Chapter 21

From Fauvism to Expressionism

In This Chapter

Seeing how the Post-Impressionists influenced the next generation of artists

Seeing how the Post-Impressionists influenced the next generation of artists

Understanding flattening perspective

Understanding flattening perspective

Decoding color theory

Decoding color theory

Straightening out distortion

Straightening out distortion

Fauvism and Expressionism — the first art movements of the 20th century — set the tone for modern art. Both groups inherited many characteristics from the Post-Impressionists, especially Paul Gauguin, Vincent van Gogh, and Paul Cézanne. Between 1901 and 1906, the Post-Impressionists enjoyed a surge in popularity. Major exhibitions of their paintings opened in France and Germany, introducing the new generation of artists to their work. In many ways, the Fauves and Expressionists picked up where the Post-Impressionists left off.

What was it about van Gogh, Gauguin, and Cézanne that turned on the Fauves and Expressionists? Van Gogh’s expressive use of color and line (each of his brushstrokes sings or shouts) and Gauguin’s clashing color patches and flattening of space appealed to both groups. Cézanne’s method of reducing nature into its geometric components (cylinder, cone, and cube) was also highly influential. Beyond their innovative techniques, all three artists expressed their own feelings on canvas instead of painting traditional historical and religious art for public spaces. Similarly, the Expressionists and Fauves believed that they should express their personal visions in their art rather than cater to public taste.

Besides Gauguin, van Gogh, and Cézanne, the German Expressionists were strongly influenced by Norwegian Symbolist painter Edvard Munch (who painted The Scream) and the Belgian James Ensor (see Chapter 20).

In this chapter, I examine the work of the leading Fauves — Henri Matisse, André Derain, and Maurice de Vlaminck. Then I delve into Expressionism, exploring the Die Brücke and Der Blaue Reiter movements in Germany, and Austrian Expressionism.

Fauvism: Colors Fighting like Animals

The critic obviously preferred the traditional bust to the garishly colored canvases. But the artists liked his insult and adopted the name. To them, being called “wild beasts” was a compliment. Their colors were meant to attack, to assault the eye. So what if conservative critics fled from their colors? The critics had condemned van Gogh and Gauguin at first, too. As the Expressionist painter Franz Marc wrote, “New ideas are hard to understand only because they are unfamiliar. How often must this sentence be repeated before even one in a hundred will draw the most obvious conclusions from it?”

The Fauves didn’t have a political or social agenda — which may be why the movement only lasted three years — but they shared similar views about technique and the importance of individual expression. All of them used loud colors and flat surfaces; all of them were young talented painters who wanted to experiment. Eventually, the Fauves’ work won acceptance. In fact, most of the Fauves became famous in their lifetimes.

In 1906, two more artists, Raoul Dufy and Georges Braque, joined their group. Braque became one of the founders of Cubism (see Chapter 22) just a few years later.

Henri Matisse

Henri Matisse (1869–1954), the leader of the Fauves, adopted Gauguin’s flat surfaces, use of visual symbols, and clashing colors. But he didn’t use a garish palette to probe the primitive and instinctual side of man as Gauguin did. He preferred playful, happy hues. “What I dream of,” he wrote, “is an art . . . devoid of troubling or depressing subject matter . . . [art that is like] a good armchair in which to rest.”

Matisse’s early masterpiece The Joy of Life (see the color section) is just such an armchair. Instead of attacking, these colors want to play. In the painting, Matisse spreads an imaginary pastoral landscape before the viewer. Blithe nudes lounge about, dancing, playing instruments, picking flowers, and making love. It could almost be a Rococo pleasure garden painted by Boucher (see Chapter 15). But the bodies aren’t pink and fleshy like Boucher’s. Instead, they’re stylized, rendered with a few fluid lines. Also, instead of using traditional perspective like the Rococo painter, Matisse’s paradise is as flat as wallpaper — well, almost. There’s a hint of depth: The background dancers are smaller than the foreground lay-abouts.

