Chapter 10

Mystics, Marauders, and Manuscripts: Medieval Art

In This Chapter

Tracing the squigglies in illuminated manuscripts

Tracing the squigglies in illuminated manuscripts

Reading a tapestry that isn’t a tapestry

Reading a tapestry that isn’t a tapestry

Tracking medieval developments in architecture

Tracking medieval developments in architecture

Peering into the medieval world of painting and sculpture

Peering into the medieval world of painting and sculpture

Reading a tapestry that is a tapestry

Reading a tapestry that is a tapestry

When Rome fell, western civilization’s lights went out — sort of. The Western Empire’s collapse unleashed political chaos and caused a cultural blackout throughout Western Europe. The barbarian tribes that broke the back of the empire — including the Vandals, Visigoths, Franks, and Lombards — now fought each other, grabbing land on one frontier while losing it on another. With so much warfare, who had time for art, architecture, or theater? The Middle Ages began with the fall of Rome and continued until the Renaissance or cultural rebirth in 1400 — approximately a 1,000-year stretch.

For centuries, scholars called the entire period the Dark Ages, meaning the light of knowledge that was the hallmark of classical Greek and Roman culture had been doused. But as 19th-century researchers learned more and more about the second half of the Middle Ages, they realized that it wasn’t as dark as they’d once thought. The 12th century, for example, had a kind of mini-Renaissance, an appetizer for what was to come in the 15th century.

So scholars scaled back the Dark Ages by about 400 years, dubbing the brighter part (A.D. 1000– A.D. 1400) the Middle Ages, while stigmatizing the earlier era (A.D. 500– A.D. 1000) as the Dark Ages.

Today, scholars recognize that the scaled-down version of the Dark Ages has some bright spots, too. So they call the entire 1,000-year era the Middle Ages or the Medieval period, while quietly acknowledging that the first part is “dimmer” than the second. Bottom line: It was harder to get an education, see a play, or get your teeth fixed in the 8th century than it was in the 13th.

In this chapter, I shed some light on the entire era, from manuscripts to tapestries and Gothic architecture, sculpture, and painting.

Irish Light: Illuminated Manuscripts

The knowledge accumulated over 1,300 years (from 800 B.C. to A.D. 500) in Greece, Alexander’s Hellenistic empire, and Rome didn’t suddenly disappear with Rome’s demise — it went into hiding in monasteries scattered across Europe. The light of learning burned brightest in the hushed and secluded monasteries of Ireland.

St. Patrick converted the Irish to Christianity in the first half of the 5th century A.D. — just a couple decades before the fall of Rome. Because Ireland had never been absorbed into the Roman Empire, it remained almost completely independent of Roman traditions, including Roman religious and art traditions. The Irish Celts developed their own breed of Christianity and their own style of religious art. The popes didn’t have much say in Ireland until the 12th century when England conquered it and imposed both English and papal law on Irish kings and bishops.

After Ireland’s conversion, the Irish didn’t build lots of churches as other Christian countries did. They erected lots of monasteries instead, which evolved into great centers of learning. In monastery workshops called scriptoria, Irish monks copied all the manuscripts they could lay their hands on — including Latin versions of the Bible, writings of the Church Fathers, and classical texts.

Between about 600 and 900, the monks distributed these books throughout Europe as part of their mission to Christianize the world. This network of monks spread knowledge around like a traveling university, founding branch schools in Britain, France, Switzerland, Germany, Austria, Italy, and even Iceland.

In the following sections, we exam early Irish and Hiberno-Saxon illuminated manuscripts.

Browsing the Book of Kells, Lindisfarne Gospels, and other manuscripts

The Irish monks developed a unique style of manuscript illumination, freely borrowing elements from their pagan past, like entwined animals and knotted lace patterns. The new style that they developed is called Hiberno-Saxon.

The greatest example of the mixed Irish and English style is the Lindisfarne Gospels (see the color section). Notice how the detailed interlacing is similar to the Book of Kells, a purely Irish illuminated manuscript.

The greatest two illuminated manuscripts that are strictly Irish in style are the Book of Durrow (c. 700) and the Book of Kells (early 9th century). The Book of Kells was probably created between 803 and 805, primarily in an Irish monastery on the tiny island of Iona off the coast of Scotland. Vikings attacked the island first in 795, then in 802, and again in 805. The surviving monks fled, taking the unfinished Book of Kells with them to the town of Kells, 39 miles outside of Dublin.

The image of the Lindisfarne Gospels in the color section and the Book of Kells image referred to in the appendix show the opening page of the Gospel of Matthew. The large stylized initials, XPI, are the first three letters of Christ’s name in Greek — chi, rho, and iota. This trinity of letters was often used in the Middle Ages as a monogram to represent Christ. The rest of the text is in Latin.

The three stylized letters on the Book of Kells page (and to a lesser extent in the Lindisfarne example) partially frame large decorative wheels, which in turn frame smaller wheels that circumscribe even smaller wheels. The whole design has the feel of a system of intermeshing gears made out of pinwheels. The curved and angular shapes meld to form a perfect visual harmony. The overall impression is both wild and controlled. As you lose yourself in the interwoven patterns of the design maze, figures jump out at you: The head of a man grows out of the curling stem of the letter P; three golden-winged angels peer at you from the left edge of the X; and a pair of cats crouch on the bottom- right scroll of the same initial, eying two mice who heretically nibble a communion host. Two “big mice” ride the cats’ backs, teasing them.

Book curses

Before copyright laws, monks used book curses to protect books, not from potential plagiarists but from book bandits. The gold used in illuminations and the rarity of books made them a great temptation to thieves. The scribe usually wrote his curse in the colophon (the author’s inscription on the back page of the book). Here’s a typical medieval book curse:

This book belongs to the Abbey of St. Mary in Arnstein, which, if anyone should take away, may he die surely by being cooked in a pan, have the falling sickeness and fevers draw near him; may he be hung up and twisted around. Amen.

Drolleries and the fun style

In the 12th and 13th centuries, the first European universities emerged in Bologna and Padua, in Italy; in Paris and Montpellier, in France; in Oxford and Cambridge, in England; in Salamanca, Spain; and in Lisbon, Portugal. Students needed books, and monasteries couldn’t meet the demand. So bookmakers called stationers sprang up in university towns. To satisfy an increasingly secular (nonreligious) market, stationers produced new types of books:

Herbals: Books about plants and their medicinal uses

Herbals: Books about plants and their medicinal uses

Bestiaries: Collections of fables, stories in which animals act like people

Bestiaries: Collections of fables, stories in which animals act like people

Books of Hours: Devotional books for everyday people

Books of Hours: Devotional books for everyday people

Books of Secrets: Volumes of love potions, remedies, and even spells to prevent people from talking behind your back

Books of Secrets: Volumes of love potions, remedies, and even spells to prevent people from talking behind your back

With a widening public, books had to entertain, too. In about 1240, a new “fun” style emerged in Paris and soon spread across France and England. It featured whimsical, hybrid creations called drolleries or grotesqueries: a nun with the body of a platypus, a mole-headed priest, a pigeon-footed knight with insect wings and a serpent’s tail. These grotesqueries sometimes peek over the borders of the page to eavesdrop on your reading.

