ranges. Tamri slipped in the mud and went down so both mule and all our gear was given a coating of greywash. An over-hasty loading led to the gear soon tipping off again and to a sore rubbing on Tamri’s back. The oued was patently undrinkable but a youth said there was good grass and a well on the other side. The oued was wide enough for Tamri to cross without objection. We humans paddled.

Jbel Masker and Jbel Ayachi bound the plain to the south, their snow-covered flanks visible. Ayachi to the Berbers is the ‘mother of the waters’ and was first climbed by an outsider in 1901, de Segonzac, one of the early explorer surveyors of the French penetration from the northeast borders. But Ayachi was almost certainly mentioned by Herodotus (400 BC) and loomed mightily for a Roman general (AD 42), Ibn Battuta (14th Century) and others on the Trik es Soltan. Its snowy bulk was once thought to be the highest peak in the Atlas. Early maps often put Mount Atlas against Ayachi but they also speculatively put Mount Atlas to the south of Marrakech or towards the western end, locations where snowy peaks could be seen from city or sea. The secret of the highest would be kept for centuries. Charles, Ali, a friend Len and I traversed all the summits of Ayachi in 1992, being chased off by the mother of all thunderstorms. We also climbed Jbel Masker. These, backing our view south that day, are of such longitudinal scale that they extend over the horizon to both the east and west.

Midelt, then Jbel Ayachi, was the start of a notable Willison journey in 1983. In some ways, the town of Midelt marks the eastern end of the main Atlas, but we wanted to extend our route further to take in the new Middle Atlas country. John Willison was an army officer and hit on the idea of an independent Atlas traverse. His route often differed from ours, or Peyron’s GTAM, though both Peyron and he stopped (or started) at the Marrakech—Agadir road. Willison stated: ‘after that only the purist would walk finally to Agadir’. The logic of this starting/finishing point eludes me. We never considered anything other than reaching the sea; after all the mountains do so! Accompanying Willison was ‘a young lady of sporting inclinations but no great walking experience’. Four people commenced but, not for the first or last time, coping with Jbel Ayachi took its toll and the others fell out. With inadequate maps, no Atlas experience and a punishing summer season John and Clare Wardle had quite a rough time but, again and again, praised the kindness and hospitality met along the way. (A few years later John was killed in the Alps but his father has kindly let me quote from his journal.)

The Melwiya only irrigates a narrow swathe in this wide barren wilderness, the course marked by slim trees, lit like torches along the banks. The well was an oil drum set nearly flush with the grass but from the depths came pure, clear water. We had the tents up in a flash and a brew on when an old man came down from a nearby farm with mint tea and bread with olive oil. Ali had been rather reluctant to make contact. We’ll never fully understand all the ins and outs of social life. They are a very complex people with family breeding, religious affiliations and wealth and official status all playing a part. A whisky-swilling Shereef (descendant of the prophet) with the lowest of employment may be given an esteem we’d find surprising but I’m sure a Moroccan would find the nuances of British etiquette equally baffling.

Behind us, the Middle Atlas was covered by a black pall so there was a feeling of thankfulness to be over Moulouya or Melwiya, which is how it is pronounced. (Foucauld had Mlouïa.) Our first three weeks or about 400 km looked quite substantial when seen on a road map of Morocco. Even illiterate Hosain was impressed. With the crossing of the Moulouya we were really done with the Middle Atlas, the area we’d known least.

I was pleased that, despite all the difficulties, we were a day ahead of our schedule—but the picture could change once into the mountains again. Beyond Imilchil we had long days at altitude and there would have been snow, not rain. I teased away at logistics, sprawled on the grass until a pitter-patter of rain sent us inside, destroying our hopes of a day when it forgot to rain. An explosive sunset burned golden behind the supplicating upreach of riverside poplars. Out of the north came the complaint of thunder. ‘How long, oh Lord, how long?’ I wrote then lit a candle and wrote for an escapist hour or two. In the morning when I shook the flysheet to spray off the raindrops I found they were clinging beads of ice. The sky was the colour of a clear mint.

Charles and I followed the Oued Moulouya for two hours, marking any junctions with arrows, but the mules still went a variant route. A small shop produced drinks and Taggers. The hanut was topping-up its stock; like a West Highland village store it didn’t have much of anything but something of everything. Inadvertently I dropped the plastic snake and the large crowd of kids round the door vanished as if vapourised. There were far more paths than the map showed and we were dithering over the route when a young-looking female spoke to us—in English. She was from Rabat and was one of the local teachers. Sadly we turned down an offer of tea and, at the next ford in the oued, luckily chanced on our companions. The obvious peak of Toujjet to the south, which we’d half-planned to climb, never seemed to come level with us and there was another two hours of sun-tramping to reach another recognisable map feature, a side stream, the Oued Guelgou. Here we left the pistes, determined to cut along more directly. We also discovered a small gap between two of my photocopied maps which didn’t help to bring horizons any closer. We lunched on an arid knoll. Hosain produced a forgotten radio and, perched on Taza’s load, broadcast western or Moroccan/Egyptian pop to the empty world. We let the mules on ahead.

We had been gaining height steadily all day and the oasis feeling of the river shrank away for a splendid aridity. The mountains grew closer, and the huge cauldron-boiling cumulus grew blacker. We touched the Arghbala goudron (tarred road) briefly but walked a parallel mule track rather than a road which was spoiled by ugly power poles. This tilted plain held the upper sources of the Moulouya and ended in oak-covered crests beyond which lay Arghbala. The peaks of Toujjet and Ariba cringed below a textbook thunderstorm: the black cloud trailed long streamers of rain and the lightning flashed regularly. We quickened our pace but the tail of the storm caught us, racing in at an audible canter. A few minutes later the world was deafened and drenched by the downpour. As we could not travel quicker than the flashes we said Irish ’Allah and plodded on. Wearing Berghaus ‘Lightning’ jackets seemed all too appropriate. A strange monument was passed and I could only guess at a French creation marking some past battle. They were rather keen on them. We swung towards the goudron and a break over the rocky crest, keen now to walk a firm surface for our boots were heavy again with the instant mud. A steep pull up set the thighs screaming at the effort then we went downhill, downstream, into Aghbala of the Aït Sokhman.