The nudes have almost no modeling (degrees of light and shade that give a three-dimensional look). They’re just pink or pale blue, two-dimensional figures. And these aren’t the only novelties. Matisse’s islands of color were revolutionary. True, Gauguin used color patches to suggest primeval emotion and psychological states. But Matisse’s colors are more than mood indicators. They’re geographical locations, places to hang out. The background women dance on a color (bright yellow) rather than a field; lovers walk through colors (red and yellow) instead of groves or parks. Also, the colors are alternately hot and cool, harmonious and discordant, which keeps your eyes moving quickly over the canvas — as if you were being playfully chased by “wild beasts.” This enhances the joy-of-life feel of the painting.

Like Gauguin, Matisse placed his figures in nature where they could act out their passions without inhibitions. But these are bright passions, not dark ones like in Gauguin’s Savage Tales. Instead of probing man’s primordial nature, Matisse’s colors dance on the surface of life. The painting is what its title says it is, The Joy of Life. Who needs anything more?

Matisse simplified even more than Gauguin. One curving line of blue-green paint signifies a tree trunk (though some look like wavering kite strings). One sweeping line suggests a hip, thigh, or arm, as well as the emotions that determine the posture. He said, “Drawing is like making an expressive gesture with the advantage of permanence.”

Matisse’s command of anatomy enabled him to reduce shapes to their most basic contours. But The Joy of Life is more than an exercise in reduction. Matisse discovered how to transcribe human emotion with a single line or series of lines. Together, the flowing lines of bodies and trees create a current of happiness that streams through the painting. The scene implies that life doesn’t have to be complex. It can be reduced to fundamental lines, uncomplicated colors, and simple pleasures.

Instead of using color to mirror real life, Matisse laid down colors musically, creating visual harmonies. He wrote, “I cannot copy nature in a servile way, I must interpret nature and submit it to the spirit of the picture — when I have found the relationship of all the tones the result must be a living harmony of tones, a harmony not unlike that of a musical composition.”

André Derain

André Derain (1880–1954) and Matisse founded Fauvism in 1905 while painting together in the seaside town of Collioure in southwestern France. Derain’s painting Mountains at Collioure is one of his best works from that trip. No visual landmarks in the painting identify the place (which became a hangout for the Fauves and other artists, including Picasso). In fact, the landscape looks Provençal, probably because van Gogh and Cézanne, both of whom painted in Provence, inspired Derain. Derain’s slab-dab, van Gogh–like brushstrokes — which look like streaks of energy spraying through the canvas — make the landscape look like it’s charged with electricity. Like van Gogh’s countrysides, the undulating fields and mountains seem to breathe. The geometric shapes with which he composes the mountains show the Cézanne influence. But the shrill, complementary colors and flatness are pure Fauve.

At a glance, the painting does look like something a creative 10-year-old might bring home from school. But that’s not a bad thing; it gives the painting its freshness. Like Matisse, Derain arranges his colors and lines to create harmonies and discords. The mountains and trees are painted with fighting, complementary colors (the mountains with oranges and blues, and the trees with oranges and greens). But he also combines friendly, analogous colors — greens and yellows — to give the viewer’s eyes a pleasant break from the stress of the harsh hues.

Maurice de Vlaminck

Maurice de Vlaminck (1876–1958), along with Matisse and Derain, was one of the original Fauves. He was also a talented violinist, cycling pro, and writer. Vlaminck’s favorite model was France itself — its landscapes and small towns; the sites a cyclist might encounter on an outing. Like Matisse, Vlaminck arranged colors musically. In Flowers (Symphony of Colors), he masses colors with crescendos of intensity, while juxtaposing fighting colors to create the Fauve look: a blue notch in an orange tree, green shutters on a bright red house.

Vlaminck was highly influenced by van Gogh. Like van Gogh, Vlaminck laid on the paint thickly — so thickly that sometimes it looks like icing on a cake. To intensify his colors, he squeezed paint directly from the tube onto his canvases.

