Chapter 6

One Foot in the Tomb: Ancient Egyptian Art

In This Chapter

Reading one of the oldest historical documents in the world

Reading one of the oldest historical documents in the world

Sizing up the pyramids

Sizing up the pyramids

Exploring the art of Egyptian tombs

Exploring the art of Egyptian tombs

Reading a Book of the Dead

Reading a Book of the Dead

Understanding why Egyptian statues are so colossal

Understanding why Egyptian statues are so colossal

The mountain-high pyramids and stony stare of the Great Sphinx have awed mankind for thousands of years. The ancient Greek historian Herodotus wrote, “There is no country that possesses so many wonders, nor any that has such a number of works which defy description.” The Roman leaders Julius Caesar and Marc Antony were so impressed by Egyptian culture and wealth that they had to first marry Egypt (in the form of Cleopatra) and then rule it. The mystique of Ancient Egypt still captivates modern man. But today Egypt’s biggest draw isn’t the pyramids or Cleopatra, but Egyptian mummies, magic, and tomb art.

Mummies and the magical resurrection rituals painted on the walls of tombs and coffins have inspired witches’ spells, short stories, movies, documentaries, art historians, archeologists, and even the fashion industry. The film companies of the world have unreeled more than 90 mummy movies since the dawn of cinema, from a French short in 1899 about Cleopatra’s mummy to Hollywood’s The Mummy in 1999 and the made-for-TV The Curse of King Tut’s Tomb in 2006. The Three Stooges even got into the act with We Want Our Mummy (featuring King Rootin-Tootin) in 1939 and their more mature work, Mummy’s Dummies, in 1965.

Mummies, medicine, and magic

Mummies have teased people’s imaginations since at least the Middle Ages when people believed they had healing powers. Twelfth- century doctors prescribed mummy dust (made from pulverized corpses) for wounds and bruises, and until around 1500 people ingested mummy powder to relieve upset stomachs. Even in the 17th century, witches — like those depicted in Shakespeare’s Macbeth — used mummies to help them forecast the future.

Ancient Egypt 101

The discovery of King Tut’s tomb in 1922 made front-page news and spawned an Egyptian fashion craze. Women forgot their distaste for bugs and put on scarab-beetle jewelry, donned pharaoh blouses with hieroglyphic prints, and carried golden pyramid- and sphinx-shaped ladies’ compacts.

Napoleon triggered the global fascination with Egypt in 1798 when he led the first major scientific expedition there, while trying to conquer Egypt and Syria. Egyptology (the study of Ancient Egypt) has been almost a cult science ever since.

| Period | Dynasty | Date |

|---|---|---|

| Predynastic | 0 | 4,500 B.C.–3,100 B.C. |

| Early Dynastic | 1st–3rd | 3,100 B.C.–2613 B.C. |

| Old Kingdom | 4th–6th | 2,613 B.C.–2,181 B.C. |

| First Intermediate | 7th–10th | 2,181 B.C.–2,040 B.C. |

| Middle Kingdom | 11th–14th | 2,133 B.C.–1,603 B.C. |

| Second Intermediate | 15th–17th | 1,720 B.C.–1,567 B.C. |

| New Kingdom | 18th–20th | 1,567 B.C.–1,085 B.C. |

The Nile River was the lifeline of Ancient Egypt. Without it, the most durable civilization in history couldn’t have survived. Herodotus said Egypt is “the gift of the river.” He was right. The Nile’s annual summer floods fertilize the land around it, which otherwise would be desert. Most Egyptian cities and tombs hug the banks of the Nile like children clinging to their mother. If you venture too far from the river, you end up in the desert like Moses did.

The ancient Egyptians believed the Nile’s life-giving floods, which occur during the hottest and driest part of summer, were the gods’ gift because they didn’t appear to be caused by the weather. The rain that swells the Nile actually falls hundreds of miles away in Ethiopia in the tributary called the Blue Nile — but before the advent of the Weather Channel, the floods in Egypt appeared to arrive miraculously.

The Palette of Narmer and the Unification of Egypt

During the Predynastic period, the tribes of Lower and Upper Egypt gradually formed into two separate nations, which were united at the dawn of history in about 3100 B.C., possibly by Narmer, the first pharaoh of the first dynasty.

