Chapter 16

All Roads Lead Back to Rome and Greece: Neoclassical Art

In This Chapter

Seeing how the Enlightenment affected art

Seeing how the Enlightenment affected art

Connecting painting and politics

Connecting painting and politics

Reading between the brushstrokes

Reading between the brushstrokes

The 18th-century Enlightenment philosophers thought they’d found the light that went out when ancient Rome fell. Reason, not faith, was their torch. It would illuminate man’s path to political and social reform, reveal nature’s secrets, and elucidate God’s plan — if he has one. Enlightenment thinkers advocated natural science and natural religion, all subject to rea-sonable laws that can be deduced using rational inquiry and the scientific method pioneered by Galileo and René Descartes in the 17th century.

Enlightenment philosophers viewed with horror the faith-driven wars of the Reformation (in the 16th and 17th centuries), which devastated Europe. They witnessed irrational emotionalism and prejudice in their own day that led to religious intolerance, poverty, injustice, and censorship of new ideas in most countries and households. It was time for the pendulum to swing from the heart to the head, from faith to reason.

The German Enlightenment philosopher Immanuel Kant said:

Enlightenment is man’s emergence from his self-imposed immaturity. Immaturity is the inability to use one’s understanding without guidance from another. This immaturity is self-imposed when it comes not from lack of understanding, but from lack of determination and courage to use [one’s intelligence] without outside guidance. Sapere Aude! [Dare to know!] — that is the motto of the Enlightenment.

One hundred and fifty years earlier Galileo Galilei said practically the same thing:

I do not feel obliged to believe that the same God who endowed us with sense, reason, and intellect intended us to forgo their use. . . .

The Holy Inquisition put Galileo under house arrest for the last nine years of his life for using his reason to contradict the Church’s faith-driven geocentric view of the universe (“geocentric” means the sun, planets, moon, and stars revolve around the Earth). Enlightenment thinkers were an optimistic bunch. Despite what happened to Galileo and the fact that many of them were censored, exiled, and imprisoned, most were convinced that man could solve his own problems through calm reason. Today when you tell someone “Calm down and think” or “Look before you leap,” you’re subscribing to an Enlightenment attitude — whether you realize it or not. Among the greatest and most influential Enlightenment thinkers were John Locke, Voltaire, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Denis Diderot, Montesquieu, Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Paine, Mary Wollstonecraft, Immanuel Kant, and David Hume. Many of these figures were influenced by the great 17th-century rationalists René Descartes and Sir Isaac Newton.

Voltaire preached freedom of religion and separation of church and state, the right to a fair trial, and civil liberties. John Locke said a “government is legitimate only if it has the consent of the governed” and only if it guarantees the “natural liberties of life, liberty, and estate.” Montesquieu advocated separation of powers into three independent but interlinked branches of government. These and other Enlightenment thinkers inspired the American and French Revolutions, the U.S. Bill of Rights, and the French Rights of Man, as well as the U.S. and French constitutions. They inspired democratic and independence movements from Venezuela to Greece, and they turned on “Enlightened monarchs” like Catherine the Great and Holy Roman Emperor Joseph II, who instituted humanistic reforms like abolishing serfdom and building public schools (enlightenment for everybody).

Rousseau called for didactic art (art that teaches enlightened ideals) and a return to high-minded classicism (beautiful, idealized art that elevates people). He condemned what he considered the frivolous art of the Rococo, especially the playfully erotic paintings of François Boucher.

Enlightenment ideals birthed the Neoclassical art style, which was originally called the “true style,” to contrast it with the artificiality of Rococo art, which was fashionable until around 1760 (see Chapter 15).

Johann Joachim Winckelmann, the German art historian and founder of the Greek Revival in art, said the “true style” should have a “noble simplicity and calm grandeur.” Although he wanted to revive Greek art, he rejected carbon copies of it. Instead, he encouraged a recharging of the ancient spirit. He believed this would produce an updated version of Greek art, a marriage of the classical style with Enlightenment thinking — Neoclassicism.

In this chapter, we examine 18th-century art that reflected Enlightenment ideals.

