Berlin in the 1970s was cavernous, its empty buildings echoing the voices, politics, and gunfire of a tumultuous twentieth century. In 1919 the Weimar National Assembly effectively replaced the German empire with a parliamentary republic, empowering the capital Berlin with democratic heft; its population doubled in one year to nearly four million. The seat of the Third Reich two decades later, Berlin was the epicenter of both Germany’s growth and its military conscription. As such, it was also a desperate battlefield by the close of the war, enduring 363 bombing raids, each blasting away more of the city’s nineteenth-century architecture. From a peak of four and a half million inhabitants at the start of 1943, Berlin’s population dropped well below three million by the war’s end. Many were killed or left homeless; others simply retreated to the safer countryside. Fully half of Berlin’s buildings were damaged or destroyed.

The division of Berlin in 1949 into East (under the military occupation of the Soviet Union) and West (occupied by American, French, and English forces) was a traumatic schism: Berlin would be a microcosm of the Cold War that followed, one foot in the communist DDR and the other under the Allied Control Council in alliance with the Bundesrepublik. To stop the illegal escape of East Germans to the west, the DDR cordoned off West Berlin with the Berlin Wall in 1961, effectively silencing any exchange between the city’s halves. Immediately felt as a toxic presence, the wall drove businesses and families away from the neighborhoods it cut through, particularly leaving the borough of Kreuzberg a ghost town. On both sides of the wall rose facelessly blocky and functional modern buildings—neubauten, as they were called. But rather than replace dilapidated structures, they mostly stood amidst the ruins of both grand old buildings and hastily erected edifices from the Nazi boom, rising above the smattering of foreign military encampments.

By the late 1960s, students in West Berlin—children of the war generation—had become increasingly radical in their leftist politics as they witnessed and participated in the rise of anti-establishment hippie culture, including rock music and drug use. Growing up in a state that mandated a social remorse for the war and the Holocaust induced both shame for the previous generation’s complicit cowardice and more generally suspicion toward traditional values and aesthetics. Housing was cheap because old buildings were plentiful—this was a city of three million built for five million—so it was easy for young people to gather en masse, incubating and reinforcing their sentiments into real political stances. An economic recession, the Vietnam War, insufficient support for students, and eventually the attempted assassination of Rudi Dutschke, a young leftist leader critical of government hypocrisy, led to an organized youth uprising and riots in April 1968. These actions were taken in solidarity with similar movements in the United States, England, the Netherlands, and especially France, and they left the city tense, divided now by generation as well as geography. Militant leftist organizations such as Andreas Baader and Ulrike Meinhof’s Red Army Faction became infamous forces of political change.

When a new cast of students came to the graffiti-covered West Berlin in the 1970s, it had tempered only slightly from the Situationist-inspired riots of 1968, but now the reputation of its reappropriated landscape and idealist politics ensured the blossoming of artistic scenes, new fire amidst the old rubble. In a mismanaged attempted at rubbing the DDR’s nose in the artistic opulence of a free society, the Bundesrepublik enticed these creative youths to come to the city, promising financial assistance and—perhaps most important—exemption from military service. As teens and twentysomethings gathered, they turned welfare distribution centers and student administration offices into subcultural hangouts.

Beyond that, as if wandering a dérive of Berlin’s ruins emptied by the war, these students declared squatting the natural response to a city on the edge of nowhere, and they formally organized the first squatting communes in late 1971, beginning on Mariannenplatz in Kreuzberg. Hartwig Schierbaum, who would later front the synthpop band Alphaville, came to Berlin in 1976. He says, “It was like an island out of this planet. It was a terrible thing, this monster, but at that time it was where you just could escape reality.”1 For those teens and twenty-somethings, the economic reality of the city helped to ferment both heavy drug use and ideological experimentation. Schierbaum continues:

It was inexpensive. It was free. You actually didn’t have to care too much for a living, because there were so many subventions, so much money being putting in. It was the spearhead of western ideology in the heart of the communist empire. So actually nobody in Berlin at that time really worked very hard. There was no reason. You could just go there and just live there without doing too much for it.2

As the 1970s crept on, this experience would become well known through books such as Christiane F.’s wildly popular heroin autobiography Wir Kinder vom Bahnhof Zoo and films such as Werner Herzog’s ultrableak Stroszek. To adventurous musicians and artists, West Berlin was acquiring a reputation. Certainly the fruitful residency of hipster gods David Bowie, Brian Eno, and Iggy Pop in 1977 didn’t hurt this perception; Bowie’s proto-postpunk Low and Heroes albums were respectively mixed and recorded at Kreuzberg’s Hansa Studio by the Wall.