Mummification

Because Egyptians believed the ka (soul) reunited with the body in the tomb, the body had to be painstakingly preserved through mummification. Mummification consists of three basic steps:

1. Remove the body’s organs, preserving the important ones in jars.

2. Dry the corpse (because moisture causes decay).

3. Wrap the body with layers of linen bandages.

Embalming priests extracted the organs through a slit in the stomach, dried the body for 70 days with natron (baking soda and salt), and then bandaged it up.

Incense, jewels, and herbs were often laid between the layers of bandages or mummy clothes.

The Palette of Narmer is a two-sided work of art. On one side, Narmer wears the white, bowling-pin crown of Upper Egypt (see Figure 6-1); on the other side, he wears the red, hatchet-shaped crown of Lower Egypt (see Figure 6-2). The artist made Narmer at least two times bigger than the people around him to show his superiority and divine status. Pharaohs were considered gods in Ancient Egypt. (A pyramid text says, “Pharaoh’s lifetime is eternity / His limit is everlastingness.”)

|

Figure 6-1: The Palette of Narmer chronicles a victory of King Narmer over his enemies. Here, the pharaoh clobbers a kneeling enemy. |

|

Werner Forman / Art Resource, NY

|

Figure 6-2: Check out the pharaoh looking at his decapitated enemies who have been stacked with their lopped heads between their legs (in the upper-right-hand corner). |

|

Werner Forman / Art Resource, NY

Discovered in Hierakonpolis, the ancient capital of Upper Egypt, the Palette of Narmer is perhaps the world’s oldest historical document, dating from around 3100 B.C. It resembles the small palettes on which Egyptians ground the pigments for their eye makeup, but seems far too big to have actually been used for that purpose. The reliefs on both sides of the green siltstone (25 inches high) tell the story of the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt in horizontal bands, kind of like a comic strip. There’s even some helpful text (comic-book text bubbles) in hieroglyphics, the picture language of Ancient Egypt. We can’t read every part of the palette, but we can interpret a lot of it.

The hieroglyph for Narmer’s name — a catfish perched on a chisel — appears at the top on both sides. Clearly Narmer, the big guy on the palette, is the main character in the story. Notice that a pair of cow heads in the top strip set off Narmer’s hieroglyph — like bookends. Hathor, the motherly cow goddess, is often viewed as the mother of pharaohs. Placing Narmer’s name between images of Hathor suggests his divine origin.

On one side (see Figure 6-1), the pharaoh clobbers a kneeling enemy. The victim resembles the two sprawling, naked guys in the bottom band. Appar- ently, they’ve already been clobbered and are now worm’s meat.

When Moses meets god in the Old Testament, the first thing God tells him to do is take off his shoes. (Exodus 3:5 says, “Put off thy shoes from off they feet, for the place whereon thou standest is holy ground.”) Here, Narmer is also shoeless. A servant behind Narmer carries the pharaoh’s sandals. Is there a connection? Why does Narmer have to remove his shoes to clobber somebody? Perhaps because slaughtering defeated enemies was viewed as a religious ritual because the divine pharaoh was always right. (People always find ways to justify their brutalities.) Also, like Moses, Pharaoh is in the company of a god — in this case, Horus, the hawk-god hovering over him.

Horus, the god of war and light, is sometimes depicted as a man with a hawk’s head and other times simply as a hawk. Here he is represented as a hawk with one claw and one human arm with which he de-brains an enemy who is attached to a bouquet of papyrus plants. (In the process of mummification, the embalmer drained the dead person’s brain through the nose, which is what Horus seems to be doing to the head.) The fact that the hawk stands atop papyrus plants, the symbol of Lower Egypt, shows that Lower Egypt has been subdued. Also, Horus’s action parallels the pharaoh’s and indicates that Narmer’s deeds are in harmony with the gods’.

On the flipside of the Palette of Narmer (refer to Figure 6-2), Narmer, identified by his size and by the hieroglyphic nametag next to his head, is shoeless again. So he’s probably performing another religious act, inspecting decapitated enemies who have been stacked with their lopped heads between their legs. A priest and pharaoh’s standard bearers march before him. Their respective heights suggest their rank.

On the next lower strip, two snake-necked lionesses face off. Their entwined necks and perfect symmetry may suggest the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt, and that both halves of Egypt are equal. Note that two of the pharaoh’s men restrain the lionesses, implying that the two Egypts need to be governed by a strong hand, Narmer’s.

In the bottom band, a bull (possibly the Apis Bull, which was a god) tromps Egypt’s enemies, while knocking down a fortress with his tusks. Bulls were often used to depict the might of pharaoh.

