Chapter 24

Anything-Goes Art: Fab Fifties and Psychedelic Sixties

In This Chapter

Tuning in to 1950s art

Tuning in to 1950s art

Turning on to 1960s Pop Art and Minimalism

Turning on to 1960s Pop Art and Minimalism

Focusing on Photorealism

Focusing on Photorealism

Discovering performance art

Discovering performance art

After World War II, the in-your-face prospect of nuclear annihilation gave new meaning to the expression carpe diem (“seize the day”). Affluent Americans invented a throwaway culture that spread across the planet like both a fad and an epidemic. In the ’50s and ’60s, some artists reacted to the throwaway society, the Cold War, and Abstract Expressionism by reviving Realism, perhaps as a return to stability. Some blended the arts, as if one art form wasn’t enough to express the chaotic variety of modern life; others turned to here-today-gone-tomorrow pop culture — movies, comic books, detective novels, and rock-’n’-roll — for inspiration.

In this chapter, I cover Pop Art, Color Field Art and Minimalism, Fantastic Realism, Photorealism, and performance art. I also give you a brief look at decorative arts that evolved into high arts.

Artsy Cartoons: Pop Art

Traditionally, popular culture and high culture didn’t dine in the same restaurants, attend the same concerts, or look at the same art. Pop Art changed that by blurring the cultural divide between the classes.

The Pop Art movement began in England. But it was always about the United States, where egalitarianism had the deepest roots and where throwaway culture came of age first.

The first Pop Art picture (a collage), Richard Hamilton’s Just What Is It That Makes Today’s Home So Different, So Appealing? (1956), celebrates and parodies the U.S. cultural invasion of the U.K. Even the title mimics an American advertisement. The “appealing” home is stocked with the latest American conveniences — a reel-to-reel tape recorder, canned ham, a Ford Motors lampshade, a cartoon-strip poster, a tacky orange couch, a TV featuring an attractive woman on the telephone, and a portable vacuum cleaner with a superlong attachment hose. Its length is noted, as it would be in an ad, with a black pointer midway up the steps: “Ordinary cleaners reach only this far.” (To exaggerate its length, the staircase has its own vanishing point, which the hose practically reaches.) The main attractions are the nearly naked beefcake man, posing next to the reel-to-reel, and the cheesecake woman perched on the couch as if for a Playboy camera. Outside the apartment window, the Warner Theater advertises an American movie, a rerun of Al Jolson’s The Jazz Singer, the first talkie (movie with sound). The only remnant of British culture in the home is the black-and-white Victorian portrait above the television.

In the following sections, I cover the art of two of the most influential Pop artists, Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein.

The many faces of Andy Warhol

You could say that Andy Warhol (1928–1987) looked at life backwards, and that his art tempts viewers to do the same. In his book The Philosophy of Andy Warhol, he wrote:

People sometimes say that the way things happen in the movies is unreal, but actually it’s the way things happen to you in life that’s unreal. The movies make emotions look so strong and real, whereas when things really do happen to you, it’s like watching television — you don’t feel anything.

Warhol’s paintings give the viewer an inside-out picture of popular culture by elevating the mundane (a soup can, a box of Brillo pads) into art. With his first Pop Art experiments — paintings of Campbell’s soup cans, Brillo pads, and Coca-Cola bottles — Warhol practically transplanted supermarket shelves into art galleries. The paintings look like advertisements for the products they depict. Warhol’s brand of art raises an obvious question: Is Pop Art “high art” in the same way that the Sistine Chapel Ceiling is? Warhol offered an ironic answer that has nothing to do with elevation:

Business Art is a much better thing to make than Art Art, because Art Art doesn’t support the space it takes up, whereas Business Art does. (If Business Art doesn’t support its own space it goes out-of-business.)

Warhol’s savvy blend of business and art grew out of his early success as a graphic artist/commercial illustrator in New York. His floating shoes and flashy, stylized flowers were the rage in fashion magazines long before he started cloning commodities for art galleries.

One thing is certain: Growing up as a poor kid in Pittsburg, Warhol was obsessed with money. He was fascinated by how people crave all those glitzy objects in storefront windows. He commoditized his own painted products by generating series of them. Now you could purchase a single canvas and get from six to a hundred cans of soup!