Vlaminck never flattened scenes like Matisse, but he used traditional per- spective. Also, he never gave the viewer close-ups of houses and buildings. Instead, he showed the viewer the towns from a cyclist’s point of view, as if the towns have just come into sight as you peddle around a bend on the Tour de France. Ironically, the houses, trees, and streets in Vlaminck’s paintings abound with exuberant life and mystery, but the streets are always empty. The life force in his paintings comes from the architecture, not the inhabitants.

Vlaminck’s style changed dramatically after he saw a Cézanne exhibit in 1907. His Landscape Near Martigues, for example, which is composed of geometrical blocks of pale color, looks as though Cézanne could have painted it.

Friendly versus fighting colors

Think of colors that live next door to each other on the color wheel — yellows and oranges, greens and blues, and so on — as friendly or neighborly colors. They get along because they have something in common. Green is made of yellow and blue; therefore, it blends harmoniously with both of them. Technically, these are called analogous colors, because they have something in common. (Analogy means “correspondence between dissimilar things.”)

Fighting colors live on opposite sides of the color wheel and have nothing in common. There’s no red in green, no yellow in purple. When you juxtapose these colors, they clash, each bringing out the other’s personality. The sense of being the other’s opposite, or complement, is why they are referred to as complementary colors.

German Expressionism: Form Based on Feeling

Expressionism sprang up in Germany at the same time the Fauves staged their first exhibition in France. Technically, the two movements have a lot in common: Expression dominates form; perspective is often flattened; and both use in-your-face, garish colors. But whereas the Fauves were a lighthearted bunch, the German Expressionists had a penchant for brooding.

There are two German Expressionist groups, Die Brücke (The Bridge) and Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider). Die Brücke was the gloomier of the two.

Die Brücke and World War I

In 1905, tensions that had been building for centuries in Europe were on the verge of rupturing. A worldwide conflict seemed inevitable to many people. The 1905 war between Japan and Russia was viewed by many as a tremor before an earthquake. The old order was cracking at the seams. Avant-garde artists wanted it to crack. Many hoped for a complete collapse so they could rebuild society on the ruins of the past. When war came in 1914, many of the German Expressionists, led by visions of reforming the world, enlisted. Some never returned or, if they did, they came back mad. But I’m jumping ahead of myself.

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Erich Heckel, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, Fritz Bleyl, and other like-minded artists founded Die Brücke in 1905 in Dresden. Kirchner, the leader of the movement, wrote in a 1906 woodcut (a favored media of Die Brücke, because it was cheap and quick):

We believe in development and in a generation of people who are both creative and appreciative; we call together all young people, and — as young people who bear the future — we want to acquire freedom for our hands and lives, against the well-established older forces. Everyone belongs to us who renders in an immediate and unfalsified way everything that compels him to be creative.

Like Gauguin, their revolt was a return to primitivism. This is one reason they liked to paint nudes: Nudes have been stripped of social conventions.

Like the Impressionists, Die Brücke artists painted from life, en plein air. Therefore, they had to be fast. But to express their heavier, darker feelings, they slapped more paint on the canvas than the light-as-air Impressionists, which slowed them until they learned to thin out the paint by mixing in petroleum. Like the Fauves, Die Brücke artists preferred to use clashing, complementary colors. They especially felt a kinship with Gauguin, whose paintings probed the underbelly of life. To express man’s instinctual side was viewed as spiritually purifying — no matter how impure the art might look to others. The Expressionists were proud that they faced the dark side of human nature in their art, instead of shoving it under the carpet.

The members of Die Brücke drew and painted together, developing a common style and a shared visual vocabulary. Their focus was the human form, which they regarded as the ultimate vehicle for expression. A twisted expression on someone’s face, a contorted posture, became the language with which they communicated their own feelings. Like Gauguin, they used unnatural colors to convey inner tensions.

For Die Brücke artists, the old forms of art weren’t suitable vehicles. They refused to paint pretty portraits or lush landscapes. Their own feelings were the subjects of their art. Kirchner wrote, “He who renders his inner convictions as he knows he must, and does so with spontaneity and sincerity, is one of us.” Van Gogh’s tumultuous landscapes, deranged architecture, and explosive colors inspired them because his emotions live on inside his paintings. They, too, wanted to express their feelings so strongly that the landscapes or cityscapes in their paintings were reshaped by them. Buildings grimace and slouch according to the painter’s mood. Arms and faces are contorted to express the artist’s angst.