Both sides of the palette paint a picture of Egypt’s strength and unity under the divine rule of Narmer.

The Egyptian Style

Though it’s a very early work, the Palette of Narmer (see the preceding section) is representative of all later Egyptian art. The Egyptian style, once estab- lished, hardly ever changed. Notice that part of the pharaoh is shown in profile, while the rest of him is represented in frontal view. In 3,000 years of Egyptian art, the pharaoh never changes his pose (in side-view reliefs and paintings). The pharaoh’s legs are always shown in profile, with the flat left foot planted in front of the right. The chest and shoulders are in frontal view, while the face is in profile (except for the right eye, which you see head-on, so to speak).

Artists used the same canon of proportions to sculpt statues, but the figure was depicted frontally rather than in partial profile. Also, the left leg of the statue steps forward, more so in men than women (the more testosterone, the bigger the step), as in the statues of King Menkaura and his queen from the 4th dynasty. Despite their stoic faces, notice the intimacy and sculptural harmony of the pair. They look like they were made for each other. King Menkaura and his queen, who seem as durable as the pyramids, represent the stability of the Old Kingdom.

Excavating Old Kingdom Architecture

Old Kingdom pharaohs ruled Egypt liked gods on earth. Their power and financial resources must have seemed limitless and are best represented by the Great Pyramids and mighty Sphinx of Giza, who has the body of a lion and the head of Khafre, the fourth pharaoh of the 4th dynasty. Even after four and a half millennia of dust storms, the majestic 65-foot-high sphinx still stares boldly at the world (though its eyes are eroded).

The pyramids grew in steps, literally. They began with small mastabas, which seemed to grow with the prestige of the pharaohs during the 1st and 2nd dynasties. A mastaba is a mud-brick rectangular slab with doors and windows. It included a mourning room for visiting relatives and a sealed chamber for the deceased person’s soul. The mastaba was attached to an underground tomb by a long shaft cut into rock.

During the 3rd dynasty, stone stairways to heaven called step pyramids were erected over the mastabas to ensure their permanence and give kingly tombs a grander appearance. The greatest is the Step Pyramid of King Djoser (2667 B.C.–2648 B.C.), the second king of the 3rd dynasty.

Until about 2690 B.C., Egyptians used primarily mud brick, wood, and reeds to build mastabas and temples. The first totally stone structure was King Djoser’s Step Pyramid, which was raised in the necropolis (city of the dead) at Saqqara, just south of modern-day Cairo.

Erecting the first all-stone structure took an innovative mind, someone with the vision to break with tradition and think outside the box — or, in this case, mud-brick mastaba. Imhotep, whose name appears at the base of a tomb statue of Djoser in the Step Pyramid, was just that. He is the first known artist and architect in history and was referred to as the “Chancellor of the King of Lower Egypt, the first after the King of Upper Egypt, Administrator of the Great Palace, Hereditary Lord, the High Priest of Heliopolis, Imhotep, the builder, the sculptor, woodcarver” (try fitting that on a nametag). He was also a famous physician and magician. (Medicine and magic were the same thing in those days.) In late Egypt, Imhotep was viewed as the god of medicine and healing and had shrines in parts of Egypt and Nubia. (Boris Karloff plays Imhotep in the 1932 film The Mummy. Arnold Vosloo plays him in the 1999 The Mummy and the 2001 film The Mummy Returns.)

Imhotep’s Step Pyramid is similar to a Mesopotamian ziggurat (see Chapter 5). It seems to be a spiritual launch pad, designed to give the pharaoh’s soul a boost into heaven, one step at a time.

In the 4th dynasty, the Step Pyramid evolved into the familiar four-sided pyramid like the Great Pyramids at Giza.

The oldest and biggest of the Great Pyramids, completed in about 2560 B.C., was erected by Khufu (a.k.a. Cheops) who ruled Egypt between about 2589 B.C. and 2566 B.C. Khufu’s pyramid took roughly 20 years to build, stands 450 feet high, and is built on a 13-acre square base! Originally the pyramid stood at 481 feet, but its polished limestone veneer, which added about 30 feet to its height, has deteriorated. The sides of the pyramid are equilateral triangles that face due north, south, east, and west. They are aligned perfectly to one tenth of a degree to the cardinal points on a compass.

