1898: The Spanish-American War—Manifest Destiny Leaves the Continental US for the First Time

By the late 1800s, national territorial expansion was over. The railroads were built, and the supply chains were completed. Business was good, profits were there, but real corporate growth was no longer a reality. Other markets were needed for the country’s wealth and power to reach new heights. Lo and behold, the Cuban situation would be the road toward the emerging markets of Asia and Central America.

Born in 1863, William Randolph Hearst was the son of George Hearst, one of the richest men in America when the Civil War began. In 1887, George accepted the San Francisco Examiner as payment for a gambling debt, and his son became the proprietor. Through the years, the young Hearst became a newspaper and magazine magnate, acquiring the likes of the Chicago Examiner, Cosmopolitan, and Harper’s Bazaar. Besides building a castle in San Simeon, California, on a quarter million-acre ranch, William Randolph Hearst is probably best remembered for helping to inspire and ignite the Spanish-American War.

Newspaper columnist Ernest L. Meyer wrote, “Mr. Hearst in his long and not laudable career has inflamed Americans against Spaniards, Americans against Japanese, Americans against Filipinos, Americans against Russians, and in the pursuit of his incendiary campaign he has printed downright lies, forged documents, faked atrocity stories, inflammatory editorials, sensational cartoons and photographs and other devices by which he abetted his jingoistic ends.”77

