Chapter 11

Born-Again Culture: The Early and High Renaissance

In This Chapter

Exploring Renaissance ideals

Exploring Renaissance ideals

Making sense of rationalist architecture

Making sense of rationalist architecture

Tracking vanishing points and reading narrative paintings

Tracking vanishing points and reading narrative paintings

Decrypting the visual poetry of Botticelli

Decrypting the visual poetry of Botticelli

Standing up with Donatello

Standing up with Donatello

Soaring into the High Renaissance with Leonardo, Michelangelo, and Raphael

Soaring into the High Renaissance with Leonardo, Michelangelo, and Raphael

The Renaissance is the “rebirth” or reawakening of Greek and Roman culture, which in 1400 had been dozing for almost a thousand years. What sent classical culture into hibernation? When Rome fell, many Christians turned their backs on classical culture, which they associated with paganism. For the next 1,000 years, artists focused on God and the afterlife (or depicted the horrors of hell to scare people into behaving), instead of celebrating the sensual earthly life as the Romans and Greeks had.

But the past wasn’t completely forgotten. Poets like Dante and Chaucer mentioned Greek myths on occasion, and Romanesque architecture (see Chapter 10) revived elements of Roman architecture in the 11th and early 12th centuries.

During the Renaissance, classical culture made nearly a complete comeback. Artists resurrected realism in painting and sculpture; and classical literature, history, and philosophy inspired writers from Niccolò Machiavelli to William Shakespeare and Jean Racine. Even the Greco-Roman gods reappeared, showing up in art nearly as often as Christian saints. That doesn’t mean artists converted to paganism (though some were accused of it). They became down-to-earth Christians, focusing on the here and now as much as the hereafter.

The Early Renaissance in Central Italy

Most historians believe that the city of Florence gave birth to the Renaissance in the 15th century (also known as the quattrocento, or 1400s). But the new movement had its roots in the preceding century, especially in the art of the Florentine Giotto (see Chapter 10), who had given flesh a three-dimensional look for the first time since the fall of Rome. However Giotto’s perspective was intuitive and imprecise, not mathematical; consequently, his paintings have a shallow depth of field; the figures tend to hover in the foreground.

Building on Giotto’s achievements, artists of the Early Renaissance (1400–1495) invented a precise science of perspective to give their artwork infinite depth. During the Renaissance, looking at a painting was like peering through a window at the real world, with some objects close and others far.

The Great Door Contest: Brunelleschi versus Ghiberti — And the winner is!

In a way, a door-making contest launched the Renaissance in 1401. Florence was about to be gobbled up by Milan. The power-hungry Duke of Milan had already conquered Siena (in 1399) and Perugia (in 1400). Florence was next on his hit list. The duke intended to rule all of Italy, which was a fractured “country” of independent city-states. Despite the impending danger, Florence’s leaders decided to sponsor a door-making contest instead of investing all their civic energy into strengthening their defenses.

The doors of the Florentine baptistery (the place where all citizens were baptized) were very important to Florence. Seventy years earlier, the sculptor Andrea Pisano had cast two of the baptistery doors in gilded bronze with scenes from the life of St. John the Baptist, the city’s patron saint. Now city leaders wanted two more bronze doors.

The year 1402 turned out to be a good one for Florence and the Renaissance. The Duke of Milan died of the plague, and Florence was saved. Also, the winner of the door contest was announced: Lorenzo Ghiberti. The Renaissance was under way. Three of the other seven contestants also became pioneers of the Renaissance, spreading it in other directions: Donatello, Jacopo della Quercia, and Filippo Brunelleschi.

Ghiberti’s bronze doors so dazzled Florentines that the city invited him to make two more doors. He did. The second set perfectly illustrated scientific perspective (which Brunelleschi invented) and so impressed the young Michelangelo that he dubbed them the “Gates of Paradise” (see the color section).

After failing to win the door contest, Brunelleschi gave up sculpture and became an architect. He probably made a trip to Rome not long after the contest with his friend the sculptor Donatello to study Roman architecture. Using classical models like the Pantheon and Colosseum, Brunelleschi invented Renaissance architecture, a geometrical style of grace, harmony, and openness.

The Duomo of Florence

Sixteen years after the door contest, Brunelleschi competed against Ghiberti again to design a dome for the Duomo (cathedral) of Florence. This time he won. The Duomo had a wooden roof, it needed a stone one. But the massive Gothic structure seemed too huge to cap with a stone dome. Instead of constructing a single solid mass, which would have been too heavy, Brunelleschi solved the problem by designing a double masonry shell, each reinforcing the other. (The total dome weight is over 40,000 tons!) The double shell rested on a massive drum, rather than the roof. Thanks to this ingenious method, Brunelleschi was able to construct the world’s biggest and one of its most majestic domes. The Duomo dome soars 375 feet.

Other projects soon came Brunelleschi’s way. One of his greatest achievements was his design for the ruling Medici family’s church, San Lorenzo. With its Corinthian columns, Roman arches, and classical harmony, San Lorenzo feels as much like a pagan temple as a Christian church. Because Brunelleschi used proportional ratios (possibly derived from musical ratios) and geometric shapes, the building conveys a sense of rational order, grace, and serenity.