Think of classical art as a beautiful gilded box. Die Brücke Expressionists didn’t want to eliminate the box (though they could do without the gilding). They wanted to bend it and bash it in so the box revealed the emotional battles raging inside of it. The perfect exterior of the classical box (a Gainsborough portrait of a composed aristocrat, for example, who never cries too hard or smiles too much) hid the interior warfare that goes on in every individual.

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner

In 1911, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner (1880–1938) moved to Berlin. The other members filtered into the German capital over the next couple years. Many of Kirchner’s greatest paintings are portraits of seamy Berlin street life. In these works, you feel as though you’re viewing life through a fisheye lens or in a hall of mirrors. The men, dressed exactly the same, seem like clones of each other, which contributes to the hall-of-mirrors impression. Kirchner usually separates the sexes — boys on the right, girls on the left — which intensifies the sexual charge coursing between them.

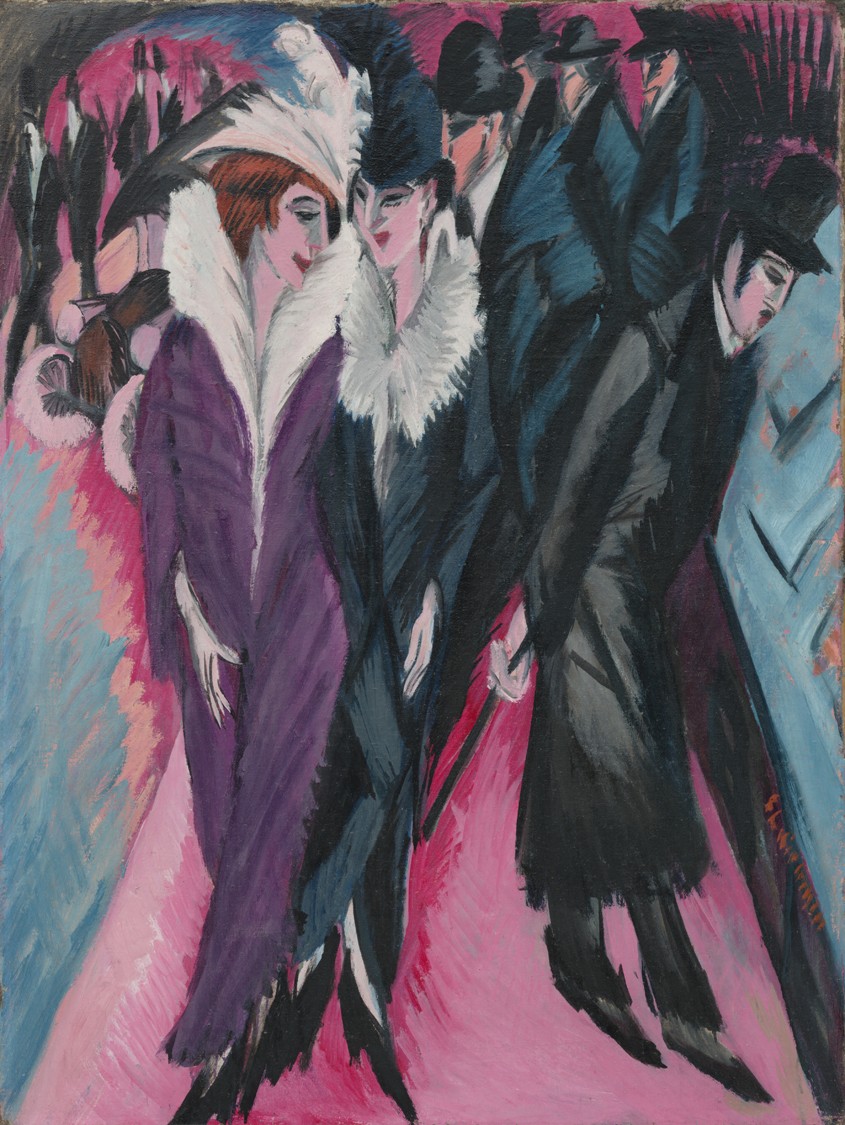

In Street, Berlin (see Figure 21-1), Kirchner’s color palette is like a woman’s makeup kit: limited and flashy. Light blue buildings and windows border a hot pink street. A mauve fur-collared coat and a blackened-blue one clash and harmonize simultaneously, partly because the bodies of the women wearing them conform to each other like overlapping waves. Men in dark blue and black trench coats hover around these chic, high-end prostitutes, pretending to shop for something other than the women. The angular cityscape framing the crowd conforms to their shapes.

|

Figure 21-1: Kirchner stretched the figures in Street, Berlin, perhaps because the Berlin denizens strut down the avenue like peacocks; or maybe because their tall hats and feathered headdresses suggest that they want to add several inches to their stature. |

|

Street, Berlin, 1913. Ernst Ludwig Kirchner (1880-1938) © Copyright. Location: The Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY. Digital Image © The Museum of Modern Art / Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, NY.

Erich Heckel

Erich Heckel (1883–1970) was the chief organizer for Die Brücke and the glue that kept the group together during tough times. Without his efforts, Die Brücke wouldn’t have received the recognition they did; he arranged most of the exhibitions. Like the other members, Heckel’s paintings have a murky look, flattened perspective, and simplified forms.