Jacques-Louis David: The King of Neoclassicism

Jacques-Louis David (1748–1825), the greatest Neoclassical painter, was highly influenced by Winckelmann. David’s first masterpiece, The Oath of the Horatii, exemplified the “noble simplicity and calm grandeur” that Winckelmann advocated.

Grand, formal, and retro

Louis XVI (whose death warrant Jacques-Louis David would later sign during the Revolution) gave David his first big job as a painter. Actually, the king’s director of arts and buildings, Count d’Angivillier, presented David the commission on the king’s authority. Count d’Angivillier decided that France needed historical paintings with high-minded themes that would inspire patriotism. (The tremors of the coming revolution could already be felt.) The count hired David to paint a historical canvas (the artist got to choose the subject) that would promote unwavering patriotism as the threat of revolution loomed.

David chose to illustrate a fanciful story about an ancient war between Rome and a rival city-state, Alba. Instead of clashing armies, the “war” was simply a showdown between two groups of brothers: the three Horatii boys, who lived in Rome, and their Curiatii cousins who resided in Alba — kind of like an early version of a mob war. He called the painting The Oath of the Horatii. In the painting, the father of the Horatii brothers hands them their swords. The weeping women on the right have ties to both bands of young men — the ones we see and the off-canvas Curiatii. One of the women is a Horatii who’s engaged to a Curiatii. Another is a Curiatii who’s married to a Horatii. It’s like two Romeo and Juliet stories rolled into one — complete with rhymes! But the moral isn’t that love conquers all; it’s that patriotism overrides love.

The Oath of the Horatii expresses a rational, geometric sense of order and total commitment to the state, without messy emotion to distort the classical proportions of the figures or the background.

The three classical arches resting on Greek Doric columns frame the action. Nothing spills over the edges of this perfectly composed painting. That would be emotional, sloppy, and anticlassical. David does include some sentiment, but it’s reserved feeling — a classical grief, so softened and restrained that it doesn’t distort the women’s beauty.

In fact, the men appear to have no feelings other than patriotism, while the women look as though they’re on sedatives.

Propagandist for all sides

During the French Revolution, David quit painting what amounted to propaganda pictures for King Louis XVI and joined the radical Jacobins who overthrew the king. David idolized the Jacobin leader Maximilien Robespierre, the architect of the Reign of Terror. David also signed the king’s death warrant in 1792 with most of the Jacobins.