Above all, the space conveys a sense of rational order rather than religious ecstasy, inspiring visitors to think about God rather than swoon over him.

What’s the point? The fathers of perspective

Things appear to shrink as they recede into the distance. Watch someone walking down a straight road, and eventually, she’ll disappear. But at what rate does she shrink? At a hundred yards away, how much shorter is she than she was when she was standing next to you?

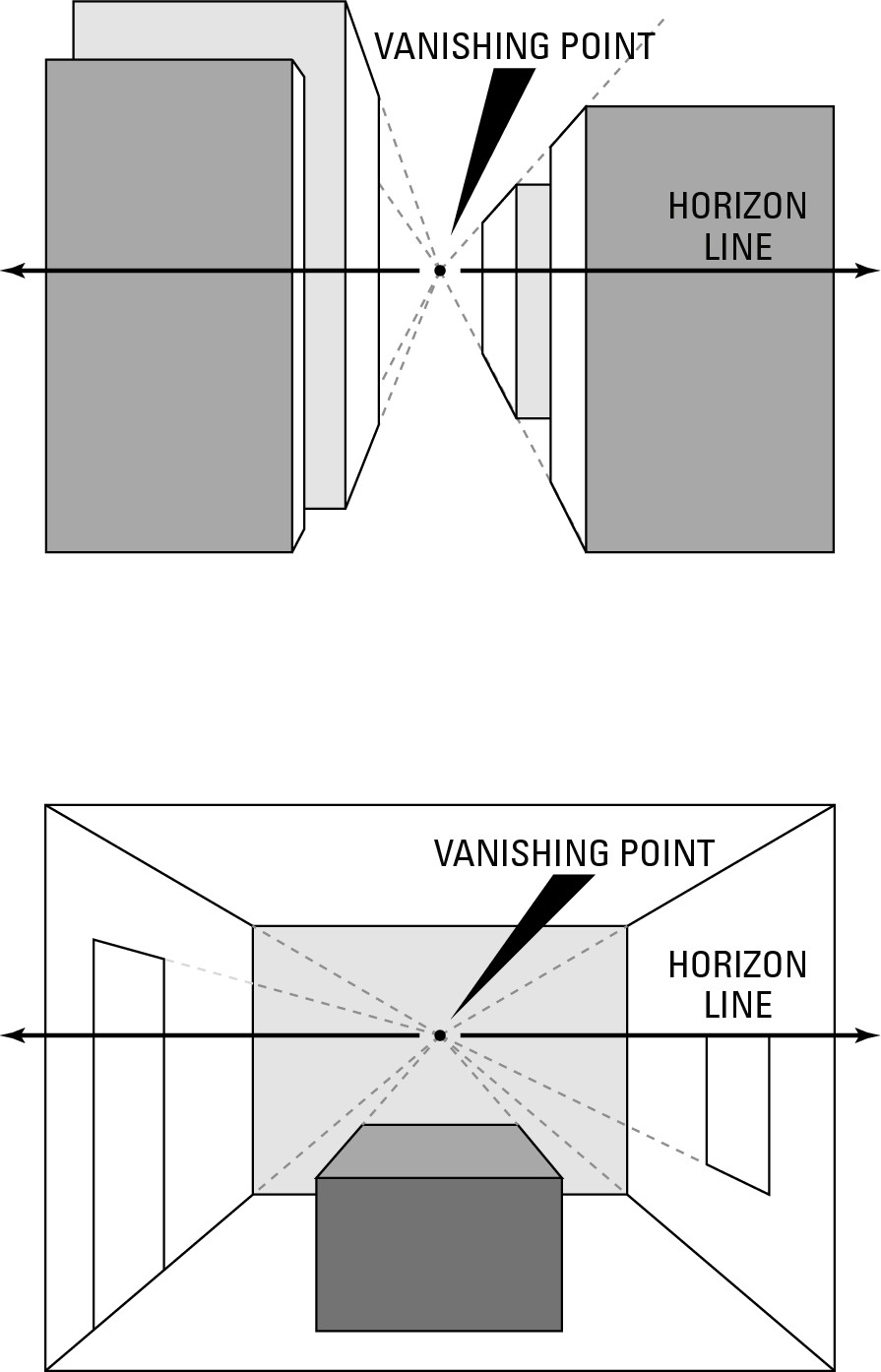

Artists had to guess until Brunelleschi invented linear perspective, which his friend Leone Battista Alberti described in his book De Pictura (On Painting) in 1435. The main feature of linear perspective is the vanishing point. You know railroad tracks are parallel, yet they appear to converge as they recede into the distance. In one-point perspective (which means perspective with one vanishing point), the lines on each side of a painting gradually converge like railroad tracks. By drawing railroad tracks from the tops and bottoms of rectangular buildings on the left and right sides of a painting or drawing, you can determine the correct height of any object between the foreground plane of the painting (the surface of the canvas) and the vanishing point (see Figure 11-1).