Although Die Brücke didn’t paint antiwar or prowar paintings, the threat of war infects their art because it’s inside the artists. In Heckel’s 1908 painting Red Houses, the landscape and houses appear to feel the approach of an imminent catastrophe or apocalyptic storm like wild animals sense a fire or hurricane. As the war got closer, Heckel’s colors became murkier. After World War I (WWI) broke out in 1914, Heckel enlisted and became a medic in Belgium. While there, he painted Corpus Christi in Bruges. The ominous clouds in the painting look like mammoth mountains heaved up by the convulsions of the earth. The architecture is warped and frightened, and the handful of people roaming the yellow-green streets look as though they’re walking through a hallucination.

Der Blaue Reiter

Der Blaue Reiter, which began in 1911 in Munich, is the spiritual and bright side of Expressionism. The movement’s leaders, Russian-born Wassily Kandinsky and Franz Marc, sought to elevate mankind spiritually through a visual art that was allied to music. They believed man had sunken into a mire of materialism. For art to extract him from his materialistic rut, it must first shed its own materialism — in other words, the use of naturalistic forms. Der Blaue Reiter artists believed that, because naturalistic forms mirror the material world, they reinforce materialism rather than free people from it. In other words, a painting of a palace makes people want to live in it; a sculpture of a beautiful body stimulates thoughts of sex, not spirituality.

To achieve his spiritual goals, Kandinsky created a nonobjective or non- representational art. His subjects were his own inner tensions and emotions rather than landscapes or human models. He said, “The more obvious is the separation from nature, the more likely is the inner meaning to be pure and unhampered.”

Die Brücke artists didn’t have a lot to say about their movement. But the members of Der Blaue Reiter recorded their ideas in two books: the Blaue Reiter Almanac (see Chapter 28) and Kandinsky’s solo effort Concerning the Spiritual in Art.

Wassily Kandinsky: Symphonies of color

Wassily Kandinsky (1866–1944) believed that spiritual communication required a new language, so he invented a language of color. Paintings have always used color, but until the 20th century, color was subservient to form. For color to communicate effectively, Kandinsky believed it had to be freed from form in nonobjective art. His predecessors van Gogh, Gauguin, and the Fauves had moved in that direction. But they didn’t go far enough — they left color still locked inside representational forms.

In Concerning the Spiritual in Art, Kandinsky claims that the arts are gradually converging: “There has never been a time when the arts approached each other more nearly than they do today, in this later phase of spiritual development.” He said all the arts tended to borrow from music:

A painter, who finds no satisfaction in mere representation . . . in his longing to express his inner life, cannot but envy the ease with which music, the most non-material of the arts today, achieves this end. He naturally seeks to apply the methods of music to his own art. And from this results that modern desire for rhythm in painting, for mathematical, abstract construction, for repeated notes of color. . . .