He took up the commercial silk-screen process of printing because it had an assembly-line efficiency, enabling him to manufacture art like any other commodity (even though no two images are exactly alike). To better market his work, he founded an art “factory,” further highlighting the relationship between art and business.

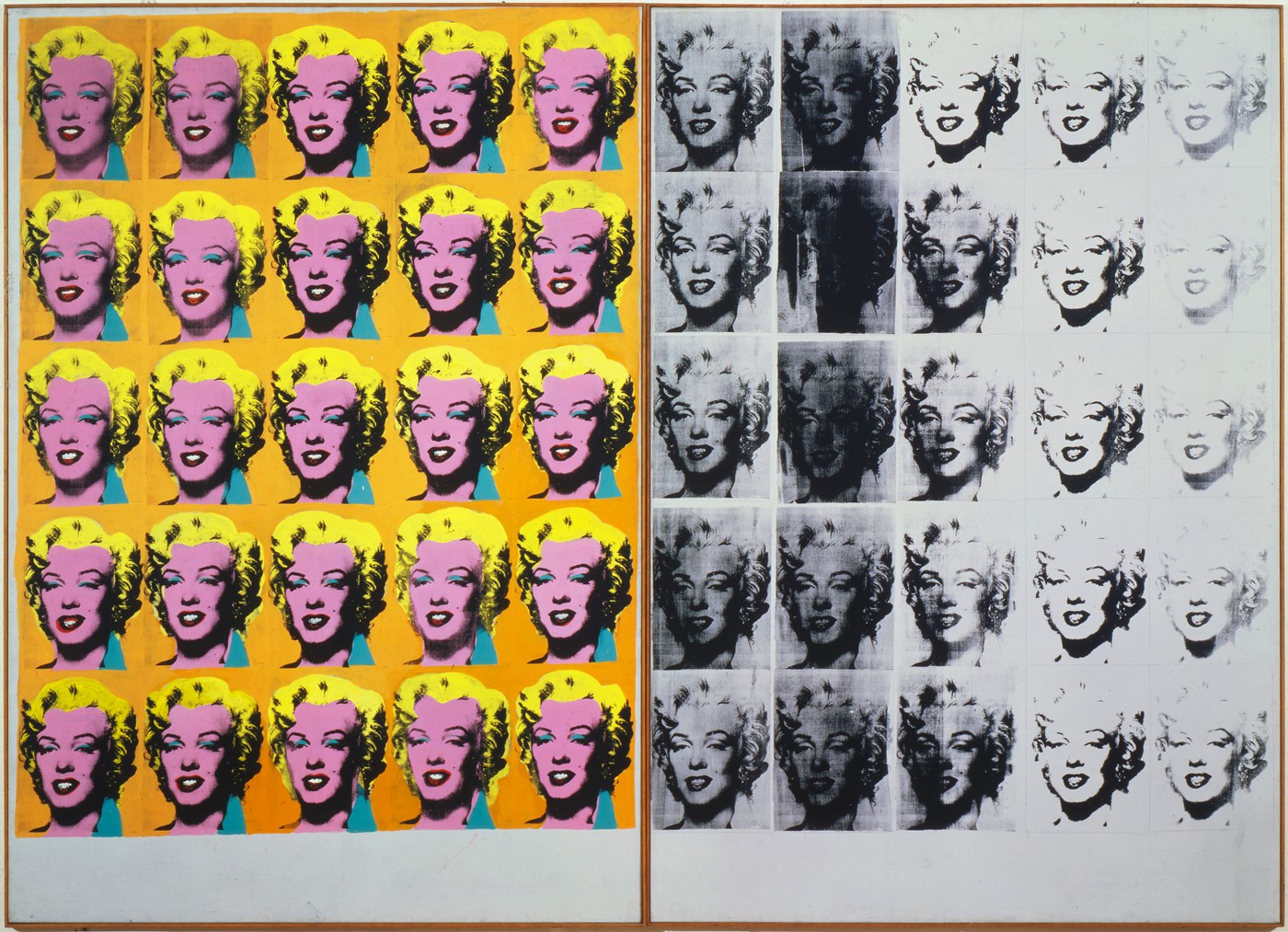

Celebrities are the commodities of Hollywood, and Warhol soon began silk-screening photographs of Elizabeth Taylor, Marilyn Monroe (see Figure 24-1), Elvis Presley, and other stars. He packaged them as Pop cultural icons, similar to Byzantine icons (see Chapter 9).