In the following sections, we examine the art and architecture of major Early Renaissance and High Renaissance artists and architects.

|

Figure 11-1: Linear perspective is an exact science; an object’s location determines its size. |

|

Masaccio: Right from the fish’s mouth

Masaccio (1401–1428), one the greatest painters of the Early Renaissance, was the first to apply Brunelleschi’s system of perspective to painting. At the age of 21, he was already a master. Unfortunately, he only lived six more years.

Masaccio’s greatest works may be his frescoes of the life of St. Peter in the Brancacci Chapel in St. Maria del Carmine in Florence. The painting The Tribute Money is a visual narrative with three episodes that begin in the center, move to the left, and then backtrack to the right. Only one character, St. Peter, appears in all three scenes, dressed in an orange cloak over a blue undergarment. His clothes help the viewer track his movements.

Peter’s concern about paying tribute money (taxes) prompts Jesus to say, “Go thou to the sea, and cast an hook, and take up the fish that first cometh up; and when thou hast opened his mouth, thou shalt find a piece of money: that take, and give unto them for me and thee [pay the taxes with it].”

The baffled looks on the faces of the apostles (each dumbfounded in his own way) shows the Renaissance shift in focus from God to man. Although the painting illustrates a biblical passage, Masaccio draws the viewer’s attention to the apostles’ human reaction to Jesus’s strange prediction. Pointing fingers, gestures, and stunned expressions tell the rest of the story.

Masaccio’s handling of perspective is masterful. Though the figures cluster together in the center of the painting, the ones in the rear of the group shrink convincingly, according to the laws of linear perspective. The background of gloomy gray mountains and sky, though simple, gives the painting a profound sense of depth. Your eyes can wander into the distance in his painting.

After Masaccio’s early death, painting languished in Florence.

Andrea del Castagno: Another Last Supper

For a while, it seemed Andrea del Castagno (c. 1423–1457) might fill Masaccio’s shoes as the next great Renaissance painter. But like Masaccio, he died young, at the age of 34, from the plague.

Castagno’s career started when he was a teenager. At 17, the Medici family commissioned him to paint the corpses of rebels hanged for conspiring against Medici rule. The painting has long been lost.

One of Castagno’s greatest paintings is The Last Supper on the dining hall of the convent of St. Apollonia in Florence. The Apostles have even more personality in this fresco than they do in Masaccio’s The Tribute Money. But they barely communicate; they seem to be in their own world.

Fra Angelico: He’s not a liqueur!

Fra Angelico’s real name was Guido di Pietro. His nickname, which is what most people know him by, means “Angelic Brother.” He carried the Renaissance spirit quietly and subtly into the Florentine Monastery of San Marco where he lived as a Dominican monk. With a team of assistants, Fra Angelico covered the walls of the monastery over a ten-year period (1435–1445) with frescoes of quiet beauty.

The paintings of Fra Angelico (c. 1400–1455) are prayers. They have a serene intensity — perfect for spiritual contemplation.

Even his fresco The Mocking of Christ (see Figure 11-2), in which disembodied hands harass Jesus, is as calm and peaceful as meditation. You feel as though you’re out of reach of the violence, even as it occurs. It can’t disrupt the contemplative quiet of the painting or the monastery. Although a man spits at Jesus, the spray never reaches him. Jesus sits erect and calm on a throne that looks almost like a stage for a theater piece, further distancing him (and the viewer) from his suffering. At the foot of the platform, St. Dominic thumbs through a book and the Virgin Mary wistfully muses, suggesting that the event is happening in memory rather than the present.

|

Figure 11-2: The floating body parts in The Mocking of Christ make it seem almost like a surreal painting. |

|

Scala / Art Resource, NY

Filippo Lippi: The wayward monk

Although he was a monk, too, Fra Filippo Lippi (c. 1406–1492) was much less devout than Fra Angelico (see the preceding section). Lippi lived a wild life and cavorted with nuns. His masterpiece, Madonna and Child with the Birth of the Virgin (see the color section), though delicate and beautiful, is stuffed with the details of day-to-day life. Instead of transcending the world, like Fra Angelico’s art, Fra Lippi shows the viewer the texture of everyday life: someone running up the steps, tired women carrying baskets to and fro, a child pulling on his mother’s gown.

Whereas Masaccio’s narrative The Tribute Money, combines several instances into rapid succession in one frame, the episodes in Fra Lippi’s painting occur many years apart. Yet these events exist simultaneously on different levels, showing their interconnectedness: Jesus’s birth is possible only because of Mary’s birth, which occurs supernaturally to a barren woman, St. Anne, and is depicted just behind the adult Mary in the foreground. At the top of the stairs, you can see St. Anne nine months prior to the Virgin’s birth, getting the good news. Time moves in a circle in this painting — like a clock, leading the viewer from birth to birth, beginning to beginning.

The color red helps you navigate the painting, leading your eyes around the circle as they leap from Mary’s red garment, to St. Anne’s bedspread, to the drapery above her, to the red shirt of St. Anne’s husband bounding up the stairs. Red also helps to balance this complex composition, as does Lippi’s subtle use of perspective.