Musical community, as posited by the popular music scholar Will Straw, “presumes a population group whose composition is relatively stable … and whose involvement in music takes the form of an ongoing exploration of one or more musical idioms said to be rooted within a geographically specific historical heritage,” whereas a scene, “in contrast, is that cultural space in which a range of musical practices coexist, interacting with each other … work[ing] to disrupt [historical] continuities, to cosmopolitanize and relativize them.”3 More than any other industrial crèche, Berlin in the 1970s had a vibrant experimental scene that was greater than the sum of its inhabitants’ creative and social output. This makes a bit more sense when we look at how ever-shifting casts of young artists lived and created at the time.

At any moment in the late 1970s, 150 unlawfully occupied squats operated in West Berlin, mostly in or near Kreuzberg. Just south of the Spree River and separated by the wall from the East Berlin borough of Friedrichshain, Kreuzberg was an impoverished, ugly part of Berlin. Those who lived there were generally vagrants, students, or Turkish immigrants who had come to Germany for postwar work rebuilding the country. Young anarchists and socialists took over entire streets and parks in the corners of West Berlin. Any given squat would house between eight and fifty people, either living rent-free or paying a low lease, sometimes attending the Berlin State School of Fine Arts or the Technical University, but fundamentally acting on anti-establishment rage. The numbers were too great for the police to control: phone trees powered by hacked communication lines enabled these young people to assemble by the thousand within an hour. The organizational soundness of the culture afforded an artistic scene complete with cafes (the Rote Harfe was a favorite), discos, and makeshift libraries. Berlin’s constantly changing cast didn’t impede the microcosm’s day-to-day life, but instead, change was built into the scene’s basic operation. Indeed, a student’s political shift or a change of drug habits might mean moving from, say, Albertstrasse 86 to Wienerstrasse 25. Some squats were ideologically dogmatic; others offered nonstop partying.

For Berlin’s young artists, rejecting tradition and old values meant that formal training and craft were no longer requisite or even desirable—an idea that also inspired the punk movement in England. Because of this, the experimental nature of the early films by Christoph Döring and Yana Yo, recordings by Einstürzende Neubauten and Die Tödliche Doris, and paintings by Kiddy Citny all testify to these artists’ learning by doing. Their work, in all its visceral directness, therefore gives us a relatively unfiltered view of its makers’ remarkably consistent desires.

Consider the trope of destruction as a means of escape within the West Berlin art scene. 3302 Taxi is a 1979 short film by Döring that puts viewers in the driver’s seat of a car that repeatedly accelerates head-on toward sections of the Berlin Wall. The presumed collisions are themselves unseen, and although the most banal explanation is that actually driving into the wall would have been logistically prohibitive, a more artful interpretation is that whether the wall breaks down or the driver is killed doesn’t actually matter: both are alternatives to a life confined.

Other Berlin short films reinforce the destruction-as-escape theme. In Horst Markgraf and Rolf S. Wolkenstein’s 1983 Craex Apart, an intense, wordless actor (“Ogar”—no relation to the Skinny Puppy singer) simply pounds huge logs, pipes, and sledgehammers on the interior of an abandoned room. Yana Yo’s 1982 Sax reverently follows a procession of three young saxophonists (members of the punk act Nachdenkliche Wehrpflichtige) through the disused innards of a Berlin factory to its rooftop, from which they then faithfully leap. The destruction either of the self or the other disrupts the static binary: Berliner and Berlin, new and old, man and machine. It’s a pessimistic twist on the Futurist fascination with the crash explored in Chapter 1.