Creative book illuminators also braided flowers and foliage with the writhing tails of dragons and serpents or the tendril-like necks of exotic birds. Drolleries were the rage for about 250 years.

Charlemagne: King of His Own Renaissance

On Christmas Day in the year 800, the Roman Empire made a comeback — or so people thought. Pope Leo III crowned Charlemagne Holy Roman Emperor before cheering crowds shouting “Emperor!” and “Augustus!” Between 768 and 800, Charlemagne had conquered almost all of Western and Central Europe. It seemed he’d resurrected the Roman Empire.

Charlemagne wasn’t content just resurrecting the political and geographical side of the Western Empire — he wanted to launch a classical-culture rebirth, too. The rebirth he fostered is called the Carolingian Renaissance (A.D. 775– A.D. 875); it was another mini-Renaissance before the big one in the 15th century. Charlemagne encouraged monasteries and churches to operate schools, copy manuscripts, and develop a universal calligraphic script. To that end, he invited scholars from Ireland, England, Spain, Italy, and Gaul (France) to his capital in Aachen. One of the scholars, Alcuin, invented a new easier-to-read script called the Carolingian script, which soon became the universal standard in Europe.

Weaving and Unweaving the Battle of Hastings: The Bayeux Tapestry

In 1066, William the Bastard, the duke of Normandy, got a new name: William the Conqueror. All he had to do to shed his nasty nickname was conquer England. After overrunning the Saxons at the Battle of Hastings, no one called William “the bastard” again. His new name concealed his illegitimacy. (William’s mother was a commoner’s daughter whom his father, Duke Robert I of Normandy, never married.)

After Will grabbed the English throne, his half-brother Bishop Odo commissioned a Saxon artist to celebrate William the Conqueror’s victory on cloth. The result is the 231-foot-long Bayeux Tapestry, which chronicles the Battle of Hastings and events leading up to it from a Norman point of view.

Providing a battle blueprint

At the Battle of Hastings, William and his forces faced the newly crowned English King Harold and his veteran Saxon troops called housecarls. Harold had been underking of England for 13 years, second only to King Edward the Confessor. When Edward died, several men contended for the English throne, including his Norman cousin William the Bastard and Harold Godwinson, the underking. Edward the Confessor is said to have thrown his support to Harold on his deathbed. The English barons proclaimed Harold king. But William the Bastard insisted that the king had promised him the throne several years earlier. The tapestry illustrates why William believed he was the legitimate heir, and how William’s Norman cavalry (supported by knights from throughout Europe) defeated Harold’s army in a vicious ten-hour battle that changed English and world history forever.

Portraying everyday life in medieval England and France

The Bayeux Tapestry is one of the only surviving secular artworks of the period. As such, it offers a wealth of details about medieval life in England and France. It reveals medieval customs, armor, weaponry, and war craft; it also tells us what people ate, and how they dressed and wore their hair (see Figure 10-1). Turns out, the Normans shaved the backs of their heads and the Saxons had early Beatles-style haircuts and handlebar mustaches. In Figure 10-1, the Normans feast before going into battle. Notice the men on the left use arrows to skewer cooked chickens. Another man blows the dinner horn in the ear of the man on his left. To the right, dinner has ended and William, his half-brother Bishop Odo, and his brother Robert plan the battle (illustrated in the next scene in the tapestry).

|

Figure 10-1: The scene from the Bayeux Tapestry depicts the feast before the battle. |

|

Erich Lessing / Art Resource, NY

Peddling political propaganda

Art is sometimes used as propaganda, and the Bayeux Tapestry appears to be an example of this. The Bayeux Tapestry may be Norman propaganda, designed to justify a foreign duke’s conquest of England. One episode in the tapestry shows Harold’s coronation. At the left of the newly crowned king stands Stigand, the archbishop of Canterbury, to anoint the king and legitimize the proceedings. But Archbishop Stigand wasn’t legitimate himself — he’d been excommunicated by Pope Nicholas II, but he still had his job. He refused to resign. According to Saxon sources, Stigand didn’t even attend Harold’s coronation — Harold wasn’t about to let an excommunicated archbishop crown him. Instead, the Archbishop of York performed the ceremony, but he doesn’t appear anywhere in the tapestry’s coronation scene. The reliable English monk and chronicler Florence of Worcester (1030–1118) wrote:

When [King Edward the Confessor] was entombed, the underking, Harold, son of Earl Godwin, whom the king had chosen before his demise as successor to the kingdom, was elected by the primates of all England to the dignity of kingship, and was consecrated king with due ceremony by Ealdred, archbishop of York, on the same day.

Including the excommunicated bishop in the tapestry was a vital piece of propaganda for William. It helped him justify his claim and won him papal support before the conquest. In fact, Pope Alexander II gave William the papal banner to carry into battle and a ring containing a relic of St. Peter. This recast William’s war of aggression into a holy crusade in the eyes of many contemporaries. William won the PR war before the battle even started.

Making border crossings

Some scholars believe the borders of the Bayeux Tapestry are merely a decorative frame, like the margins of an illuminated manuscript. Others think they tell the losers’ side of the story in code — after all, a Norman (Bishop Odo, the half-brother of William the Conqueror) commissioned the design. But most scholars believe an Anglo-Saxon artist designed it and Anglo-Saxon needleworkers carried out the work. Obviously, the designer had to report the story that Bishop Odo recounted in the main sections of the tapestry. But he appears to have had a free hand in the borders. Did he sneak in Anglo-Saxon propaganda to counter the Norman view of history? If so, he had to be secretive about it. William didn’t like negative publicity.

Some of the border areas contain Latin fables — animal stories with morals — by the 1st-century writer Phaedrus. The bad behavior of the animals in these “cartoons” may mirror the actions of some of the Normans in the main body of the tapestry; they may hint at an alternative interpretation of events. Scholars are still trying to extract the meanings of the border designs.

Romanesque Architecture: Churches That Squat

Viking raids petered out in the mid-11th century, probably because most Scandinavian states had been Christianized. Europe was safer than it had been in centuries. Trade picked up and the standard of living rose through- out Europe.

During this relatively peaceful period, towns and cities groomed themselves, launching ambitious building projects on a scale Europe hadn’t seen since the fall of Rome. Naturally, they turned to Rome for inspiration. They didn’t have to look far. The Roman Empire left its stamp everywhere. Aqueducts, triumphal arches, and other Roman structures peppered the continent. The inventors of the new style borrowed the Roman arch, barrel-vaulted and groin- vaulted ceilings (see Chapter 8), and the solid masonry walls and ceilings you can see in Roman arenas (amphitheaters). Before this time, medieval church roofs were constructed of wood, but they caught fire easily in the candlelit world of the Middle Ages. The new style with vaulted stone roofs is fittingly called Romanesque. (The inventors of the new style didn’t make up this name — art historians did, in the 19th century.)