The delicacy that Lippi brings to Renaissance painting; Mary’s pale, luminous skin; her transparent veils; and her pretty grace, appear again in the paintings of Lippi’s famous student Botticelli (see the following section) and in the paintings of his son Filippino Lippi (whom Botticelli taught).

Sandro Botticelli: A garden-variety Venus

Sandro Botticelli (c. 1444–1510) is the most poetic painter of the Early Renaissance. His masterpieces, The Birth of Venus and Primavera (see the color section), are painted poems, the visual language of which has intrigued and mystified people for centuries. Both works seem to be painted in a kind of code based on the philosophy of Neo-Platonism. Neo-Platonism (new Platonism) was more than a philosophical fashion in the 15th century. It was the spiritual side of the Renaissance. Its core belief is that man’s origin is divine and his soul is immortal.

Marcilio Ficino, a humble but inspiring genius, who woke with the sun every morning, abstained from sex, practiced vegetarianism, and eventually became a priest, was the father of the Neo-Platonic movement in Florence. He headed an updated Platonic Academy just outside Florence (modeled on the ancient one in Athens). Lorenzo de’ Medici, Leone Battista Alberti, Sandro Botticelli, and Michelangelo all basked in Ficino’s spiritual glow, carrying it into their work. Through Ficino’s correspondence with philosophers, church leaders, statesmen, and kings from Hungary to England, Ficino spread Neo-Platonic ideas and the Renaissance across Europe.

Botticelli’s Primavera (see the color section), which may have been commissioned for a wedding, was supposedly based on Neo-Platonic stories recounted by Lorenzo de’ Medici and turned into a poem by the Renaissance poet Poliziano. In the painting, Venus, the goddess of love, presides over the garden and is the focus of the work. Her son Cupid, flying over her head, aims a fiery arrow at one of the three Graces (the lithe ladies in see-through gowns on the left). Blind as he is, Cupid never misses. Notice how one of the Graces eyes the god Mercury, who’s too busy chasing clouds to notice her. Has she been wounded before Cupid shoots his arrow? Is Botticelli playing Neo-Platonic tricks with time and simultaneous narrative?

On the right, another love story unfolds — not one step at a time, but all at once. Puffy cheeked Zephyr, the sky-colored wind god, thrusts himself into the painting to rape the nymph Chloris. During the encounter, Chloris begins to turn into somebody else: Flora, the goddess of flowers who is standing at her right. The flowers sprouting from her mouth signal the transformation.

After the rape, Chloris/Flora marries Zephyr and scatters flowers about the earth. As the blossoms touch the ground, they instantly take root. Venus’s love garden exists in an eternal springtime, where youth is recycled over and over. Notice that this springtime also enjoys the benefits of fall: blossoming and ripening occur simultaneously. The trees live in two seasons at once, bearing September fruit and April blossoms. Another time trick? Maybe in Venus’s mythical garden love transcends time, and we can experience all seasons at once.

Donatello: Putting statues back on their feet

Donatello (1386–1466) helped birth the Renaissance with his friend Brunelleschi. Like him, Donatello championed a return to classical models in sculpture and architecture. His study of classical sculpture paid off. Acclaimed as the greatest sculptor of the 15th century, Donatello’s achievements in sculpture equaled the Greeks. His bronze David (see Figure 11-3) was the first free-standing, life-size nude in a thousand years. Before David, he’d sculpted superlative three-dimensional niche statues for the walls of Florence’s Orsanmichele that seemed poised to march off their pedestals into the streets of the city.

With David, Donatello took a bolder step and freed his statues completely from the restrictions of the Middle Ages. He literally put statues back on their feet. They were no longer glued and subordinate to architecture (like the jamb statues of Chartres in Chapter 10). Not only did Donatello free statues from their niches, but he broke another taboo by depicting David naked. The statue’s unabashed, sensual nudity would have been X-rated in the Middle Ages.

|

Figure 11-3: The highly polished bronze of Donatello’s David helps to give the statue its sensual appeal. |

|

Gloria Wilder

The bronze warrior helmet of Goliath, under David’s foot, and David’s shepherd’s hat emphasize that a gentle shepherd boy has overcome a brutish, gigantic warrior. David’s flower-wreathed hat is still on his head. Goliath’s helmet and head lie on the ground. A gentle, beautiful boy (a poet and singer) has overpowered a gargantuan bully, yet David doesn’t gloat. He regards the fallen Goliath not triumphantly but wistfully, as if he might shed a tear for him.

With David, Donatello made a political statement, too. Milan was threatening Florence once again. His statue suggests that David-like Florence, a city of refinement, art, and beauty, is mightier than the brutish, Goliath-like dukes of Milan, who were bullying northern Italy.

The High Renaissance

In the Middle Ages, men made things, they didn’t create them. Medieval man believed only God could create. But around 1500, people began to view painters, sculptors, and architects as creators, too. Michelangelo was sometimes called the “divine” during his lifetime, a reflection of society’s changing attitudes. Almost overnight, art makers evolved from artisans into artists, super geniuses who created works of wonder that seemed to rival nature like Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper, Raphael’s The School of Athens, and Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel Ceiling.