And so when we turn to the early work of Einstürzende Neubauten, the most radical and enduring of the early German industrial acts, it’s easy in this context to understand their place within a Berlin scene hell-bent on literally clashing with the surrounding cityscape. In the squatters’ street battles against local authorities, “People started to build barricades and they drummed for hours on the metal fences and barricades,” lead singer Blixa Bargeld (born Hans Christian Emmerich) explains, “and [ours] was fundamentally the same music.”4 For example, the “Stahlversion” B-side of the 1980 single “Für den Untergang” was recorded in the empty steel interior of a highway overpass: literally enclosed by the functional architecture of the city, percussionist N. U. Unruh (born Andrew Chudy) banged out rhythms with concrete blocks on the metal floor. Similarly, their later music video for “Der Tod ist ein Dandy” concludes with the image of a sledgehammer beating a hole through a wall (the wall?), revealing ever more inescapable city beyond the city.

The pounding and banging that Einstürzende Neubauten is known for wasn’t just the behavior of a band stuck in Berlin, but the presence of Berlin in their blood, inasmuch as the city’s understaffed police, secret slums, and slacker population readily encouraged drug use. Band member FM Einheit recalls, “Taking speed was a way of life. This of course influenced our recordings. Being as crazy as one is on speed can only be achieved by actually taking speed.”5 Speed is an antisocial, antisensual drug that builds up mental and muscular tension and demands that its user release that tension immediately and aggressively. The constant themes of extreme physical exertion and obliteration in West Berlin’s film and records likely both fueled and were fueled by amphetamine usage. There is arguably also a political dimension to the city’s speed trade: it’s true that Nazi soldiers were given amphetamines as performance enhancers, but more significantly, the amount of drug use among youth in the city in a similarly circular manner both reflected and contributed to West Berlin’s aggregate psychological condition—a disillusionment no doubt framed as normative by its isolation from the rest of West Germany.6 As Schierbaum recalls, “There was lots, especially the heavy drugs like heroin and that kind of shit.”7 He continues, anecdotally connecting this with an urban politics of negation, “When you’re in the drug scene you’re really confronted with the more direct possibilities of human behavior. This just led to my having a very deep disbelief in political movements.”8

Einstürzende Neubauten’s relationship to their surroundings is highlighted by their choice to sing in German—a decision that their West Berlin scene contemporaries shared. By and large, German, Belgian, and Dutch popular culture had been infatuated with singing in English since the 1960s, and when Anglophone punk music and journalism reached continental Europe, the cachet it carried meant that singing in German could actively brand a young act anti-cool by continental standards.* But Einstürzende Neubauten and their scenemates effectively rejected geographically external standards, and in doing so they managed to address directly the condition of being where they were. Crucially, singing in German meant rediscovering and reclaiming German-ness. To the parents of this young generation, Anglophone music had offered a way to silence the uncomfortable questions of German identity after their own unforgivable complicity under Hitler. Making German music here and now in Hitler’s capital thus did the vital work of breaking that silence and fulfilling every rebel’s longing to cut loose once and for all from parents, teachers, and bosses, to burst free from the past’s quietly tightening stranglehold on the present. It’s a kind of détournement that industrial music invokes again and again: by embracing the forbidden, one rejects the original behavior that inspired the fear of taboo.

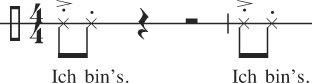

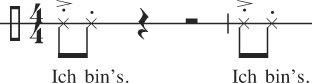

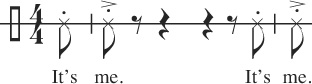

There’s something about the German language itself that was important, too—the way its rhythmic mechanics shape a song’s delivery. German’s predominance of strong-weak vowel patterns (trochees) means that lyrical phrases often start on musical downbeats, and its decidedly un-English, raspy, fricative consonants make for a certain level of mouth noise in singing. In German, a song like Einstürzende Neubauten’s “Ich Bin’s” (which means “It’s Me”) repeatedly hits the word “ich” on a musical downbeat, scraping the Teutonic “ch” suddenly against a pounding ictus, then delivering the weaker, staccato “bins” an eighth-note later, the afterthought of a collision in time.

Singing the title lyric “it’s me” in English would mean aligning the melodiously smooth “me” with the downbeat, ambiguously trailing off, with “it’s” having come before the downbeat. This not only ruins the rhythmic surprise of the lyric’s arrival but turns the song from a march into a gallop.

