The Day of Infamy—or Was It the Day of Foreknowledge?

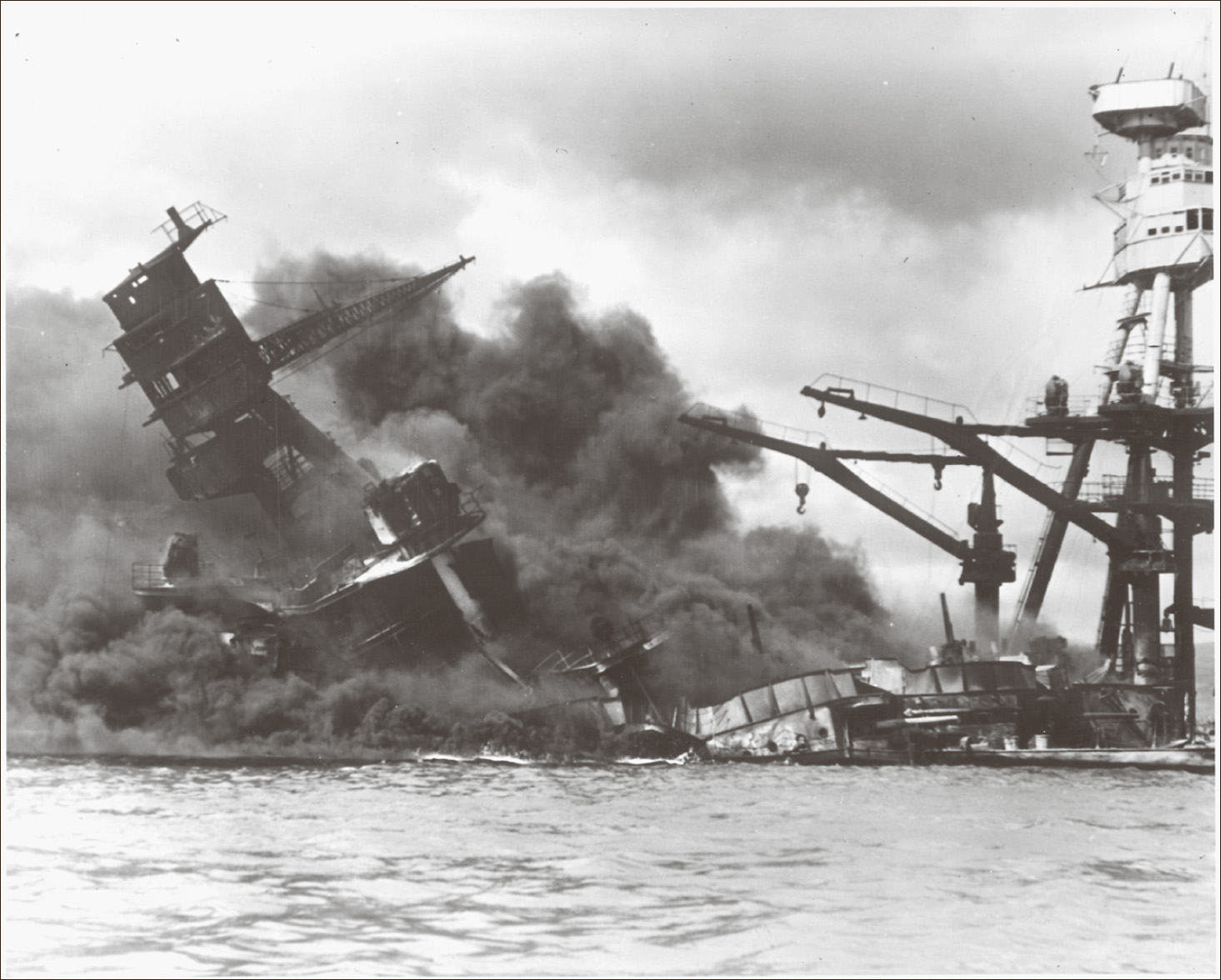

Naval photograph documenting the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Hawaii which initiated US participation in World War II. US Navy caption: The battleship USS Arizona sinking after being hit by Japanese air attack on December 7, 1941. US National Archives, December 7, 1941.

President Roosevelt’s famous “Day of Infamy” speech following the Japanese attack at Pearl Harbor was characteristic of so many before and after—including McKinley’s “Remember the Maine!” and Bush’s “Axis of Evil” and “War on Terrorism”—all featuring slogans to rally the American people into war. Soon after World War II ended, Congress and the military conducted several investigations into the Pearl Harbor debacle. How could such a tragedy have occurred? Toward that end, the government declassified a good deal of material in order to conduct its investigation. Not unlike the Warren Commission on JFK’s assassination, nothing indicating any wrongdoing was reported by the nine individual commissions.