It was as if, during the Renaissance, man overcame a 1,000-year-old inferiority complex. In the Middle Ages, people knew their place; they were born into it and couldn’t change it. If your father was a peasant, you were stuck being one, too. All you could do was hope for a better situation in the next life. Aiming too high in this life was a sin. If a medieval artist claimed to create something, he would have been viewed as trespassing on God’s domain.

During the Renaissance, men and women gained a new self-respect and learned to value life on earth as more than a pit stop on the road to the afterlife. Artists began to celebrate not only God, but man.

Armed with supreme self-confidence, Renaissance artists dared to do what men had never before dared. The three super heroes of the High Renaissance (1495–1520) are Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Raphael (now you know where three of the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles got their names — we discuss the namesake of the fourth turtle, Donatello, earlier in this chapter). These High Renaissance geniuses broke through medieval limitations and elevated man with their paintbrushes, pens, and chisels.

In The Creation of Adam Michelangelo painted Adam almost on the same level as God. The creator and his creation practically touch fingertips as the electric charge of life passes from God to man. No medieval artist ever depicted human beings on such a high level.

Similarly, Leonardo elevated man; most famously when he attempted to lift man to the level that earlier generations had assigned to the angels. He gave man wings — or tried to. In 1505, he designed a flying machine, 400 years before the Wright brothers launched their airplane at Kitty Hawk. Despite his ingenious work, Leonardo’s flying machine never got off the page. But his Olympian effort to give man wings was more than High Renaissance ego — it was part of the new vision of man as a co-creator, nearly equal to God.

Raphael elevated man in a quieter way. He brought the Holy Family down to earth, emphasizing Jesus’s humanity even more than his divinity. In his paintings, the Holy Family look like ordinary people. Unlike medieval artists, Raphael, Michelangelo, and Leonardo almost always abandoned the halo (the golden ring that crowns the heads of holy people in medieval art).

Leonardo da Vinci: The original Renaissance man

Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) had a buffet-style brain — every specialty imaginable was on his mental menu. He was the ultimate Renaissance man, not just a super painter and sculptor (though none of his sculptures survive), but an anatomist, biologist, botanist, engineer, inventor, meteorologist, musician, physicist, and writer. He was the almost-discoverer of hundreds of inventions. But because he wrote backwards, no one understood his writings for centuries, and his discoveries went largely unnoticed. (To decode his manuscripts, you need to read them in a mirror and, of course, understand Italian; the man knew how to keep a secret.)

Leonardo’s techniques

The techniques Leonardo employed — including aerial perspective, sfumato, and chiaroscuro — made figures and landscapes appear more realistic. This realism, more than anything else, is what distinguishes Renaissance art from Medieval art (see Chapter 10).

Aerial perspective

Aerial perspective depends on the differences in the thickness of the air. If you want to place a number of buildings behind a wall, some more distant than others, you must suppose that the air between the more distant buildings and the eye is thicker. Seen through such thick air any object will appear bluish. . . . If one building is five times farther back from the wall, it must be five times more blue.

One of the early paintings in which Leonardo used aerial perspective is The Virgin of the Rocks (see the color section). This masterpiece depicts (from right to left) John the Baptist, the Virgin Mary, Jesus, and an angel inside a secluded grotto that opens onto a scene of mystic mountains and a sunken river. You can almost feel the air getting thicker as your eye recedes into the painting.

Sfumato

Sfumato is not dependent on distance like aerial perspective, where far-off mountains appear blue. In fact the “color” of sfumato is more smoky gray than blue. Using sfumato, Leonardo blurred the edges of side-by-side objects just enough so that they seemed part of the same atmosphere.

Chiaroscuro

Leonardo’s greatest works

In the following sections, I take a closer look at two of Leonardo’s most famous paintings: Mona Lisa and The Last Supper.

Behind Lady Lisa’s smile

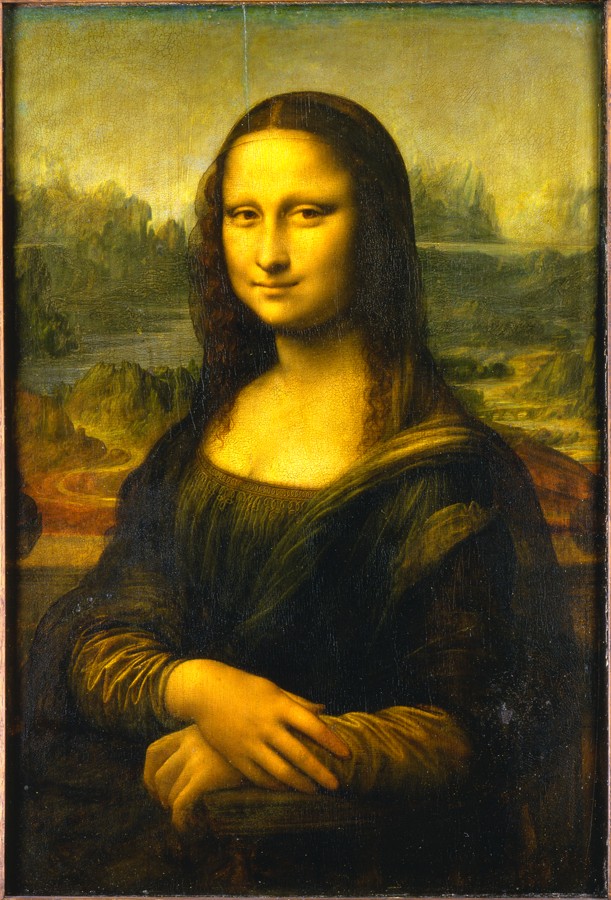

Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa (see Figure 11-4) is the most famous painting in the world. The model for the Mona Lisa was Lisa Gherardini del Giocondo, which is why the painting is also called La Gioconda, which means “the smiling one.”