By depicting movie stars in a Byzantine-icon format, Warhol shows us our rather upside-down view of modern life. We put stars on pedestals so we can worship them as saints or gods. Ironically, even though Warhol seems to mock this modern-day mania, he was as star-struck by Marilyn and Elvis as anybody else.

|

Figure 24-1: Andy Warhol silk-screened his Marilyn Diptych in 1962 shortly after Monroe’s death. Shocking, neonlike colors lend the star a kind of artificial immortality. |

|

Tate Gallery, London / Art Resource, NY. © 2007 Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Blam! Comic books on canvas: Roy Lichtenstein

If Warhol could paint soup-can labels and call it art, Roy Lichtenstein (1923–1997) would make comic strips museum worthy. Maybe he could draw funny-paper readers into galleries by speaking to them in their own language. Although there are differences between Lichtenstein comics and the ones you find in the Sunday newspaper, the similarities are what strike you first. As in typical comic strips, Lichtenstein avoided shading, employed primary colors and thick black outlines, and used Benday dots to simulate high-speed newspaper color printing. The comic-strip look is perfect.

One difference between Lichtenstein’s paintings and the Sunday comics is that Lichtenstein focused on tense moments, ignoring what leads up to them and what follows. It appears as though he extracted the climactic episodes from comic strips and suspended them, leaving the outcome forever in the balance. In The Kiss, a weeping blonde embraces a debonair man who seems to return her love. But is it a reunion or farewell? Lichtenstein lets the viewer write the ending — and the beginning, for that matter.

In Foot and Hand, two extremities fight it out over a pistol, but no personalities are attached to the hand or the cowboy-booted foot. The color contrasts — red, yellow, pink, black, and white — and the graphic starkness in the painting heighten the tension. You can’t determine who the good guy is or if they’re both bad. And you don’t know why the hand and foot are fighting or who will win. But the list of possible outcomes is quite short, because the scene is lifted from a cliché comic-book Western. Lichtenstein said, “I’m interested in what would normally be considered the worst aspects of commercial art. I think it’s the tension between what seems to be so rigid and clichéd and the fact that art really can’t be this way.”

Another difference between Lichtenstein’s work and traditional comic strips is in Lichtenstein’s attitude. Pop artists felt that Abstract Expressionists inserted themselves too much in their art — that they were overly expressive. Lichtenstein wanted to withdraw from his paintings (or appear to step back) and let the work’s formal qualities and tensions speak for themselves. He said that he aimed for “the impersonal look. . . . What interests me is to paint the kind of antisensitivity that impregnates modern civilization.”

Fantastic Realism

The Fantastic Realists were inspired by the Vienna Secession movement (see Chapter 21), by Surrealism, and by their teacher Albert Paris von Gütersloh at the Vienna Academy of Fine Arts. Ernst Fuchs, Erich Brauer, Wolfgang Hutter, and Anton Lehmden launched the movement just after World War II.

At first, Fantastic Realism appeared to be an offshoot of Surrealism, with its emphasis on dreamlike, highly imaginative imagery and unconscious symbolism. But Fuchs and the others soon concluded that they weren’t Surrealists. They were interested in how the conscious mind interprets unconscious activity, not in letting the unconscious dictate their choice of imagery as the Surrealists did (see Chapter 23). Fuchs said:

I have always practiced a kind of art which depicts things that, otherwise, man only sees in his dreams or hallucinations. For me, the threshold has to be crossed from inner images to their expression in wakeful being.

In the following sections, I explore the Fantastic Realist paintings by Ernst Fuchs and the art and architecture of Friedensreich Hundertwasser.

Ernst Fuchs: The father of the Fantastic Realists

Ernst Fuchs (1930–) combines fantastic imagery and symbolism with sharply defined realistic depictions. His paintings look like a marriage of Surrealism and Symbolism.