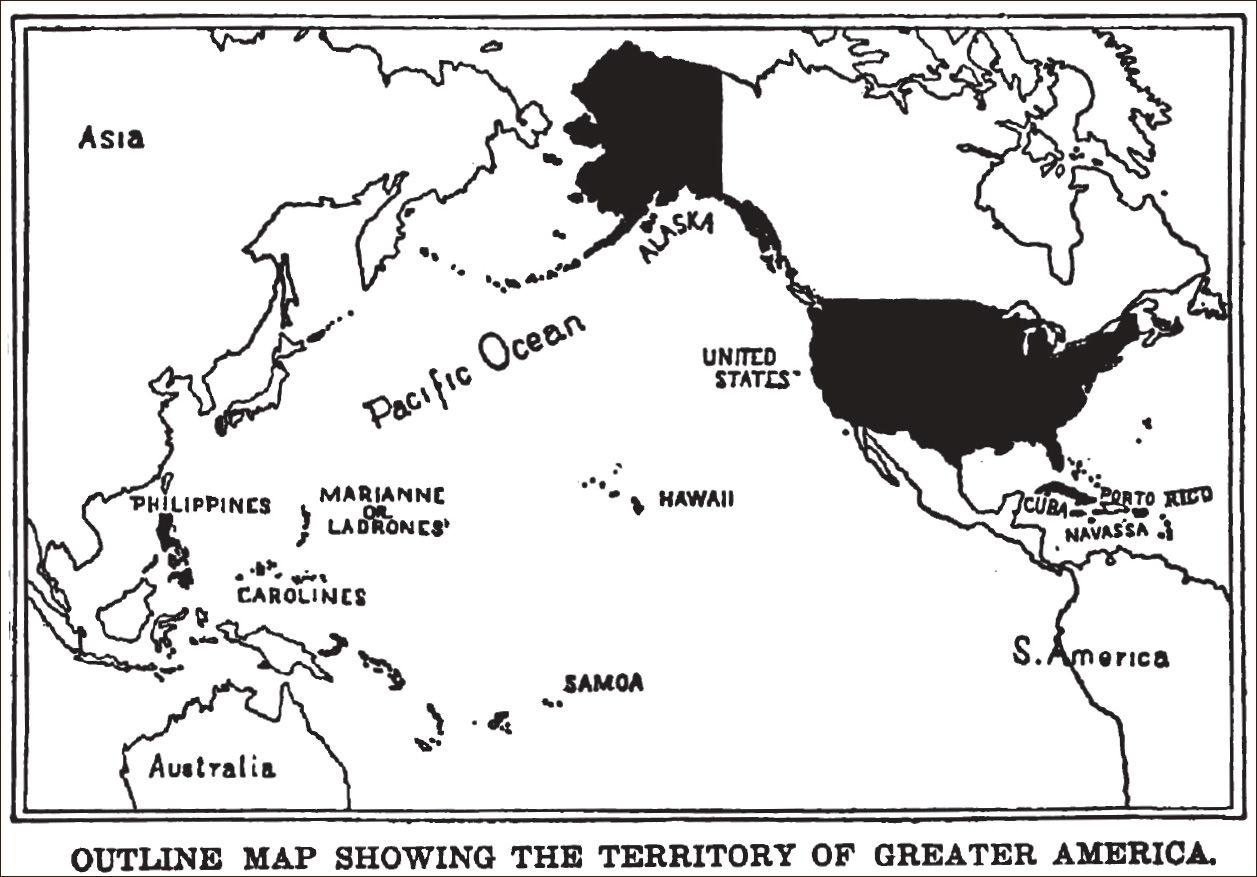

Hearst purchased the New York Journal in 1895 and promptly came into stiff competition with Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World. This rivalry had an enormous impact on the beginning of the Spanish-American War, which for all intents and purposes permanently dissolved the Spanish Empire, and gave Cuba, Hawaii, the Philippines, Guam, and Puerto Rico to the United States. America emerged as an international player, now with a foothold in Latin America and East Asia. And although the explosion and subsequent sinking of the USS Maine in Cuba’s harbor was the final straw, Hearst and Pulitzer’s yellow journalism paved the way.