The Romanesque rage was also inspired by religion. The 10th through 12th centuries were the great age of pilgrimages to Jerusalem, Rome, and Santiago de Compostela in northwestern Spain. The many arteries to Santiago naturally passed through France. Hundreds of thousands of pilgrims traveled these roads annually on their way to Santiago. Traditional churches were too small to hold them. To meet the growing tourist traffic, large “pilgrimage churches” were built on the roads to Santiago. But the style spread beyond the Santiago route into Germany, Italy, and England. The French monk-chronicler Raoul Glaber (c. 985–1047) said, “It was as if the whole earth . . . were clothing itself in a white robe of churches.”

St. Sernin

One of the grandest Romanesque cathedrals is the pilgrimage church of St. Sernin in Toulouse, which honors the first bishop of Toulouse, Sernin, who was martyred on the spot. According to local tradition, Sernin was tied to the tail of a wild bull and dragged to his death. The name of the street in front of the church is Rue du Taur, which means “Street of the Bull.” Built between 1060 and 1118 on the Road of St. James, St. Sernin is the largest Romanesque cathedral in Europe. This roomy structure was made to handle crowds.

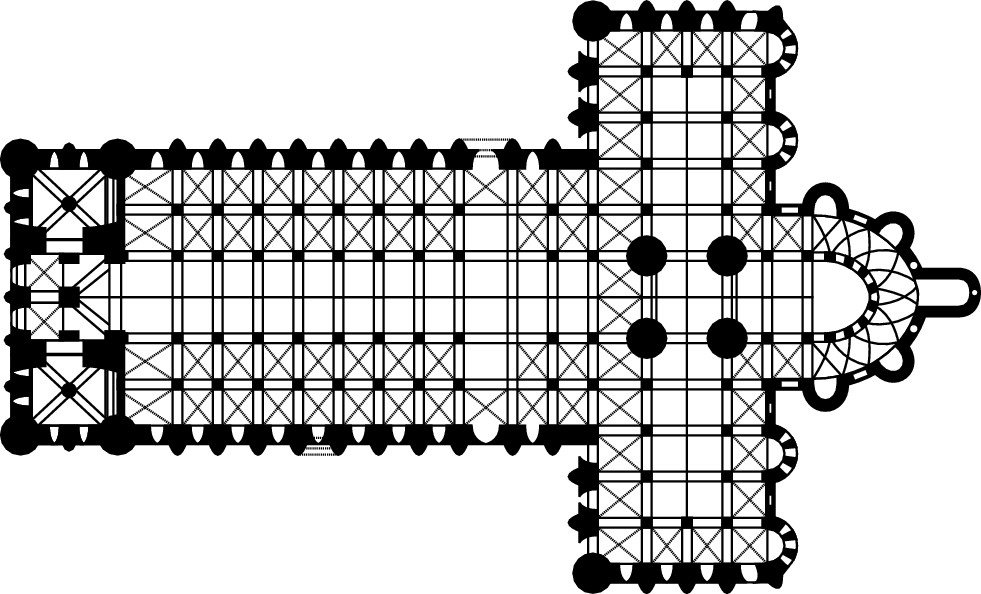

Like most Romanesque churches, St. Sernin has a cruciform or cross-shaped structure (see Figure 10-2). The tower that rises from the center or heart of the cross suggests Christ’s resurrection. Small semicircular chapels bud out of the apse (east end) of the cathedral and serve as repositories for holy relics. The biggest change from earlier church designs is the addition of an extra aisle wrapping around the nave and altar. This ambulatory (walk-around) allowed pilgrims access to the relics without disturbing mass (held in the nave). The church became a round-the-clock pilgrimage destination while still holding masses, weddings, funerals, and other services.

|

Figure 10-2: The cruciform, or cross-form, is the traditional shape of medieval cathedrals. |

|

St. Sernin’s most impressive feature is its tunnel-like nave (see Figure 10-3), the area that begins on the west end of the cruciform church. The two-story-high nave is topped by a barrel-vaulted ceiling whose weight is transferred from the arches to the piers or square pillars, which have to be very thick to hold it up. The two levels of arches on the sides help open up the space, while harmonizing with the tunnel of ribs (ceiling arches) at right angles to them. The long barrel vault has an Emerald City, Wizard-straight-ahead feel, and leads you irresistibly toward the altar.

Because of the enormous weight of the stone ceiling, the cathedral walls had to be thick. Large windows reduce the wall area, and wall area is needed for support, so Romanesque cathedrals had to have small windows.

Durham Cathedral

William the Conqueror brought the new Romanesque style to England. He’d promised Pope Alexander II that he would reform the Anglo-Saxon church of England along papal lines (and eliminate Irish Celtic influences) if he defeated Harold. Building new churches was part of his reform package. The huge and impressive structures showed the Saxon majority that their church had been Romanized and was now under the authority of the pope. The building projects continued after his death in 1087. Durham Cathedral, the masterpiece of Norman architecture, was built in 1093, during the reign of William the Conqueror’s son, William II, on the contentious border between England and Scotland. It took only 40 years to complete the gigantic structure, which was breakneck speed in those days. The constant threat of Scottish invasions must have inspired the builders to work fast.

|

Figure 10-3: The nave or parishioner area of St. Sernin had to be large to accommo- date the endless stream of medieval pilgrims on their way to the shrine of St. James in Santiago de Compostela, Spain. |

|

Scala / Art Resource, NY

Durham’s basic structure is similar to St. Sernin’s (see the preceding section). But it also has some new architectural elements. Whereas St. Sernin’s nave is two stories high, Durham’s is three. Large windows let light stream in from the top level. The nave is wider, and the larger nave arches open up the space even more than St. Sernin.

The contrasting pillars — compound piers (clusters of columns) and cylindrical columns — add variety and interest. The biggest difference is the ceiling, which features a new vaulting system called a ribbed groin vault with pointed instead of round vaults. Two modified barrel vaults are spliced together at right angels in this ceiling. Another way to look at it is that the ceiling is comprised of two overlapping barrel vaults, neither of them centered. This structure allowed builders to use thinner materials to make the sections of ceiling between the ribs. With a lighter ceiling, the architect was able to cut larger holes in the walls for windows. Durham helped pave the way for the innovative arches and vaults of Gothic architecture.

Romanesque Sculpture

Instead of a welcome mat, reliefs of the Last Judgment grimly greet visitors to Autun Cathedral and the Basilica of Ste-Madeleine Cathedral of Vezelay (see Figure 10-4). Most churches displayed scenes of the Last Judgment on the interior back wall of the nave (above the exit) so that, on their way out, people would be reminded of the price for committing sin. Why these two pilgrim churches on the Road of St. James chose to put such a menacing story at their entrances remains a mystery.

|

Figure 10-4: The tym- panum over the entrance doors of the Basilica of Ste-Madeleine, a pilgrimage church in Vezelay, depicts a medieval vision of the Last Judgment. |

|

Jesse Bryant Wilder

Nightmares in stone: Romanesque relief

The front-door Last Judgment relief at the Basilica of Ste-Madeleine appears on the tympanum (the half-moon-shaped stone above the door also known as a lunette, from the word lunar).