After his conversion to Catholicism in 1956, Fuchs depicted religious themes in Fantastic Realist environments. In his 1957 drawing Christ Before Pilate, Fuchs recounts several episodes of Christ’s Passion (the final hours of Christ’s life) simultaneously, suggesting that the mind condenses related events into a single image and moment. On the left, Pontius Pilate, who wears a skirt, breast plate, and bishop’s miter, interrogates Jesus. In the center, the figure of Death gallops toward Christ on the back of a grisly faced unicorn. A miniature German soldier toting a Luger pistol has hitched a ride. Fuchs employs traditional perspective in this part of the drawing. But on the right, an empty Last Supper table (with a crucifix growing out of it) recedes toward its own vanishing point, implying that another related spiritual event occurs simultaneously within its own system of linear perspective. The walls flanking the table encase bizarre figures from yet another dimension: a howling phantom with an Asian face in his belly; a lion-headed, lanky man; and an elongated skeleton with an old man’s mug.

Hundertwasser houses

The straight line is something cowardly drawn with a rule, without thought or feeling; it is a line which does not exist in nature.

—Friedensreich Hundertwasser

Friedensreich Hundertwasser (1928–2000), painter and architectural philosopher, declared war on the straight line, the square, and other forms not readily found in nature. Hundertwasser believed that blocks reflect uniformity and have a heavy, static feel, while fluid, organic shapes suggest the change and infinite variety of nature.

He also felt that uniform environments — in particular, the grid apartment complex — mold people into uniform lifestyles. In a Hundertwasser building, each apartment is unique, to encourage individuality.

Hundertwasser also banned the traditional rectangular window from his architecture. “The repetition of identical windows next to each other and above each other as in a grid system is a characteristic of concentration camps,” he wrote in his essay, “Window Dictatorship and Window Right.” In one of his designs, the Eye-Slit-House, a home built into a hillside has a single window that peeks out of the grassy slope like an ever-alert eye.

Hundertwasser not only used organic shapes and lines, but also incorporated pieces of nature into his structures. His designs typically call for rooftop gardens and, in one case, grazing cows. He insisted that apartment buildings set aside space for “tree tenants.” He explained tree tenants this way:

The tree tenant symbolizes a turn in human history because he regains his rank as an important partner of man. . . . Only if you love the tree like yourself will you survive. We are suffocating in our cities from poison and lack of oxygen. We systematically destroy the vegetation which gives us life and lets us breathe.

He said that rooftop trees and lawns provide oxygen and serve as air filters, hold heat in the building in the winter and cool it down during the summer, thereby reducing fuel costs.

Several of Hundertwasser’s structures have been erected in and around Vienna. His most famous, the Hundertwasser Haus (see Figure 24-2), includes rooftop tree parks on multiple levels. He diverges from the traditional grid structure by giving each apartment a unique organic shape and painting the stone facade in lively pastel colors.

|

Figure 24-2: The Hundertwasser Haus in Vienna was built to provide middle-class people with beautiful, highly creative housing that promotes individuality. |

|

Erich Lessing / Art Resource, NY

Hundertwasser is also one of the top post-WWII Austrian painters. His art tends to reflect his architectural theories. People, buildings, and landscapes overlap and sometimes blend on his canvases. In The 30-Day Fax Painting, a bright red street winds through people’s heads, faces become windows in buses and buildings, a statuesque traffic cop with a face for every intersection grows out of a building, and a gigantic man has contiguous blue-eye slits, multiple sets of blue lips, and about 20 bright yellow boats gliding across his wavy, sea-blue chest. Hundertwasser uses the bright, unmixed colors of a child’s palette in most of his paintings, and contour lines that flow through faces, buildings, streets, cars, and buses, blending everything in candy-colored streams.

Less-Is-More Art: Rothko, Newman, Stella, and Others

Mark Rothko (1903–1970) and Barnett Newman (1905–1970) steered Abstract Expressionism in a very different direction. You could say they boxed it up. Instead of splattering colors over their canvases like crazed kids with finger paints, they painted one color or a few colors in clearly defined rectangles. Because they painted broad areas of one color, they are called Color Field painters.