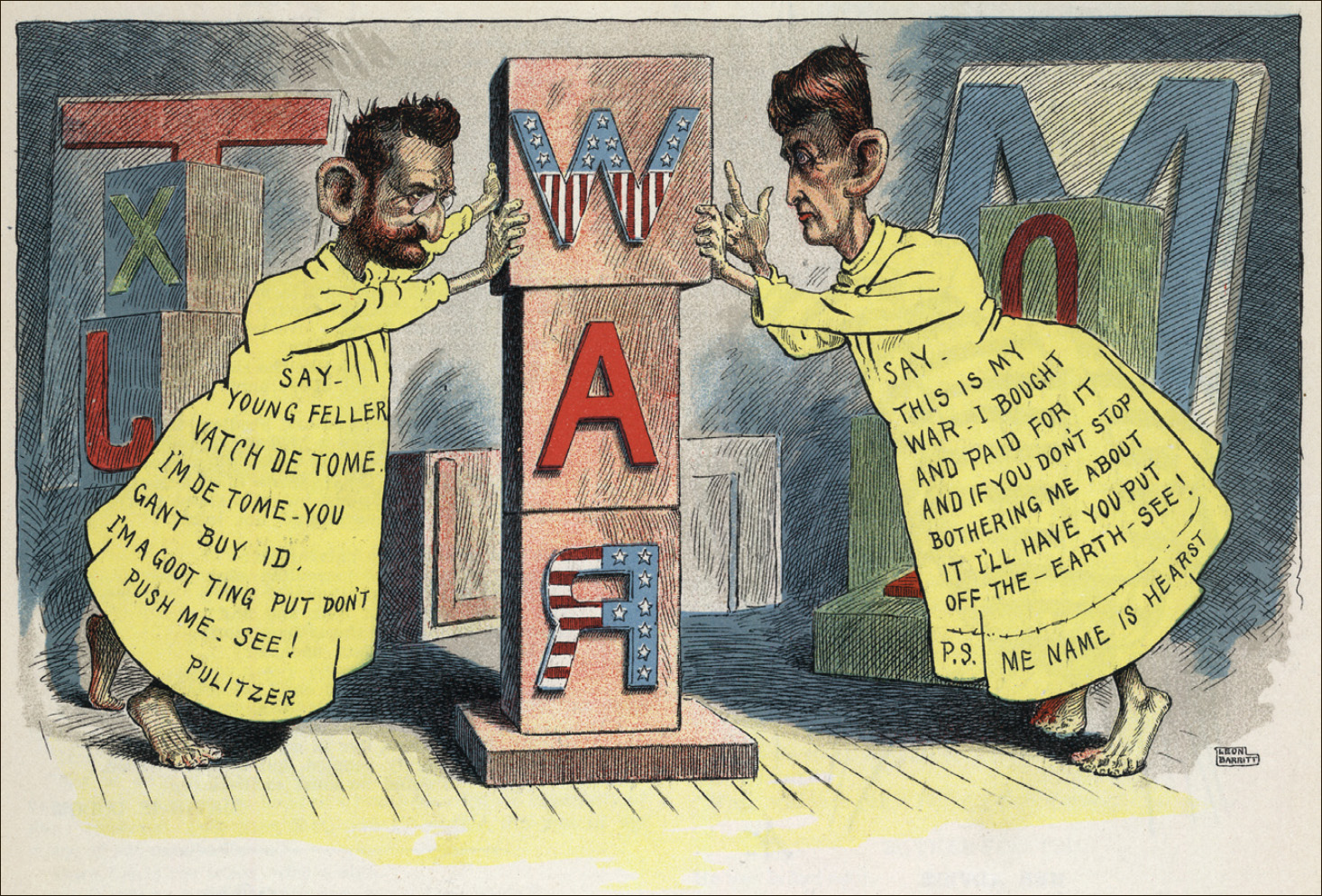

Newspaper publishers Joseph Pulitzer and William Randolph Hearst, full-length, dressed as the Yellow Kid (a popular cartoon character of the day), each pushing against opposite sides of a pillar of wooden blocks that spells WAR. This is a satire of the Pulitzer and Hearst newspapers’ role in drumming up USA public opinion to go to war with Spain. Leon Barritt, 1898.

Named after The Yellow Kid comic strip featured in both newspapers, Hearst and Pulitzer were staunch rivals, each one trying to outdo the other with sensational stories to draw circulation. At one point, Hearst reduced the cost of the paper to a penny, with Pulitzer immediately following suit. As sales increased, so did the public’s appetite for the sensational. Readers almost seemed to beg for new scandals, and the publishers accommodated.

The Cuban insurrection was the event that brought yellow journalism to a fever pitch. The rebels had fought bitterly for years against their Spanish rulers, and the Journal fervently declared its support. Hearst even refused to carry any news from the Spanish side, saying that only the revolutionaries could be trusted, turning the conflict into the Spanish villains versus the Cuban rebel heroes—probably the first example of good versus evil to inspire Americans for war.

There was no doubt Spain was oppressing Cuba with harsh rule, even placing many in concentration camps. But the two newspapers took advantage of it, with headlines plastered across newsstands such as “SPANISH CANNIBALISM” and “INHUMAN TORTURE.” In his memoir, James Creelman, a fan of Hearst, states that after Journal correspondent Frederick Remington arrived in Cuba to report on the conflict, he wrote back asking to return home since there were no signs of war. Creelman claims that Hearst replied, “Please remain. You furnish the pictures, I’ll furnish the war.” Presumably intended to compliment Hearst by showing the verve of yellow journalism, it most likely was a fabricated account since no source has ever been shown.78 It certainly illustrates how Hearst helped to precipitate a war.

Then, on February 15, 1898, three weeks after she arrived on a friendly visit, 260 US sailors were killed when an explosion rocked the USS Maine docked in Havana Harbor. Most newspapers called for patience and vigilance toward any US response, but the World and Journal published inflammatory rhetoric. Two days later, the Journal’s front page featured headlines offering a “$50,000 reward for the conviction of the criminals . . . Naval officers think the Maine was destroyed by a Spanish mine. . . .”79 The World claimed to have sold five million newspapers that week, and the public clamored for President McKinley to declare war. Editorials demanded that the United States act accordingly to avenge the deaths. The slogan “Remember the Maine! To hell with Spain!” echoed at the dinner table and in the Capitol and White House.

An inquiry immediately following the sinking concluded that the Maine was destroyed by an external explosion that triggered a subsequent magazine explosion. The official story of an external explosion eliminated the possibility that it was caused by an internal accident or sabotage from within. So, who blew it up? The Spanish government? Cuban rebels? Accidentally, by an old Spanish mine that somehow drifted into the harbor? The Weylerites, Spanish right-wing radicals who committed atrocities against the Cubans and were subsequently replaced by the government?

There was no geyser-like spout immediately following the explosion, and there were no dead fish floating around the ship. Both of those events almost certainly would have been likely signs of an external explosion. The AP, via the Humboldt Times on February 17, 1898, reported that “Most of the naval officers believe the explosion resulted from a spontaneous explosion in the coal bunkers. . . . Also listed as possible causes were a boiler explosion or overheating of an iron partition between the boilers and the ship’s ammunition magazine.”80

We’ll probably never know with any certainty how those 260 American sailors perished. But we do know that due to the sinking of the USS Maine and the subsequent three-month war, the United States became a world power, with a gateway to South and Central America via the Caribbean islands, and in the Pacific Ocean, oh so close to the Asian continent.

