“There were seven hills of Rome, and seven hills in Athens. Well, San Francisco has seven hills too. Topography affects your mentality; it gets reflected in a mental topography. Living here makes you think big,” says V. Vale, subcultural archivist and founder of RE/Search Publications.1 The left coast city’s big thinking extends from the high-tech empire of Silicon Valley at the south end of San Francisco Bay to the hotbed of liberal politics in Berkeley, fifty miles north. Vivid and loud, arts in the Bay Area have buzzed perpetually for a century with the work of poets, publishers, artists, and performers whose collective ingenuity paints San Francisco’s history as daring, even reckless. At the height of flower power, it was a world capital of psychedelic rock and LSD manufacturing, and as Hunter S. Thompson put it, “There was madness in any direction, at any hour. If not across the Bay, then up the Golden Gate or down 101 to Los Altos or La Honda. … You could strike sparks anywhere.”2

Because of its tradition of experimentation, San Francisco gave rise to industrial music that broadcasts a dialogue between present and past, between the angry 1970s and the decades that came before. In stark contrast to West Berlin’s year zero and northern England’s response to working-class banality, California-based musicians, artists, and publishers such as Chrome, Monte Cazazza, Z’EV, Survival Research Laboratories, Factrix, and RE/Search Publications collectively engage with the memory of time and place.

The transition out of the 1960s and into the industrial is heard with the simplest continuity in the music of Chrome. Founder and drummer Damon Edge (born Thomas Wisse) was old enough to have been a hippie himself, and as he explained in 1980, “I’m not into projecting negative crap. We’re into positives. We’re not Devo. Dig?”3 In 1976, Edge and three bandmates had recorded The Visitation, a trippy if unremarkable self-funded record of 1969-ish garage rock. When singer-guitarist Helios Creed (born Barry Johnson) moved to San Francisco from Oahu and joined the band for their next album a year later, he was determined not just to create new sounds with his suitcase full of effects pedals but also to tap into the energy that was starting to reemerge in San Francisco’s post-hippie daze: “Punk came into view. We sorta’ wanted to be a punk band, but it was too late … there were already a bunch of punk bands in the city.”4 Half krautrock timbre twiddling and half psychedelic throwback, the band was too old and heady for the punk scene, not bluesy enough to mesh with post-hippie rock, and lacking the sense of terror that characterized the city’s industrial crowd, as we’ll see; Chrome’s uneasy fit within San Francisco’s music scene wasn’t helped by the fact that they almost never played live. Instead, Damon Edge, Helios Creed, and their bandmates spent time dropping acid (“LSD was very square”) and fiddling with recording technology—a decidedly unpunk thing to do at this early point.5

Specifically, they stumbled onto noise collage and effects processing, taking them to sonically disfiguring extremes. Creed recalls:

Damon played me these weird tapes he’d made, I go, “Man, I like that better than our [rock] set, why don’t we do something like that.” Then we talked about it for hours, all of a sudden we cut up our set with this weird shit next thing you know we made Alien Soundtracks.

This was the band’s second album.6 The record came packaged with photocollages of facially rearranged children and a portrait of Dwight Eisenhower. Its lyrics were laced with Fritz Lang–inspired science fiction, and its blend of tape drones and punk songs played through flangers sounded like little else at the time. “TV As Eyes” is a good all-in-one example of their sound: ninety seconds of an overmodulated backbeat and glammy singing followed by forty-five seconds of rhythmless cut-up television dialogue, distorted, flanged, and underlaid with a doomy electronic bassline.

The closest of any early quasi-industrial act to actual rock and roll, Chrome occupies an important space in the long history of the guitar within industrial music. While Throbbing Gristle carefully avoided the trappings of traditional chord-based musicality, Chrome was less compelled by the pan-revolutionary than by the promise of a good psychedelic freakout. More specifically, amid thin, uncompressed real drums and an occasional use of verse-chorus structures, one hears in Chrome’s music a washy phasing effect on Creed’s guitar. KMFDM’s En Esch warns that in industrial music, if you “were over the hippie thing, [you] didn’t use the phaser anymore,” and indeed these features in Chrome’s music have led critics and fans alike to suppose that the band was decidedly not “over the hippie thing,” imbuing them with a certain passé groovyness.7 Something of a missing link, Chrome helps to clarify an industrial musical heritage of circa-1970 space rock, including Hawkwind (cited by P-Orridge as an oft-overlooked influence), Brian Eno (idolized by Cabaret Voltaire), Arthur Brown (who later collaborated with Die Krupps), and the pantheon of German experimental outfits: Kraftwerk, Can, Neu!, Amon Düül, Faust, Cluster, Popol Vuh, and Tangerine Dream.