But George Morgenstern, using the same declassified information, revealed in his 1947 book Pearl Harbor: The Story of the Secret War that Pearl Harbor not only could have been avoided but that FDR and his administration caused it to happen. A graduate of the University of Chicago, a Marine Corps captain during the war, and an editor at the Chicago Tribune, Morgenstern claimed that the United States conducted a “secret war” that was waged in the months and even years leading up to Pearl Harbor:101 “Four years later it would become known that the Jap secret code had been cracked many months before Pearl Harbor, and that the men in Washington who read the code intercepts had almost as good a knowledge of Japanese plans and intentions as if they had been occupying seats in the war councils of Tokyo.”102

The Roosevelt Administration knew full well that American servicemen at Pearl Harbor were in harm’s way; that attack was imminent—yet neither the island nor the base was ever placed on full military alert.

On January 27, 1941 (ten months prior to Pearl Harbor), United States Ambassador to Japan Joseph C. Grew wrote a memo to his superiors: “A member of the embassy was told by my Peruvian colleague that from many quarters, including a Japanese one, he had heard that a surprise mass attack on Pearl Harbor was planned by the Japanese military forces, in case of “trouble” between Japan and the United States; that the attack would involve the use of all the Japanese military forces. My colleague said that he was prompted to pass this on because it had come to him from many sources, although the plan seemed fantastic.”103 Grew was no clerk sitting at a desk in an FBI office. This was the representative selected by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt to represent the United States of America in one of the world’s powerhouse nations at that time.

Roosevelt purposely backed Japan into a corner with economic sanctions, whereby they were forced to go to war:

• On October 16, 1940, the US restricted all sales of scrap iron and steel to all countries except Great Britain and countries in the Western Hemisphere, effectively cutting off Japan’s supplies of those crucial metals.

• On July 26, 1941 (just a little more than four months prior to the Pearl Harbor attack), in response to the Japanese occupation of French Indo-China, the US froze all Japanese assets in the United States, effectively ending all trade between the two countries.

• Just one week later, the US cut off all oil sales to Japan, and Britain and the Dutch quickly followed suit. Japan now had access to only approximately 10 percent of its oil requirements.

Japan was in an untenable position with only one way to turn—to war, and the murder of over 2,300 US servicemen and women.

According to noted historian Charles Beard in his President Roosevelt and the Coming of War, on February 11, 1941 (nine months prior to Pearl Harbor), FDR proposed sacrificing six cruisers and two aircraft carriers in Manila, Philippines, in order to get America into war with Japan.104 [S. H. Note: This is reminiscent of Operation Northwoods, which will be discussed later.] The commander of the Pearl Harbor destroyers, Admiral Robert Theobald, argues in The Final Secret of Pearl Harbor that Roosevelt deliberately withheld information from the commanders at Pearl Harbor, never alerting them to the imminent attack.

The recurrent fact of the true Pearl Harbor story has been the repeated withholding of information from Admiral Kimmel and General Short. If the War and Navy Departments had been free to follow the dictates of the Art of War, the following is the minimum of information and orders those officers would have received:

. . . On November 28, the Chief of Naval Operations should have ordered Admiral Kimmel to recall the Enterprise from the Wake operation, and a few days later should have directed the cancellation of the contemplated sending of the Lexington to Midway.

As has been repeatedly said, not one word of this information and none of the foregoing orders were sent to Hawaii.

Everything that happened in Washington on Saturday and Sunday, December 6 and 7, supports the belief that President Roosevelt had directed that no message be sent to the Hawaiian Commanders before noon on Sunday, Washington time.105

Exactly as Lord Curzon had predicted immediately after World War I, the world again went to war. And once again, the American people were almost totally united in their staunch desire to remain neutral. And, again, the United States government made sure that their soldiers would follow the flag into battle with the full support of its populace.

Pearl Harbor became the second time the United States government used mass trauma to incite the public through terror. (The third if you count the sinking of the Lusitania in 1915.) It was the only way FDR could renege on his 1940 campaign pledge not to involve Americans in the European war. By December 8, when Roosevelt asked Congress to declare war on Japan, the public’s isolationist philosophy had been replaced by fear and hatred of the Japanese. President Roosevelt and the United States government methodically and meticulously prepared the American people for war.