|

Figure 11-4: Among other things, the Mona Lisa is celebrated for its use of sfumato and aerial perspective. |

|

Réunion des Musées Nationaux / Art Resource, NY

Some say the reason for the Mona Lisa’s celebrity is that her eyes follow the viewer; others think it’s her understated smile that captivates people. I think it’s more than that: Although she was painted 500 years ago, Mona Lisa seems to know her viewers. Her eyes and smile fascinate and disturb because they suggest that she sees through people’s disguises, forcing them to see through their disguises, too. Mona Lisa is a kind of psychological mirror. The longer you gaze, the more you see yourself — through her eyes. She is the perfect icon of the Renaissance: a reflection of man and woman learning to know themselves.

Decoding The Last Supper

Though badly damaged, The Last Supper (see the color section) is still one of the greatest masterpieces in the history of art for many reasons, both historical and technical. For one thing, the painting is a spectrum of human emotions — the first of its kind — captured during an intensely dramatic moment. Previous paintings of the Last Supper focus on the breaking of bread and Jesus saying, “This is my body. Eat this in remembrance of me.” The apostles and Jesus pretty much all share the same somber mood during the ritual. Leonardo chose to focus on a much more dramatic moment: Jesus telling his closest circle of friends that one of them will betray him. This causes an uproar among the apostles, which Leonardo captures, showing each of their reactions. Yet despite the chaos, the painting is orderly and finely balanced, like all great Renaissance art. Jesus’s calm solitude, which contrasts with the animation of the groups of upset apostles, helps to give the painting its sense of order.

Earlier artists isolated Judas by making him sit by himself on one side of the table — as if he were already being punished. Leonardo seats him in High Renaissance fashion — in other words, naturalistically with the others, who are arranged in four groups of three around Jesus. (Three is considered to be a mystical or holy number — for example, the Trinity: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.) The other apostles — except for the one on Jesus’s right — argue about Jesus’s revelation: “One of you will betray me.” The painting’s shadows fall on the guilty one. Judas’s silence and the purse clutched in his hand give him away, too. Again, naturalism rather than the heavy symbolism used by medieval artists broadcasts the message: This guy’s guilty.

Did Leonardo da Vinci code his painting?

Judas and Jesus are not the only silent ones in The Last Supper. The apostle on Jesus’s right is also mute. Usually, this disciple is identified as the young St. John the Evangelist, the guy who wrote the book of Revelation. In his bestseller The Da Vinci Code, Dan Brown identifies this figure as Mary Magdalene. The apostle does look like a woman or an effeminate man. (The youthful St. John is often depicted as a pretty boy in art.)

Many brush off Dan Brown’s interpretation for religious reasons. But Leonardo obviously intended this apostle to stand out from the rest. In other Last Supper paintings, the young John leans against Jesus or sleeps on his shoulder. In Leonardo’s version, the apostle leans away from Jesus and his fate. Also, this apostle is dressed like Christ in reverse. Whereas Jesus wears a blue undergarment and a red robe, this figure wears a red undergarment and a blue robe. And as Dan Brown points out, together the two figures create a V shape, which Brown says is the symbol of femininity (for obvious reasons). As a great artist who used metaphors and double meanings in all his paintings, it’s possible that Leonardo intentionally included this gender bender here: Is the silent apostle a sad, effeminate John or a broken-hearted Mary Magdalene? Or both?

If you compare this figure to other Leonardo women, the face is clearly similar to theirs, especially Mary in The Virgin of the Rocks and The Annunciation. In both Virgin paintings, Mary leans to one side in a gesture of feminine tenderness, as the apostle does in The Last Supper. If you superimpose the silent apostle’s face with that of Mary in The Virgin of the Rocks, the similarity is striking. They have the same feminine roundness in the forehead; the same cheek bones and chin; the same downcast, modest eyes; the same eyebrow line; an identical part in the hair; and the same graceful neck (very unlike the muscular necks of all the other apostles). It’s as if the same model posed for both pictures — a woman. Nevertheless, many Renaissance artists, including Leonardo, sometimes gave young male saints feminine features.

Considering the religious views at the time, including Mary in The Last Supper would have been viewed as heresy. If Leonardo were painting in code, as Brown suggests, he would probably have disguised her, given that, in those days, heretics were cooked on open fires. And who better to hide her behind than the effeminate face of John? The real Mary Magdalene may well have attended the historical Last Supper, so why not suggest her presence? The painting is rich enough to include this possibility. Is the apostle a woman, Jesus’s other half? Mary is probably at least an implied presence in The Last Supper, if not a dinner guest.