Christ dominates the scene by his placement and exaggerated size (with respect to the other figures). His stylized expression of openness invites everyone to come to him and to enter the church.

However, on the sides of the top and middle registers, four angels blow the trumpets of the Last Judgment. The top register represents heaven, the middle represents life on earth, and the bottom level is reserved for the dead.

Notice that the angels on the top level sound their trumpets to those on earth, while the angels on the middle band blow their horns to waken the dead. On Jesus’s left (the viewer’s right), an Angel and devil operate the judgment scales (compare this to the Egyptian “weighing of the heart” in Hu-Nefer’s Book of the Dead in Chapter 6). On the viewer’s far right, a demon, representing the mouth of hell, swallows the damned. Just below the scales, a devil lifts one of the dead up to be weighed. On the other side of the bottom band, children cling to an angel, hoping to enter heaven. Above them in the land of the living, a similar scene plays out. Some people poke their heads out of their windows to check out Judgment Day.

Such scenes must have encouraged many people to mend their ways.

Roman sculpture revival

Since the fall of the Roman Empire, sculptors had virtually stopped making large-scale sculpture in the round. Romanesque artists revived the tradition, but in their own way. The earliest examples of large-scale sculpture appear on the Road to Santiago in southwestern France and northern Spain. Perhaps they were inspired by ruins of free-standing Roman sculptures. The Apostle, carved in about 1090 for the pilgrim church of St. Sernin in Toulouse, is reminiscent of Roman statues, even though he’s stuck in a niche (not free-standing). The solidness of the statue, the cut of and folds in his garment, and his expression and stance look like a simplification of a Roman statue like the Augustus Primaporta (see Chapter 8).

Crusades: A Middle Ages crisis

The first three Crusades (1095, 1147, and 1189) were organized to “rescue” Jerusalem from its Muslim conquerors, guarantee the safety of Christian pilgrims journeying to the Holy Land, provide land and booty to landless second sons of nobles (and third sons), unite Christendom under the pope’s authority, defend the Byzantine (Orthodox Christian) Empire from Muslim incursions, and end the schism (separation) between the Eastern and Western churches.

None of these goals was achieved over the long term. The First Crusade did reach and conquer Jerusalem in 1099, mercilessly massacring the Muslim and Jewish residents, and even the women and children. Crusader states (also called Latin states) were established in Jerusalem, Antioch, Tripoli, and Edessa. But within 88 years, the Muslims reconquered Edessa, Tripoli, and Jerusalem. Antioch fell in 1268.

The great wave of Arabic contributions to Western culture

The Crusades and Reconquista (Spanish wars to eject the Islamic Moors from Spain) brought Western Europeans in contact with the far more advanced cultures of the East (Byzantium and the Islamic world). This contact changed the West forever. It led to increased trade with the East, stimulating European economies and the development of money and banking. It breathed new life into art, literature, music, and architecture and spawned a new inquisitiveness about the natural sciences.

Islamic translators in Baghdad, Iraq, and Córdoba, Spain, translated into Arabic all the surviving works of classical Greece, as well as works of Indian literature written in Sanskrit. Later these works were translated, often directly from the Arabic, into Latin, helping to keep the flame of classical knowledge alive. Without the Arabic translations, some Greek masterpieces would have been lost forever.

The influence of the two greatest medieval Arab thinkers, Avicenna (981–1037) and Averroes (1128–1198), was enormous. Avicenna’s Canon of Medicine, which was taught in European universities for about 500 years, is the foundation for western medicine. Books by Averroes, who argued that reason was more important than faith in the quest for truth, were taught in Europe until the 17th century. His famous commentaries on Aristotle influenced the leading medieval philosophers, including Albertus Magnus and St. Thomas Aquinas. Dante and Chaucer praise both men in the Divine Comedy and Canterbury Tales, respectively.

Relics and Reliquaries: Miraculous Leftovers

As modern rock fans might trek to Graceland to tour Elvis’s home or see one of his Vegas jumpsuits, medieval Christians journeyed hundreds and even thousands of miles to be close to the bones or belongings of saints. They believed some of a saint’s virtue remained in his bones or clothes after death. This leftover virtue was supposedly powerful enough to produce miracles. The most potent relics (the bones and clothes) could purportedly protect entire kingdoms.

To protect relics, Romanesque-era artists preserved them in sealed, often silver-gilt reliquaries that resembled the relic: arm reliquaries for arm bones, foot reliquaries for feet, even head reliquaries for heads. In this way, pilgrims knew what body part they were worshipping without actually seeing it. In later centuries, peepholes were added so pilgrims could glimpse the bone or body part. After walking hundreds of miles, most people wanted to see more than a pretty reliquary.

Late Gothic reliquaries make it even easier to see the relic, often by placing it in a carved rock-quartz casing.

Gothic Grandeur: Churches That Soar

Abbot Suger is credited with being the inventor of Gothic architecture (which in the Middle Ages was known as “the French Style” or the “Modern Style”). Yet he wasn’t even an architect. How did he do it?

To answer that question, you need to know a little bit about feudalism. Feudalism is a sociopolitical system in which a powerful man like a king (a lord) grants land (a fief) and his protection to a less powerful man (a vassal). In exchange, the vassal pledges his loyalty and military service to his lord. A lord might have 100 or 200 vassals (dukes, counts, viscounts, barons), who in turn have their own network of vassals. At the bottom of this social scale were serfs, peasants who were attached to the land as if they were part of the property.

Feudalism peaked in the 11th and 12th centuries. During the first half of the 12th century, the king of France ruled only the area around Paris, which is called the Île-de-France. King Louis VII was weaker than many of his vassals. To help Louis strengthen his hand and knit the rest of France to the crown, his advisor, Abbot Suger, recommended a church-and-state alliance, which would compel the counts, dukes, and bishops to submit to both God and king, at least in theory. The glue of this alliance was an architecture project, the rebuilding of the Royal Abbey Church of St. Denis, which is just north of Paris.

St. Denis is the resting place of many of France’s early kings. Charles Martel, Pepin the Short, and Charles the Bold are interred there; Charlemagne and Pepin the Short were anointed kings at St. Denis. In the 12th century, the Royal Abbey Church of St. Denis symbolized France (even more than the Eiffel Tower does today). But it didn’t look the part. Abbot Suger felt it needed a facelift, something that would announce to everyone that France was about to be reborn.

Bigger and brighter

Suger wanted the abbey church to mirror the glory of the monarchy and God. But the church was too small to reflect such a grand vision. In his book Ordinator, Suger describes “the unruly crowds of visiting pilgrims” who poured into the church on holy days to be near the relics of St. Denis or visit the tombs of France’s early kings. “You could see how people grievously trod down one another. How . . . eager little women struggled to advance toward the altar marching upon the heads of the men as upon a pavement.”