All this helps to explain the common belief among industrial musicians and fans that Germany as a technological, political presence in history and that German as a spoken language together resonate uniquely with industrial music’s penchant for technological and tragic themes and its rhythmic, timbral aggression. This belief extends well beyond Berlin, and even beyond Germany’s borders: America’s Stromkern, Italy’s Pankow, Slovenia’s Laibach, and France’s Die Form, in addition to taking Germanic names, have all chosen on occasion to sing in German. Similarly, the name of DRP, Japan’s first EBM band (formed in 1983), stood for Deutsche Reiche Patent. As SPK’s Graham Revell once said “I’m shouting quite a lot in German because I like the language—it’s a little fetish of mine.”10 The idea of nation runs through industrial identity, and in this regard Germany holds a privileged role.*

Einstürzende Neubauten was only one permutation of artists within the city’s scene. They regularly shared club gigs with new wave, electronic, and punk acts such as Mania D., Frieder Butzmann, Din A Testbild, Sprung aus den Wolken, Sentimentale Jugend, and the ferocious Nina Hagen, a rare East German emigrée in West Berlin. But beyond that, all these acts shared band members with near-promiscuous turnover, collaborated across media, and released recordings on one another’s makeshift tape labels—for example, Kiddy Citny, a Berlin Wall muralist and member of Sprung aus den Wolken, ran the influential small-run imprint Das Cassetten Combinat from 1980 to 1983, the year the squats were finally evicted. This social fluidity in the scene may have been as responsible for the aesthetic overlap between its participants as any preconceived ideology; like no other city, Berlin and its postpunk zeitgeist were a feedback loop of cause and effect.

Part of Will Straw’s definition of musical scenes stipulates their artistic cross-pollination and its dismantling of traditions and historical narratives. Though the interactions of artists in the city didn’t exactly give rise to a willful third mind in the Burroughs-Gysin sense, the variety of artistic media and politics that interacted calcified the need for young artists to tear down everything old. Whether witnessed in the 1983 film by Notorische Reflexe that projects footage of car burning and rioting in West Berlin onto a pulsing kick drum head or in Bargeld’s declaration that “all traces of the past are abandoned: only out of destruction can something really new be created,” the calamitous mandate for innovation was not merely an intellectual dalliance with modernism, but a vital social response to real desperation.12 And of course poor students in West Berlin had little to lose by destroying so much: one impetus behind Einstürzende Neubauten’s banging on metal for percussion was Unruh’s having sold his drums to pay rent in December 1980. Poverty was desperate; a photo of Bargeld’s apartment at the time again shows conflict with his surroundings. “Half evicted” from it, in his words, there is a collection of trash, noisemaking junk, and secondhand clothes strewn about. The word DILDO is spraypainted on a concrete wall, underlined.13

Central to but not synonymous with the West Berlin scene of the era was the loose collective of fifty or so people that ringleader artist Wolfgang Müller and Blixa Bargeld called Die Geniale Dilletanten [sic]—the ingenious dilettantes. The idea evolved from projects including a used clothing store (Eisengrau, created in 1979 by Gudrun Gut and Bettina Köster, who designed fashion and who later handed its management over to Bargeld), Müller’s fanzine, and ultimately a massive antirealist festival on September 4, 1981, with fourteen hundred attendees at the Berlin Tempodrom. Müller proclaimed a kinship with Dada and its trickster tactics, evident in the oddly placed near-humor of his band Die Tödliche Doris and in his 1982 book on the Dilletanten, which proclaims, “to find the unknown, one must take joy in playing the lustful game that goes with extreme pain.”14 This mix of joy and pain extended throughout the Dilletanten: artist Dimitri Hegemann went on to organize both the industrial 1982 Berlin Atonal festival and later the legendary techno-driven annual Love Parade in Berlin. In its sense of nothing to lose, Berlin in the 1970s and early 1980s routinely draws comparison with the flapper free-for-all of Germany’s Weimar era.