The higher town had one-time French barrack blocks and there were other tiled roofs in the lower town. Being the day before the weekly souk, plastic café-tents were going up. On other days the souk area doubled as football ground. The main street was like a river and at the first café Ali dived into the insalubrious interior while we stood and dripped along with Taza and Tamri. Ali squelched back and suggested we stayed there while the mules could be stabled elsewhere. We would have agreed to anything in that discourteous wet.

Our quarters were through the spartan café (which nevertheless sported a picture of the king) and up unfinished stairs to a big concrete area with breeze-block walls. A smelly loo under the stairs and animal quarters below added a rustic atmosphere. Seedy or not, the presence of a light bulb in a nest of dodgy wiring was a luxury. We’d camp there well enough. As ever, from quite unpromising sources came food that was excellent. There was even central heating in the form of a converted oil drum, a not uncommon feature in remote places and surprisingly efficient. When Charles, Ali and I had been chased off Jbel Ayachi, a house in the remote valley to the south lit one of these stoves and with no more than half a dozen lumps of wood had the top glowing red hot so our saturated clothes dried overnight. While Hosain and Ali went off with the mules to find stabling we ordered coffee and demolished baguettes and strawberry jam. Later we sat on an upstairs café balcony in the centre of the town to watch life go on, rain or not. Being so utterly non-touristy a town, we were either ignored or given friendly greetings; there was not one “Bon jour monsieur, un dirham”.

The unseasonable bad weather was worrying, for me at least, for I knew the mountains ahead and was already presuming that, beyond Imilchil, our planned high-level route would be impossible and a major diversion would have to be made either south or north—which might take us off the maps we possessed. I could spend the next day on logistics while a saddler was making a new outfit for Tamri. The poor beast was rubbed sore in several places. Reddish-brown djellabas seemed to be the Aghbala fashion and our café filled with as ruffian-like a crew as could be imagined: swarthy faces and bandit moustaches, exotic garb, a ready-made cast for a pirate movie. Even after all those years I find a touch of the unreal when such characters prove to be kindly, generous folk.

We took our last coffees upstairs: the roof leaked, the byre smelt, our tents (hung up to dry) dripped, the breeze blocks crumbled. Another stray man put down his bedding but was shortly scandalised by Charles’s night performance which sent Ali into a fit of the giggles. Our roost may have been a dump but was dry, well dry-ish and we felt quite at home. Daybreak brought some leaking but we had a busy day. As well as a new saddle for Tamri, we had to sew up a failed zip on the big tent, buy a new basin and stock up with food supplies. Charles and I made a brief recce for the following day’s departure and came back to the ‘Aghbala Hilton’ with built-up red mudsoles. The barometer was well down and by mid-morning the streets were rivers of ‘redwash’ again. When we bedded we were subjected to a timpani concerto of drips landing on dixies, pots, lids and anything else that could catch water. With minor orchestration, a modern composer could have conned us into believing we heard music. The wail of weather died out in the night, probably from exhaustion.

Sleep came with the sound of the indestructible female voice of Oum Kalthoum whom I first heard in her native Egypt fifty years ago. She died in 1975, but her tapes just keep selling and selling, far beyond numbers ever dreamed of by our painted posers in the west. This cruiser-weight figure with grey hair tied in a bun, singing to strict traditions, has outsold The Beatles. Colonel Gadaffi postponed his coup so as not to interrupt a charity concert she was giving for the PLO.

Wednesday was Aghbala’s souk day and while Ali and Hosain and the mules took off over the first hills we went, like iron filings, to its magnetic pull. The walled area was filled with scrawny livestock and we were thankful we didn’t have to buy local mules. The large number of women taking part was unusual and I don’t think I’ve ever seen so many lorries at a souk. The women all wore the Central Atlas striped handira, a blanket wrap-around. Every souk has its own character but the practicalities are the same, simply being an outdoor hypermarket, selling meat (slaughtered on site), fruit and vegetables, oil, poultry, bread, spices, nuts/dates/figs, eggs, salt, mint, sjinj (doughnuts), new and used clothing and footwear, household goods, pottery, floor-covering/carpets, radios and cassette players, tools and windows. There are also services: cobblers, barbers, restaurants, repairers of radios, etc., while more luxury goods or gift items are available according to the area’s affluence. There will be itinerant minstrels, cookie sellers and Berber jewellery touts.

Few tourists I’m sure ever see this particular souk. We received brief nods or were ignored but I caught the word Roumi meaning foreigner (the Highland equivalent would be Sassenach). This word has roots in the word Roma (Rome) which indicates the country’s long independence and resistance to outsiders. The word Nazrani is more specifically anti-Christian yet the Berbers themselves were largely Christian before Islam arrived. (Tertullian, Cyprianus and St Augustine were all Berbers.) Quite how the three ‘Religions of the Book’ rub along is an ever-shifting and complex matter; the said books can be quoted to justify almost anything.

The souk area was tacky with the mire, but was nothing compared to the traverse along the slope across the valley. There were times we could barely move for the mud which had been well-churned by mules heading to the souk. A litter of floppy dogs greeted us on the col and swallows were skimming through, heading north. “They should have more sense,” Charles commented.