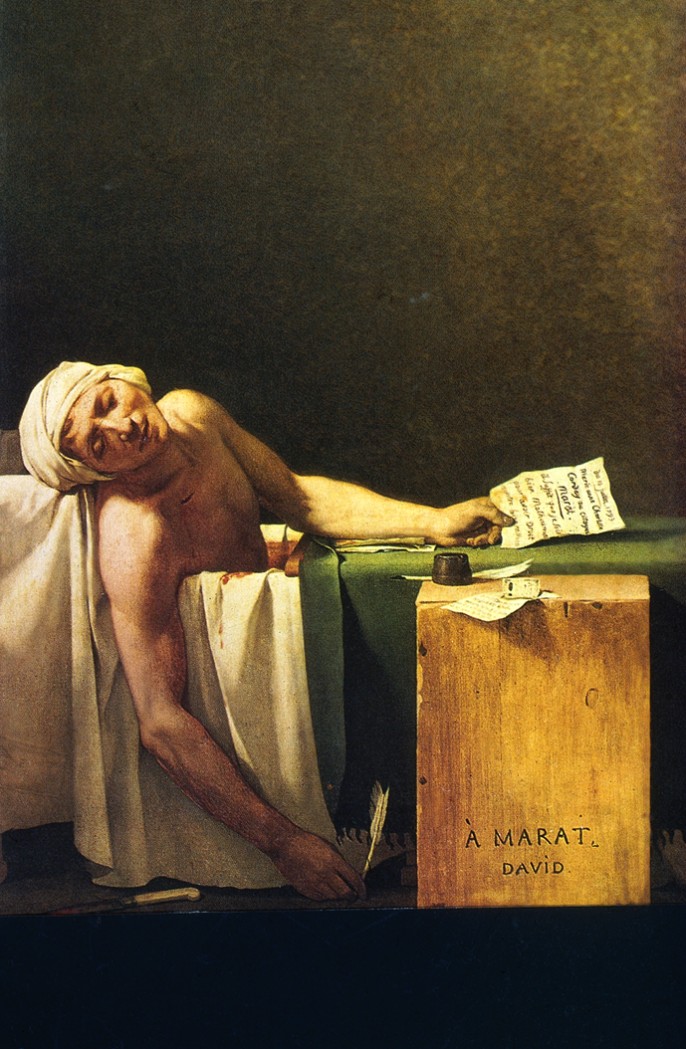

One of David’s most famous paintings is of his friend and fellow Jacobin, Jean-Paul Marat, who was murdered in his bathtub by the political moderate Charlotte Corday (see Figure 16-1). Corday connived her way into Marat’s bathroom by posing as an informant. She claimed that she had a list of lukewarm revolutionaries (moderates like herself), the kind of people Marat routinely carted off to the guillotine. As he scribbled down the names, she pulled out a knife and stabbed him. In David’s painting, Marat still holds Corday’s letter is his left hand; he grips the pen in his right. The bloody knife lies inches from his body, a more potent weapon than Marat’s “bloody” pen, which had sent so many to the guillotine.

The bold inscriptions on the painting read “A Marat [to Marat], David,” suggesting that the painting was a tribute to his friend. But the inscription was written as one might sign a letter, so the letter motif comes ’round full circle: Corday delivered a letter (her name is written on it), Marat began copying it and was stabbed, and David turned the whole painting into a farewell letter to his friend.

|

Figure 16-1: David’s The Death of Marat, painted in 1793, is both a memo- rial to a friend and propaganda. |

|

Gloria Wilder

The light falling on Marat through the window behind him makes him seem divine, like a martyred saint. He was called one of the three gods of the French Revolution. When Robespierre unleashed the revolution’s iconoclastic phase against the Catholic churches, Marat’s bust was often put in place of images of Christ.

After Robespierre’s fall and execution, David was imprisoned briefly. But he survived to change sides again. The former radical Republican became an avid Napoleon Bonaparte supporter, even after Bonaparte crowned himself emperor. David seemed to gravitate to wherever the power was. He once raved that Napoleon Bonaparte “is a man to whom altars would have been raised in ancient times.”

Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres: The Prince of Neoclassical Portraiture

Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres (1780–1867) was David’s greatest student. He tried to follow in his teacher’s footsteps as a history painter but couldn’t cut it. He excelled at intimate, sensual close-up paintings, not sweeping documentary scenes. Ingres was a brilliant, sensitive portraitist, although his greatest works are usually considered to be his female nudes in exotic settings.

When he first exhibited The Great Odalisque (which means “female harem slave”; see the color section) in 1819, critics and the public verbally attacked it. But after the initial shock, the painting grew on them. Ten years later, it was a triumph. But in the meantime, Ingres left France to study and paint in Rome, where he did portraits for a living. Business was so good that he refused to paint anyone he didn’t like. Later, he moved to Florence, where he received few commissions and lived on the edge of poverty with his wife. Returning to France in 1826, Ingres discovered he was famous.

Although the painting is a Neoclassical masterpiece, The Great Odalisque isn’t an example of classical perfection. She has mannerist proportions: Her hips are too large; her neck and shoulder line, too long. Her proportions were among the things viewers initially criticized. But the exaggeration is intentional; it makes The Great Odalisque seem even more luxurious and languorous. The figure’s nearly classical beauty is mixed with a cool, listless sensuality that classical art never had and marks this painting as Neoclassical.

Ingres puts The Great Odalisque on display, invites the viewer’s eyes to wander over her flesh. Yet her own eyes keep the viewer at a distance. She is a voyeur, too — watching not the viewer, but her master.

The soft pillows and crumpled sheet on the couch are an invitation to pleasure, yet the slave resists in a soft-spoken way. She modestly covers her bare calf with the drape, as if she would like to cover more. She turns her body away from, and her face toward, her master. The cool blue colors of the drapes and couch, which contrast sharply with her ivory skin, emphasize her lackadaisical sexuality.

Élisabeth-Louise Vigée-Le Brun: Nice and Natural

Instead of participating in or being inspired by the French Revolution, Élisabeth-Louise Vigée-Le Brun (1755–1842) fled from it. She was an exceptionally talented painter, one of the few women accepted in the French Royal Academy and the personal portraitist of Marie Antoinette, whom she painted about 30 times.