Color Fields of dreams: Rothko and Newman

Mark Rothko wanted his boxes of color to fight and be friends at the same time. He tried to wed two contrasting forms of creativity — the orderly kind (form) and the wild side (expression) — inside his paintings. His boxes are meant to represent both aspects in a variety of relationships.

The German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche identified these creative modes in his work The Birth of Tragedy, calling the orderly side Apollonian (after the God Apollo, god of the sun) and the wild side Dionysiac (after Dionysus, the god of wine and ecstasy). Dionysus breaks down barriers so that the energies and essences of things can merge. Apollo erects barriers that contain and restrain energy. Nietzsche contended that great art must be a balance of both: “Art owes its continuous evolution to the Apollonian-Dionysiac duality, even as the propagation of the species depends on the duality of the sexes, their constant conflicts and periodic acts of reconciliation.”

In some art, one god may appear to have the upper hand. At first look, you’d think that Jackson Pollock had kicked Apollo off his canvases; Dionysus is clearly in charge of the fireworks. But even Pollock has an Apollonian side, a sense of orderly composition.

The Color Field painters, on the other hand, seem to have evicted Dionysus. How can a rectangle express anything? But Rothko’s boxes argue with each other and vibrate around their edges. Sometimes he butts complementary color fields against each other, creating color wars. More often, Rothko paints harmonious (analogous) color fields close to each other, as in Untitled (Violet, Black, Orange, Yellow on White and Red). Because the colors are harmonious, they want to blend, but Rothko won’t let them. This creates tension and establishes the visual equivalent of a magnetic pull between color fields. Barnette Newman’s boxes are even more reductive than Rothko’s. Frequently he used only one color to represent the human condition. But he divided his monochromatic squares and rectangles with vertical (and occasionally horizontal) lines that he called “zips.” Zips can serve as abstract stand-ins for human beings who split space yet remain part of it. Newman said he hoped viewers of his work would experience an “awareness of being alive in the sensation of complete space.”

Newman’s Dionysius is a large green rectangle with two horizontal zips. Does the canvas embody the Dionysic experience described earlier — uninhibited wildness — with only two Apollonian interruptions (the zips)? It does encourage the mind to wander freely in all directions over its vast (67-x-49-inch) green expanse.

Minimalism, more or less

Frank Stella (1936–) founded the Minimalist movement in the late 1950s and was soon joined by artists such as Richard Serra (1939–), Agnes Martin (1912–2004), and Robert Ryman (1930–). Stella’s goal was to tone down the visual explosions of the Abstract Expressionists. Like so many artists since Post-Impressionism, he believed that art was a process of reduction: Life should be broken down into its fundamental forms.

The Minimalists took this concept farther than anyone had before. They threw out almost all expressive forms: organic shapes, visual metaphor, symbolism, emotions, and often color or shades of color. With this very limited arsenal of expressive tools, they created highly formal compositions.

In Frank Stella’s Avicenna, a white rectangle cut from the center of the composition is surrounded by a grid of radiating, crenellated lines. Ironically, Avicenna was one of the world’s greatest and most versatile scholars. The painting may suggest the scholar’s formalism, but it doesn’t reflect his versatility. Repetition and contrast are the only elements of design that Stella used. To further depersonalize his work and give it a made-to-last look, Stella used industrial paint (in this case, aluminum paint).

Minimalist sculptor Donald Judd (1928–1994), who believed art shouldn’t represent anything, often repeated identical units of quadrangles with little or no variation. Although these sculptures strike many people as monotonous, reducing the artwork to such sparse extremes can make the viewer sensitive to surface, volume, and the space around the object. Judd’s Untitled (1969) is a stack of what appear to be blue shelves projecting from a wall. The piece is reminiscent of an open filing cabinet in a high school, but its rigid, formal elegance would prevent most people from storing their files there.

The next step in Minimalism is probably the dead end. At a certain point, reduction leads to nothingness. Most Minimalists changed directions before reaching that point. In the 1970s and 1980s, Stella rejected minimalism and dramatically expanded his visual vocabulary. Colors explode from his Post-Minimalist canvases in expressive writhing shapes that look like scrap metal and fractured engines.