The pyramid is part of a vast funerary complex that includes two mortuary temples, three smaller pyramids for Khufu’s wives, another small pyramid for Khufu’s mother, a causeway, and mastabas for nobles linked to the pharaoh.

The pyramid shape duplicates the sun’s rays streaming through an opening in a cloud. Because Egyptians believed that a deceased pharaoh rode to heaven on the sun god’s rays, the perfect pyramid may have been designed to facilitate his skyward ascent in a more refined fashion than the Step Pyramid.

The Rosetta Stone

In 1799, one of Napoleon’s officers, Captain Pierre-François Bouchard, discovered the Rosetta Stone, which was dated 196 B.C., in the port city of Rosetta (present-day Rashid). An important decree was inscribed on the stone in two languages — Egyptian and Greek — so everybody would understand it, like Canadian road signs that are written in both French and English.

One of the languages, Egyptian, was expressed in two different scripts. One of the scripts, hieroglyphics, was the sacred writing that Egyptian priests used. The other, demotic, was the common people’s script starting in the 8th century B.C. Greek was the language of the foreigners who ran the country.

The key was to find common ground between the three scripts. About 20 years after the Rosetta Stone was discovered, Thomas Young, an Englishman whose hobby was studying Ancient Egypt, matched a couple names in hieroglyphs on the top third of the Rosetta Stone with the Greek equivalents in the bottom register. In 1822, Jean-François Champollion, a French Egyptologist and the founder of scientific Egyptology, continued Young’s work, matching the hieroglyphic symbols of the names with phonetic sounds in a related ancient language that Champollion spoke, called Coptic. (Coptic is sort of an in-between language, halfway between Greek and Egyptian.) Soon Champollion figured out the whole alphabet. And the rest is art history.

The second largest pyramid is Khafre’s at 446 feet. The base covers 11 acres. It is accompanied by the Great Sphinx and a temple complex similar to Khufu’s.

Menkaure’s pyramid, the third of the three Great Pyramids, is much smaller than the other two, standing at about 203 feet.

Although pharaohs continued building pyramids until the New Kingdom, the great age of pyramid building ended with the Old Kingdom. Middle Kingdom pyramids are much less grand.

The pharaoh spent much of his life preparing for death. A new pharaoh built his own tomb — which was considered his second or eternal home — as soon as possible. (Who knew when he’d have to move in?) He stocked the tomb with provisions that he would need in the hereafter, including clothes, toiletries, jewelry, beds, stools, fans, weapons, and even chariots. King Tut was entombed with four golden chariots! After his death, the immense task of managing a pharaoh’s tomb was given to an entire town.

During the Middle and New Kingdoms, rich and middle-class Egyptians also built elaborate tombs. After their death, a family member known as “the priest of the double” managed the tomb and fed the dead relation from a sort of mummy menu, which included bread, fruit, meat, wine, and beer. For insurance, pictures of food were painted on the walls in case a descendant stopped supplying meals. The pictures, combined with the right spells uttered by the deceased’s spirit, would magically zap the food onto the table.

The tomb housed not only the mummy, but also the deceased’s ka, or soul, which was represented by a statue housed in a sealed-off part of the mastaba. The ka statue was a backup in case the mummy disintegrated or was stolen. The statue had to look like the dead person in order for its magic to work. The words carved from life are inscribed on many ka statues.

The Egyptians also preserved and mummified internal organs that the dead would need in the hereafter like the stomach for digesting delicacies on the mummy menu. The organs were stored in four canopic jars, which were usually capped by the animal heads of the four sons of Horus.

|

Figure 6-3: Ka statues, like those of Prince Rahotep and his wife, had to be realistic to perform their magic. |

|

Werner Forman / Art Resource, NY

The In-Between Period and Middle Kingdom Realism

In 2258 B.C., Egypt fractured into constellations of competing states. During this period, Egyptian people modified their view of the afterlife. Now petty princes and the rich who supported them could also have tombs to guarantee them a place among the stars. Instead of building pyramids (which would have been too showy), wealthy Egyptians carved their tombs in rock cliffs. Soon the pharaohs began to imitate them.

Trade expanded during the Middle Kingdom, especially during the 12th dynasty, creating a middle class who demanded rights, including admission to the afterlife. The demand for tomb and coffin paintings rose dramatically.

With these liberal trends, the rules for artists were relaxed somewhat. More naturalism was permitted.