Chrome’s role in industrial music is transitional, though their professed inheritors include the likes of Skinny Puppy. The band occupies an optimistic convergence of San Francisco old and new, where the city’s other noisemakers, as we’ll see, take a more vexed position. Chrome embraced the past while tripping into the future, but in doing so they help us see, by contrast, the anti-hippie streak that pervades so much industrial music otherwise, one that reveals an Oedipal rage: a simultaneous rejection of and longing for the optimistic womb of 1960s idealism.

An historical and ideological tension specifically took hold in San Francisco because of the role of radical art and politics in shaping the city’s tolerance for the strange. An edgy streak thoroughly pervaded the local culture, even to the point where it may have risked undermining an actual sense of rebellion. Universities, corporations, nonprofits, and municipal government have long invested in San Francisco’s freethinking politics and the arts, greasing the wheels for many to live off their creativity. As far as industrial music is concerned, examples of this go back at least to 1947, when Kenneth Rexroth and Richard Moore, libertarian poets and activists, founded KPFA (with the help of pacifist Lewis Hill); it became the first expressly progressive radio station in the United States, later serving as a mouthpiece for the city’s forward-looking artistic, social, and political communities. A later instance is the Tape Music Center, established in 1961 when students Pauline Oliveros, Morton Subotnick, and Ramon Sender assembled a makeshift electronic studio in a San Francisco Conservatory attic. After functioning autonomously for several noisy years, the group received a $15,000 grant that led to their being wholly assimilated into Mills College’s Center for Contemporary Music. And it wasn’t just that offbeat ideas easily landed organizational funding; San Francisco citizens were often game for avant-garde happenings en masse. In 1969, artist Paul Crowley teamed up with composer Robert Moran and musician Margaret Fabrizio to conduct the free-for-all event “39 Minutes for 39 Autos,” a coordinated dance of timed headlights and car horns, the score of which had been printed in that morning’s San Francisco Chronicle. According to Baker’s Biographical Dictionary, a hundred thousand San Franciscans joined in.

The success of radical arts in the city meant that in the 1970s, some composers, poets, publishers, dancers, and sculptors who might have been enfants terribles a few years earlier or a hundred miles away were instead institutionally celebrated and publicly accepted as elders. Examples abound, such as the veneration of publishers like City Lights Books, the postmortem apotheosis of Jack Kerouac and Janis Joplin, and the hipster intelligentsia’s acceptance of Terry Riley, La Monte Young, and Steve Reich as new faces of twentieth-century composition. A cynical eye in the 1970s might already have begun to see the city’s role in trickling up the PBS-cool yuppie highbrow of the future.

Popular retrospectives of the late 1960s sometimes cast the hippie movement and its outgrowths as idealistic voices for positive change, waging peace against a backward culture and oppressive, warmaking governments. In the mid-1970s, though, the triumphs and failures of the hippies were unromantically fresh and bitter in the minds of their younger siblings, who now as twenty-year-olds were hanging out at Cafe Flore in the Castro and going to shows at the Art Institute. In the tired aftermath of the 1960s, this group redrew an alternative map of the decade into one that allowed a way forward, one whose lines of flight had not already been trampled by a failed movement. For these brooders, a secret history of the 1960s might focus on the exploitative Italian Mondo films that in the tradition of circus freakshows displayed animal cruelty and third-world mystic rituals, complete with naked tribespeople. Or the syndicated gothic soap operas Dark Shadows and Strange Paradise. Or right there on the streets of San Francisco, one could focus on Anton LaVey’s 1966 founding of the Church of Satan. Or the cult murders in the spring and summer of 1969 by sometime Bay Area resident Charles Manson and his followers. Or the local filmmaker Kenneth Anger, who in 1964 imbued his film Scorpio Rising with concentration camp imagery and a homoerotic Christ narrative, and whose 1969 Invocation of My Demon Brother portrayed an obscure occultic ritual that prefigured the giallo horror of Dario Argento.