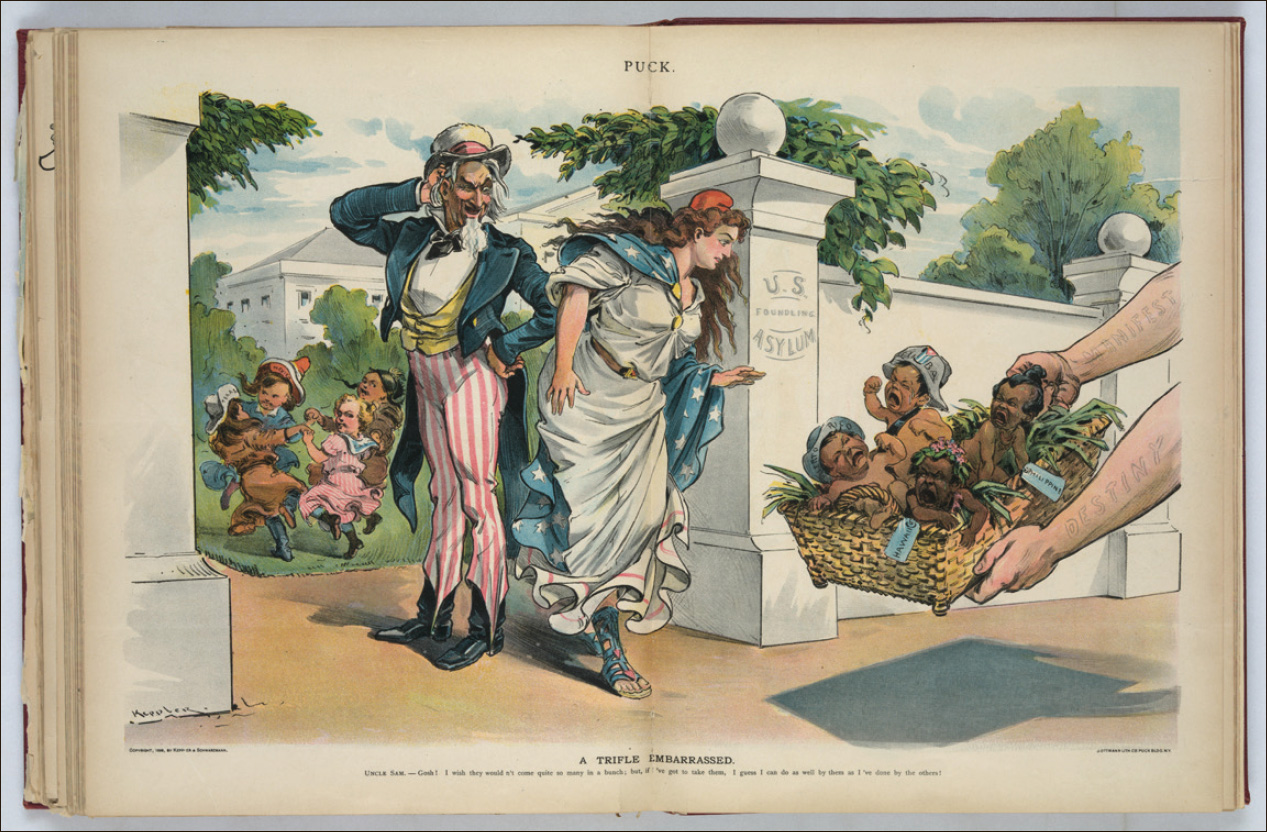

In April 1898, The United States Senate passed the Teller Amendment as an addition to the resolution of war which disclaimed any intention of the United States to exercise any jurisdiction over Cuba and asserted America’s determination to leave the government and control of the country to the Cuban people. In 1902, the Senate passed the Platt Amendment, which stated that US consent must be given for all Cuban treaties and trade agreements, and the United States was given “the right to intervene for the preservation of Cuban independence, the maintenance of a government adequate for the protection of life, property. . . .”81 It took America less than four years to reverse itself.

In 1890, United States investments in Cuba totaled $50 million, roughly 7 percent of all US foreign trade. Already by the 1880s, American capital was heavily invested in the Cuban economy and all the islands in the Caribbean, especially the sugar industry. The United States even offered Spain $100 million ($2.5 billion in today’s currency) to buy Cuba, a mere pittance compared to its actual worth. The Spaniards said no.

Cuban rebels were doing exactly what the Viet Cong accomplished more than a half century later. They were beating a highly experienced and well-equipped army, and in 1898, victory was near. America not only couldn’t, they wouldn’t allow the Cuban rebels to win and seize control of their country. It was in the best economic interests of America not to have a sovereign Cuba. The United States government never recognized Cuba’s fight or its right to independence. It never recognized the Cuban people’s struggle as a legitimate force. In his message to Congress on April 11, 1898, asking for war with Spain, President McKinley stated, “Nor from the standpoint of expediency do I think it would be wise or prudent for this Government to recognize at the present time the independence of the so-called Cuban Republic.”82

The leaders of the Cuban revolution met on November 10, 1898, in order to establish a new government. The United States recognized neither the commission nor the government, stating that the war with Spain was a result of the sinking of the USS Maine, not to liberate Cuba.83

• The Cubans were excluded from peace talks with Spain.