Photorealism

Like Pop Art, Photorealism (primarily an American movement) signaled a return to representational art. The realism in Photorealistic art is so striking and yet so painterly that you’re taken in by the illusion and aware of the artist’s process at the same time.

Photorealists like Richard Estes (1936–), Chuck Close (1940–), Audrey Flack (1931–), Don Eddy (1944–), and Philip Pearlstein (1924–) use photographs as their models. But they don’t simply transcribe photos. The goal of Photorealists is to detach themselves from their subjects, to present an objective impres- sion of ordinary life, the way an alien might view humans. For example, Philip Pearlstein might begin a painting with a foot and work his way up the body until the canvas prevents him from including an arm or the head. Pearlstein says he prefers leaving off the head — it helps depersonalize his nudes.

In the following sections, I examine the work of Richard Estes and Chuck Close.

Richard Estes: Always in focus

Looking at a Richard Estes painting makes you feel as though your vision has improved. He turns up the intensity on reality.

He also highlights a building’s geometric patterns and emphasizes color relationships by manipulating his photos as he did in Seagram Building, from the series Urban Landscapes 1 (1972). Estes is a master at depicting reflections. The reflective effects in his paintings evoke a sense of super-reality because you see the reflections sharply from all angles at once — impossible to do with the naked eye, even if you have had LASIK eye surgery.

Clinical close-ups: Chuck Close

After a short stint as an abstract painter, Chuck Close became a Photorealist, painting black-and-white paintings from color photographs, then color paintings from black-and-white photographs. Typically, he works in large scale to force the viewer to see his portraits in pieces, to explore a face like geographical terrain. His 1960s works are precise renderings of photos; sometimes the paintings are indistinguishable from the photographs (except for the enlarged scale). In the mid-1970s, Close’s style evolved into a probing portraiture that gives the viewer macroscopic and microscopic views of the human face at the same time. Since the late 1970s, he has broken up his portraits into the painterly equivalent of pixels. From up close (in his color portraits), these “pixels” look like small pieces of millefiori glass (colorful glass filled with circles of variegated colors). Close sometimes includes a third layer by breaking up the face into larger rectilinear units that contain the pixels, as in his portrait James. In this way, you see the face as three superimposed levels — a conventional photographic image, a dot-image impression, and a rectilinear image — each layer depicted with quasi-photographic precision.

Performance Art and Installations

Who said visual art has to be stuck on a canvas or pedestal? Imagine if all the characters in a crowded, rambunctious Rubens canvas jumped out of the painting and stormed the museum. Would it still be art? Or would it be thea- ter? Or a combination of both? Performance artists raised these questions and tested them in front of live audiences in the 1960s. Like Dadaists, they preferred active art that challenged traditional views of life and art. Some performance artists tried to re-create an atmosphere similar to primitive ritual, involving audiences as much as the artist in a transformative experience.

In the following sections, I check out the performance art of Fluxus and Joseph Beuys.

Fluxus: Intersections of the arts

Interdisciplinary and international, Fluxus artists — Joseph Beuys (1921–1986), Yoko Ono (1933–), Dick Higgins (1938–1998), George Brecht (1924–), Al Hansen (1927–1995), and Nam June Paik (1932–2006) — blended poetry, painting, music, and theater into multimedia performances. The Dada movement and especially Marcel Duchamp were major influences. Founder George Maciunas said Fluxus was a “Neo-Dada” group (see Chapter 23) with an anti-commercial art focus.

Often, performance artists used readymade materials to register their disapproval of commercial art. Fluxus typically employed boxes that had to be opened to reveal one or more secrets. The artists stuffed the boxes with cards, notes, letters, and games, and later exposed the contents, sometimes while playing musical tracks. The idea was to treat ordinary things contained in the box as if they were as worthy of musical accompaniment as the entrance of a king.

Joseph Beuys: Fanning out from Fluxus

Joseph Beuys, a German performance artist, activist, sculptor, and teacher, believed the world is in a spiritual crisis that art can help heal. He also believed all the arts should be merged into a single ritualistic force. To that end, in 1974 he founded the Free International University for Creativity and Interdisciplinary Research.

Beuys felt there was a breakdown between scientific and spiritual thinking and attempted to close the gap through shamanistic or ritualistic performances. He believed in the universal power of creativity and that, through a kind of resonance, one person’s creativity can awaken another’s.