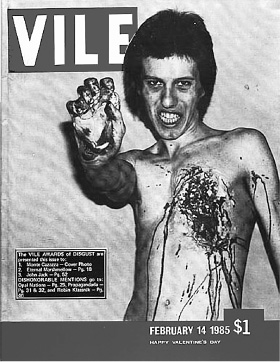

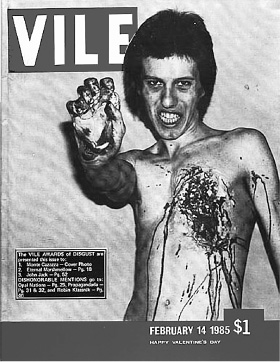

This had been the 1960s for Monte Cazazza, who was among the first would-be industrialists to start making noise. Cazazza’s early art and collaboration cast him as an astute torchbearer of Dada, participating in Ray Johnson’s 1970 New York Correspondence School exhibit and joining the Bay Area Dadaists. But toward the mid-1970s, he began showing off a pre-punk verve: his 1973 zine Nitrous Oxide contained spray-painted pages and a savagely tasteless romance column, and his visual art also appeared in issue two of The West Bay Dadaist, a thin 1973 volume emblazoned with the slogan “Do It Yourself!” (In this homemade publication, incidentally, art by Genesis P-Orridge appeared alongside Cazazza’s; they would meet in 1976 and collaborate for years after.) In 1974, he modeled on the cover of Vile, a zine drafted to mock the Canadian anti-mail art publication File (itself a parody of Life). Growing tired of mail art’s tame fun, in the picture, Cazazza appears to have ripped his heart out of his own chest. He sneers salaciously as he holds the organ up to the camera.

Figure 6.1: Cazazza on the cover of Vile exemplifies an emerging strain of misanthropy in mail art. Photograph by Monte Cazazza.

Cazazza sought to portray himself as uncouth, craven, and genuinely dangerous. Ultimately these leanings developed into a compendium of anecdotes about his artmaking. For his first sculpture assignment at the Oakland College of Arts and Crafts, he supposedly poured a “waterfall” of cement over the school’s main entrance—a prank for which, rumor has it, he was expelled. Slash vol. 2 no. 3 regales that at an arts retreat Cazazza “arrived with an armed bodyguard and sprinkled arsenic into all the food. At lunch he dropped bricks with the word ‘dada’ painted on them on artistic feet. At dinner he burned a partially decomposed, maggot-infested cat at the table.”8

Given Cazazza’s proclaimed affinity for James Patrick Chaplin’s book Rumour, Fear, and the Madness of Crowds9 and his own musings on the importance of “Misdirection: making something that isn’t seem to be what it is,”10 one might see through this lens that perhaps Cazazza’s physical and sonic artifacts are less the site of his artistic achievement than their memory and the reputation to which they contribute. Cazazza’s art blends cultural realities with his own disinformation. He did this initially through photocopied collage, later through sampling (his excellent 1982 song “Sex Is No Emergency” lifts its rhythm track entirely from Trio’s hit of the same year “Da Da Da”), and eventually in his 1987 mondo-esque shockumentary True Gore, where fake interviews with serial killers and bloody special effects flank real news footage. In 1977, he staged photographs with the members of Throbbing Gristle to resemble the execution of murderer Gary Gilmore, one of which was convincing enough when mailed as a postcard that it allegedly made the cover of the Hong Kong Daily News. His compilation album The Worst of Monte Cazazza begins with a fictional “Dr Alberti” delivering his “Psychiatric Review” of Cazazza: “We’re dealing with a primitive filthy-minded vulgar embarrassing twisted mind. … Basically, this is a worthless racket. The man is mentally incompetent.”