• The United States simply became the new ruler and colonizer, as the Platt Amendment confirmed four years later.

• When the last Spanish troops departed Cuba, it was the American flag that was hanging in Havana.84

Within six hours, Commodore George Dewey’s squadron sunk the entire Spanish fleet in Manila Bay, the Philippines.

Unlike the Cubans, the Filipinos did not accept American occupation, fighting a bloody revolutionary war until July of 1902. United States interests were obvious. In addition to being a new market for American goods and investment dollars, the Philippines happens to be just seven hundred miles from China. Besides financial gain, the Philippines would provide the use of military bases in the Pacific, within easy range of the Asian mainland. This would be the initial wedge into Asia, for the expansion of American businesses and banks. In late 1902, just after the fall of the Filipino revolutionaries, the National City Bank opened its first branch in Manila. Possession of the Philippines by the United States changed the entire power base in the Far East.

Filipino casualties on the first day of Philippine-American War. Original caption is “Insurgent dead just as they fell in the trench near Santa Ana, February 5th. The trench was circular, and the picture shows but a small portion.” Unknown US Army soldier or employee, 1899.

United States Assistant Secretary of the Treasury Frank A. Vanderlip—soon-to-be president of the National City Bank and one of the architects of the Federal Reserve—said:

It is as a base for commercial operations that the islands seem to possess the greatest importance. They occupy a favored location not with reference to one part of any particular country of the Orient, but to all parts. Together with the islands of the Japanese Empire, since the acquirement of Formosa, the Philippines are the pickets of the Pacific, standing guard at the entrances to trade with the millions of China and Korea, French Indo-China, the Malay Peninsula and the Islands of Indonesia to the south.85

Captain Alfred T. Mahan, head of the Naval War College and a leading expansionist, reasoned that America’s survival depended upon a strong navy and the acquisition of island possessions to be used as naval bases in the Pacific. The time was ripe, Mahan preached, for Americans to turn their “eyes outward, instead of inward only, to seek the welfare of the country.”86 Out of Mahan’s lectures grew two major works on the historical significance of sea power. In these volumes he argues that naval power was the key to success in international politics. The country that controlled the seas would control modern warfare. Theodore Roosevelt and others who believed that a big navy and overseas expansion were vital to the nation’s welfare were greatly influenced by his writings. Controlling the Pacific would necessitate the need for the creation of a true two-ocean navy, which would also necessitate the development of a canal across Central America.

This was a well-oiled machinery from top to bottom, taking America into a position of world dominance, especially with regard to Latin America and Asia. For several years, Pulitzer and Hearst bandied back and forth, exciting the citizenry into a crazed frenzy against the imagined Spanish tyrants. Then, right before the Cubans were about to claim victory and independence from foreign control (as Fidel Castro succeeded in doing a half century later), 260 sailors most likely became casualties of war so that the legislators and the president could begin the assimilation of sovereign territories, with the military pulling off an invasion on two fronts with a precision that was most likely the envy of every other navy in the world. If the USS Maine had not exploded, the wealth and power of the United States would not have increased exponentially throughout Asia and Central and South America in the years prior to World War I.

A late twentieth-century investigation concluded that the probable cause of the loss of the Maine was a boiler problem. Whether or not that “problem” was sabotage will almost certainly never be known. What we do know, however, is that “Remember the Maine !” was the American slogan used for the acquisition of Guam, Hawaii, the Philippines, Puerto Rico, the control over the Cuban people and economy for a half century, and the permanent occupation of Guantanamo Bay for military purposes, all in the name of freeing the Cuban citizenry from the Spanish monsters. And in the process, almost three hundred thousand died, including over two hundred thousand Filipino citizens. The Spanish-American War and its aftermath planted the seed for the ravages of the next century.

Shows territories and possessions of the United States after the Spanish American War, including Alaska, Cuba, Hawaii, Marianas, Philippines, Puerto Rico, and Samoa in addition to the continental United States. Printed in the book War in the Philippines by Marshall Everet, 1899.

Political satire showing Manifest Destiny bringing the children of Uncle Sam’s new American states and country acquisitions into America’s fold, assimilating their population. Keppler, Udo J., 1898.