But with only the dimmest, most obsessive hint of glee, it was Einstürzende Neubauten’s frantic desperation and ritualized demolition that ultimately instilled actual fear and shock in audiences, earning the band a more immediate and lasting reputation with listeners than other members of the Berlin scene. With less of a division between popular styles and subcultural crowds than other western cities, West Berlin’s audiences and record stores—Zensor on Belgizer Strasse was the best one—conflated punk, noise, disco, and industrial musics into one scene, and so it was rare in playing to the city’s well-versed crowds that any band managed to do more than preach to the converted. But by 1981, when their lineup and instrumentation took a decidedly unmusical turn, Einstürzende Neubauten bore a darkness: their jackhammers, fires, hatchets, and broken glass were religious signifiers in their apocalyptic imagery. Indeed, their motto in 1980 had been “two years to the apocalypse.” At the Geniale Dilletanten festival, Bargeld declared, “it is now time of the decline, the end of time, definitely. It goes on for 3 or 4 years and then it is over. … I’m dancing for the decline, I’m not against it. I’d like it as soon as possible.”15 Demand for the band’s performances elsewhere in Germany began to set them apart from the Dilletanten and the rest of the Berlin scene, but their roots in the bleak architecture and pan-disciplinary makeup of the city were clear: on October 27, 1981, they embarked on a set of fifteen concerts around West Germany with Sprung aus den Wolken and the gothic new wave act MDK that they billed as the Berliner Krankheit—the Berlin sickness tour.

Einstürzende Neubauten’s story and music extend well past this short era. As Mark Chung recalls, by 1984 “we began thinking of ourselves as musicians primarily,” and indeed that was when the group’s members were able to go “full-time” in their work.16 In particular, their Concerto for Voice and Machinery performance at London’s Institute of Contemporary Arts on January 3, 1984, was a legendary bit of venue destruction, and their excursions into theater, video, and dance could constitute a legacy of their own were they not overshadowed by a long line of excellent albums in the 1980s, 1990s, and beyond. However, as far as industrial music at large is concerned, the focus given to Berlin in this chapter can help us understand more specifically the ground-level situation and some of the motivations from which people created this thing we call industrial music.

West Berlin was claimed by the government in Bonn, but given no voting representation; it was where companies claimed to relocate so they could grab government subventions, but they only opened shill offices; it was where students enrolled in universities but never attended; it was where new buildings arose while bombed ruins were never swept away. All in all, centralized administration, depressed commerce, and Germany’s own history played the role of absentee landlord to the youth of West Berlin, a city that was itself squatting in a neglected pocket of Europe. Authority, whether the government, the police, the universities, or the gun-wielding phantom limb of East Germany, could not be trusted. Even the ’68ers who had taught this generation how to riot were branded as out-of-touch hippies, all this to say nothing of the French, English, and American troops who patrolled the city, interchangeable and anonymous, ostensibly the good guys. Control was thus everywhere and nowhere at once. The trace of Burroughs’s paranoia in this conflation of power serves to emphasize the cut-up city skyline; as Tobias Rapp writes of Berlin’s youth culture, “the misappropriation of old buildings had been one of the most visible features,” whether real in the squats or fantasized in the willed collapse of new buildings.17 West Berlin offered a drug-fed dystopian pastiche that gave real urban echoes to a techno-ambivalent spirit of the age.

Reunified today, Berlin is increasingly gentrified, all the way to the slums east of the divide. When the wall was torn down in 1989, its most opulent graffiti-covered slabs, painted by Thierry Noir and Kiddy Citny of Die Geniale Dilletanten, were carted away and auctioned off in Monaco without the artists’ consent. Even as the traces of early industrial music’s Berlin disappear into a moderate twenty-first century, its recordings replay a rare memory of a unique urban moment.

It’s worth mentioning at this point that there were important developments in early industrial music elsewhere in West Germany (even if their relationship to a specific urban geography may not be as clear as Berlin’s contributions). Some acts, such as Frankfurt’s abstract noise group P16.D4, were isolated, almost anomalous. However, most of Germany’s industrially tinged music beyond Berlin was happening in Hamburg and Düsseldorf.