Cazazza, by integrating fact with his own invention so consistently, balances on the border of urban legend believability, retaining his image as a rabid manchild art terrorist (whether or not, in his erudition, he actually lives up to it). As a connecting personality between the U.S. and UK industrial scenes, he’s repeatedly cited by industrial archivists V. Vale, Karen Collins, and Brian Duguid as a leader in the genre’s history, but his musical output is nearly nonexistent: as a solo artist in the 1970s and 1980s, he released two singles, a four-song EP, and a small handful of compilation tracks—barely a half-hour of music, all told. Cazazza’s work is marked by scarcity. His personal narrative is similarly marked by outlandish irreproducibility—for example, when asked about allegedly killing an assailant in self-defense, he replies, “Of course I can’t confirm a story like that.”11 This combination of attributes calls to mind the early media theorist Walter Benjamin, who asserted that not only are original, nonreproduced artworks ritual in their nature (as is literally the case with so much of Cazazza’s performance art) but “what matter[s] is their existence, not their being on view.”12 Taken into account with the democratizing reproducibility of mail art and zines—media in which Cazazza was also active—his oeuvre makes for a multilayered study in access to information. It wasn’t until Cazazza’s reputation was more fixed that any amount of his recordings (the aforementioned Worst of compilation from 1991) became readily available at all—and this might have more to do with public interest in industrial music than in Cazazza at that moment. It’s true that he coined the Industrial Records slogan “Industrial Music for Industrial People” and might by extension be responsible for the whole genre’s name, but when we consider Monte Cazazza and his role both in the San Francisco scene and in industrial music, his contributions are only limitedly as a sonic pioneer; arguably his best music was produced in collaborations. But to be sure, Cazazza is a propagandist—living evidence that reality is nothing more than the perception of reality. The notion of memory on which his significance relies both further connects San Francisco’s scene to a dialogue with the past and renders his past provocations ongoing still.

Z’EV (born Stefan Joel Weisser) was another important character in San Francisco’s late 1970s industrial scene. Already a veteran of the rock circuit and an armchair ethnomusicologist, after moving to the city in 1975 he quickly fell in with well-read misfits, playing in bands at art spaces and at Mills College. He eventually achieved greater notoriety by touring the East Coast of the United States and heading to Europe. His politics were radically anticorporate, anti-government, and ecologically prescient. Using recycled, reappropriated, and stolen materials (“thievery … has to do with the very big premium I put on risk in the production of works”), Z’EV would pound on, drag, and crush his homemade instruments.13 Trained initially as a drummer, he, like many other well-educated industrialists, attempted to bypass his schooling in favor of something more immediate. Where Cazazza turned toward the bestial, Z’EV sought out the mystical, conceiving of his performances as rituals. An enthusiast of voodoo, Kabbalah, and the writings of Edwardian occultist Aleister Crowley, Z’EV lists among his axioms “DEVOTION THROUGH SACRIFICE the DISCIPLINE (purifying and consecrating the vessel) to translate/transpose this into a/the performance context; DOING not THINKING: invoking/evoking, by analogy, a ‘model’ on the physical plane of the archetypical process, channeling ‘thought-form/energy/action(s)’ into manifestation.”14 The quasi-Burroughsian desire to “exterminate all rational thought” is a consistent thread in industrial music: Boyd Rice of NON, who would later collaborate with many in the San Francisco set, explains, “My ideology then was about the instinct. It was about not thinking. My intention in doing music was just to drive the thought out of people’s heads.”15 The irony in these musicians’ privileging the physical and the psychic over the intellectual is that, as mentioned, they nearly all chose this primitivist path as a reasoned, intellectual response. Industrialists’ modernist desire for something genuinely new speaks to the very headiness from which they tried to escape. Rice continues:

I was interested in music, and there were always people in the press who would say, “This is the next big thing. Oh my God, this is going to change everything,” and then I’d get the record and it would be the same old stuff that everybody has been doing for years. I mean, Patti Smith—“Oh she’s a poet, it’s completely different!” and you’d get this album and you’d think, “Big fucking deal. …” I want to have music that’s completely different.16

Another artistic and spiritual axiom that Z’EV lists is that “PROCESS is THE Vehicle for the source and protection of experimental information/influx—situations/manifestations as performance (and yes, even entertainment).”17 As discussed in this book’s early chapters, the process and ideology behind early industrial is often a stronger defining feature than the notes, rhythms, and timbres of the music. Indeed, some of Z’EV’s early recordings exhibit a clear organizational process, such as the use of phasing on his 1977 speech-based “Book Of Love Being Written As They Touched …” while other works of his become undifferentiable washes of plastic and bells, clattering through echo devices until, by processing, rhythm melts into timbre. Witnessed live, this music is immensely physical—something lost on record.