More importantly Beuys felt that life is a social sculpture that everyone helps to shape. His performances, which he called Actionen, were intended to inspire conscious and positive shaping.

The Golden Age of American enameling

Until about 1935, most Americans viewed enameling as merely ornamental, good for decorating jewelry boxes or cigarette cases, but that was about it. However, in Europe, especially France, enameling has a long history as a high art form, particularly in Limoges where enamel paintings have been created since the 16th century.

An American enamel awakening began in the 1930s thanks largely to the work of three innovative enamel artists — Kenneth Bates (1904–1994), Edward Winter (1908–1976), and Karl Drerup (1904–2000). The next generation of enamelists, many of them Bates’s students, built upon their work, taking enameling in still more innovative directions.

Kenneth Bates, known as the Dean of American Enamelists, more than anyone spread enameling as an art form across the United States through his work and his teaching. In one of his best pieces, Argument in Limoges Market Place, Bates incorporates Cubist and Futurist designs into his semi-abstract representation of women arguing at a market in the great French enameling center, Limoges. The Cubist angularity and patterns and the Futurist fusion of images increases the tension of the argument. Even the houses seem to be squabbling. At the same time Bates dilutes the tension with his playful color palette of light blues and mauves, dark greens, browns, and reds.

Edward Winter, who studied enameling under Bates and in Vienna at the Viennese Workshop (Wienerwerkstette), brought purely abstract European enameling styles to the States. His elegant abstractions typically feature subtle grades of color that suggest layers and transcendental perspectives. In Textures in Pink and Brown, an abstract staircase unfolds inside a network of angular ridges of color intersected by wavelets and graceful floral shapes. The multiple angles don’t quite harmonize with one another, but create subtle active tensions between the layers that keep the eyes swimming from shape to shape, level to level.

Art Estate of the late James M. (Mel) Someroski

Like Edward Winter, James Melvin Someroski (1932–1995) studied under Kenneth Bates and took enameling in still other directions, including activist art. Someroski’s Children of War series of 12 plique à jours — which look like miniature stained-glass windows — illustrate scenes from German concentration camps based on actual photos. In Never Again, an infant in a fetal position and two older children’s ghostly bodies rise from a crematorium smoke stack into a fiery sunset of intersecting waves of orange, yellow, and white light. The heavens are so enflamed and yet so glorious that it’s impossible to tell if the Nazis or God has set the sky on fire. Someroski said of these children: “I try to lift them out of the photos, lift them out of the crowds, the mass graves . . . resurrect them, wrap them in fine silver and gold, try to breathe life into them again. . . . In the chamber of an enamel kiln, in a new fire restore them.”

In 1965, after leaving Fluxus, Beuys performed How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare in the Galerie Schmela in Düsseldorf. He smeared his head with honey and stuck gold leaf to it, then cradled a dead hare in his arms while sitting in a corner of the gallery. Suddenly he rose and toured the gallery, explaining the pictures to the dead animal. Periodically, he interrupted himself to walk over a dead pine tree. (Hares, honey, and pine trees have spiritual and mythical meanings for Beuys and others.) Beuys later explained that his performance was a “Complex tableau about the problems of language, and about the problems of thought, of human consciousness and of the consciousness of animals.” He also said that a dead hare would grasp his explanations about art better than many people with “their stubborn rationalism.”

Beuys further tested the boundaries of art and rationality as a founder of the Conceptual Art movement of the late 1960s and early 1970s, pointing out some of the contradictions in how words and images communicate. However, not everyone was eager for art to surrender its materials and craft at the altar of performance and conceptual art. Some artists working in the decorative arts (also known as Arts and Crafts) were not only unwilling to abandon their crafts, they were determined to prove that painting, sculpture, and performance and conceptual art didn’t have a monopoly on high art. Glass artists like Harvey Littleton and Dale Chihuly, pioneering fiber artist Lenore Tawney, and enamelists such as Kenneth Bates demonstrated that the decorative arts can be more than just decoration. (See the nearby sidebar, “The Golden Age of American enameling” for more on the emergence of a decorative art as high art.)