In his painting Composition Number VI (see the color section), Kandinsky puts these ideas into practice. Instead of combining mostly garish colors like the Die Brücke artists and the Fauves, he juxtaposes friendly colors (greens and blues) to create harmonious blends mixed with clashing colors (vivid reds and toned-down yellows), which create discords that suggest frenzied motion. Composition Number VI feels like the climax of a jazz jam with cymbal crashes, rousing rhythms, and blaring horns. It’s an exploding concert of colors that soothes and stirs you up simultaneously. The impression of organized chaos conveys Kandinsky’s message of freedom from form. Yet if you look hard enough, the painting begins to resemble natural scenery — perhaps a Bavarian mountainscape during a riotous Mardi Gras. Despite its freeform feel, Composition Number VI (one of a series of compositions that Kandinsky painted) is not randomly composed; each color is as carefully chosen as the notes in a Mozart symphony.

Franz Marc: Horses that harmonize with the landscape

At first, Franz Marc (1880–1916) was less abstract than his fellow Der Blaue Reiter member Kandinsky. He felt true spirituality could be achieved by returning to nature, to the primitive. So he painted animals because, to him, they represent purity untainted by society. In a letter to his wife, Marc wrote:

Instinct has never failed to guide me . . . especially the instinct which led me away from man’s awareness of life and towards that of a pure animal. The ungodly people who surrounded me (especially the male variety) did not inspire me very much, whereas an animal’s unadulterated awareness of life made me respond with everything that was good in me.

The color combinations of the Fauves, especially Derain and Vlaminck, showed Marc that color can be freed from the object. In other words, an artist didn’t have to use naturalistic colors. Marc began to paint his famous blue horses, a purple fox, and a bright yellow cow. However, from 1913 until his death in WWI, Marc moved toward pure abstraction (nonobjective art).

Horse Dreaming, painted in 1913, is a bridge between his more realistic work like The Yellow Cow and The Little Blue Horses, and his later abstract work. In Horse Dreaming, the representational (realistic) elements are not more or less important than the abstract ones. Marc perfectly balances the two. To harmonize the representational horses with the abstract circles, cylinders, and triangles that surround them, he simplified the horses into geometric units. Both the abstract and representational elements look like geometry problems. But these problems can only be solved through the imagination. For example, abstract green and red shards pierce the large blue horse without wounding it. Are the shards merely the “stuff that dreams are made on”? The mysteriousness of the painting draws you into the horse’s dream so that it becomes your own.

Austrian Expressionism: From Dream to Nightmare

In Austria, Expressionism grew out of Art Nouveau (see Chapter 20). The leader of Austrian Expressionism, Gustav Klimt, launched a reformist art movement in 1897 called the Secession or the Vienna Secession. The goal of the Secession was to secede from the restrictive academic art world in Vienna and create what they wanted to create. Their motto: “To the times its art; to the art its freedom.” This goal didn’t change when the Secession evolved from an Art Nouveau (Jugendstil) movement into the Austrian Expressionist movement.

The Secession raked in enough money from its first Exhibition (staged in a building of the horticultural society) to buy their own building. They used it to showcase all the arts, which they believed were allies. Like Les XX in Belgium (see Chapter 20), the Secession hosted literary readings and concerts of Arnold Schoenberg and other contemporary composers’ music. They also published a monthly magazine Ver Sacrum (Sacred Spring), which included articles about art and architecture as well as drawings and poetry by great poets of the period, including Rainer Maria Rilke. Also, like Les XX, they held international exhibitions featuring works by Édouard Manet, Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Paul Cézanne, Vincent van Gogh, Auguste Rodin, Paul Signac, and others.

Gustav Klimt and his languorous ladies

Sigmund Freud wrote, “The interpretation of dreams is the royal road to a knowledge of the unconscious activities of life.” His Viennese contemporary, Gustav Klimt (1862–1918), explored people’s dreams, too, but with a paintbrush.