The bust of Senusret III, a 12th-dynasty pharaoh, shows that the new realism applied to all ranks. His slightly downcast, heavy eyes and sensitive mouth show that he feels the burden of his rule. Senusret is represented more as a man than a god.

New Kingdom Art

The Middle Kingdom ended when the Hyksos, an Asian people, conquered most of Lower Egypt in 1720 B.C. The arts declined during this intermediate period, even though the Hyksos tended to respect Egyptian traditions. The decline ended in 1567 when Ahmose I, the founder of the 18th dynasty, reunited Egypt, ushering in the New Kingdom. Egypt expanded into Nubia and Libya during this period, becoming an empire. This expansion spread the influence of Egyptian art far beyond its borders and also brought foreign influences into Egypt.

Pharaohs stopped building pyramids and began to be buried in the Valley of the Kings in rock-hewn tombs on the West Bank of the Nile near Thebes (modern-day Luxor). The trend toward naturalism continued in the New Kingdom, especially during the reigns of Hatshepsut and Ahkenaten.

The 18th-dynasty female pharaoh Hatshepsut ruled from 1473 B.C. to 1458 B.C. She was the queen of her half-brother Thutmose II before becoming regent for her stepson Thutmose III and finally pharaoh after her husband’s death. During her 21-year reign, Hatshepsut cultivated peace instead of war, commissioned great building projects, and restored monuments destroyed by the Hyksos. She completed the tombs of her father (Thutmose I) and husband (Thutmose II), and built an even more magnificent funerary temple for herself at Deir el-Bahri. Her tomb complex consists of tiered colonnades (rows of columns) and two long, sloping causeways (one formerly lined with sphinxes), which may have suggested her spiritual ascent after death. At the ends of the second colonnade, she built shrines to Anubis, the god of the underworld, and Hathor. Behind the upper colonnade were temples to Hatshepsut herself and her father as well as to the chief gods Amun, the king of the gods, and Re, the god of the solar disk. These two eventually merged into one god, Amun-Re or Amun-Ra.

Hatshepsut was called “his majesty” and commissioned male-like images of herself like the Sphinx in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. By most counts, Egypt had only four queens in its 3,000-year history, so perhaps Hatshepsut needed such images simply to survive in a man’s world. She was buried in the Valley of the Kings.

Akhenaten and Egyptian family values

The 18th-dynasty pharaoh Amenhotep IV (1352 B.C.–1355 B.C.) launched a new monotheistic religion in Egypt, built around the sun god Aten (a variation of the sun god Re).

Amenhotep IV shut down the temples of competing gods, especially Amun, whose priests were powerful and tried to prevent the new religion from taking root. The pharaoh changed his name from Amenhotep, which means “Amun is satisfied,” to Akhenaten, meaning “It pleases Aten.” Then he moved the capital from Thebes, where the cult of Amun was strongest, to a new location that he dubbed Akhetaten. (The modern name of the city is Amarna.) The artists and architects that Akhenaten hired to honor his new religion created a new style of art, which is called the Amarna style by art historians.

Akhenaten ordered that open-air temples be built to celebrate the light and love of the sun god in a more natural, open setting. Honesty was of central importance in the new religion, so artists had to depict people, including the pharaoh, more truthfully — in other words, in everyday situations, blemishes and all. The statue of Akhenaten in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, for example, exposes his pot belly!

One of the best examples of the Amarna style is the family portrait of Akhenaten, his queen Nefertiti, and their three young daughters (see Figure 6-4). The youngest princess, who is still an infant, plays with her mother’s earring. Akhenaten tousles the hair of the princess in his arms while she points to the ankh (symbol of life) at the tip of a sun ray. The other princess holds Nefertiti’s hand and points toward her father, which helps to interlink the family. Intimacy between parents and children was new in Egyptian art. In this case, belief in one god seems to have encouraged more humanity.

|

Figure 6-4: Akhenaten’s family portrait brings the royal family down to earth while linking them to the god Aten. |

|

Vanni / Art Resource, NY

The sun disk (representing Aten) in the relief spreads its rays equally on the king and queen, suggesting that they are co-rulers governing a balanced kingdom under one god.

The painted bust of Akhenaten’s queen Nefertiti is the most famous female bust in Egyptian art. Her magnificent jewelry (typical of the Amarna period, in which exquisite jewelry flourished) echoes the color pattern of the band in her headdress. The queen is both idealized (the epitome of grace and elegance) and realistic. Her rounded shoulders and forward-leaning neck highlight her perfection and humanity. Her name means “the beauty that has come.”