In the same vein, Mark Pauline and his Survival Research Laboratories are an industrial spectacle without peer, but as with both Z’EV and Cazazza, their significance lies beyond the scope of vinyl and tape. Founded in 1978, initially they in fact made no “music” at all. (Matt Heckert introduced a “soundtrack” component to the group in 1981, but departed in the summer of 1988). Pauline, a college-educated recreational vandal and political prankster, teamed up with Heckert and Eric Werner to build large machines that wreaked destruction on one another and their surroundings. Survival Research Laboratories’ performances—the first was called “Machine Sex” in early 1979—took up huge spaces and occurred at gas stations, in vacant lots, and beneath bridges. In them, these colossal robots would shatter glass with air pressure, hurl explosives, blow flame, and circle one another with swinging blades. It was an expensive endeavor, but partially enabled by Pauline’s free access to a junkyard and his brazen enjoyment of outright theft. Shows were organized around political or mechanical themes—“an exploration of the mechanics underlying reactionary thought”—or the animation of dead animals with robotics. With loud soundtracks often provided by the other San Francisco artists discussed here, the shows reveled in an antisocial violence that didn’t just reimagine the San Francisco of the 1960s but detested it—“I hated hippies. Hippies were for peace,” Pauline says.18 On many occasions, spectators have been injured. During a 1982 concert, SPK’s Graeme Revell set an audience member on fire with Mark Pauline’s flame thrower, and in a 2007 performance in Amsterdam, Survival Research Laboratories crew member Todd Blair was struck in the head by a machine, disabling him permanently.

Survival Research Laboratories offered a cathartic experience in which technology served no purpose other than to destroy itself exhibitionistically. Where Einstürzende Neubauten and the Berlin scene centralize and exhaust the body in breaking free from (and with) technology, humans are absent from Mark Pauline’s stage (“If you start having human performers, you’re very limited”).19 Here there’s no need to tear buildings down: they will do it themselves. This may reflect a key difference between Berlin’s history of suffering and San Francisco’s sunny art-as-life-as-art. Pauline’s blowing apart his right hand with a rocket motor in 1982 probably also reinforced his desire to keep some distance between machines and makers.

The size and spectacle of Survival Research Laboratories’ performances made them an exciting and unique part of the San Francisco scene, and they were very much in dialogue with other early industrial musicians. In their social and totemic role, they acted as essential nodes at a time and in a place vital to industrial music’s momentum as an art, but Survival Research Laboratories greased the gears rather than made the noises: they had no product to distribute, their machines were dismantled after (or destroyed by) shows, and their performances were infrequent and usually unrecorded. The group is thus legend within industrial communities in the truly folkloric sense that a trail of recordings might even disrupt. In fact, given the broad scarcity of available artifacts from the San Francisco industrial scene in the late 1970s and early 1980s, we might see a resonance in Z’EV’s observation: “It is most telling that the songs sung by the Nine Muses are designated as mnemosyne: the memory of what is, what was, and what will be. True music? No one writes it or plays it so much as you remember—to—hear it.”20

That view is an historical one, however. In the actual moment of late 1970s San Francisco, the value of art and music was staked on its living politics and not on some envisioned future legacy. The city particularly privileged music’s social dimensions over its formal ones; just think of the cult that surrounded the ever-changing performances of hometown heroes the Grateful Dead.

Integral to these social interactions within the Bay Area soundscape was San Francisco’s visible gay community, which fostered a racially diverse cast of artists, promoters, and patrons. The synergy they cultivated was evident even in traditionally straight and white subcultures, as Factrix’s Bond Bergland remembers: “The gay scene and the punk scene were very fused. The gay thing was instrumental in forming the punk aesthetic and everything about it. It was the most advanced scene artistically. It was the only game in town.”21