Female artists were expected to paint only women, children, and flowers. Most of Vigée-Le Brun’s paintings were of women, though she also did about 200 landscapes. But her portraits are not merely pretty — they capture the characters of her sitters. Her self-portrait with her young daughter shows the tender, close relationship between mother and child, while revealing aspects of each of their characters (see Figure 16-2). The little girl, Julie, is shy, yet innocently intrigued by what she doesn’t understand. Vigée-Le Brun’s expression is more complex. She didn’t like being pregnant because it interrupted her painting. Even on the last day of her pregnancy, she’d hurry back to her canvas and continue working between contractions, which she found “irritating.” She seems to recall this in the portrait and appears surprised by the delight that motherhood now gives her, despite the interruptions. The Madonna-and-child pose adds another level of charm, especially because this child is a girl.

|

Figure 16-2: Vigée-Le Brun’s self-portrait with her daughter captures the sweet charm of an adoring mother and her daughter. |

|

Réunion des Musées Nationaux / Art Resource, NY

The most remarkable thing about [the queen’s] face was the splendor of her complexion. I never have seen one so brilliant, and brilliant is the word, for her skin was so transparent that it bore no umber in the painting. Neither could I render the real effect of it as I wished. I had no colors to paint such freshness, such delicate tints, which were hers alone, and which I had never seen in any other woman.

The last painting Marie Antoinette commissioned from Vigée-Le Brun was of her surrounded by her four children. When Louis XVI saw it, he told the artist, “I know nothing about painting, but you make me like it.” The French Revolution erupted a year later.

Canova and Houdon: Greek Grace and Neoclassical Sculpture

In many cases, Neoclassical statues look a lot more Greek than Neoclassical paintings. Many of them, especially Canova’s, have classical composure, proportions, and grace. And yet Neoclassical statues look newly minted, even today.

Antonio Canova: Ace 18th-century sculptor

Antonio Canova (1757–1822) was the greatest Neoclassical sculptor and the greatest sculptor of the 18th century. Although he was born in Venice, he developed his style in Rome, by studying and copying Ancient Roman statues and reliefs. He also came under the influence of Johann Joachim Winckelmann in Rome (see the introduction to this chapter).

Canova’s Roman copies were so impressive that Roman city officials offered him a long-term, well-paid job making copies. Even though he was only 20, Canova refused, saying if he always made copies, he would never learn to become a great artist in his own right.

Instead, he absorbed and then expanded the Ancient Greek style. For example, Canova gave the bodies of Cupid and Psyche perfect classical proportions. But their tender, passionate gestures would be out of place on the Parthenon or in a Roman temple. Romans and Greeks kept that emotional display behind closed doors; showing too much feeling was a sign of weakness or craziness.

Jean-Antoine Houdon: In living stone

Jean-Antoine Houdon (1741–1828), like Canova, was inspired by Winckelmann and made a trip to Italy to study ancient sculpture. He specialized in sculptural portraits, which have never been surpassed. His statues are so realistic that they look like they might start delivering speeches or writing new laws. He combined a sharply observed realism with an elevated, Neoclassical restraint. He made busts of many heroes of the Enlightenment, including Voltaire, Rousseau, Diderot, the Marquis de Lafayette, Benjamin Franklin, George Washington, and Thomas Jefferson. The sculptures preserve not only their features but also their personalities for posterity.

Sometimes Houdon dressed his figures like Roman senators or consuls. He draped Voltaire, who posed for him just a few weeks before his death in 1781, in a toga. Houdon dropped the classical attire for his statue of Washington and his bust of Jefferson, which he sculpted a little later — Washington between 1785 and 1788 and Jefferson in 1789. Both Americans wear elegant period clothing — the Armani suits of the day. Their poses are presidential and enlightened.

Realism mattered so much to Houdon that he hopped on a boat for the United States to do in-person studies of Washington and Jefferson. Similarly, when he heard that Rousseau had died, he rushed to his wake and made a cast of the dead man’s face. Shortly after, he sculpted a lifelike bust of Rousseau from the cast.