Raiding King Tut’s tomb treasures

Akhenaten’s monotheistic experiment (only one god — Aten!) didn’t take root. It died with him.

When the new 9-year-old pharaoh Tutankhaten (which means “living image of Aten”) came to the throne, his vizier (chief minister) Ay, an old-school Amun priest, forced him to change his name to Tutankhamun, which means “living image of Amun.” The old religion was now back on track. Tutankhamun moved the capital back to Thebes and ordered many of Akhenaten’s outdoor temples and other innovations to be destroyed. Tutankhamun’s own death mask, made only nine years later (see the color section), shows that most of the old formality and rigidity made a comeback after Akhenaten’s death.

Tutankhamun, by the way, is the only pharaoh with a nickname. He has been popularly known as King Tut ever since Howard Carter discovered his intact tomb in 1922. His was the only king’s tomb that hadn’t been ransacked by grave robbers. It revealed the full cornucopia of Egyptian wealth and splendor and included a golden throne, four golden chariots, precious jewels, a casket of pure gold, statues of gold and ebony, and on and on. You can see why grave robbing was big business in Ancient Egypt!

Admiring the world’s most beautiful dead woman

Tombs weren’t simply covered with hieroglyphic spells. They were also elaborately painted, some with depictions of daily life that the dead could observe, but no longer participate in. The most common images were those of gods protecting the deceased. The most elaborate surviving tomb is that of Nefertari, Rameses II’s favorite wife (he had half a dozen wives, as well as countless concubines) in the Valley of the Queens. In vibrant colors, Gods escort the lovely Nefertari on her journey through the afterlife. The tomb also features a creation myth and stories of resurrection (see the color section).

Mummy slaves

Pharaohs were also buried with mummy slaves called ushabtis, which were simply statuettes. Their job was to perform work details such as brewing beer or baking bread so that the pharaoh could lead an afterlife of leisure. The ushabtis even had a script: “If the deceased is summoned to do forced labor, ‘I will do it, here am I!’”

Mummy armies also accompanied New Kingdom pharaohs in case they ran into any underworld enemies in the hereafter. (These mummy armies were probably the inspiration for the powerful skeletal soldiers in the recent mummy movies The Mummy and The Mummy Returns.)

Decoding Books of the Dead

In the Old Kingdom, pyramid texts — which included resurrection spells, charms, passwords, and prayers — were inscribed on pyramid walls. They were used to resurrect pharaohs. During the New Kingdom, similar spells were published in papyrus scrolls called Books of the Dead, which were readily available. Now anyone who could read could be resurrected.

But New Kingdom resurrection came with a hitch. The books weren’t cheap, and you had to be good to be resurrectable.