Culturally savvy, San Francisco was therefore immediately plugged into punk once it began in 1976. By 1978, live punk shows were the religion of San Francisco’s underground music scene, and the Mabuhay Gardens in North Beach was its church. With concerts serving as a flexible, affordable, and interactive means of musical socializing, San Francisco bands of the day were less likely to put out independent vinyl releases than acts in London or New York, but the nightlife was just as vibrant. “All the people in The Industrial Culture Handbook started out with punk rock,” says the volume’s editor V. Vale.22 In particular Mark Pauline recalls, “I appreciated a lot of [punk’s] ideas and the fact that it was geared … toward getting out information that had previously been relegated to the underground art scene of the sixties and seventies.”23

“Getting out information” served as an important common ground between punk and industrial movements both in exposing the evils of control authorities and in offering alternative worldviews, histories, and entertainment to a hungry counterculture. Monte Cazazza, for example, prided himself on publicly playing obscure rare audio recordings of cult leader Jim Jones, or screening stolen medical testing videos during live performances. Whatever the venue and whatever the crowd, San Francisco’s musicians seem to have focused more on the act of disseminating subversive ideas than on the particulars or the fixity of the material itself. The most opulently bizarre underground performers in town were the Residents, whose elaborate stage productions featured the band’s members wearing tuxedos and, beginning in 1979, giant eyeballs as full headmasks.

Performance extended beyond the concert venue too. No study of information access in the San Francisco scene would be complete without acknowledging the project that Mark Hosler and his friends dubbed Negativland. In 1979, when Hosler was still in high school, he began experimenting with tape collage, inspired significantly by the Residents’ work on their 1976 The Third Reich ‘n Roll, in which they overlaid and manipulated vintage pop to create montage monstrosities. Starting in 1981, Negativland melded recording and live performance by hosting a weekly radio show every Thursday at midnight on the aforementioned KPFA. On this show, called Over the Edge, the group would improvise live cut-ups, mashups, and collage in the name of “culture jamming” (Hosler’s own term, which has since taken on a life of its own). The focus on improvisation and music making in real time ostensibly safeguards against one’s art becoming reproducible and commodified, though Negativland did make records too. Like the Residents, Negativland wasn’t ever fully part of any industrial scene (despite their 1987 club hit “Christianity is Stupid”), but their oddball contributions to the experimental soundscape of the Bay Area and to sampling as a political practice both warrant their mention here.

In his introduction to RE/Search Publications’ 1983 Industrial Culture Handbook, the famous punk journalist Jon Savage identifies five ideas central to industrial music practice:

1. Organizational autonomy

2. Access to information

3. The use of synthesizers and antimusic

4. Extramusical elements

5. Shock tactics24

This little list has taken on a life of its own in scholarship about industrial music, and even though this book doesn’t especially take the list’s items as gospel—for they are collapsible, of incomparable orders, and incomplete—Savage’s tenets still make for a good checklist of the Bay Area industrial music practices in the late 1970s and early 1980s. To many, in fact, Savage’s two-page introduction in which he lays out these tenets is the most memorable part of the Industrial Culture Handbook.

A heady band like Factrix has a lot to say about organizational autonomy and shock tactics. They describe themselves, for example, as “the sound of a bad trip. Like you suddenly wake up with no memory of what happened, but the knife is still in your hand.”25 Factrix established an aesthetic template that many acts in the genre would adhere to in the coming years.

Although Z’EV’s music was almost solely percussion, Factrix (like local synthpop stars Tuxedomoon) used no drums, instead employing a low-tech drum machine and tapes. When they really needed to bang on something, a battery of metal, plastic, and glass did the job. Factrix could write actual songs—the two-chord “Ballad of the Grim Rider” has a postpunk Ennio Morricone flavor—but obscuring this on most of their studio and live recordings is a never-ending wash of noise, either from member Joseph Jacobs’s tape recorder or from modified guitars, processed Throbbing Gristle–style until they groaned dully. At live shows, singers Bond Bergland and Cole Palme would hunch over their instruments, their high mumbles cutting through the shifting reverb that the band applied to every sound. Their music was undanceable, creaking, and often asphyxiatingly dense, but it managed at times to find a proto-goth vibe that verged on enjoyable; check out their Scheintot album’s sendoff track “Phantom Pain,” recorded in 1980.