The Abbey Church’s other shortcoming was that it was too dark. Basically, Suger wanted bigger, brighter churches. He believed that God is light, so churches should be filled with radiance, not Romanesque gloom. He believed that the colored light that filters through stained glass or reflects off the gems in chalices and monstrances transports people into a mystical world of the spirit. For Suger, beautiful art was a “materialistic” highway into the spiritual world, a pathway to god.

Making something new from old parts

How big and bright could Suger make the Abbey Church of St. Denis, given its Romanesque frame? If he enlarged the windows too much, the roof would cave in. To solve the problem, Suger invited many of the best architects in Europe to Paris. Their mutual solution (Suger helped to find it, too) was to cobble together innovations from Romanesque churches like pointed arches, ribbed-groin vaults, and flying buttresses, and merge them into a single structure. No Romanesque church included all these elements.

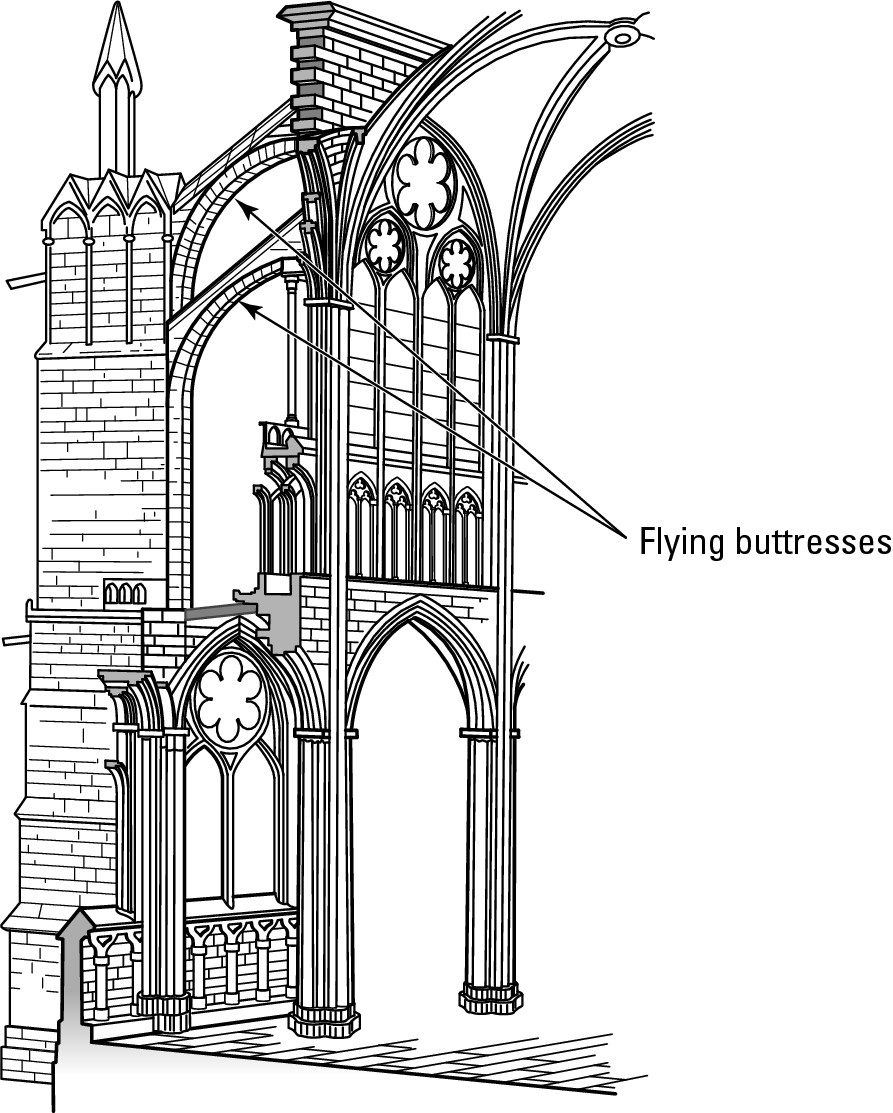

Before enlarging the windows, the designers had to redistribute the church’s weight. This was achieved with ribbed-groin vaults and flying buttresses placed against the outside walls of the church (see Figure 10-5). To understand how flying buttresses work, picture a row of strong guys or gals, each straight-arming the church, as if to hold it up. Their arms are the “semi-arches” or butts of the buttresses, and their bodies are the buttress verticals.

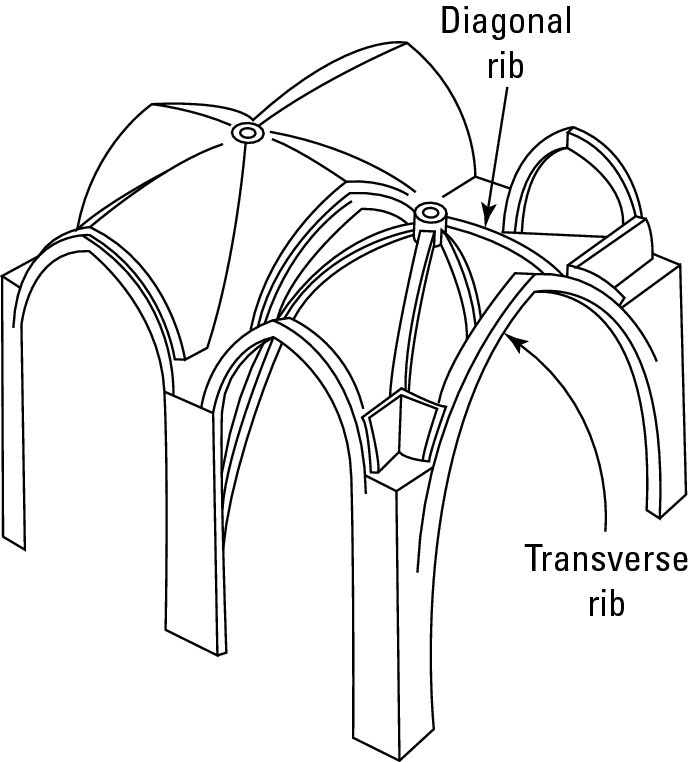

How does ribbed vaulting work? The ribs of each vault, which look like a rib cage or the inside spokes of an umbrella (see Figure 10-6), channel the weight from the vault (roof) to the walls, where the flying buttresses counter or neutralize it.

|

Figure 10-5: Flying buttresses or external supports, like those shown in this illustration, help hold up the massive roof of the Abbey Church of St. Denis, the first Gothic cathedral. |

|

|

Figure 10-6: St. Denis’s ribbed vaulting, like that shown in this illustration, transfers the weight of the roof to the external flying buttresses. |

|

Because the flying buttresses do much of the wall’s work, the walls can be opened up with large windows. For the first time in history, a monumentally large, closed building could be flooded with natural light! Suger’s achievement must have seemed miraculous.

Finishing touches and voilà!