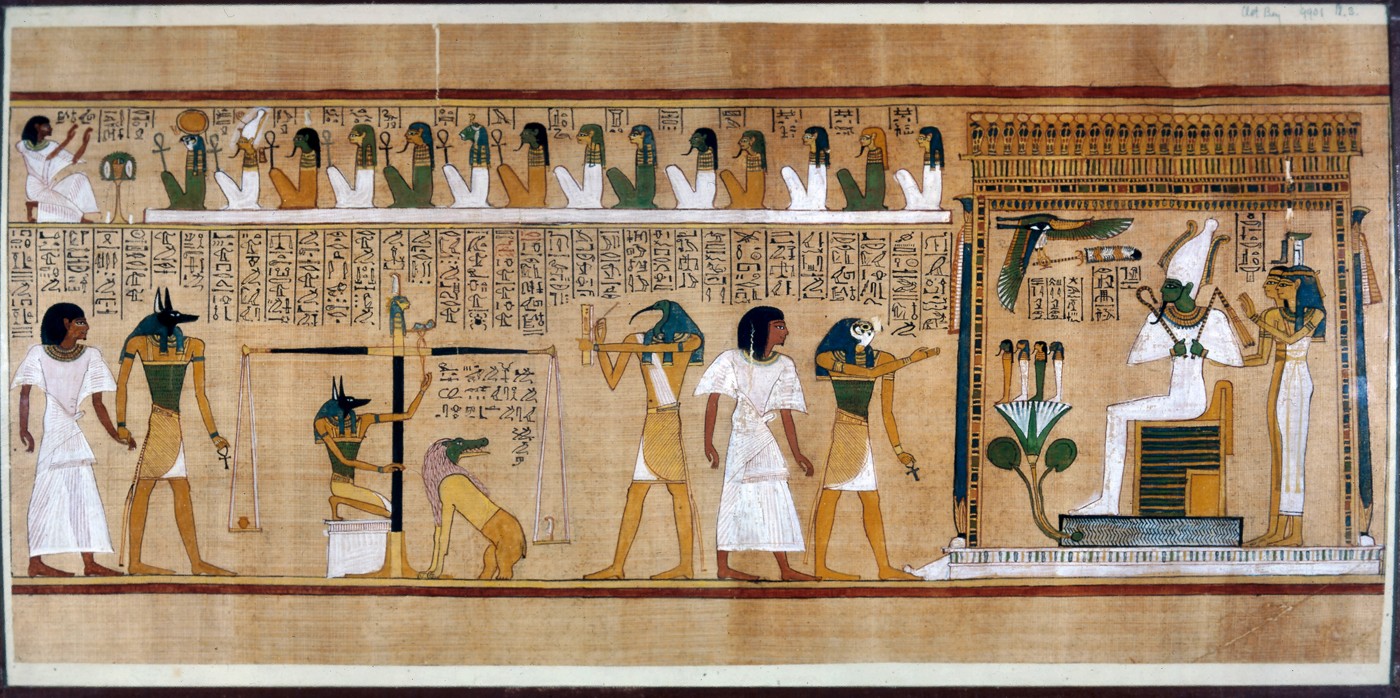

Although books of the dead were individualized for the owner, they all include a goodness test called the weighing of the heart (see Hu-Nefer’s Book of the Dead in Figure 6-5 — Hu-Nefer is an otherwise unknown man who lived during the 18th dynasty).

|

Figure 6-5: This nar- rative scene from the Book of the Dead illus- trates the weighing-of-the-heart ritual, the Egyptian version of the Last Judgment. |

|

© British Library / HIP / Art Resource, NY

Anubis, the jackal-headed god of the underworld, leads Hu-Nefer’s ka (soul) to the judgment scales. In his right hand, Anubis holds an ankh, the symbol of life. Things look hopeful for Hu-Nefer. At the scales, Anubis shows up again, this time to weigh the heart, which is contained in a jar on the left scale. The feather of truth (symbol of Maat, the goddess of truth) rests lightly on the right-hand scale. The heart had to be very light not to outweigh a feather! The court reporter, ibis-headed Thoth, records the weight while a monster named Ammit watches greedily. If the heart is heavy, Ammit gets to eat it. But on this occasion, Ammit goes hungry. Hu-Nefer moves on to the next stage.

The hawk-headed Horus leads Hu-Nefer’s ka to the temple of Osiris to face a second test. To be admitted into paradise, Hu-Nefer must recite secret prayers to Osiris that he memorized while alive — or he could have had the prayers inscribed on his coffin lid if his memory wasn’t up to snuff. Inside Osiris’s temple, Hu-Nefer encounters the four miniature sons of Horus standing on a lotus blossom, a symbol of resurrection. ( Remember: These are the guys whose heads cap the jars that contain the deceased’s organs.) Maat, the goddess of truth, soars overhead, guaranteeing that Hu-Nefer’s heart is light. Behind Osiris are his wife, Isis, the goddess of life, and sister-in-law Nephthys, goddess of decay.

Too-big-to-forget sculpture

Rameses II, who ruled Egypt for 67 years and supposedly sired 100 children, had a pharaoh-sized ego. This 19th-dynasty pharaoh (1304 B.C.–1237 B.C.) wanted to be remembered — maybe he feared he’d get a bad rap from the Bible, if indeed he was the “Pharaoh” of Exodus. In any case, Rameses erected colossal monuments to himself throughout Egypt, especially at Abu Simbel, Karnac, and Luxor, the temple districts near Thebes. Four 65-foot statues of Rameses guard the entrance to his massive temple in Abu Simbel where he could be worshipped as a god. Smaller statues of family members and his chief queen, Nefertari, hover around his knees.

Rameses II also used art as political propaganda. He barely survived the Battle of Kadesh against the Hittites, yet he touted it as a great victory on a war monument.

Though they are monumental, Rameses’s temples are not always great art. The execution seems coarse when compared to earlier temples. Maybe Rameses was in a hurry and forced his artists to streamline their work, leaving out details, so they could move on to their next project — another monument to him.