Alfred Hilsberg, a journalist for Sounds magazine, launched the shoestring label ZickZack in Hamburg in 1979, releasing records mostly by German electronic and punk acts—styles that, as mentioned, were functionally less divided in Germany than elsewhere at the time. Hilsberg, as singer Mona Mur recalls, “was this kind of weird drunken historian, living with his parents in a flat, releasing music from people from pretty much all over Germany.”18 ZickZack’s first release was the “Computerstaat” single by Abwärts, from whom Einstürzende Neubauten shortly afterward poached members Mark Chung and FM Einheit. ZickZack would also release music by postpunkers Palais Schaumburg, Hamburg-based proto-goths X-Mal Deutschland, and Düsseldorf’s seminal industrial band Die Krupps, formed by ex-members of the band Male (“Germany’s first proper punk band,” according to a Die Krupps album sleeve).19

In December 1980, Die Krupps recorded the basis of their Stahlwerksymphonie, and then refined the work in late March 1981 at the studios of krautrock legends Can. Under the direction of local punker Peter Hein (lead singer of Fehlfarben) the band created two fourteen-minute pieces, each built on the same lumbering dance groove of bass and drums, but layered throughout with clattering on what frontman Jürgen Engler called “environmental instruments,” being whatever scraps of metal and plastic they could assemble on site.20 The heaviness and reverberation of the drums resemble dub reggae in no small amount, and amidst the recordings’ tuneless guitar squawks Eva Gössling’s saxophone reminds us, like Clock DVA’s first albums, of free jazz pioneer Ornette Coleman’s place in the family tree of experimental pop at the turn of the decade. Later in 1981, ZickZack put out Die Krupps’ unabashedly Marxist single “Wahre Arbeit—Wahrer Lohn” (“True Work—True Wage”), which recast their metal banging within a synth-driven pop frenzy. As with so much industrial music, the song emphasizes the connection between body and machine. Its lyrics (in the band’s own translation) are:

All my muscles work machine-like

Steely tendons, sweat like oil

Dirt and filth are real labour

Pain and blame reward the toil

Pay—Labour

Given the song’s lyrics, it’s prophetic that the band was not properly paid for the record, despite it becoming an outright hit at Düsseldorf’s hippest clubs such as Der Ratinger Hof and Match Moore, and eventually across Germany’s youth culture. Mona Mur says of Hilsberg, “He wouldn’t pay the printing factory, he wouldn’t pay anyone.”21 To this day, there is a “rumour that ZickZack invested Die Krupps’ hefty ‘Wahre Arbeit’ royalties into its new stars, Einstürzende Neubauten’s first record.”22

With “Wahre Arbeit—Wahrer Lohn,” Die Krupps joined an increasing number of midbudget acts who used eight- or sixteen-step sequencers to create rigidly timed (“quantized”) pulsing synth-based loops. The basic approach of creating a two-measure bassline and playing it over a fast beat (with either real percussion or a drum machine) offered a lot of reward for its limited effort. With vocals sung none-too-melodically through an echobox, this was more or less the musical template for what would become Electronic Body Music.

Fellow Düsseldorf act Der Plan had a striking influence on Die Krupps, and eventually on electronic pop worldwide, although in their productive early days from 1978 to 1980 only a few appreciated their pioneering oddball synthpop. The band’s friend and eventual member Kurt Dahlke set up Ata Tak records to release their work (and that of his own post-disco project Pyrolator), but much of the original lineup found greater success elsewhere. Der Plan’s Chrislo Haas had a big hit in this step-sequenced style with his act Liaisons Dangereuses and their 1981 single “Los Niños del Parque,” and along with Der Plan bandmate Robert Görl he founded Deutsche-Amerikanische Freundschaft.