Suger added a necklace of chapels around the east end of the church so “the wonderful and uninterrupted light of most luminous windows [could] pervade the interior beauty” of the choir and altar. (The east end of the Romanesque cathedral of St. Sernin is similarly circuited by a ring of small chapels.) Abbot Suger rededicated the Royal Abbey Church of St. Denis on June 11, 1144 in the presence of King Louis VII and his queen, Eleanor of Aquitaine.

Expanding the Gothic dream

The Gothic style spread from St. Denis to the rest of France. In 1163, construction began on Notre Dame (see Figure 10-7). Between 1170 and 1270, the French erected more than 500 Gothic churches. Among the greatest are Chartres (1194), Reims (1210), Amiens (1247), and St. Chapelle (1243–1248). During this period, architects became more daring — building taller cathedrals, streamlining the stone piers and buttresses to maximize efficiency, and reducing the walls to expanses of stained glass (see the following section, “Stained-Glass Storytelling”). The buildings become more skeletal and gravity-defying. By 1243 (when St. Chapelle was built), the walls had all but disappeared and had been replaced by acres of stained glass.

|

Figure 10-7: Notre Dame in Paris is the most famous Gothic cathedral in the world. |

|

Jesse Bryant Wilder

During the next 200 years, the Gothic style spread across all Europe and beyond. Like Romanesque, it was an international style born in France. Some of the most outstanding Gothic cathedrals are Salisbury Cathedral in Salisbury, England (1220); Cologne Cathedral in Cologne, Germany (1248); St. Stephens in Vienna, Austria (1304); St. Vitus in Prague, Czech Republic (1344). The French style stayed largely intact in most countries, with some regional variations. But in Italy, Byzantine and Roman influences greatly modified the style.

Stained-Glass Storytelling

In 1194, the city of Chartres and its Romanesque cathedral burned. The townspeople were crushed. Not only had they lost their homes and church, but more importantly, they lost their prize relic, the Sancta Camisia (the veil Mary is said to have worn when she gave birth to Jesus). Three days later, the relic turned up, undamaged. It seemed like a miracle, but in fact, when the fire started, a resourceful priest hid it in the cathedral crypt. A visiting cardinal, addressing the relieved citizens, said the recovery of the relic was a sign from Mary: She wanted a bigger church! The crowd erupted with enthusiasm. Donations soon poured in for the new cathedral. Although he was at war with France (as usual), Richard the Lionheart, king of England, let English priests collect money for the reconstruction. Not to be outdone, the French king, Phillip August, paid for the cathedral’s elaborate North Porch.

Because the cathedral was to be built in the new Gothic style, many people donated stained-glass windows. French guild workers donated 43 stained-glass windows, each guild “signing” its work with an image depicting its trade. Nobles often “signed” the windows they donated with their coats of arms. The blazonry (coat of arms) of France — the fleur de lis — is part of the elaborate pattern of the north rose window of Chartres (see the color section), donated about 40 years later by the new French queen, Blanche of Castille, the granddaughter of Eleanor of Aquitaine and the mother of St. Louis.

The kaleidoscope patterns of the rose window are an exercise in theme and variation of shape, symbol, and color. Each of the clocklike, concentric rings is comprised of 12 repeated shapes. The outer semicircles feature 12 Hebrew prophets. The postage-stamp figures in the middle ring are 12 kings of Judah. Mary and the Christ child sit in the center. Beneath the rose, five lancet (tall and narrow) windows frame Hebrew, Babylonian, and Egyptian kings, from Nebuchadnezzar to King Solomon.

Other windows and external relief sculpture tell the stories of the Bible from Genesis to the Apocalypse. In those days, the only way most people could “read” the Bible was through stained-glass storytelling and narrative relief. Thanks to Abbot Suger, windows and churches could now be built large enough to recount the entire Bible.

Most of France’s Gothic stained-glass windows were smashed during the French Revolution. The only church with most of its original stained glass is the Cathedral of Chartres; 152 of the original 186 windows survive.

Gothic Sculpture

Gothic sculpture was inspired by Abbot Suger’s innovations at St. Denis (see “Gothic Grandeur: Churches That Soar,” earlier in this chapter). Unfortunately, much of the St. Denis sculpture has been damaged. But the statues on the west portal (front doors) of Chartres were carved just one year after Suger completed St. Denis and reflect a similar style (see Figure 10-8). The statues are much more realistic than the relief carvings on the tympanum of Vezelay Cathedral (refer to Figure 10-4), even though those were carved only 10 to 15 years earlier (a decade before Suger launched the Gothic style!).

|

Figure 10-8: The jamb statues on the west portal (entrance doors) of the Cathedral of Chartres stand in a pose that is determined by the column, as if they were an extension of it. |

|

Gloria Wilder

The cigar-shaped statues (jamb or column statues) that sentinel each of the three doors were made to fit the columns, which almost appear to be their backbones (refer to Figure 10-8). Their long legs still have a Romanesque rigidity, but the clothing and faces are much more realistic. Instead of the wild, nightmarish look of the Vezelay tympanum (in Figure 10-4), these statues have a quiet dignity that befits their stature as Old Testament kings, queens, and prophets (the ones without crowns are the prophets). The west doors are also known as the royal portal.

Forty years later, during the church’s reconstruction after the 1194 fire, the Gothic style had moved even closer to Realism. The statues on the south transept doors, or south portal (see Figure 10-9), look like people you might meet on the streets of Paris or Chartres if you could beam back in time. The figures are still dignified like those on the royal portal, but their dignity no longer conceals their individuality. These figures are much nearer to being free-standing statues than their royal portal counterparts. The column supports seem like crutches that the statues could walk away from to share a draught of mead with you in a local café. The statue of St. Theodore dressed as a contemporary crusader on the left (these were carved 10 to 20 years after the Fourth Crusade in 1204) is the most naturalistic. Notice the round contours of the flesh under his left arm and the naturalistic manner in which he grips his lance.

|

Figure 10-9: The south portal statues have a much more realistic look than the older jamb statues on the royal, or west, portal. |

|

John Garton

Italian Gothic

In Italy, the transplanted Gothic or French style took on a distinctly Italian flavor. Italian Gothic cathedrals look nothing like French cathedrals. There is more than a hint of Byzantine splendor and Italian love of color in Siena Cathedral, which may be the most sumptuous church in Europe — from its inlaid marble floors, which Giorgio Vasari (the great Renaissance biographer) called “the most beautiful . . . great and magnificent pavement ever made” to the stellar beauty of its star-spangled, rib-vaulted ceiling, created to suggest heaven.

Siena Cathedral took several centuries to complete. I focus here on the Gothic part, which was built in the 13th and 14th centuries, beginning in 1215.