Remember: Art is about suggestions, not answers. When you have an answer, if you’re like most people, you tend to stop looking. With great art, you never stop looking.

Michelangelo: The main man

Whereas Leonardo da Vinci created sensitive, intellectual paintings made to be contemplated in drawing rooms, Michelangelo (1475–1564) produced a muscular, heroic art to cover vaulted ceilings, the walls of churches, and large public spaces. His sculptures and paintings seethe with energy and raw emotional power. Even his women are muscle-bound.

Michelangelo’s technique and style

Many of Michelangelo’s statues seem to be in tug-of-war with themselves. Their minds pull one way, their bodies another. Part of this may be due to the fact that Michelangelo was equally inspired by Lorenzo de’ Medici (in whose home he lived during part of his youth and training period) and the fiery evangelist Girolamo Savonarola, whom he befriended as a young man. Michelangelo loved to represent opposite forces in his art: spirit and flesh, night and day, freedom and slavery, peace and violence. In electricity, opposite charges cause current to flow. In Michelangelo’s sculptures, the tension between opposites charges the statues with spiritual force.

Michelangelo’s greatest works

In the following sections, I cover three of Michelangelo’s most celebrated works: the Pieta, David, and the Sistine Chapel Ceiling.

The Pietà

Michelangelo used tension in his early masterpiece the Pietà, begun when he was just 23 years old. In the Pietà, the dead Christ’s muscles still show the strain from his recent agony on the cross, yet his face radiates perfect peace and glows with an otherworldly light. Michelangelo polished Christ’s marble features so that they would reflect light as if it were radiating from within, suggesting Christ’s transcendence of death. The relationship between Mary and Jesus in the Pietà also brims with tension. Mary cradles the dead Christ as she once cradled the infant Jesus. Her womb has become a tomb; death and life merge in her arms. Michelangelo’s Pietà is a marriage of earthly suffering and heavenly beauty, the contrast between them making each spiritual state more intense, more electrifying.

David

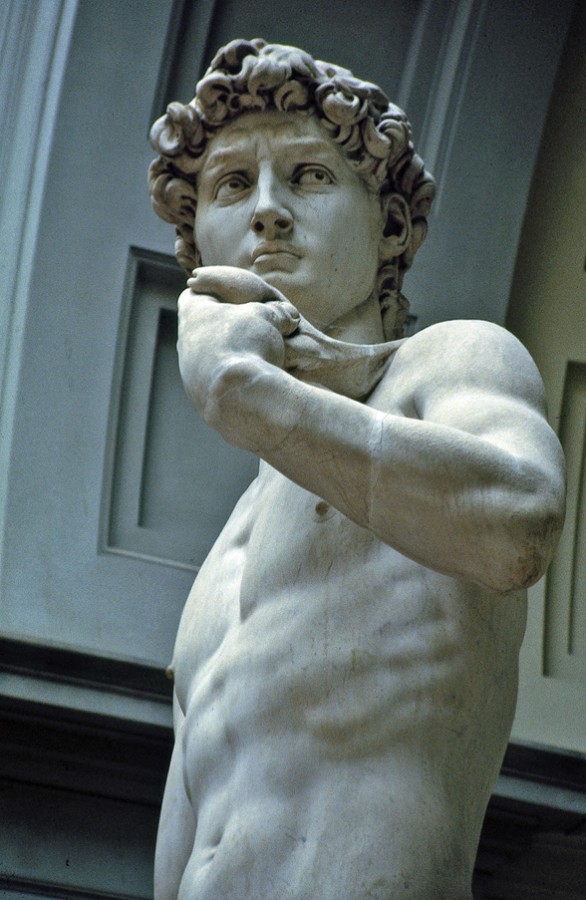

The tension in Michelangelo’s David (see Figure 11-5) is just as potent as in the Pieta (see the preceding section). David appears calm and confident, yet tense and poised for action like a taut bow. You can see the approaching battle in his eyes. He has the grace and physical harmony of a classical Greek statue (see Doryphoros in Chapter 7), but the emotional intensity and titanic self-confidence of a Renaissance man.

From a historical perspective, David was meant to be a symbol of Florence, small but tough. He was a warning to any wannabe Goliaths (like Rome or Milan) who might try to conquer Florence.

|

Figure 11-5: In Michel-angelo’s version of the biblical story of David and Goliath, you see only the young challenger David. But you can sense Goliath’s presence in David’s focused and fearless eyes. |

|

Gloria Wilder

Sistine Chapel Ceiling

Painting the Sistine Chapel Ceiling was a four-year backache Michelangelo didn’t want. But there was no arguing with Julius II, the impatient pope who commissioned the work. In a poem written at the time, Michelangelo complained about his job: “My loins have moved into my guts/As counterweight, I stick my bum out like a horse’s rump . . . I bend backward like a Syrian bow. . . .” Michelangelo’s grand struggle to paint a 68-foot-high ceiling the size of a basketball court is the most famous example in the history of art of an artist suffering for his work.