Watersnakes (see the color section) appears to be a decorative, sensual dream of two female lovers. The painting has an underwater feel, which makes it even dreamier, emphasized by the fluid forms of the women or watersnakes, the white and gold flowerets swaying like seaweed in unseen currents, and the passerby whale oozing into the picture on the lower right.

In this and other paintings, Klimt glorified female sexuality by embedding it in a gorgeous ornamental background like an exotic jewel set in gold filigree. But the background of swirls and circles of gold isn’t merely decorative; it is also subtly symbolic. For example, the small circular shapes in the painting (white, gold, and black) are actually ova raining through the lovers’ dream like pollen.

The painting is done in Klimt’s famous gold style, which he developed after visiting Venice and Ravenna in 1903. The gold-encrusted ceiling of St. Mark’s in Venice, the glittering Justinian and the Theodora mosaics (see Chapter 9) in Ravenna, and Byzantine icons in general deeply inspired him. Klimt mixed the Byzantine style with his other influences, in particular Art Nouveau (and the drawings of Aubrey Beardsley) and Symbolism, creating a new, jewel-like manner of painting. He transformed the classic Byzantine icon into icons of sensuality. He didn’t merely wrap his figures in a golden aura like Byzantine artists did; instead, he blended them into his shimmering background with decorative motifs.

In one of his greatest gold-style paintings, Adele Bloch-Bauer I, Klimt flattened the woman’s dress so that it shares the same picture plane as the background. Then he blended them together by merging the decorative dress with an equally decorative background. Yet the dress is still distinguishable from the background. Actually, the painting has two backgrounds: a flat gold wall, and a golden membrane or ornamental cocoon wrapped around Ms. Bloch-Bauer. Sinuous lines, swirls, and large and tiny squares distinguish the membrane from the dress, which is comprised of silver arrowheads, and gold pyramids with eyes in them. The latter give the impression that the dress is watching us. But the woman’s face, neckline, hands, and forearms are classically modeled, so that she emerges from the background and her own flattened body as a three-dimensional woman.

Egon Schiele: Turning the Self inside out

The early canvases of Egon Schiele (1890–1918) show the influence of Klimt, who was a father figure to the younger artist. (Schiele’s own father died of syphilis when Egon was 15.) But Schiele soon shed the Klimt glitter and dreaminess to express his own brilliant but dark visions and anguished eroticism.

Self-Portrait Pulling Cheek shows the artist’s characteristic expressive swirling brushstrokes painted with thinned out watercolor (or oil). This technique exposed some of the paper underneath. Schiele’s art is an art of exposure. He exposed his model’s and his own innermost tensions and anxieties, probing sexual obsessions like an angst-ridden version of Freud. He used hard-edged contours and murky colors to reveal the anxieties, fear, and depression of his model-patients, who usually looked starved.

The viewer feels that Schiele has turned eroticism and his own mind inside out, exposing everything. Sex in Schiele’s paintings is an act of desperation between beings so knotted up that entwining with another person can’t relieve the tension of either lover.

Schiele and his wife and unborn child died in 1918 from the Spanish flu, which swept away over 20 million lives that year.

Oskar Kokoschka: Dark dreams and interior storms

Oskar Kokoschka (1886–1980), another great Austrian Expressionist, explored the dark side of human nature like Schiele. He held a profound admiration for Klimt, and the older artist’s influence is apparent in his early work. Kokoschka’s Bride of the Wind, painted at the outbreak of WWI, looks like a golden Klimt dream turned into a black nightmare. Instead of being sweetly entwined, the bodies of the nude man (the Wind) and bride cocoon desperately together. The painting is a metaphor for Kokoschka’s intense love affair with Alma Schindler, the widow of composer Gustav Mahler and future wife of Walter Gropius, founder of the Bauhaus (see Chapter 23). She ended their affair and aborted their child. A year later, Alma learned Kokoschka had been mortally wounded in WWI. But he recovered in 1916 and returned to find her married to Gropius. His love for her became an obsession; he had a doll made of her, which he lugged around Vienna and used as a model for some of his paintings (the story is recounted in the 2001 film Bride of the Wind).