Like many Italian churches, Siena Cathedral has a dome and bell tower (campanile), but it lacks the soaring spires associated with the French style. What it fails to achieve in height, it makes up for in decoration. Giovanni Pisano designed the bottom half of the dazzling facade and sculpted its superb statues between 1284 and 1296 (the originals are now in the Cathedral Museum). Giovanni Pisano had assisted his famous father, Nicola Pisano, 20 years earlier in creating the cathedral’s magnificent Carrara marble pulpit. At the time, Giovanni was in his early 20s. (The top half of the facade was designed by Giovanni di Cecco, beginning in 1376.)

Pisano framed the three front doors with elaborate polychrome marbles, some of which are striped like candy canes. The columns have Corinthian-style capitals and appear to arc into the lunettes above them. The pediments above the lunettes each enclose a from-torso-to-head bust. Just above the outside pediments, Pisano sculpted the four evangelists of the gospels in pairs — Mark and Luke to the viewer’s left, Matthew and John to the right. Each apostle stands next to his animal symbol; each, except John, holds the gospel he wrote.

The interior of Siena Cathedral is a visual feast. There’s almost too much to look at. But in spite of the abundance of decoration and sculpture, it has an overarching unity. The rib-vaulted ceiling and the colonnades of arches dividing the nave from the aisles are influenced by French Gothic. Together they create a glorious architectural harmony. The inlays on the inside of the arches, the black-and-white marble piers, and the 36 busts of Christian emperors beneath the two imposing rows of 176 popes are all uniquely Italian features.

The rose window on the opposite end of the cathedral was based on a design by Duccio (see the following section).

Gothic Painting: Cimabue, Duccio, and Giotto

The knights of the Fourth Crusade (1201–1204) never reached their destination: Egypt. They got sidetracked into attacking Constantinople — their ally! The crusaders crushed the Eastern Roman Empire, which, until then, seemed eternal (though it did get back on its feet about 60 years later, and stayed on them for almost 200 more).

The one positive result of the crusaders’ occupation of Constantinople was that many Byzantine artists fled the city and emigrated to Italy, bringing Eastern cultural influences with them. Italians called this influence the Greek manner. The Greek manner mixed with the relatively new Gothic style that seeped into Italy from the north. The melding of the two gave birth to a revolutionary style of painting that paved the way for the Renaissance. This style was more than the sum of its parts. Although the component parts were French Gothic and Byzantine or Greek, the new style had a decidedly Italian flair. The three greatest masters of this new style are Cimabue, Duccio, and Giotto.

Cimabue

Madonna Enthroned by Cimabue (c. 1240–c. 1302) has many of the same generic features that Byzantine icons have. (Refer to the Virgin of Vladimir [see the appendix] and Andrei Rublev’s The Old Testament Trinity in the color section.) These features include

Standardized folds in the garments, as if they’d all been pressed by the same drycleaner

Standardized folds in the garments, as if they’d all been pressed by the same drycleaner

Gold, plate-size halos

Gold, plate-size halos

Identical poses and gestures

Identical poses and gestures

Clone-like angels

Clone-like angels

A flat, decorative background (hammered gold leaf)

A flat, decorative background (hammered gold leaf)

In other words, Madonna Enthroned has the same hand-me-down composition. But there are subtle differences. Cimabue’s faces, especially those in the bottom register, are fuller, fleshier, and much more expressive.

These differences are more pronounced in Cimabue’s Madonna in Majesty fresco (see Figure 10-10), painted for the Basilica of St. Francis in Assisi about 50 years after St. Francis’s death:

The Madonna in Majesty has an intimacy that Byzantine icons lack. Icon paintings are meant to be aloof, because they depict divine beings (saints, apostles, Christ) who might raise a hand in the viewer’s direction and make eye contact, but who remain from another world.

The Madonna in Majesty has an intimacy that Byzantine icons lack. Icon paintings are meant to be aloof, because they depict divine beings (saints, apostles, Christ) who might raise a hand in the viewer’s direction and make eye contact, but who remain from another world.

The flesh of the figures is fleshy. They’re more realistic than Byzantine icons.

The flesh of the figures is fleshy. They’re more realistic than Byzantine icons.

The painting has a gentle sadness about it that the blues and greens and Mary’s angelic prettiness sweeten. All the faces in the fresco seem to reinforce this emotion as if they had the same reaction to something that’s not visually stated in the painting. Expressive emotion is one of the unique characteristics of the new style of Italian painting (13th and early 14th centuries).

The painting has a gentle sadness about it that the blues and greens and Mary’s angelic prettiness sweeten. All the faces in the fresco seem to reinforce this emotion as if they had the same reaction to something that’s not visually stated in the painting. Expressive emotion is one of the unique characteristics of the new style of Italian painting (13th and early 14th centuries).

|

Figure 10-10: Cimabue’s serene but damaged Madonna in Majesty adorns the Basilica of St. Francis in Assisi. The fresco has undergone several major restorations. |

|

Scala / Art Resource, NY

On the right side of the painting stands a barefoot St. Francis. He is easy to identify because he bears the stigmata (wounds of Christ) on his hands and feet. Like the angels beside him, Francis looks at the viewer, almost as if he were posing for a photograph. None of them seems to notice the others.

Cennino Cennini’s craftsman’s handbook

In the late 1390s, a Florentine painter named Cennino Cennini wrote a guidebook that gave instructions in medieval painting techniques. Cennini wasn’t the greatest painter of his day, but his Handbook records time-tested methods of art making from the medieval period.

The book reveals that wood panels (oak in the northern countries, poplar in Italy) had to be installed in elaborately carved and decorated frames before the painter got a crack at them. (Duccio used frames like this to paint altarpieces.) Then a craftsman brushed the panel surface with gesso (a mixture of rabbit-skin glue and chalk) many times and afterward sanded it smooth. Next, he mixed a red earth pigment, called bole, with the glue and brushed it onto the areas where gold leaf would be applied (think extremely light, gold foil). If the craftsman placed the gold leaf directly on the tan gesso, it would look greenish and sickly; whereas, with the reddish underlayer, it glowed with a golden warmth. Next he sketched in the contours of the figures and then stamped ornate halo designs onto the gold background with special tools. Finally, he cracked a few eggs, extracted the yolks, and mixed them with tempera pigment to create the paints. Because egg tempera dries quickly, most medieval artists mixed their colors as they worked by painting tiny strokes of one color next to the dry strokes of a neighboring color, hoping that, from a distance, they would appear to mix to the desired hue of the saint’s robe or whatever they were painting.

Duccio

At first glance, Madonna Enthroned by Duccio (c. 1255–c. 1319; see the color section) also mimics Byzantine icon painting — “the Greek manner.” But on closer inspection, you can see a three-dimensionality that’s missing from icon paintings. The faces have contours, angles, areas of shadow and light, and a hint of personality. Notice that Mary’s right hand is more natural looking here than it is in Cimabue’s Madonna Enthroned. The two pairs of bare feet on the right and left sides of the painting are also fleshed out and real: They don’t wear the same size shoes.