Deutsche-Amerikanische Freundschaft is perhaps the band most closely associated with this sequenced sound, despite initially focusing on improvisational noise music (again with saxophone). Despite the band’s name, no Americans were involved: the name is taken ironically “from local posters depicting rosy German-US relations.”23 Deutsche-Amerikanische Freundschaft’s first flirtations with sequenced dance music came on their minor hits from 1980, “Co Co Pino” and the superb “Kebab-Träume,” but much of their full-length album from that year, Die Kleine und die Böse, retained the experimentation and expansive, slow-moving textures of their more ponderous debut (also on Ata Tak). They temporarily moved to London, and after a few months of extreme poverty and tough luck in the squats the band was reduced to singer Gabriel “Gabi” Delgado-López and drummer/synth programmer Robert Görl. This duo, inspired by the UK’s burgeoning synthpop trend, would become Deutsche-Amerikanische Freundschaft’s most famous incarnation, beginning with 1981’s Alles Ist Gut. The album was produced by Conny Plank, who‘d helmed records by Kraftwerk, Can, Neu! and Ultravox, and it featured effectively nothing more than repeating patterns on an ARP Avatar synthesizer, Görl’s unchangingly fortissimo live drums, and Delgado-López’s tensely stilted voice, singing low in oddly accented German—he came from Cordoba, Spain, and at the time was barely conversant in German. Deutsche-Amerikanische Freundschaft had a lot of emptiness to fill both sonically and spatially onstage. The duo achieved this through a sheer kinetic aggression that might have come across as archetypically punk if the band’s image had not been so buzz-cut, muscle-bound, and hairy-chested—attributes they were happy to show off on album covers. The band thus appealed simultaneously to a European gay market ready to move beyond the disco of the 1970s and to straight-up punks who heard in them a similarity to the French aggro pioneers Metal Urbain—all while retaining the avant-garde contingent who had followed their early, arrhythmic sound collages. A common appeal for these audiences in Deutsche-Amerikanische Freundschaft was their irreverence: the biggest hit on Alles Ist Gut was “Der Mussolini,” which barked orders to shake your hips, move your ass, dance the “Mussolini,” the “Adolf Hitler,” and the “Jesus Christ.” The album went on to receive the Deutsche Phono-Akademie’s Schallplattenpreis.

Like Throbbing Gristle’s 20 Jazz Funk Greats album, the shift of both Die Krupps and Deutsche-Amerikanische Freundschaft to synthetic dance styles marks an important connection between noise-based, heady, “pure” industrial and the electronic, rhythmic music that has predominated public understanding of the term.

The popularity of Deutsche-Amerikanische Freundschaft and the electronic dance sound they were starting to share with Die Krupps extended beyond any ancestral industrial scene. The independent hits from Germany’s synth-driven underground were making money and receiving attention abroad, especially in the UK, where in 1980 alone the New Musical Express named German songs “Single of the Week” three times.24 For a brief moment in the underground scenes of Germany, fans, musicians, and independent distributors felt a yearning optimism that the day’s constellation of new musical styles—the Neue Deutsche Welle or New German Wave—would bring wider audiences to innovative music. Singles like No More’s “Suicide Commando” balanced attractively between the Berlin scene’s darkness and the blasé silliness of Der Plan. Ultimately, though, wide commercial popularity remained beyond the reach of artists who had shaped West Germany’s experimental and industrial awaking between 1978 and 1981, Deutsche-Amerikanische Freundschaft’s record deal with Virgin notwithstanding. Mona Mur worked at the independent music distributor Rip Off at the time. As she tells the story:

Everyone worked there—Mufti [FM Einheit] from Neubauten, Mark Chung. We would take the records, put them in huge packages, and carry them to the other stores. And it went well until 1981 when someone from EMI knocked on the door, saying, “Oh who are you? I just want to have a look at what track you are on.” We mistook him for some vacuum cleaner salesman and said we don’t need any. Bye bye. Half a year later the whole thing was bankrupt. The industry took over this energy, this [Neue Deutsche Welle]. They took the brand. Nena was number one on the US charts [with “99 Luftballons”]. That was a really bitter pill, let me tell you. … There was a small amount of time when we thought we could change the world and change the record industry.

ICONIC:

Deutsche-Amerikanische Freundschaft – “Kebab-Träume” (1980)

Die Krupps – “Wahre Arbeit—Wahrer Lohn” (1981)

Einstürzende Neubauten – “Armenia” (1983)

Einstürzende Neubauten – “Kollaps” (1981)

Liaisons Dangereuses – “Los Niños Del Parque” (1981)

ARCANE:

Borsig – “Hiroshima” (1982)

Die Tödliche Doris – “Tanz Im Quadrat” (1981)

Din A Testbild – “No Repeat” (1980)

Mona Mur – “My Lie” (1982)

No More – “Suicide Commando” (1981)