The ceiling recounts Genesis and other Old Testament stories. The visual narrative begins with God separating light from darkness above the altar and ends with the story of Noah’s drunkenness over the entrance. The creation of Eve is told in the middle of the ceiling.

In the most famous panel, The Creation of Adam (see Figure 11-6), Michelangelo captures the first moment of human consciousness with his brush. Adam has an adult body, but his face is filled with childlike wonder as he looks at God out of newly created eyes. His body and pose also suggest the innocence of this brand-new being. Adam looks freshly minted, as peaceful and content as a newborn when he first meets his mother’s eyes. In typical Renaissance fashion, the emphasis here is on man, on Adam’s reaction to being created, more than on God — even in this traditional Bible story.

|

Figure 11-6: Notice that in The Creation of Adam, man is physically almost on the same level as God. |

|

Erich Lessing / Art Resource, NY

Raphael: The prince of painters

High Renaissance art is often known for its grace, balance, and harmony. No painter better depicted these qualities than Raphael (1483–1520). Unfortunately, after a stunning outpouring of masterpieces, he died at 37.

You can think of Raphael as the spiritual son of both Leonardo and Michelangelo. He learned from both of them, and then created his own style. He borrowed tenderness from Leonardo’s paintings and muscular energy from Michelangelo. In Raphael’s years in Florence, he painted the most motherly Madonnas of all time. Many of them appear on holiday postage stamps and Christmas cards today. Raphael’s angels are popular, too — they’re practically Valentine’s Day icons. His Madonna and Child paintings are often based on the pyramid and include John the Baptist. They’re always perfectly balanced, to illustrate ideal Renaissance order and perfect human harmony in relationships (the kind of relationships we all wish we had!), as you can see in his Madonna with the Goldfinch (see the appendix).

Raphael’s techniques

Raphael is known as the painter’s painter. He was the ideal to which other painters aspired for nearly 400 years.

What’s so special about Raphael? For one thing, he built his paintings on geometrical grids, so the proportions and spacing between figures would appear as formal and perfect as a cube or triangle. For example, he often built his Holy Family paintings on a pyramid structure. Yet his paintings don’t look like a math problem — they seem completely natural.

Raphael united the perfect harmony of classical art (in which proportions are as balanced as a set of scales in equilibrium — see Chapter 7) with naturalism and idealism. By idealism, I mean that his paintings transport you to a place of perfect peace and beauty.

Raphael’s greatest work

Raphael’s greatest masterpiece is The School of Athens (see Figure 11-7), a fresco in the Stanza della Segnatura of the Vatican. The walls of the Stanza weren’t blank when Pope Julius II ordered Raphael to paint them — they were decorated with frescoes by other great artists, including Raphael’s teacher Pietro Perugino and his friend Il Sodoma. The pope commanded Raphael to cover their work with plaster and then paint over it.

The School of Athens is really two schools: the old school of Athens and the new school of Florence. Many old-school characters — including Plato, Euclid, and Heraclitus — are represented by new-school artists. Plato has the face of the aging Leonardo da Vinci. Donato Bramante, the architect who got Raphael his job at the Vatican, represents Euclid studying a diagram.

|

Figure 11-7: Notice how Raphael divided The School of Athens into two balanced halves. |

|

Scala / Art Resource, NY

Raphael’s point was to suggest that Florence is the home of the rebirth of Greek culture and learning. Seventy years earlier, Cosimo de’ Medici had gathered Florentine thinkers and artists into an academy in Florence based on Plato’s ancient school.

But if that’s the case, where’s Michelangelo? Raphael stuck him in later, either as an afterthought or because he had sneaked a peak at the antisocial master while he was frescoing the Sistine Chapel Ceiling next door. Raphael made Michelangelo the hermit-like Heraclitus in the foreground, the Greek philosopher who loved contradictions.

Raphael even included himself in the lower-right corner of the painting as a student. Note that Raphael is the only one in The School of Athens who is aware of the world outside the school (beyond the fresco). He looks directly at the viewer, perhaps to invite the viewer in. To make amends for covering up his art with plaster, Raphael placed his friend Il Sodoma beside him as a fellow student in the elite School of Athens.

The School of Athens is a masterpiece of perspective, composition, and balance. The spatial balance, which is easy to see, suggests other kinds of balance. Raphael divided the painting into two halves: The Platonic idealists are on the left; the Aristotelian realists are on the right. Plato (left) and Aristotle (right) stand side by side at the focal point under the last arch. Plato, the idealist, points skyward; Aristotle, the realist, points straight ahead and down at the physical world. Raphael put these two opposing schools of philosophy under one roof so that they could balance each other. In front of the dueling philosophers, Heraclitus (Michelangelo) ponders the union of opposites.

Western philosophy and science aren’t the entire curriculum in The School of Athens. A dose of Eastern philosophy, represented by the great Persian mystic Zoroaster (a contemporary of Heraclitus) and the 12th-century Arab wunderkind Averroes, brings additional balance to the school. (Averroes’s translations of Aristotle helped revive Aristotelian philosophy in the West.)

The arches within arches that frame the school don’t shut it off from the rest of the world. Instead, they open it up, allowing knowledge to breathe and expand into the universe beyond the school’s walls.