The cloaks on the figures fall more fluidly. The contours of Mary’s right knee and leg press naturalistically through the fabric. You can see the same naturalism in the Gothic statue of St. Theodore on the south portal of Chartres (refer to Figure 10-9). These differences reflect the French-Gothic side of Duccio. In this painting, Duccio seems to have found a perfect balance between Gothic elegance and Byzantine formality. But in Italy, the scales soon tipped toward naturalism and a revival of Western Empire classicism.

Giotto

According to Renaissance biographer Giorgio Vasari, Giotto (c. 1266–1337) became Cimabue’s pupil after the older artist saw the boy sketching some grazing sheep. He recognized the 10-year-old’s talent at once. In 1550, Vasari wrote, “The child not only equalled the manner of his master, but became so good an imitator of nature that he banished completely that rude Greek manner and revived the modern and good art of painting.”

Like Cimabue, Giotto was practically a Florentine. (Both were born in the suburbs, but scholars usually label them as Florentines.) Although Giotto appears to have been Cimabue’s student (Vasari isn’t always reliable), he was a much greater or at least more original artist than his master. Apparently, Cimabue liked sticking to the Byzantine tradition as long as he could mix it with a little Gothic realism. What made Giotto unique was that he didn’t copy from others — he copied from nature.

Giotto was a great observer. He noticed life’s details and included them in his art. His religious paintings give the impression that you’re watching the actual events through a hidden camera. Some figures in his paintings turn their backs on you, as they might in real life. Others stand in front of the people around them, blocking their faces or part of their bodies from view. Byzantine artists would never do this; the formulas for icon paintings wouldn’t allow it.

Giotto’s ability to capture feeling in a multitude of situations makes his work revolutionary and refreshing. There is an emotional intensity in his frescoes that hadn’t been seen before, not only in the expressiveness of the faces, but in the dramatic lighting that bathes the figures. In The Kiss of Judas (see Figure 10-11), Giotto creates an electrifying drama, heightened by the thicket of spears, torches, and shepherd staffs, wielded by the combatants. All the explosive tension in the painting converges on the kiss, as Jesus and Judas square off.

Giotto’s paintings have a cinematic quality, especially the Arena Chapel fresco series in Padua, which is considered to be his greatest work. Instead of posing for the viewer, as if someone were about to snap their picture (as in the Cimabue and Duccio examples above), the people in the frescos look at each other directly or out of the corners of their eyes. They interact and communicate with one another instead of posing.

|

Figure 10-11: In The Kiss of Judas, Giotto dramatizes Christ’s betrayal by depicting the clash between Jesus’s supporters and enemies. |

|

Scala / Art Resource, NY

In The Flight into Egypt, notice how the Virgin Mary and the woman leading the donkey study Joseph as he guides them through the desert. The Christ child observes a woman behind the donkey who is talking to her companion. Everyone has his or her eyes on someone. The interplay of glances tells a very human story. True, the background trees look like magazine cutouts pasted onto the mountains (which also look like cutouts), but Giotto was interested in people. His painting revolution took place in the foreground, not the background.

Giotto’s people inhabit not only the same scene, like the figures in Cimabue’s and Duccio’s works, but they occupy the same psychological space. This is the first time in art that people in a painting ignore the viewer and focus on each other.

Tracking the Lady and the Unicorn: The Mystical Tapestries of Cluny

Tapestries woven of wool and silk threads and gold and silver wires were very fashionable among the rich in the 14th and 15th centuries. They hindered drafts and beautified drab castle walls. The reason so few exist today is that, in later centuries, people burned them to extract the gold and silver wires. Medieval tapestries usually recounted allegorical stories (stories in which the characters represent virtues or vices) meant to illustrate courtly love, chivalry, or religious themes.

Perhaps the most famous tapestries are the six Lady and the Unicorn tapestries, created for Jean Le Viste in the late 15th century. The tapestries now hang in the Musée de Cluny (also known as the Musée National du Moyen-Age) in Paris. The Lady and the Unicorn cycle is done in the popular millefleur (thousand flowers) style, in which hundreds of floating flowers sift through the tapestry background like confetti. The background is intended to represent a field of flowers, often populated by playful animals, but the ground is so steeply pitched that both the flowers and the animals appear to be levitating.

At first glance, The Lady and the Unicorn doesn’t seem to have a courtly love theme. There are no men in any of the six tapestries. But a male presence is implied; the Lady seems to be wistfully thinking of an absent lover. Perhaps the unicorn is a kind of stand-in for him.

Five of the Lady and the Unicorn tapestries represent the senses. Today we refer to them as “Touch,” “Taste,” “Sight,” “Hearing,” and “Smell.” The sixth and most mysterious tapestry seems to be about love and desire — yielding to it or renouncing it. The words A Mon Seul Désir (To My Only Desire) are emblazoned on the canopy of the blue tent in the center of the tapestry. In the other tapestries, the Lady wears a richly jeweled necklace, possibly a gift from a lover. In A Mon Seul Désir, she either returns or takes the necklace from her jewelry box. Is she renouncing love (putting the necklace back) or getting ready for a date (putting it on)?

In the tapestries of the senses, the Lady tames or seduces a wild unicorn. In pre-Christian legends, only a virgin can tame the erotic beast by resting its phallic horn between her breasts. This racy tale was edited in the Middle Ages. In the Christian period, only a virgin could catch and tame a unicorn (which may be why their “appearances” were so rare). Christians also believed that the animal’s horn would purify whatever it touched — dipping a unicorn horn into a polluted stream could clean the water. They further updated the legend by linking the unicorn to the Virgin Mary. In medieval art, often a unicorn is shown resting its head on the Virgin’s lap or touching her lap with its hoof, as it does in the “Sight” tapestry, shown in the color section. The infant Jesus also sat in Mary’s lap and purified whatever he touched, so unicorns became symbols of Christ’s incarnation as well.

Is the Lady who tames the unicorn a substitute for the Virgin Mary? Is she a virgin who wants to be something else or a virgin who wants to transcend the world of the senses forever? Or is she an experienced woman who wishes she could have her innocence back? Or do the tapestries represent the seasons of a woman’s life?

These are questions no one can answer, which is one reason why the tapestries still intrigue people after 500 years. Many people believe the Lady and the Unicorn tapestries are about a woman renouncing the sensual world for a contemplative or spiritual life. This was not uncommon in the Middle Ages. Many women and men retired from the world of the senses to join one of the many religious orders: Franciscans, Poor Clares, Dominicans, Carthusians.

In “Touch,” the Lady holds the unicorn gently by the horn, suggesting that she has tamed him. But there may be another level of meaning. Does holding the unicorn’s horn mean the Lady has mastered her desire or been mastered by it? Is she renouncing the sense of touch, or yielding to it? Maybe the answer is in her faraway eyes, which suggest she longs for something she can no longer have.

All the animals in the tapestry, except the monkey on the upper left, seem to serve or be controlled by the Lady. Notice that the monkey (a symbol of unruliness) is chained up. There’s no place for monkey business in the “Touch” tapestry. But in the other tapestries, he’s unleashed and sometimes behaves mischievously — sniffing a rose or chomping on a nut or morsel of candy the Lady drops.