Like the English industrial bands of the era, Factrix had an interest in new sound textures afforded by technology: their tools guided their music in a way that separates them from Z’EV and Cazazza, whose personalities and artistic intent relegated musical materials to secondary importance. Perhaps more than any other industrial act of the 1970s, Factrix were aesthetically honed in on the emotively eerie. Dressed in black with black-dyed hair, the band proclaimed allegiance to ex-surrealist Antonin Artaud and his Theatre of Cruelty. Factrix were, according to postpunk chronicler Simon Reynolds, not so much “art damaged as Artaud-damaged.”26

All cleverness aside, the band’s specific adherence to the Theatre of Cruelty ought not be taken as simply yet another shade of modernism in the industrial patina. As will be discussed in Chapter 11, Artaud’s ideas about performance are insightful lenses for looking at industrial music. But for the purposes of understanding what industrial music gained from Factrix’s San Francisco–based work, it’s enough at the moment to say that their interest in Artaud compelled them to shock audiences with the grotesque, the dreamlike incomprehensible, and the excruciating interruption of drumless, womblike textures with jarring taped noise. Reciprocally, San Francisco was uniquely equipped to introduce Artaud as a precondition to Factrix: local beatnik Lawrence Ferlinghetti compiled, translated, and published (through City Lights Books) the 1965 Artaud Anthology, and the nonprofit arts complex Project Artaud has operated in the Mission District since 1971. Factrix performed there in March 1980 with Mark Pauline, Z’EV, and NON.

Factrix is lesser known today than Cazazza, Survival Research Laboratories, and Z’EV, but this isn’t because they were lesser artists; nor is it for a comparative lack of recordings. Instead, it comes back again to the issue of memory—specifically the fact that the aforementioned Industrial Culture Handbook of 1983 devoted articles to the likes of Cazazza and Z’EV (“I did him a huge favor by putting him in there,” says editor V. Vale) but not to Factrix.27 In the late 1970s, Vale (born Vale Hamanaka) had been in charge of San Francisco’s influential punk zine Search and Destroy, which he’d begun as an employee at City Lights. When he and Andrea Juno published The Industrial Culture Handbook in 1983, they were compiling and bibliographing what they considered a collective cultural statement whose incendiary articulation was short-lived. In fact, the book’s introduction declared industrial “over,” though Vale says, “I think Jon Savage was saying that as a provocation.”28 At any rate, Vale and Juno hadn’t anticipated the book’s steady popularity over thirty years, which not only helped to rebirth and perpetuate an increasingly global scene that some had left for dead but also inadvertently served to calcify it somewhat—note the instructional overtones of the word “handbook.” In this regard the memory of the recent past feeds into the reality of the future. The Industrial Culture Handbook has gone through seven printings, selling between twenty thousand and thirty thousand copies by Vale’s 2012 estimate; its inclusions and omissions have become as much a part of industrial music as any record’s noise.29

The San Francisco industrial scene changed but never fully wound down. Factrix disbanded after their live 1982 Cazazza collaboration record California Babylon, and Z’EV moved out of town. Early in the 1980s, Boyd Rice of NON connected with the city’s scene (more about him later), and extremist bands such as the German Shepherds were playing raucous shows. In the mid-1980s, the poppy Until December came out of the city’s leather culture (despite singer Adam Sherburne’s heterosexuality), and into the next decade the label COP International and acts such as Grotus and Gridlock would emerge.

From San Francisco’s original cast, industrial music gained a highly literate if self-rejecting sense of intellectual heritage, a knack for shock (both as Artaudian tactics and self-promoting villainy), and a sonic fondness for guitar-rich swirls that hint almost optimistically at a science fiction horizon beyond the postindustrial. An urban microcosm of twentieth-century revolutionary politics, San Francisco gives a steeply pitched landscape to industrial music’s role in the history of artistic radicalism.

ICONIC:

Monte Cazazza – “To Mom on Mother’s Day” (1979)

Chrome – “The Monitors” (1977)

Factrix – “Anemone Housing” (1980)

The Residents – “Constantinople” (1978)

Tuxedomoon – “No Tears” (1978)

ARCANE:

The German Shepherds – “I Adore You” (1981)

Minimal Man – “Loneliness” (1981)

Negativland – “#12” (1980)

Boyd Rice – The Black Album (1975)

Uns – “Aldo’s Bar” (1980)